Abstract

Using neuroeconomic approaches, our findings demonstrate that the underlying duality of the β-δ discounting networks that jointly influence valuation is impaired to a pathogenic state in abstinent heroin dependents. The imbalanced functional link between the β-δ networks for valuation may orchestrate the irrational choice in drug addiction.

Keywords: neuroeconomics, valuation network, resting-state functional connectivity MRI, temporal bounding, heroin addiction

The distinguishing feature of drug addiction is loss of volition to control drug-taking behaviors. At the neural system levels, however, the precise mechanisms underlying the failure are far from clear. Recent advances in neuroeconomic studies with task-driven functional MRI (fMRI) methods have identified two distinct brain networks that jointly influence decision-making processes.1,2 One, the ventral valuation network, or the β-network in neuroeconomic terms, mediates for immediate rewards, and involves the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), ventral striatum and ventral medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). The other is the executive control network, or δ-network, which is related to delayed rewards, and involves the lateral prefrontal and parietal cortices.2 It is challenging to understand how changes in the valuation networks could result in irrational addictive behaviors.3 Using neuroeconomic approaches, we hypothesize that the underlying duality of the β-δ discounting networks that jointly influence valuation is impaired to a pathogenic state in abstinent heroin dependents. To test this hypothesis, we first employed the intrinsic spontaneous blood oxygenation level-dependent (iBOLD) signal measured by the resting-state functional MRI (R-fMRI) to replace the traditional BOLD signal activated by task-driven paradigms.4 Second, we applied the temporal binding model5 with seed-based iBOLD signals to establish the link between the β- and δ-networks and measure their imbalanced interaction with a large-scale network analysis method.2

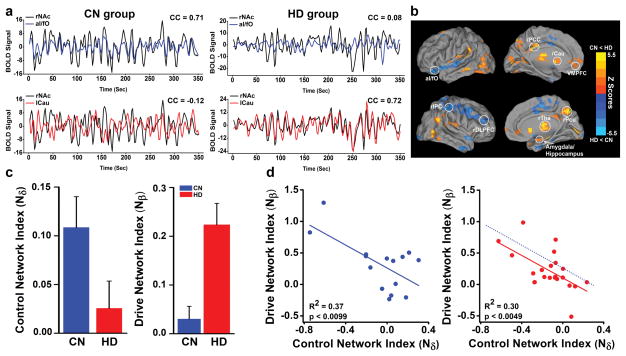

Thirty-seven male, right-handed volunteers were recruited (22 heroin-dependent (HD) subjects and 15 nondrug users as control [CN] subjects). All underwent R-fMRI data acquisition. The characterization of the study subjects, inclusion and exclusion criteria, imaging data preprocessing and seed-based postprocessing procedures have been previously published6 and are briefly presented in supplemental information section (Table S1). We selected the nucleus accumbens (NAc) region as a connective node or a “seed” region to link between the β- and δ-networks because the NAc plays an important role in drug addiction.7 Figure 1a (top row) illustrates the manner in which the iBOLD signals between regions of the anterior insula/frontal operculum (aI/fO) and NAc were desynchronized in HD subjects than in CN subjects.4 Since the synchronization of brain signals between neural systems is crucial in facilitating neural communications, as suggested by the temporal binding model, the decreased synchrony between (aI/fO) and NAc pair indicate that heroin use may destabilize the neural control systems.8

Figure 1.

a) The representative illustration of synchronization patterns of iBOLD signals from the rNAc-left aI/fO pair (top row) and from the rNAc-left caudate (lCau) pair (bottom row) in CN and HD groups, respectively; b) the regions of increased synchronization in the β-network and decreased synchronization in the δ-network linked to NAc in HD subjects, compared to CN subjects; c) Composite numerical indices of the δ- and β-networks in CN and HD groups; d) The inverse relationship between Nβ and Nδ indices in CN (left) and HD group (right), respectively. The dashed blue line (right) is a duplicate line of the CN group (left), showing a left shift of the curve in the HD group.

The improper function between aI/fO and NAc regions in HD subjects is only one aspect of loss of volition. We examined the functional synchrony between the regional iBOLD signals in the left caudate (lCau) and NAc. As illustrated in Fig. 1a (bottom row), the synchronization of lCau-NAc pair in the HD group is significantly higher than in CN group. The strong link between the ventral (i.e., NAc) and the dorsal region of striatum (i.e., lCau) through so-called “spiraling” connections9 in the HD group indicated the strong trait of motivational drive, as demonstrated previously in animal study.10

It is plausible that the failure of the top-down executive control and enduring motivational drive involved very complex systems beyond the brain regions that were tested above. With the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), Fig. 1b shows the group differences in voxelwise functional connectivity patterns. Specifically, in the β-network, the functional connectivity strengths linked between NAc and the bilateral caudate, amygdala, thalamus and vmPFC are significantly increased in the HD group in comparison to the CN group. In contrast, in the δ-network, the connectivity strengths linked between the NAc and the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, the anterior insula/frontal operculum (aI/fO) and other frontal-parietal regions are significantly decreased in the HD group in comparison to the CN group. (Please see Supplemental Materials Table S2)

Next, we converted the voxelwise functional connectivity patterns in Fig. 1b into a composite numerical presentation to examine if the imbalanced interactions between β- and δ-networks are present. By averaging the voxelwise functional connectivity (CC values) over the regions of β network in Fig. 1b, a composite functional connectivity index can be obtained, defined as the Nβ index. Similarly, an index for the δ-network can be obtained as the Nδ index. Figure 1c showed that the Nδ index is lower, whereas the Nβ index is higher in the HD group than in the CN group. These results suggest that through the links to NAc the β- and δ-networks were engaged in the imbalanced interaction in the HD group.

We further examined if the network activity between β-network and δ-networks is inversely proportional for individual subjects. Figure 1d shows that the indices of Nβ and Nδ have a significant inverse relationship (F(1,13) = 9.10, p<0.0099 for the CN group; F(1,20) = 10.02, p<0.0049 for HD group), indicating the stronger the β-network activity, the weaker the δ-network activity, suggesting “gating” mechanisms in that a strong motivational state could open the gate of the executive control circuits.11 The left shift of the curve for HD individuals may indicate that these individuals have a weaker executive control capacity than the CN subjects under the same motivational drive.

Our results implicated that the strong β-network activity of reward overdrives the δ-networks activity of inhibitory control that altered the valuation-based decision-making process toward the immediate reward, resulting in the impulsive drug-taking behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Carrie M. O’Connor, MA, for editorial assistance, Mr. B. Douglas Ward, MS, for discussions on the statistical analysis. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 81271470, AWS12J003 (ZY) and National Institutes of Health grant, RO1 DA10214 (SJL).

Footnotes

Competing financial interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Montague PR, Berns GS. Neural economics and the biological substrates of valuation. Neuron. 2002;36(2):265–284. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClure SM, Ericson KM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD. Time discounting for primary rewards. J Neurosci. 2007;27(21):5796–5804. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4246-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monterosso J, Piray P, Luo S. Neuroeconomics and the Study of Addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(9):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel AK, Fries P, Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top-down processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(10):704–716. doi: 10.1038/35094565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie C, Li SJ, Shao Y, Fu L, Goveas J, Ye E, et al. Identification of hyperactive intrinsic amygdala network connectivity associated with impulsivity in abstinent heroin addicts. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216(2):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dosenbach NUF, Fair DA, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12(3):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haber SN, Fudge JL, McFarland NR. Striatonigrostriatal pathways in primates form an ascending spiral from the shell to the dorsolateral striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20(6):2369–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02369.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320(5881):1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.