Abstract

Background

Service user (patient) involvement in care planning is a principle enshrined by mental health policy yet often attracts criticism from patients and carers in practice.

Aims

To examine how user-involved care planning is operationalised within mental health services and to establish where, how and why challenges to service user involvement occur.

Method

Systematic evidence synthesis.

Results

Synthesis of data from 117 studies suggests that service user involvement fails because the patients' frame of reference diverges from that of providers. Service users and carers attributed highest value to the relational aspects of care planning. Health professionals inconsistently acknowledged the quality of the care planning process, tending instead to define service user involvement in terms of quantifiable service-led outcomes.

Conclusions

Service user-involved care planning is typically operationalised as a series of practice-based activities compliant with auditor standards. Meaningful involvement demands new patient-centred definitions of care planning quality. New organisational initiatives should validate time spent with service users and display more tangible and flexible commitments to meeting their needs.

Enabling service user involvement in care planning is a principle enshrined by contemporary mental health policy and guidelines,1–3 and a potentially effective method of improving the culture and responsiveness of mental health services in the UK. Systematic synthesis of small-scale studies suggests that initiatives aimed at enhancing user-involved care planning can enhance service development, improve staff attitudes and increase service user esteem.4 Yet despite the consistency of the political rhetoric, the majority of service users and carers continue to feel marginalised in the planning of their care. Nationally commissioned surveys in the UK report high levels of dissatisfaction with service user and carer involvement across in-patient and community settings.5,6 A systematic review of UK mental health nursing revealed that service users and carers consistently request greater information provision, more meaningful treatment choices and increased involvement in care consultations; the stability of these responses over time suggests a sustained lack of policy impact on clinical practice.7 Synthesis suggests that previous models of involvement may not have been as effective as first envisaged.

The reasons underpinning a sustained lack of policy influence on practice are unclear. The Francis inquiry into failings in National Health Service (NHS) provision has highlighted the potential for organisational and governance deficiencies to negatively affect patient-centred care.8 Yet it is also acknowledged that mental health services differ from physical health services in a number of discrete ways. Distinguishing features include a unique service history founded on aspects of containment and compulsion, the need for care teams to accommodate a greater multiplicity of service user experiences and the entrenched stigmatisation of those using mental health services.9

To date, no systematic exploration of the failure to translate user-involved care planning into practice has occurred. We sought to address this evidence gap through a systematic synthesis of the barriers and facilitators to service user involvement in care planning in secondary mental healthcare. The primary aim was to examine how service user involvement is typically operationalised within mental health services and to establish where, how and why key challenges to such involvement occur.

Method

This review examined the way in which service user involvement is operationalised within secondary mental health services compared with the theoretical principles upheld by contemporary mental health policy. Its scope was international, examining service user involvement in care planning across different organisational and secondary care settings. The review was individually focused in that it examined service users' involvement in their own care. It did not extend to service user or carer involvement in service design or delivery.

Search strategy

The review began with a broad search strategy to develop a theoretical frame of reference for evidence synthesis. A scoping search of published literature was initially undertaken to identify key theoretical and conceptual papers delineating the different philosophies underpinning or driving patient-involved care planning. Search terms were developed from key facets of the research question, namely care planning, mental health and user participation (see online Appendix DS1). Search terms were identified by research team discussion, MeSH browsing, scanning of the background literature and consultation with mental health professionals (psychiatrists and mental health nurses) serving on the project's advisory panel. Search terms were subsequently combined within each concept with the Boolean operator ‘OR’ and across all concepts with ‘AND’.

Searches were undertaken on Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EMBASE, HMIC, British Nursing Index, Dissertation Abstracts (accessed via Ovid SP), CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE (accessed via the Cochrane Library), ISI Web of Science including SSCI and SCIEXPANDED (accessed via Web of Knowledge), ASSIA, IBSS and Social Services Abstracts (accessed via Proquest). Key psychiatry, medical and nursing journals were also hand-searched for the period 2010–2011: Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, BMJ, British Journal of Psychiatry, General Hospital Psychiatry, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, International Journal of Nursing Studies, Journal of Advanced Nursing and Psychiatric Bulletin. Grey literature including conference abstracts, policy documents and material generated by third sector or user-led enquiry was identified via the British National Bibliography for Report Literature, Google Scholar and the websites of relevant UK government departments and charities (e.g. the Department of Health, Rethink and Mind). Searches were limited to articles published in English from database inception to December 2012. An update search was performed in February 2014. Full copies of the search strategies used in the review are available from the authors.

All identified papers were screened by title, abstract and subject headings against pre-specified eligibility criteria, and full-text copies of potentially eligible studies were obtained. Inclusion criteria comprised any report or study providing primary data focused on care planning processes in secondary mental healthcare; eligible studies provided process data and/or reported potential barriers and facilitators to user-involved care planning, where care planning was defined as any interaction between a service user and health professional for the purposes of discussing or addressing that client's needs or treatment decisions. Studies focused solely on the outcomes of user involvement or user participation for the purposes of service design were excluded. Single-person perspectives were also excluded in an attempt to limit bias from potentially non-representative views. Two reviewers (P.B., O.P.) independently undertook study eligibility judgements, with discrepancies referred to a third member of the project team (K.L.).

Data synthesis

We adopted a deductive ‘line of argument’ approach to data synthesis, informed a priori by the development of a conceptual framework of service user involvement. Key policy reports and conceptual papers were identified and used to establish the core components and stages of the care planning process. Subsequent work sought to systematically confirm or refute the propositions inherent in this framework by narratively synthesising the empirical evidence. The authors O.P. and P.B. independently extracted data, with discordance resolved by discussion with K.L. and J.B. Evidence hierarchies for intervention implementation are not well developed. In the absence of any formal consensus we extracted data from all eligible randomised trials, non-randomised studies, and uncontrolled and qualitative designs. Key quality indicators were drawn from published guidelines.10–12 These considered aspects of study design, dimensions and characteristics of the study site, sample size, sampling methods and mode of data collection and analysis. No study was rejected on the basis of quality unless it was deemed impossible to understand. This inclusive approach was driven by a lack of empirically tested quality criteria for service user-led enquiry,13 and remains in accordance with other systematic syntheses involving patient views.14,15

Greater emphasis was placed on study contribution defined in terms of ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ data descriptions.16 ‘Thick’ descriptions comprised rich accounts of care planning procedures including an in-depth examination of the mechanisms by which service user involvement was challenged or encouraged. By definition, these studies employed rigorous data collection and analysis techniques and met minimum British Sociological Association criteria for the evaluation of qualitative research.17 ‘Thin’ data descriptions lacked detail and failed to discuss the reasons behind successful or failed service user involvement. Thin data descriptions were derived from quantitative research designs (e.g. controlled intervention studies or closed-question satisfaction surveys) and less rigorous qualitative approaches (e.g. open-ended enquiry lacking formal data analysis procedures). Data synthesis prioritised studies providing the ‘thickest’ descriptions of care planning procedures. Studies providing ‘thinner’ descriptions were used to augment and contextualise the findings.

A data synthesis tool enabled the consolidation of data across studies. Study characteristics and data contribution were tabulated and primary data were mapped to the relevant domains of the theoretical framework developed at the beginning of the review. Where present, verbatim quotations were extracted and indexed to capture the key themes and subthemes pertaining to service user involvement in care planning procedures. Narrative synthesis occurred within and across the framework domains. Synthesis was undertaken by P.B. and continually shared with the project team. For clarity, the development of our theoretical framework is presented prior to our synthesis of primary data.

Results

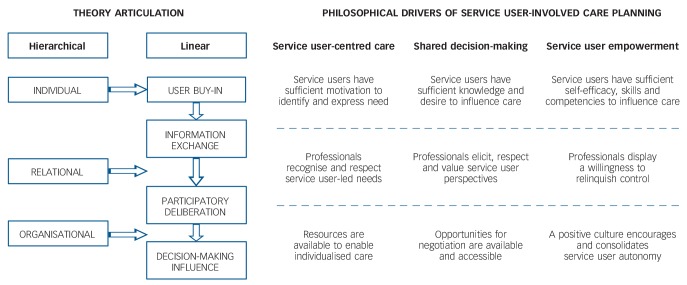

Initial scoping searches failed to identify any text that referenced an explicit historical driver for service user involvement in mental healthcare planning. Instead, the process was framed as a core component of three broader, contemporary care philosophies. These were patient-centred care (e.g. the study by Mead & Bower18), shared decision-making (e.g. Makoul & Clayman19) and patient empowerment (e.g. Hickey & Kipping20). Each philosophy exhibited some fluidity and overlap such that their comparison identified a common set of antecedents to successful service user involvement. These antecedents comprised adequate service user buy-in, meaningful information exchange, participatory deliberation and participatory decision-making.

We acknowledged a priori that the successful implementation of any care philosophy invariably depends upon the respective power of the agents and agencies involved. We thus introduced three levels of intervening variables to our framework: the capacities and competencies of individual service users; the extent and quality of their interactions with health professionals; and features of the organisational context in which care occurred. In this way, theory articulation allowed for the conceptualisation of user-involved care planning as both a linear (outcome-focused) and a hierarchical (process-focused) event (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework for evidence synthesis.

Synthesising primary evidence

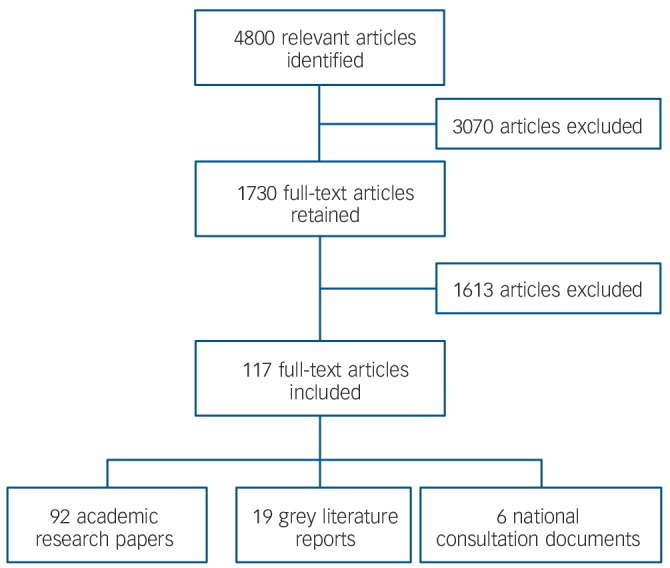

Systematic searches yielded 4800 articles excluding duplicates, of which 117 primary research studies were included in our review (Fig. 2). The 117 papers reported data collected from 13 countries, most frequently the UK (56 studies), USA (29 studies), Australia (9 studies) and Sweden (6 studies). Most of the eligible studies (92; 79%) were academic research papers. Nineteen (16%) were classified as grey literature comprising policy reports, voluntary organisation and user-led enquiry. Six (5%) were national consultation documents. In total 84 studies reported service users' views, 17 reported carers' views and 33 the views of mental health and allied health professionals. Seventy-nine studies were focused on community mental healthcare and 49 on in-patient care. Some studies reported on multiple groups, and therefore numbers exceed 100%.

Fig. 2.

Flow of studies through the review.

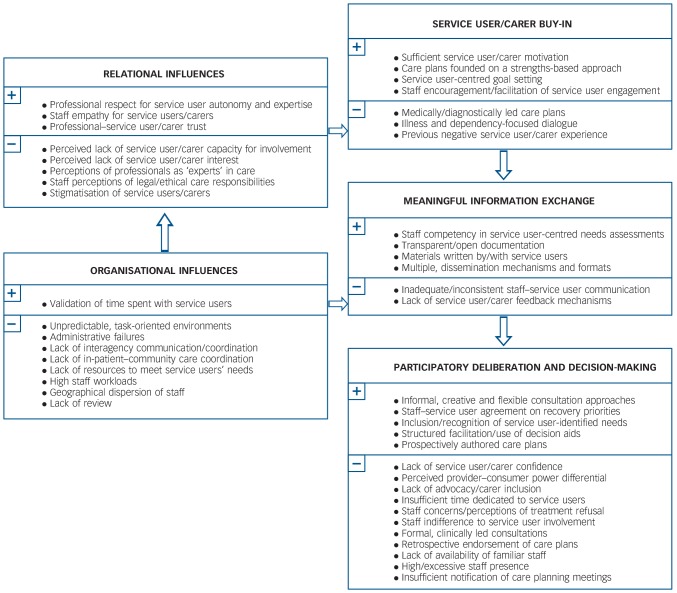

Thirty-seven studies provided ‘thick’ data descriptions. By definition, these studies were of either a qualitative or a mixed method design and generated their data through semi-structured or unstructured methods. Three of the 37 studies were conducted on behalf of national service user organisations,21–23 and two were explicit in including service users as active members of the research team.24,25 Consistent with the qualitative methods adopted, sample sizes were moderate to small (range 5–500, median 37). The majority of studies (29 studies, 78%) recruited participants across several study sites, although data remained biased towards the views of female and community-based service users. Key characteristics and findings of these studies are summarised in online Table DS1. Study context, sample characteristics and data contributions for studies providing ‘thinner’ descriptions are provided in online Table DS2. Joint evidence synthesis is described below and summarised in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Overview of care planning barriers (−) and facilitators (+).

Care planning as a linear event

A linear model of user-involved care planning presents a series of discrete, task-driven conditions, all of which must be met in order for the desired outcome to occur. The first step in any such model is establishing service users' motivation for involvement. Although negative bias in satisfaction surveys is acknowledged, quantitative evidence remains strikingly consistent in implying that the majority of service users are motivated to engage in care planning, and that they typically demand a greater level of involvement than is ordinarily achieved. National consultation and large-scale surveys conducted across both in-patient and community settings repeatedly highlight service user and carer requests for more meaningful participation in needs assessments, care consultations and treatment decisions.2,3,5,6,26–38 In-depth qualitative data suggest that the primary driver for this involvement is the desire of service users and carers to move away from traditional, paternalistic models of care towards more patient-centred approaches capable of prioritising and responding to individual need.21,24,25,32,39,40–42 Service user and carer discourses highlight a marked gap between policy and practice created by an overreliance on diagnostically led consultations,25,41,43,44 and a failure among mental health professionals to address multiple or dual-diagnostic needs.21,42,45 These observations are reflected in quantitative audit and survey research which, although biased towards in-patient settings, confirms a desire for (or lack of recognition of) patients' strengths,31,46,47 and potential neglect or misinterpretation of their physical, vocational, social and cultural needs.47–49

Triangulation of qualitative and quantitative evidence suggests that consultation processes that serve to accentuate perceptions of service user dependency may be most likely to challenge their motivation for involvement.25,31,32,37,41,45,47,48,50,51 Although limited in number, small-scale studies of advance directives additionally suggest that some service users may be reluctant to engage in illness-focused discussions for fear of engaging in discourse that might negatively influence their mental health.52–54 Rather, service users and carers express a preference for – and portray a greater readiness to participate in – strength-based approaches based on concepts of recovery and hope.21,24,25,32,42,46,55,56 These preferences are highlighted in rigorous qualitative studies and supported by correlational studies and surveys that report enhanced service user satisfaction and engagement with individualised care planning and case management models.52,55,57–63

Information provision and choice

Meaningful care planning involvement requires service users not only to be motivated to engage in participatory discussions but also to have the relevant knowledge and resources to do so. Irrespective of setting or publication date, small and larger-scale quantitative surveys have consistently reported gaps in service users' and carers' understanding of care planning procedures and their implementation within secondary mental healthcare.3,22,38,46,64–71 Although smaller in number, rigorous qualitative studies confirm that service users and carers lack staff and service feedback,21,41,42,72 and often receive insufficient information and support to contribute meaningfully to decisions about their care.21,41,42,51,72–77 Specific to carer discourse is the claim that patient confidentiality serves as an effective but potentially ill-used barrier between mental health professionals and themselves.78,79 From the patients' perspective key deficits have been identified in their illness understanding, knowledge of the medicolegal aspects of mental healthcare and their awareness and appreciation of medication choices and side-effects.21,79 Quantitative, survey and national consultation data corroborate these information gaps,27,31,33,38,64,66,68,80,81 additionally highlighting potential deficits in service users' and carers' knowledge of keyworker contacts,28,68,82,83 care planning documentation,64 and scheduled dates and processes pertaining to care planning reviews.27,48,64

The persistent failure to provide service users and carers with pharmacological information and choice emerges as one of the most common barriers to meaningful care planning involvement across both quantitative and qualitative research designs.27,28,31,33,38,66,79,84 Isolated data from one moderately sized survey conducted in a mixed clinical setting purport that individuals who receive such information are significantly more likely to be educated in why their medication has been prescribed than to be informed of their legal right to refuse.33 Although not directly corroborated by other studies, these data raise the possibility of a deficit not only in the capacity of mental health services to disseminate information, but also in the provision of potential opportunities for service users to exercise decision-making control. Although some empirical support for this hypothesis is available, rigorous data are sparse and biased towards in-patient settings.67,75,85

Potential for divergent opinion exists. Although both quantitative and qualitative data have suggested that service users do not routinely receive education about their legal rights,52,66,79–81 one national survey has revealed a belief among ward managers that this information is indeed provided.86 Accepting a minimum level of data quality across the studies, this contradiction implies one of two things: either that there is scope for temporal or geographical variation in practice, or that traditional methods of communication between service users and professionals have failed. Current evidence is not sufficiently developed to discriminate between the two. Qualitative and mixed method explorations suggest a need for care planning dialogue that can be more easily understood.87,88 National consultation also advocates greater transparency in information provision, with the shared recommendation that information is written by or with service users,81 and disseminated in a wider range of formats across multiple service settings.3,81

Participatory deliberation

The instigation of a collaboratively defined, mutually endorsed care plan demands not only that service users understand the questions and choices posed to them, but also that they appear sufficiently competent in communicating a response. Survey data collected from two moderately sized samples of users and carers have previously suggested that many lack confidence during care-planning consultations,89 and that some may express uncertainty regarding their own ability to contribute meaningfully to their care.89,90 Inductive qualitative analyses indicate that the predominant factor eroding service user and carer confidence may be a perceived power differential between themselves and mental health professionals.25,42,43,73,79,84,91 Less frequently, this perception is attributed to socially embedded constructs of health professionals as individuals holding superior positions within educational and socio-economic hierarchies.42 Much more commonly it is attributed to – and amplified by – negative practice-based experience.40,45,54 Community-based service users and carers have described staff who remain indifferent to them,41 and who display an inherent disregard for their views.73 The pivotal role of respect in establishing successful collaborative relationships remains central to users' discourse, and an accumulation of evidence from different clinical settings and research designs belies its significance as one of the more pervasive yet ill-addressed users' needs.23,25,29,33,51,79,92–95 Advocacy has been proffered as one way in which perceived power differentials between service users, carers and mental health professionals might potentially be reduced,84,88,96,97 although empirical evidence of its effect is sparse. Limited qualitative enquiry suggests potential cultural variation in acceptability, and a possibility that users will confront multiple implementation barriers, including a lack of suitable agents to arbitrate on their behalf.54,98

Participatory decision-making

Shared decision-making demands not only that different stakeholders attribute value to their own contributions and those of others but also that there exists perceived equality between them. The existing evidence base remains somewhat ambiguous regarding the extent to which service users may wish to and/or are enabled to attain decision-making control. National and localised surveys have previously evaluated levels of user-involved care planning through the quantification of predetermined ‘success’ criteria, often defined in terms of service users' care planning awareness or their signed endorsement of the resulting care plan. Consensus across these studies suggests that too few people had received a copy of their care plan or had prospectively influenced its development in a meaningful way.2,3,28,32 Limitations in the nature and depth of the data obtained prohibit interpretation in terms of the preferences or intentions of individual service users. Systematic synthesis of qualitative and mixed method evaluations suggests that a key factor influencing people's preferences for care planning involvement may be the timing of their decision-making, specifically whether consultation occurs during a crisis episode. Focus groups conducted with 100 community-based service users in Germany revealed that although service users and carers expressed some uncertainty regarding the former's capacity to make decisions during crisis episodes, they nonetheless advocated enhanced involvement outside of these events.91 A qualitative evaluation of a UK-based local open record initiative also reported that service users desired greater transparency in their clinical notes yet simultaneously remained reluctant to read external appraisals of themselves when they were ill.99 The onus is thus placed firmly on mental health professionals, who must remain sensitive to a delicate but potentially complex interplay between patient autonomy and dependency.25,43,100

The nature of the desired involvement is more difficult to ascertain. Although increasing opportunities for shared decision-making has been identified as a key facilitator of service user-led care planning, interview data obtained from a small sample of community service users have suggested that some individuals may ultimately prefer a more blended decision-making style.40 In this instance service users were observed to seek professional authentication for their own decisions and tended to capitulate to professionals whenever discord was experienced, on the rationale that the provider's perspective was often more compelling than their own. Notably, those interviewed for this study were recruited from a case management service seeking to provide recovery-based care through intensive and sustained contact with service users. The transferability of the data to traditional service delivery models and other clinical settings thus remains unclear. Both national consultation and community surveys suggest that more congruent decisions between service users and professionals are likely to emanate from trusting and respectful relationships developed over time.40,66,101 Thus, although the net outcome of blended decision-making may approximate that of a professionally led care plan, the processes by which care is determined are arguably very different.

The importance of being respected, listened to and believed emerge as key themes across service user and carer discourse. Pre-empting care planning meetings with informal discussion,96 and documenting only plans that have been prospectively endorsed by service users, has been shown to reduce perceptions of coercion and promote a greater sense of user control.102 Qualitative data obtained from in-patient settings contextualises these findings by showing that requests to endorse a paternalistic care plan retrospectively can engender anxiety among service users,100 who may attribute legality to their actions and fear retribution should they fail to comply.72,98,100 Service users have previously been shown to conceptualise such practices as tokenistic, thereby highlighting a potentially important difference between staff and service users in the way that collaboration is construed.

Care planning as a hierarchical event

Dissatisfaction among service users with care planning involvement raises the question of why mental health services have historically failed to enable patients in this way. According to our original frame of reference, influence is likely to incorporate but extend beyond the level of the individual, including both relational and organisational constraints on care.

Care planning at a relational level

Few studies have examined directly the value that mental health staff afford service user and carer involvement in care planning. The only exception is a survey of occupational therapists, which reported that only half of those interviewed intended to involve service users in decisions about their care.103 Although the reasons for this were not elucidated, evidence from alternative sources suggests a combination of attitudinal and skill constraints.32,41,52,67,75,82,89,95,104–107 Modest competencies in partnership working have been reported across multiple professional groups.103,108 Mental health nurses and allied health professionals disclose insufficient experience in patient-led goal formulation and lack knowledge and familiarity with the range of services available to address service users' social needs.52,75,82 A separate body of literature focuses on the potential for service user-centred care to invoke an ethical dilemma for service providers, and highlights variable levels of professional confidence in service users' capacities to cope with increased responsibility for care.41,103 Mixed method surveys of advanced directives suggest that psychiatrists may be more likely to endorse shared decision-making where they perceive service users to have greater insight, higher levels of alliance or treatment adherence,22,109 and/or strong family support for their preferences.110

Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data across a range of service settings underscores the potential for person-centred services to be negated by entrenched perceptions of staff responsibility under statutory mental health law.32,42,85,111 Qualified nursing staff express uncertainty regarding their ability to facilitate therapeutic cooperation, and periodically report an overreliance on professional dialogue to reduce the possibility that service users will refuse an aspect of care they are otherwise deemed to require.112 Small-scale studies in community and in-patient settings have demonstrated that less experienced and preregistration staff value service user involvement more highly than do qualified staff,104,111 although translation of these values into practice is not guaranteed. Cooperative and qualitative enquiry with service users and student nurses suggests these individuals remain driven by their professional role, portraying risk as a key source of tension in their decisions about when and how service users can best be involved.25,85

A competing theme emerging from professional discourse is the perception that service users are at times unwilling to participate in decisions about their own care.73,75,90 Alongside incapacity,90,113 other perceived barriers to participatory decision-making include non-cooperation with treatment,90 and a lack of interest in mental healthcare.75,90,100,113 The reality of these perceptions is difficult to establish. Rigorous qualitative studies exploring the perspectives of people using in-patient services indicate that some may indeed refuse participation, either because they lack motivation,100 or because prior experience suggests that the process will be tokenistic.45,54,112 These data juxtapose larger-scale national surveys and qualitative data from more mixed samples that suggest that the majority of service users continue to advocate greater involvement in the care planning process.21,27,28,31–33,39

Discrepancies between different stakeholder groups and settings raise the long-standing question of whether mental health professionals are intentionally or unintentionally denying service users involvement in their care. Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data suggests that service users and carers remain steadfast in their requests for respect,25,29,30,41,51,78,79,92–94 and perceive some service providers as displaying critical condescension towards them,41 emanating directly from concepts of stigma,91,79,112 or blame.21,25,79,93,101,114 Rigorous qualitative analysis of service user views suggests that some mental health professionals may deliberately seek to retain relational power by presenting themselves as the most knowledgeable group.42,72 Although limited in availability, professional discourse lends some support to this view.78

Heterogeneity within the populations and variables studied makes the true relationships between service user and professional characteristics difficult to establish. Select quantitative studies suggest that clinical experience may influence staff attitudes towards service user involvement, with female and less experienced staff more likely to support collaboration.105 Staff may be more reluctant to involve users with thought disturbance or psychoses,115,56 and individuals with affective disorders have been shown to report higher satisfaction with treatment influence and involvement than those with schizophrenia.80,116 The validity of these relationships is difficult to establish. The potential for professionals' views to be influenced by stigma is supported by small studies that suggest service users' and carers' knowledge may be mediated by demographic or ethnic status.25,57,73,117 Compared with White service users, those from Black and ethnic minority groups may be less likely to be given a copy of their care plan,73 and less likely to have their views and daily needs assessed.3,32,73

Although controlled trials of joint crisis planning document preliminary evidence of effect,118–121 process evaluations suggest that these initiatives can attract professional scepticism, be perceived as an administrative burden and be poorly accessed or adhered to by staff.75,97,98,110,118,122–126 Once again, however, limitations in the amount and depth of data prohibit any firm conclusions regarding the extent to which this behaviour is underpinned by deliberate or misplaced intent. One small survey of in-patient staff has reported service providers opposing the notion that patients should have unrestricted access to clinical notes and rejecting opportunities for patients to make written contributions to their files.104 Additional data suggest that staff may be more willing to acknowledge service user views and more likely to consent to initiatives aimed at addressing their needs in instances when service users highlight previously unidentified goals.127 Although premised on a limited evidence base, this observation raises the possibility that professional resistance to service user involvement may depend less upon clinicians' reluctance to foster relational equality per se, and more upon which party is afforded greater status as the original purveyor of need.127

Conveying familiarity with service users' preferences has been shown to contribute to an individual's perception of being known.58,102 Increasing opportunities for service users to identify and communicate their needs effectively thus hold promise as an effective means by which to enhance satisfaction with mental health services and specifically with user-involved care. An accumulation of quantitative and qualitative evidence suggests that in order to achieve this routinely, staff may need to engage more intensively and consistently with service users.21,25,40,62,78,91,101,128 Insufficient contact with mental health professionals has previously been shown to erode service user trust and reduce the possibility that this dyad will discuss issues that will augment and extend a medical model of care.25

Care planning at the organisational level

Triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data has already shown that meaningful service user involvement is likely to depend upon the reorientation of the attitudes and practices of more than one stakeholder group. Qualitative synthesis further suggests that this reorientation in turn demands effective and demonstrable organisational support.44,45,75,100 In order to increase scope for involvement, service users advocate that services should be more critical of their tendency to medicalise service user experiences and their predisposition towards diagnostically driven care.25,41,43,45,48,50,85 The maintenance and dominance of a service model in which the majority of decisions rest with a psychiatrist,21,32 has specifically been implicated in preventing other mental health professionals from practising in an empowering way.41,85

System constraints that increase caseloads,129 and/or limit staff contact time, have directly been blamed for the failure of mental health services to fully involve service users and carers in their care.32,79,108 Qualitative discourse has historically portrayed mental health staff as overworked, stressed and suffering from compassion fatigue, albeit with some variation across clinical service settings.22,44,95,112 Interviews undertaken with acute and community care staff highlight practice environments that are ritualised and excessively task-oriented,43,44,85 and it has previously been questioned whether or not these staff have the necessary time and support to meet their clients' holistic needs.48,95 Innovative training initiatives aimed at enhancing nursing skills show preliminary evidence of effect.107,130 In-depth process evaluations report longer-term implementation to be constrained by ritualised care environments, high staff turnover, low organisational support for user-involved care planning and insufficient commitment to professional and team development.43,44,79,95,129

Care planning inevitably necessitates interactions between different stakeholder groups and the context and quality of these interactions may directly affect the way in which the meaning of the event is construed. Across clinical settings, administrative and communicative breakdowns have been implicated in services' failures to appoint or make care coordinators accessible to service users.64,68,74,87,131 Service users and carers report insufficient notification of care planning meetings,88,132 poor documentation of care planning outcomes,48 and a lack of warning regarding treatment changes or scheduled review.28,69,131 Specific communication failures have been identified between in-patient and community staff,41 and between mental health nurses, psychiatrists and general practitioners.111 Poor interagency communication has been cited both as a reason for low staff attendance at care planning meetings,41 and as a barrier to professionals accessing written evidence of service users' preferences during crisis.97 Triangulation of these data suggests that some services may ultimately have reduced care planning to an event in which providers outline their responsibilities to service users, rather than upholding its conceptualisation as a collaborative and prospective process through which both parties can holistically address the service user's recovery-based needs.

Central to discourse is the notion that service users and carers can feel intimidated or ignored during care planning meetings.73 Intimidation arises both from the physical environment in which the meeting takes place and from the formality with which it is conducted.72,75,82,84 By virtue of their very location, care planning meetings conducted within a clinical environment bring with them perceptions of illness and relinquished control.56,72,111 Other key criticisms include excessive levels of staff attendance at care planning consultations,44,73,111 the presence of unknown staff or of staff not directly involved in a person's care,73 and the failure of professionals to acknowledge or introduce meeting attenders.73 Restrictions on the amount of time that professionals are able to allocate to care planning,73,84 and the subsequent speed with which decisions are made, have additionally been reported to deter service user involvement.72,73,90

Access barriers on the part of service users and carers have also been acknowledged and include geographical distance, competing caring responsibilities and economic constraints that prohibit attendance at care planning consultations within routine hours.65,88,95 Organisational mechanisms that have been postulated to overcome these difficulties include the provision of open accessible care teams, staff who are validated in spending time with service users and carers, and services that offer flexibility in the timing and venue of care planning meetings.45,47,51,56,58,78,79,96,108,133 A proxy indicator for service user satisfaction with care planning involvement may thus be not only the degree to which mental health services recognise the importance of service user and carer participation, but also the extent to which they display tangible commitments to facilitating this process.44,45,75,100

Discussion

We conducted a narrative synthesis of empirical data to examine systematically how the ideology of service user and carer involvement in care planning is operationalised within secondary mental health services. Theory articulation allowed for the conceptualisation of user-involved care planning as both a linear and a hierarchical event. Synthesis showed that failures in partnership working typically occur at points where the frames of reference of service users and providers diverge. Although service users and carers remain sensitive to hierarchical and relational aspects of care, service providers may not routinely optimise these influences. By failing to acknowledge or respond adequately to the social and organisational contexts in which care occurs, secondary services have arguably reduced care planning to a linear, task-focused event. In a linear model success is defined primarily in terms of outcome (i.e. the derivation of a care plan) rather than the quality of the process through which this is achieved. This observation provides one rationale for why local and national care quality surveys have historically monitored the extent to which care plans are signed by service users (e.g. Warner, Beeforth et al),32,62 rather than the degree to which genuine prospective involvement is evident. Cause and effect is difficult to establish, however. It is equally possible, for example, that user-involved care planning has over time been diluted to a series of practice-based activities designed to comply with auditor standards, rather than enhancing the quality of the experience that these standards were originally designed to deliver. Quantifiable performance indicators are advantageous to audit and clinical research and in themselves may not be detrimental to meaningful patient-centred interactions. Empirical evidence is nonetheless accumulating to suggest that across community and in-patient settings a combination of individual, time and organisational constraints may ultimately be acting to dilute professional education and training, replacing a contemporary philosophy of service user and carer involvement in care planning with ritualised, task-oriented practice.

Barriers to collaboration

Synthesis of the existing evidence base reveals weaknesses in three of four stages central to service user involvement. Although substantial evidence suggests that service users are sufficiently motivated to collaborate in care planning,21,26–33,39,40 subsequent and substantial barriers are created through poor information exchange and insufficient opportunities for care negotiation. The net effect is that the primary driver of service user involvement typically remains one of tokenism rather than genuine patient-centred care.23,39 The lack of recognition that has historically been afforded to the relational and hierarchical elements of care planning processes has created a marked mismatch between client motivation and information exchange, such that service users' knowledge is often rendered insufficient for shared need assessments or care negotiation to occur. Our review has highlighted potential for enhanced information exchange to improve service users' and carers' perceptions of involvement independently of the service user acquiring full decision-making control. Opening up lines of communication between service users and providers is thus likely to represent an important and necessary step in improving the extent and quality of service user and carer involvement.

The sheer number of studies included in the review illustrates that research interest in user-involved care planning remains high, suggesting a failure to systematically translate evidence into practice. An update to our original search was performed in May 2014, which identified a further five papers meeting our inclusion criteria.134–138 Although all were small studies focused on specific clinical populations,134,136,138 or on variants of care planning,135,137 their data corroborated our synthesis, highlighting the following ongoing barriers to service user involvement: ritualised practices;136,138 insufficient information provision;134,135,138 lack of service user confidence,138 or competence;135 and professional scepticism.137 Effective involvement will aIways depend on the skills and competencies of the parties involved, and it is arguable whether all service users and carers possess the necessary skills and confidence to work collaboratively with mental health professionals. Likewise, levels of staff engagement are likely to be influenced by a complex mix of intra-individual attitudes, prejudices, competencies and team philosophies, all of which may require redress and realignment before meaningful service user involvement can occur. Staff training initiatives that seek to improve staff awareness and sensitivities in user-involved care planning have been developed and evaluated as a potentially effective means by which to achieve this goal.63,107,130

A key finding of our review is that different variants of care planning are likely to be conceptualised very differently by service users, whose motivation and capacity for involvement will ultimately depend upon the extent to which clinical practice is judged to complement their own recovery-based needs. Future interventions aimed at enhancing interindividual relationships for care planning will thus also need to consider in detail the values, priorities and care philosophies upheld by the organisational context in which care occurs.

Service user-involved care planning aligns closely with the UK's personalisation agenda advocated by adult social care. The success of this agenda relies heavily upon system transformation to ensure that both staff and service users are equipped to engage in informed decision-making against the backdrop of fluctuating mental health symptoms and a traditionally risk-averse organisational culture. Longer-term reorientation to the premise and conduct of partnership working is likely to necessitate that staff not only review their practice but are encouraged and supported to do so through an integrated and sustained system of professional accountability and development. Reminiscent of the recommendations of the Francis enquiry,8 mental health trusts need to embed a culture of compassionate, collaborative care into the organisation and delivery of secondary care services. Staff must be enabled to, and feel validated in, spending time with service users so that the pace of consultation and service users' understanding of and contribution to the care planning process are not governed solely by administrative efficiency. A key challenge in the personalisation agenda lies in knowing how best to implement individualised care without concomitantly increasing procedural bureaucracy and risk-management strategies to an unsustainable level. It is inevitable that similar challenges will be encountered in user-involved care planning.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings are tempered by significant methodological and clinical heterogeneity in the primary studies we reviewed. Owing to the nature of the research question and our focus on barriers and enablers of user-involved care planning, meta-analysis of quantitative satisfaction data was not performed. The existing evidence tends towards the views of service users rather than carers or providers, and rigorous qualitative studies detailing the experiences of these stakeholder groups are sparse. Although there is inevitably a risk of bias in prioritising one party's perspective over another, the wealth and consistency of data reviewed and the systematic approach to its synthesis raises confidence in the validity of our findings. Concepts of service user involvement in mental health services have historically been driven by policy rather than health service theory. The theoretical framework that was developed to guide our narrative was thus a contemporaneous one, enabling a disparate and varied knowledge base to be synthesised in manner that bore most relevance to current practice.

Our review took an international perspective enabling the holistic identification of potential as well as existing barriers and enablers to user-involved care planning. Potential for regional and national variation in the level and organisational context of service user involvement is acknowledged. Within the UK, for example, discrete differences exist in the statutory requirements for service user involvement in care planning between England and Wales. Nonetheless, the consistency and duration over which service users and carers have reported dissatisfaction with user-involved care planning supports the notion that traditional methods of communication between professionals and their clients have failed. Future commitments to addressing service users' and carers' needs are likely to include the increased provision of service user-centred materials and resources, and a more flexible strategy for engaging service users and carers in clinically led consultations, possibly through remote communication links with multidisciplinary teams.75

Encouragingly, evidence is available to suggest that the failure of staff to facilitate adequate service user involvement does not have to be a fixed phenomenon. Where organisational change initiatives have been imposed on routine practice, greater collaboration has been achieved. Positive team level effects include a greater validation of time spent with service users and improved job satisfaction among staff.4 High staff morale is thus implicated as both an outcome and a driver of partnership working, thereby highlighting a possible interdependency between meaningful user-involved care planning and high-quality service user–staff communication.

Future directions

To confirm and improve on the different theories proposed here, rigorous evaluations of the implementation of service user- and carer-involved care planning are now required. Research and clinical initiatives that aim to enhance current levels of user and carer-involved care planning and explore fully the barriers and facilitators to their implementation are crucial to confirming or refuting our understanding of the key mechanisms involved.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None.

Funding

This work was funded by the UK NIHR Programme Development Grant Scheme.

References

- 1. Department of Health No Health without Mental Health: A Cross-Government Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of all Ages. Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Healthcare Commission The Pathway to Recovery: A Review of NHS Acute Inpatient Mental Health Services. Healthcare Commission, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health Refocusing the Care Programme Approach. Policy and Positive Practice Guidance. Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver T, Bhui K, Fulop N, et al. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ 2002; 325: 1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Care Quality Commission Survey of Mental Health Inpatient Services. Care Quality Commission, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Healthcare Commission Community Mental Health Service Users' Survey. Healthcare Commission, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bee P, Playle J, Lovell K, Barnes P, Gray R, Keeley P. Service user views and expectations of UK-registered mental health nurses: a systematic review of empirical research. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45: 442–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Mid Staffordshire Foundation Inquiry Independent Inquiry into Care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005–March 2009, vols 1,2 TSO (The Stationery Office), 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Munro K, Ross KM, Reid M. User involvement in mental health: time to face up to the challenges of meaningful involvement? Int J Ment Health Promot 2006; 8: 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins J, Green S. (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carlson MD, Morrison RS. Study design, precision, and validity in observational studies. J Palliat Med 2009; 12: 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Institute of Health Research, University of Lancaster, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A, Oliver S, Sutcliffe K, Rees R, et al. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 2004; 328: 1010–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. Government Chief Social Researcher's Office, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. BSA Medical Sociological Group Criteria for the evaluation of qualitative research papers. Medical Sociology News 1996; 22: 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51: 1087–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 60: 301–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hickey G, Kipping C. Exploring the concept of user involvement in mental health through a participation continuum. J Clin Nurs 1998; 7: 83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rethink, Adfam Living with Severe Mental Health and Substance Use Problems: Report from the Rethink Dual Diagnosis Research Group. Rethink & Adfam, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antoniou J, Estop G, Gilburt H. Advance Directives in 2006: A Report. Rethink, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faulkner A, Williams K. Future Perfect. Rethink, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pitt L, Kilbride M, Nothard S, Welford M, Morrison AP. Researching recovery from psychosis: a user-led project. Psychiatr Bull 2007; 31: 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tee S, Lathlean J, Herbert L, Coldham T, East B, Johnson TJ. User participation in mental health nurse decision-making: a co-operative enquiry. J Adv Nurs 2007; 60: 135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bramesfeld A, Wedegartner F, Elgeti H, Bisson S. How does mental health care perform in respect to service users' expectations? Evaluating inpatient and outpatient care in Germany with the WHO responsiveness concept. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; 7: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Healthcare Commission Patient Survey Report 2004. Picker Institute: Europe, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Healthcare Commission No Voice, No Choice: A Joint Review of Adult Community Mental Health Services in England. Healthcare Commission, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howard PB, El-Mallakh P, Kay Rayens M, Clark JJ. Consumer perspectives on quality of inpatient mental health services. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2003; 17: 205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schene AH, Van Wijngaarden B. A survey of an organization for families of patients with serious mental illness in The Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46: 807–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rose D, Ford R, Lindley P, Gawith L, KCW Mental Health Monitoring Users' Group In Our Experience: User-focused Monitoring of Mental Health Services in Kensington & Chelsea and Westminster Health Authority. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Warner L. Back on Track: CPA Care Planning for Service Users Who Are Repeatedly Detained Under the Mental Health Act. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borneo A. Your Choice. Results from the Your Treatment, Your Choice Survey: Final Report. Rethink, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turner D. Recovery in NSF ’Wild Geese’. National Schizophrenia Fellowship, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hope R. The Ten Essential Shared Capabilities – A Framework for the Whole of the Mental Health Workforce. Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tessler RC, Gamache GM, Fisher GA. Patterns of contact of patients' families with mental health professionals and attitudes toward professionals. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42: 929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Whelton C, Pawlick J, Cardamone J. Involving families in psychosocial rehabilitation. Psychiatr Rehabil J 1997; 20: 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wooff D, Schneider J, Carpenter J, Brandon T. Correlates of stress in carers. J Ment Health 2003; 12: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rose D. Users' Voices: The Perspectives of Mental Health Service Users on Community and Hospital Care. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Woltmann E, Whitley R. Shared decision making in public mental health care: perspectives from consumers living with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2010; 34: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goodwin V, Happell B. In our own words: consumers' views on the reality of consumer participation in mental health care. Contemp Nurse 2006; 21: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dobie MS, Bulia S, Swanke J. Patient-centered mental health care: encouraging caregiver participation. Care Manag J 2010; 11: 146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Piippo J, Aaltonen J. Mental health care: trust and mistrust in different caring contexts. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 2867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cambridge P, Forrester-Jones R, Carpenter J, Tate A, Knapp M, Beecham J, et al. The state of care management in learning disability and mental health services 12 years into community care. Br J Soc Work 2005; 35: 1039–62. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Daremo A, Haglund L. Activity and participation in psychiatric institutional care. Scand J Occup Ther 2008; 15: 131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rose D. Partnership, co-ordination of care and the place of user involvement. J Ment Health 2003; 12: 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perkins RE, Fisher NR. Beyond mere existence: the auditing of care plans. J Ment Health 1996; 5: 275–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health Acute Problems: A Survey of the Quality of Care in Acute Psychiatric Wards. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams CC. Discharge planning process on a general psychiatry unit. Soc Work Ment Health 2003; 2: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schmidt-Posner J, Jerrell JM. Qualitative analysis of three case management programs. Community Ment Health J 1998; 34: 381–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schroder AG, Ahlstrom G, Larsson BW. Patients' perceptions of the concept of the quality of care in the psychiatric setting: a phenomenographic study. J Clin Nurs 2006; 15: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murphy N, Cutts H. Can the introduction of a quality of life tool affect individual professional practice and the quality of care planning in a community mental health team? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2009; 16: 941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sutherby K, Szmukler GI, Halpern A, Alexander M, Thornicroft G, Johnson C, et al. A study of ‘crisis cards’ in a community psychiatric service. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Amering M, Stastny P, Hopper K. Psychiatric advance directives: qualitative study of informed deliberations by mental health service users. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186: 247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Oshima I, Cho N, Takahashi K. Effective components of a nationwide case management program in Japan for individuals with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J 2004; 40: 525–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Henderson C, Jackson C, Slade M, Young AS, Strauss JL. How should we implement psychiatric advance directives? Views of consumers, caregivers, mental health providers and researchers. Adm Policy Ment Health 2010; 37: 447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alegria M, Polo A, Gao S, Santana L, Rothstein D, Jimenez A, et al. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Med Care 2008; 46: 247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chan S, MacKenzie A, Ng DT, Leung JK. An evaluation of the implementation of case management in the community psychiatric nursing service. J Adv Nurs 2000; 31: 144–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eisen SV, Dickey B, Sederer LI. A self-report symptom and problem rating scale to increase inpatients' involvement in treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51: 349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Macpherson R, Summerfield L, Haynes R, Slade M, Foy C. The use of carers' and users' expectations of services (CUES) in an epidemiological survey of need. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2005; 51: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. O'Donnell M, Proberts M, Parker G. Development of a consumer advocacy program. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998; 32: 873–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Beeforth M, Colan E, Graley R. Have We Got Views for You. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Berger JL. Incorporation of the tidal model into the interdisciplinary plan of care – a program quality improvement project. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2006; 13: 464–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Webb Y, Clifford P, Fowler V, Morgan C, Hanson M. Comparing patients' experience of mental health services in England: a five-Trust survey. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2000; 13: 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lakeman R. Practice standards to improve the quality of family and carer participation in adult mental health care: an overview and evaluation. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2008, 17: 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sandlund M, Hansson L. Patient satisfaction in a comprehensive sectorized psychiatric service: study of a 1-year-treated incidence cohort. Nord J Psychiatry 1999; 53: 305–12. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cresswell J, Lelliott P. (eds). Accreditation for Inpatient Mental Health Services (AIMS): National Report for Working Age Acute Wards: July 2007–July 2009. Royal College of Psychiatrists' Centre for Quality Improvement, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bowers L. Monitoring the outcome of case management and community care: the care programme approach support system (CPASS). J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1997; 4: 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Perreault M, Paquin G, Kennedy S, Desmarais J, Tardif H. Patients' perspective on their relatives' involvement in treatment during a short-term psychiatric hospitalization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34: 157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rethink Mind. New Horizons Engagement Event: People Who Use Mental Health Services And Carers. Rethink & Mind, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marshall TB, Solomon P. Releasing information to families of persons with severe mental illness: a survey of NAMI members. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51: 1006–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McDermott G. The care programme approach: a patient perspective. Nurs Times 1998; 94: 57–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Allen C. The care programme approach: the experiences and views of carers. Ment Health Care 1998; 1: 160–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Brown Z. The care programme approach – the service user's view. Soc Serv Res 1998; 4: 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Storm M, Davidson L. Inpatients' and providers' experiences with user involvement in inpatient care. Psychiatr Q 2010; 81: 111–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tanenbaum SJ. Psychiatrist–consumer relationships in US public mental health care: consumers' views of a disability system. Disabil Soc 2009; 24: 727–38. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Walsh J, Boyle J. Improving acute psychiatric hospital services according to inpatient experiences. A user-led piece of research as a means to empowerment. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2009; 30: 31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Askey R, Holmshaw J, Gamble C, Gray R. What do carers of people with psychosis need from mental health services? Exploring the views of carers, service users and professionals. J Fam Ther 2009; 31: 310–31. [Google Scholar]

- 79. McAuliffe D, Andriske L, Moller E, O'Brien M, Breslin P, Hickey P. ‘Who cares?’ An exploratory study of carer needs in adult mental health. Aust e-J Adv Ment Health 2009; 8: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Svensson B, Hansson L. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care: the influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90: 379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health Pulling Together: The Future Roles and Training of Mental Health Staff. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Simpson A. Creating alliances: the views of users and carers on the education and training needs of community mental health nurses. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1999; 6: 347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wolfe J, Gournay K, Norman S, Ramnoruth D. Care programme approach: evaluation of its implementation in an inner London service. Clin Eff Nurs 1997; 1: 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Magorrian K. Responding to the needs of carers of people with schizophrenia. Prof Nurs 2001; 17: 225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. O'Donovan A. Patient-centred care in acute psychiatric admission units: reality or rhetoric? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2007; 14: 542–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Princess Royal Trust for Carers The Princess Royal Trust for Carers ‘Out of Hospital’ Project – Learning from the Pilot Projects Final Report – May 2010. Acton Shapiro, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ford R, Rose D. Mental health. Heads and tales. Health Serv J 1997; 107: 28–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Loveland B. The care programme approach: whose is it? Empowering users in the care programme process. Educational Action Research 1998; 6: 321–35. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rea CA, Rea DM. Responding to user views of service performance. J Ment Health 2000; 9: 351–63. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chinman MJ, Allende M, Weingarten R, Steiner J, Tworkowski S, Davidson L. On the road to collaborative treatment planning: consumer and provider perspectives. J Behav Health Serv Res 1999; 26: 211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bramesfeld A, Klippel U, Seidel G, Schwartz FW, Dierks ML. How do patients expect the mental health service system to act? Testing the WHO responsiveness concept for its appropriateness in mental health care. Soc Sci Med 2007; 65: 880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ferry JL, Abramson JS. Toward understanding the clinical aspects of geriatric case management. Soc Work Health Care 2005; 42: 35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. O'Brien L. The relationship between community psychiatric nurses and clients with severe and persistent mental illness: the client's experience. Aust NZ J Ment Health Nurs 2001; 10: 176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Schroder A, Ahlstrom G. Psychiatric care staff's and care associates' perceptions of the concept of quality of care: a qualitative study. Scan J Caring Sci 2004; 18: 204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Goodwin V, Happell B. To be treated like a person: the role of the psychiatric nurse in promoting consumer and carer participation in mental health service delivery. J Psychiatr Nurs Res 2008; 14: 1766–75. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Diamond B, Parkin G, Morris K, Bettinis J, Bettesworth C. User involvement: substance or spin? J Ment Health 2003; 12: 613–26. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Garcia I, Kennett C, Quraishi M, Duncan G. Acute Care 2004: A National Survey of Adult Psychiatric Wards in England. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Van Dorn RA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. Preferences for psychiatric advance directives among Latinos: views on advance care planning for mental health. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 1383–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Alexander J, Rogers K, Simpson R, Rigby P. The value of client held records. Mental Health Nursing 2002; 22: 12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Linhorst DM, Hamilton G, Young E, Eckert A. Opportunities and barriers to empowering people with severe mental illness through participation in treatment planning. Soc Work 2002; 47: 425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Shaul JA, Eisen SV, Stringfellow VL, Clarridge BR, Hermann RC, Nelson D, et al. Use of consumer ratings for quality improvement in behavioral health insurance plans. J Comm J Qual Improv 2001; 27: 216–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ware NC, Tugenberg T, Dickey B. Practitioner relationships and quality of care for low-income persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2004; 55: 555–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ceramidas DM, Forn de Zita C, Eklund M, Kirsh B. The 2009 world team of mental health occupational therapists: a resilient and dedicated workforce. The Bulletin: World Federation of Occupational Therapists 2009; 60: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 104. McCann TV, Baird J, Clark E, Lu S. Mental health professionals' attitudes towards consumer participation in inpatient units. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2008; 15: 10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. McCann TV, Clark E, Baird J, Lu S. Mental health clinicians' attitudes about consumer and consumer consultant participation in Australia: a cross-sectional survey design. Nurs Health Sci 2008; 10: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Goss C, Moretti F, Mazzi MA, Del Piccolo L, Rimondini M, Zimmermann C. Involving patients in decisions during psychiatric consultations. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193: 416–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Barnes D, Carpenter J, Dickinson C. The outcomes of partnerships with mental health service users in interprofessional education: a case study. Health Soc Care Community 2006; 14: 426–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ennals P, Fossey E. The Occupational Performance History Interview in community mental health case management: consumer and occupational therapist perspectives. Aust Occup Ther J 2007; 54: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Coffey DS. Connection and autonomy in the case management relationship. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2003; 26: 404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Elbogen EB, Swartz MS, Van Dorn R, Swanson JW, Kim M, Scheyett A. Clinical decision making and views about psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57: 350–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Carpenter J, Sbaraini S. Involving service users and carers in the care programme approach. J Ment Health 1996; 5: 483–8. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Corring DJ, Cook JV. Client-centred care means that I am a valued human being. Can J Occup Ther 1999; 66: 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, Busch R, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al. Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 114: 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Beebe TJ, Harrison PA, McRae JA, Asche SE. Evaluating behavioral health services in Minnesota's Medicaid population using the Experience of Care and Health Outcomes (ECHO) Survey. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2003; 14: 608–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Corrigan PW, Buican B, McCracken S. Can severely mentally ill adults reliably report their needs? J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184: 523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ostman M, Wallsten T, Kjellin L. Family burden and relatives' participation in psychiatric care: are the patient's diagnosis and the relation to the patient of importance? Int J Soc Psychiatry 2005; 51: 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Blenkiron P, Mo KH, Cuzen J, Hammill AC. Involving service users in their mental health care: the CUES Project. Psychiatr Bull 2003; 27: 334–8. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Henderson C, Swanson JW, Szmukler G, Thornicroft G, Zinkler M. A typology of advance statements in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Henderson C, Lee R, Herman D, Dragasti D. From psychiatric advance directives to the joint crisis plan. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 1390–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Van Dorn RA, Ferron J, Wagner HR, et al. Facilitated psychiatric advance directives: a randomized trial of an intervention to foster advance treatment planning among persons with severe mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1943–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Van Dorn RA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen E, Ferron J. Reducing barriers to completing psychiatric advance directives. Adm Policy Ment Health 2008; 35: 440–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Elbogen E, Swanson JW, Appelbaum PS, Swartz MS, Ferron J, Van Dorn RA, et al. Competence to complete psychiatric advance directives: effects of facilitated decision making. Law Hum Behav 2007; 31: 275–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kim MM, Van Dorn RA, Scheyett AM, Elbogen EE, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al. Understanding the personal and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives: a qualitative perspective. Psychiatry 2007; 70: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Papageorgiou A, King M, Janmohamed A, Davidson O, Dawson J. Advance directives for patients compulsorily admitted to hospital with serious mental illness. Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181: 513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Srebnik DS, Russo J. Consistency of psychiatric crisis care with advance directive instructions. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58: 1157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Papageorgiou A, Janmohamed A, King M, Davidson O, Dawson J. Advance directives for patients compulsorily admitted to hospital with serious mental disorders: directive content and feedback from patients and professionals. J Ment Health 2004; 13: 379–88. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Hansen T, Hatling T, Lidal E, Ruud T. The user perspective: respected or rejected in mental health care? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004; 11: 292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Angell B, Mahoney C. Reconceptualizing the case management relationship in intensive treatment: a study of staff perceptions and experiences. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007; 34: 172–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Lawn S, Battersby MW, Pols RG, Lawrence J, Parry T, Urukalo M. The mental health expert patient: findings from a pilot study of a generic chronic condition self-management programme for people with mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2007; 53: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Richards D, Bee P, Loftus S, Baker J, Bailey L, Lovell K. Specialist educational intervention for acute inpatient mental health nursing staff: service user views and effects on nursing quality. J Adv Nurs 2005; 51: 634–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Ryan T, Pearsall A, Hatfield B, Poole R. Long term care for serious mental illness outside the NHS: a study of out of area placements. J Ment Health 2004; 13: 425–9. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Social Action for Health Hear I Am: Mental Health Service Users, Ward Life and Relationships. Social Action for Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 133. Modrcin M, Rapp CA, Poertner J. The evaluation of case management services with the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann 1988; 11: 307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Livingston JD, Nijdam-Jones A, Team P.E.E.R. Perceptions of treatment planning in a forensic mental health hospital: a qualitative participatory action research study. Int J Forensic Ment Health 2013; 12: 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 135. Shields LS, Pathare S, van Zelst SDM, Dijkkamp S, Narasimhan L, Bunders JG. Unpacking the psychiatric advance directive in low resource settings: an exploratory qualitative study in Tamil Nadu, India. Int J Ment Health Syst 2013; 7: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Patton D. Strategic direction or operational confusion: level of service user involvement in Irish acute admission unit care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2013; 20: 387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Van der Ham AJ, Voskes Y, van Kempen N, Broerse JEW, Widdershoven GA. The implementation of psychiatric advance directives: experiences from a Dutch crisis card initiative. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2013; 36: 119–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Rogers B, Dunne E. A qualitative study on the use of the care programme approach with individuals with borderline personality disorder: a service user perspective. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2013; 51: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]