Abstract

This multi-method, longitudinal study considered the interplay among depressive symptoms, aversive interpersonal behavior, and interpersonal rejection in early and middle adolescents’ friendships. In particular, the study examined a newly identified interpersonal process, conversational self-focus (i.e., the tendency to redirect conversations about problems to focus on the self). Traditional interpersonal theories of depression suggest that individuals with depressive symptoms engage in aversive behaviors (such as conversational self-focus) and are rejected by others. However, in the current study, not all adolescents with depressive symptoms engaged in conversational self-focus and were rejected by friends. Instead, conversational self-focus moderated prospective relations of depressive symptoms and later friendship problems such that only adolescents with depressive symptoms who engaged in conversational self-focus were rejected by friends. These findings are consistent with current conceptualizations of the development of psychopathology that highlight heterogeneity among youth who share similar symptoms and the possibility of multifinality of outcomes.

Keywords: depression, adolescence, friendship, conversational self-focus

Early to middle adolescence is a developmental period in which youth navigate increased risk for depression as well as the complexities of forming and maintaining close friendships (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006; Sullivan, 1953; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). Yet the relation between adolescents’ emotional well-being and their adjustment in friendships during this period is not well understood. Specifically, it is largely unknown how youths’ depressive symptoms and their interpersonal behavior function together to influence their friendships.

To date, relatively few studies have considered the interrelationships among youths’ depressive symptoms, interpersonal behavior, and adjustment in close friendships (e.g., Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005). Those that have are guided by interpersonal theories of depression, with a focus on Coyne’s (1976a) interpersonal theory of depression. Coyne proposed that depressed individuals sabotage their relationships by engaging in aversive behaviors that lead to rejection by close others.

Surprisingly, however, few such behaviors have been identified. The two aversive behaviors that have been systematically studied are excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking. Excessive reassurance seeking refers to repeatedly requesting assurances that one is truly cared for and worthy, and negative feedback seeking refers to soliciting negative feedback from others that confirms negative ideas about the self (Timmons & Joiner, 2008). These behaviors are linked with depressive symptoms and with interpersonal problems among adults (e.g., Joiner, 1995; Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992, 1993; Joiner & Metalsky, 1995; Starr & Davila, 2008; Swann, Wenzlaff, Krull, & Pelham, 1992; Swann Wenzlaff & Tafarodi, 1992). A smaller number of studies also indicate that adolescents’ excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking are linked with depressive symptoms and with relationship difficulties (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Joiner, Katz, & Lew, 1997; Prinstein et al., 2005).

Clearly, work on excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking indicate that considering aversive interpersonal behaviors is important for better understanding the relationship difficulties of individuals with depressive symptoms. At the same time, it is highly unlikely that individuals with depressive symptoms limit their aversive behavior only to excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking. Identifying and studying additional aversive behaviors that may undermine the relationships of individuals with depressive symptoms is critical.

Conversational Self-Focus

Coyne’s theoretical work (1976b) suggests a potentially important depression-linked aversive behavior that has been overlooked. Coyne proposed that “...it is the nonreciprocal, high disclosure of intimate problems by depressed persons” that may adversely affect close relationships (p. 192). These speculations by Coyne prompted the development of the construct referred to as conversational self-focus (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009). In the context of problem talk, conversational self-focus is the tendency to re-direct conversations about problems to focus on one’s own trials and tribulations.

Extrapolating from Coyne’s theoretical work, conversational self-focus would be expected to be: a) especially common among individuals with depressive symptoms and b) related to poor relationship outcomes. In terms of associations with depression, individuals with depressive symptoms exhibit high levels of self-focused attention (i.e., Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987) and ruminative coping (e.g., Hankin, 2008), which may make it difficult for them to disengage from thoughts about the self. This perseverant cognitive self-focus may manifest behaviorally during conversations about problems with friends. Specifically, individuals with depressive symptoms may have difficulty disengaging from thoughts about the self in order to participate in a reciprocal exchange. Self-focused attention also may interfere with their ability to respond to social cues, such as a friend wanting to talk. As such, they may dominate conversations.

In terms of relationship adjustment, conversational self-focus also would be expected to be related to poorer relationship outcomes. Unfortunately, self-focusing during conversations about problems may be perceived as aversive by relationship partners. In this type of one-sided disclosure, conversation partners likely fail to reap the benefits of normative disclosure (e.g., Burhmester & Prager, 1995) if the focus of conversations is repeatedly directed away from them. Partners may feel as if they cannot rely on self-focused individuals for support and may distance themselves from the relationships. Possible negative outcomes for self-focused individuals may include relationship partners’ perceptions that the relationships are of low quality and relationship partners’ behavioral withdrawal from contact with the self-focused individuals.

Despite some conceptual overlap of conversational self-focus, cognitive self-focused attention/rumination, normative self-disclosure, and other depression-linked interpersonal behaviors (i.e., excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking), there are important theoretical distinctions among the constructs. Whereas self-focused attention and rumination represent cognitive processes, conversational self-focus can be thought of as a social-behavioral manifestation of this cognitive self-focus. In addition, conversational self-focus is distinct from normative self-disclosure, which typically is reciprocal, in that it involves a focus on one conversation partner to the exclusion of the other. In terms of the other depression-related interpersonal behaviors, conversational self-focus is similar to excessive reassurance-seeking and negative feedback seeking in that all three behaviors are thought to be aversive behaviors characteristic of individuals with depressive symptoms. However, only conversational self-focus is unrelated to feedback from the conversation partner. That is, whereas individuals who engage in excessive reassurance seeking or negative feedback seeking aim to elicit particular responses from relationship partners (Timmons & Joiner, 2008), individuals who engage in conversational self-focus are likely to persist in talking about the self regardless of the response from the partner.

To date, only one study has considered the construct of conversational self-focus (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009). In this study, conversational self-focus was reliably assessed using observations of adolescent friends’ conversations about problems. Consistent with hypotheses, adolescents’ observed self-focus was concurrently associated with elevated depressive symptoms and lower levels of friend-reported positive friendship quality. Self-focus was unrelated, however, to normative self-disclosure processes and only moderately related to cognitive rumination. Most importantly, conversational self-focus, self-disclosure, and rumination were related to depressive symptoms and friendship problems in patterns that were conceptually meaningful and not redundant with one another.

Although these initial findings suggest that considering conversational self-focus in adolescent friendships may be important, the study was limited in its ability to further our understanding of conversational self-focus by its small sample (N = 60 youth in 30 dyads) and its focus on concurrent (rather than prospective) relationships. The focus on concurrent associations is a particularly critical limitation because the study was not able to examine the proposed temporal ordering of the relations (i.e., that depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus contribute to increased friendship problems over time).

The Current Study

The current prospective, multi-method study aimed to extend our limited understanding of conversational self-focus in adolescents’ friendships. Adolescence is an important developmental period in which to study conversational self-focus in the contexts of friendships because friends are central sources of social support at this age (Rubin et al., 2006). Moreover, by adolescence, friends typically expect one another to demonstrate perspective taking and reciprocity in the relationship (Parker, Rubin, Erath, Wojslawowicz, & Buskirk, 2006). Therefore, adolescent friends likely expect one another to talk about problems in ways that are reciprocal and mutually encouraging (Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006). As such, friends who dominate conversations through voicing their own worries and concerns likely violate adolescents’ expectations for friendships.

Specifically, the current study considered two alternative hypotheses regarding how depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus might impact adolescents’ close friendships over time. The first is guided by Coyne’s original conceptualization (1976a), which suggests that depressed individuals engage in aversive interpersonal behaviors, which lead to interpersonal rejection. The present study examined whether adolescents with depressive symptoms are especially likely to experience increased friendship problems over time, and whether this effect is mediated by the tendency to engage in self-focus when talking to friends about problems.

Notably, though, there are assumptions inherent in Coyne’s early model that depart from current conceptualizations of the development of psychopathology. Coyne’s model implies considerable homogeneity in regards to depressed individuals in that the model proposes that depressed individuals as a group engage in aversive behaviors. The model also implies equifinality of relationship outcomes for depressed individuals given that these ubiquitous aversive behaviors are expected to disrupt their interpersonal relationships.

However, it may be that not all individuals with depressive symptoms behave aversively. Variations in individual characteristics (e.g., social skills) may render some individuals with depressive symptoms more likely than others to adopt self-focused conversational styles. If this is the case, then it is plausible that only adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms who engage in aversive interpersonal behaviors, such as conversational self-focus, experience increased difficulties in their friendships over time. In other words, conversational self-focus may moderate the impact of depressive symptoms on friendship problems over time such that depressive symptoms predict increases in friendship problems only for adolescents who engage in conversational self-focus and not for adolescents who refrain from self-focusing. Importantly, this alternative hypothesis is consistent with contemporary views of developmental psychopathology, which highlight heterogeneity within groups of individuals who share some symptoms and the possibility of multifinality of outcomes.

As an additional extension of the current study, a new measure was developed to assess the friendship difficulties of adolescents who engage in conversational self-focus. In the initial study of conversational self-focus (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009), and in studies assessing associations of excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking with friendship problems (Borelli & Prinstein, 2006; Joiner et al., 1997; Prinstein et al., 2005), adjustment in friendships was assessed using traditional measures of friendship quality (e.g., reports of companionship and recreation, validation and caring, etc.). Indeed, in the current study, friends of self-focused youth are expected to perceive the friendships as relatively low quality. However, assessing friendship quality fails to capture the problematic relationship outcomes proposed by Coyne (1976a, b). That is, Coyne proposed that relationship partners of depressed individuals will become less willing to socially engage with depressed individuals and will withdraw from them over time. Following Coyne’s conceptualization, a new friendship rejection measure was developed for the current study to assess friends’ intentional withdrawal from the relationship.

Finally, the roles of gender and age also are considered. Consistent with past research, in the current study, girls and middle adolescents were expected to report greater depressive symptoms than boys and early adolescents (e.g., Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). Also consistent with past studies (e.g., Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994), girls and middle adolescents were expected to have friends who report more positive relationship quality as compared to the friends of boys and early adolescents. The current research also will consider gender and age differences in conversational self-focus, although the only previous study of conversational self-focus (Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009) did not provide strong evidence for gender differences and did not test developmental differences. Gender and age are considered as moderators as well. The associations of depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus with later friendship adjustment may be especially strong for girls and middle adolescents. Girls may react more negatively to self-focus than boys given girls’ stronger relationship orientation and heightened sensitivity to perceived friendship transgressions (MacEvoy & Asher, 2012; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Middle adolescents also may report more friendship problems as a result of friends’ conversational self-focus than early adolescents because mastering reciprocal self-disclosure is an important developmental task of adolescence (Parker et al., 2006).

Method

Participants

Data were collected across three consecutive summers from three cohorts of adolescents who had completed the seventh or tenth grades (Cohort 1 = 160 adolescents in 80 dyads, Cohort 2 = 234 adolescents in 117 dyads, Cohort 3 = 248 adolescents in 124 dyads). Contact information for potential participants was obtained from grade rosters of a public school district in a Midwestern university town. Information describing the study was mailed to 1,771 families, of which 937 were reachable by phone (248 had disconnected telephone numbers and 586 did not respond to phone calls and/or voice messages). Of the 937, 616 did not participate (254 agreed to participate but did not follow through with an appointment and 362 declined), and 321 visited the lab. Each of the 321 participants chose a non-relative, same-age, same-sex friend to accompany them to the lab. This resulted in a sample of 642 adolescents in 321 dyads. Although during recruitment, one adolescent was considered the target adolescent (i.e., the adolescent whose family was contacted and who chose a friend with whom to participate), both adolescents in each friend dyad completed all of the same measures and contributed the same data to the analyses (and both adolescents’ data could be used in analyses due to the analytic approach, which accounted for non-independence between friends’ data). Therefore, we do not refer to one participant in the dyad as the target participant and the other participant as the friend (all participants are simply referred to as adolescents nested within friend dyads).

When adolescents came to the lab (N = 642; in 321 dyads), they each reported on whether the friend with whom they were participating was a best friend (76%), a good friend (23%), or just a friend (1%). One dyad was not included in analyses because one youth in the dyad indicated that they were not friends and the other youth skipped the friendship status item.

The final sample included 640 adolescents in 320 friendship dyads (seventh graders: 162 female, 160 male, M age = 13.02; tenth graders: 168 female, 150 male, M age = 16.04). Participants were 62% European American, 29.8% African American, 6% Multiracial, 1.5% Asian American, and less than 1% each American Indian/Alaskan Native and Pacific Islander/Hawaiian Native. With regard to ethnic identity, 3.6% of the sample was Latino/a.

Of the 640 adolescents who participated at Time 1, 166 did not participate at Time 2. The 474 adolescents who participated at both Times 1 and 2 were compared to the 166 adolescents who did not participate at Time 2. The two groups did not differ on any Time 1 study variable (depressive symptoms, conversational self-focus, positive friendship quality, or friendship rejection). Moreover, Little’s MCAR test indicated that missing data were missing completely at random, χ2 (25823) = 25665.30, p = .76. Therefore, data imputation was considered preferable to other techniques for handling missing data (e.g., listwise deletion, pairwise deletion; see Allison, 2002; Widaman, 2006). Missing data were imputed using an expectation-maximization procedure, and the full sample of 640 adolescents (in 320 friend dyads) was used in all analyses.

Procedure

The friend dyads visited the lab at Time 1. Parents/guardians provided written consent, and adolescents provided written assent. The friends then completed questionnaires in separate rooms. One questionnaire asked each adolescent in the dyad to identify a problem that she or he was currently experiencing and would be willing to discuss with the friend during a later observational task. Friends then were reunited in an observation room equipped with a table, two chairs, and wall-mounted video recording equipment. The first task, planning a party, was a warm-up task not used in the current study. The second task involved each adolescent discussing the problem that he or she generated during the questionnaire assessment. Participants were told that they should discuss both friends’ problems but were not given a specific amount of time to talk about each person’s problem to avoid constraining the display of interpersonal processes of interest (e.g., conversational self-focus). They were told that they had 16 minutes to discuss both friends’ problems. Participants also were told that they could talk about something else and/or play with a puzzle that was on the table if they finished discussing the problems.

Approximately nine months after their initial lab visit, participants were contacted for a follow-up questionnaire assessment. Adolescents either visited the lab or were mailed a packet of questionnaires and a self-addressed, stamped envelope for return mailing.

Observational Coding

The observations from the problem talk task were coded for observed conversational self-focus. First, each recorded interaction was transcribed verbatim and additional details such as verbal inflection, interruptions, and relevant non-verbal behaviors were noted. Coders first read each transcript and then watched the recorded interaction with transcript in hand so that any unclear language could be clarified.

A previously developed and validated coding system (see Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2009) was used to assess the degree to which each adolescent engaged in conversational self-focus. A macrocoding approach allowed coders to simultaneously take into account multiple factors, including the conversational flow and the context of specific statements. Specifically, each adolescent was assigned a score for conversational self-focus on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Very little) to 5 (Very frequent) that assessed the degree to which they made self-statements in response to friends’ statements, changed the subject, and/or dominated the focus of conversations. Participants receiving a rating of 1 or 2 generally refrained from exhibiting any self-focused behavior and maintained a reciprocal give-and-take throughout the conversation. Adolescents receiving a 3 exhibited a moderate level of self-focus. For example, they made self-statements in response to friends’ problem statements (e.g., offered distracting examples of when they experienced similar situations) but did not dominate the entire conversation. Participants receiving a 4 or 5 repeatedly made self-statements in response to friends’ problem statements, changed the subject, and dominated conversations as a result. Highly self-focused adolescents might respond to a friends’ problem statement (e.g., “My boyfriend sucks!”) with a problem statement that is clearly focused on themselves (e.g., “Let me tell you what MY boyfriend did today.”). Two trained raters coded 25% of interactions from each cohort to ensure continued reliability. Inter-rater reliability across cohorts was high (ICCs = .89, .89, .93). The distribution of adolescents who received each of the scores on the 5-point Likert scale was: 1, n = 358; 2, n = 131; 3, n = 49; 4, n = 13; 5, n = 1. Given that only one youth was assigned a score of 5, the decision was made to assign that youth the score of 4, which, in effect, converted the 5-point scale to a 4-point scale.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

At Time 1, adolescents rated each of the 20 items of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) to assess how often within the last week they experienced various affective, somatic, interpersonal, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms of depression. This measure has been used to assess depressive symptoms in both normative and clinical adolescent samples (Prinstein, Boergers, & Spirito, 2001; Roberts, Andrews, Lewinsohn, & Hops, 1990). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from Rarely or none of the time, less than 1 day to Most or all of the time, 5 to 7 days. Each participant received a score that was the sum of the 20 items (Time 1 α = .87).

Friendship outcomes

In terms of friendship outcomes, positive friendship quality and friendship rejection both were assessed. Adolescents completed 15 items from the revised version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Rose, 2002, revision of Parker & Asher, 1993) at Time 1 and Time 2. Three items each assessed: companionship and recreation, conflict resolution, help and guidance, intimate exchange, and validation and caring. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Not at all true to Really true. Due to conceptual overlap between the companionship and recreation items and the behavioral withdrawal items in the rejection measure (see description of measure in the next paragraph), the three companionship and recreation items were not used. In addition, due to conceptual overlap between the intimate exchange (i.e., self-disclosure) items and the construct of conversational self-focus, the three intimate exchange also were not used. Therefore, each adolescent received a score that was the mean of the remaining nine items (i.e., the conflict resolution, help and guidance, and validation items) completed by their friend at Time 1 and Time 2.

Adolescents also responded to a new measure of friendship rejection that was developed for the current study. A new measure was developed because there was no available measure of friendship rejection (i.e., operationalized as behavioral withdrawal from the friend). Items were developed based on Coyne’s descriptions of behavioral rejection by close others (1976b). In developing these items, contemporary issues related to interactions between friends at this developmental stage were taken into account (e.g., the inclusion of items related to electronic communication). Items were subjected to expert review by a senior peer relations scholar and were revised accordingly. Ten items were retained for use in the current study.

Five items assessed the degree to which the friend avoided the adolescent (e.g., “How often do you avoid talking with [ADOLESCENT’S NAME] over text messages and e-mail?”). Five additional (reverse-scored) items assessed the degree to which the friend sought contact with the adolescent (e.g., “How often to do you try to spend time with [ADOLESCENT’S NAME] after school and on weekends?”). Friends rated the degree to which they engaged in each of these behaviors on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Never to All the time. Adolescents completed the measure at Time 1 and Time 2 and were given a score for friendship rejection that was the mean of the 10 items reported by their friend.

Analyses tested whether the new friendship rejection items were distinct from the friendship quality items. At each time point, a one-factor measurement model in which all 19 friendship items loaded on a single factor was compared with a two-factor model in which the 9 friendship quality items and the 10 friendship rejection items loaded on separate factors. The results indicated that the two-factor model fit the data significantly better than the one-factor model at both Time 1, χ2 difference (14) = 25.60, p = .03, and Time 2, χ2 difference (1) = 544.04, p < .0001. Therefore, separate scores were computed for friend-reported positive friendship quality (Time 1 α = .88, Time 2 α = .94) and friend-reported friendship rejection (Time 1 α = .73, Time 2 α = .84).

Data Analysis Plan

Because participants were nested within friend dyads, data from each participant could not be considered independent sources of information (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). Indeed, significant interdependence between friends was observed for all study variables (Time 1 depressive symptoms ICC = .12, p <.01, Time 1 positive friendship quality ICC = .44, p < .0001, Time 2 positive friendship quality ICC = .45, p <.0001, Time 1 friendship rejection ICC = .31, p <.0001, Time 2 friendship rejection ICC = .39, p < .0001, Time 1 conversational self-focus ICC = .10, p < .01). Therefore, statistical techniques that account for dependency in dyadic data were used. Multilevel models with adolescents nested in friend dyads were tested using Proc Mixed in SAS. More specifically, to test the primary hypotheses, the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny, 1996) was adopted. With this approach, data from all 640 participants (nested in 320 friend dyads) could be used to test actor effects (e.g., the relation between an adolescent’s depressive symptoms score and his/her own score for conversational self-focus) and partner effects (e.g., the relation between an adolescent’s conversational self-focus score and his/her friend’s report of friendship quality or friendship rejection).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analyses

Prior to conducting analyses, the distributions of the study variables were examined. Skew and kurtosis values for all study variables fell within acceptable limits (all skew values fell within +/− 1.6, kurtosis values fell within +/− 2.30, with 0 representing a normal distribution). Means and standard deviations for the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 CES-D (self-report) | 11.49 | 8.20 | -- | ||||

| 2. T1 Positive FQ (friend-report) | 3.03 | 0.72 | 0.02 | -- | |||

| 3. T2 Positive FQ (friend-report) | 2.60 | 0.87 | −0.06 | 0.67**** | -- | ||

| 4. T1 Friendship Rejection (friend-report) | 2.13 | 0.54 | 0.00 | −0.49**** | −0.35**** | -- | |

| 5. T2 Friendship Rejection (friend-report) | 2.50 | 0.68 | 0.11** | −0.22**** | −0.60**** | 0.34**** | -- |

| 6. T1 Conversational Self-Focus (obs.) | 1.47 | 0.75 | 0.11** | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.11** |

Notes.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

CES-D. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. FQ=friendship quality.

Particular attention was paid to the descriptive information for depressive symptoms in order to evaluate the level of symptoms in the current sample. The mean level of depressive symptoms observed in the current study was similar to that presented in previous research with community samples (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001). Scores ranged from 0–48 (out of a possible 60). The prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptomatology in the current sample was 23% (n = 147), as defined by the standard criterion sum score of 16 or greater (Radloff, 1977). Some researchers have advocated using a slightly higher cutoff of 19 for adolescents (given that adolescents tend to score higher than adults; Roberts et al., 1990), which would result in 17% (n = 108) of the sample being classified as having clinically significant depressive symptomatology.

Bivariate correlations among study variables also are presented in Table 1. The relation between depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus was positive and significant but modest in magnitude. In addition, a small but significant positive correlation was observed between Time 1 depressive symptoms and friend-reported friendship rejection at Time 2. The relations between Time 1 depressive symptoms and the other friendship variables (Time 1 quality and rejection, Time 2 quality) were not significant. The relation between Time 1 conversational self-focus and Time 2 friend-reported friendship rejection was positive and significant but not large in magnitude. The relations of Time 1 conversational self-focus and the other friendship variables (Time 1 quality and rejection, Time 2 quality) were not significant.

Mean-level Gender and Grade Differences

Two-level multilevel models (with adolescents nested in friend dyads) were tested to examine mean-level gender and grade differences. Six separate models were tested (one for each dependent variable: Time 1 depression, Time 1 conversational self-focus, Time 1 friendship quality, Time 1 friendship rejection, Time 2 friendship quality, Time 2 friendship rejection). In each model, the dependent variable was predicted from gender, grade, and their interaction. Results of these analyses are summarized in Table 2. The effect of gender was significant for Time 1 depression, with girls reporting higher levels of depression than boys. For conversational self-focus, the effect of gender was significant, with girls observed to engage in greater self-focus than boys. Gender also significantly predicted both Time 1 and Time 2 friend-reported positive friendship quality such that friends of girls reported higher positive quality than friends of boys. Finally, the effect of gender was significant for Time 1 friendship rejection, such that friends of boys reported higher levels of rejection than friends of girls. The gender effect for Time 2 friendship rejection was not significant. None of the grade effects or gender by grade interactions were significant. Given the significant mean-level gender differences, gender was controlled in all following analyses that tested the primary hypotheses of the study. Although the grade differences were not significant, grade also was controlled in all following analyses to be certain that no significant effects could be due to grade-related variation in the data.

Table 2.

Mean-Level Gender Differences in Study Variables

| Girls M (SD) |

Boys M (SD) |

Gender SPE |

Grade SPE |

Interaction SPE |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D (Time 1) | 13.11 (8.90) | 9.77 (7.00) | −0.20**** | 0.06 | −0.06 |

| Positive FQ (Time 1) | 3.29 (0.55) | 2.76 (0.77) | −0.37**** | −0.03 | −0.07 |

| Positive FQ (Time 2) | 2.83 (0.86) | 2.38 (0.82) | −0.26**** | 0.00 | −0.02 |

| Friendship Rejection (Time 1) | 1.96 (0.51) | 2.30 (0.51) | 0.32**** | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Friendship Rejection (Time 2) | 2.47 (0.78) | 2.53 (0.54) | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.06 |

| Conversational Self-Focus (Time 1) | 1.57 (0.82) | 1.36 (0.65) | −0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Notes.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

SPE = standardized parameter estimate. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. FQ = friendship quality.

The Relation Between Depressive Symptoms and Later Friendship Problems: Conversational Self-Focus as a Potential Mediator

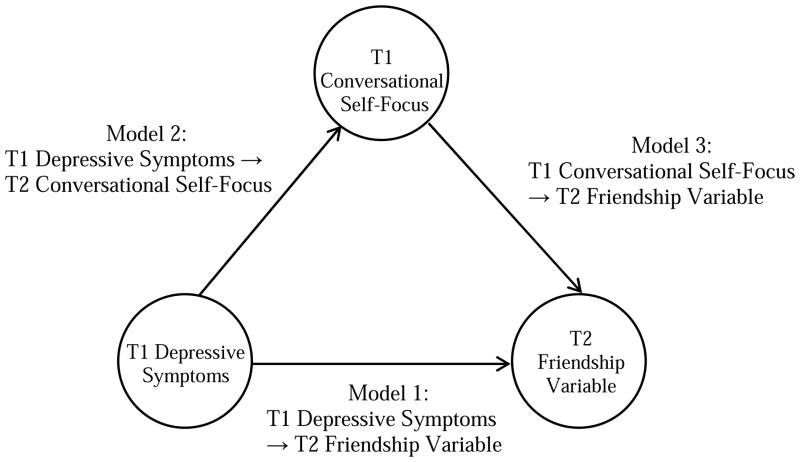

In this section, analyses tested whether conversational self-focus mediated the relation between depressive symptoms and later friendship problems (low friend-reported positive quality and friend-reported rejection). A conceptual depiction of the mediation model tested in these analyses is presented as Figure 1. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of Time 1 conversational self-focus as a mediator of the relation between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 2 friendship problems.

Table 3.

Conversational Self-Focus as a Mediator of the Relation Between Time 1 Depressive Symptoms and Time 2 Friend-Reported Friendship Problems

| Time 2 Positive Friendship Quality | Time 2 Friendship Rejection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPE | t | SPE | t | |

| Model 1: T1 Depressive Symptoms → T2 Friendship Variable | ||||

| Time 1 Friendship Variable | 0.62 | 19.67**** | 0.37 | 9.86**** |

| Gender | −0.03 | 0.79 | −0.07 | 1.51 |

| Grade | 0.01 | 0.41 | −0.02 | 0.60 |

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms | −0.02 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.81 |

| Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus | Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPE | t | SPE | t | |

| Model 2: T1 Depressive Symptoms → T1 Conversational Self-Focus | ||||

| Time 1 Friendship Variable | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.38 |

| Gender | −0.12 | 2.83** | −0.14 | 3.35*** |

| Grade | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.54 |

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms | 0.08 | 2.06* | 0.08 | 1.96* |

| Time 2 Positive Friendship Quality | Time 2 Friendship Rejection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPE | t | SPE | t | |

| Model 3: T1 Conversational Self-Focus → T2 Friendship Variable | ||||

| Time 1 Friendship Variable | 0.62 | 19.72**** | 0.36 | 9.64**** |

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.97 | −0.06 | 1.21 |

| Grade | 0.02 | 0.45 | −0.03 | 0.65 |

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms | −0.02 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.73 |

| Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus | −0.05 | 1.87† | 0.08 | 2.44* |

Notes.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

SPE = standardized parameter estimate.

Analyses first considered friend-reported positive friendship quality. In order to test for mediation, three multilevel models were tested. The main goal of the first model was to test whether Time 1 depressive symptoms predicted changes in positive friendship quality over time. In this model, Time 2 positive friendship quality was the dependent variable. Predictor variables included Time 1 positive friendship quality, gender, and grade (included as controls) and Time 1 depressive symptoms. Time 1 positive friendship quality was a significant positive predictor of Time 2 positive friendship quality. The effects of gender and grade were non-significant. Adolescents’ Time 1 depressive symptoms did not predict friend-reported friendship quality at Time 2. Because this association was not significant, it could not be mediated by a third variable (i.e., self-focus). However, the remaining two models were tested for descriptive purposes.

The second model tested the relation between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus. Time 1 conversational self-focus was the dependent variable. Predictor variables were Time 1 positive friendship quality, gender, and grade (included as controls) and Time 1 depressive symptoms. The main effect of gender was significant, with girls observed to engage in greater conversational self-focus than boys. The effects of Time 1 positive friendship quality and grade were not significant. Time 1 depressive symptoms did predict Time 1 conversational self-focus, such that adolescents who reported greater depressive symptoms were observed to engage in higher levels of conversational self-focus.

The third model tested the relation between Time 1 conversational self-focus and Time 2 friend-reported positive friendship quality. Time 2 positive friendship quality was the dependent variable. Predictors included Time 1 positive friendship quality, gender, and grade (included as controls), Time 1 depressive symptoms (required as a control when testing meditation models), and Time 1 conversational self-focus. Time 1 positive friendship quality was a significant positive predictor. The effects of gender, grade, and Time 1 depressive symptoms were not significant. The effect of Time 1 conversational self-focus on Time 2 positive friendship quality was marginally significant, such that higher levels of conversational self-focus predicted decreases in friends’ reports of positive friendship quality over time.

Finally, it should be noted that, for each of the three models, interaction effects were initially included in each model. Specifically, all possible interactions between the primary predictor variable of interest (Time 1 depressive symptoms in models 1 and 2, Time 1 conversational self-focus in model 3) with gender and grade were included. However, none of these effects were significant. Therefore, the interaction terms were excluded from the final models and are not included in Table 3.

Analyses next considered friend-reported friendship rejection. Again, three multilevel models were tested. The first model tested whether Time 1 depressive symptoms predicted changes in friendship rejection over time. Time 2 friendship rejection was the dependent variable. Predictor variables were Time 1 friendship rejection, gender, and grade (included as controls) and Time 1 depressive symptoms. The effect of Time 1 friendship rejection was positive and significant. The effects of gender and grade were not significant. Adolescents’ Time 1 depressive symptoms did not predict their friends’ reports of friendship rejection at Time 2. Given that this relation was not significant, it could not be mediated by a third variable. However, the remaining two models were tested for descriptive purposes.

The second model tested the association between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus. Conversational self-focus was the dependent variable. Predictor variables included Time 1 friendship rejection, gender, and grade (as controls) and Time 1 depressive symptoms. The effect of gender was significant. The effects of Time 1 friendship rejection and grade were not significant. Time 1 depressive symptoms did significantly and positively predict conversational self-focus.

The third model tested the association between Time 1 conversational self-focus and Time 2 friendship rejection. Time 2 friendship rejection was the dependent variable. Predictor variables were Time 1 friendship rejection, gender, and grade (included as controls), Time 1 depressive symptoms (required as a control for testing meditation models), and Time 1 conversational self-focus. The effect of Time 1 friendship rejection was significant. The effects of gender, grade, and Time 1 depressive symptoms were not significant. Conversational self-focus did significantly predict increased friend-reported friendship rejection over time.

In each of the three models, all possible interactions between the primary predictor variable of interest (Time 1 depressive symptoms in models 1 and 2, Time 1 conversational self-focus in model 3) with gender and grade were initially included. None of these interaction effects were significant and they were excluded from the final models presented in Table 3.

The Relation Between Depressive Symptoms and Later Friendship Problems: Conversational Self-Focus as a Potential Moderator

Analyses next considered whether conversational self-focus moderated relations between adolescent depressive symptoms and later friendship problems. Separate multilevel models (with adolescents nested within friend dyads) were tested for Time 2 friend-reported positive friendship quality and Time 2 friend-reported friendship rejection as the dependent variable. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effects of Adolescents’ Time 1 Depressive Symptoms and Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus on Time 2 Friend-Reported Friendship Quality and Friendship Rejection

| Time 2 Positive Friendship Quality | ||

|---|---|---|

| SPE | t | |

| Step 1 | ||

| Time 1 Positive Friendship Quality | 0.62 | 19.70**** |

| Gender | −0.02 | 0.66 |

| Grade | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| Step 2 | ||

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms | −0.02 | 0.86 |

| Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus | −0.05 | 1.87† |

| Step 3 | ||

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms X Time 1 Self-Focus | −0.05 | 2.07* |

| Time 2 Friendship Rejection | ||

|---|---|---|

| SPE | t | |

| Step 1 | ||

| Time 1 Friendship Rejection | 0.37 | 9.93**** |

| Gender | −0.08 | 1.66 |

| Grade | −0.02 | 0.56 |

| Step 2 | ||

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms | 0.03 | 0.73 |

| Time 1 Conversational Self-Focus | 0.08 | 2.44* |

| Step 3 | ||

| Time 1 Depressive Symptoms X Time 1 Self-Focus | 0.05 | 1.77† |

Notes.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .0001.

SPE = standardized parameter estimate.

In the first model, Time 2 friend-reported positive friendship quality was the dependent variable. Time 1 positive friendship quality, gender, and grade were entered on Step 1 as controls. Time 1 positive friendship quality significantly predicted greater Time 2 positive friendship quality. The effects of gender and grade were not significant. On Step 2, adolescents’ Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus were entered as simultaneous predictors. Depressive symptoms did not significantly predict Time 2 positive friendship quality. The effect of Time 1 conversational self-focus on Time 2 positive friendship quality was marginally significant. On Step 3, the interaction between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus was entered. The interaction effect was significant. Initially, a fourth step was included in which all possible interactions of Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus with gender and grade were tested. None of the interactions were significant. Therefore, the interaction effects were excluded from the final models and are not included in Table 4.

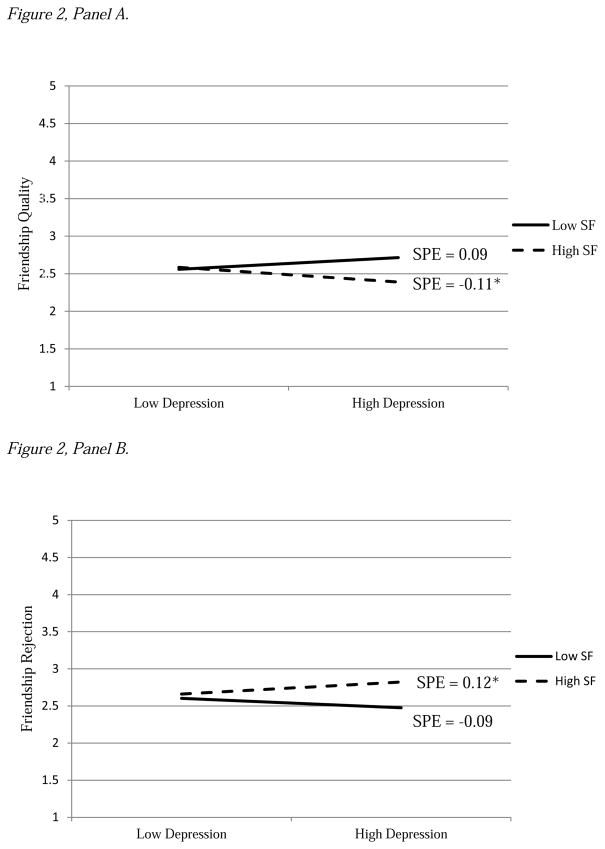

Simple slope analyses (Aiken & West, 1991; Holmbeck, 2000) were conducted to examine the effect of depressive symptoms on positive friendship quality for youth who were observed to engage in high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of conversational self-focus (see Figure 2, Panel A). As expected, adolescents’ Time 1 depressive symptoms significantly predicted friends’ reports of lower positive friendship quality at Time 2 for youth who were observed to engage in high levels of conversational self-focus, SPE = -.23, t = 2.93, p <.01. For adolescents who engaged in low levels of conversational self-focus, Time 1 depressive symptoms were unrelated to Time 2 positive friendship quality, SPE = .07, t = 1.67, p = ns.

Figure 2.

Panel A. Effect of Time 1 depressive symptoms on Time 2 friend-reported positive friendship quality at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of conversational self-focus.

Panel B. Effect of Time 1 depressive symptoms on Time 2 friendship rejection at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of conversational self-focus.

Notes. *p < .05. SPE = standardized parameter estimate.

Analyses next considered friend-reported friendship rejection. In this model, Time 2 friendship rejection was the dependent variable. Time 1 friendship rejection, gender, and grade were entered as controls on a first step. Only the effect of Time 1 rejection was significant. On Step 2, Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus were entered. Time 1 depressive symptoms did not significantly predict Time 2 friendship rejection, but the effect of Time 1 conversational self-focus was significant such that higher levels of self-focus predicted increased friend-reported friendship rejection over time. On Step 3, the interaction between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus was entered. The interaction was marginally significant. All possible interactions of Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 conversational self-focus with gender and grade initially were entered on a fourth step. Because none were significant, the interaction terms were excluded from the final models.

Given that interactions are difficult to detect in studies with non-experimental designs (McClelland & Judd, 1993), the decision was made to probe the marginally significant interaction. Simple slope analyses (see Figure 2, Panel B) indicated that adolescents’ Time 1 depressive symptoms predicted friends’ reports of greater rejection at Time 2 for youth who were observed to engage in high levels (+1 SD) of conversational self-focus, SPE = .24, t = 2.85, p <.01. However, depressive symptoms were unrelated to Time 2 rejection for adolescents who engaged in low levels (−1 SD) of conversational self-focus, SPE = −.04, t = .85, p = ns.

Discussion

The current study provides novel information regarding the interplay among adolescents’ depressive symptoms, interpersonal behaviors, and friendship adjustment by examining a new, depression-linked interpersonal behavior, conversational self-focus. The study provided a specific test of a proposal stemming from Coyne’s interpersonal theory of depression (1976b)—namely, that the aversive behavior of depressed individuals erodes their close relationships. However, the current findings did not support the meditation model based on Coyne’s proposal. Instead, the findings were consistent with more contemporary views of the development of psychopathology, which highlight the possibility of heterogeneity among individuals who share certain symptoms and of multifinality in regards to outcomes.

In order to test Coyne’s proposal that depressed individuals experience relationship problems as a result of their aversive interpersonal behavior (i.e., conversational self-focus in the present research), analyses first needed to indicate that adolescents’ initial depressive symptoms predicted their friends’ later reports of friendship quality and rejection. However, depressive symptoms did not predict deteriorating friendship quality or increased rejection by friends over time. To some extent, these findings were surprising. Certainly, there are strong conceptual reasons to believe that individuals with elevated depressive symptoms may experience increases in relationship problems over time (Coyne, 1976a, b; Gotlib & Hammen, 1992). However, a close review of the literature suggests that the association between depressive symptoms and friendship problems may not be as strong or consistent as would be expected. Although some studies do find associations between depressive symptoms and friendship problems for youth (e.g., Brendgen, Vitaro, Turgeon, & Poulin, 2002; Prinstein et al., 2005; Vernberg, 1990), other studies do not find significant relations (e.g., Hussong, 2000; LaGreca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein, 2007).

When a conceptually meaningful relation, such as the relation between depressive symptoms and adolescents’ friendship adjustment, fails to emerge or is weak or inconsistent across studies, this begs the question of whether the relation may hold true only for some individuals. In the current study, whether the relation between depressive symptoms and later friendship problems was especially strong for youth who engaged in conversational self-focus was examined.

In fact, conversational self-focus did moderate the relation such that depressive symptoms predicted friendship problems only for youth who engaged in conversational self-focus. There are several reasons why adolescents with depressive symptoms who also self-focus may be especially at risk for friendship problems. Adolescents with depressive symptoms who do not engage in conversational self-focus may evoke more sympathy from friends than adolescents with depressive symptoms who are very egocentric in their conversational style. As a result, friends may feel more emotionally connected to and less frustrated with youth with depressive symptoms who do not self-focus and be less likely to reject them. In contrast, adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms who do self-focus may be perceived by friends as especially annoying and abrasive. Friends may be unable to reap the benefits of reciprocal disclosure, grow to perceive the friendship as low quality, and reject the self-focused adolescent.

As a related point, it will be important to examine why some youth with depressive symptoms do not engage in conversational self-focus. Conceptually, depressive symptoms were expected to be associated with conversational self-focus because individuals with depressive symptoms typically have high levels of self-focused attention (Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987) and may have difficulty disengaging from their own problems during conversations with friends. In fact, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with greater conversational self-focus. However, this relation was relatively small. The magnitude of the association indicates that not all adolescents with depressive symptoms engaged in conversational self-focus.

Individual differences in social skills and in social-cognitive skills (e.g., perspective-taking, self-awareness) may to help explain why some adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms self-focus and some do not. Youth with depressive symptoms tend to exhibit deficits in social and social-cognitive skills (e.g., Kovacs & Goldston, 1991). However, some youth with depressive symptoms struggle with these skills more than others. Given that depressive symptoms are associated with self-focused attention, it may be that only youth with relatively effective social and social-cognitive skills are able to recognize that conversational self-focus is inappropriate and to shift the focus of the conversation back to the friend.

The current study also considered gender and grade differences. In terms of gender, as expected, girls reported higher levels of depressive symptoms. Friends of girls also reported greater positive friendship quality and lower friendship rejection compared to the friends of boys. Other findings indicated that girls engaged in greater conversational self-focus than boys. This was somewhat surprising given girls’ greater social perspective taking skills (e.g., Smith & Rose, 2011) and the finding is in need of replication. In addition, none of the primary relations of interest were moderated by gender, indicating that the combination of depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus had a similarly negative effect on girls’ and boys’ friendships. Replication with an even larger sample with greater statistical power will be useful for corroborating the current findings, though, given that higher-order interactions are difficult to detect in non-experimental studies (McClelland & Judd, 1993).

Also, although hypotheses were put forth regarding grade differences, no mean-level grade differences emerged. Associations among variables also did not differ by grade. However, a limitation of the current study is that a relatively narrow age range was considered. Developmental differences might have emerged if a larger age range had been considered. As an example, expectations for reciprocal disclosure may be stronger among adolescents than children, in which case conversational self-focus may be more problematic for the friendships of adolescents than for the friendships of children.

Additional future research that incorporates other aversive behaviors also is needed. For instance, studies could simultaneously examine excessive reassurance seeking, negative feedback seeking, and conversational self-focus to test whether these behaviors have additive effects on relationship adjustment or interactive effects (e.g., such that the presence of each behavior exacerbates the deleterious effects of the others). Future work also could consider whether these behaviors are similarly aversive or whether some of these behaviors are especially problematic. One possibility is that excessive reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking are less aversive than conversational self-focus because they express vulnerability and convey interest in the friend’s perceptions.

Relations among depressive symptoms, conversational self-focus, and friendship adjustment also could be considered in clinical as well as community samples. There may be more homogeneity of interpersonal behavior and greater equifinality of relationship outcomes among severely (i.e., clinically) depressed adolescents than among adolescents with elevated symptoms in community samples. Youth with particularly debilitating depressive symptoms may have the most difficulty refraining from aversive behaviors and, therefore, experience similarly negative friendships outcomes. If this is the case, then Coyne’s model (1976a)—which suggests that depressed individuals as a group engage in aversive behaviors and experience relationship problems—may receive more support from research conducted with clinical samples.

Finally, an additional limitation was that only one type of relationship was considered. Future research could examine the joint impact of depressive symptoms and conversational self-focus on adjustment in different types of relationships, including mixed-sex friendships. Conversational self-focus is conceptualized as being damaging to friendships, at least in part because it violates expectations for reciprocal communication. Given that mixed-sex friendships are relatively uncommon (Bukowski, Sippola, & Hoza, 1999), most youth have less experience with mixed-sex friends than with same-sex friends Youth may be more accepting of violated expectations in mixed-sex friendship interactions than in same-sex friendship interactions because their schemas for mixed-sex friendships are less well-developed. Alternatively, if same-sex friendships, which are more common, are also more valued, then youth may have less tolerance for frustration in mixed-sex friendships, which could lead to greater rejection.

Despite these limitations, the present study did provide a strong test of the relations among adolescents’ depressive symptoms, conversational self-focus, and difficulties in friendship. The study included a relatively large sample and utilized a longitudinal, multi-method, multi-informant approach. Because depressive symptoms were assessed with self-reports, conversational self-focus was assessed with observation, and friendship problems were assessed using friends’ reports, relations could not be inflated by shared method variance.

The current research also has implications for clinical assessment and intervention. While existing clinical approaches generally acknowledge the role of interpersonal functioning in adolescent depression (e.g., Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004), they do not address specific interpersonal behaviors, such as conversational self-focus. It is reasonable to assume that aversive behavior may continue to undermine relationship functioning if not directly addressed. Regarding assessment, clinicians can utilize multiple methods to assess for potential engagement in conversational self-focus. Consistent with an interpersonal process perspective (e.g., Teyber & McClure, 2011), therapists can glean information about an adolescent’s interpersonal style from their interactions with the adolescent through informal, in-session observation. Therapists also may directly inquire about adolescents’ interpersonal behaviors with friends. Information from clinical assessment then could be used as a platform for intervention.

Regarding intervention, addressing conversational self-focus in therapy is consistent with both interpersonal and cognitive-behavioral approaches. In particular, psychoeducation, perspective-taking activities, and role-playing relevant to conversational self-focus could easily supplement Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for depressed adolescents (Mufson et al., 2004), given that a major treatment target involves identifying and practicing effective communication techniques. Similarly, these techniques could serve as an adjunct to individual and/or group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for adolescent depression (Compton et al., 2004), given that the approach involves increasing adaptive interpersonal behavior and pleasant events. Such intervention strategies could enhance adolescents’ self-awareness of their tendencies to engage in depression-related aversive behavior and its negative impact in the friendship context. Moreover, direct intervention may teach adolescents how to disengage from aversive perseverations with friends in favor of engaging in other, more positive behaviors to support friendship health (e.g., offering social support, engaging in pleasant events together, etc.).

In closing, the current study suggests that considering aversive interpersonal behavior may be one way to delineate between adolescents with depressive symptoms who likely are on negative friendship trajectories versus those who may be on more typical and positive trajectories. Understanding how to support and maintain the existing friendships of adolescents with depressive symptoms who engage in aversive behaviors such as conversational self-focus is critical given that friendships typically protect against maladjustment (Waldrip, Malcom, & Jensen-Campbell, 2008). Moving adolescents with depressive symptoms away from non-normative aversive behaviors, such as conversational self-focus, should be a clear goal for clinical intervention. This approach may help adolescents with depressive symptoms curb aversive behaviors, avoid negative relationship trajectories, and preserve friendships that have the potential to bolster their well-being.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH Grant R01 MH 073590 awarded to Amanda J. Rose and NIMH Grant F31 MH 081619 awarded to Rebecca A. Schwartz-Mette. We acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of Ashley Wilson, Rhiannon Smith, Gary Glick, and Aaron Luebbe in regards to data collection.

Contributor Information

Rebecca A. Schwartz-Mette, University of Arkansas

Amanda J. Rose, University of Missouri

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli JL, Prinstein MJ. Reciprocal, longitudinal associations among adolescents’ negative feedback-seeking, depressive symptoms, and peer relations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Turgeon L, Poulin F. Assessing aggressive and depressed children’s social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:609–624. doi: 10.1023/A:1020863730902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Prager K. Patterns and functions of self-disclosure during childhood and adolescence. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 10–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:471–484. doi: 10.1177/0265407594113011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Sippola LK, Hoza B. Same and other: Interdependency between participation in same- and other-sex friendships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:439–459. doi: 10.1023/A:1021664923911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:327–342. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, March JS, Brent DA, Albano AM, Weersing VR, Curry JF. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: An evidence based medicine review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:930–959. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976a;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976b;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Psychological aspects of depression: Toward a cognitive-interpersonal integration. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Greene K, Derlega VJ, Mathews A. Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In: Vangelisti A, Perlman D, editors. Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 409–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Rumination and depression in adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:701–713. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:391–415. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1004_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. The price of soliciting and receiving negative feedback: Self-verification theory as a vulnerability to depression theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:364–372. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Alfano M, Metalsky G. Caught in the crossfire: Depression, self- consistency, self-enhancement, and the response of others. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:113–134. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1993.12.2.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Katz J, Lew A. Self-verification and depression in youth psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:608–618. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Metalsky G. A prospective test of an integrative interpersonal theory of depression: A naturalistic study of college roommates. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:778–788. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:279–294. doi: 10.1177/0265407596132007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Goldston D. Cognitive and social cognitive development of depressed children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:388–392. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEvoy JP, Asher SR. When friends disappoint: Boys’ and girls’ responses to transgressions of friendship expectations. Child Development. 2012;83:104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson L, Dorta KP, Moreau D, Weissman MM. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. 2. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Rubin KH, Erath S, Wojslawowicz JC, Buskirk A. Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 2: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ. Moderators of peer contagion: A longitudinal examination of depression socialization between adolescents and their best friends. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:159–170. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Spirito A. Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: Factors that alter or add to peer influence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:287–298. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J. Self-regulatory perseveration and the depressive self- focusing style: A self-awareness theory of reactive depression. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:122–138. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.102.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, Andrews J, Lewinsohn P, Hops H. Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;2:122–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.2.2.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73:1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Damen W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Mette RA, Rose AJ. Conversational self-focus in adolescent friendships: Observational assessment of an interpersonal process and relations with internalizing symptoms and friendship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28:1263–1297. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.10.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Rose AJ. The “cost of caring” in youths’ friendships: Considering associations among social perspective taking, co-rumination, and empathetic distress. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1792–1803. doi: 10.1037/a0025309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Davila J. Excessive reassurance seeking, depression, and interpersonal rejection: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:762–775. doi: 10.1037/a0013866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Jr, Wenzlaff RM, Krull DS, Pelham BW. Allure of negative feedback: Self-verification strivings among depressed persons. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:293–306. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Wenzlaff RM, Tafarodi RW. Depression and the search for negative evaluations: More evidence of the role of self-verification strivings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:314–317. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyber E, McClure FH. Interpersonal process in therapy: An integrative model. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons KA, Joiner TE. Reassurance seeking and negative feedback seeking. In: Dobson KS, Dozois DJ, editors. Risk factors in depression. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. pp. 429–446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the Children’s Depression Inventory: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM. Psychological adjustment and experiences with peers during early adolescence: Reciprocal, incidental, or unidirectional relationships? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:187–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00910730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrip AM, Malcom KT, Jenson-Campbell LA. With a little help from your friends: The importance of high-quality friendship on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development. 2008;17:832–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman K. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:42–64. [Google Scholar]