ABSTRACT

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein (Env) trimer, which consists of the gp120 and gp41 subunits, is the focus of multiple strategies for vaccine development. Extensive Env glycosylation provides HIV-1 with protection from the immune system, yet the glycans are also essential components of binding epitopes for numerous broadly neutralizing antibodies. Recent studies have shown that when Env is isolated from virions, its glycosylation profile differs significantly from that of soluble forms of Env (gp120 or gp140) predominantly used in vaccine discovery research. Here we show that exogenous membrane-anchored Envs, which can be produced in large quantities in mammalian cells, also display a virion-like glycan profile, where the glycoprotein is extensively decorated with high-mannose glycans. Additionally, because we characterized the glycosylation with a high-fidelity profiling method, glycopeptide analysis, an unprecedented level of molecular detail regarding membrane Env glycosylation and its heterogeneity is presented. Each glycosylation site was characterized individually, with about 500 glycoforms characterized per Env protein. While many of the sites contain exclusively high-mannose glycans, others retain complex glycans, resulting in a glycan profile that cannot currently be mimicked on soluble gp120 or gp140 preparations. These site-level studies are important for understanding antibody-glycan interactions on native Env trimers. Additionally, we report a newly observed O-linked glycosylation site, T606, and we show that the full O-linked glycosylation profile of membrane-associated Env is similar to that of soluble gp140. These findings provide new insight into Env glycosylation and clarify key molecular-level differences between membrane-anchored Env and soluble gp140.

IMPORTANCE A vaccine that protects against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection should elicit antibodies that bind to the surface envelope glycoproteins on the membrane of the virus. The envelope glycoproteins have an extensive coat of carbohydrates (glycans), some of which are recognized by virus-neutralizing antibodies and some of which protect the virus from neutralizing antibodies. We found that the HIV-1 membrane envelope glycoproteins have a unique pattern of carbohydrates, with many high-mannose glycans and also, in some places, complex glycans. This pattern was very different from the carbohydrate profile seen for a more easily produced soluble version of the envelope glycoprotein. Our results provide a detailed characterization of the glycans on the natural membrane envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1, a carbohydrate profile that would be desirable to mimic with a vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), the causative agent of AIDS, currently infects more than 35 million people globally (1–3). With no cure for the disease, the development of an HIV-1 vaccine is a top public health priority. The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) spike is the only part of the virus accessible to neutralizing antibodies; therefore, Env has been a target of intense investigation as a vaccine immunogen (4, 5). Env is a trimer consisting of three gp120 exterior glycoproteins and three gp41 transmembrane glycoproteins. The gp160 Env precursor is extensively modified by high-mannose glycans, and after proteolytic maturation, some of these are converted to complex carbohydrates. This extensive degree of glycosylation, a feature of Env that contributes to the biology of HIV-1 infection, is the focus of the current study.

More than half of the mass of Env is composed of glycans, which contribute to viral biology in a number of ways (5, 6). They are a prerequisite for the proper folding of Env, which is required for protein function (7, 8). They also protect the protein from detection by the immune system, by producing a “glycan shield” (9, 10). As a result of the masking of underlying protein epitopes, a very large portion of the protein is immunologically “silent,” creating pathways for immune escape (11). In these two examples, the glycans can be viewed as amorphous masses that impact protein structure and shield the protein surface from antibodies. If these were the only roles of the glycans, one might conclude that their presence is necessary but that the type of glycan occupying each site is somewhat irrelevant.

Mounting evidence exists to show that the type of glycan present on Env does, in fact, play a very significant role in the biological properties and particularly in the immunogenicity of this protein. For example, immunogenicity studies of the gp120 exterior Env glycoprotein show that a decrease in the sialic acid content of the glycans can increase the immunogenicity of the protein (12). Other supporting work provides additional evidence that altered glycosylation resulting from changes in the expression conditions of the protein can impact the binding of gp120 to anti-HIV-1 antibodies from human sera (13). Additionally, in many instances, a specific glycan is involved in the recognition of Env by broadly neutralizing antibodies, and glycan specificity is necessary for these antibodies to bind optimally. High-mannose glycans have been shown to be critical to the binding of one of the first broadly neutralizing antibodies identified, 2G12 (14). Since that work, a number of other broadly neutralizing antibodies have also been shown to contain specific types of glycans in their recognition elements (15–20). In fact, many of the antibodies that are of great current interest contact a glycan as a component of their epitope; these include antibodies PG9, PG16, PGT121, PGT125-128, PGT130, PGT135, and CH01-04 (15–20). In sum, these studies demonstrate that the mere presence of glycosylation on Env is not sufficient to guarantee faithful mimicry of the native Env spike. Rather, the right types of glycans must be present in the right places.

To capitalize on this realization, researchers have been working to identify the glycosylation profile of the most native form of Env that can be readily produced and analyzed. These studies have been pioneered by Chris Scanlan and coworkers, who studied glycosylation on virions produced from a variety of cell types (21, 22). Their results suggested that the Env glycosylation profile was surprisingly simple, consisting almost exclusively of high-mannose glycans, and furthermore, that these glycans were present irrespective of the type of cell producing the virus. We expand on these seminal findings here, further asking the question: are high-mannose glycans the most abundant glycoform at every site on Env, or is glycan heterogeneity more complex when profiled on a site-by-site basis? By conducting a site-by-site analysis of a primary HIV-1 Env trimer isolated from the plasma membranes of CHO cells, we provide the first high-fidelity map of a native glycosylation profile for Env. As demonstrated here, the glycosylation profile of Env is not simply an entourage of high-mannose glycans. Indeed, processed glycans predominate at particular sites. These information-rich studies can immediately assist our understanding of native Env glycosylation and provide a foundation for relating differences in glycosylation to differences in immunogenicity between membrane-anchored and soluble forms of the protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and materials.

Trizma hydrochloride, Trizma base, urea, dithiothreitol (DTT), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), iodoacetamide (IAM), ammonium hydroxide, citric acid, sodium citrate trihydrate, and glacial acetic acid were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Other materials used in this study included Optima grade formic acid and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific), HPLC grade water (Honeywell Burdick and Johnson), sequencing grade trypsin and chymotrypsin (Promega), glycerol-free peptidyl-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) cloned from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (New England BioLabs), and endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H) cloned from Streptomyces plicatus (EMD Millipore). All reagents and buffers were prepared with deionized water purified to at least 18 MΩ with a Millipore Direct-Q 3 water purification system.

Expression, solubilization, and purification of HIV-1 JR-FL membrane-anchored Env trimers.

For expression of the membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 glycoproteins, the env cDNA was codon-optimized and was cloned into an HIV-1-based lentiviral vector. These Env sequences comprised a heterologous signal sequence from CD5 in place of that of wild-type HIV-1 Env. The proteolytic cleavage site between gp120 and gp41 was altered, substituting serine residues for Arg 508 and Arg 511. In the JR-FL Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 glycoproteins, the Env cytoplasmic tail was modified by replacement of the codons for Tyr 712 and Lys 808, respectively, with sequences encoding a (Gly)2(His)6 tag and a (Gly)3(His)6 tag, respectively, followed immediately by a TAA stop codon. For control over Env expression, the JR-FL Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 coding sequences were cloned immediately downstream of the tetracycline (Tet)-responsive element (TRE). Our expression strategy further incorporated an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and a contiguous puromycin (puro) T2A enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) open reading frame (23) downstream of env (TRE-env-IRES-puro.T2A.EGFP).

Exogenous membrane-anchored Env was produced by expression in CHO cells. Briefly, vectors comprising the Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 sequences were packaged, pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G protein, and used to transduce CHO cells (Invitrogen) constitutively expressing the reverse Tet transactivator (rtTA) (24). Transduced cells were incubated for 24 h in a culture medium containing 1 μg/ml of doxycycline (DOX) and were then selected for 5 to 7 days in a medium supplemented with puromycin (10 μg/ml). High-producer clonal cell lines were derived using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) to isolate individual highly EGFP fluorescent cells. The integrity of the recombinant Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 sequences in the clonal lines was confirmed by sequence analysis of PCR amplicons. Clonal cultures were adapted for growth in a serum-free suspension culture medium (CDM4CHO; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). For the production of exogenous Env protein, cells were expanded in a suspension culture using a 14-liter New Brunswick BioFlo 310 fermentor (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) and were treated with 1 μg/ml of DOX after reaching a volume of 10 liters and a density of >4 × 106 cells per ml. After 18 to 24 h of culture with DOX, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, snap-frozen in a dry-ice–ethanol bath, and cryostored at −80°C until analysis. The cell pellets were homogenized in a homogenization buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], and a cocktail of protease inhibitors [Roche Complete tablets]). The plasma membranes were then extracted from the homogenates by ultracentrifugation and sucrose gradient separation. The extracted crude plasma membrane pellet was collected and was solubilized in a solubilization buffer containing 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1% (wt/vol) Cymal-5 (Affymetrix), and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Complete tablets). The membranes were solubilized by incubation at 4°C for 30 min on a rocking platform. The suspension was ultracentrifuged for 30 min at 200,000 × g and 4°C. The supernatant was collected and was mixed with a small volume of preequilibrated Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) beads (Qiagen) for 8 to 12 h on a rocking platform at 4°C. The mixture was then injected into a small column and was washed with a buffer containing 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 M NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, and 0.5% Cymal-5. The bead-filled column was eluted with a buffer containing 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, and 0.5% Cymal-5. The eluted Env(−)Δ712 or Env(−)Δ808 glycoprotein solution was concentrated and was diluted in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.01% Cymal-6 for analysis of glycosylation profiles.

Expression and purification of soluble HIV-1 JR-FL gp140.

The gene encoding HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF, with a deletion of the gp120–gp41 cleavage site(C) and fusion domain (F), was codon-optimized by converting the HIV-1 JR-FL Env amino acid sequences to nucleotide sequences employing the codon usage of highly expressed human housekeeping genes (25). The codon-optimized env gene was synthesized de novo (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) and was cloned in the pcDNA3.1(+)/hygromycin plasmid (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), as described previously (32). The recombinant HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein was purified from serum-free culture supernatants of CHO cells transiently transfected with the pcDNA3.1 plasmid expressing the soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein. Purification was achieved by using Galanthus nivalis lectin-agarose beads (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and the purified protein was stored at −80°C until use. Galanthus nivalis lectin exhibits a preference for (α1,3)-mannose residues and can bind the trimannosyl core of high-mannose and processed glycans.

Deglycosylation of HIV-1 Env trimers.

Samples containing 75 μg of the HIV-1 JR-FL Env glycoproteins were fully and partially deglycosylated with PNGase F and Endo H, respectively. Full deglycosylation was performed by incubating the Env samples with 1 μl of PNGase F solution (500,000 U/ml) for a week at 37°C and pH 8.0. For partial deglycosylation, the pH of the sample solution was adjusted to 5.5 with 200 mM HCl, followed by the addition of 2.5 μl of Endo H (≥3 U/ml). After thorough mixing, the reaction mixture was incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The pH of the deglycosylated samples was adjusted to 8.0 with 300 mM NH4OH prior to tryptic digestion. Deglycosylated samples were digested with trypsin as described below.

Proteolytic digestion of HIV-1 Env trimers.

HIV-1 JR-FL Env samples (75 μg) at a concentration of ∼1 mg/ml were denatured with 6 M urea in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) and were fully reduced using 5 mM TCEP at room temperature for 1 h. Following reduction, cysteine residues were alkylated with 20 mM IAM at room temperature for another hour in the dark. Excess IAM was quenched by adding DTT to a final concentration of 30 mM and incubating for 20 min at room temperature. The reduced and alkylated samples were buffer exchanged and were concentrated using a 30,000 molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) filter (Millipore) prior to protease digestion using trypsin and a combination of trypsin and chymotrypsin. All protease digestions were performed according to the manufacturer's suggested protocols: digestion with trypsin was performed with a 30:1 protein/enzyme ratio at 37°C for 18 h; chymotrypsin digestion was performed with a 20:1 protein/enzyme ratio at 30°C for 10 h; and digestion with the combination of both proteases (a mixture of trypsin and chymotrypsin) was performed using the same protein/enzyme ratio as that used for single-enzyme digestion, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C. The resulting HIV-1 glycoprotein digest was either directly analyzed or stored at −20°C until further analysis. To ensure the reproducibility of the method, protein digestion was performed at least three times on different days with samples obtained from the same batch and analyzed with the same experimental procedure.

Chromatography and mass spectrometry.

High-resolution LC-MS experiments were performed using an linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) equipped with electron transfer dissociation (ETD) that is coupled to an Acquity ultraperformance LC (UPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA). Mobile phases consisted of solvent A (99.9% deionized H2O plus 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (99.9% CH3CN plus 0.1% formic acid). Five microliters of the sample (∼7 μM) was injected onto a C18 PepMap 300 column (300 μm inside diameter by 15 cm; 5 μm particle size; 300 Å pore size; Thermo Scientific Dionex) at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The following CH3CN–H2O multistep gradient was used: 3% solvent B for 5 min, followed by a linear increase to 40% solvent B in 50 min and then a linear increase to 90% solvent B in 15 min. The column was held at 97% solvent B for 10 min before reequilibration. A short wash and blank run were performed between every two samples to ensure that there was no sample carryover. All mass spectrometric analysis was performed in a data-dependent mode as described below. The electrospray ionization (ESI) source was operated under the following conditions: source voltage, 3.0 kV; capillary temperature, 260°C; S-lens value of 45 to 55%. Data were collected in the positive-ion mode. The data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode was set up to sequentially and dynamically select the five most intense ions in the survey scan in the mass range, 300 to 2,000 m/z, for alternating collision-induced dissociation (CID) and ETD in the LTQ linear ion trap using a normalized collision energy of 30% for CID and an ion-ion reaction time of 100 to 150 ms for ETD. Full MS scans were measured at a resolution (R) of 30,000 at m/z 400. Under these conditions, the measured R (full width at half maximum [FWHM]) in the Orbitrap mass analyzer is 20,000 at m/z 1,000 and 17,000 at m/z 1,500.

Glycopeptide identification.

Data were analyzed using GlycoPep DB (26), GlycoPep ID (27), and GlycoMod (28). Details of the compositional analysis have been described previously (29–31). Briefly, compositional analysis of glycopeptides with one glycosylation site was carried out by first identifying the peptide portion from tandem MS (MS-MS) data. The peptide portion was inferred manually or by GlycoPep DB from the Y1 ion, a glycosidic bond cleavage between the two N-acetylglucosamine residues at the pentasaccharide core. Once the peptide sequence was determined, plausible glycopeptide compositions were obtained using the high-resolution MS data and GlycoPep DB, and the putative glycan candidate was confirmed manually by identifying the Y1 ion and glycosidic cleavages from the CID data. Peptide fragment ions from ETD spectra of glycopeptides identified from a preceding CID scan were manually assessed for peptide fragment ions by using ProteinProspector (http://prospector.ucsf.edu). Matched fragment ions within 0.5 Da of the theoretical value were accepted. For glycopeptides with multiple glycosylation sites, experimental masses of glycopeptide ions from the high-resolution MS data were converted to singly charged masses and were submitted to GlycoMod. This program calculates plausible glycopeptide compositions from the set of experimental mass values entered by the user, compares these mass values with theoretical mass values, and then generates a list of plausible glycopeptide compositions within a specified mass error. Plausible glycopeptide compositions in GlycoMod were deduced by providing the mass of the singly charged glycopeptide ion and the enzyme, protein sequence, cysteine modification, mass tolerance, and possible types of glycans present in the glycopeptide. Plausible glycopeptide compositions obtained from the analysis were manually confirmed and validated from CID and ETD data.

Peptide identification.

Deglycosylated peptides were identified by searching raw data acquired on the LTQ Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer against a custom HIV database with 147 gp120/gp41 sequences, obtained from the Los Alamos HIV sequence database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index), by using Mascot (version 2.5.0; Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom). The peak list was extracted from raw files using the MassMatrix conversion tool. Mascot generic format (MGF) files were searched by specifying the following parameters: (i) enzyme, trypsin; (ii) missed cleavage, 2; (iii) fixed modification, carbamidomethyl; (iv) variable modification, methionine oxidation, carbamyl, HexNAc, and dHexNAc; (v) peptide tolerance, 0.8 Da; and (vi) MS-MS tolerance, 0.4 Da. Peptides identified from the Mascot search were manually validated from MS-MS data to ensure that major fragmentation ions (b and y ions) were observed, especially for peptides generated from PNGase F-treated samples that contain N-to-D conversions.

RESULTS

HIV-1 JR-FL envelope glycoproteins.

Three HIV-1 Envs based on the neutralization-resistant clade B primary isolate HIV-1 JR-FL, including two detergent-solubilized, membrane-anchored trimers and soluble gp140, were produced in CHO cells and were used for this study. The membrane-anchored JR-FL Envs are designated Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808, while the soluble gp140 Env is designated soluble gp140ΔCF. According to the standard numbering of the reference strain, HXB2, the Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 membrane-anchored JR-FL Env trimer constructs contain two serine substitutions at the proteolytic cleavage site (residues 508 and 511) (32, 33). Amino acid residues 712 to 856 and 808 to 856 of the cytoplasmic tail were truncated for the Env(−)Δ712 glycoprotein and the Env(−)Δ808 glycoprotein, respectively, to improve Env expression. Both membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Envs retain the complete ectodomain and the membrane-spanning domain. The purified Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 glycoproteins exhibited gel filtration profiles consistent with that of a trimer (data not shown). Sequence modification of the soluble HIV-1 JR-FL Env soluble gp140ΔCF construct includes the removal of the proteolytic cleavage site (C; residues 510 to 511) and the fusion peptide of gp41 (F; residues 512 to 527) (29, 34, 35). In an effort to ensure that the differences in glycosylation profiles were not due to sample preparation or to experimental variations, the data presented in this study were obtained from samples that were digested and analyzed at least three times using the same batch. Batch-to-batch variation in glycosylation profiles was evaluated using Env(−)Δ712 produced from two different batches.

Site-specific glycosylation analysis of HIV-1 JR-FL Envs.

The HIV-1 JR-FL Env contains 27 potential N-linked glycosylation (PNG) sites, as shown in Fig. 1 (red). We have identified two potential O-linked sites (purple) on the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs. The O-linked modifications occur at threonines located near the gp120 C terminus and the gp41 disulfide loop. The approach for elucidating the glycosylation profiles at each potential N- and O-linked site was based on an integrated glycopeptide-based mass analysis workflow that included sample aliquots of the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs that were fully and partially deglycosylated prior to proteolytic digestion (36, 37). Glycopeptides generated from in-solution proteolytic digests of both untreated and glycosidase-treated HIV-1 JR-FL Env samples were subsequently analyzed by LC-MS and MS-MS using a combination of CID and ETD. Glycopeptide compositions were elucidated by the GlycoPep DB, GlycoMod, and Mascot software analysis tools, as described in Materials and Methods.

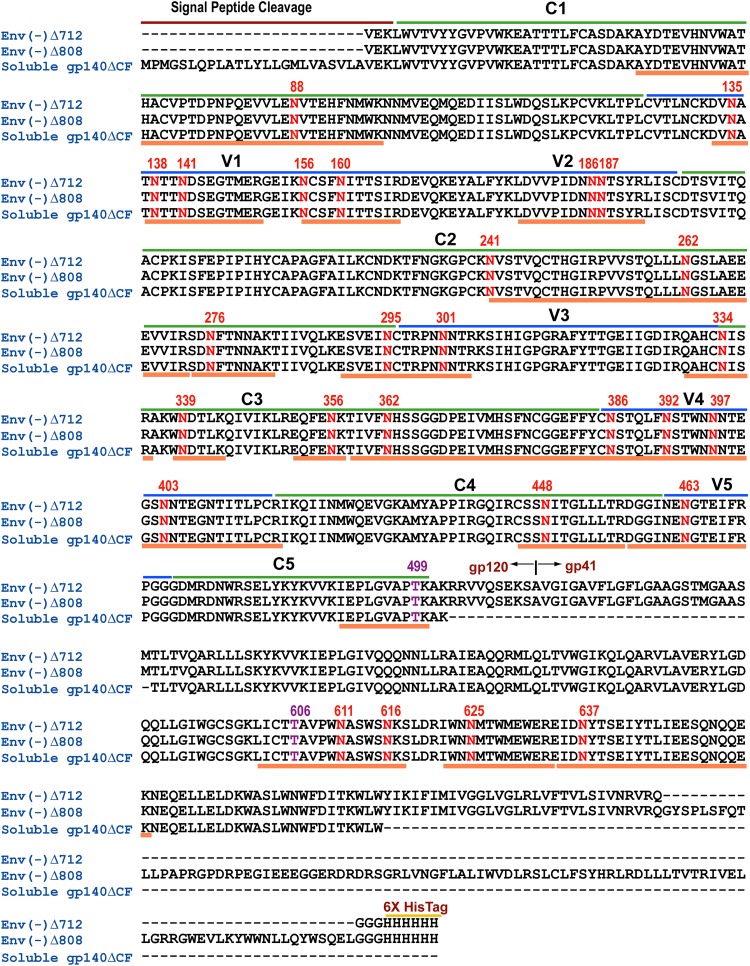

FIG 1.

Protein sequences of the HIV-1 JR-FL membrane-anchored Envs [Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808] and soluble gp140ΔCF, showing locations of conserved (C1 to C5) (green lines) and variable (V1 to V5) (blue lines) regions, potential N- and O-linked glycosylation sites (red and purple numbers, respectively), and the tryptic peptide map (orange lines beneath sequences). Sequence positions were standardized using the HIV-1 reference strain HXB2.

In silico trypsin digestion of HIV-1 JR-FL Env yields 17 peptides containing the 27 potential N-linked and 2 potential O-linked sites. The theoretical tryptic peptide map containing potential N- and O-linked glycosylation sites includes 11 peptides containing one potential glycosylation site, 4 peptides containing two potential glycosylation sites, 2 peptides containing three potential glycosylation sites, and 1 peptide containing five potential glycosylation sites (Fig. 1). In an effort to achieve full glycosylation coverage and to characterize the glycan motif at each site, we integrated a two-protease digestion strategy, as decribed in Materials and Methods, in addition to using trypsin alone. We used chymotrypsin to complement trypsin to access potential glycosylation sites in tryptic peptides bearing multiple sites. With the combination of trypsin and chymotrypsin, we obtained full glycosylation coverage representing all 27 potential N-linked sites and expanded the site-specific glycan characterization of Env regions that contained tryptic peptides bearing multiple glycosylation sites; this was particularly important for the tryptic peptide bearing five potential glycosylation sites located in the gp120 V4 region. In addition, the use of trypsin-chymotrypsin digestion provided secondary validation of many of the identifications made on the basis of the digestion with trypsin alone, due to the redundant coverage of the same regions of Env.

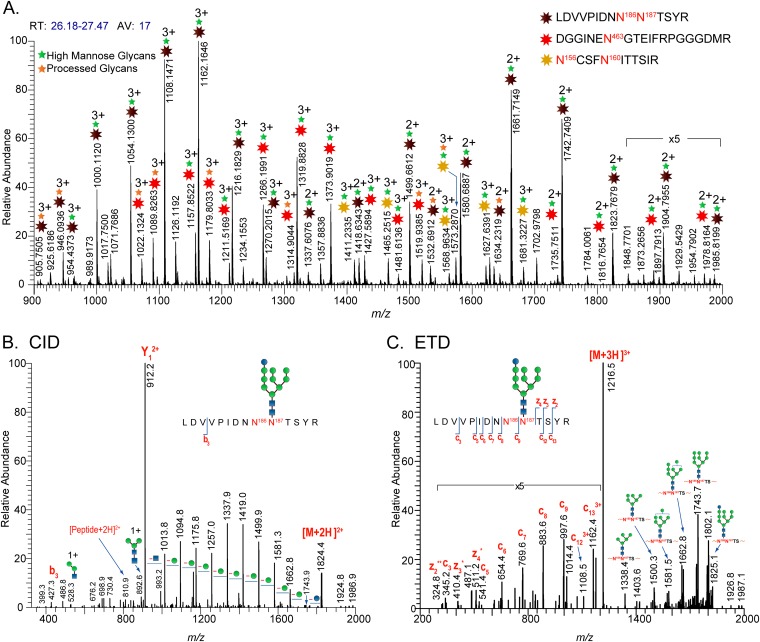

The glycan profiles of the glycopeptides generated from the proteolytic digests of the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs were deduced from both MS and MS-MS data obtained from a glycopeptide-rich region extracted from a time segment of the total-ion chromatogram (TIC). As an example, putative glycopeptides in the high-resolution mass spectra extracted from a segment of the TIC were identified from cluster peaks whose mass difference corresponds to the masses of monosaccharide units (hexose, HexNAc, fucose) (Fig. 2A). The glycan and peptide portions of a glycopeptide peak in question were elucidated and verified from fragment ion information obtained in CID and ETD data. Figure 2B and C show representative CID and ETD data used to assign the glycopeptide peak at m/z 1,216 (3+). From the glycosidic bond cleavage observed in the CID spectrum, the glycan component of the peak consists of 10 hexose and 2 HexNAc units (Fig. 2B). The peptide portion of this high-mannose glycopeptide was inferred from the Y1 ion observed at m/z 912.2 (2+). This Y1 ion corresponds to the peptide LDVVPIDNN186N187TSYR, located in the gp120 V2 region. Additional fragment information obtained from the peptide backbone cleavages observed in the ETD spectrum further confirms the peptide sequence and site utilization (Fig. 2C). Using CID and ETD data acquired from this glycopeptide-rich region and the software analysis tool GlycoPep DB (26), three sets of glycopeptides were identified in the high-resolution mass spectrum shown in Fig. 2A. Overall, full coverage for all 27 potential N-linked glycosylation sites was obtained, and O-glycosylation profiles on T499 and T606 were elucidated on all HIV-1 JR-FL Env samples.

FIG 2.

High-resolution and tandem MS data of membrane-anchored Env(−)Δ712. (A) Representative high-resolution MS data of a tryptic digest of the CHO cell-derived membrane-anchored Env(−)Δ712 glycoprotein. The mass spectrum averaged within 26.18 to 27.47 min shows the elution of four glycopeptide species. Starbursts in the MS data denote glycopeptide peaks. The glycan composition of each glycopeptide peak observed in the mass spectra was verified from CID and ETD data. (B) CID data of a high-mannose glycopeptide with the peptide portion, LDVVPIDNN186N187TSYR, showing glycosidic cleavages. (C) ETD data of the same glycopeptide showing the peptide backbone cleavages.

Glycan heterogeneity of HIV-1 JR-FL Envs.

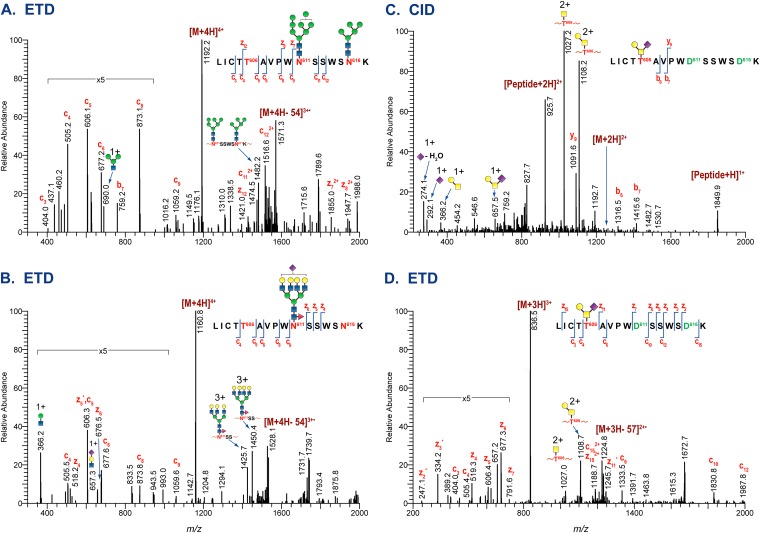

All three HIV-1 JR-FL Envs displayed extensive site-to-site glycan heterogeneity. The number of glycoforms identified ranges from 3 to 79 at each potential N-glycosylation site, and at least 3 O-linked glycans per site were identified (see Tables S1, S2, and S3 in the supplemental material). As an example, the glycan heterogeneity observed for a glycopeptide containing three potential glycosylation sites is illustrated in Fig. 3. Figure 3A to D show the representative ETD and CID data used to identify the different glycans observed for the tryptic glycopeptide containing the peptide portion LICTT606AVPWN611ASWSN625K, two potential N-linked glycosylation sites at N611 and N625, and one O-linked glycosylation site at T606. Tandem MS analyses show that both N-linked sites at N611 and N625 were modified with high-mannose glycans when fully glycosylated (Fig. 3A) and with complex-type glycan when partially glycosylated (Fig. 3B). ETD analysis of the quadruply charged glycopeptide at m/z 1,160 shown in Fig. 3B provided sufficient fragment ion information to establish that N611 was modified with a fucosylated and sialylated tetra-antennary complex-type glycan.

FIG 3.

Tandem MS data of a glycopeptide in the gp41 region of HIV-1 JR-FL Env. Shown are representative tandem MS data of the glycopeptide with the peptide portion, LICTT606AVPWN611SSWSN616K, illustrating the different types of glycans attached on each site. (A) ETD data of the glycopeptide with high-mannose glycans. (B) ETD data of the same glycopeptide with complex-type glycan. (C and D) CID and ETD data of the deglycosylated glycopeptide showing an O-linked glycan attached at T606.

In addition to the N-linked glycans, we identified an O-linked modification at T606 on the same glycopeptide for the first time. The combination of two sets of glycans on the same glycopeptide poses a unique challenge in the interpretation of MS data due to the proximity of the O-glycosylation to the N-linked sites and the smaller size of O-linked glycans. To address this challenge, Env samples can be fully deglycosylated with PNGase F to remove the N-linked modifications, followed by trypsin digestion, or directly digested with the combination of trypsin-chymotrypsin. LC-MS and MS-MS analysis of tryptic digests of PNGase F-treated Env samples indeed confirmed the identification of O-linked modified threonine. Glycosidic and peptide backbone cleavages from the representative CID (Fig. 3C) and ETD (Fig. 3D) spectra, respectively, established that T606 on the N-deglycosylated peptide was modified with core-1 type O-linked glycan. This assignment was further confirmed with Env samples generated from trypsin-chymotrypsin digests, in which O-linked modifications in the trypsin-chymotrypsin-derived peptides, ICTT606AVPW and LICTT606AVPW, were identified. Overall, we identified two O-linked modified threonine residues, located near the gp120 C terminus and the gp41 disulfide loop, in the HIV-1 JR-FL membrane-anchored Env trimers and soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein.

Comparison of the glycan profile among HIV-1 JR-FL Envs.

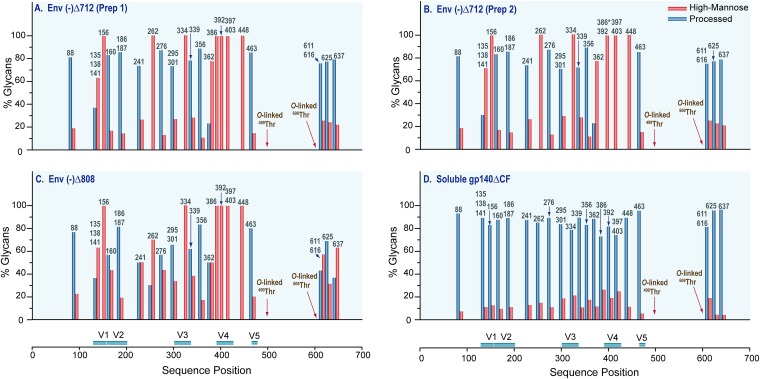

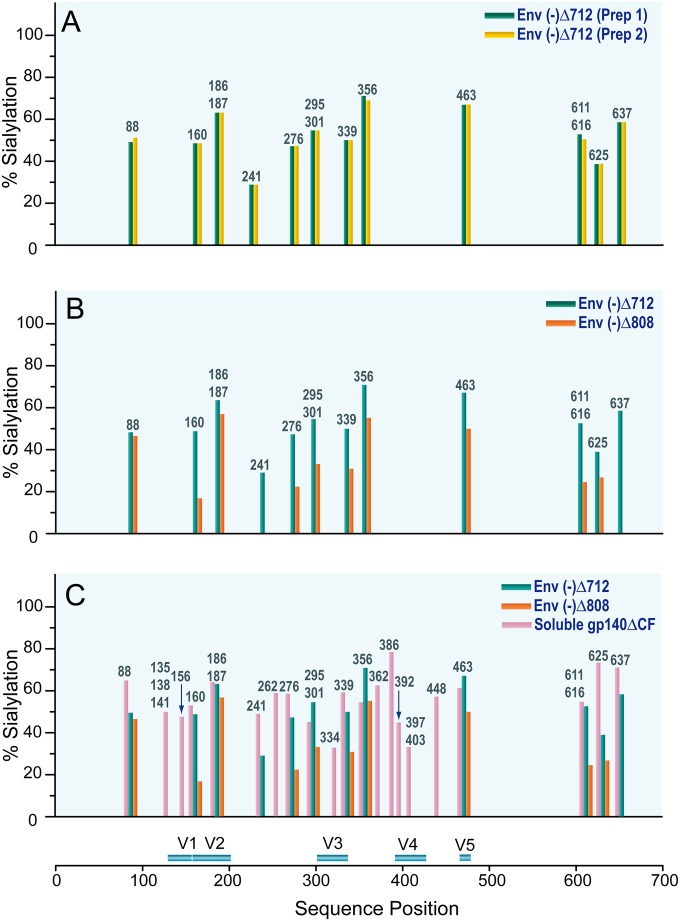

A total of ∼500 distinct glycans representing the 27 N-linked and 2 O-linked potential glycosylation sites per HIV-1 JR-FL Env sample were identified, as reported fully in Tables S1, S2, and S3 in the supplemental material. Each glycopeptide containing N-linked site displayed extensive glycan heterogeneity, including a single HexNAc, high-mannose glycans, hybrid-type glycans, and complex-type glycans consisting of a mixture of bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary structures with or without fucosylation and with varying degrees of sialylation. The glycopeptides with O-linked sites were modified with core-1 and core-2 type O-linked glycans. The glycan profile for each HIV-1 JR-FL Env was determined by sorting the glycan compositions elucidated for each glycopeptide into two groups, high-mannose and processed glycans (hybrid- and complex-type glycans), using the criteria employed in our previous studies (29, 31). The glycan profile for each glycopeptide containing a single or multiple glycosylation site(s) is represented in Fig. 4 by a pair of bars labeled with the sequence position. The overall glycan profiles of (i) two membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env(−)Δ712 glycoproteins purified on different days (Fig. 4A and B), (ii) the membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL trimer Env(−)Δ808 (Fig. 4C), and (iii) the HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein (Fig. 4D) are shown. The degrees of sialylation of these Env variants are compared in Fig. 5. The percentage of sialylation for each glycopeptide was determined by calculating the ratio of the sum of the sialylated glycopeptides to the total number of processed glycans and multiplying by 100. It is evident that each unique HIV-1 JR-FL Env variant displays a distinct glycan profile. The glycan variability observed for the HIV-1 JR-FL Env glycoproteins and shown in the bar graphs in Fig. 4 and 5 is described in the following sections.

FIG 4.

Glycan profiles of HIV-1 JR-FL Env glycoproteins. (A to C) Bar graphs show the glycan profile at each identified glycosylation site of the HIV-1 JR-FL membrane-anchored Env Env(−)Δ712 (A), a different batch of Env(−)Δ712 (B), and Env(−)Δ808 (C). (D) Glycan profile of the soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein. Glycans were broadly categorized into two classes, high-mannose (red bars) and processed (blue bars) glycans, and the glycan composition of each glycopeptide is expressed as a percentage. Glycan compositions at sites marked with a star were determined from Endo H-treated samples.

FIG 5.

Degrees of sialylation of HIV-1 JR-FL Env glycoproteins. Bar graphs show comparisons of the degrees of sialylation of preparations of membrane-anchored Env(−)Δ712 glycoprotein produced on different days (A), membrane-anchored Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 glycoproteins (B), and membrane-anchored Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 and soluble gp140ΔCF (C). The percentage of sialylation for each site was determined by the sum of sialylated glycopeptides divided by the total number of processed glycopeptides, multiplied by 100.

Glycan profiles of membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL trimers from two different batches.

As a measure of the reproducibility of the glycosylation profiles in terms of glycan composition for each glycopeptide, the glycan profiles of preparations of the membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env Env(−)Δ712, produced from two different batches at two different concentrations, were examined and compared. The bar graphs showing the N-linked glycan profile of the membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env Env(−)Δ712 produced from each batch indicate very good reproducibility (Fig. 4A and B). Close examination of the O-linked glycans reveals no difference in the number or type of O-linked glycans detected in the two batches (Table 1). Additionally, the sialylation of these two proteins was remarkably consistent, as shown in Fig. 5A. These results suggest that the differential glycan profiles reported in this study reflect the glycan variability between distinct HIV-1 JR-FL Envs and are not related to sample processing or the batch of the proteins used for analysis.

TABLE 1.

Observed O-linked glycosylation

| Peptide | O-Linked glycan | Observationa in: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env(−)Δ712 |

Env(−)Δ808 | Soluble gp140ΔCF | |||

| Prep 1 | Prep 2 | ||||

| IEPLGVAPT499KAK | HexNAc | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1[NeuAc]1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1[NeuAc]2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| LICTT606AVPWD611ASWSD625K or ICTT606AVPW/LICTT606AVPW | HexNAc | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1 | ND | ND | ND | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[NeuAc]1 | ND | ND | ND | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1[NeuAc]1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]1[NeuAc]2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [Hex]1[HexNAc]2[NeuAc]1 | ND | ND | ND | ✓ | |

| [Hex]2[HexNAc]2[NeuAc]1 | ND | ND | ND | ✓ | |

| [Hex]2[HexNAc]2[NeuAc]2 | ND | ND | ND | ✓ | |

✓, the O-glycan was observed; ND, not detected.

Glycan profiles of membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL trimers with different cytoplasmic tail lengths.

Having established the reproducibility of our measurements, we compared the N- and O-linked glycan profiles of membrane-anchored trimers differing in the lengths of their cytoplasmic tails. The Env(−)Δ712 glycoprotein lacks the cytoplasmic tail, whereas the Env(−)Δ808 glycoprotein contains all the elements of the cytoplasmic tail that have been reported to contribute to the conformation of the Env ectodomain and to modulate Env transitions to fusion-active states (25, 38, 39). With regard to N-glycosylation, Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 displayed similar ranges of N-linked glycans (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). The overall N-glycan profiles generated from 21 glycopeptides bearing the 27 N-linked sites on both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 are shown in Fig. 4A and C. Notable features of the data are as follows. First, the N-glycan profiles of both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 consist of high-mannose and processed glycans. The high-mannose structures for both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 contain as many as 12 hexose units, whereas the processed glycans are predominantly complex-type structures. Second, six glycopeptides bearing seven N-linked sites (N156, N334, N386, N392, N397, N403, and N448) in both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 are populated exclusively with high-mannose glycans. While Env(−)Δ712 has one more site with exclusively high-mannose glycans than Env(−)Δ808 (N262), Env(−)Δ808 has a higher content of high-mannose glycans overall than Env(−)Δ712. Third, the complex-type glycans consist mostly of multiantennary complex-type glycan structures that display variability in sialic acid content. The bar graph in Fig. 5B depicting the difference in the degree of sialylation between the two proteins shows that Env(−)Δ712 has a higher sialic acid content than Env(−)Δ808.

With respect to O-linked glycosylation, the two potential O-linked sites at T499 and T606 were both modified in the membrane-anchored trimers. All O-linked sites utilized in both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 were modified with a simple set of core-1 type structures ranging from a single HexNAc to disialylated O-linked species, as shown in Table 1.

Glycan profiles of membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env trimers compared with that of the HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein.

Next, we examined whether the form, i.e., membrane anchored or soluble, of the HIV-1 JR-FL Env influences N- and O-glycan profiles. Figure 4D shows a bar graph reflecting the overall N-glycan profile of the HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF expressed in CHO cells. The 27 potential N-glycosylation sites of this soluble gp140 glycoprotein were populated predominantly with processed glycans consisting of hybrid-type glycans and a diverse mixture of bi-, tri-, tetra-, and penta-antennary complex-type glycan structures with or without fucosylation and with various degrees of sialylation (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). This profile is essentially identical to a profile reported previously for the HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein expressed in 293T cells (29). The glycan profile of the soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein is completely different from the N-glycan profiles of the membrane-anchored trimers, Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808, where 9 of the 21 glycopeptides are populated predominantly with high-mannose glycans. Glycosylation sites with mostly processed glycans in the soluble gp140ΔCF all contained sialic acid (Fig. 5C). When these sites were compared among gp140ΔCF, Env(−)Δ712, and Env(−)Δ808, site-to-site variation in the degree of sialylation was observed; however, the sialic acid content of the secreted gp140ΔCF protein most resembled that of Env(−)Δ712.

The membrane-anchored and soluble JR-FL Envs displayed similar core-1 type O-glycan profiles at site T499, as shown in Table 1. Four core-1 type O-glycans were observed at T499 for all of the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs. The O-glycan profiles displayed significant differences at gp41 site T606, located close to two potential N-linked glycosylation sites. At T606, a total of eight O-glycans consisting of core-1 and core-2 type O-glycans were identified in the soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein, whereas a simple set of core-1 type O-glycans was identified in both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 (Table 1).

Site occupancy of HIV-1 JR-FL Envs.

As with the HIV-1 Envs we have analyzed previously (29, 31, 36, 37), not all potential glycosylation sites in the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs are fully utilized. The extent of glycosylation was determined from the LC-MS and MS-MS analysis of Endo H- and PNGase F-treated HIV-1 JR-FL Envs, as described previously (36, 37). Data acquired from MS analysis were used to search a custom HIV-1 database by using Mascot as described in Materials and Methods. Table 2 shows the extents of glycosylation for the 27 potential N-linked and 2 O-linked glycosylation sites of HIV-1 JR-FL soluble gp140ΔCF, Env(−)Δ808, and the two different batches of Env(−)Δ712. In agreement with the results obtained from the analysis of glycan profiles, the results from the two different batches of the Env(−)Δ712 glycoprotein clearly show that differences in site occupancy were not due to variation between batches. A striking observation is that the extent of glycosylation can be affected by the presence of Env cytoplasmic tail sequences. Env(−)Δ808, which retains a cytoplasmic tail and is the longest of the three glycoproteins analyzed, has more fully utilized N-linked sites than Env(−)Δ712, which is identical to Env(−)Δ808 except for the absence of the cytoplasmic tail. The least glycosylated protein, soluble gp140ΔCF, is not membrane anchored and lacks a transmembrane region as well as a cytoplasmic tail.

TABLE 2.

Glycosylation site occupancy

| Type of glycosylation and peptide | No. of PNG sites | No. of glycosylation sites occupied |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env(−)Δ712 |

Env(−)Δ808 | Soluble gp140ΔCF | |||

| Prep 1 | Prep 2 | ||||

| N-Linked glycosylation | |||||

| AYDTEVHNVWATHACVPTDPNPQEVVLEN88VTEHFNMWK | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| DVN135ATN138TTN141DSEGTMER | 3 | 0, 1, and 2 | 0, 1, and 2 | 1 and 2 | 0, 1, and 2 |

| N156CSF/GEIK N156CSF | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| N160ITTSIR/N160ITTSIRDEVQK | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| LDVVPIDNN186N187TSYR/LDVVPIDNN186N187TSY | 2 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| N241VSTVQCTH/N241VSTVQCTHGIR | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| LLN262GSLAEEEVVIR/GIRPVVSTQLLLN262GSLAEEEVVIR | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| SDN276FTNNAK | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| ESVEIN295CTRPNN301NTR | 2 | 0, 1, and 2 | 0, 1, and 2 | 1 and 2 | 1 and 2 |

| QAHCN334ISR | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| WN339DTLK | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| EQFEN356K/LREQFEN356K | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| TIVFN362HSSGGDPEIVMH/TIVFN362H/N362HSSGGDPEIVMH | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| CN386STQLF/Y CN386STQLF | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| N392STW/F N392STW | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| NN397NTEGSN403NTEGNTITLPCR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0, 1, and 2 |

| CSSN448ITGLLLTR/CSSN448ITGL | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| DGGINEN462GTEIFRPGGGDMR/DGGINEN462GTEIF | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| LICTTAVPWN611ASWSN616K | 2 | 0, 1, and 2 | 0, 1, and 2 | 1 and 2 | 0, 1, and 2 |

| IWNN625MTWMEWER | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| EIDN637YTSEIYTLIEESQNQQEK | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 1 | 0 and 1 |

| Total | 27 | 5–25 | 5–25 | 13–25 | 4–25 |

| O-Linked glycosylation | |||||

| IEPLGVAPT499KAK/IEPLGVAPT499K | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| LICTT606AVPWD611ASWSD616K/LICTT606AVPW/ICTT606AVPW | 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 | 0 and 1 |

| Total | 2 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–2 |

DISCUSSION

The continuing effort to produce Envs that closely mimic the native functional Env spike has driven the development of next-generation Env-based vaccines. To date, different forms of Env, including membrane-anchored trimers, a number of iterations of the soluble versions of gp140 glycoproteins, and Envs from viral preparations, are being used in immunogenicity, biophysical, and structural studies to identify potential Env candidates that would induce a broad and potent neutralizing antibody response against HIV-1 (21, 32, 33, 35, 40–44). Given that the extensive glycosylation of the Envs is one of the important correlates of Env immunogenicity and antigenicity, it is crucial to determine the glycosylation profiles of native HIV-1 Envs and to identify the glycosylation motifs that are immunologically significant.

In this study, MS-based glycosylation analysis was used to address whether Env glycosylation is dependent on the Env form, i.e., membrane anchored or soluble. We characterized and identified the differences between the N- and O-linked glycosylation profiles of two membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Env trimers, Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808, and that of the soluble version of HIV-1 JR-FL Env, gp140ΔCF. Clearly, Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 displayed N- and O-glycosylation profiles distinct from that of soluble gp140ΔCF. Specifically, both Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 have more N-linked sites populated with high-mannose glycans, which include high-mannose structures bearing 10 to 12 hexoses. When Env is expressed in a more truncated, soluble form, the glycans may be more accessible to glycan-processing enzymes, resulting in a more heavily processed glycosylation profile. These results indicate that glycans of the soluble gp140ΔCF oligomer do not closely mimic those of membrane-bound JR-FL Env, since they are processed differently in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. Our observation that membrane-associated Envs display significantly more high-mannose glycans than a soluble Env is consistent with previous studies of Env isolated from virions, which exhibited a preponderance of high-mannose carbohydrates (21, 22, 45). The fact that Env complexes on the cell surface serve as the direct source of virion Env spikes explains this consistency in glycosylation profiles. Because proteolytic cleavage is a very late event in Env biosynthesis, the glycosylation profile of our cleavage-negative membrane Envs is expected to resemble closely those of the mature cell surface and virion Envs.

Our studies extend previous analyses and provide new insight into membrane-anchored glycosylation profiles of Env because the glycoform profile can be elucidated at each glycosylation site. A benefit of glycopeptide analysis on these proteins, compared to glycan analyses, is the ability to track minority glycoform populations. When aggregate glycan analysis was conducted on virion Env, sialylated glycoforms were not detected (21, 22). Glycopeptide analysis provides increased depth in glycoform profiling because low-abundance glycoforms, which are present at only a few glycosylation sites, can be detected, even when high-mannose glycans dominate most of the glycosylation sites. Glycopeptide analysis of Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 shows multiple glycosylation sites bearing processed glycans that contain significant levels of sialic acid. The presence of sialylated glycans can have a profound effect on Env antigenicity and immunogenicity, since sialic acids are known to modulate the host immune response, acting as recognition elements for lectins and as biological masks (46, 47). Additionally, some broadly neutralizing antibodies recognize an epitope that includes sialic acid at N156 (15).

Comparison of Env sialic acid contents in this study showed that Env(−)Δ808 contained less sialic acid than Env(−)Δ712. Apparently, as has been suggested by other studies (25, 38, 39), the cytoplasmic tail can influence the conformation of the HIV-1 Env ectodomain, resulting in differences in the processing of high-mannose glycans in the Golgi apparatus. This difference could be significant for vaccine developers, because a low sialic content on gp120 has been shown to improve immunogenicity (12). Both membrane-bound Env trimers displayed less sialic acid than the soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein. This trend suggests that perhaps membrane-anchored trimers are less sialylated than soluble, truncated versions of the same protein.

While global differences in the glycan processing of these Env variants were observed, these data sets are also useful for comparing glycosylation profiles at specific glycosylation sites of interest, such as those that interact with broadly neutralizing antibodies. For example, recent work by Amin et al. (15) and others (48) has shown that the broadly neutralizing antibody PG16 prefers a high-mannose glycan at N160 and a sialylated glycoform at N156. This antibody is known to prefer trimeric forms of Env, but it does not bind to trimeric HIV-1 JR-FL because of a glutamic acid residue at position 168 in the gp120 V2 region (19). The glycosylation analysis data presented here help to explain why the binding of these antibodies is not optimal, even when residue 168 in the JR-FL Env is altered (32). The HIV-1 JR-FL membrane Envs contain a high-mannose (nonsialylated) glycosylation site at N156, and N160 is modified by a large number of processed glycans. Thus, even though the HIV-1 JR-FL Env, like other cell surface HIV-1 Envs, contains predominantly high-mannose glycans, the glycosylation site-specific data show that these high-mannose glycans are not universally present across all the glycosylation sites. The processed glycans present at N160 likely reduce the levels of Env-binding antibodies such as PG16, which prefer a high-mannose glycan at this site.

In addition to studying the N-linked glycoforms on these Envs, we identified two O-linked modifications on threonine residues near the gp120 C terminus (T499) and the gp41 disulfide loop (T606). The O-glycan at T499 is a common modification observed in HIV-1 gp120 and gp140 Env glycoproteins analyzed previously (37, 49, 50), whereas the O-linked modification on T606 was observed for the first time in this study. Although the addition of O-linked glycans is not absolutely required for the receptor-binding and membrane-fusing functions of HIV-1 Env (51), the very high level of conservation of T606 among primate immunodeficiency viruses (52) supports a potentially important role, perhaps in immune evasion, for this O-glycan. For example, the presence of this newly identified glycoform may impact the binding of antibodies to the gp41 subunit of Env. Prior studies have shown that when the N-linked glycans adjacent to this site, at N611 and N616, are removed, the recognition of gp140 by two neutralizing antibodies against the gp41 membrane-proximal external region (MPER), 2F5 and 4E10, increases (53). While it is not known at this time whether this newly identified O-linked glycan impacts the binding of anti-MPER antibodies, structural studies of this region and vaccine design strategies that target MPER epitopes should account for this newly discovered feature of Env.

Because O-linked glycans are added late in glycoprotein biosynthesis, in the Golgi apparatus (54, 55), our observation that O-linked glycans are added to T499 and T606 indicates that these amino acid residues are exposed on the uncleaved membrane-anchored and soluble HIV-1 JR-FL Env trimers. In a recently published crystal structure of a soluble gp140 SOSIP.664 trimer from HIV-1 BG505 (56), T499 is solvent exposed, but T606 is not. Thus, the structures of the membrane and soluble HIV-1 JR-FL Env trimers that we studied here must differ from that of the soluble gp140 SOSIP.664 glycoprotein, at least in the vicinity of T606 in gp41. Insights into the differences between native HIV-1 Env trimers and glycoproteins such as soluble gp140 SOSIP.664 that are being considered for use as immunogens may be helpful in improving vaccine candidates.

A common glycosylation feature of the recombinant soluble HIV-1 Envs we have analyzed to date is that a given glycosylation site may be fully occupied, partially occupied, or not utilized at all (29, 31, 36, 37, 57). Such variability in glycosylation site utilization can directly influence the immunogenicity and antigenicity of Envs. Indeed studies have shown that the absence and/or removal of glycans increases antibody neutralization sensitivities (58–62). We have demonstrated recently that soluble transmitted/founder HIV-1 soluble gp140s expressed in different cell lines exhibit relatively similar site utilization (37). In this study, we identified the length of the cytoplasmic tail as a variable that can influence glycosylation site occupancy. The two membrane-anchored HIV-1 JR-FL Envs with different C termini show significant differences in their degrees of site occupancy. There are twice as many fully utilized sites in CHO-derived Env(−)Δ808 than in Env(−)Δ712. In contrast, Env(−)Δ712 and the soluble gp140ΔCF display similar levels of glycosylation site utilization. Env(−)Δ808 contains almost 100 amino acids in the cytoplasmic tail that are not present in the Env(−)Δ712 or soluble gp140ΔCF glycoprotein. It is not clear at this point how this longer protein sequence influences glycosylation site occupancy in the Env ectodomain, since the N-terminal glycosylation sites can potentially be occupied prior to translation of the C-terminal region. However, for a heavily glycosylated protein such as Env, the additional time on the ribosome associated with translation of a longer protein may allow more complete engagement of all the sequons by the glycosylation machinery. More investigation into this issue is warranted. Whatever the explanation, the trend we observe is an interesting and potentially significant one: the Env that is most similar (in terms of sequence) to native Env, Env(−)Δ808, shows a significantly higher degree of occupied glycosylation sites than more-truncated versions of the same protein.

Finally, various attempts have been made to use kifunensine or production in GnT1-negative cells to give soluble gp140 glycoproteins a glycan profile richer in mannose residues and lacking complex carbohydrates. These approaches can restore some epitopes involving high-mannose glycans on gp120. However, our results suggest that naturally produced HIV-1 Env has a mixture of high-mannose and processed carbohydrates that is highly site dependent. This native glycosylation profile cannot be reproduced on the soluble gp140 glycoproteins simply by inhibition of a particular glycosidase. Immunogens that derive from the membrane-anchored Envs should more closely mimic the glycan profile found on infectious virions.

In conclusion, we evaluated and compared the glycosylation profiles of membrane-anchored and soluble Envs derived from the primary, neutralization-resistant HIV-1 JR-FL isolate using CID/ETD-based glycopeptide analysis. Using this approach, we achieved full glycosylation coverage of all 27 potential N-glycosylation sites and characterized the O-linked glycosylation profiles of Envs of different lengths. In general, the HIV-1 JR-FL Envs analyzed in this study displayed distinct N- and O-glycosylation profiles with extensive glycan heterogeneity at any given site. The N-linked glycosylation profiles for different JR-FL Env forms differed considerably, particularly between membrane-anchored Envs and soluble gp140. Specifically, the membrane-anchored Envs, Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808, contained more high-mannose glycans than the soluble gp140ΔCF: the high proportion of processed glycans on the soluble gp140 is consistent with prior glycan-based analyses of similar proteins (21, 22). We also determined that Env(−)Δ712 and Env(−)Δ808 exhibited some specific differences in their N-glycosylation profiles. Relative to Env(−)Δ712, Env(−)Δ808 has higher site occupancy, more sites with high-mannose glycans, and a lower sialic acid content, suggesting that the cytoplasmic tail can influence Env glycosylation.

We identified two O-linked glycosylation sites, one involving T606 in the gp41 subunit that has not been previously described. In general, site-to-site variation in O-linked modification was observed for the three Envs. Defining the differences in N- and O-linked glycosylation features across Env forms could provide critical information needed to understand the immunogenicity and antigenicity of Env vaccine candidates. It will also be of interest to determine whether any differences in the Env glycosylation profile dependent on the virus-producing cell influence the biological properties of HIV-1. More studies on additional Env sequences will be necessary to understand the range of differences in glycan type and occupancy associated with diverse strains of HIV-1 replicating in various host cell types.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM103547 and AI094797 to H. Desaire, GM095639 to J. C. Kappes, and AI024755 and AI100645 to J. Sodroski. The work was also supported by the Virology, Genetic Sequencing and Flow Cytometry Cores of the UAB Center for AIDS Research (NIH, P30 AI27767).

We gratefully acknowledge Barton F. Haynes for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00628-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. 2013. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic 2013. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barré-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vézinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L. 1983. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, Shearer GM, Kaplan M, Haynes BF, Palker TJ, Redfield R, Oleske J, Safai B, White G, Foster P, Markham PD. 1984. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science 224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoxie JA. 2010. Toward an antibody-based HIV-1 vaccine. Annu Rev Med 61:135–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042507.164323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. 1990. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem 265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Luo LZ, Rasool N, Kang CY. 1993. Glycosylation is necessary for the correct folding of human immunodeficiency virus-gp120 in CD4 binding. J Virol 67:584–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenouillet E, Jones IM. 1995. The glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein (gp41) is important for the efficient intracellular transport of the envelope precursor gp160. J Gen Virol 76(Part 6):1509–1514. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-6-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reitter JN, Means RE, Desrosiers RC. 1998. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med 4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCaffrey RA, Saunders C, Hensel M, Stamatatos L. 2004. N-linked glycosylation of the V3 loop and the immunologically silent face of gp120 protects human immunodeficiency virus type 1 SF162 from neutralization by anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 antibodies. J Virol 78:3279–3295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3279-3295.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, Sweet RW, Robinson J, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski JG. 1998. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong L, Sheppard NC, Stewart-Jones GBE, Robson CL, Chen H, Xu X, Krashias G, Bonomelli C, Scanlan CN, Kwong PD, Jeffs SA, Jones IM, Sattentau QJ. 2010. Expression-system-dependent modulation of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein antigenicity and immunogenicity. J Mol Biol 403:131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raska M, Takahashi K, Czernekova L, Zachova K, Hall S, Moldoveanu Z, Elliott MC, Wilson L, Brown R, Jancova D, Barnes S, Vrbkova J, Tomana M, Smith PD, Mestecky J, Renfrow MB, Novak J. 2010. Glycosylation patterns of HIV-1 gp120 depend on the type of expressing cells and affect antibody recognition. J Biol Chem 285:20860–20869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Wormald MR, Ollmann SE, Stanfield R, Wilson IA, Katinger H, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR. 2002. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of α1→2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J Virol 76:7306–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7306-7321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin MN, McLellan JS, Huang W, Orwenyo J, Burton DR, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Wang LX. 2013. Synthetic glycopeptides reveal the glycan specificity of HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nat Chem Biol 9:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, O'Dell S, Patel N, Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Zhou T, Zhu J, Boyington JC, Chuang GY, Diwanji D, Georgiev I, Kwon YD, Lee D, Louder MK, Moquin S, Schmidt SD, Yang ZY, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Koff WC, Walker LM, Phogat S, Wyatt R, Orwenyo J, Wang LX, Arthos J, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Schief WR, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Kwong PD. 2011. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 480:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Murin CD, Julien JP, McBride R, Liu Y, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, Hoffenberg S, Caulfield M, King CR, Hua Y, Le KM, Khayat R, Deller MC, Clayton T, Tien H, Feizi T, Sanders RW, Paulson JC, Moore JP, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Ward AB, Wilson IA. 2013. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alam SM, Dennison SM, Aussedat B, Vohra Y, Park PK, Fernandez-Tejada A, Stewart S, Jaeger FH, Anasti K, Blinn JH, Kepler TB, Bonsignori M, Liao HX, Sodroski JG, Danishefsky SJ, Haynes BF. 2013. Recognition of synthetic glycopeptides by HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies and their unmutated ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:18214–18219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317855110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2009. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, Mitcham JL, Hammond PW, Olsen OA, Phung P, Fling S, Wong CH, Phogat S, Wrin T, Simek MD, Koff WC, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P. 2011. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature 477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doores KJ, Bonomelli C, Harvey DJ, Vasiljevic S, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. 2010. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006498107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonomelli C, Doores KJ, Dunlop DC, Thaney V, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. 2011. The glycan shield of HIV is predominantly oligomannose independently of production system or viral clade. PLoS One 6:e23521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hildebrandt E, Ding H, Mulky A, Dai Q, Aleksandrov AA, Bajrami B, Diego PA, Wu X, Ray M, Naren AP, Riordan JR, Yao X, DeLucas LJ, Urbatsch IL, Kappes JC. 2015. A stable human-cell system overexpressing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator recombinant protein at the cell surface. Mol Biotechnol 57:391–405. doi: 10.1007/s12033-014-9830-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urlinger S, Baron U, Thellmann M, Hasan MT, Bujard H, Hillen W. 2000. Exploring the sequence space for tetracycline-dependent transcriptional activators: novel mutations yield expanded range and sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:7963–7968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.André S, Seed B, Eberle J, Schraut W, Bultmann A, Haas J. 1998. Increased immune response elicited by DNA vaccination with a synthetic gp120 sequence with optimized codon usage. J Virol 72:1497–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Go EP, Rebecchi KR, Dalpathado DS, Bandu ML, Zhang Y, Desaire H. 2007. GlycoPep DB: a tool for glycopeptide analysis using a “Smart Search.” Anal Chem 79:1708–1713. doi: 10.1021/ac061548c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irungu J, Go EP, Dalpathado DS, Desaire H. 2007. Simplification of mass spectral analysis of acidic glycopeptides using GlycoPep ID. Anal Chem 79:3065–3074. doi: 10.1021/ac062100e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper CA, Gasteiger E, Packer NH. 2001. GlycoMod—a software tool for determining glycosylation compositions from mass spectrometric data. Proteomics 1:340–349. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Go EP, Irungu J, Zhang Y, Dalpathado DS, Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Desaire H. 2008. Glycosylation site-specific analysis of HIV envelope proteins (JR-FL and CON-S) reveals major differences in glycosylation site occupancy, glycoform profiles, and antigenic epitopes' accessibility. J Proteome Res 7:1660–1674. doi: 10.1021/pr7006957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irungu J, Go EP, Zhang Y, Dalpathado DS, Liao HX, Haynes BF, Desaire H. 2008. Comparison of HPLC/ESI-FTICR MS versus MALDI-TOF/TOF MS for glycopeptide analysis of a highly glycosylated HIV envelope glycoprotein. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 19:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Go EP, Chang Q, Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Desaire H. 2009. Glycosylation site-specific analysis of clade C HIV-1 envelope proteins. J Proteome Res 8:4231–4242. doi: 10.1021/pr9002728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao Y, Wang L, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Xiang SH, Haim H, Yang X, Sodroski J. 2012. Subunit organization of the membrane-bound HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:893–899. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao Y, Wang L, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Desormeaux A, Finzi A, Xiang SH, Sodroski JG. 2013. Molecular architecture of the uncleaved HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307382110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakrabarti BK, Kong WP, Wu BY, Yang ZY, Friborg J, Ling X, King SR, Montefiori DC, Nabel GJ. 2002. Modifications of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein enhance immunogenicity for genetic immunization. J Virol 76:5357–5368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5357-5368.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao HX, Sutherland LL, Xia SM, Brock ME, Scearce RM, Vanleeuwen S, Alam SM, McAdams M, Weaver EA, Camacho Z, Ma BJ, Li Y, Decker JM, Nabel GJ, Montefiori DC, Hahn BH, Korber BT, Gao F, Haynes BF. 2006. A group M consensus envelope glycoprotein induces antibodies that neutralize subsets of subtype B and C HIV-1 primary viruses. Virology 353:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Go EP, Hewawasam G, Liao HX, Chen H, Ping LH, Anderson JA, Hua DC, Haynes BF, Desaire H. 2011. Characterization of glycosylation profiles of HIV-1 transmitted/founder envelopes by mass spectrometry. J Virol 85:8270–8284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Go EP, Liao HX, Alam SM, Hua D, Haynes BF, Desaire H. 2013. Characterization of host-cell line specific glycosylation profiles of early transmitted/founder HIV-1 gp120 envelope proteins. J Proteome Res 12:1223–1234. doi: 10.1021/pr300870t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubay JW, Roberts SJ, Hahn BH, Hunter E. 1992. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J Virol 66:6616–6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabuzda DH, Lever A, Terwilliger E, Sodroski J. 1992. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J Virol 66:3306–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao F, Liao HX, Hahn BH, Letvin NL, Korber BT, Haynes BF. 2007. Centralized HIV-1 envelope immunogens and neutralizing antibodies. Curr HIV Res 5:572–577. doi: 10.2174/157016207782418498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iyer SP, Franti M, Krauchuk AA, Fisch DN, Ouattara AA, Roux KH, Krawiec L, Dey AK, Beddows S, Maddon PJ, Moore JP, Olson WC. 2007. Purified, proteolytically mature HIV type 1 SOSIP gp140 envelope trimers. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 23:817–828. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovacs JM, Nkolola JP, Peng H, Cheung A, Perry J, Miller CA, Seaman MS, Barouch DH, Chen B. 2012. HIV-1 envelope trimer elicits more potent neutralizing antibody responses than monomeric gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:12111–12116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204533109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders RW, Derking R, Cupo A, Julien JP, Yasmeen A, de Val N, Kim HJ, Blattner C, de la Peña AT, Korzun J, Golabek M, de Los Reyes K, Ketas TJ, van Gils MJ, King CR, Wilson IA, Ward AB, Klasse PJ, Moore JP. 2013. A next-generation cleaved, soluble HIV-1 Env trimer, BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140, expresses multiple epitopes for broadly neutralizing but not non-neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003618. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X, Lee J, Mahony EM, Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. 2002. Highly stable trimers formed by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins fused with the trimeric motif of T4 bacteriophage fibritin. J Virol 76:4634–4642. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4634-4642.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Shah P, Toghi ES, Yang S, Sun S, Ao M, Rubin A, Jackson JB, Zhang H. 2014. Glycoform analysis of recombinant and human immunodeficiency virus envelope protein gp120 via higher energy collisional dissociation and spectral-aligning strategy. Anal Chem 86:6959–6967. doi: 10.1021/ac500876p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varki A, Gagneux P. 2012. Multifarious roles of sialic acids in immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1253:16–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varki NM, Varki A. 2007. Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease. Lab Invest 87:851–857. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu B, Morales JF, O'Rourke SM, Tatsuno GP, Berman PW. 2012. Glycoform and net charge heterogeneity in gp120 immunogens used in HIV vaccine trials. PLoS One 7:e43903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stansell E, Canis K, Haslam SM, Dell A, Desrosiers RC. 2011. Simian immunodeficiency virus from the sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque is modified with O-linked carbohydrate. J Virol 85:582–595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01871-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Go EP, Hua D, Desaire H. 2014. Glycosylation and disulfide bond analysis of transiently and stably expressed clade C HIV-1 gp140 trimers in 293T cells identifies disulfide heterogeneity present in both proteins and differences in O-linked glycosylation. J Proteome Res 13:4012–4027. doi: 10.1021/pr5003643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozarsky K, Penman M, Basiripour L, Haseltine W, Sodroski J, Krieger M. 1989. Glycosylation and processing of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foley B, Leitner T, Apetrei C, Hahn B, Mizrachi I, Mullins J, Rambaut A, Wolinsky S, Korber B (ed). 2013. HIV sequence compendium 2013. LA-UR 13-26007 Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma BJ, Alam SM, Go EP, Lu X, Desaire H, Tomaras GD, Bowman C, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Santra S, Letvin NL, Kepler TB, Liao HX, Haynes BF. 2011. Envelope deglycosylation enhances antigenicity of HIV-1 gp41 epitopes for both broad neutralizing antibodies and their unmutated ancestor antibodies. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piller V, Piller F, Fukuda M. 1990. Biosynthesis of truncated O-glycans in the T cell line Jurkat. Localization of O-glycan initiation. J Biol Chem 265:9264–9271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Röttger S, White J, Wandall HH, Olivo JC, Stark A, Bennett EP, Whitehouse C, Berger EG, Clausen H, Nilsson T. 1998. Localization of three human polypeptide GalNAc-transferases in HeLa cells suggests initiation of O-linked glycosylation throughout the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Sci 111(Part 1):45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, Stewart-Jones GB, Stuckey J, Bailer RT, Joyce MG, Louder MK, Tumba N, Yang Y, Zhang B, Cohen MS, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Morris L, Munro JB, Blanchard SC, Mothes W, Connors M, Kwong PD. 2014. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature 514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pabst M, Chang M, Stadlmann J, Altmann F. 2012. Glycan profiles of the 27 N-glycosylation sites of the HIV envelope protein CN54gp140. Biol Chem 393:719–730. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Binley JM, Wyatt R, Desjardins E, Kwong PD, Hendrickson W, Moore JP, Sodroski J. 1998. Analysis of the interaction of antibodies with a conserved enzymatically deglycosylated core of the HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 14:191–198. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chackerian B, Rudensey LM, Overbaugh J. 1997. Specific N-linked and O-linked glycosylation modifications in the envelope V1 domain of simian immunodeficiency virus variants that evolve in the host alter recognition by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 71:7719–7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cole KS, Steckbeck JD, Rowles JL, Desrosiers RC, Montelaro RC. 2004. Removal of N-linked glycosylation sites in the V1 region of simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 results in redirection of B-cell responses to V3. J Virol 78:1525–1539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1525-1539.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson WE, Sanford H, Schwall L, Burton DR, Parren PW, Robinson JE, Desrosiers RC. 2003. Assorted mutations in the envelope gene of simian immunodeficiency virus lead to loss of neutralization resistance against antibodies representing a broad spectrum of specificities. J Virol 77:9993–10003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9993-10003.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez-Navio JM, Desrosiers RC. 2012. Neutralizing capacity of monoclonal antibodies that recognize peptide sequences underlying the carbohydrates on gp41 of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 86:12484–12493. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01959-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.