Abstract

Mutations in imprinted genes or their imprint control regions (ICRs) produce changes in imprinted gene expression and distinct abnormalities in placental structure, indicating the importance of genomic imprinting to placental development. We have recently shown that a very broad spectrum of placental abnormalities associated with altered imprinted gene expression occurs in the absence of the oocyte–derived DNMT1o cytosine methyltransferase, which normally maintains parent-specific imprinted methylation during preimplantation. The absence of DNMT1o partially reduces inherited imprinted methylation while retaining the genetic integrity of imprinted genes and their ICRs. Using this novel system, we undertook a broad and inclusive approach to identifying key ICRs involved in placental development by correlating loss of imprinted DNA methylation with abnormal placental phenotypes in a mid-gestation window (E12.5-E15.5). To these ends we measured DNA CpG methylation at 15 imprinted gametic differentially methylated domains (gDMDs) that overlap known ICRs using EpiTYPER-mass array technology, and linked these epigenetic measurements to histomorphological defects. Methylation of some imprinted gDMDs, most notably Dlk1, was nearly normal in mid-gestation DNMT1o-deficient placentas, consistent with the notion that cells having lost methylation on these DMDs do not contribute significantly to placental development. Most imprinted gDMDs however showed a wide range of methylation loss among DNMT1o-deficient placentas. Two striking associations were observed. First, loss of DNA methylation at the Peg10 imprinted gDMD associated with decreased embryonic viability and decreased labyrinthine volume. Second, loss of methylation at the Kcnq1 imprinted gDMD was strongly associated with trophoblast giant cell (TGC) expansion. We conclude that the Peg10 and Kcnq1 ICRs are key regulators of mid-gestation placental function.

Introduction

The process of genomic imprinting establishes and maintains parental alleles in opposing epigenetic states resulting in expression of imprinted genes from just one parental allele. This monoallelic imprinted gene expression is determined by inherited parent-specific DNA methylation patterns at autosomal gametic differentially methylated domains (gDMDs) that are perpetuated in the embryo such that one parental allele is methylated and the other is unmethylated. The epigenetic information inherited on gDMDs is thought to be critical for the control of imprinted gene expression patterns because they overlap or are adjacent to imprinting control regions (ICRs), the sequences defined genetically in humans and mice as required for allele-specific expression of many linked imprinted genes [1]. There are 24 confirmed imprinted gDMDs in mouse (21 maternal and 3 paternal), most of which are conserved in humans [2]. Propagation of imprinted gDMD methylation during preimplantation development is catalyzed by a combination of somatic and oocyte-specific isoforms of the maintenance DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1s and DNMT1o) [3]. Partial disruption of genomic imprint inheritance during preimplantation, through maternal deletion of DNMT1o, permanently ablates affected gDMD methylation from embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages and directly results in biallelic expression or repression of nearby clusters of imprinted genes [4,5].

The importance of genomic imprinting to fetal growth and development is evident when monoallelic expression is altered. The overgrowth syndrome Beckwith Wiedemann (BWS: OMIM 130650) and the growth restriction syndrome Silver-Russell (SRS: OMIM 180860) are caused by aberrant imprinted gene dosage at chromosome 11p15.5 [6–10]. Causes include uniparental disomies (UPD), reciprocal translocations, imprinted gene mutations or epigenetic mutations resulting in two alleles with the same imprinted status. Many of the imprinted genes of the Kcnq1 and H19 clusters that are associated with BWS and SRS are expressed and function in the placenta [11,12], and it is possible that BWS and SRS phenotypes are influenced by loss of imprinting within the placenta [13]. For example, the fetal lethality associated with deletion of the Ascl2 gene in the mouse Kcnq1 cluster is due to minimal placenta labyrinth development and accompanying accumulation of trophoblast giant cells (TGCs) at E10.5 [14]. Deletion of either the Phlda2 or Cdkn1c genes, which also reside in the Kcnq1 cluster, results in placental overgrowth [15,16] and transgenic over-expression of either Phlda2 or Cdkn1c results in poor growth of the placenta [17–19]. Placenta growth and development is also dependent on Igf2, a component of the H19 imprinting cluster; deletion of Igf2 results in placental and fetal growth restriction and overexpression of Igf2 produces a large placenta and accompanying fetus [20–22]. In addition, deletion of other imprinted genes not within the Kcnq1 or H19 clusters exhibit abnormal placental phenotypes. For example, deletion of Grb10, Igf2r, or Mest alters placental growth and deletion of either Peg10 or Rtl1 disrupts labyrinth development [23–27].

The Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect mouse model of loss of genomic imprinting is a unique system to probe the essential role of imprinted gDMD methylation in placental development. Embryos derived from homozygous Dnmt1 Δ1o/Δ1o dams lacking the oocyte isoform of DNA-methyltransferase-1 (DNMT1o) are comprised of an epigenetic mosaic of cells with partial and highly variable loss of imprinted DNA methylation [3–5]. Unlike mouse models of Dnmt1 inactivating mutations, which exhibit severe reduction in global DNA methylation and arrest development at embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) [28,29], progeny of Dnmt1 Δ1o/Δ1o dams frequently survive through mid-gestation, albeit with profound embryonic and placental defects [30,31]. Early Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect placental abnormalities are worse in female conceptuses due to defective X-chromosome inactivation [32].

In principle, the wide spectrum of phenotypes and highly variable patterns of gDMD methylation in progeny of Dnmt1 Δ1o/Δ1o dams are associated. In clinical studies the application of quantitative imprinted gDMD methylation analysis has revealed meaningful associations between abnormal gDMD methylation and specific BWS and SRS phenotypes [33,34]. The Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model provides a means to define relationships between variable loss of DNA methylation at multiple gDMDs and overt placental phenotypes. This notion is supported by our previous finding that the ratio of fetal to placental weight at E17.5 is associated with changes in expression of Ascl2 and Mest, presumably brought about by changes in gDMD methylation [31].

Previously we demonstrated wide-ranging placental abnormalities in DNMT1o-deficient placentas at early (E9.5) and late (E17.5) gestational times [31]. At E9.5 mutant placentas were prone to TGC accumulation and disorganized labyrinth development. Late in gestation DNMT1o-deficient placentas had greater spongiotrophoblast content and reduced labyrinth vascular surface area. In our most recent work [35] we found E17.5 DNMT1o-deficient placentas to accumulate excess lipids and have dysfunctional mitochondrial metabolism. We revealed a strong association between loss of methylation at the Mest gDMD and triacylglycerol levels by regression analysis. In our current study we sought to discern which genomic imprints when lost have the greatest adverse effect on placenta development and function at mid-gestational time points between E12.5 and E17.5.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

Mouse Colony and Placenta Dissections

The Dnmt 1 Δ1o mouse colony was maintained under IUPAC guidelines on a 129/Sv strain background (Taconic). Pregnant Dnmt1 Δ1o/ Δ1o dams were sacrificed at 12.5, 15.5 or 17.5 days post copulation. Conceptuses were dissected to isolate the fetus, yolk sac, and placenta under a MZ12.5 dissection microscope (Leica). Placental and fetal wet weights were measured. Maternal decidua caps were removed from placental portions designated for nucleic acid and lipid extractions but not from portions for histological analysis. Each placenta was cut into halves for preservation in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for histology or in RNA Later (Life Technologies) for nucleic acid extraction.

Histology and in situ hybridization

Following fixation in 4% PFA, placental halves were suspended through a sucrose gradient up to 20% weight per volume, and then embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura). Placental cryosections of 5μm and 10μm thickness were cut with a CM1850 cryostat (Leica) for histological analysis. Regressive hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on a series of 5 micron meridian placental sections. A series of 10μm sections were stained by in situ hybridization (ISH) with Digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche) labeled antisense RNA probes. ISH probes of the placental marker genes Tpbpa, LepR, Pchdh12, Mest, Prl2c2, Prl3b1 and Prl3d1 were in-vitro transcribed (Promega) from cDNA cloned into pBluescript, and used to identify the spongiotrophoblast (Tpbpa), syncytial trophoblast (LepR), glycogen (Pchdh12), fetal vascular (Mest) and trophoblast giant cells (Prl2c2, Prl3b1 and Prl3d1) respectively.

Stereology and Morphometrics

All images of placental tissue sections were taken using a DMI4000B inverted microscope (Leica). Morphometric area measurements were made using the Image J (NIH) grid tool. Labyrinth and spongiotrophoblast areas were determined using random grid sampling within 2–3 central 50x or 16x fields of view of H&E stained sections for E12.5 and E15.5 placentas. Labyrinth and central volumes were calculated as the integral of area across the known distance between central H&E stained sections. Area and volume measurements were confirmed by analysis of adjacent slides stained by ISH of lineage markers. Trophoblast giant cell count measurements were from 2–3 central 10μm DAPI stained sections. The average cell count per slide was used as the reported metric. The identity of trophoblast giant cells was confirmed with ISH of adjacent sections.

Methylation Analysis

Methylation analysis of imprinted gDMDs was carried out on all intact placentas for which non-degraded genomic DNA was recovered irrespective of fetal viability. Both DNA and RNA were purified using an AllPrep kit from Qiagen. Genomic bisulfite conversion, bisulfite converted genomic PCR, and EpiTYPER (TM—Sequenom) mass-array DNA methylation analysis was performed at the Center for Genetics and Pharmacology at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Pre-validated bisulfite PCR primers for imprinted gDMD genomic regions were used for the imprinted methylation analysis (S1 Table). All bisulfite amplicon sequences overlapped known primary imprinted gDMDs ([2], and references therein). Bisulfite converted PCR amplification primers for all but H19 were chosen from a publicly available mouse imprinted panel (Sequenom). H19 primer sequences were originally published by McGraw et al. (2013) [32]. Each EpiTYPER amplicon was validated by our internal control wild-type placenta DNA (50% imprinted gDMD methylation), Dnmt1-null (Dnmt1 c/c) ES cell DNA (0% imprinted gDMD methylation) and 1:2 (16.6% imprinted gDMD methylation) and 2:1 (33.3% imprinted gDMD methylation) mixtures of the two. Only amplicons that produced a linear relation between control genomic DNA expected and observed methylation fractions were selected for use in this study.

Biostatistics and Bioinformatics

EpiTYPER absolute methylation levels were calculated as the unweighted average CpG methylation fraction across each individual imprinted gDMD amplicon. Overall imprinted gDMD methylation was determined from 12 non-redundant gDMD EpiTYPER amplicons (S1 Table) To determine if the wild-type and mutant sample methylation levels were normally distributed Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk and Anderson-Darling tests of normality were applied to the data in SPSS (IBM) and Matlab (Mathworks). Because the mutant data were non-normally distributed we compared distributions using a Mann-Whitney U (Rank-Sum) test. Bar graphs and scatter plots of overall and individual imprinted gDMD methylation levels were originally generated with SPSS and Matlab and then adapted into Adobe Illustrator.

To display the variability in gDMD methylation intrinsic to the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model we constructed heat maps. Mutant imprinted gDMD methylation levels were normalized to wild-type by dividing each sample’s imprinted gDMD absolute methylation fraction by the average wild-type methylation level for that imprinted gDMD and gestational age. The relative methylation levels were then log2 transformed and clustered using the clustergram function in Matlab. Each clustergram was adapted into a grey-scale Adobe Illustrator file.

Mean mutant and wild-type phenotypic averages were calculated. The phenotypic data was also subdivided into dead/alive and male/female subgroups to determine the influence of fetal viability and sex on placental phenotypes. Because the mutant phenotypic data were non-normally distributed the Mann-Whitney U (Rank-sum) test was used to compare the distribution of mutant and wild-type phenotypes as well as the phenotypes observed in subgroups. Phenotypic data is displayed in charts showing mean + SEM.

To associate individual placental gDMD methylation defects with particular placental phenotypic abnormalities we performed regression analyses in Matlab. Logistic regression was performed to find associations between individual imprinted gDMD methylation levels and the binary fetal viability variable. Bivariate linear regression analysis was used to associate imprinted gDMDs with the continuous phenotypic metrics for labyrinth volume, spongiotrophoblast volume, trophoblast giant cell count and fetal/placental weights. Stepwise forward linear regression modeling was performed to generate models that explain the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect phenotypic variation based on DNA methylation of the least number of significant gDMDs. To visually confirm strong associations (P<0.05) identified by bivariate regression we plotted placental phenotypic metrics against gDMD methylation.

Results

Imprinted gDMD methylation analysis

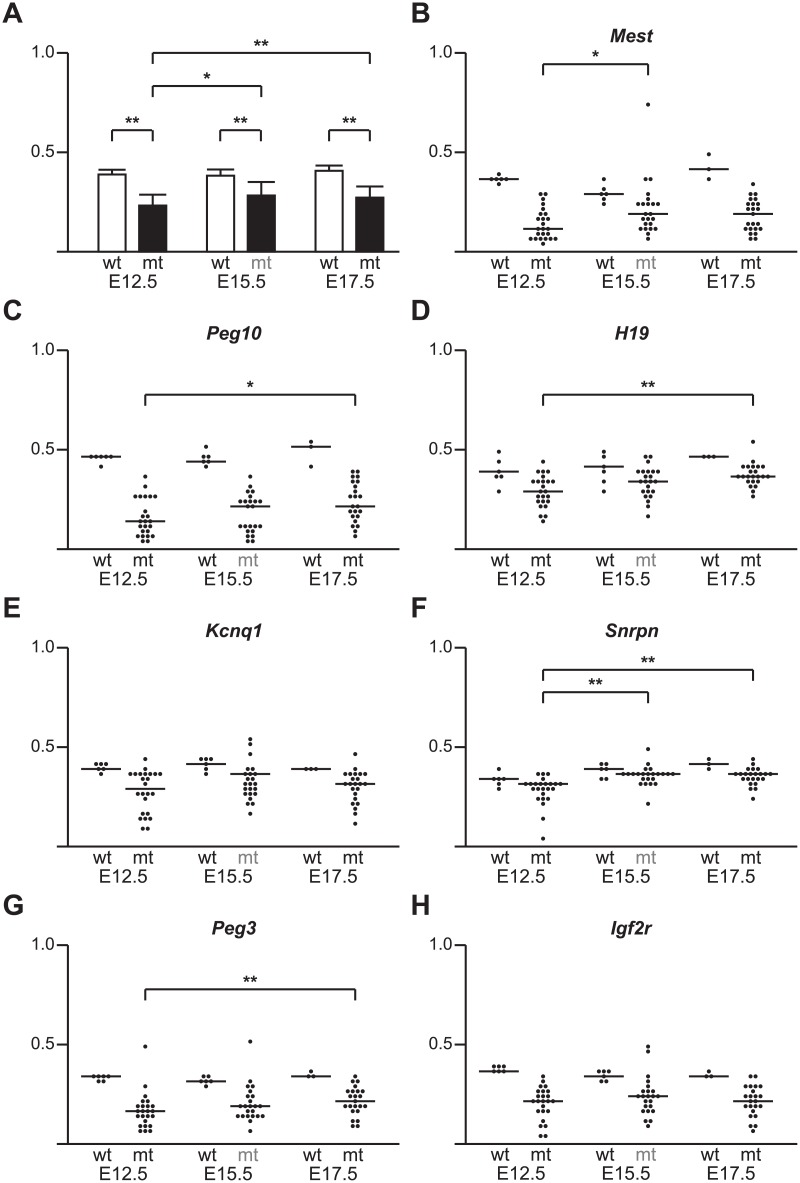

To understand the role of imprinted methylation on the wide-range of placental abnormalities seen in the Dnmt1 Δ1o model, we first measured DNA methylation at 15 imprinted gDMDs at three times during the latter half of gestation (S1 Table). We calculated the average methylation fraction across 12 non-redundant gDMD EpiTYPER amplicons for both wild-type and mutant samples at each time point. Methylation was reduced in DNMT1o-deficient placentas at E12.5, E15.5 and E17.5 (Fig 1A). At E12.5 there was a significant decrease in the average methylation across all gDMDs (P<0.001) from 0.388 for wild-type to 0.232 for mutant placentas. In a collection of 23 E15.5 DNMT1o-deficient placentas, the average gDMD methylation was 0.283, significantly lower than the wild-type average of 0.382 (P<0.001). Similarly in a collection of 24 E17.5 placentas average gDMD methylation was 0.272, significantly lower than the wild-type average of 0.407 (P<0.001). There was a trend toward mutants approaching wild-type levels of imprinted gDMD methylation levels as gestation progressed; average gDMD methylation increased from E12.5 to E15.5 (P<0.01) and from E12.5 to E17.5 (P<0.001) but not from E15.5 to E17.5 (not significant). These findings show that total gDMD methylation levels in DNMT1o-deficient placentas do not remain constant across gestation but rather resolve to more normal levels, suggesting selection against low gDMD methylation epigenotypes that do not support placental development and function.

Fig 1. Imprinted gDMD methylation levels in wild-type (wt) and DNMT1o-deficient (mt) placentas across mid gestation (E12.5, E15.5 and E17.5).

(A) Bar graphs showing average mean and standard deviation of total imprinted gDMD methylation of wt (open bars) and mt (filled bars) across mid-gestation. (B-F) Binned scatter plot showing individual wt and mt placentas across mid-gestation and the sample mean for the following imprinted gDMDs: (B) Mest, (C) Peg10, (D) H19, (E) Kcnq1, (F) Snrpn, (G) Peg3 and (H) Igf2r. Small brackets indicate significant differences between gestational age matched sample populations of wt and mt gDMD methylation medians. Larger brackets indicate significant differences between mutant gDMD methylation medians at different gestational ages. * (P<0.01), and **(P<0.001) denote significant differences of mutant median imprinted gDMD methylation compared to wild type, or between gestational ages of mutant sample population by the Rank-sum test.

As expected, most individual imprinted gDMDs in DNMT1o-deficient placentas were significantly less methylated than gDMDs in wild-type placentas (Fig 1B–1H and S1 Fig). Concomitant with the increasing average imprinted gDMD methylation from E12.5 to E15.5 in DNMT1o-deficient placentas (Fig 1A), we observed a steady reduction in the range of methylation among the examined placentas for many but not all individual gDMDs (Fig 1B–1H and S1 Fig). Based on this, we were able to define three distinct temporal patterns of methylation. A group of five gDMDs had higher average methylation at E15.5 than at E12.5 (Mest, Snrpn, Dlk1.A, Dlk1.B, and Nespas.B; P<0.025; Fig 1B and 1F, S1C, S1D and S1F Fig). Other gDMDs had a more gradual increase in methylation from E12.5 to E17.5 (Peg10, H19 and Peg3; P<0.025; Fig 1C, 1D and 1G). Five gDMDs comprise a third gDMD class that did not significantly change their average methylation across gestation in DNMT1o-deficient placentas (Kcnq1, Igf2r, Plagl1, Nespas.A, Nespas.B, Impact.A and Impact.B; Fig 1E and 1H, S1B and S1E–S1H Fig ). Out of the three imprinted gDMDS for which duplicate adjacent EpiTYPER amplicons were selected (Dlk1, Impact and Nespas), only Nespas showed a discordant trend with Nespas.A not differing between gestational cohorts and Nespas.B transitioning to higher average methylation between E12.5 and E15.5 (S1C–S1H Fig). Additionally the Grb10 gDMD displayed opposing changes from E12.5 to E15.5 and E15.5 to E17.5, and did not significantly differ between E12.5 and E17.5 (S1A Fig). Three putative imprinted gDMDs were examined in E12.5 and E15.5 cohorts (Commd1, Nnat and Nap1l5), and only Commd1 had a significant difference between wild-type and the Dnmt1 Δ1o mutant average methylation levels (S2 Fig). In DNMT1o-deficient placentas Commd1 remained variable and did not differ between E12.5 and E15.5. Overall, the observed trends in gDMD methylation during gestation suggest that there are strong biological influences blocking the loss of imprints at specific gDMDs during mid-gestation.

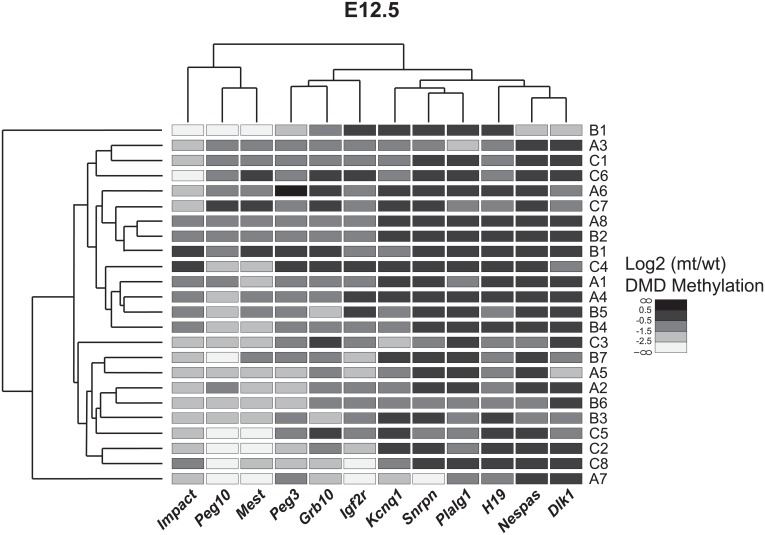

The spectrum of methylation among 12 gDMDs for each individual E12.5 DNMT1o-deficient placenta is displayed in the form of a heat map clustergram (Fig 2). Among the 24 E12.5 placentas represented in this manner, the majority of placentas have a unique gDMD methylation profile not found in other placentas, although there are a few cases of high similarity. For example placentas A8 and B2 have identical gDMD methylation profiles. Placentas A4 and B5 differ only at Grb10, Kcnq1 and H19 gDMDs, and placentas A3 and C1 are unique at only the Plagl1 gDMD. Clustering of the gDMDs at E12.5 indicate the genetically linked Peg10 and Mest gDMDs as well as the linked Kcnq1 and Snrpn gDMDs vary in conjunction. Although there is a trend toward more normal gDMD methylation levels at E15.5 and E17.5, each DNMT1o-deficient placenta at these stages still has a unique imprinted epigenotype (S3 and S4 Figs). These comparisons among placentas across the latter half of gestation point out the intrinsic power of the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model to produce diverse and abnormal patterns of imprinted gDMD methylation.

Fig 2. Hierarchical clustering of 24 E12.5 DNMT1o-deficient placentas based on gDMD methylation.

Data is shown as the log2 transformed ratio of mt:wt gDMD methylation. The heat map displays normally methylated gDMDs as dark boxes whereas loss of methylation is indicated by lighter shades. The upper and side dendrograms display linkage between imprinted gDMDs and DNMT1o-deficient samples respectively. Imprinted gDMDs are labeled across the bottom axis. DNMT1o-deficient samples are labeled down the right hand side by cohort litter (Letters A-C) and conceptus (Numbers 1–8).

Fetal viability is associated with gDMD methylation

DNMT1o-deficient placentas were collected at three gestational time points (E12.5, E15.5 and E17.5) and their phenotypic and epigenetic abnormalities described. A significant number of intact and viable placentas were associated with a deceased fetus at each time point. At E12.5 litter sizes of Dnmt1 Δ1o/ Δ1o dams were consistent with wild-type litters (average of eight conceptuses), although slightly more than half of the conceptuses contained dead embryos (Table 1). On average smaller numbers of conceptuses were found in litters from Dnmt1 Δ1o/ Δ1o females at E15.5 and E17.5. At these two later gestational times however, we recovered a greater percentage of conceptuses with an intact placenta and live fetus (Table 1). All placentas that were not obviously necrotic produced intact genomic DNA for methylation analysis whether or not they were associated with a live fetus.

Table 1. Viability of mid-gestation DNMT1o-deficient conceptuses.

Viability of litters collected at mid-gestation in this study.

| Gestational Age (dpc) | # Litters | #Placentas(a) | #Live Embryos(b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E12.5 | 3 | 24 | 10 |

| E15.5 | 4 | 23 | 11 |

| E17.5 | 5 | 23 | 14 |

a) Only intact (non-necrotic) placentas were counted. b) Embryo viability based on presence of active circulation. DPC—days post copulation.

Logistic regression was used to identify those imprinted gDMDs that exerted the greatest influence on fetal viability at E12.5 through placental imprinting (Table 2). We report the logistic regression coefficient (logit) as a measure of the effect of DMD methylation levels on the odds ratio of fetal survival. A positive association was discovered between Peg10 gDMD methylation and fetal viability at E12.5 (P<0.05) indicating that placentas with loss of the Peg10 methylation imprint are less likely to support a viable fetus. A negative association between Nnat gDMD methylation and fetal viability was observed (P<0.05). The only significant association identified between imprinted gDMD methylation and fetal viability at either E15.5 or E17.5 was a negative association between Nespas.B gDMD methylation and viability at E15.5 (P<0.05; S3 and S4 Tables). These findings suggest that in the context of the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect mouse model, nearly normal Nnat and Nespas imprinting may decrease viability.

Table 2. Bivariate regression analysis of E12.5 DNMT1o-deficient placentas based on gDMD methylation and placental phenotypes.

Only significant (P<0.05) associations established by bivariate regression analysis between dependent placental phenotypes and independent imprinted gDMD methylation values are shown. Regression coefficient is either the logit (log odds ratio) for logistic regression for fetal viability, or the linear regression coefficient (β) for all other variables.

| Placental Phenotype | Imprinted gDMD | Regression Coefficient | Significance (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Viability | Peg10 | 2.17 | 3.25E-02 |

| Nnat | -2.49 | 4.12E-02 | |

| Placental Weight (mg) | Nespas.A | -127.5 | 6.21E-04 |

| Spongiotrophoblast Central Volume (mm3) | Nespas.A | -3.99 | 1.41E-05 |

| Nespas.B | -2.65 | 3.54E-02 | |

| H19 | -1.7 | 4.08E-02 | |

| Labyrinth Central Volume (mm3) | Peg10 | 3.58 | 3.12E-02 |

| Nnat | -7.72 | 2.82E-04 | |

| Trophoblast Giant Cell Count (#/section) | Kcnq1 | -508 | 1.87E-05 |

| Snrpn | -674 | 2.31E-04 | |

| Plagl1 | -438 | 1.97E-02 | |

| Nespas.B | -575 | 4.38E-02 |

Placental abnormalities are associated with loss of gDMD methylation

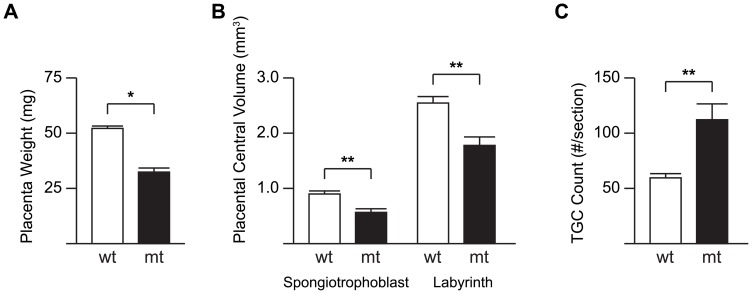

DNMT1o-deficient and wild-type placentas differed in many ways at E12.5, particularly in weight, central spongiotrophoblast volume, central labyrinth volume and number of TGCs (Fig 3). There was a trend toward decreased placental weight in DNMT1o-deficient placentas (P<0.05; Fig 3A). Additionally there were significant decreases in measured central labyrinthine volume (P<0.005; Fig 3B) and central spongiotrophoblast volume (P<0.005; Fig 3B) in the DNMT1o-deficient placentas compared to wild-type controls. A marked increase in the number of TGCs per central section was measured in the E12.5 DNMT1o-deficient placentas compared to wild-type controls (P<0.01; Fig 3C). These findings are in line with our previous reports of distorted placental layer development at E9.5 (30).

Fig 3. Phenotypic comparison of wild-type (wt) and DNMT1o-deficient (mt) placentas at E12.5.

(A) Measurements of wet placenta weight, (B) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume, and (C) the number of TGCs per slide of a cohort of wt and mt placentas are displayed as open and filled bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean +SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt and mt averages by the Rank-sum test.

To determine the effects of fetal viability and sex on placental phenotypes in the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect mouse model we compared live/dead and male/female mutant and wild-type cohorts (S5 and S6 Figs). We compared the phenotypes of DNMT1o-deficient placentas that harbored live and dead fetuses and found that those placentas that did not support a viable fetus had less labyrinth volume than those that did support a live fetus. In a sex comparison of DNMT1o-deficient placentas we discovered that female placentas on average had smaller central labyrinth volumes than mutant males (P<0.05; S6B Fig). In addition, DNMT1o-deficient females had significant differences from wild-type counterparts at all measured phenotypes whereas mutant males only differed from wild-type males in labyrinth central volume and TGC number. These results are in line with previously reported exacerbated early placental phenotypes in female offspring from the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect mouse model [32].

The variability in phenotypic metrics observed at E15.5 was smaller than that seen at E12.5. Specifically, at E15.5 neither spongiotrophoblast central volume nor labyrinth central volume phenotypic metrics significantly differed between wild-type and mutant cohorts (S7C Fig). However, there was an increase in both placental and fetal weights in DNMT1o-deficient placentas compared to gestational age matched controls (S7A and S7B Fig). We found in our comparison of live and dead mutants (S8 Fig) that viable DNMT1o-deficient placentas and fetuses were overgrown (P<0.005; S8A and S8B Fig). Mutant female placentas weighed more than wild-type females (P<0.05) but males did not differ from their wild-type counterparts (S9A Fig). Furthermore we analyzed placental and fetal weights at E17.5 and found that those placentas recovered at E17.5 were overgrown (P<0.005; S10A Fig). Conceptuses supporting live fetuses harbored heavier placentas (P<0.005) and fetuses (P<0.005) than those that were not viable (S11A and S11B Fig). Both male and female mutant placentas were heavier than wild-type controls (P<0.005 and P<0.05; S12A Fig).

Because of the broader range of abnormal gDMD methylation, histomorphological abnormalities and effects on fetal viability at E12.5 we focused our detailed phenotype-epigenotype regression analysis on the E12.5 time point. Bivariate linear regression analysis was used to determine which imprinted gDMDs underlie the observed E12.5 placental abnormalities. The most significant (P<0.05) gDMD associations for each phenotype are displayed in Table 2 and S13 and S14 Figs We report the regression coefficient (β) as the change in phenotype associated with modulation of the gDMD methylation fraction (0 to 1.0). Placenta weight is negatively associated with gDMD methylation at Nespas.A (Table 2 and S13A Fig) although not at Nespas.B. For each 1% decrease in Nespas.A gDMD methylation (0.01 methylation fraction) placental weight increased by a corresponding 1.275 milligrams (95% CI: 0.648, 1.902). Spongiotrophoblast volume was negatively associated with both analyzed Nespas regions as well as the H19 gDMD (Table 2 and S13B–S13D Fig). Each 1% decrease in gDMD methylation at Nespas.A, Nespas.B and H19 increased spongiotrophoblast volume by 0.0399 (95% CI: 0.0258, 0.054), 0.0266 (95% CI: 0.035, 0.0497) and 0.0170 (95% CI: 0.0017, 0.0323) mm3 respectively.

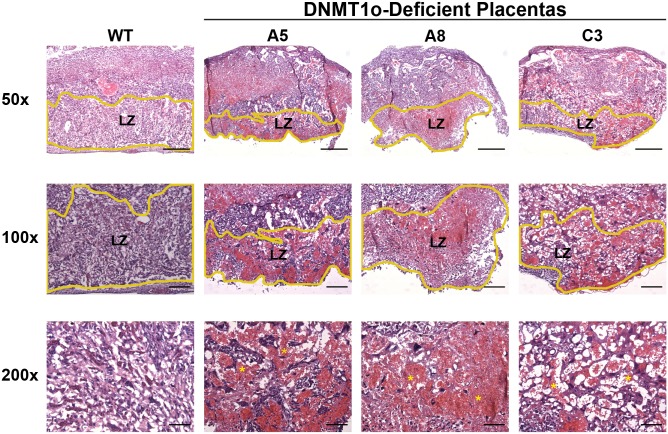

Linear regression analysis revealed a strong association between Peg10 gDMD methylation and labyrinth volume (Table 2, S13E Fig). Diminishment of Peg10 gDMD methylation by 1% corresponds to a 0.0217 (95% CI: 0.002, 0.066) mm3 decrease in labyrinthine central volume. Labyrinth structures in three DNMT1o-deficient placentas with low Peg10 gDMD methylation are shown in Fig 4. Labyrinths in these samples are noticeably smaller, disorganized and hemorrhagic. Notably, methylation of the Nnat gDMD is negatively associated with labyrinth volume (Table 2 and S13F Fig), counter to the observed trend of decreased labyrinth in DNMT1o-deficient placentas; a 1% decrease in Nnat gDMD methylation resulting in a 0.0249 (95% CI: 0.043, 0.111) mm3 increase in labyrinth central volume.

Fig 4. Histology of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained labyrinth of one wild-type (wt) three DNMT1o-deficient low-Peg10 gDMD methylation placentas.

The scale bars for 50X, 100X and 200X magnification are 500, 200 and 100 μm respectively. Yellow lines in 50x and 100x magnification images outline the labyrinthine zone (LZ).

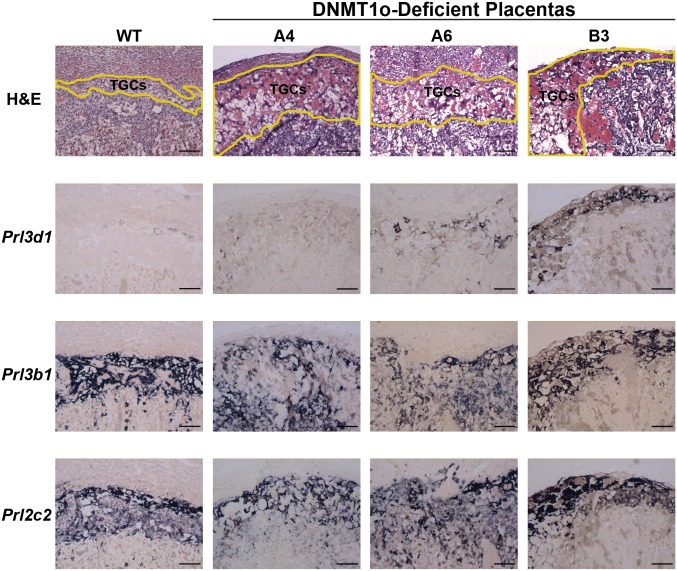

Bivariate regression analysis revealed a significant negative association between Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and accumulation of TGCs (Table 2 and S14A Fig). A 1% decrease in Kcnq1 gDMD methylation corresponds to an increase of 5.08 (95% CI: 3.25, 6.91) TGCs per histological section. Representative H&E and ISH stained histological sections of wild-type and DNMT1o-deficient placentas with very low Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and pronounced expansion of parietal TGCs bordering the spongiotrophoblast are displayed in Fig 5. Positive ISH staining for the pan-TGC transcripts proliferin (Plf; Prl2c2) and Prolactin-2 (Pl2; Prl3b1) was observed in both parietal TGCs and spongiotrophoblast layers (Fig 5). Intriguingly, the early TGC marker Prolactin-1 (Pl1; Prl3d1) was ectopically expressed in the parietal TGCs of DNMT1o deficient placentas with low Kcnq1 gDMD methylation, whereas it should be restricted to TGCs embedded within maternal spiral arteries by E12.5.

Fig 5. In situ hybridization analysis of TGCs in E12.5 wild-type and DNMT1o-deficient placentas with low Kcnq1 gDMD methylation.

All images were taken at 100X magnification. The scale bar is 100μm. Yellow lines delineate the layer containing trophoblast giant cells (TGCs) in the top row displays histology of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections. ISH for the prolactin gene family members Prl3d1, Prl3b1 and Prl2c2 on adjacent sections to H&E are shown in the lower three rows.

DNA methylation at the genetically linked Snrpn gDMD (both Kcnq1 and Snrpn gDMDs are on mouse chromosome 7) also inversely associated with TGC accumulation (Table 2 and S14B Fig). For every 1% decrease in Snrpn gDMD methylation there is a corresponding increase of 6.74 (95% CI: 3.73, 9.75) TGCs per section. A weaker inverse association between both Plagl1 and Nespas.B gDMD methylation and TGC number was also identified (Table 2 and S14C and S14D Fig). Decreases of 1% methylation at Plagl1 and Nespas.B modulate an increase in TGCs per section of 4.38(95% CI: 0.970, 7.79) and 5.75(95% CI: 0.500, 11.0) respectively. Imprinted DNA methylation at the Peg3 gDMD, which like Kcnq1 and Snrpn is a maternally derived methylation imprint on mouse chromosome 7, was not significantly associated with TGC accumulation (P = 0.40). Linear regression model building confirmed the major gDMD methylation influence of TGC accumulation to that of just the Kcnq1 and Snrpn gDMDs (S2 Table).

To determine if there were any phenotype-epigenotype assocations at E15.5 and E17.5 we performed bivariate linear regression. At E15.5 spongiotrophoblast central volume inversely associated with Impact.B and Mest methylation (P<0.05; S3 Table). Each 1% decrease in Impact.B and Mest methylation increased spongiotrophoblast central volume by 0.0717 (95% CI: 0.043, 0.1004) and 0.0449 (95% CI: 0.0275, 0.0623) mm3 respectively. Using a relaxed significance threshold we found only three meaningful phenotype-epigenotype associations at E17.5 (P<0.075; S4 Table). Placental weight was positively associated with Dlk1.A methylation: each 1% decrease in Dlk1.A methylation corresponded to a 1.166 (95% CI: 0.591, 1.741) milligram decrease in placental weight. Fetal weight was associated with placental methylation at the Igf2r and Mest gDMDs: for each 1% decrease in Igf2r and Mest methylation fetal weight decreased by 20.40 (95% CI: 11.17, 29.63) and 16.81 (95% CI: 8.05, 25.57) milligrams respectively.

Discussion

Results presented here and in our prior work [31] provide unequivocal evidence in support of the importance of imprinted gDMD methylation during placental development. In this study we ascribed placental function for gDMDs in two ways: by identifying nearly normal gDMD methylation in DNMT1o-deficient placentas; and by correlating highly variable gDMD methylation with placental phenotypes at E12.5. We expected total wild-type placental gDMD methylation to be approximately 50%, but found the wild-type average to be just under 40% at each time point. These results are consistent with the slightly lower levels of gDMD methylation found in control placentas than embryos in prior studies [32]. Our results show a large range of methylation across individual gDMDs with Peg3 (32.7%) on the low end and Dlk1.A (57.7%) on the high end in wild-type E12.5 samples. Based on our understanding of DNMT1o action it is predicted that on average a 50% loss of methylation at each gDMD should be observed in cohorts of DNMT1o-deficient placentas [3–5]. However, we found that a few imprinted gDMDs were nearly normally methylated at E12.5 (i.e. H19, Dlk1.A, Dlk1.B and Nespas.B; Fig 1D, S1C, S1D and S1F Fig) and E15.5 (ie. H19, Snrpn, Dlk1.A, Dlk1.B, and Nespas.B; Fig 1D and 1F, S1C, S1D and S1F Fig). These findings suggest that many epigenotypes with these gDMDs poorly methylated may be incompatible with early trophoblast survival and/or proliferation resulting in selection against specific epigenotypes at the cellular and organismal level.

Interrogation of the association of gDMD methylation and placental phenotypes by regression analysis confirmed the importance of gDMD methylation in placental development and function. Herein, significant associations were observed between diminished imprinted methylation of the variable gDMDs (Peg10, Kcnq1, H19 and Nespas) and specific placental phenotypes in DNMT1o-deficient E12.5 placentas (Table 2; S13 and S14 Figs). Importantly, this approach using the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model to gain insight into the role of imprinted genes in placental development and function is fundamentally different in two significant ways from genetic approaches that inactivate either single imprinted genes or remove imprinting control centers. First, the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model produces epigenetic mutant offspring with loss of gDMD methylation, while retaining the genetic sequence of ICRs and imprinted genes. Second, the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model produces broadly variable methylation effects across many gDMDs. This permits gDMD methylation to be treated as a continuous variable in a quantitative trait analysis, thus revealing strong associations between loss of methylation at particular gDMDs and histo-morphological placental phenotypes. The recognition of these associations offers new insights into the integral role of genomic imprints in placenta development.

Peg10 Viability and Labyrinth Phenotypes

A strong association was observed between loss of Peg10 gDMD methylation and decreased fetal viability and labyrinth volume at E12.5 (Table 2 and S13 Fig). Most placentas with loss of Peg10 gDMD methylation and decreased labyrinth volume were unable to support fetal development. We interpret these associations, and the gradual trend toward normal Peg10 gDMD methylation levels from E12.5 to E17.5 (Fig 1C), as a progressive requirement for Peg10 methylation to sustain fetal viability during later gestation. The decreasing Peg10 gDMD methylation variability and lack of phenotypic association at E15.5 and E17.5 could be explained by selection against certain low Peg10 gDMD methylation epigenotypes. The gDMD methylation epigenotype of placentas with low Peg10 methylation at E12.5 is different than the epigenotype of placentas with low Peg10 gDMD methylation recovered at E15.5 and E17.5 (Fig 2, S4 and S7 Figs). The combination of low Peg10 gDMD methylation (<50% wild-type level) plus low Dlk1, Kcnq1, Nespas or Snrpn gDMD methylation (<50% wild-type) was observed at E12.5 (samples A5, A7, B1 and C3; Fig 2) but does not occur in any DNMT1o-deficient placentas at either E15.5 or E17.5 (S3 and S4 Figs). In summary, our analysis of DNMT1o-deficient placentas reveals a novel link between placentas with low Peg10 gDMD methylation, poor labyrinth development and the inability to sustain fetal development.

We found a strong linkage between Mest and Peg10 gDMD methylation at E12.5 and E17.5 (Fig 2 and S7 Fig). This was expected given the proximity of the two gDMDs on mouse chromosome 6, however Mest did not show significant associations with early placental phenotypes in this study. This observation does not preclude a role for Mest later in gestation, and in fact we previously discovered a link between loss of Mest gDMD methylation and placental lipid accumulation at E17.5 [35]. In our current study we found an inverse association between Mest gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume at E12.5 (S3 Table) and a positive association between Mest and fetal weight at E17.5 (S4 Table). We suggest that Mest and Peg10 gDMDs may exert their influence on placental development in a serial manner; loss of Peg10 gDMD methylation impairs labyrinth development early in gestation, which predisposes these placentas to metabolic abnormalities associated with lost Mest gDMD methylation later in gestation.

The lethality and labyrinth failure in DNMT1o-deficient placentas with low Peg10 gDMD methylation is similar to the phenotype observed in Peg10 null mice [27]. Although the expected result of loss of Peg10 gDMD methylation is increased Peg10 expression, we previously failed to detect significant changes in Peg10 expression in DNMT1o-deficient placentas at any time point between E9.5 and E17.5 [31]. However, we did previously observe a significant increase in Sgce and Pon2 expression in late gestation DNMT1o-deficient placentas [31]. It is difficult to correlate gDMD methylation with imprinted gene expression in Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect placentas because of the confounding factors of a mosaic model, cell-type expression biases and differential effects of loss of gDMD methylation. Based on our direct observation that partial loss of a maternally methylated Peg10 imprint is detrimental to placental development, we suggest that strict monoallelic dosage of Peg10, and/or other imprinted genes within the Peg10 imprinted cluster is critical for placental development.

Loss of Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and TGC expansion

Mouse chromosome 7 contains one paternally (H19) and three maternally (Kcnq1, Snrpn and Peg3) methylated gDMDs. Not surprisingly, we found that the methylation status of the Kcnq1 and Snrpn gDMDs was linked at E12.5 in DNMT1o-deficient placentas (Fig 2). A strong association between DNA methylation at these two gDMDs and accumulation of TGCs was unearthed (Table 2 and S14 Fig). Based on our forward step-wise regression model (S2 Table) the combination of gDMD methylation levels of Kcnq1 and Snrpn is the best predictor of TGC abundance. We speculate that the association between Snrpn methylation and TGC accumulation is a passive effect due to close linkage with the Kcnq1 cluster and consistent with lack of known placental function for Snrpn [12]. The in situ staining of TGCs for Prl3d1 in DNMT1o-deficient placentas, an early TGC marker, indicates that not only is proliferation altered but also TGC differentiation (Fig 5). The morphology of DNMT1o-deficient placentas with low Kcnq1 gDMD methylation is similar to those described in null and hypomorphic Ascl2 (a maternally expressed transcription factor and member of the Kcnq1 cluster) mouse models in which expansion of TGCs was observed [14, 36]. It has previously been demonstrated that DNMT1o-deficient placentas have decreased expression of Ascl2 [31, 37]

The accumulation of TGCs observed in the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model shown herein is remarkably similar to placentas derived from Dnmt3L null mothers, which lack all maternal imprinted gDMD methylation [38, 39]. One mechanistic explanation of the TGC expansion that is common between the Dnmt1 Δ1o, Dnmt3L and Ascl2 models is that a decrease in Ascl2 expression (by gene deletion or loss of Kcnq1 gDMD methylation) results in derepression of Hand1, a transcription factor that promotes differentiation of the ectoplacental cone and spongiotrophoblast into TGCs [40–42]. Loss of Kcnq1 gDMD methylation in DNMT1o-deficient placentas has a distinct phenotype from paternal deletion of the Kcnq1 ICR, which mimics a maternal (methylated) state with resulting increased maternal expression of Ascl2, Phlda2, and Cdkn1c, and growth restriction [43]. Regression analysis did not reveal meaningful associations between loss of Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and placental overgrowth at E15.5 or E17.5 that might be expected based on targeted deletion mouse models of Phlda2 and Cdkn1c, which exhibit pronounced placental overgrowth [15, 16]. Our findings taken together with prior research suggest that the imprinted gene Ascl2 is a focal point for early placental development.

Loss of Nespas and H19 gDMD and spongiotrophoblast development

In addition to the effects of reduced Peg10 and Kcnq1 gDMD methylation discussed above, this study revealed weaker, but nonetheless significant, associations between loss of imprinted Nespas and H19 gDMD methylation and increased spongiotrophoblast volume (Table 2 and S13B–S13D Fig). Although both Nespas gDMD amplicons assayed associated significantly with spongiotrophoblast expansion at E12.5 (Table 2, S13B and S13C Fig), an association was not observed at E15.5 (S3 Table), indicating this phenotype may resolve to a more normal one during development.

The observed association between loss of H19 gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast expansion bordered the significant cutoff (P = 0.048, Table 2 and S13D Fig). H19 gDMD methylation gradually increased from E12.5 to E17.5 in DNMT1o-deficient placentas, indicating selection against loss of imprinting at this cluster. Loss of methylation at the H19 gDMD is expected to depress transcription of the growth factor Igf2. We previously described loss of Igf2 expression in DNMT1o-deficient placentas at in E9.5 and E12.5 but found more normal levels at E15.5 and E17.5 [31]. It is known that Igf2 is paternally expressed throughout the placenta, and that the placenta specific isoform (Igf2P0) is expressed exclusively in labyrinth syncytiotrophoblast [20, 21]. Paternal inheritance of either the Igf2 null or Igf2P0 null allele results in placenta with reduced spongiotrophoblast volume [21]. Based on this knowledge one explanation for the observed trend is that spongiotrophoblast is less dependent on IGF2 signaling than labyrinthine cell types, and may increase as an early compensatory mechanism to low placental Igf2 expression. The association between H19 gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume is not found at E15.5 reflecting the resolving of both H19 methylation levels and spongiotrophoblast volume toward normal levels.

Associations of placental phenotype and Dlk1, Igf2r and Grb10 gDMD methylation not found

At the onset of this study we expected to find associations between imprinted DNA methylation at the Dlk1 gDMD and labyrinth development, and between both the Grb10 and Igf2r gDMDs and placental growth based on evidence from genetic models [23, 24]. In DNMT1o-deficient placentas imprinted DNA methylation at the Dlk1 gDMD did not significantly differ from wild-type although it did increase across gestation (S1C and S1D Fig). This pattern is perhaps indicative of early selection against cellular epigenotypes with loss of Dlk1 gDMD methylation during trophoblast differentiation and proliferation. We did not find associations between Dlk1 gDMD methylation and placental phenotypes at E12.5 and E15.5, but did find a positive association between Dlk1.A methylation and placental weight at E17.5 (S4 Table), indicating loss of Dlk1 methylation restricts placental growth. Although there was substantial variation in gDMD methylation at the Igf2r and Grb10 gDMDs (Fig 1H and S1A Fig), we did not find direct associations between placental weight and gDMD methylation at either loci at E12.5 or E15. However, we discovered a positive relationship between Igf2r gDMD methylation and fetal weight at E17.5 (S4 Fig), a counter intuitive finding given that loss of Igf2r methylation should repress expression of this growth suppressor. Regression analysis failed to identify gDMDs responsible for the overgrowth of late gestation placentas and embryos but rather identified ones that promoted growth restriction. We interpret these results as evidence that in the context of the Dnmt1 Δ1o mosaic loss-of-imprinting model, the mid to late gestation growth effects of the Grb10 and Igf2r gDMDs may be obscured by epigenetic epistatic interactions with loss of imprinting at other prominent gDMDs within both placental and embryonic compartments. The clinically relevant dysregulation of placental and fetal growth associated with loss of imprinting previously highlighted (31) and confirmed herein is likely due to these complex interactions between imprinted regions. In contrast, the stronger associations between both Peg10 and Kcnq1 and E12.5 placental phenotypes were not occluded by confounding epistatic effects.

Commd1 is an imprinted gDMD in placenta but Nnat and Nap1l5 are not

We measured the DNA methylation levels of three additional imprinted gDMDs (Commd1, Nnat and Nap1l5) in wild-type and DNMT1o-deficient E12.5 and E15.5 placentas (S2 Fig). The mouse genomic coordinates for these three gDMDs were previously established [2], but were not examined in placenta. EpiTYPER analysis showed that the Commd1 gDMD was methylated at a level consistent with imprinting in wild-type placenta, which was then lost in DNMT1o-deficient placentas (S2A Fig). Both the Nnat and Nap1l5 gDMDs showed a methylation pattern that was not indicative of imprinted gDMDs (S2B and S2C Fig). Both gDMDs also had higher methylation levels in wild-type placentas than other imprinted gDMDs tested (gDMD methylation fraction >0.7), and furthermore, neither gDMD lost methylation in DNMT1o-deficient placentas. We conclude that neither Nnat nor Nap1l5 are imprinted gDMDs that are perpetuated from gametes to mature trophoblast lineages, and that although the Commd1 gDMD is imprinted in the placenta, loss of imprinting at this loci is tolerated. Recent genome methylation studies have provided evidence that the Nap1l5 but not the Nnat gDMD retains its imprinted status in the human placenta [44, 45].

Conclusion

In summary, we have validated the epigenetic variability inherent in the Dnmt1 Δ1o maternal effect model using a broad survey of imprinted gDMD methylation. We discovered a novel association between loss of imprinting at the Peg10 loci and fetal viability and placental labyrinth maldevelopment. In addition we found a strong association between loss of imprinting at the Kcnq1 cluster and TGC accumulation, validating prior genetic models. We conclude from the lack of Dlk1 gDMD methylation variability at E12.5 that Dlk1 has an essential early trophoblast function. This study highlights the direct epigenetic effects of loss of imprinting on placenta development. Our findings provide additional rationale to further dissect the Peg10 and Kcnq1 imprinting clusters for their roles in placental development.

Supporting Information

Binned scatter plot showing individual wt and mt placenta across mid-gestation and the sample mean for the following imprinted gDMDs: (A) Grb10, (B) Plagl1, (C) Dlk1.A, (D) Dlk1.B, (E) Nespas.A, (F) Nespas.B, (G) Impact.A and (H) Impact.B. Brackets indicate significant differences between mutant gDMD methylation medians at different gestational ages. * (P<0.01) and **(P<0.001) denote significant differences of mutant median imprinted gDMD methylation compared to wild type, or between gestational ages of mutant sample population by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

Data displayed as binned scatter plots showing individual wt and mt placentas across mid-gestation and the sample mean for the following imprinted gDMDs: (A) Commd1, (B) Nnat, (C) and Nap1l5. No significant changes in gDMD methylation levels between mt cohorts at E12.5 and E15.5 were detected by the Rank-Sum test.

(PDF)

Data is shown as the log2 transformed ratio of mt:wt gDMD methylation. The heat map displays normally methylated gDMDs as dark boxes whereas loss of methylation is indicated by lighter shades. The upper and side dendrograms display linkage between imprinted gDMDs and DNMT1o-deficient samples respectively. Imprinted gDMDs are labeled across the bottom axis. DNMT1o-deficient samples are labeled down the right hand side by cohort litter (Letters A-D) and conceptus (Numbers 1–8).

(PDF)

Data is shown as the log2 transformed ratio of mt:wt gDMD methylation. The heat map displays normally methylated gDMDs as dark boxes whereas loss of methylation is indicated by lighter shades. The upper and side dendrograms display linkage between imprinted gDMDs and DNMT1o-deficient samples respectively. Imprinted gDMDs are labeled across the bottom axis. DNMT1o-deficient samples are labeled down the right hand side by cohort litter (Letters A-G) and conceptus (Numbers 1–8).

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume, and (C) the number of TGCs per slide of wt, mt-live and mt-dead placental cohorts are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume, and (C) the number of TGCs per slide of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female placental cohorts are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denotes significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt and mt cohorts are displayed as open and filled bars respectively. Data are displayed as mean + SEM. * (P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt and mt averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt, mt-live and mt-dead cohorts are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female cohorts are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denotes significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placental weights and (B) Wet fetal weights of wt and mt cohorts are shown as open and filled bars respectively. Data are displayed as mean +SEM. ** (P<0.001) by the Rank-Sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight and (B) Fetal weight of wt, mt-live and mt-dead conceptuses are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, and (B) Wet fetal weight, of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female conceptuses are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Negative association between Nespas.A gDMD methylation and placental weight. (B) Negative association between Nespas.A gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (C) Negative association between Nespas.B gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (D) Negative association between H19 gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (E) Positive association between Peg10 gDMD methylation and labyrinth volume. (F) Negative association between Nnat gDMD methylation and labyrinth volume. R2 is unadjusted R-square value.

(PDF)

(A) Negative association between Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (B) Negative association between Snrpn gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (C) Negative association between Plagl1 gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (D) Negative association between Nespas.B gDMD methylation and TGC counts. R2 is unadjusted R-square value.

(PDF)

Forward and Reverse sequence tags attached to each primer pair for EpiTYPER methylation analysis. Genomic coordinates of imprinted gDMDs from the most recent mouse genome build (GRCm38). Imprinted gDMD amplicons in bold were those used to calculate average imprinted gDMD methylation fraction in Fig 1A.

(PDF)

N = 24, df = 21, model P-value = 1.54x10-5.

(PDF)

Only significant (P<0.05) associations are shown. Regression coefficient is either the logit (log odds ratio) for logistic regression for fetal viability, or the linear regression coefficient (β) for all other variables.

(PDF)

Only associations with strong (P<0.075) are shown. The linear regression coefficient (β) is reported for both phenotypic variables.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Drs. Y. Barak and Y. Sadovsky for helpful advice and discussions, and Magee-Womens Research Institute Histology Core for assistance with histology.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by P01-HD069316, UL1-RR0241153, and UL1-TR000005, all from the National Institutes of Health USA. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Reinhart B, Paolini-Giacobino A, Chaillet JR. Specific differentially methylated domain sequences direct the maintenance of methylation at imprinted genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006; 26:8347–8356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macdonald W, Mann M. Epigenetic regulation of genomic imprinting from germ line to preimplantation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014; 81:126–140. 10.1002/mrd.22220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cirio M, Ratnam S, Ding F, Reinhart B, Navara C, Chaillet JR. DNA methyltransferase 1o functions during preimplantation development to preclude a profound level of epigenetic variation. BMC Dev Biol. 2008; 8(1), 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howell C, Bestor T, Ding F, Latham K, Mertineit C, Trasler J, et al. Genomic imprinting disrupted by a maternal effect mutation in the Dnmt1 gene. Cell. 2001; 104:829–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cirio M, Martel J, Mann M, Toppings M, Bartolomei M, Trasler J, et al. DNA methyltransferase 1o functions during preimplantation development to preclude a profound level of epigenetic variation. Dev Biol. 2008; 324:139–150 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weksberg R, Shuman C, Smith A. Beckwith-Wiedmann Syndrome. Am J Med Genet C. 2005; 137C:12–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choufani S, Shuman C, Weksberg R. Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Am J Med Genet C. 2010; 153C:343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith A, Choufani S, Ferreira J, Weksberg R. Growth Regulation, Imprinted Genes, and Chromosome 11p15.5. Pediatr Res. 2007; 61:43R–47R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abu-Amero S, Wakeling E., Preece M., Whittaker J., Stanie P, Moore G. Epigenetic Signatures of Silver-Russell Syndrome. 2010. J Med Genet. 47(3) 150–154 10.1136/jmg.2009.071316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abu-Amero S, Monk D, Frost J, Stanier P, Moore G. The Genetic Aetiology of Silver-Russel Syndrome. 2007; J Med Genet. 45:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coan P, Burton G, Ferguson-Smith A. Imprinted Genes in the Placenta—A Review. Placenta. 2005; 26:S10–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frost J, Moore G. The Importance of Imprinting in the Human Placenta. PLoS Genet. 2010; 6(7), e1001015 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobs K, Robinson W and Lefebvre L. Beckwith-Wiedemann and Silver-Russell syndromes: opposite developmental imbalances in imprinted regulators of placental function and embryonic growth. Clin Genet. 2013; 84:326–334 10.1111/cge.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guillemot F, Nagy A, Auerbach A, Rossant J, Joyner A. Essential Role of Mash-2 in Extraembryonic Development. Nature. 1994; 371:333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frank D, Fortino W, Clark L, Musalo R. Wang W, Saxena A, et al. Placental overgrowth in mice lacking the imprinted gene IPL . Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002; 99:7490–7495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tunster S, Van de Pette M, John R. Fetal overgrowth in the Cdkn1c mouse model of Beckwith-Wiedmann Syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2011; 4:814–821 10.1242/dmm.007328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salas M, John R, Axena A, Barton S, Frank D, Fitzpatrick G, et al. Placental growth retardation due to loss of imprinting of phlda2. Mech Dev. 2004; 121:119–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tunster S, Tycko B, and John R. The Imprinted Phlda2 Gene Regulates Extraembryonic Energy Stores. Mol Cell Biol. 2010; 30(1):295–306 10.1128/MCB.00662-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews S, Wood M, Tunster S, Barton S, Surani A, John R. Cdkn1c (p57kip2) is the Major Regulator of Embryonic Growth Within its Imprinted Domain on Mouse Distal Chromosome 7. BMC Dev Biol. 2007; 7:53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Constancia M, Hemberger M, Hughes J, Wendy D, Ferguson-Smith A, Fundele R, et al. Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator of placental and fetal growth. Nature. 2002; 417: 945–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coan PM, Fowden AL, Constancia M, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ, Sibley CP. Disproportional effects of Igf2 knockout on placental morphology and diffusional exchange characteristics in the mouse. J Physiol. 2008; 586:5023–5032 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.157313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun F-L, Dean W, Kelsey G, Allen N, and Reik W. Transactivation of Igf2 in a mouse model of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nature. 1997; 389: 809–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charalambous M, Cowley M, Geoghegan F, Smith F, Radford E, Marlow B, et al. Maternally-inhertied Grb10 reduces placental size and efficiency. Dev Biol. 2010; 337: 1–8 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wylie AA, Pulford DJ, McVie-Wylie AJ, Waterland RA, Evans HK, Chen YT et al. Tissue-specific Inactivation of murine M6P/Igf2r . Am J Pathol. 2003; 162:321–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sekita Y, Wagatsuma H, Nakamura K, Ono R, Kagami M, Wakisaka N, et al. Role of retrotransposon-derived imprinted gene, Rtl1, in the feto-maternal interface of mouse placenta. Nat Genet. 2008; 40:243–248 10.1038/ng.2007.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lefebvre L, Viville S, Barton S, Ishino F, Keverne E, Surani A. Abnormal maternal behavior and growth retardation associated with loss of the imprinted gene Mest . Nat Genet. 1998; 20:163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ono R, Nakamura K, Inoue K, Naruse M, Usami T, Wakisaka-Saito N, et al. Deletion of Peg10, an imprinted gene acquired from a retrotransposon, causes early embryonic lethality. Nat Genet. 2006; 38:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li E, Bestor T, and Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992; 69:915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lei H, Oh S, Okano M, Juttermann R, Gross K et al. De novo DNA cytosine methyltransferase activities in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 1996; 122:3195–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Toppings M, Castro C, Mills P, Reinhart B, and Schatten G, Ahrens E, et al. Profound phenotypic variation among mice deficient in the maintenance of genomic imprints. Hum Reprod. 2008; 23:807–818 10.1093/humrep/den009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Himes KP, Koppes E, Chaillet JR. Generalized disruption of inherited genomic imprints leads to wide-ranging placental defects and dysregulated fetal growth. Dev Biol. 2013; 373: 72–82 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGraw S, Oakes C, Martel J, Cirio M, de Zeeuw P, Mark W, et al. Loss of DNMT1o disrupts imprinted X chromosome inactivation and accentuates placental defects in females. PLoS Genet. 2013; 9(11):e1003873 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Calvello M, Tabano S, Colapietro P, Maitz S, Pansa A, Augello C, et al. Quantitative DNA methylation analysis improves epigenotype-phenotype correlations in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Epigenetics. 2013; 8:1053–1060 10.4161/epi.25812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fuke T, Mizuno S, Nagai T, Hasegawa T, Horikawa R, Miyoshi Y, et al. Molecular and clinical studies in 138 Japanese patients with Silver-Russel Syndrome. PLoS One. 2013; 8(3):e60105 10.1371/journal.pone.0060105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Himes KP, Young A, Koppes E, Stolz D, Barak Y, Sadovsky Y, et al. Loss of inherited genomic imprints in mice leads to severe disruption in placental lipid metabolism. Placenta. 2015; 36:389–396 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oh-McGinnis R, Bogutz A, Lebebvre L. Partial loss of Ascl2 function affects all three layers of the mouse placenta and causes intrauterine growth restriction. Dev Biol. 2011; 351:277–286 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Green K, Lewis A, Dawson C, Dean W, Reinhart B, et al. A developmental window of opportunity for imprinted gene silencing mediated by DNA methylation and the Kcnq1ot1 noncoding RNA. Mamm Genome. 2007; 18:32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Arima T, Hata K, Tanaka S, Kusumi M, Li E, Kato K, et al. Loss of the maternal imprint in the Dnmt3Lmat-/- mice leads to a differentiation defect in the extraembryonic tissue. Dev Biol. 2006; 297:361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schulz R, Proudhon C, Bestor T, Woodfine K, Lin CS, Lin SP, et al. The parental non-equivalence of imprinting control regions during mammalian development and evolution. PLoS Genet. 2010; 6:(11)e1001214 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scott IC, Anson-Cartwright L, Riley P, Reda D, Cross JC. The Hand1 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor regulates trophoblast differentiation via multiple mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000; 30:530–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Simmons D, Cross JC. Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2005; 284:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hu D, Cross JC. Development and function of trophoblast giant cells in the rodent placenta. Int J Dev Biol. 2010; 54:341–354 10.1387/ijdb.082768dh [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fitzpatrick G, Soloway P, Higgins M. Regional loss of imprinting and growth deficiency in mice with a targeted deletion of KvDMD1. Nat Genet. 2002; 32:426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Choufani S, Shapiro J, Suisarjo M, Butcher D, Grafodatskaya D, Lou Y, et al. A novel approach identifies new differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with imprinted genes. Genome Res. 2011; 21:465–476 10.1101/gr.111922.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Court F, Tayama C, Romanelli V, Martin-Trujillo A, Iglesias-Platas I, Okamura K, et al. Genome-wide parent-of-origin DNA methylation analysis reveals the intracacies of human imprinting and suggests a germline methylation-independent mechanism of establishment. Genome Res. 2014; 24:554–569 10.1101/gr.164913.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Binned scatter plot showing individual wt and mt placenta across mid-gestation and the sample mean for the following imprinted gDMDs: (A) Grb10, (B) Plagl1, (C) Dlk1.A, (D) Dlk1.B, (E) Nespas.A, (F) Nespas.B, (G) Impact.A and (H) Impact.B. Brackets indicate significant differences between mutant gDMD methylation medians at different gestational ages. * (P<0.01) and **(P<0.001) denote significant differences of mutant median imprinted gDMD methylation compared to wild type, or between gestational ages of mutant sample population by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

Data displayed as binned scatter plots showing individual wt and mt placentas across mid-gestation and the sample mean for the following imprinted gDMDs: (A) Commd1, (B) Nnat, (C) and Nap1l5. No significant changes in gDMD methylation levels between mt cohorts at E12.5 and E15.5 were detected by the Rank-Sum test.

(PDF)

Data is shown as the log2 transformed ratio of mt:wt gDMD methylation. The heat map displays normally methylated gDMDs as dark boxes whereas loss of methylation is indicated by lighter shades. The upper and side dendrograms display linkage between imprinted gDMDs and DNMT1o-deficient samples respectively. Imprinted gDMDs are labeled across the bottom axis. DNMT1o-deficient samples are labeled down the right hand side by cohort litter (Letters A-D) and conceptus (Numbers 1–8).

(PDF)

Data is shown as the log2 transformed ratio of mt:wt gDMD methylation. The heat map displays normally methylated gDMDs as dark boxes whereas loss of methylation is indicated by lighter shades. The upper and side dendrograms display linkage between imprinted gDMDs and DNMT1o-deficient samples respectively. Imprinted gDMDs are labeled across the bottom axis. DNMT1o-deficient samples are labeled down the right hand side by cohort litter (Letters A-G) and conceptus (Numbers 1–8).

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume, and (C) the number of TGCs per slide of wt, mt-live and mt-dead placental cohorts are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume, and (C) the number of TGCs per slide of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female placental cohorts are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denotes significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt and mt cohorts are displayed as open and filled bars respectively. Data are displayed as mean + SEM. * (P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt and mt averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt, mt-live and mt-dead cohorts are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, (B) Wet fetal weight, and (C) Spongiotrophoblast and Labyrinth central volume of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female cohorts are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denotes significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placental weights and (B) Wet fetal weights of wt and mt cohorts are shown as open and filled bars respectively. Data are displayed as mean +SEM. ** (P<0.001) by the Rank-Sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight and (B) Fetal weight of wt, mt-live and mt-dead conceptuses are displayed as white, black and gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt, mt-live and mt-dead averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Wet placenta weight, and (B) Wet fetal weight, of wt-male, mt-male, wt-female and mt-female conceptuses are displayed as white, black, light-gray and dark-gray bars respectively. Data are plotted as mean + SEM. *(P<0.05) and **(P<0.005) denote significant differences between wt-male, wt-female, mt-male and mt-female averages by the Rank-sum test.

(PDF)

(A) Negative association between Nespas.A gDMD methylation and placental weight. (B) Negative association between Nespas.A gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (C) Negative association between Nespas.B gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (D) Negative association between H19 gDMD methylation and spongiotrophoblast volume. (E) Positive association between Peg10 gDMD methylation and labyrinth volume. (F) Negative association between Nnat gDMD methylation and labyrinth volume. R2 is unadjusted R-square value.

(PDF)

(A) Negative association between Kcnq1 gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (B) Negative association between Snrpn gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (C) Negative association between Plagl1 gDMD methylation and TGC counts. (D) Negative association between Nespas.B gDMD methylation and TGC counts. R2 is unadjusted R-square value.

(PDF)

Forward and Reverse sequence tags attached to each primer pair for EpiTYPER methylation analysis. Genomic coordinates of imprinted gDMDs from the most recent mouse genome build (GRCm38). Imprinted gDMD amplicons in bold were those used to calculate average imprinted gDMD methylation fraction in Fig 1A.

(PDF)

N = 24, df = 21, model P-value = 1.54x10-5.

(PDF)

Only significant (P<0.05) associations are shown. Regression coefficient is either the logit (log odds ratio) for logistic regression for fetal viability, or the linear regression coefficient (β) for all other variables.

(PDF)

Only associations with strong (P<0.075) are shown. The linear regression coefficient (β) is reported for both phenotypic variables.

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.