Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions account for the largest proportion of cases resulting in early separation from the US Navy. This study evaluates the impact of the Spine Team, a multidisciplinary care group that included physicians, physical therapists, and a clinical psychologist, for the treatment of active-duty service members with work-disabling, nonspecific low back pain at the Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA, USA. We compared the impact of the introduction of the Spine Team in limiting disability and attrition from work-disabling spine conditions with the experience of the Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA, USA, where there is no comparable spine team.

Questions/purposes

Is a multidisciplinary spine team effective in limiting disability and attrition related to work-disabling spine conditions as compared with the current standard of care for US military active-duty service members?

Methods

This is a retrospective, pre-/post-study with a separate, concurrent control group using administratively collected data from two large military medical centers during the period 2007 to 2009. In this study, disability is expressed as the proportion of active-duty service members seeking treatment for a work-disabling spine condition that results in the assignment of a first-career limited-duty status. Attrition is expressed as the proportion of individuals assigned a first-career limited-duty status for a work-disabling spine condition who were referred to a Physical Evaluation Board. We analyzed 667 individuals assigned a first-career limited-duty for a work-disabling spine condition between 2007 and 2009 who received care at the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth or Naval Medical Center San Diego.

Results

Rates of first-career limited-duty assignments for spine conditions decreased from 2007 to 2009 at both sites, but limited-duty rates decreased to a greater extent at the intervention site (Naval Medical Center Portsmouth; from 8.5 per 100 spine cases in 2007 to 5.1 per 100 cases in 2009, p < 0.001) as compared with the control site (Naval Medical Center San Diego; 16.0 per 100 spine cases in 2007 and 14.1 per 100 cases in 2009, p = 0.38) after the Spine Team was implemented in 2008. The risk of disability was lower at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego for each of the 3 years studied (in 2007, the relative risk was 0.53 [95% confidence limit {CL}, 0.42–0.68; p < 0.001]) indicating a protective effect of Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in limiting disability (in 2008, it was 0.58 [95% CL, 0.45–0.73; p < 0.001] and in 2009 0.34 [95% CL, 0.27–0.47; p < 0.001]); the relative risk improved in 2009 after the introduction of the Spine Team at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth. There were no differences observed in rates of attrition from the period before the introduction of the Spine Team to after at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, and no overall differences could be statistically detected between the two sites.

Conclusions

This study provides suggestive evidence that a multi-disciplinary Spine Team may be effective in limiting disability. No conclusion can be drawn about the Spine Team’s effectiveness in limiting attrition. Additional study is warranted to examine the effect of the timing of the introduction of multidisciplinary care for work-disabling spine conditions.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4328-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Work-disabling spine conditions constitute one of the leading causes of disability and work loss in industrialized countries [16]. Recent studies found that musculoskeletal conditions accounted for the largest proportion of cases resulting in early separation from the Navy [6, 10]. Spine-related conditions are among the most common musculoskeletal problems reported by active-duty service members. Spine conditions deplete the military of trained, experienced personnel [4, 5, 20, 24].

Recent advances in civilian management of spine conditions hold great promise for the military to limit disability and attrition. Numerous civilian studies have shown that coordinated, multidisciplinary care in the sub-acute stage of a spine condition (between 4 and 12 weeks) can be effective in limiting return to work delays and disability [8, 9, 11, 19, 23]. Based on the evidence from prior collaborative research, the investigators implemented the “Backs to Work” study at the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, VA, USA, an inception cohort with a pilot, nested randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary care [7, 15]. The purpose of the study was to identify selected risk factors that predicted delayed return to duty in service members with spine conditions and to assess the feasibillity of conducting a larger study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of an inter-disicplinary intervention to reduce attrition. As part of the implementation of this study, a multi-disciplinary spine team was formed at the Departments of Orthopedics and Physical Therapy at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth. This team was composed of physicians, physical therapists, and psychologists (the Spine Team). The study found that the multi-disciplinary treatment program was effective in improving subjects’ self-perception of disability with self-perception directly associated with recovery and return to work in the acute stage. The study also found that psychological factors can predict delayed recovery [7, 15]. The previous study did not examine the effect of the multi-disciplinary treatment on prolonged disability and attrition. This study seeks to build on the previous work by analyzing administratively collected health data that have the potential for demonstrating these effects.

Multidisciplinary programs for the management of spine conditions have not yet been standardized throughout the Military Health System. The goal for the Spine Team is to implement evidence-based care and return service members to active duty as soon and as safely as possible and to limit disability and reduce attrition. The unified electronic medical recordkeeping system used by the Department of Defense provides the opportunity to evaluate the difference in disability and attrition before and after the implementation of the Spine Team. The specific objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of the Spine Team on the rate of limited duty (LIMDU) and Physical Evaluation Board (PEB) assignments for service members seeking treatment for spine conditions. This study compares yearly rates of LIMDU and PEB assignments for service members with spine conditions before, during, and after the creation of the Spine Team at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth compared with the Naval Medical Center San Diego, CA, USA, where no multi-disciplinary spine care has been implemented.

This study attempts to answer the following questions: Do sites that use an integrated, multidisciplinary treatment team, as represented by the Spine Team, limit disability (expressed as LIMDU) among active-duty service members with work-disabling spine conditions? Do sites that use an integrated, multidisciplinary treatment team, as represented by the Spine Team, limit attrition (expressed as PEB) related to work-disabling spine conditions?

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

The study design is a retrospective, pre-/post-comparison with a concurrent control group. The intervention being evaluated is the Spine Team, implemented at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in 2008. The control is the standard of care provided at the Naval Medical Center San Diego. Subjects were not randomized between the intervention and control arms, because the intervention took place in Portsmouth, VA, and the control was located at San Diego, CA. The population under study consisted of all US Navy and US Marine Corps service members aged 18 to 64 years of age seeking care for a work-disabling spine condition at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and Naval Medical Center San Diego. Data were collected for the years 2007, 2008, and 2009 to evaluate before and after effects of the introduction of the Spine Team at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and to compare the overall effect of the Spine Team with the currently available standard of care represented at Naval Medical Center San Diego.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

From 2007 to 2009, there were 7313 first-career LIMDU assignments made at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and Naval Medical Center San Diego collectively. Of these, 737 cases involved spine conditions (defined as sprains and strains involving the back and all other spine injuries that did not involve the central nervous system, vertebral fractures, or the result of congenital disorders). For this article, we limit our following analyses to only the 667 limited-duty assignments made through the two clinical departments that are primarily responsible for handling spine-related issues, the Orthopedics and Neurosurgery Departments.

Women account for approximately 18% of the cases. Personnel ages 18 to 25 years represent approximately 35%, those between 26 and 35 years account for approximately 40% of the cases, and those 36 years and older account for the remaining 25%. The majority of the cases are junior enlisted personnel (E3–E6) accounting for approximately 85% of the assignments. There was a higher proportion of Marine Corps personnel with first-career LIMDU assignments at San Diego (35%) than at Portsmouth (8%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals assigned a first-career limited duty for work-disabling spine condition, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and Naval Medical Center San Diego, 2007–2009, US Navy and Marine Corps active-duty service members (n = 667)

| Year | Gender | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (n = 392) |

Naval Medical Center San Diego (n = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Female | 29 (18%) | 12 (14%) |

| Male | 128 (82%) | 72 (86%) | |

| Not recorded | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2008 | Female | 26 (18%) | 16 (16%) |

| Male | 117 (82%) | 80 (82%) | |

| Not recorded | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| 2009 | Female | 15 (16%) | 15 (16%) |

| Male | 77 (84%) | 77 (82%) | |

| Not recorded | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| Year | Age (years) | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (n = 392) |

Naval Medical Center San Diego (n = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 18–25 | 52 (33%) | 33 (39%) |

| 26–35 | 61 (39%) | 28 (33%) | |

| 36–45 | 37 (24%) | 18 (21%) | |

| 46–55 | 6 (4%) | 5 (6%) | |

| 56–65 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2008 | 18–25 | 40 (28%) | 36 (37%) |

| 26–35 | 65 (45%) | 37 (38%) | |

| 36–45 | 34 (24%) | 21 (22%) | |

| 46–55 | 4 (3%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 56–65 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2009 | 18–25 | 28 (30%) | 39 (41%) |

| 26–35 | 28 (30%) | 39 (41%) | |

| 36–45 | 32 (35%) | 12 (13%) | |

| 46–55 | 4 (4%) | 3 (3%) | |

| 56–65 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Year | Pay grade | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (n = 392) |

Naval Medical Center San Diego (n = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | E2 | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| E3 | 18 (11%) | 19 (23%) | |

| E4 | 26 (17%) | 15 (18%) | |

| E5 | 55 (35%) | 21 (25%) | |

| E6 | 32 (20%) | 16 (19%) | |

| E7 | 14 (9%) | 5 (6%) | |

| E8 | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | |

| O1 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O2 | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O3 | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| O4 | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | |

| O5 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| 2008 | E1 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| E2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| E3 | 18 (11%) | 19 (23%) | |

| E4 | 29 (18%) | 22 (26%) | |

| E5 | 46 (29%) | 23 (27%) | |

| E6 | 21 (13%) | 20 (24%) | |

| E7 | 20 (13%) | 5 (6%) | |

| E8 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| E9 | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | |

| O1 | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| O2 | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O3 | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | |

| O4 | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| O5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2009 | E1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| E2 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | |

| E3 | 13 (14%) | 24 (26%) | |

| E4 | 18 (20%) | 18 (19%) | |

| E5 | 21 (23%) | 29 (31%) | |

| E6 | 24 (26%) | 12 (13%) | |

| E7 | 11 (12%) | 6 (6%) | |

| E8 | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| E9 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| O1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O2 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O3 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| O4 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| O5 | 0 (0%) | (0%) |

| Year | Service branch | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (n = 392) |

Naval Medical Center San Diego (n = 275) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Marine Corps | 5 (3%) | 26 (31%) |

| Navy | 152 (97%) | 58 (69%) | |

| 2008 | Marine Corps | 10 (7%) | 37 (38%) |

| Navy | 132 (92%) | 60 (62%) | |

| 2009 | Marine Corps | 9 (10%) | 36 (38%) |

| Navy | 83 (90%) | 58 (62%) |

Approach to Evaluating Spine Team Effectiveness

We evaluated the effect of the Spine Team in two ways: (1) assessing the effect of the Spine Team on disability, defined for the purposes of this article as the assignment of a limited-duty status among those active-duty service members seeking care for a work-disabling spine condition; and (2) attrition, defined for the purposes of this article as the rate at which active-duty service members on a limited-duty status for a work-disabling spine condition are referred to a PEB because of their medical condition. PEBs are the administrative procedures used by the US military to consider early separation from service.

We formulated four specific, testable hypotheses, two of which related to disability and the other two relating to attrition. To assess the effect of the Spine Team on limiting disability, we posed the following two hypotheses: (1) rates of disability at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth would show a pre-/post-effect of the introduction of the Spine Team in 2008; that is to say, rates of disability would be lower in 2009 as compared with rates of disability in 2007; (2) rates of disability at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth would show a differential decrease after the introduction of the Spine Team in 2008 as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego. To assess the effect of the Spine Team on limiting attrition, we posed the following hypotheses: (3) rates of attrition would decrease over time at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth after the introduction of the Spine Team; and (4) rates of attrition would show a differential decrease after the introduction of the Spine Team as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego.

Data Sources

The US military’s electronic medical recordkeeping system was accessed to count the total number of individuals presenting for musculoskeletal issues at the two sites. We then identified all of those individuals who were assigned LIMDU for their index musculoskeletal disorders between 2007 and 2009. A similar electronic system, used by the US military to track disability, was used to identify those cases for which an active-duty service member on limited duty was referred to a PEB. In this way, we were able to generate annual rates. A detailed discussion of the construction of the rates used in the study can be found in Appendix 1 (Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR®.).

Statistical Analysis

We examined rates over time and between sites. We used a Cochran-Armitage Test for trend [3] to evaluate for changes in rates over time. To compare rates between sites, we calculated a relative risk and evaluated if the relative risk was different from one by an amount greater than would be expected from chance variation alone. We adjusted for the presence of potential confounders by means of direct adjustment.

Results

The Effect of the Spine Team on Disability Related to Work-disabling Spine Conditions

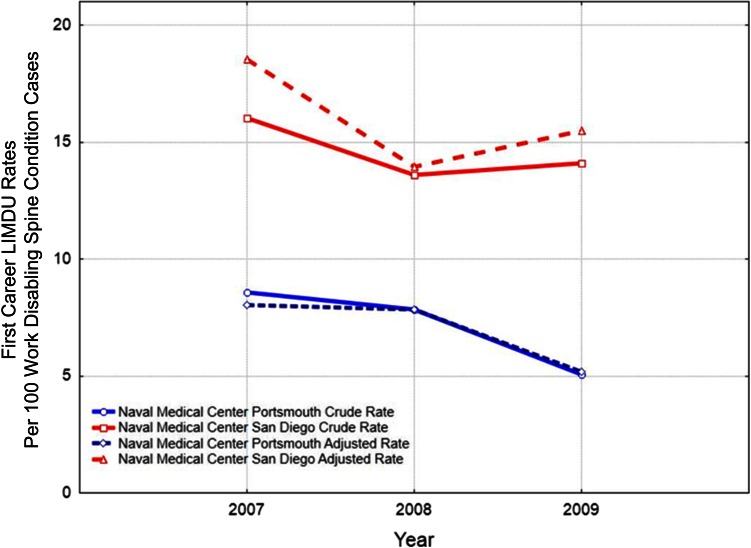

Study data show suggestive evidence of the effectiveness of the Spine Team in limiting disability associated with work-disabling spine conditions. The analysis found that annual rates of first-career LIMDU for spine conditions were lower at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth for years 2007, 2008, and 2009 as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego. Despite this, annual rates of disability decreased after the introduction of the Spine Team at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth to a greater extent as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego. At Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, the annual rate of first-career LIMDU assignments was 8.5 per 100 spine cases in 2007, 7.8 per 100 in 2008, and 5.1 per 100 cases in 2009. This decrease was statistically significant (p < 0.001), At Naval Medical Center San Diego, where there was no such introduction of a spine team, the annual rate of first-career LIMDU assignments was 16.0 per 100 spine cases in 2007, 13.0 per 100 in 2008, and 14.1 per 100 cases in 2009. There was no statistically detectable change in rates of disability observed over time at Naval Medical Center San Diego (p = 0.38). Comparing between sites for each year, the relative risk of disability between Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and Naval Medical Center San Diego in 2007 was 0.53 (95% confidence limit [CL], 0.42–0.68; p < 0.001), in 2008 was 0.58 (95% CL, 0.45–0.73; p < 0.001), and in 2009 was 0.34 (95% CL, 0.27–0.47; p << 0.001) indicating a protective effect of Naval Medical Center Portsmouth overall and an improvement in limiting disability in 2009 after the introduction of the Spine Team. We examined if these observations changed considering active-duty service member age and service branch membership as a potential confounding factor. Using direct adjustment, the pattern of differences between Naval Medical Center San Diego and Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and over time remained nearly the same after statistical adjustment for service branch membership (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

This figure shows the effect of statistically adjusting the rates of first-career LIMDU for the possible confounding effects of branch of service membership (Navy versus Marine Corps) and subject age. Adjusted rates are represented as dashed lines, whereas crude rates are represented as solid lines. Rates are adjusted for age and branch of service membership. NMCP = Naval Medical Center Portsmouth; NMCSD = Naval Medical Center San Diego.

The Effect of the Spine Team on Attrition Related to Work-disabling Spine Conditions

Study data show an unclear picture of the effect of the Spine Team on attrition. Of the 157 service members assigned first-career LIMDU status in 2007 at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, 41 converted to a PEB, representing a risk of 26 conversions per 100 LIMDU cases. This risk decreased in 2008 to 19 conversions per 100 LIMDU cases and increased to 36 per 100 LIMDU cases in 2009. At Naval Medical Center San Diego, of the 84 service members assigned first-career LIMDU status in 2007, 34 converted to a PEB, representing a risk of 45 conversions per 100 LIMDU cases. The risk of PEB conversion decreased to 16 conversions per 100 LIMDU cases in 2008 and then increased to 27 conversions per 100 LIMDU cases in 2009 (Table 2). The risk of conversion from a LIMDU to a PEB is lower at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in 2007, before the introduction of the Spine Team, as compared with Naval Medical Center San Diego (relative risk, 0.59; 95% confidence limit [CL], 0.41-0.84; p < 0.01). On the other hand, the study data show that the risk of conversion from a LIMDU to a PEB at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in 2009, after the introduction of the Spine Team, could not be distinguished from that of Naval Medical Center San Diego (relative risk, 1.4; 95% CL, 0.86–2.00; p = 0.21).

Table 2.

Annual unadjusted risk of conversion from a limited-duty status for a work-disabling spine condition to a Physical Evaluation Board, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth and Naval Medical Center San Diego, 2007–2009, US Navy and Marine Corps active-duty service members

| Cohort year | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth | Naval Medical Center San Diego | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-career limited-duty cases | Cases converted to a Physical Evaluation Board | Risk of conversion (conversions per 100 limited-duty cases) | First-career limited-duty cases | Cases converted to a Physical Evaluation Board | Risk of conversion (conversions per 100 limited-duty cases) | Relative risk (95% confidence limit) p value |

|

| 2007 | 157 | 41 | 0.26 | 84 | 38 | 0.45 | 0.59 (0.41–0.84) p < 0.01 |

| 2008 | 143 | 27 | 0.19 | 97 | 16 | 0.16 | 1.2 (0.67-2.05); p = 0.58 |

| 2009 | 92 | 34 | 0.36 | 94 | 26 | 0.27 | 1.4 (0.86 – 2.00); p = 0.21 |

Although the Spine Team was introduced at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in 2008, we noted that of the 34 Naval Medical Center Portsmouth service members who received first-career LIMDU assignments in 2009 and converted to a PEB, 15 did not receive care from the Spine Team before their PEB conversion, and of those 19 service members who received care from the Spine Team before their PEB conversion, seven received care only after 12 months of onset of the spine condition, three received care only after surgical intervention, and nine service members received care from the Spine Team within 9 months of onset of the spine condition. Conversely, of the 58 service members who were non-converters, 32 service members received care from the Spine Team within 3 months of onset of their spine condition problems.

Discussion

Work-disabling spine conditions are among the most common causes of disability and work loss in industrialized countries [16]. Approaches in civilian workplace settings that have coordinated, multidisciplinary care in the sub-acute stage of a spine condition (between 4 and 12 weeks) can limit return to work delays and disability [8, 9, 11, 19, 23], and some analogous pilot projects in the military have evaluated these approaches in the armed forces of the United States, but that work has been preliminary in nature [7, 15]. We therefore sought to evaluate the effect of the introduction of coordinated, multidisciplinary care for work-disabling, non-traumatic, musculoskeletal conditions in the US Navy. Although this study was prompted by the US Navy’s initiative to limit attrition for medical reasons, the findings of this study can useful to both military and civilian sectors because the coordinated, uniform method of delivery of care and recordkeeping in the military helps reduce the number of possible factors that may confound the findings in observational studies. We found that spine-related limited-duty rates decreased at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth after the introduction of the Spine Team but that rates of conversion to a PEB varied from year to year and did not statistically differ between the two sites.

There are three important study limitations that may influence the conclusion that the Spine Team was responsible for the lowering LIMDU rates at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth. First, this is an observational, nonrandomized intervention study. The use of Naval Medical Center San Diego as a concurrent control helps strengthen the inference that the coordinated care was responsible for the decrease in limited-duty rates, but because of the observational nature of the study, the reader cannot conclude that the intervention was solely responsible for the observed effect. The second limitation is that there were proportionately more US Marines followed at San Diego as compared with Portsmouth, and because US Marines are exposed to different kinds of physical risks than sailors, the possibility for confounding exists when comparing rates. We found that adjusted limited-duty rates were indeed lower at Portsmouth as compared with San Diego after the introduction of the Spine Team. The third limitation is the absence of a specific code identifying that sailors at Portsmouth were under the care of the Spine Team. This introduces the possibility of misclassification bias. There are two possible interpretations for the reader if misclassification in this study is present. If all US Sailors and Marines at Portsmouth were indeed treated with the Spine Team after the introduction of the program, then the observed difference would reflect, in theory, the effect of coordinated care in reduction of limited duty. On the other hand, if none of the Sailors and Marines at Portsmouth were treated by the Spine Team, then the observed reduction in limited duty would have to be attributable to some other condition or variable not captured by the study.

Although we found the risk of a conversion from a limited-duty status to a PEB did not differ between the control and intervention sites, there are two important limitations to the study that may color this conclusion. The first limitation is that there may have been unrecorded differences in the criteria used by clinicians at San Diego and Portsmouth to assign limited duty to active-duty members and the criteria by which these cases are converted to a PEB. Such an effect could have occurred if the Spine Team used more stringent criteria for the assignment of first-career LIMDU designation. This would imply that only the most severe cases presenting for spine care would receive first-career LIMDU status, and these more severe cases are more likely to convert to PEBs. The second important limitation has to do with changes in staffing at those clinics assigning limited duty and PEBs. Because spine surgeons are those who dictate PEBs for a spine condition, changes in staffing resulting from deployments and rotation of spine surgeons through San Diego and Portsmouth may have affected the criteria by which PEBs were assigned and consequently the risk of PEB dictation.

There is evidence from studies conducted in other occupational settings that multidisciplinary care is effective in preventing disability [1, 2, 8, 9, 11–14, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25]. The findings of this study are consistent with those from the civilian sector. In light of these findings, the following is worth considering regarding the effectiveness of the Spine Team implementation: it was apparent that there was a delay in the initiation of care for spine conditions. That is to say, Spine Team coordinated care at Portsmouth was, on occasion, initiated after the active-duty service member had already received a first-career LIMDU assignment for the spine condition; suggesting the spine condition was already chronic before the Spine Team saw the patient. One other study of US Navy personnel found that coordinated multidisciplinary care resulted in improved activities of daily living scores as compared with usual care among active-duty service members with work-limiting low back pain, but that study limited its follow-up to six months post-intervention [7]. This wider, observational study was able to look at disability and attrition, expressed as LIMDU assignments and PEBs, for a minimum of 1 year after intervention for all subjects.

Numerous studies suggest the importance of early care with clear guidelines for how care should progress in instances of delayed recovery [1, 2, 8, 9, 11–14, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25]. When care is initiated in the chronic stage of back pain, poorer outcomes, including higher rates of disability (and PEB referral), are expected, regardless of whether a multidisciplinary approach is implemented. It was noted in these data that earlier contact with the Spine Team resulted in better outcomes, including lowered rates of conversion to a PEB. Gaps in patterns of care were difficult to explain. One possibility is that service members with spine conditions received follow-up conservative care from their operational medical team, which is not always reflected in the Composite Health Care System records. Another possibility is that the service members chose not to seek treatment.

To fully appreciate the impact of the Spine Team, several changes should be considered including: development of a system for triaging service members with spine conditions to the Spine Team for care early after onset of injury; use of an evidence-based algorithm to allocate treatment; use of specific coding by all members of the Spine Team to differentiate care from that of other providers; and use of a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code for patient education (CPT 98960) because reassurance and information have been demonstrated to be effective for spine conditions [15, 21]. This code is in use by other clinicians in the Composite Health Care System records but not consistently for spine cases; and cases that present with a premorbid psychological or psychiatric diagnosis should be identified because different outcomes may be expected.

Data for this study suggest that multi-disciplinary care such as that offered by the Spine Team may have contributed to the lowering the risk of service members being assigned to LIMDU status. Multidisciplinary care achieves its effect by addressing both physical and psychological factors associated with recovery from a spine condition. The unclear effect of the Spine Team in limiting attrition may have to do with the non-uniform introduction of multidisciplinary care during the course of the active-duty service member’s condition, where the Spine Team was introduced early in some cases and in the late, chronic stage in other cases. We recommend that the timing of the introduction of multidisciplinary care in this study population be studied further. We also recommend that additional work be done to develop an algorithm where service members with spine conditions who are at risk of being placed on LIMDU, referred to a PEB, and ultimately subject to attrition be referred to the Spine Team before their condition becomes chronic. The results of this study indicate that a coordinated multidisciplinary care seems to decrease temporary and long-term disability in a military population, similar to what has been found in the civilian population.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Epidemiology Data Center of the US Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center for their support for this study and wish to recognize Michelle Barnes, Epidemiologist, for her work generating data sets for this study. The following individual contributed to the data management and preparation of the manuscript: Mandi Gibbons MS, NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. The following individuals contributed to the project management of this study: Samantha Russell and Darlene Harbour, Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute. The following contributed critical review of the manuscript: Stewart Kerr MD, and Jason Zook MD.

Footnotes

One of the authors (MC) certifies that he received, in the form of salary support, an amount between USD 10,000 and USD 20,000 during the study period for the purpose of conducting the study. One of the authors (RH) certifies that he received, in the form of salary support, an amount between USD 10,000 and USD 50,000 during the study period for the purpose of conducting the study. One of the authors (SSW) certifies that she received, in the form of salary support, an amount between USD 10,000 and USD 20,000 during the study period for the purpose of conducting the study. One of the authors (MN) certifies that she received, in the form of salary support, an amount between USD 10,000 and USD 20,000 during the study period for the purpose of conducting the study. Funding was provided by the US Navy Bureau of Medicine contracting through Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, contract number 2011.029.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the Naval Medical Hospital Portsmouth, Portsmouth, VA, USA.

References

- 1.Accident Compensation Corporation. New Zealand Acute Low Back Pain Guide, Incorporating the Guide to Assessing Psychosocial Yellow Flags in Acute Low Back Pain. 2004. Available at: http://www.acc.co.nz/PRD_EXT_CSMP/groups/external_communications/documents/guide/prd_ctrb112930.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- 2.Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Loisel P, van Mechelen W. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32:291–298; discussion 299–300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Armitage P. Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics. 1955;11:375–386. doi: 10.2307/3001775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz SM, Feuerstein M, Lopez MS, Peck CA., Jr Occupational back disability in US Army personnel. Mil Med. 1999;164:412–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnker BK, Telfair T, McGinnis JA, Malakooti MA, Sack DM. Analysis of Navy Physical Evaluation Board diagnoses (1998-2000) Mil Med. 2003;168:482–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth-Kewley S, Schmied EA, Highfill-McRoy RM, Larson GE, Garland CF, Ziajko LA. Predictors of psychiatric disorders in combat veterans. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campello MA, Ziemke GW, Hiebert R, Weiser S, Brinkmeyer M, Fox BA, Dail J, Kerr S, Hinnant I, Nordin M. Implementation of a multidisciplinary program for active duty personnel seeking care for low back pain in a US Navy Medical Center: a feasibility study. Mil Med. 2012;177:1075–1080. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekelle P, Owens DK. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R, Shekelle P, Qaseem A, Owens DK. Correction: Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:247–248. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-3-200802050-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen SP, Nguyen C, Kapoor SG, Anderson-Barnes VC, Foster L, Shields C, McLean B, Wichman T, Plunkett A. Back pain during war: an analysis of factors affecting outcome. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1916–1923. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S. Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines. Spine J. 2010;10:514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demetrious J. Guidelines in the evaluation and management of low back pain. N C Med J. 2008;69:175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feuerstein M, Hartzell M, Rogers HL, Marcus SC. Evidence-based practice for acute low back pain in primary care: patient outcomes and cost of care. Pain. 2006;24:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guevara-Lopez U, Covarrubias-Gomez A, Elias-Dib J, Reyes-Sanchez A, Rodriguez-Reyna TS. Practice guidelines for the management of low back pain. Consensus Group of Practice Parameters to Manage Low Back Pain. Cirugia y Cirujanos. 2011;79:264–279, 286–302. [PubMed]

- 15.Hiebert R, Campello MA, Weiser S, Ziemke GW, Fox BA, Nordin M. Predictors of short-term work-related disability among active duty US Navy personnel: a cohort study in patients with acute and subacute low back pain. Spine J. 2012;12:806–816. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoy DG, Smith E, Cross M, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth FM, Buchbinder R, Woolf AD, Driscoll T, Brooks P, March LM. Reflecting on the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions: lessons learnt from the global burden of disease 2010 study and the next steps forward. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:4–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–2094. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Burton AK, Waddell G. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain in primary care: an international comparison. Spine. 2001;26:2504–2513; discussion 2513–2514. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lindstrom I, Ohlund C, Eek C, Wallin L, Peterson LE, Fordyce WE, Nachemson AL. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: a randomized prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Phys Ther. 1992;72:279–290; discussion 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Litow CD, Krahl PL. Public health potential of a disability tracking system: analysis of U.S. Navy and Marine Corps physical evaluation boards 2005–2006. Mil Med. 2007;172:1270–1274. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.172.12.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (‘yellow flags’) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91:737–753. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordin M, Balague F, Cedraschi C. Nonspecific lower-back pain: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:156–167. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000198721.75976.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiltenwolf M, Buchner M, Heindl B, von Reumont J, Muller A, Eich W. Comparison of a biopsychosocial therapy (BT) with a conventional biomedical therapy (MT) of subacute low back pain in the first episode of sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1083–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Songer TJ, LaPorte RE. Disabilities due to injury in the military. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(Suppl):33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:794–819. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.