Abstract

Background

Uric acid may be involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension. We investigated the roles of four major hemodynamic parameters of blood pressure, including arterial stiffness, wave reflections, cardiac output (CO), and total peripheral resistance (TPR), in the association between uric acid and central systolic blood pressure (SBP-c).

Methods

A sample of 1303 normotensive and untreated hypertensive Taiwanese participants (595 women, aged 30–79 years) was drawn from a community-based survey. Study subjects’ baseline characteristics, biochemical parameters, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cf-PWV), amplitude of the backward pressure wave decomposed from a calibrated tonometry-derived carotid pressure waveform (Pb), CO, TPR, and SBP-c were analyzed.

Results

In multi-variate analyses adjusted for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, and heart rate, uric acid significantly correlated with Pb and cf-PWV in men, and Pb and TPR in women. The correlation between uric acid and Pb remained significant in men and women when cf-PWV was further adjusted. In the final multi-variate prediction model (model r2 = 0.839) for SBP-c, the significant independent variables included uric acid (partial r2 = 0.005), Pb (partial r2 = 0.651), cf-PWV (partial r2 = 0.005), CO (partial r2 = 0.062), TPR (partial r2 = 0.021), with adjustment for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, and heart rate.

Conclusions

Uric acid was significantly independently associated with wave reflections, which is the dominant determinant of SBP-c. Uric acid was also significantly associated with SBP-c independently of the major hemodynamic parameters.

Keywords: Uric acid, hypertension, arterial stiffness, wave reflection, c-peptide

1. Introduction

An elevated level of serum uric acid may be associated with the development of hypertension [1–3] and hypertension-related target organ damage,[4] especially in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, or obesity. The association of uric acid with hypertension [5, 6] may partly explain the association of hyperuricemia with cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and mortality from heart failure and stroke.[7, 8] In addition, lowering uric acid in the hyperuricemic adolescents with newly diagnosed hypertension or obese prehypertensives may become a therapeutic strategy in the management of hypertension.[9, 10]

How uric acid modulates blood pressure remains unclear.[2, 3] Blood pressure is determined by both steady and pulsatile hemodynamics, including cardiac output, total peripheral resistance, arterial stiffness, and arterial wave reflections.[11–13] Only a few studies investigated the relationship between uric acid and various hemodynamic determinants of blood pressure, with inconsistent or even contradictory results.[14–19] For instance, the association between hyperuricemia and increased arterial stiffness has not been established.[14–19] In addition, a controversial inverse relationship between uric acid and arterial wave reflections in female newly diagnosed, never-treated hypertensives has been reported.[14] Therefore, in this cross-sectional study, we investigated the complex associations of serum uric acid with cardiac output, total peripheral resistance, arterial stiffness, arterial wave reflections, and central aortic systolic blood pressure (SBP-c). Central blood pressure is a more relevant blood pressure measurement and has been shown to predict target organ indices and cardiovascular mortality better than brachial blood pressure. [20]

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The study cohort of 1303 normotensive and untreated hypertensive [brachial systolic blood pressure (SBP-b) >140 mmHg or brachial diastolic blood pressure (DBP-b) >90 mmHg] Taiwanese participants (595 women aged 30–79 years) was drawn from a previous community-based survey conducted in 1992–1993.[21] Baseline comprehensive cardiovascular evaluation included complete medical history and physical examination, carotid artery tonometry, non-directional Doppler flow velocimetry, and echocardiography, as previously described. [21] None of the participants had a previous history of diabetes mellitus, angina pectoris, or peripheral vascular disease, and none had clinical or echocardiographic evidence of other significant cardiac diseases. All participants gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University.

2.2. Blood pressure variables

SBP-b and DBP-b were measured manually using a mercury sphygmomanometer and a standard-sized cuff (13×50 cm) by experienced cardiologists. Two measurements separated by at least 5 min were taken from the right arm of participants after they were seated for at least 5 min. A third measurement was taken when the difference of SBP-b between the first two measurements was greater than 10 mmHg. Reported blood pressure values represented the average of the two or three consecutive measurements. Brachial pulse pressure (PP-b) was calculated as (SBP-b – DBP-b) and brachial mean blood pressure was calculated as [DBP-b + (PP-b/3)]. SBP-c, DBP-c, and PP-c were derived from the ensemble averaged right common carotid artery pressure waveform calibrated to DBP-b and mean blood pressure. Carotid artery pressure waveforms were registered noninvasively using an arterial tonometer.[22]

2.3. Arterial stiffness

Carotid femoral pulse wave velocity (cf-PWV, current gold standard for arterial stiffness) was measured using sequential non-directional Doppler (Parks model 802; Parks Medical Electronics, Aloha, Oregon, USA) flow velocity at the right carotid and femoral arteries and a simultaneous ECG.[21]

2.4. Arterial wave reflections

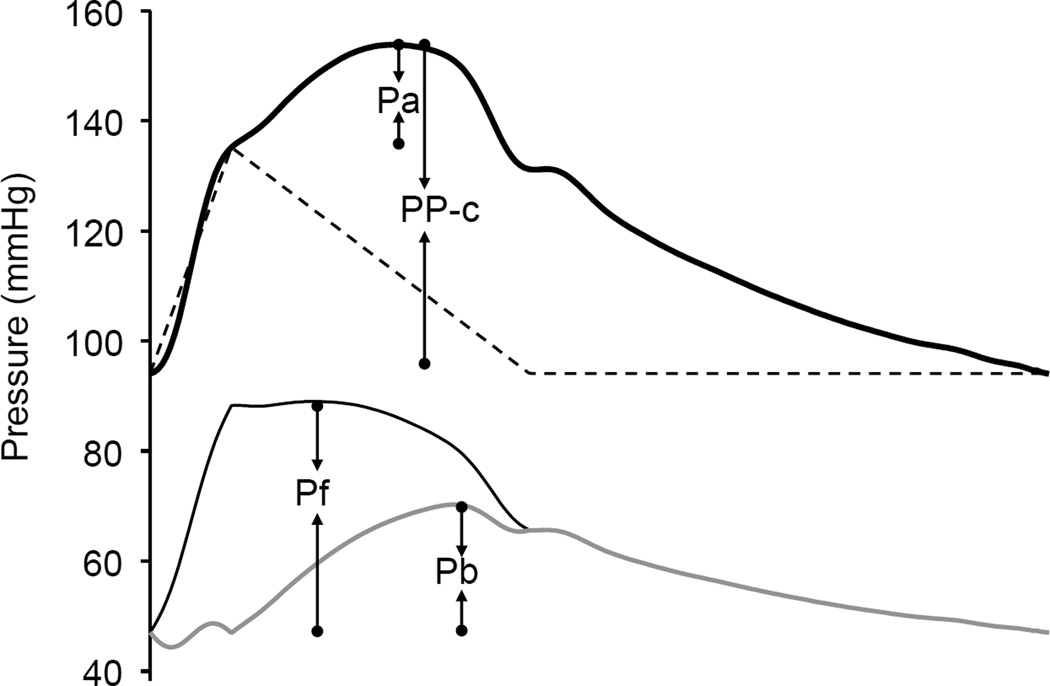

The calibrated carotid pressure waveform was analyzed to identify the inflection point resulting from the wave reflection using the zero-crossing timings of the fourth derivative of the pressure wave. [22] The augmented pressure (Pa) was the pressure amplitude above the inflection point, and the augmentation index (AI) was calculated as Pa divided by PP-c (Figure 1). The carotid pressure waveform was also separated into its forward and reflected components to calculate the transit time-independent parameter of wave reflection intensity using the validated triangulation method. [22, 23] This method creates a triangular-shaped flow wave by matching the onset, peak, and end of the flow wave to the timings of the foot, inflection point, and incisura of the carotid pressure wave (Figure 1). Because the calculation of both the forward and backward pressure components involves the product of flow and characteristic impedance (Zc), which itself has flow in the denominator, calibration of the flow waveform is not needed. Thus, the forward and backward components of the pressure wave can be constructed using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Pm(t) is the carotid pressure wave, F(t) is the approximated triangular-shaped flow wave, Pf(t) is the forward pressure component, and Pb(t) is the backward pressure component. Pf and Pb are the amplitudes of Pf(t) and Pb(t), respectively, with the latter being a transit-time independent index of wave reflections (Figure 1).[22, 24]

Figure 1.

Illustrations of augmented pressure (Pa), amplitude of backward pressure wave (Pb amplitude of forward pressure wave (Pf ), and carotid pulse pressure (PP-c). Pa and PP-c are derived from the calibrated carotid pressure waveform (thick solid line). Pb and Pf are derived from the forward (dark solid line) and backward (gray solid line) components decomposed from the carotid pressure waveform using a triangular flow wave (dashed line).

2.5. Biochemical variables

Overnight fasting serum and plasma samples were drawn for uric acid, C-peptide, and other biochemical measurements. Serum uric acid, cholesterol, triglycerides, and creatinine were measured with a Hitachi autoanalyzer 736–60 (Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) was measured using a precipitation method (Kodak Ektachem HDL Kit; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, New York, USA). Serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was calculated from the Friederwald formula. Plasma glucose concentration was determined by a hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method [Glucose (HK) Reagent Kit; Gilford Systems, Oberlin, Ohio, USA]. Fasting serum C-peptide was measured by radioimmunoassay (GP serum M1221, Novo, Bagaswaerd, Denmark).[25] We also calculated homeostasis model assessment estimated by C-peptide (HOMA-CP) for insulin resistance index.[26]

3. Statistical analysis

Differences of the basic characteristics between genders were examined with independent t test. Pearson’s correlation coefficients of uric acid and SBP-c with other variables were calculated. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed for cf-PWV, CO, TPR, Pb, AI, Pa, and SBP-c, respectively, as dependent variable and with uric acid and other confounders as independent variables. Additional path analysis was performed to test the fit of the correlation matrix against several causal models incorporating the complex relationships between the independent variable (uric acid, cf-PWV, Pb) and the dependent variable (SBP-c). All statistical procedures were carried out using the SAS statistical package 8.0 with statistical significance set at p<0.05. The Path analysis was conducted using the SAS CALIS procedure. The maximum likelihood method was used for parameter estimation on the variance-covariance matrix.

4. Results

4.1. Basic characteristics of study subjects with hemodynamic parameters

There are total 1303 subjects including 647 hypertensive and 656 normotensive subjects. Characteristics of the study population stratified by hypertension status and gender are shown in Table 1. In both normotensive and hypertensive groups, females have lower serum uric acid, weight, height, waist circumference, DBP-b, triglycerides, and creatinine, and higher HDL than males. No significant differences between females and males were observed for heart rate, C-peptide, and HOMA-CP. For the hemodynamic parameters, females had higher Pb, AI, Pa, TPR, males had higher CO, and females and males had similar cf-PWV, in both normotensive and hypertensive subjects.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics stratified by hypertension status and gender

| Variable | Normotensives | P value | Hypertensives | P value | All | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 656 |

N = 647 |

N = 1303 | |||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||

| n=295 | n=361 | n=300 | n=347 | ||||

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.0±1.2 | 6.5±1.5 | <0.001 | 5.9±1.6 | 7.0±1.7 | <0.001 | 6.1±1.7 |

| Age, years | 48.4±12.4 | 50.8±13.3 | 0.015 | 55.8±11.9 | 54.2±12.2 | 0.084 | 52.3±12.8 |

| Weight, Kg | 56.3±8.4 | 63.8±9.8 | <0.001 | 62.1±10.5 | 68.0±10.9 | <0.001 | 62.8±10.8 |

| Height, cm | 153.8±5.8 | 164.7±6.9 | <0.001 | 152.6±6.0 | 164.6±6.7 | <0.001 | 159.3±8.6 |

| Waist, cm | 79.0±7.7 | 84.4±7.5 | <0.001 | 86.1±9.3 | 89.6±8.1 | <0.001 | 85.0±9.0 |

| BMI | 23.8±3.3 | 23.5±2.8 | 0.162 | 26.6±4.1 | 25.0±3.3 | <0.001 | 24.7±3.6 |

| HR, bpm | 72.9±10.8 | 72.4±10.6 | 0.585 | 74.3±10.0 | 73.8±12.2 | 0.542 | 73.3±10.9 |

| SBP-b, mmHg | 116.3±11.5 | 117.9±10.5 | 0.063 | 159.8±19.7 | 151.2±17.3 | <0.001 | 136.4±24.6 |

| DBP-b, mmHg | 73.2±8.1 | 74.5±8.2 | 0.045 | 92.9±11.9 | 94.7±11.0 | 0.044 | 84.0±14.1 |

| PP-b, mmHg | 43.1±9.8 | 43.4±9.2 | 0.673 | 66.8±18.3 | 56.5±16.6 | <0.001 | 52.4±17.1 |

| SBP-c, mmHg | 107.8±11.2 | 109.6±10.0 | 0.034 | 149.4±19.1 | 142.3±17.4 | <0.001 | 127.4±23.9 |

| DBP-c, mmhg | 74.8±8.1 | 76.3±8.2 | 0.019 | 95.5±11.7 | 97.0±10.8 | 0.071 | 86.1±14.3 |

| PP-c, mmHg | 33.0±8.8 | 33.3±8.0 | 0.699 | 54.0±17.0 | 45.2±15.9 | <0.001 | 41.3±15.7 |

| Cho, mg/dL | 194.9±37.7 | 192.0±37.7 | 0.327 | 204.7±37.2 | 198.5±36.9 | 0.032 | 197.4±37.6 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 56.0±13.5 | 49.6±14.6 | <0.001 | 49.7±12.5 | 45.9±12.9 | <0.001 | 50.1±13.9 |

| TG, mg/dL | 95.1±60.9 | 120.5±92.7 | <0.001 | 134.2±86.9 | 153.3±126.4 | 0.026 | 126.7±98.2 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 119.1±35.6 | 116.5±37.7 | 0.373 | 126.7±36.4 | 118.3±40.1 | 0.005 | 120.0±37.7 |

| FBS, mg/dL | 96.7±11.2 | 95.1±13.9 | 0.100 | 106.6±34.9 | 101.9±21.4 | 0.034 | 100.0±22.5 |

| C-peptide, nM/L | 0.45±0.22 | 0.45±0.24 | 0.984 | 0.58±0.28 | 0.57±0.32 | 0.982 | 0.51±0.28 |

| HOMA-CP | 2.4±0.4 | 2.4±0.6 | 0.951 | 2.7±0.8 | 2.7±1.0 | 0.592 | 2.54±0.73 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.8±0.5 | 1.0±0.2 | <0.001 | 0.8±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 | <0.001 | 0.9±0.4 |

| cf-PWV, m/sec | 12.3±5.3 | 12.5±5.1 | 0.539 | 16.1±6.1 | 15.4±6.1 | 0.148 | 14.1±0.59 |

| Pb, mmHg | 11.3±3.9 | 10.2±3.6 | <0.001 | 20.6±7.3 | 16.0±6.9 | <0.001 | 14.5±7.0 |

| AI (%) | 26.9±16.5 | 10.9±22.6 | <0.001 | 38.8±13.3 | 24.6±20.1 | <0.001 | 25.0±21.1 |

| Pa, mmHg | 8.0±5.6 | 3.3±6.7 | <0.001 | 19.1±10.3 | 10.6±10.0 | <0.001 | 10.1±10.2 |

| TPR, mmHg-min/L | 17.2±5.4 | 15.8±6.2 | 0.001 | 20.2±6.4 | 18.6±5.9 | 0.001 | 17.9±6.2 |

| CO, L/min | 5.4±1.6 | 6.1±1.6 | <0.001 | 6.1±1.6 | 6.5±1.7 | 0.005 | 6.1±1.7 |

AI: augmentation index; BMI = body mass index; cf-PWV = carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; Cho = total cholesterol; CO = cardiac output; Cr = creatinine; DBP-b = brachial diastolic blood pressure; DBP-c = central diastolic blood pressure; FBS = fasting blood sugar; HDL = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-CP= homeostasis model assessment estimated by C-peptide; HR = heart rate; LDL = low density lipoprotein cholesterol; Pa = augmented pressure; Pb = amplitude of the reflected pressure wave; Pf = amplitude of the forward pressure wave; PP-b = brachial pulse pressure; PP-c = central pulse pressure; SBP-b = brachial systolic blood pressure; SBP-c = central systolic blood pressure; TG = triglycerides; TPR=total peripheral resistance;

4.2. Correlations for uric acid and SBP-c: univariate analysis

In the whole population, serum uric acid significantly correlated with SBP-c (r= 0.253, P<0.001), cf-PWV (r= 0.091, P=0.001), Pb (r= 0.100, P<0.001), AI (r= −0.056, P=0.043), CO (r= 0.144, P<0.001), and HOMA-CP (r= 0.227, P<0.001); and SBP-c significantly correlated with cf-PWV (r= 0.360, P<0.001), Pb (r= 0.784, P<0.001), AI (r= 0.358, P<0.001), Pa (r= 0.627, P<0.001), CO (r= 0.195, P<0.001), TPR (r= 0.286, P<0.001), and HOMA-CP (r= 0.275, P<0.001). In the hypertensives, serum uric acid significantly correlated with SBP-c and HOMA-CP in men and women (Table 2). For the hemodynamic parameters, serum uric acid significantly correlated with cf-PWV and CO in men but significantly correlated with Pb and Pa in women. On the other hand, SBP-c significantly correlated with all hemodynamic parameters except CO in men. In the normotensives, correlations for uric acid and SBP-c were generally less significant than those in the hypertensives (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations of serum uric acid and central systolic blood pressure with hemodynamic and insulin resistance parameters

| Variable | Sex | Uric acid | SBP-c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | HT | NT | HT | ||

| Uric acid | Men | 1 | 1 | 0.153** | 0.148** |

| Women | 1 | 1 | 0.097 | 0.297** | |

| SBP-c | Men | 0.153** | 0.148** | 1 | 1 |

| Women | 0.097 | 0.297** | 1 | 1 | |

| cf-PWV | Men | 0.032 | 0.106* | 0.293** | 0.199** |

| Women | 0.024 | −0.012 | 0.279** | 0.187** | |

| Pb | Men | 0.052 | −0.001 | 0.414** | 0.783** |

| Women | 0.089 | 0.202** | 0.676** | 0.794** | |

| AI | Men | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.351** |

| Women | 0.040 | 0.082 | 0.279** | 0.331** | |

| Pa | Men | 0.033 | −0.016 | 0.089 | 0.611** |

| Women | 0.056 | 0.191** | 0.523** | 0.698** | |

| CO | Men | 0.017 | 0.128* | 0.109* | −0.020 |

| Women | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.168** | 0.142** | |

| TPR | Men | 0.011 | −0.063 | 0.169** | 0.287** |

| Women | 0.047 | 0.086 | 0.090 | 0.159** | |

| HOMA-CP | Men | 0.074 | 0.205** | 0.084 | 0.066 |

| Women | 0.165** | 0.337** | 0.207** | 0.217** | |

P<0.05,

P<0.01.

AI = carotid augmentation index; BMI = body mass index; cf-PWV = carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CO=cardiac output; HOMA-CP = homeostasis model assessment estimated by C-peptide; HT = hypertensives; NT = normotensives; Pa = augmented Pressure; Pb = amplitude of backward pressure wave; SBP-c = central systolic blood pressure; TPR= total peripheral resistance.

4.3 Associations of uric acid with hemodynamic parameters by hypertension status: multi-variate analysis

In the whole population, serum uric acid was significantly positively associated with cf-PWV, Pb, AI, Pa, TPR and CO with adjustment for age and sex (Table 3, Model 1). Uric acid was significantly associated with Pb, AI, Pa, TPR, but not cf-PWV with further adjustment for waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, and heart rate (Model 2). Uric acid remained significantly associated with Pb, AI, Pa and TPR with further adjustment for HOMA-CP (Model 3) and cf-PWV (Model 4). Similar associations were observed in the hypertensive subjects, except that uric acid was not significantly independently associated with AI or TPR (Models 1–4). In contrast, uric acid was not significantly independently associated with cf-PWV, Pb, AI, Pb, CO, or TPR in the normotensive subjects (Models 1–4).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for the associations of uric acid with cf-PWV, Pb, AI, Pa, CO, and TPR stratified by hypertension status

| Dependent variable |

All (n=1303) | Normotensives (n=656) |

Hypertensives (n=647) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized coefficient β |

P | Standardized coefficient β |

P | Standardized coefficient β |

P | |

| cf-PWV | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.087 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.771 | 0.050 | 0.218 |

| Model 2 | 0.019 | 0.508 | −0.019 | 0.648 | 0.004 | 0.917 |

| Model 3 | −0.025 | 0.374 | −0.051 | 0.212 | −0.031 | 0.457 |

| Pb | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.167 | <0.001 | 0.049 | 0.218 | 0.079 | 0.018 |

| Model 2 | 0.135 | <0.001 | 0.052 | 0.195 | 0.083 | 0.018 |

| Model 3 | 0.119 | <0.001 | 0.047 | 0.246 | 0.074 | 0.037 |

| Model 4 | 0.118 | <0.001 | 0.048 | 0.238 | 0.074 | 0.036 |

| AI | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.071 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.931 | 0.024 | 0.519 |

| Model 2 | 0.070 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.669 | 0.045 | 0.248 |

| Model 3 | 0.069 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.746 | 0.054 | 0.170 |

| Model 4 | 0.068 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.757 | 0.054 | 0.167 |

| Pa | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.136 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.560 | 0.065 | 0.060 |

| Model 2 | 0.114 | <0.001 | 0.031 | 0.428 | 0.075 | 0.039 |

| Model 3 | 0.107 | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.515 | 0.076 | 0.037 |

| Model 4 | 0.106 | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.500 | 0.077 | 0.037 |

| CO | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.098 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.846 | 0.096 | 0.020 |

| Model 2 | 0.016 | 0.554 | −0.015 | 0.709 | 0.029 | 0.452 |

| Model 3 | 0.018 | 0.513 | −0.013 | 0.757 | 0.027 | 0.496 |

| TPR | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.070 | 0.019 | 0.030 | 0.505 | 0.007 | 0.869 |

| Model 2 | 0.086 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 0.427 | 0.050 | 0.243 |

| Model 3 | 0.077 | 0.015 | 0.030 | 0.501 | 0.051 | 0.236 |

| Model 4 | 0.076 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.494 | 0.052 | 0.232 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex;

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking and heart rate;

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, and HOMA-CP;

Model 4: adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, HOMA-CP, cf-PWV.

AI = carotid augmentation index; cf-PWV = carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CO= cardiac output; Pa = augmented Pressure; Pb = amplitude of backward pressure wave; TPR=total peripheral resistance.

4.4. Associations of uric acid with hemodynamic parameters in men and women: multi-variate analysis

Serum uric acid was significantly independently associated with Pb but not cf-PWV and CO in both men and women after accounting for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, and HOMA-CP (Table 4, Model 3). Uric acid remained significantly independently associated with Pb in men and women after further adjustment for cf-PWV (Table 4, Model 4). In men but not in women, uric acid was significantly independently associated with cf-PWV after accounting for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, and heart rate (Table 4, Model 2). In contrast, in women but not in men, uric acid was significantly positively associated with AI, Pa, and TPR after accounting for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, HOMA-CP, and cf-PWV (Table 4, Model 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for the associations of uric acid with cf-PWV, CO, TPR, Pb, AI, and Pa stratified by gender

| Men (n=708) | Women (n=595) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Standardized coefficient β |

P | Standardized coefficient β |

P |

| cf-PWV | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.126 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.988 |

| Model 2 | 0.080 | 0.035 | −0.067 | 0.071 |

| Model 3 | 0.070 | 0.065 | −0.079 | 0.067 |

| Pb | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.117 | <0.001 | 0.189 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 0.099 | 0.004 | 0.149 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 0.082 | 0.018 | 0.134 | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.144 | <0.001 |

| AI | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.096 | 0.017 |

| Model 2 | 0.071 | 0.057 | 0.081 | 0.046 |

| Model 3 | 0.067 | 0.078 | 0.087 | 0.037 |

| Model 4 | 0.063 | 0.096 | 0.096 | 0.020 |

| Pa | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.090 | 0.008 | 0.183 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 0.082 | 0.022 | 0.146 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 0.073 | 0.044 | 0.140 | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | 0.067 | 0.065 | 0.151 | <0.001 |

| CO | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.103 | 0.007 | 0.071 | 0.090 |

| Model 2 | 0.047 | 0.177 | −0.019 | 0.621 |

| Model 3 | 0.049 | 0.165 | −0.018 | 0.660 |

| TPR | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.016 | 0.672 | 0.121 | 0.004 |

| Model 2 | 0.008 | 0.844 | 0.152 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | −0.001 | 0.971 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | −0.006 | 0.890 | 0.158 | <0.001 |

Model 1: adjusted for age; Model 2: adjusted for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking and heart rate; Model 3: adjusted for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, and HOMA-CP; Model 4: adjusted for age, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking, heart rate, HOMA-CP, and cf-PWV.

CO= cardiac output; TPR=total peripheral resistance; AI = carotid augmentation index; cf-PWV = carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; Pa = augmented Pressure; Pb = amplitude of backward pressure wave.

4.5. Independent determinants of SBP-c

Multivariate regression models with SBP-c as the dependent variable are shown in Table 5. In the whole population, uric acid, cf-PWV, HOMA-CP, CO, and TPR were significant independent determinants of SBP-c with a model r2 of 0.566 after adjustment for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking and heart rate (Table 5, Model A). These independent associations remained after including AI in the model (Model B, r2 = 0.597). Serum uric acid remained significantly associated with SBP-c when Pb instead of AI was included the model (Model C, r2 = 0.839). Pb (partial r2 = 0.651), CO (partial r2 = 0.062), TPR (partial r2 = 0.021), and cf-PWV (partial r2 = 0.005) explained (partial r2/Model r2) 77.5%, 7.4%, 2.5%, and 0.5% of total variance of SBP-c, respectively.

Table 5.

Independent contributions of uric acid and the steady and pulsatile hemodynamic variables to central systolic blood pressure

| Model A Total R2=0.566 |

Model B Total R2=0.597 |

Model C Total R2=0.839 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Standard β | R2 | Standard β | R2 | Standard β | R2 |

| variables | ||||||

| Uric acid | 0.119** | 0.006 | 0.099** | 0.010 | 0.065** | 0.005 |

| cf-PWV | 0.149** | 0.125 | 0.141** | 0.020 | 0.092** | 0.005 |

| HOMA-CP | 0.067* | 0.004 | 0.074** | 0.004 | NS | NS |

| CO | 0.777** | 0.287 | 0.738** | 0.220 | 0.436** | 0.062 |

| TPR | 0.814** | 0.076 | 0.762** | 0.061 | 0.463** | 0.021 |

| AI | - | - | 0.229** | 0.146 | - | - |

| Pb | - | - | - | - | 0.718** | 0.651 |

: p<0.05,

p<0.001, NS = non-significant.

Model A: adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, body mass index, creatinine, total cholesterol, smoking and heart rate;

Model B: further adjusted for AI;

Model C: further adjusted for Pb instead of AI.

AI = carotid augmentation index; cf-PWV = carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CO=cardiac output; HOMA-CP= homeostasis model assessment estimated by C-peptide; Pb = amplitude of backward pressure wave; TPR=total peripheral resistance.

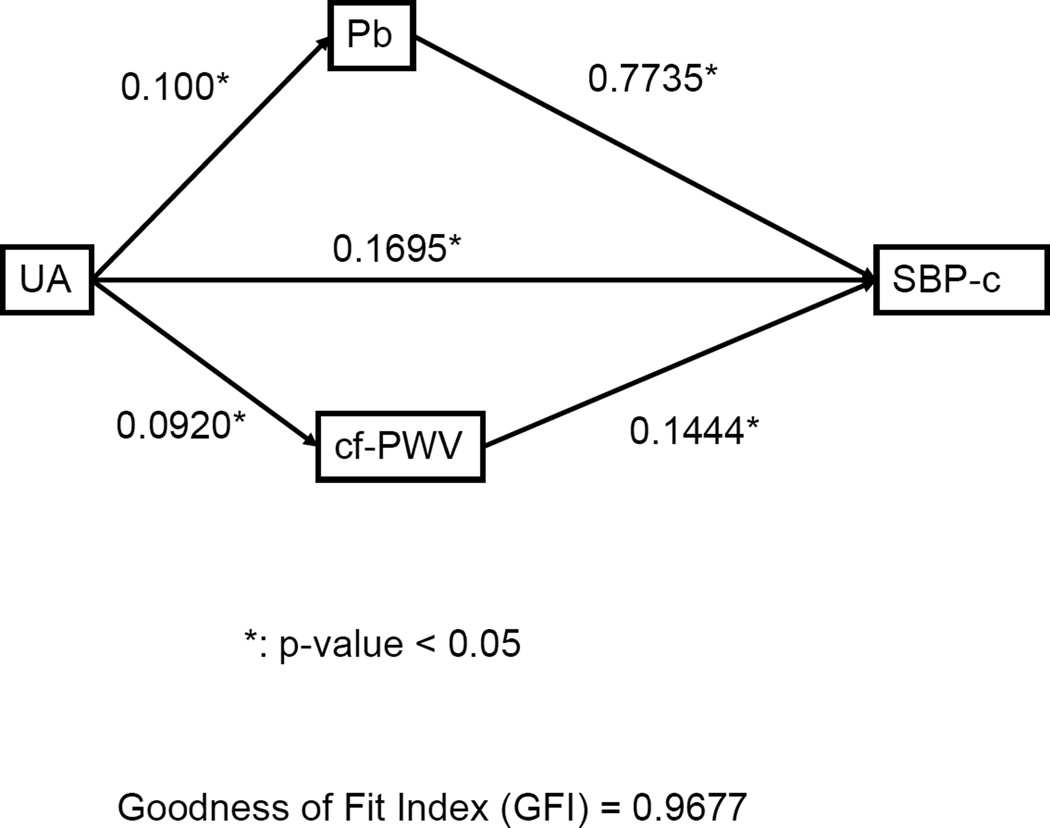

4.6. Potential pathways between uric acid and SBP-c

Using the Path analysis, the best causal model with uric acid, cf-PWV, and Pb as independent variables and SBP-c as the dependent variable is shown in Figure 2. According to the model, uric acid may cause high SBP-c by directly increasing wave reflections and arterial stiffness. In addition, uric acid may also directly cause high SBP-c independently of the hemodynamic determinants.

Figure 2.

Path analysis for the hypothetical causal relationships among serum uric acid, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cf-PWV), amplitude of backward pressure wave (Pb), and central systolic blood pressure (SBP-c). A single-headed arrow points from cause to effect. Numbers along the causal paths are path coefficients (standardized regression coefficients) indicating the direct effect of a variable assumed to be a cause on another variable assumed to be an effect.

5. Discussion

In this cohort of 1303 community-based normotensive and untreated hypertensive subjects, major independent hemodynamic determinants of SBP-c were Pb, CO, TPR, and cf-PWV, in order of importance. Serum uric acid significantly correlated with Pb and cf-PWV in men, and Pb and TPR in women. Uric acid was significantly associated with Pb independently of cf-PWV in both men and women. Uric acid was also significantly associated with SBP-c independently of the major hemodynamic parameters. Therefore, uric acid may cause hypertension mainly through increased wave reflections and other non-hemodynamic mechanisms.

Uric acid, arterial wave reflections and total peripheral resistance

The major novel finding of the present study was the significantly independent positive correlation between uric acid and intensity of arterial wave reflection as assessed by Pb, in men and women in multi-variate analysis. Furthermore, this association was observed in the hypertensive but not normotensive subjects. Similar but less significant positive associations were also observed for AI and Pa. The generally consistent results strongly support the independent association between serum uric acid level and wave reflection intensity. Besides, there also existed significant correlations between uric acid and TPR in our study subjects especially in women.

Hyperuricemia may be a marker or a cause of endothelial dysfunction, because impaired endothelial function as assessed by measuring the flow-mediated vasodilation has been demonstrated in hyperuricemic patients.[3, 27] Endothelial dysfunction is associated with increased arterial wave reflection, and AI has been used to assess endothelial function.[28] Thus, hyperuricemia may increase wave reflection intensity through the mediation of endothelial dysfunction.[29]

In the never-treated hypertensive women, it has been shown that uric acid was negatively associated with AI.[14] Because AI depends heavily on the reflected wave transit time and gender,[22] the true impact of uric acid on wave reflection may have been underestimated or obscured in the study.[14]

Our result of the correlation between uric acid and TPR in women was compatible with recent 2 studies. Three hundred and thirty eight hypertensive subjects were evaluated for serum uric acid and some hemodynamic parameters from the common carotid ultrasound analysis. Serum uric acid correlated with internal carotid artery resistive index (ICRI, a hemodynamic measure that reflects local vascular impedance and microangiopathy) in women (r = 0.34, p<0.001) but not in men.[30] In another prehypertensive obese aldolescents study, urate-lowering therapy lowered blood pressure and reduced TPR.[10]

Uric acid and arterial stiffness

In the present study, uric acid appeared to correlate with cf-PWV only in hypertensive men but not in women. The observed gender difference was in accord with the results from another study involving 940 Chinese workers and their family members.[16] In that study serum uric acid collected during cardiovascular health examinations was significantly and positively associated with cf-PWV in men but not in women, after adjustment for covariates.[16] Although several studies showed significant positive correlation between serum uric acid and arterial stiffness [14, 15, 17, 18], negative correlation has also been reported.[19, 31] In 1276 Koreans who underwent a health check-up, uric acid was not significantly associated with heart-femoral or brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in men or women.[31] In 292 subjects with never-treated stage I-II essential hypertension subjects, serum uric acid levels were independently associated with hs-CRP and adiponectin levels but not with c-f PWV in essential hypertensive patients.[19] Thus, the relationship between serum uric acid levels and arterial stiffness appears to be inconsistent and may depend on ethnicity, gender, and other confounders such as insulin resistance, hypertension status and use of medications. It is likely that arterial stiffness may play a minor role in the uric acid-blood pressure relationship. In contrast, insulin resistance and/or metabolic syndrome have been consistently associated with increased arterial stiffness in various ethnicities and in both genders. [32–35]

Uric acid and central blood pressure

The present study confirms that uric acid is independently associated with SBP-c, especially in the hypertensive subjects.[16] More importantly, our results may provide potential pathophysiologic insights into the causal relationships between uric acid and SBP-c. The strength of the relationship between serum uric acid and hypertension may decrease with increasing age and duration of hypertension disease,[3] suggesting the potential role of uric acid in the young hypertensives. Furthermore, lowering uric acid with allopurinol in hyperuricemic adolescents with newly diagnosed hypertension or prehypertensive has been shown to lower blood pressure. [9, 10] Because wave reflection dominates age-related changes in central blood pressure throughout the human lifespan, [13, 22] the independent association of uric acid with Pb, AI, and Pa may suggest the importance of uric acid in the development of hypertension in both young and elderly subjects. Indeed, in the present study, the association of uric acid and Pb was significant in the young (<50 years old) and old (≥50 years old) subjects and both uric acid and Pb were significant independent determinants of SBP-c in the young and old subjects (data not shown). It is also important to recognize that uric acid may directly cause increased SBP-c independently of wave reflection and arterial stiffness. A recent review summarized the results from animal studies and clinical observations and indicated that renal microvascular and tubulointerstitial injury may be the key to uric acid-induced hypertension.[3] Our results support that other mechanisms, such as endothelial dysfunction, low-level systemic inflammation, and sympathetic overactivity, may also render uric acid a direct role in the pathogenesis of hypertension.[3]

Gender difference of uric acid in the association with hemodynamic parameters

Gender differences in uric acid related adverse cardiovascular prognosis have been observed. The post-hoc analysis from The Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension trial demonstrated that the association between the level of serum uric acid and cardiovascular outcomes was significant only in women after adjustment for the Framingham risk score.[36] Additionally, serum uric acid was found to be independently associated with silent brain infarcts in women, but not in men.[37] Furthermore, serum uric acid was shown to correlate to renal resistive index only in women,[38] strengthening the assumption that female gender exhibits higher selectivity for uric acid induced microvascular damage. The explanation for such gender differences is not clear, but may be related to variation in sexual hormone profile. Our findings of differential associations of uric acid with hemodynamic parameters further support a special role for serum uric acid in cardiovascular hemodynamics and outcomes, especially in women.

Limitations

We used C-peptide to replace insulin in homeostasis model assessment to evaluate insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), due to lack of insulin data. It has been shown that HOMA-CP and HOMA-IR were highly correlated and both produced similar assessment of insulin resistance.[26] Our study did not include target organ damage index such as carotid intima-media thickness, microalbuminuria, and systemic inflammation markers, which may be helpful for further mechanistic investigations. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study and further longitudinal studies are needed to establish the possible cause-effect relationships between serum uric acid, insulin resistance, and vascular parameters. Although our conclusions may be speculative, they are not unrealistic since the role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of hypertension has been well supported by longitudinal studies [1–3] and increased arterial stiffness and/or wave reflection are recognized mechanisms of the development of hypertension.[39, 40]

Conclusions

In a population of normotensive and untreated hypertensive Taiwanese participants without apparent cardiovascular diseases, uric acid was independently associated with wave reflections in both men and women. Furthermore, uric acid was significantly associated with central blood pressure independently of wave reflections and arterial stiffness, especially in the hypertensive subjects. Therefore, there may be multiple possible pathways in which uric acid is involved in causing hypertension. Future confirmatory studies may lead to the development of new therapeutic targets for treating hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 99-2314-B-010 -034 -MY3) and intramural grants (V97C1-101, V98C1-028, and V99C1-091) from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan, Republic of China, and was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

References

- 1.Alper AB, Jr, Chen W, Yau L, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Hamm LL. Childhood uric acid predicts adult blood pressure: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;45:34–38. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150783.79172.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzali M, Kanbay M, Segal MS, Shafiu M, Jalal D, Feig DI, et al. Uric acid and hypertension: cause or effect? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:108–117. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwu CM, Lin KH. Uric acid and the development of hypertension. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:RA224–RA30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viazzi F, Parodi D, Leoncini G, Parodi A, Falqui V, Ratto E, et al. Serum uric acid and target organ damage in primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:991–996. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000161184.10873.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu YQ, Li J, Xu YX, Wang YL, Luo YY, Hu DY, et al. Predictive value of serum uric acid on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in urban Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1387–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meisinger C, Koenig W, Baumert J, Doring A. Uric acid levels are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality independent of systemic inflammation in men from the general population: the MONICA/KORA cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1186–1192. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strasak A, Ruttmann E, Brant L, Kelleher C, Klenk J, Concin H, et al. Serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular mortality: a prospective long-term study of 83,683 Austrian men. Clin Chem. 2008;54:273–284. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:924–932. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soletsky B, Feig DI. Uric Acid reduction rectifies prehypertension in obese adolescents. Hypertension. 2012;60:1148–1156. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.196980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C. McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretical, Experimental and Clinical Principles 6th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng HM, Wang KL, Chen YH, Lin SJ, Chen LC, Sung SH, et al. Estimation of central systolic blood pressure using an oscillometric blood pressure monitor. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:592–599. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namasivayam M, McDonnell BJ, McEniery CM, O’Rourke MF. Does wave reflection dominate age-related change in aortic blood pressure across the human life span? Hypertension. 2009;53:979–985. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Vyssoulis G, Bratsas A, Baou K, Tzamou V, et al. Association of serum uric acid level with aortic stiffness and arterial wave reflections in newly diagnosed, never-treated hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:33–39. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo CF, Yu KH, Luo SF, Ko YS, Wen MS, Lin YS, et al. Role of uric acid in the link between arterial stiffness and cardiac hypertrophy: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology(Oxford) 2010;49:1189–1196. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Li Y, Sheng CS, Huang QF, Zheng Y, Wang JG. Association of serum uric acid with aortic stiffness and pressure in a Chinese workplace setting. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:387–392. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Toda E, Hashimoto H, Nagai R, Yamakado M. Higher serum uric acid is associated with increased arterial stiffness in Japanese individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai WC, Huang YY, Lin CC, Li WT, Lee CH, Chen JY, et al. Uric acid is an independent predictor of arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients. Heart Vessels. 2009;24:371–375. doi: 10.1007/s00380-008-1127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsioufis C, Kyvelou S, Dimitriadis K, Syrseloudis D, Sideris S, Skiadas I, et al. The diverse associations of uric acid with low-grade inflammation, adiponectin and arterial stiffness in never-treated hypertensives. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:554–559. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Spurgeon HA, Ting CT, Lakatta EG, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27:461–467. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283220ea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CH, Ting CT, Lin SJ, Hsu TL, Ho SJ, Chou P, et al. Which arterial and cardiac parameters best predict left ventricular mass? Circulation. 1998;98:422–428. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang KL, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Chuang SY, Li CH, Spurgeon HA, et al. Wave reflection and arterial stiffness in the prediction of 15-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities: a community-based study. Hypertension. 2010;55:799–805. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerhof BE, Guelen I, Westerhof N, Karemaker JM, Avolio A. Quantification of wave reflection in the human aorta from pressure alone: a proof of principle. Hypertension. 2006;48:595–601. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238330.08894.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao CF, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Yu WC, Chen CH. Determinants of pressure wave reflection: characterization by the transit-time independent reflected wave amplitude. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:665–671. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CH, Tsai ST, Chuang JH, Chang MS, Wang SP, Chou P. Population-based study of insulin, C-peptide, and blood pressure in Chinese with normal glucose tolerance. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:585–588. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Zhou ZG, Qi HY, Chen XY, Huang G. [Replacement of insulin by fasting C-peptide in modified homeostasis model assessment to evaluate insulin resistance and islet beta cell function] Zhong nan da xue xue bao Yi xue ban. 2004;29:419–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho WJ, Tsai WP, Yu KH, Tsay PK, Wang CL, Hsu TS, et al. Association between endothelial dysfunction and hyperuricaemia. Rheumatology(Oxford) 2010;49:1929–1934. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber T, Maas R, Auer J, Lamm G, Lassnig E, Rammer M, et al. Arterial wave reflections and determinants of endothelial function a hypothesis based on peripheral mode of action. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Lozada LG, Nakagawa T, Kang DH, Feig DI, Franco M, Johnson RJ, et al. Hormonal and cytokine effects of uric acid. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:30–33. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000199010.33929.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipolli JA, Ferreira-Sae MC, Martins RP, Pio-Magalhaes JA, Bellinazzi VR, Matos-Souza JR, et al. Relationship between serum uric acid and internal carotid resistive index in hypertensive women: a cross-sectional study. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2012;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim JH, Kim YK, Kim YS, Na SH, Rhee MY, Lee MM. Relationship between serum uric Acid levels, metabolic syndrome, and arterial stiffness in korean. Korean Circ J. 2010;40:314–320. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2010.40.7.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho CT, Lin CC, Hsu HS, Liu CS, Davidson LE, Li TC, et al. Arterial stiffness is strongly associated with insulin resistance in Chinese--a population-based study (Taichung Community Health Study, TCHS) J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:122–130. doi: 10.5551/jat.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganne S, Winer N. Vascular compliance in the cardiometabolic syndrome. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2008;3:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4572.2008.05630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Orru M, Usala G, Piras MG, Ferrucci L, et al. The central arterial burden of the metabolic syndrome is similar in men and women: the SardiNIA Study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:602–613. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Muller DC, Andres R, Hougaku H, Metter EJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoieggen A, Alderman MH, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Devereux RB, De Faire U, et al. The impact of serum uric acid on cardiovascular outcomes in the LIFE study. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heo SH, Lee SH. High levels of serum uric acid are associated with silent brain infarction. J Neurol Sci. 2010;297:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viazzi F, Leoncini G, Ratto E, Falqui V, Parodi A, Conti N, et al. Mild hyperuricemia and subclinical renal damage in untreated primary hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. Recent advances in arterial stiffness and wave reflection in human hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1202–1206. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghiadoni L, Bruno RM, Stea F, Virdis A, Taddei S. Central blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and wave reflection: new targets of treatment in essential hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2009;11:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]