Abstract

Solitary Fibrous Tumors (SFT) are rare neoplasms first described in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin. SFT's have mesenchymal rather than mesothelial origin. They arise mostly from serous membranes, although they also originate in other regions such as: the urogenital system, mediastinal space, lungs, vulva, orbit, thyroid, nasopharyngeal region, larynx, salivary glands. SFT of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are extremely rare. To the year 2014 only 33 cases were reported in English literature.

Patients and methods

We present a case of 58-year-old man with solitary fibrous tumor localized in the right nasal cavity. The patient presented with an 18-month history of epistaxis and right epiphora. He also reported unilateral right-sided nasal obstruction over the last 6 months.

Results

CT disclosed a large, homogeneous mass in the nasal cavity infiltrating and destroying nasal septum, turbinates, occupying right maxillary sinus, right ethmoid, extending to the right frontal sinus and right orbit. The infiltration of the right oculus was suspected. Biopsy revealed fibrocytes and histiocytes proliferation with rich vascularization. There was no evidence of histological malignancy. Pathology results were significant for SFT.

Conclusion

The tumor was excised by means of right lateral rhinotomy. Neither the extension to the right maxillary sinus nor the orbital floor infiltration was seen intraoperatively despite the fact, that it was observed in computed tomography before the surgery. The patient had a 5.5-year follow up after surgery, radiological examination showed no recurrence.

Keywords: Solitary fibrous tumor, Nasal cavity, Paranasal sinuses

1. Introduction

Solitary Fibrous Tumors (SFT) are rare neoplasms first described in 1931 by Klemperer and Rabin.1 Authors presented five cases of primary pleural localization. SFT's have mesenchymal rather than mesothelial origin. They arise mostly from serous membranes, although they also originate in other regions such as: the urogenital system, mediastinal space, lungs, vulva, orbit, thyroid, nasopharyngeal region,2 larynx, salivary glands.3 SFT of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are extremely rare. To the year 2014 only 33 cases were reported in English literature. SFT most commonly occurs in adults between the fourth and eighth decades. Pleural cases are malignant in 13–23%, whereas extrapleural are mostly benign. The average diameter in the moment of diagnosis is 3–5 cm.

Initially the tumor presents as an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed soft tissue mass. After that, due to the tumor growth, such symptoms occur: nasal obstruction, epistaxis, hyposmia, rhinorrhoea, sinusitis, headaches, facial pain, exophthalmos, resorption of the surrounding bone structures.

The diagnosis of SFT is based on the clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography and histologic analysis with immunohistochemistry. SFT are treated by complete surgical excision.4

Almost all tumors exhibit immunoreactivity for CD 34.5 Other common markers include CD 99, Bcl-2 protein and vimentin. Vimentin is considered to be non-specific, because it is expressed by most mesenchymal and many epithelial neoplasms. SFT's do not show immunoreactivity for keratin, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100 protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein and carcinoembryonic antigen.6

2. Case report

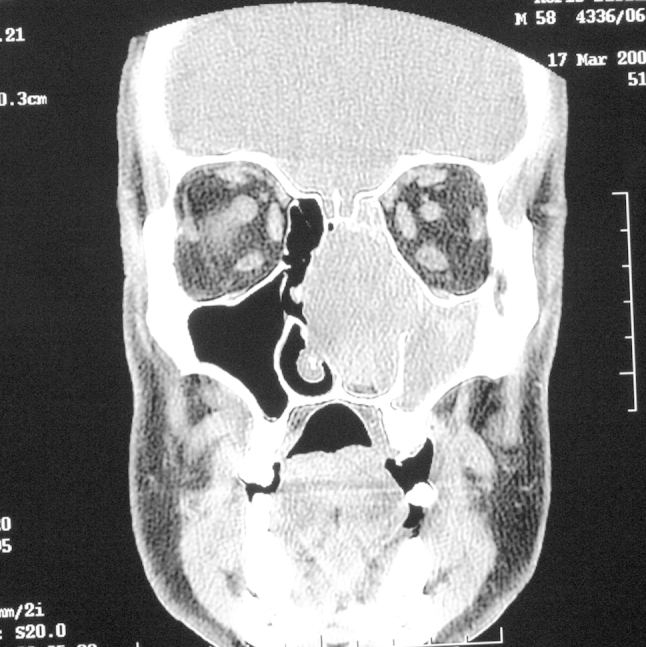

A 58-year-old man presented with an 18-month history of epistaxis and right epiphora. He also reported unilateral right-sided nasal obstruction over the last 6 months. The patient was otherwise healthy and in good general condition. ENT examination revealed a smooth white mass in the right nasal cavity which compressed and deviated the nasal septum. Ophthalmological examination showed low grade retinal atherosclerotic angiopathy. The laboratory findings were normal. The Waters view X-ray revealed radiopaque lesion in the right maxillary sinus. Subsequently performed computed tomography disclosed a large, homogeneous mass in the nasal cavity infiltrating and destroying nasal septum, turbinates, occupying right maxillary sinus, right ethmoid, extending to the right frontal sinus and right orbit. The infiltration of the right oculus was suspected (Fig. 1). Biopsy revealed fibrocytes and histiocytes proliferation with rich vascularization. There was no evidence of histological malignancy. Pathology results were significant for SFT. During the biopsy a massive bleeding occurred, which was treated by an electrocoagulation.

Fig. 1.

Coronal CT scan showing a mass in the nasal cavity, maxillary sinus, ethmoid, extending to the frontal sinus and orbit on the right side. The scan is inverted.

After procedures described above the patient was referred to the Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery Ward. Once again he was thoroughly examined and the excision of the tumor under a general anesthesia was performed. The patient underwent the right lateral rhinotomy. During a surgery the tumor occupying nasal cavity, disfiguring nasal septum into left side was exposed. Neither the extension to the right maxillary sinus nor the orbital floor infiltration was seen. Because of the frontal sinus wall erosion the right frontal sinus drainage was carried out. A 5.5 × 4 × 3 cm tumor was excised en-block. Although no excessive bleeding was observed, temporary nasal packing was placed for 48 h. The postoperative period was uneventful, the frontal sinus drainage was removed after 48 h. The patient had a 5.5-year follow up after surgery. Radiological examination showed no recurrence. Pathological evaluation revealed patterns consistent with SFT. Immunohistochemical studies were strongly positive for CD 34 and negative for desmin and epithelial membrane antigen. Smooth-muscle actin was present in blood vessels walls, whereas S-100 protein was present in a small number of cells.

3. Discussion

SFTs are rare neoplasms that mostly occur as pleural or serosal tumors.1 Their origin is discussed, they are said to grow from mesenchymal rather than the mesothelial tissue. This explains a wide variety of possible sites of occurrence. Although less common than in first described site, they can be found in larynx, hypolarynx, parapharyngeal space, tongue, orbit, lung, vulva, thyroid, infratemporal fossa, paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity.4,7

We found only 33 cases of SFT in nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses published in the English literature. Table 1 presents characteristics of all 34 cases reported so far (19 women, 15 men). The mean age of the patients was 50.4 y (range 30–74 years). The most common clinical symptom was nasal obstruction. The other symptoms reported were epistaxis, rhinorrhoea, hyposmia, exophthalmos. Our patient presented such symptoms as repeated epistaxis and epiphora which were prior to nasal obstruction. Tumors sizes ranged from 1.7 to 8.5 cm, in our case the tumor size was 5.5 × 4 × 3 cm. The authors usually described excised SFTs as pinkish, reddish, white, circular, oval in shape, well-encapsulated fibrous masses with rich vascularization. In this case the tumor was similar.

Table 1.

Published cases of solitary fibrous tumor: Clinical, epidemiological and immunohistochemical characteristics.

| Case no | Study | Age (years) | Sex | Symptoms | Size (cm) | Side | IHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zukerberg et al | 48 | F | NO+ hyposmia | <3 | R | V+ |

| 2 | Zukerberg et al | 45 | F | NO+ nasal congestion | <3 | R | V+ |

| 3 | Witkin & Rosai | 64 | F | NO | ? | L | V+ |

| 4 | Witkin & Rosai | 36 | F | NO+ rhinorrhoea | 7 × 4 × 3 | R | V+ |

| 5 | Witkin & Rosai | 47 | F | NO | 4 × 3.5 | L | V+ |

| 6 | Witkin & Rosai | 55 | M | NO | ? | R | V+ |

| 7 | Witkin & Rosai | 30 | M | NO+ epistaxis+ exophthalmus | ? | NP | V+ |

| 8 | Witkin & Rosai | 62 | M | NO | ? | NP | V+ |

| 9 | Martinez et al | 71 | F | NO+ epistaxis+ rhinorrhoea | ? | R | V+ |

| 10 | Martinez et al | 61 | F | NO+ epistaxis+ exophthalmus | 5.5 × 5 × 1 | R | V+ |

| 11 | Fukunaga et al | 33 | F | NO+ rhinorrhoea | 3.5 | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 12 | Kim et al. | 69 | F | NO+ epistaxis | 5 × 3.8 × 5.3 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 13 | Stringfellow et al | 59 | F | NO+ rhinorrhoea | 5 × 3 × 3 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 14 | Mentzel et al | 31 | F | NO | 1.7 | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 15 | Kessler et al | 54 | M | NO+ epistaxis | 3 × 4 × 5 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 16 | Brunnemann et al | 48 | M | NO | 8 × 4 × 4 | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 17 | Brunnemann et al | 54 | M | NO+ epistaxis | 8 × 3.5 × 2.8 | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 18 | Kohmura et al | 55 | M | NO+ epistaxis | 7 × 3.5 | L | V+ CD34+ |

| 19 | Kohmura et al | 53 | M | NO | ? | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 20 | Morimitsu et al | 61 | F | NO | 5.5 × 3 | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 21 | Morimitsu et al | 51 | F | NO | ? | ? | V+ CD34+ |

| 22 | Alobid et al | 43 | M | NO+ epistaxis+ rhinorrhoea | 6.5 × 3.8 × 3 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 23 | Pasquini et al | 54 | F | NO | ? | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 24 | Eloy et al | 46 | F | NO | ? | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 25 | Abe et al | 49 | F | cephalea | 5 × 3 × 3 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 26 | Corina et al | 63 | F | ON+ hyposmia | ? | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 27 | Morales-Cadena et al | 32 | M | NO+ rhinorrhoea | 5 × 6 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 28 | Jurado-Ramos et al | 38 | F | NO | 7 × 8.5 × 6 | R | V+ CD34+ |

| 29 | Zeitler et al | 70 | M | NO+ epiphora | 6.5 × 4.2 × 2.5 | L | V+ CD34+ BCL-2+ CD99+ |

| 30 | Kodama et al | 74 | M | NO | 4 × 3.2 × 1.8 | L | CD34+ |

| 31 | Smith et al | 48 | M | NO+ rhinorrhoea+ anosmia+ exophthalmos | 7.5 | R | V+ CD34+ BCL-2+ CD99+ |

| 32 | Konstantidinis et al | 47 | F | NO+ epistaxis | 3 × 2 × 1.5 | L | V+ actin+ CD34+ |

| 33 | Nai et al | 54 | M | epistaxis | 6 × 4 × 4 | NP | V+ CD34+ |

| 34 | Present study | 58 | M | NO+ epistaxis+ epiphora | 5.5 × 4 × 3 | R | CD34+ |

No = number; IHC = immunohistochemistry; F = female; M = male; NO = nasal obstruction, R = right; L = left; NP = nasopharynx; ? = not defined; V+ = positive for vimentin; CD34+ = positive for CD34.

During the diagnostic process the importance of imaging examination (computed tomography or MRI) is stressed. It exhibits a mass occupying nasal cavity and/or paranasal sinuses. Depending on the size the nasal septum may be deviated and bony structures damaged. Rarely the tumor can extend to the orbit7,8 and intracranial through the cribriform plate and ethmoid roof7 or can occupy infratemporal8 and pterygomaxillary regions.4

In some cases, the preoperative CT showed bone destruction, but during the surgery no bony defect was seen and the tumor was encapsulated. In our case imaging disclosed orbit and ocular infiltration, which was not observed intraoperatively.3

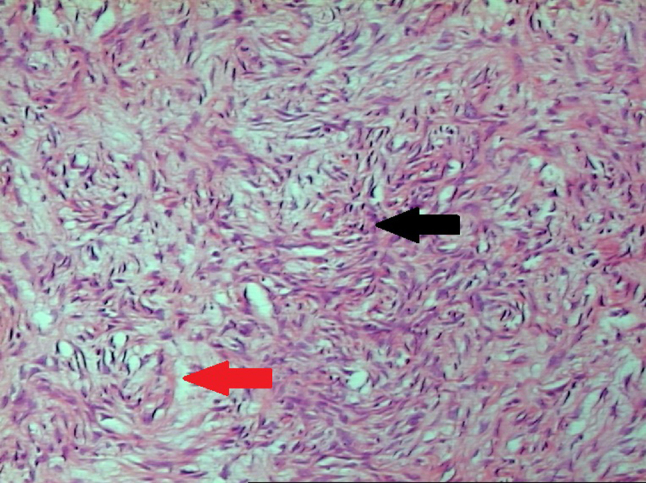

A definitive diagnosis cannot be achieved without biopsy and pathological examination. Microscopically SFTs are described as patternless with haphazard arrangement of plump spindle cells, hypercellular and hypocellular sclerotic foci, stromal hyalinization and a prominent branching vasculature.9 In present case hematoxilin and eosin staining disclosed fascicles of tumor cells (black arrow) in loose and myxoid stroma (red arrow) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing fascicles of tumor cells in loose and myxoid stroma, black arrow-fascicles of cells, red arrow-stroma.

Immunohistochemically most cases were CD 34 and vimentin positive, and S-100 negative. CD 34 is not entirely specific for SFT and express in a variety of spindle cell neoplasms such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans or neural tumors.10 Vimentin is considered to be non-specific marker because it is expressed by most mesothelial and many epithelial neoplasms.6 In our case immunohistochemical analyses were strongly positive for CD 34, weakly positive for smooth-muscle actin, S-100 protein was present in a few cells. The staining was negative for desmin and epithelial membrane antigen.

There are some microscopical features considered to be typical for malignant SFTs. Those are: nuclear atypia, increased cellularity, necrosis, more than 4 mitoses per 10 HPF.11 On the other hand, Zeitler emphasizes that malignant pathology does not imply malignant behavior regarding SFTs localized in nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.7 In our case the pathological malignancy was not observed.

4. Conclusion

We would like to stress that the definitive treatment for SFT is complete resection. After such procedure SFT do not reoccur. All lesions reported in literature were treated by surgical excision. Two patients received a postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy, in one patient the embolization of a nasopharyngeal remnant was performed.2,12 In our case the complete surgical resection was performed and no other treatment was necessary. The patient is free of the tumor for 5.5 years. Surgeon should be aware of the high risk of profuse bleeding during not only surgery but the biopsy as well. Therefore the presence of adequate blood substitutes is necessary.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Klemperer P., Rabin C.B. Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Am J Ind Med. 1931;11:385–412. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witkin G.B., Rosai J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the upper respiratory tract. A report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:842–848. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato J., Asakura K., Yokoyama Y., Satoh M. Solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid gland extending to the parapharyngeal space. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;255:18–21. doi: 10.1007/s004050050015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurado-Ramos A., Ropero Romero F., Cantillo Baños E., Salas Molina J. Minimally invasive endoscopic techniques for treating large, benign processes of the nose, paranasal sinus, and pterygomaxillary and infratemporal fossae: solitary fibrous tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:457–461. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasegawa T., Matsuno Y., Shimoda T., Hasegawa F., Sano T., Hirohashi S. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors: their histological variability and potentially aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1464–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohmura T., Nakashima T., Hasegawa Y., Matsuura H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the paranasal sinuses. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;256:233–236. doi: 10.1007/s004050050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeitler D.M., Kanowitz S.J., Har-El G. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal cavity. Skull Base. 2007;17:239–246. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith L.M., Osborne R.F. Solitary fibrous tumor of the maxillary sinus. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86:382–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zukerberg L.R., Rosenberg A.E., Randolph G., Pilch B.Z., Goodman M.L. Solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:126–130. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199102000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rijn M., Rouse R.V. CD34: a rewiev. Appl Immunohistochem. 1994;2:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallat-Decouvelaere A.V., Dry S.M., Fletcher C.D. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1501–1511. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez V., Jiménez M.L., Cuatrecasas M. Solitary naso-sinusal fibrous tumor. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1995;46:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]