ABSTRACT

New efforts are under way to develop a vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) that will provide protective immunity without the potential for vaccine-associated disease enhancement such as that observed in infants following vaccination with formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine. In addition to the F fusion protein, the G attachment surface protein is a target for neutralizing antibodies and thus represents an important vaccine candidate. However, glycosylated G protein expressed in mammalian cells has been shown to induce pulmonary eosinophilia upon RSV infection in a mouse model. In the current study, we evaluated in parallel the safety and protective efficacy of the RSV A2 recombinant unglycosylated G protein ectodomain (amino acids 67 to 298) expressed in Escherichia coli (REG) and those of glycosylated G produced in mammalian cells (RMG) in a mouse RSV challenge model. Vaccination with REG generated neutralizing antibodies against RSV A2 in 7/11 BALB/c mice, while RMG did not elicit neutralizing antibodies. Total serum binding antibodies against the recombinant proteins (both REG and RMG) were measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and were found to be >10-fold higher for REG- than for RMG-vaccinated animals. Reduction of lung viral loads to undetectable levels after homologous (RSV-A2) and heterologous (RSV-B1) viral challenge was observed in 7/8 animals vaccinated with REG but not in RMG-vaccinated animals. Furthermore, enhanced lung pathology and elevated Th2 cytokines/chemokines were observed exclusively in animals vaccinated with RMG (but not in those vaccinated with REG or phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) after homologous or heterologous RSV challenge. This study suggests that bacterially produced unglycosylated G protein could be developed alone or as a component of a protective vaccine against RSV disease.

IMPORTANCE New efforts are under way to develop vaccines against RSV that will provide protective immunity without the potential for disease enhancement. The G attachment protein represents an important candidate for inclusion in an effective RSV vaccine. In the current study, we evaluated the safety and protective efficacy of the RSV A2 recombinant unglycosylated G protein ectodomain produced in E. coli (REG) and those of glycosylated G produced in mammalian cells (RMG) in a mouse RSV challenge model (strains A2 and B1). The unglycosylated G generated high protective immunity and no lung pathology, even in animals that lacked anti-RSV neutralizing antibodies prior to RSV challenge. Control of viral loads correlated with antibody binding to the G protein. In contrast, the glycosylated G protein provided poor protection and enhanced lung pathology after RSV challenge. Therefore, bacterially produced unglycosylated G protein holds promise as an economical approach to a protective vaccine against RSV.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of virus-mediated lower respiratory tract illness (LRI) in infants and children worldwide. In the United States, RSV is a major cause of morbidity, second only to influenza virus (1). For infants, more than 2% of hospitalizations are attributable to RSV infection annually (1). Although traditionally regarded as a pediatric pathogen, RSV can cause life-threatening pulmonary disease in bone marrow transplant recipients and immunocompromised patients (2, 3). In developing countries, most RSV-mediated severe disease occurs in infants younger than 2 years and results in significant infant mortality (4). Among the elderly, RSV is also a common cause of severe respiratory infections that require hospitalization (4).

Although the importance of RSV as a respiratory pathogen has been recognized for more than 50 years, no vaccine is available yet because of several problems inherent in RSV vaccine development. These barriers to development include the very young age of the target population, recurrent infections in spite of prior exposure, and a history of enhanced disease in young children who were immunized with a formaldehyde-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine in the 1960s (3, 5). Subsequent studies with samples from these children showed poor functional antibody responses with low neutralization or fusion-inhibition titers (6, 7). There was also evidence for deposition of immune complexes in the small airways (8); however, the mechanism of the FI-RSV vaccine-induced enhanced disease is poorly understood. Animal models of the FI-RSV vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (VAERD) suggested a possible combination of poor functional antibody responses and Th2-biased hypercytokine release, leading to eosinophilic infiltration in the lungs (9, 10).

RSV live-attenuated vaccines (LAV) are an attractive vaccine modality for young children. These vaccines present to the immune system many viral genes with potential protective targets, including the F and G membrane proteins. By using reverse genetics, attenuating mutations were incorporated into RSV A2 in different combinations, and this strategy has been explored extensively, with an emphasis on reaching a good balance between safety and immunogenicity (11). However, the stability of the engineered mutations is an important technical challenge (12). A recent RSV LAV candidate (rA2cp248/404/1030deltaSH) was found to be safe in infants but poorly immunogenic (13). However, new RSV LAV candidates are being evaluated.

Vaccines based on recombinant proteins in different cell substrates have been pursued as well (3, 14). Earlier, RSV F glycoprotein (PFP-2) formulated in alum was well tolerated in clinical trials but only modestly immunogenic in adults, pregnant women, and the elderly (15). A mixture of F, G, and M recombinant proteins was tested in individuals >65 years old and was found to induce >4-fold increases in serum neutralizing activity in 58% of subjects with low prevaccine titers (16). Recently, the structures of the F protective targets recognized by the monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) palivizumab and 101F were resolved, as well as the prefusion form of the F protein trimer, leading to the structure-based design of stabilized F protein vaccine candidates (17–19). The G protein was also evaluated as a vaccine candidate in preclinical studies. A nanoparticle vaccine encompassing the RSV G protein CX3C chemokine motif protected BALB/c mice from RSV challenge (20). A subunit vaccine based on the central conserved region of the G attachment surface glycoprotein was fused to the albumin-binding domain from streptococcal protein G, produced in prokaryotic cells, and formulated with an alum-based adjuvant. After promising results in murine models, challenge studies with rhesus macaques showed no reduction in viral loads, and studies with human adults showed a relatively low capacity for inducing neutralizing antibodies (21, 22). Ideally, an optimally effective RSV vaccine must protect against antigenically divergent group A and B RSV strains.

In the current study, we evaluate side by side the immunogenicity, safety, and protective capacity of a recombinant RSV G protein ectodomain (amino acids 67 to 298) vaccine produced either as an unglycosylated protein in an Escherichia coli prokaryotic system (REG) or as a fully glycosylated protein in mammalian cells (RMG) in a mouse challenge model using homologous RSV A2 and heterologous RSV B1 strains. We demonstrate that the unglycosylated REG generated higher protective immunity against both homologous and heterologous RSV strains, while the glycosylated RMG immunogen resulted in enhanced lung pathology and increased cytokine levels in lungs following virus challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell, viruses, and plasmids.

Vero cells (CCL-81) and A549 cells (CCL-185) were obtained from the ATCC. 293-Flp-in cells (R750-07) were obtained from Invitrogen. Vero cells, A549 cells, and 293-Flp-In cells were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM), F-12K medium, and Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (high glucose), respectively. All cell lines were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin-streptomycin (P-S), and l-glutamine and were maintained in an incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2.

RSV A2 (NR-12149) and B1 (NR-4052) strains were obtained from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH. All virus stocks were prepared by infecting subconfluent A549 cell monolayers with virus in F-12K medium with l-glutamine supplemented with 2% FBS and 1× P-S (infection medium). Virus was collected 3 to 5 days postinfection (dpi) by freeze-thawing cells twice and combining them with the supernatant. Harvested viruses were cleared of cell debris by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. Virus stocks to be used in challenge studies were pelleted by centrifugation at 7,000 rpm overnight. The pelleted virus was resuspended in F-12K medium supplemented with 50 mM HEPES and 100 mM MgSO4, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C until needed. Virus titers were determined by plaque assays in Vero cells.

Codon-optimized RSV G coding DNA for E. coli and mammalian cells was chemically synthesized. NotI and PacI sites were used for cloning the RSV A2 G ectodomain coding sequence (amino acids 67 to 298) into the T7-based pSK expression vector (23) for bacterial expression and the pSecR vector for mammalian expression (24) to express G protein in E. coli and 293Flp-In cells, respectively.

Purified RSV A2 F protein (amino acids 22 to 529) fused to a polyhistidine tag produced in insect cells, with endotoxin levels of <1 endotoxin unit (EU)/μg of protein, was obtained from Sino Biologicals.

Production of REG.

The recombinant RSV G extracellular domain (amino acids 67 to 298) was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen) and was purified as described previously (23, 25). Briefly, G protein expressed and localized in E. coli inclusion bodies (IB) was isolated by cell lysis and multiple washing steps with 1% Triton X-100. The pelleted IB containing G protein were resuspended in denaturation buffer and were centrifuged to remove debris. The protein supernatant was renatured by slowly diluting in the redox folding buffer. The renatured protein solution was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to remove the denaturing agents. The dialysate was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and was purified through a HisTrap FF chromatography column (GE Healthcare). The protein concentration was analyzed by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce), and the purity of the recombinant G protein from E. coli (REG) was determined by SDS-PAGE. The endotoxin levels of the purified protein were <1 EU/μg of protein.

Production of recombinant glycosylated G protein using 293 Flp-In cells (RMG).

293-Flp-In cells and pOG44 (plasmid expressing Flp-In recombinase) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The 293-Flp-In cell line stably expressing the RSV A2 G protein with a secretory signal peptide from the IgG κ chain was developed as described previously (24). Briefly, 293-Flp-in cells were cotransfected with the plasmids expressing Flp-in recombinase and the RSV A2 G ectodomain in DMEM (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 150 μg/ml of hygromycin for the selection of stably transfected cells. For protein expression, cells were maintained in 293 Expression Medium (Invitrogen), and the culture supernatant was collected every 3 to 4 days. The supernatant was cleared by centrifugation and was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter before purification through a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare).

Gel filtration chromatography.

Proteins at a concentration of 5 mg/ml were analyzed on a Superdex S200 XK 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and protein elution was monitored at 280 nm. Protein molecular weight (MW) marker standards (GE Healthcare) were used for column calibration and for the generation of standard curves to identify the molecular weights of the test protein samples.

PRNT.

For the plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), heat-inactivated serum was diluted 4-fold and was incubated with 20 to 60 PFU of RSV from the A2 or B1 strain for 1 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. The assay was performed in the presence of 5% guinea pig complement as described previously (26). Briefly, Vero cells were infected with a serum-virus mixture and were incubated for 1 h before the removal of the inoculum and the addition of an overlay of 0.8% methylcellulose in the infection medium. Plates were incubated for 5 to 7 days, and plaques were detected by immunostaining. Neutralization titers were calculated by adding a trend line to the neutralization curves and using the following formula to calculate 50% endpoint titers: antilog of [(50 + y-intercept)/slope].

Mouse immunization, RSV challenge, and sample collection.

All animal experiments were approved under animal protocol study number 2009-20 by the U.S. FDA institutional animal care and use committee. Four- to 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were obtained from the NCI (Frederick, MD). Mice were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) at day 0 and day 20 with 5 μg of purified RSV protein combined with Emulsigen adjuvant. Blood was collected from the tail vein on days 0, 14, and 30. On day 34, mice were anesthetized with a ketamine-xylazine cocktail and were infected intranasally (i.n.) with 106 PFU of RSV from the commonly used lab strain A2 or B1. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation either 2 or 4 days post-RSV challenge, when blood and lungs were collected. For histopathological analysis of the lungs, the right lobe of the lung was collected on days 2 and 4 post-RSV challenge by inflation with 10% neutral buffered formalin. For determination of the viral load and cytokine analysis, the left lobe of the lung was collected.

Determination of viral loads in lungs.

Lungs were weighed and homogenized in F-12K–2% FBS–1× P-S (5 ml medium/g of lung) using an Omni (Kennesaw, GA) tissue homogenizer. The supernatant was cleared by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and was used immediately for viral titration by a plaque assay in Vero cells as described above.

Measurement of cytokine levels in lungs.

All lungs were weighed and were homogenized in 5 ml of medium/g of lung, as described above, to normalize the amount of lung tissue used per sample. Homogenized lungs were further diluted in infection culture medium containing a 2× concentration of Complete EDTA Free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and were used in a Bio-Plex Pro mouse cytokine 23-plex assay according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Plates were read using a Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Lung histopathology.

Lungs were fixed in situ with 10% neutral buffered formalin and were removed from the chest cavity. Fixed lungs were embedded in a paraffin block, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) by Histoserv in a blinded fashion. Three mice per immunization and two slides per mouse were analyzed for histopathology. The slides were reviewed with an Olympus BX41 microscope. Photomicrographs were taken with the microscope and an Olympus DP71 digital camera, and images were captured using Olympus cellSens software. Lung lesions in each mouse were graded (scored) according to severity in each of the following sites: whole-lung section, bronchiolar lesions, vascular lesions, and alveolar lesions. The severity scores were as follows: 0, no lesions; 1, minimal lesions; 2, mild lesions; 3, moderate lesions; 4, severe lesions. Cell populations in five different perivascular lung inflammatory foci in three mice per vaccine group were counted following RSV challenge.

SPR.

Steady-state equilibrium binding of postvaccination mouse sera was monitored at 25°C using a ProteOn surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor (Bio-Rad). The recombinant G proteins from E. coli (REG) or 293T cells (RMG) were coupled to a GLC sensor chip via amine coupling with 500 resonance units (RU) in the test flow channels. Samples of 100 μl freshly prepared sera at a 10-fold dilution or MAbs (starting at 1 μg/ml) were injected at a flow rate of 50 μl/min (contact duration, 120 s) for association, and disassociation was performed over a 600-s interval. Responses from the protein surface were corrected for the response from a mock surface and for responses from a buffer-only injection. Prevaccination mouse sera were used as a negative control. Total antibody binding and data analysis results were calculated with Bio-Rad ProteOn Manager software (version 2.0.1).

Statistical analyses.

The statistical significances of group differences were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a Bonferroni multiple-comparison test. Correlations were calculated with a Spearman two-tailed test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant with a 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of glycosylated and nonglycosylated RSV G protein.

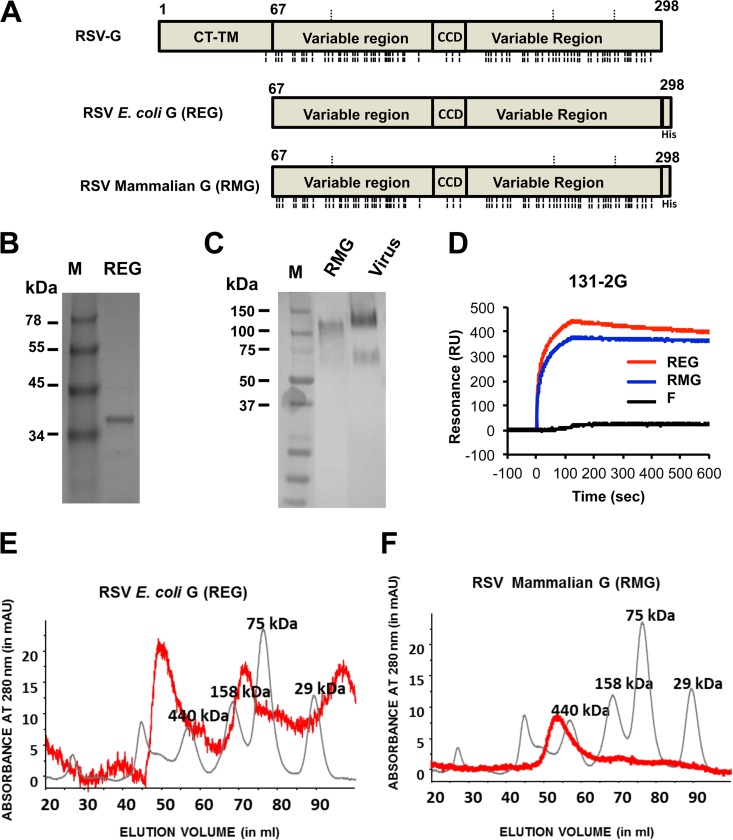

The RSV G protein from the A2 strain is a heavily glycosylated protein of 298 amino acids with N-linked and O-linked glycans in its native form (Fig. 1A) (27). To determine the impact of glycosylation on G protein immunogenicity, a nonglycosylated extracellular domain of G protein from RSV strain A2 was recombinantly produced in E. coli and was termed REG (Fig. 1A). Insoluble G protein was purified from E. coli inclusion bodies, denatured, renatured under controlled redox refolding conditions, and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The purified REG protein displayed a single band of ∼36 kDa under reducing conditions in SDS-PAGE that was recognized by Western blotting with the protective anti-G MAb 131-2G (28, 29) (Fig. 1B). To produce a native glycosylated extracellular G protein (Fig. 1A), 293-Flp-In cells were stably transfected with a plasmid expressing the ectodomain of the RSV A2 G coding sequence. The glycosylated G protein secreted in the mammalian cell culture supernatant was purified by Ni-NTA chromatography and was termed RMG. Purified glycosylated G protein (RMG) exists as a band of ∼120 kDa under reducing conditions, like the native virus-derived G protein that was recognized by anti-G MAb 131-2G by Western blotting (Fig. 1C). In addition, the two purified G ectodomains (REG and RMG) were recognized equally by MAb 131-2G in solution phase SPR (28, 29) (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Purification of recombinant G protein from E. coli and 293 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the RSV G protein. RSV G protein purified from E. coli (REG) inclusion bodies lacks the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains (CT-TM) and is not glycosylated, while the RSV G protein secreted from 293-Flp-In cells (RMG) is glycosylated. N-linked glycosylation sites, as predicted by NetNGlyc software, version 1.0, are indicated above the diagrams, and predicted O-linked glycosylation sites, as predicted by NetOGlyc software, version 4.0, are indicated below the diagrams, for the full-length RSV G and RMG proteins. REG was purified from E. coli inclusion bodies as described in Materials and Methods. RMG was purified from the clarified supernatant of 293-Flip-In cells stably expressing the RSV G protein. (B and C) Both REG (B) and RMG (C) were purified through a Ni-NTA column, and the final products were each detected as a single band by Western blotting under reducing conditions using MAb 131-2G. (D) SPR interaction profiles of binding of REG and RMG to the protective MAb 131-2G, which targets the central conserved domain of RSV G. (E and F) Superdex S200 gel filtration chromatography of RSV G protein produced in a bacterial system (REG) (E) or a mammalian system (RMG) (F). Elution profiles of purified RSV G proteins (red lines) are overlaid with calibration standards (gray lines).

To determine if these purified recombinant proteins contain higher-order quaternary forms, the purified RSV G proteins were subjected to size exclusion gel filtration chromatography (Fig. 1E and F). The in vitro-refolded, bacterially produced recombinant RSV G (REG) extracellular domain (amino acids 67 to 298) contained three MW forms representing approximately equal amounts of monomers, homotetramers, and a higher-order oligomeric form (Fig. 1E). In comparison, the glycosylated RSV G (RMG) extracellular domain (amino acids 67 to 298), purified from proteins secreted from a 293-Flp-In mammalian cell culture, contained only the homotetrameric form (Fig. 1F).

Immunization of mice with nonglycosylated REG protein generates higher binding and neutralizing antibody titers than immunization with glycosylated RMG protein.

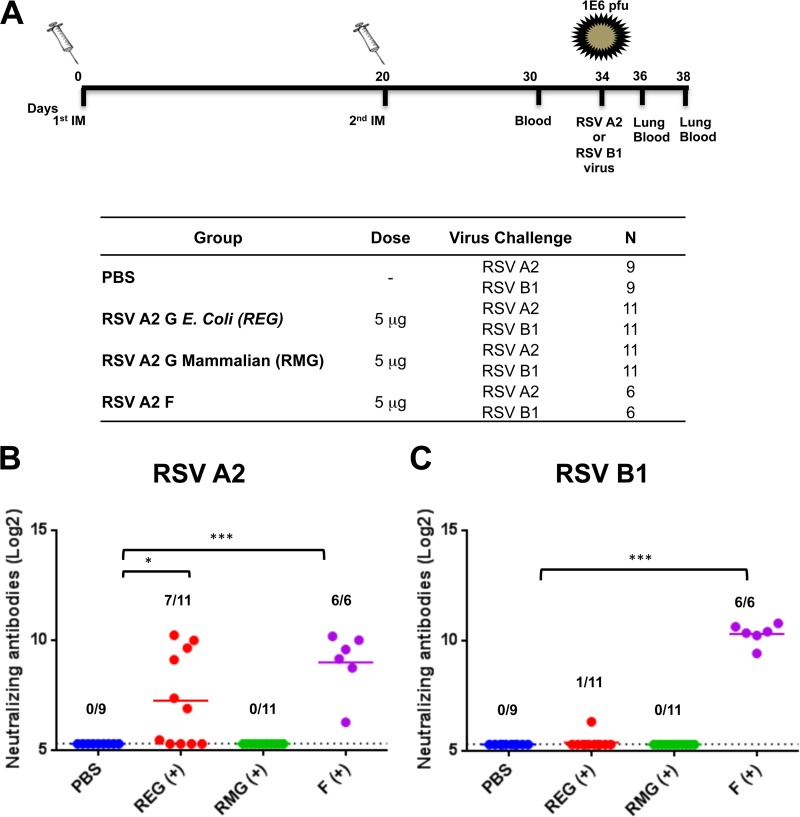

The RSV G protein is one of the two surface proteins containing neutralizing targets of RSV (20, 30). To test the antigenicity of the glycosylated (RMG) and nonglycosylated (REG) G proteins, BALB/c mice either were immunized intramuscularly twice, 20 days apart, with 5 μg of REG, RMG, or F protein from the RSV A2 strain, with Emulsigen as an adjuvant, or were mock vaccinated with PBS (Fig. 2A). Since the glycosylated and unglycosylated G ectodomains (RMG and REG, respectively) run at different MWs (Fig. 1), the doses used for vaccination were normalized by protein content to 5 μg of protein per dose (therefore, equal molarity) as determined by a BCA assay and SPR-based quantification using MAb 131-2G. The sera collected after the second immunization were tested for RSV-neutralizing activity by a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). Prevaccination (day zero) serum samples from all the animals tested negative by PRNT (data not shown). As expected, mice immunized with the F protein had high levels of neutralizing antibodies against both RSV strains, while mice immunized with PBS did not have detectable levels of anti-RSV neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 2B and C). Seven of 11 mice immunized with REG (67%) had neutralizing antibodies against homologous RSV A2 (Fig. 2B), but all had very weak or no measurable neutralizing antibodies against heterologous RSV strain B1, as measured by the PRNT (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, mice vaccinated with the glycosylated RMG did not develop RSV-neutralizing antibodies against either strain (as measured by the PRNT) after two immunizations (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

Neutralizing antibody response following RSV G (REG or RMG) or F protein immunization. (A) Schematic representation of mouse immunization and challenge schedule. BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with 5 μg of RSV strain A2 REG, RMG, or F protein with Emulsigen adjuvant, or with PBS as a control, on days 0 and 20. Ten days after the second immunization, blood was collected from the tail veins. Fourteen days after the second immunization, mice were challenged intranasally with 106 PFU of either RSV A2 or RSV B1 (6 to 11 mice per group). Mice were sacrificed on day 2 or 4 postchallenge, when lungs and blood were collected. (B and C) Serum samples collected from individual mice on day 10 after the second immunization were tested for neutralization by a PRNT against the homologous RSV A2 strain (B) or the heterologous RSV B1 strain (C). Neutralizing antibody titers represent 50% inhibition of plaque numbers. The average for each group is indicated by a horizontal line. Prevaccination (day zero) serum samples from all the animals tested negative by the PRNT (data not shown). The dotted lines indicate cutoff values based on the 1:5 dilution of sera used in PRNT. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests. ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05.

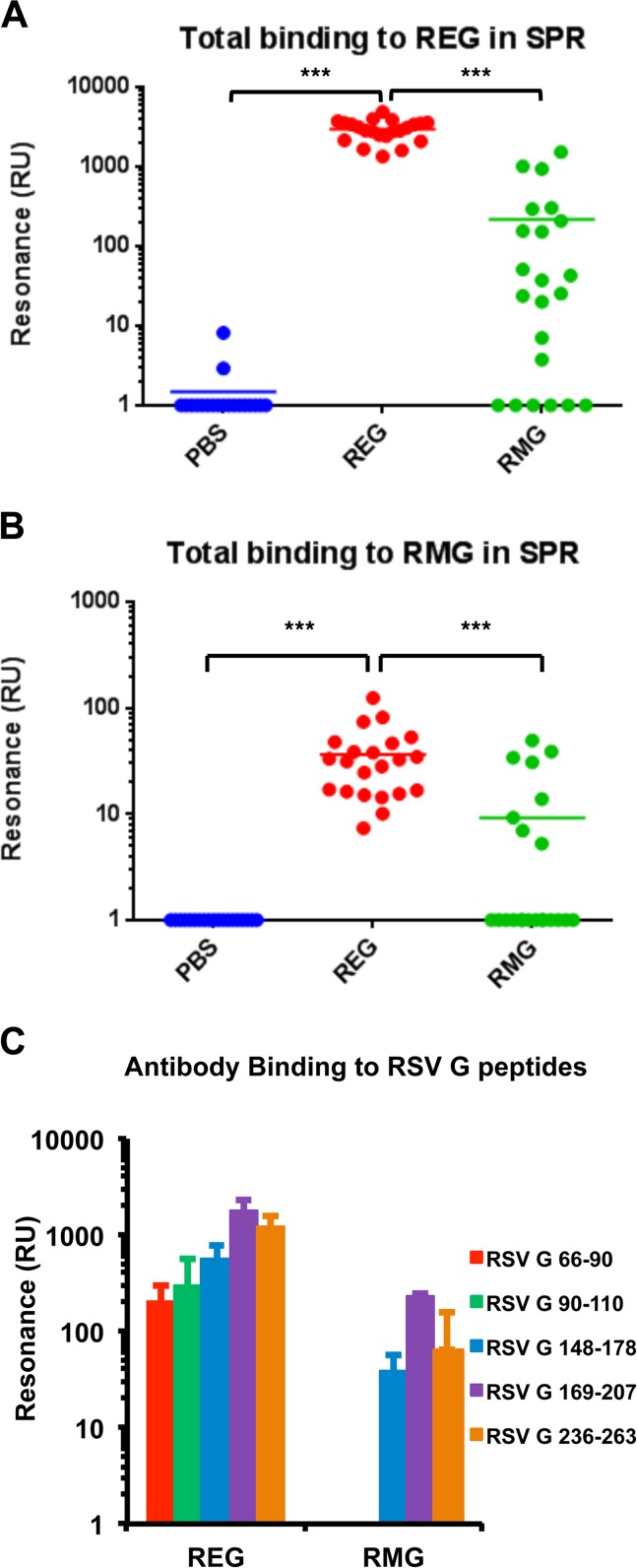

To obtain more-complete information about the antibody responses to the two recombinant G proteins in mice, an SPR-based real-time kinetics assay was used. Total anti-G binding antibody titers were measured against both the REG and RMG proteins captured on the SPR chip surface (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). As can be seen, sera from REG-immunized mice demonstrated high levels of antibodies binding to REG (Fig. 3A, red dots). Importantly, good binding to the glycosylated RMG was also observed for sera from REG-immunized mice (Fig. 3B, red dots). In comparison, sera from mice immunized with the glycosylated RMG protein gave >10-fold-lower binding to both the nonglycosylated REG and glycosylated RMG proteins by SPR (Fig. 3A and B, green dots). Therefore, the nonglycosylated REG was a better immunogen than the glycosylated RMG, generating higher levels of antibodies that recognized both the G protein sequence (unglycosylated) and the glycan-covered RSV G protein.

FIG 3.

SPR analysis of postvaccination serum antibodies to REG, RMG, and different antigenic regions within RSV G. (A and B) The same individual postvaccination mouse sera for which results are shown in Fig. 2B and C were tested for total antibody binding to the REG protein (A) or the RMG protein (B) by SPR. (C) Antigenic peptides representing amino acids 66 to 90, 90 to 110, 148 to 178, 169 to 207, or 236 to 263 of the RSV G protein were chemically synthesized and were tested for binding to serum antibodies from REG- or RMG-immunized mice in a real-time SPR kinetics experiment. Total antibody binding is represented as resonance units detected by SPR. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests. ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05.

REG vaccination generates a higher diversity of the antibody immune response than RMG vaccination.

To test which antigenic regions are recognized by antibodies generated following REG or RMG vaccination, a series of antigenic peptides derived from the N terminus, central conserved domain (CCD) (amino acid residues 164 to 186), and C terminus of the G protein were designed and were tested by SPR. Serum samples from REG-vaccinated mice showed strong binding to all G peptides, suggesting that REG induces a diverse antibody immune response that encompasses most of the RSV G protein (Fig. 3C). In contrast, sera from mice vaccinated with RMG generated antibodies that recognized peptides from the CCD and C terminus, but not the N terminus, of RSV G protein. In addition, the RMG-induced antibody titers were lower than those generated following REG vaccination for all peptides tested. These data suggested that the nonglycosylated RSV G protein can induce stronger binding antibodies against more diverse epitopes of the G protein than the glycosylated RMG immunogen.

REG immunization provides better protection than RMG immunization against both homologous and heterologous RSV challenge: G binding antibodies correlate with a reduction in lung viral loads following RSV challenge.

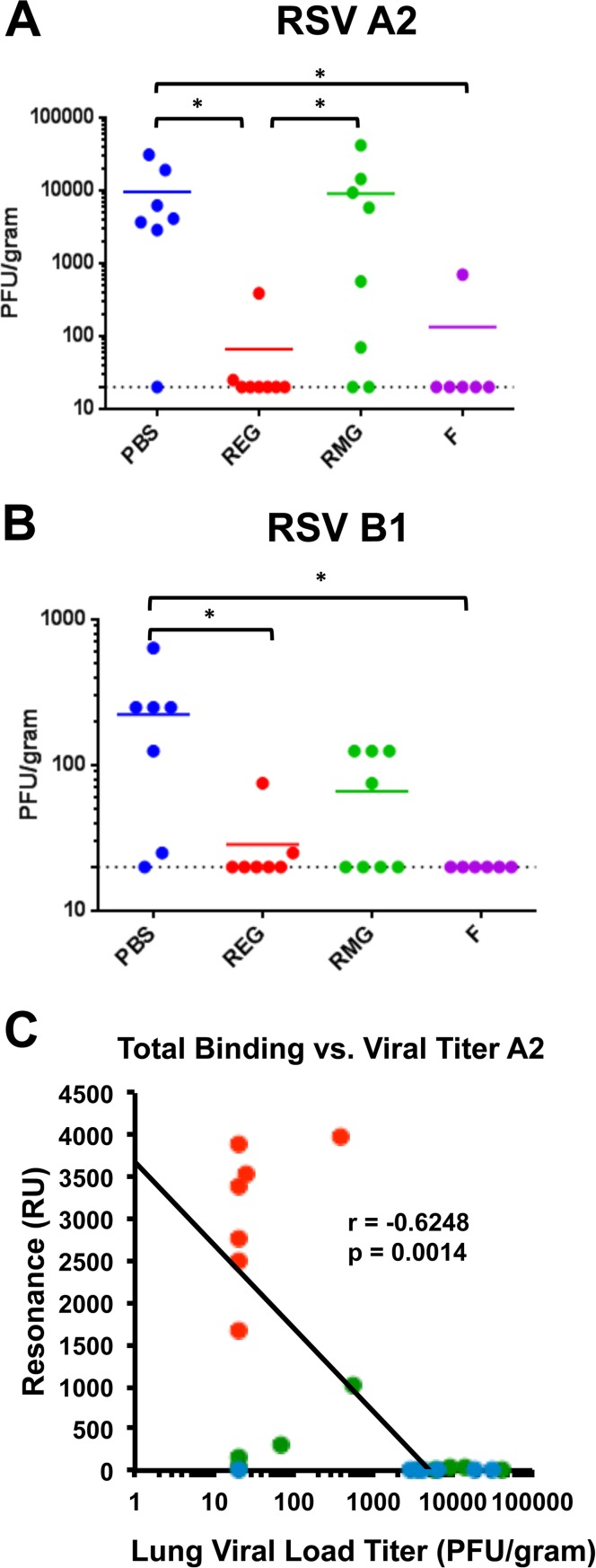

To examine whether REG or RMG immunization could protect from homologous (RSV A2) and heterologous (RSV B1) viral challenge, mice were intranasally (i.n.) infected with 1 × 106 PFU of either RSV A2 or RSV B1, 14 days after the second immunization with REG, RMG, F (positive control), or PBS (negative control). Since neither virus is lethal for mice, we measured viral loads in the lungs on day 4 postchallenge. A 2-log10 reduction in lung viral loads from those in mock (PBS)-vaccinated animals is considered good control of virus replication. The majority of F-vaccinated animals reduced viral loads to undetectable levels after challenge with either the RSV A2 or B1 strain (Fig. 4A and B, purple symbols). Among the REG-vaccinated animals, seven of eight mice were completely protected from viral replication in the lungs, and the eighth animal in each group showed a >100-fold reduction in the viral load following challenge with either the RSV A2 or B1 strain (Fig. 4A and B, red symbols). In contrast, RMG immunization conferred more-variable protection and reduction of viral loads after homologous RSV A2 (2/8 animals protected) or heterologous RSV B1 (4/8 animals protected) virus challenge (Fig. 4A and B, green symbols).

FIG 4.

Immunization with REG protects against homologous and heterologous RSV challenge. (A and B) Mice immunized twice with PBS, REG, RMG, or F protein were challenged i.n. with 1 × 106 PFU of RSV A2 (A) or RSV B1 (B) 14 days after the second immunization. Four days post-virus challenge, mouse lungs were collected and homogenized as described in Materials and Methods, and lung viral loads were determined by a plaque assay. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests, *, P < 0.05. (C) The relationship between the total anti-G antibody binding in each individual postvaccination serum sample from PBS-, REG-, and RMG-immunized mice (color coded as in panel A) measured in SPR and the lung viral load at 4 days post-RSV A2 challenge (shown in panel A) was analyzed, and Spearman's correlation was calculated. Total antibody binding to REG protein is expressed in resonance units, and lung viral loads are expressed in PFU per gram of lung. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

The lack of detectable neutralizing antibodies in mice that were completely or partially protected from challenge suggests that protection is mediated by immunological functions not captured in the traditional RSV PRNT. This is in contrast to RSV F-immunized animals, for which RSV-PRNT is a predictive assay. A relationship plot between the anti-G binding serum antibody titers of individual animals after the second immunization and lung viral loads after RSV challenge shows that anti-G binding antibody titers have a statistically significant inverse correlation with viral loads of the homologous RSV A2 strain in the lungs (Fig. 4C) (r = −0.6248; P = 0.0014). Results for the REG-vaccinated and RMG-vaccinated animals are represented by red dots and green dots, respectively (the same animals as those for which results are shown in Fig. 4A). For RSV B1, a weaker inverse correlation was found between anti-G binding antibodies and lung viral loads (r = −0.3961; P = 0.0613 [data not shown]).

Therefore, it is apparent that the REG immunogen confers better protective immunity than RMG against both homologous and heterologous RSV challenge. The correlates of protection may include immune mechanisms not measured using a classical RSV PRNT. However, total anti-G binding antibodies as measured in the SPR assay provided a strong correlate with homologous protection as measured by control of virus replication in the lungs.

Glycosylated RMG induces enhanced pathology in the lungs following virus infection, while nonglycosylated REG protein provides protection from lung pathology.

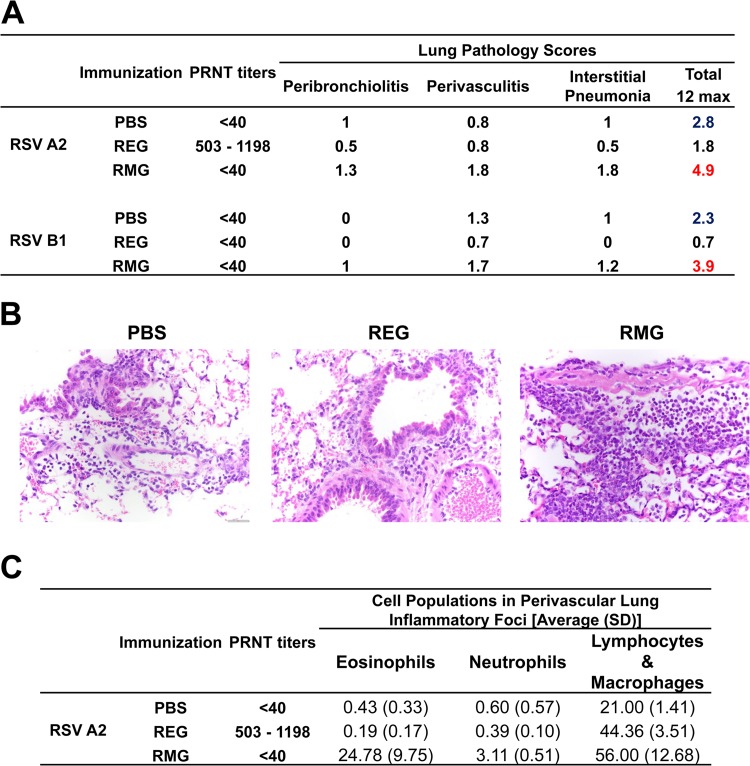

Previous studies suggested that vaccines based on RSV G protein can prime mice for enhanced lung pathology following RSV challenge, which is associated with increased cytokine production and cellular infiltration, including infiltration of eosinophils, neutrophils, and NK cells (31–35). Therefore, we investigated whether intramuscular immunization with REG or RMG leads to enhanced lung pathology following intranasal RSV challenge. The two RSV strains used in the current study, RSV A2 and B1, are known to cause mild lung pathology in mice. Lungs were collected from RSV-infected animals and were analyzed by histopathology as described in Materials and Methods. At 2 days following RSV challenge, lungs from PBS (control)-vaccinated mice showed mild pathology (Fig. 5). In contrast, lungs from RMG-immunized mice demonstrated more cellular infiltrates and higher perivasculitis and interstitial pneumonia scores than lungs from PBS-immunized mice following either homologous or heterologous RSV challenge. In contrast, REG-immunized mice showed lung pathology scores lower than those of PBS-immunized mice after infection with RSV A2. Surprisingly, scores were similarly low in REG-immunized mice following challenge with RSV B1, even though these mice lacked serum neutralizing antibodies against RSV as measured by PRNT (Fig. 5A and B). In addition, cellular infiltrates in the lungs of PBS- and REG-immunized mice were composed mostly of lymphocytes and macrophages with few eosinophils, while the lungs of RMG-immunized mice contained significantly higher numbers of eosinophils (100-fold) and neutrophils (10-fold) than the lungs of REG- or mock-immunized mice (Fig. 5C). Similar lung pathology was observed in animals on day 4 following RSV challenge (data not shown). These results suggest that the nonglycosylated REG immunogen provides good protection from RSV-mediated disease by control of lung viral loads and reduction of lung disease, while the glycosylated RMG counterpart induces enhanced pathology in the lungs following RSV infection.

FIG 5.

Histopathology analysis of lungs from REG- and RMG-immunized mice after virus challenge. REG protects, while RMG induces perivasculitis and cellular infiltrates in the lungs. Lungs collected 2 days after challenge with RSV A2 or RSV B1 were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and were scored for inflammation in bronchioles, near veins (vascular), and alveoli. (A) Lung histology scores represent the averages for 2 slides per mouse and 3 mice per group. Pathology was scored as follows: 0, no lesions; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, modest; 4, severe. The maximum pathology score (sum of peribronchiolitis, perivasculitis, and interstitial pneumonia scores) was 12. Neutralizing antibody titers represent 50% inhibition of plaque numbers as measured by PRNT against the respective RSV strains for 3 mice per group. (B) Images (magnification, ×400) of hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained lung sections. (C) Populations of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes/macrophages in five different perivascular lung inflammatory foci in three mice per vaccine group, counted 2 days following RSV A2 challenge.

Cytokine profiles in the lungs of REG- and RMG-immunized mice following virus challenge.

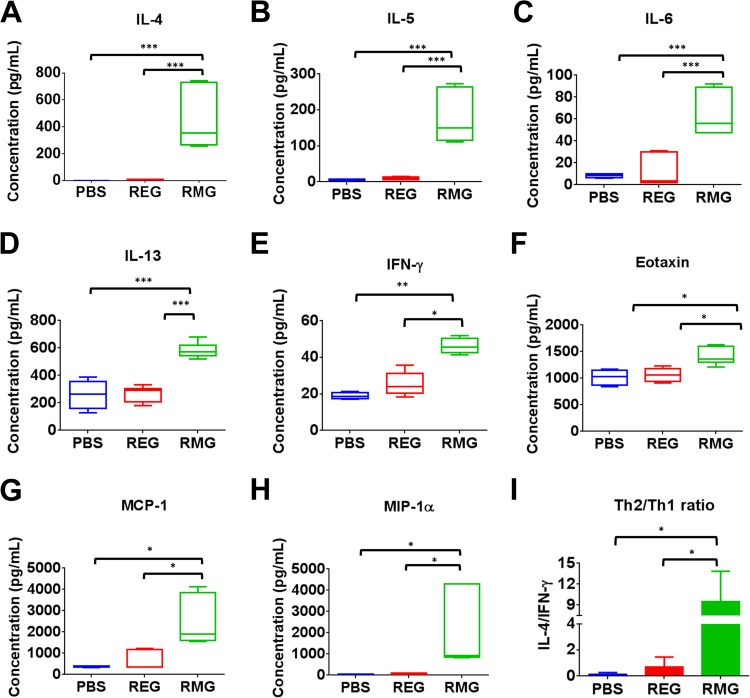

The hallmark of RSV vaccine-induced enhanced pathology in mice is an increase in cytokine expression and the development of a skewed Th2 response. Therefore, levels of Th1 or Th2 cytokines and chemokines were measured in lung homogenates of immunized mice following RSV infection (Table 1). Levels of interleukin 4 (IL-4), known to be important for the development of a Th2 response, were >100-fold higher in the lungs of RMG-immunized mice than in those of placebo (PBS)-immunized mice, while IL-4 levels in REG-immunized mice were comparable to those for the PBS control (Fig. 6A). Levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), a Th1 cytokine, were only ∼2-fold higher in RMG-immunized mice than in placebo- or REG-immunized mice (Fig. 6E). As a consequence, the ratio of Th2 to Th1 cytokines (IL-4/IFN-γ ratio) was significantly higher in the lungs of mice immunized with the RMG immunogen than in the lungs of placebo- or REG-immunized mice following RSV infection (Fig. 6I). The Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13, known to be involved in eosinophil recruitment, airway hyperresponsiveness, and mucus production (32, 36), were found at significantly higher levels in mice immunized with RMG than in placebo-immunized mice. In contrast, in the lungs of REG-immunized mice, levels of IL-5 and IL-13 were present in ranges similar to those of the placebo-immunized control lungs (Fig. 6B and D). We also identified significant production of IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine often associated with increased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and an elevation in body temperature (Fig. 6C). The chemokines eotaxin, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), previously found to be involved in RSV-induced enhanced lung pathology (37), were also observed at significantly higher levels in the lungs of RSV-challenged RMG-immunized mice than in those of REG-immunized or PBS control mice (Fig. 6F to H). The elevated levels of cytokines and chemokines in RMG-immunized mice following viral challenge seemed to be immune mediated and were independent of lung viral loads following RSV challenge, since similar or higher viral loads were observed in PBS control mice (Fig. 4).

TABLE 1.

Cytokine production in the lungs of immunized and placebo-treated mice on day 2 following RSV A2 challenge

| Cytokinea | Concn (pg/ml)b in lungs of animals immunized with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | REG | RMG | |

| Th1 cytokines | |||

| IL-1α | 39.46 ± 1.50 | 63.77 ± 15.70* | 99.71 ± 10.76*# |

| IL-1β | 460.95 ± 61.36 | 499.99 ± 108.97 | 1,341.63 ± 396.63*# |

| IL-2 | 33.07 ± 1.86 | 36.06 ± 6.22 | 57.91 ± 6.27*# |

| IL-12p40 | 105.52 ± 3.40 | 212.82 ± 109.13 | 93.97 ± 69.25 |

| IL-12p70 | 96.64 ± 14.02 | 137.21 ± 37.08 | 308.91 ± 88.60*# |

| GM-CSF | 300.06 ± 20.84 | 292.35 ± 24.43 | 336.40 ± 25.04# |

| IFN-γ | 18.96 ± 1.83 | 25.48 ± 6.37 | 46.22 ± 4.33*# |

| TNF-α | 328.87 ± 31.03 | 374.53 ± 42.91 | 644.31 ± 60.47*# |

| Th2 cytokines | |||

| IL-4 | 1 ± 0 | 3.11 ± 3.68 | 451 ± 223.96*# |

| IL-5 | 5.82 ± 1.82 | 9.83 ± 3.74 | 176.67 ± 72.08*# |

| IL-6 | 8.1 ± 1.80 | 11.92 ± 14.14 | 64.44 ± 20.06*# |

| IL-9 | 199.42 ± 34.23 | 95.41 ± 43.94 | 356.9 ± 268.40# |

| IL-13 | 260.81 ± 106.76 | 267.51 ± 56.78 | 581.69 ± 55.35*# |

| Th17 cytokines, IL-17 | 9.94 ± 0.84 | 11.36 ± 2.93 | 13.45 ± 3.17 |

| Chemokines and growth factors | |||

| Eotaxin | 1,018.32 ± 143.14 | 1,065.05 ± 132.29 | 1,413.19 ± 162.62*# |

| G-CSF | 40.35 ± 8.87 | 139.19 ± 158.40 | 136.7 ± 65.89 |

| KC | 196.76 ± 48.80 | 307.05 ± 174.47 | 564.91 ± 130.99*# |

| MCP-1 | 381.98 ± 32.60 | 626.59 ± 431.41 | 2,474.1 ± 1,153.93*# |

| MIP-1α | 50.98 ± 4.27 | 63.21 ± 23.06 | 2,025.14 ± 1,767.41*# |

| MIP-1β | 59.54 ± 7.74 | 64.41 ± 11.47 | 289.51 ± 155.53*# |

| RANTES | 272.79 ± 7.69 | 436.25 ± 194.68 | 711.81 ± 227.38* |

| Th1 + Th2-expressed cytokines | |||

| IL-3 | 11.72 ± 0.84 | 14.19 ± 2.72 | 13.65 ± 2.22 |

| IL-10 | 48.7 ± 4.12 | 61.12 ± 16.27 | 148.83 ± 16.42*# |

GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; KC, keratinocyte chemoattractant.

Values are averages for three mice ± standard deviations. Symbols indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) from levels in PBS-immunized (*) or REG-immunized (#) animals.

FIG 6.

RMG (but not REG) immunization induces high levels of Th2 cytokines and chemokines following RSV i.n. challenge. (A to H) Cytokines in lung homogenates from day 2 postchallenge were measured in a Bio-Plex Pro mouse cytokine assay. Values are concentrations, expressed in picograms per milliliter, for 3 mice per group. The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile, and the error bars represent the lowest and highest values. Values below the limit of detection of the assay were assigned a number according to the minimum detection limit of the cytokine. The mean for each group is shown. (I) Ratio of the observed concentration of Th2 cytokines to that of Th1 cytokines as measured by the IL-4/IFN-γ ratio. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests. ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05.

Taken together, the findings of this study demonstrated that RMG vaccination induces enhanced lung cellular infiltration, as measured by both histopathology and cytokine levels after RSV challenge. At the same time, the RMG vaccine does not elicit strong protective immunity. On the other hand, vaccination with the unglycosylated REG did not induce enhanced lung pathology and did confer protection against both homologous and heterologous RSV strains, even in the absence of a neutralizing antibody response as determined by PRNT.

DISCUSSION

New efforts are under way to develop subunit vaccines against RSV that will provide protective immunity without the potential for disease enhancement that was observed in infants following vaccination with the formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine in the 1960s (5, 38–40). Most recent RSV vaccine development efforts are focused on the F protein, which is relatively conserved among strains (3) and can be expressed in mammalian and insect cells (14, 18, 19, 41). The G attachment protein, expressed on the virus surface, also represents an important target of protective immunity. However, in earlier studies, glycosylated G protein expressed in mammalian cells or a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing G protein was shown in mouse models to induce pulmonary eosinophilia upon RSV infection (36, 42, 43). Therefore, we decided to evaluate side by side the immunogenicity and safety of the recombinant unglycosylated G protein ectodomain (amino acids 67 to 298) expressed in E. coli (REG) and those of a fully glycosylated G ectodomain produced in 293-Flp-In mammalian cells (RMG) in a mouse RSV challenge model. The FI-RSV model was not included in the current study, because it has been documented in previous studies, demonstrating immune response imbalance and levels of lung cytokines and cellular infiltrates that were associated with enhanced lung pathology. The targets of the nonneutralizing antibodies were not completely deciphered. Furthermore, F and G subunit vaccines studied early on have a history of disease enhancement, albeit to a lesser extent than FI-RSV (3).

Previous studies in which glycosylated G protein was shown to be protective in mice typically used three vaccinations with ≥10 μg protein per dose (44–47). In this study, we immunized mice with only two vaccinations of a lower dose of the G proteins (5 μg/dose) to determine the impacts of glycosylation on virus neutralization and the disease enhancement phenomenon after RSV infection. Two vaccinations with REG generated neutralizing antibodies against RSV A2 in 7/11 animals, while glycosylated RMG did not elicit neutralizing antibodies as measured by the PRNT. Furthermore, total binding antibodies against the recombinant proteins (both REG and RMG) were found to be >10-fold higher in REG-immunized mice sera than in RMG-vaccinated mice. REG immune sera also demonstrated broader epitope recognition, spanning the entire G ectodomain, than RMG immune sera. Homologous and heterologous protection was evaluated by measuring lung viral loads after challenge with either the RSV A2 (homologous) or the RSV B1 (heterologous) strain. Complete control of viral loads was observed in the majority of animals vaccinated with REG and challenged with either RSV strain. In contrast, the majority of RMG-vaccinated animals did not control virus replication after homologous or heterologous virus challenge. There were animals with low or no serum neutralization titers that controlled lung viral loads very well. This was most evident in animals challenged with the heterologous RSV B1 strain. It has been shown before that anti-G antibodies may neutralize virus in vivo but not in the in vitro PRNT (29). Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and/or cell-mediated immunity may also play a role in virus clearance after RSV challenge. However, previous studies showed that BALB/c mice immunized with either FI-RSV or a recombinant vaccinia virus that expresses the glycosylated RSV G attachment protein generated RSV-specific CD4+ T cells but did not prime CD8+ T cells (48, 49). In our study, a strong inverse correlation was observed between the total anti-G binding serum antibody titers (measured by SPR) and lung viral loads after RSV challenge. Therefore, it is likely that anti-G binding antibodies that are protective in vivo do not neutralize RSV in the PRNT, as was observed for anti-G MAb 131-2G (29). Therefore, this study demonstrates that for an RSV G protein-based vaccine, the correlate of protection mediated by total G-binding antibodies as measured by SPR may provide a reasonably good predictor of control of viral replication after intranasal RSV challenge. Additional studies with patient-derived RSV isolates (as they become available) are planned to confirm and expand our findings. These analytical tools could also be evaluated further in preclinical and clinical studies of other RSV vaccines containing both F and G proteins, including live-attenuated vaccines under investigation in children (11, 12).

An important safety consideration for the use of subunit and nonreplicating candidate vaccines against RSV is enhanced Th2 cytokine response and its potential to increase disease severity upon virus challenge. The RSV G glycoprotein in particular has been implicated as an RSV antigen that promotes Th2 CD4+ T lymphocytes and induces eosinophilic infiltrates in the lungs after RSV challenge (31, 32, 36, 50–53). In the current study, animals vaccinated with glycosylated RMG, but not PBS- or REG-vaccinated animals, demonstrated Th2-biased cytokine and elevated chemokine responses in the lungs that correlated with significant lung histopathology after either RSV A2 or RSV B1 challenge. The higher numbers of cellular infiltrates containing eosinophils (100-fold) and neutrophils (10-fold) in RMG-vaccinated mice following RSV challenge recapitulated the lung pathology observed previously in models of enhanced RSV disease (33, 34). The enhanced lung pathology in RMG-immunized mice following viral challenge seems to be immune mediated, since similar or higher viral loads were observed in PBS control mice, which showed lower cytokine levels and less lung pathology.

The two purified recombinant G proteins were identical in terms of their primary amino acid sequence and were administered in combination with the same adjuvant, Emulsigen. The only difference between the REG and RMG proteins was the presence of glycosylation as N- and O-linked glycans in the RMG protein. Therefore, the observed shift toward a higher Th2/Th1 ratio after RMG vaccination could not be attributed simply to binding of the CX3C motif within the CCD to CX3CR1 (the fractalkine receptor) on several cell types, as suggested previously (54–56). Instead, the enhanced Th2 cytokine and chemokine levels could possibly be induced by the high level of O-linked sugars characteristic of mammalian-cell-expressed glycosylated RMG and also of the native-virus-associated G attachment protein. A role for processing by different glycosylation-specific antigen-presenting cell subsets and routes of immunization that could influence the subsequent balance between Th2 and Th1 cytokines has been reported and should be further investigated (57–59). Carbonylation of protein is one of several factors that have been proposed to be responsible for the induction of Th2 disease in this model. However, we did not observe any difference in the carbonyl contents of the REG and RMG proteins used in our studies.

Our findings are in agreement with those of previous studies using the E. coli-produced fusion protein BBG2Na, which contained the central conserved region of the A2 G gene (amino acids 130 to 230) (G2Na) fused to the albumin-binding domain of streptococcal protein G (BB) formulated with an aluminum adjuvant (44–47). In comparison with BBG2Na, our REG encompasses the entire G ectodomain with no “foreign” sequences or fusion protein that may influence the immune response to the irrelevant target (BB rather than G2Na) during vaccinations. Most of the studies with BBG2Na used 20 μg of the vaccine in a series of three vaccinations. In contrast, in our study, only two vaccinations with 5 μg REG protein/dose elicited strong protection. Also, REG immunization induced antibodies with a more-diverse epitope repertoire than BBG2Na. In summary, our study for the first time compared side by side fully glycosylated and unglycosylated G proteins for immunogenicity and safety in a murine RSV challenge model. The combination of low virus neutralizing activity, lower G-binding antibody titers, and enhanced lung pathology observed in the RMG-vaccinated animals is in agreement with the findings of previous studies using various forms of glycosylated G proteins (31, 32, 34, 52, 60). In contrast, the lack of enhanced lung pathology after REG vaccination was an unexpected, encouraging finding that provides support for further development of this vaccine approach. It also provided data supporting the feasibility of developing a simple recombinant RSV G-based vaccine produced in an E. coli expression system that elicits protective antibodies against both homologous and heterologous RSV challenge. The bacterial production system for a G protein-based vaccine provides an economical, simple, and rapid alternative to cell-based subunit vaccines, as was previously demonstrated for influenza virus HA1 proteins from multiple virus strains (25, 61–63), and could be applied for the expression of multiple G proteins from circulating RSV strains. Such a multicomponent G immunogen could be tested alone or in combination with F-subunit vaccines for effective protection against RSV disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Judy Beeler and Haruhiko Murata for their thorough review of the manuscript. We thank Swati Verma and Nitin Verma for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou H, Thompson WW, Viboud CG, Ringholz CM, Cheng PY, Steiner C, Abedi GR, Anderson LJ, Brammer L, Shay DK. 2012. Hospitalizations associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States, 1993–2008. Clin Infect Dis 54:1427–1436. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hertz MI, Englund JA, Snover D, Bitterman PB, McGlave PB. 1989. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced acute lung injury in adult patients with bone marrow transplants: a clinical approach and review of the literature. Medicine 68:269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham BS. 2011. Biological challenges and technological opportunities for respiratory syncytial virus vaccine development. Immunol Rev 239:149–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. 2003. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, Pyles G, Chanock RM, Jensen K, Parrott RH. 1969. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 89:422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy BR, Prince GA, Walsh EE, Kim HW, Parrott RH, Hemming VG, Rodriguez WJ, Chanock RM. 1986. Dissociation between serum neutralizing and glycoprotein antibody responses of infants and children who received inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. J Clin Microbiol 24:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy BR, Walsh EE. 1988. Formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine induces antibodies to the fusion glycoprotein that are deficient in fusion-inhibiting activity. J Clin Microbiol 26:1595–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polack FP, Teng MN, Collins PL, Prince GA, Exner M, Regele H, Lirman DD, Rabold R, Hoffman SJ, Karp CL, Kleeberger SR, Wills-Karp M, Karron RA. 2002. A role for immune complexes in enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Exp Med 196:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham BS, Henderson GS, Tang YW, Lu X, Neuzil KM, Colley DG. 1993. Priming immunization determines T helper cytokine mRNA expression patterns in lungs of mice challenged with respiratory syncytial virus. J Immunol 151:2032–2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connors M, Kulkarni AB, Firestone CY, Holmes KL, Morse HC III, Sotnikov AV, Murphy BR. 1992. Pulmonary histopathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge of formalin-inactivated RSV-immunized BALB/c mice is abrogated by depletion of CD4+ T cells. J Virol 66:7444–7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright PF, Karron RA, Belshe RB, Thompson J, Crowe JE Jr, Boyce TG, Halburnt LL, Reed GW, Whitehead SS, Anderson EL, Wittek AE, Casey R, Eichelberger M, Thumar B, Randolph VB, Udem SA, Chanock RM, Murphy BR. 2000. Evaluation of a live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive, respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate in infancy. J Infect Dis 182:1331–1342. doi: 10.1086/315859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotard AL, Shaikh FY, Lee S, Yan D, Teng MN, Plemper RK, Crowe JE Jr, Moore ML. 2012. A stabilized respiratory syncytial virus reverse genetics system amenable to recombination-mediated mutagenesis. Virology 434:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karron RA, Wright PF, Belshe RB, Thumar B, Casey R, Newman F, Polack FP, Randolph VB, Deatly A, Hackell J, Gruber W, Murphy BR, Collins PL. 2005. Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis 191:1093–1104. doi: 10.1086/427813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghunandan R, Lu H, Zhou B, Xabier MG, Massare MJ, Flyer DC, Fries LF, Smith GE, Glenn GM. 2014. An insect cell derived respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F nanoparticle vaccine induces antigenic site II antibodies and protects against RSV challenge in cotton rats by active and passive immunization. Vaccine 32:6485–6492. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falsey AR, Walsh EE. 1996. Safety and immunogenicity of a respiratory syncytial virus subunit vaccine (PFP-2) in ambulatory adults over age 60. Vaccine 14:1214–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langley JM, Sales V, McGeer A, Guasparini R, Predy G, Meekison W, Li M, Capellan J, Wang E. 2009. A dose-ranging study of a subunit respiratory syncytial virus subtype A vaccine with and without aluminum phosphate adjuvantation in adults > or =65 years of age. Vaccine 27:5913–5919. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ofek G, Guenaga FJ, Schief WR, Skinner J, Baker D, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. 2010. Elicitation of structure-specific antibodies by epitope scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:17880–17887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004728107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson KA, Balabanis K, Xie Y, Aggarwal Y, Palomo C, Mas V, Metrick C, Yang H, Shaw CA, Melero JA, Dormitzer PR, Carfi A. 2014. A monomeric uncleaved respiratory syncytial virus F antigen retains prefusion-specific neutralizing epitopes. J Virol 88:11802–11810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLellan JS, Chen M, Leung S, Graepel KW, Du X, Yang Y, Zhou T, Baxa U, Yasuda E, Beaumont T, Kumar A, Modjarrad K, Zheng Z, Zhao M, Xia N, Kwong PD, Graham BS. 2013. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science 340:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1234914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorquera PA, Choi Y, Oakley KE, Powell TJ, Boyd JG, Palath N, Haynes LM, Anderson LJ, Tripp RA. 2013. Nanoparticle vaccines encompassing the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) G protein CX3C chemokine motif induce robust immunity protecting from challenge and disease. PLoS One 8:e74905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Power UF, Nguyen TN, Rietveld E, de Swart RL, Groen J, Osterhaus AD, de Groot R, Corvaia N, Beck A, Bouveret-Le-Cam N, Bonnefoy JY. 2001. Safety and immunogenicity of a novel recombinant subunit respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (BBG2Na) in healthy young adults. J Infect Dis 184:1456–1460. doi: 10.1086/324426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Waal L, Power UF, Yuksel S, van Amerongen G, Nguyen TN, Niesters HG, de Swart RL, Osterhaus AD. 2004. Evaluation of BBG2Na in infant macaques: specific immune responses after vaccination and RSV challenge. Vaccine 22:915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khurana S, Larkin C, Verma S, Joshi MB, Fontana J, Steven AC, King LR, Manischewitz J, McCormick W, Gupta RK, Golding H. 2011. Recombinant HA1 produced in E. coli forms functional oligomers and generates strain-specific SRID potency antibodies for pandemic influenza vaccines. Vaccine 29:5657–5665. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu H, Khurana S, Verma N, Manischewitz J, King L, Beigel JH, Golding H. 2011. A rapid Flp-In system for expression of secreted H5N1 influenza hemagglutinin vaccine immunogen in mammalian cells. PLoS One 6:e17297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khurana S, Verma S, Verma N, Crevar CJ, Carter DM, Manischewitz J, King LR, Ross TM, Golding H. 2011. Bacterial HA1 vaccine against pandemic H5N1 influenza virus: evidence of oligomerization, hemagglutination, and cross-protective immunity in ferrets. J Virol 85:1246–1256. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02107-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuentes S, Crim RL, Beeler J, Teng MN, Golding H, Khurana S. 2013. Development of a simple, rapid, sensitive, high-throughput luciferase reporter based microneutralization test for measurement of virus neutralizing antibodies following respiratory syncytial virus vaccination and infection. Vaccine 31:3987–3994. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satake M, Coligan JE, Elango N, Norrby E, Venkatesan S. 1985. Respiratory syncytial virus envelope glycoprotein (G) has a novel structure. Nucleic Acids Res 13:7795–7812. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.21.7795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson LJ, Hierholzer JC, Stone YO, Tsou C, Fernie BF. 1986. Identification of epitopes on respiratory syncytial virus proteins by competitive binding immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol 23:475–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson LJ, Bingham P, Hierholzer JC. 1988. Neutralization of respiratory syncytial virus by individual and mixtures of F and G protein monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 62:4232–4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y, Mason CS, Jones LP, Crabtree J, Jorquera PA, Tripp RA. 2012. Antibodies to the central conserved region of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) G protein block RSV G protein CX3C-CX3CR1 binding and cross-neutralize RSV A and B strains. Viral Immunol 25:193–203. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson TR, Johnson JE, Roberts SR, Wertz GW, Parker RA, Graham BS. 1998. Priming with secreted glycoprotein G of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) augments interleukin-5 production and tissue eosinophilia after RSV challenge. J Virol 72:2871–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson TR, Graham BS. 1999. Secreted respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein induces interleukin-5 (IL-5), IL-13, and eosinophilia by an IL-4-independent mechanism. J Virol 73:8485–8495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tripp RA, Moore D, Jones L, Sullender W, Winter J, Anderson LJ. 1999. Respiratory syncytial virus G and/or SH protein alters Th1 cytokines, natural killer cells, and neutrophils responding to pulmonary infection in BALB/c mice. J Virol 73:7099–7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripp RA, Moore D, Winter J, Anderson LJ. 2000. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and G and/or SH protein expression contribute to substance P, which mediates inflammation and enhanced pulmonary disease in BALB/c mice. J Virol 74:1614–1622. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.4.1614-1622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripp RA, Moore D, Anderson LJ. 2000. TH1- and TH2-type cytokine expression by activated T lymphocytes from the lung and spleen during the inflammatory response to respiratory syncytial virus. Cytokine 12:801–807. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castilow EM, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM. 2008. IL-13 is required for eosinophil entry into the lung during respiratory syncytial virus vaccine-enhanced disease. J Immunol 180:2376–2384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jafri HS, Chavez-Bueno S, Mejias A, Gomez AM, Rios AM, Nassi SS, Yusuf M, Kapur P, Hardy RD, Hatfield J, Rogers BB, Krisher K, Ramilo O. 2004. Respiratory syncytial virus induces pneumonia, cytokine response, airway obstruction, and chronic inflammatory infiltrates associated with long-term airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Infect Dis 189:1856–1865. doi: 10.1086/386372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapikian AZ, Mitchell RH, Chanock RM, Shvedoff RA, Stewart CE. 1969. An epidemiologic study of altered clinical reactivity to respiratory syncytial (RS) virus infection in children previously vaccinated with an inactivated RS virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 89:405–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fulginiti VA, Eller JJ, Sieber OF, Joyner JW, Minamitani M, Meiklejohn G. 1969. Respiratory virus immunization. I. A field trial of two inactivated respiratory virus vaccines; an aqueous trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine and an alum-precipitated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol 89:435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chin J, Magoffin RL, Shearer LA, Schieble JH, Lennette EH. 1969. Field evaluation of a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and a trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine in a pediatric population. Am J Epidemiol 89:449–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JS, Kwon YM, Hwang HS, Lee YN, Ko EJ, Yoo SE, Kim MC, Kim KH, Cho MK, Lee YT, Lee YR, Quan FS, Kang SM. 2014. Baculovirus-expressed virus-like particle vaccine in combination with DNA encoding the fusion protein confers protection against respiratory syncytial virus. Vaccine 32:5866–5874. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Openshaw PJ, Clarke SL, Record FM. 1992. Pulmonary eosinophilic response to respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice sensitized to the major surface glycoprotein G. Int Immunol 4:493–500. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Everard ML, Swarbrick A, Wrightham M, McIntyre J, Dunkley C, James PD, Sewell HF, Milner AD. 1994. Analysis of cells obtained by bronchial lavage of infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Arch Dis Child 71:428–432. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.5.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Power UF, Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Huss T, Robert A, Trudel M, Stahl S, Uhlen M, Nguyen TN, Binz H. 1997. Induction of protective immunity in rodents by vaccination with a prokaryotically expressed recombinant fusion protein containing a respiratory syncytial virus G protein fragment. Virology 230:155–166. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plotnicky-Gilquin H, Huss T, Aubry JP, Haeuw JF, Beck A, Bonnefoy JY, Nguyen TN, Power UF. 1999. Absence of lung immunopathology following respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge in mice immunized with a recombinant RSV G protein fragment. Virology 258:128–140. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corvaïa N, Tournier P, Nguyen TN, Haeuw JF, Power UF, Binz H, Andreoni C. 1997. Challenge of BALB/c mice with respiratory syncytial virus does not enhance the Th2 pathway induced after immunization with a recombinant G fusion protein, BBG2NA, in aluminum hydroxide. J Infect Dis 176:560–569. doi: 10.1086/514075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Power UF, Plotnicky H, Blaecke A, Nguyen TN. 2003. The immunogenicity, protective efficacy and safety of BBG2Na, a subunit respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine candidate, against RSV-B. Vaccine 22:168–176. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00570-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olson MR, Varga SM. 2007. CD8 T cells inhibit respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine-enhanced disease. J Immunol 179:5415–5424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olson MR, Hartwig SM, Varga SM. 2008. The number of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-specific memory CD8 T cells in the lung is critical for their ability to inhibit RSV vaccine-enhanced pulmonary eosinophilia. J Immunol 181:7958–7968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alwan WH, Openshaw PJ. 1993. Distinct patterns of T- and B-cell immunity to respiratory syncytial virus induced by individual viral proteins. Vaccine 11:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alwan WH, Record FM, Openshaw PJ. 1993. Phenotypic and functional characterization of T cell lines specific for individual respiratory syncytial virus proteins. J Immunol 150:5211–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hancock GE, Speelman DJ, Heers K, Bortell E, Smith J, Cosco C. 1996. Generation of atypical pulmonary inflammatory responses in BALB/c mice after immunization with the native attachment (G) glycoprotein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol 70:7783–7791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srikiatkhachorn A, Braciale TJ. 1997. Virus-specific memory and effector T lymphocytes exhibit different cytokine responses to antigens during experimental murine respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol 71:678–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haynes LM, Jones LP, Barskey A, Anderson LJ, Tripp RA. 2003. Enhanced disease and pulmonary eosinophilia associated with formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccination are linked to G glycoprotein CX3C-CX3CR1 interaction and expression of substance P. J Virol 77:9831–9844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9831-9844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sparer TE, Matthews S, Hussell T, Rae AJ, Garcia-Barreno B, Melero JA, Openshaw PJ. 1998. Eliminating a region of respiratory syncytial virus attachment protein allows induction of protective immunity without vaccine-enhanced lung eosinophilia. J Exp Med 187:1921–1926. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chirkova T, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gaston KA, Malik FM, Trau SP, Oomens AG, Anderson LJ. 2013. Respiratory syncytial virus G protein CX3C motif impairs human airway epithelial and immune cell responses. J Virol 87:13466–13479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01741-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rissoan MC, Soumelis V, Kadowaki N, Grouard G, Briere F, de Waal Malefyt R, Liu YJ. 1999. Reciprocal control of T helper cell and dendritic cell differentiation. Science 283:1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson TR, McLellan JS, Graham BS. 2012. Respiratory syncytial virus glycoprotein G interacts with DC-SIGN and L-SIGN to activate ERK1 and ERK2. J Virol 86:1339–1347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06096-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bembridge GP, Garcia-Beato R, Lopez JA, Melero JA, Taylor G. 1998. Subcellular site of expression and route of vaccination influence pulmonary eosinophilia following respiratory syncytial virus challenge in BALB/c mice sensitized to the attachment G protein. J Immunol 161:2473–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tebbey PW, Hagen M, Hancock GE. 1998. Atypical pulmonary eosinophilia is mediated by a specific amino acid sequence of the attachment (G) protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med 188:1967–1972. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khurana S, Verma S, Verma N, Crevar CJ, Carter DM, Manischewitz J, King LR, Ross TM, Golding H. 2010. Properly folded bacterially expressed H1N1 hemagglutinin globular head and ectodomain vaccines protect ferrets against H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. PLoS One 5:e11548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62.Verma S, Dimitrova M, Munjal A, Fontana J, Crevar CJ, Carter DM, Ross TM, Khurana S, Golding H. 2012. Oligomeric recombinant H5 HA1 vaccine produced in bacteria protects ferrets from homologous and heterologous wild-type H5N1 influenza challenge and controls viral loads better than subunit H5N1 vaccine by eliciting high-affinity antibodies. J Virol 86:12283–12293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01596-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khurana S, Coyle EM, Verma S, King LR, Manischewitz J, Crevar CJ, Carter DM, Ross TM, Golding H. 2014. H5 N-terminal beta sheet promotes oligomerization of H7-HA1 that induces better antibody affinity maturation and enhanced protection against H7N7 and H7N9 viruses compared to inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine 32:6421–6432. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]