Abstract

Cytopaenias, especially anaemia, are common in the HIV-infected population. The causes of HIV related cytopaenias are multi-factorial and often overlapping. In addition, many of the drugs used in the management of HIV-positive individuals are myelosuppresive and can both cause and exacerbate anaemia. Even though blood and blood products are still the cornerstone in the management of severe cytopaenias, how HIV may affect blood utilisation is not well understood. The impact of HIV/AIDS on blood collections has been well documented. As the threat posed by HIV on the safety of the blood supply became clearer, South Africa introduced progressively more stringent donor selection criteria, based on the HIV risk profile of the donor cohort from which the blood collected. The implementation of new testing technology in 2008 which significantly improved the safety of the blood supply enabled the removal of what was perceived by many as a racially based donor risk model. However, this new technology had a significant and sustained impact on the cost of blood and blood products in South Africa.

In contrast, it would appear little is known of how HIV influences the utilisation of blood and blood products. Considering the high prevalence of HIV among hospitalised patients and the significant risk for anaemia among this group, there would be an expectation that the transfusion requirements of an HIV-infected patient would be higher than that of an HIV-negative patient. However, very little published data is available on this topic which emphasises the need for further large-scale studies to evaluate the impact of HIV/AIDS on the utilisation of blood and blood products and how the large-scale roll-out of ARV programs may in future play a role in determining the country’s blood needs.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Blood utilisation, Anaemia, Antiretroviral therapy, South Africa

1. HIV/AIDS: a changing epidemic

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has irrevocably changed the face of healthcare delivery and research. HIV is arguably the most researched disease and organism of all times, yet remains one of the leading causes of death in Africa. By the year 2000, less than twenty years after its identification, HIV/AIDS related deaths surpassed malaria as the leading cause of death in Africa [1]. On a global scale, it is estimated that by 2012 around 35 million people were living with HIV/AIDS, of whom 10% were children younger than 15 years of age [2]. The 2011 UNAIDS HIV/AIDS progress report [3] showed an estimated 15% decrease in incident (new) HIV infections; however, there was still an alarming 2.7 million (estimated) new infections during 2010 globally.

2. HIV/AIDS in South Africa

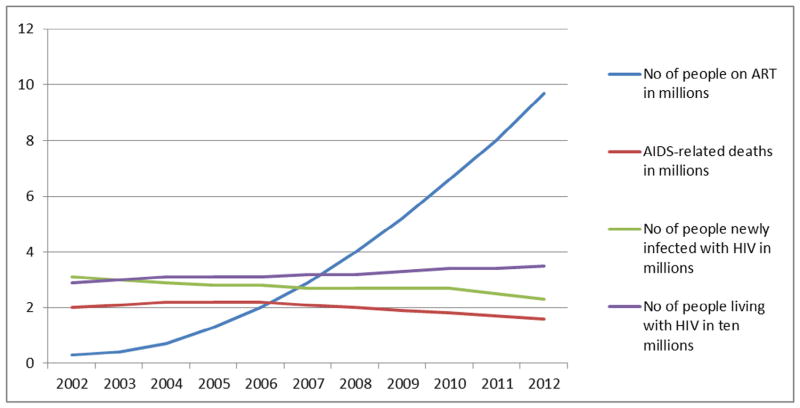

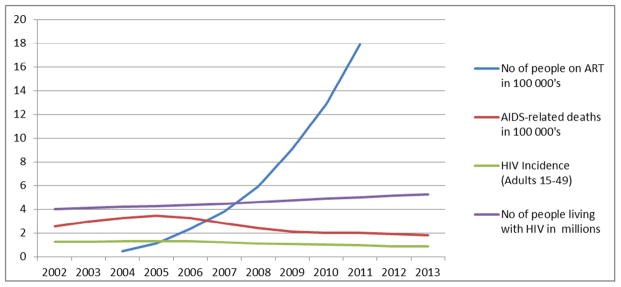

It is a well-established fact that the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic is the largest in the world, contributing approximately 17% of the total number of HIV infected persons globally, despite having only 0.7% of the world population [4–6]. The size of the epidemic in South Africa is greater than that of all of Asia combined, with an estimated 5.26 million people currently infected in South Africa [3,7]. In addition to the size of its epidemic, South Africa has not shown a similar significant downward trend in its HIV-related epidemiological data as seen in other countries or regions. With an annual incidence rate of around 0.85% [7], South Africa’s massive contribution to the extent of the pandemic is likely to continue for the foreseeable future (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Change in the global HIV epidemic, 2002 to 2012.

Fig. 2.

Change in the South African HIV epidemic, 2002 to 2013.

Adapted from Mid-year population estimates 2011: Global HIV/AIDS response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access. Progress Report 2011 and various STATSA reports [7,12–14].

In the book “HIV/AIDS in South Africa” [15], Dr Mark Colvin wrote: “There is a scarcity of data on the impact of HIV on health care services with most of it coming from small cross-sectional studies. Even the longitudinal data tends to be focused on specific wards and with no large-scale studies published; there are few data on the impact on health services more broadly”. This is especially true with regard to the impact of the epidemic on blood utilisation. However, the massive influx of donor funding after 2004, reaching values in excess of US$10 billion in 2007 [16], has enabled the funding of care of millions of people living with HIV/AIDS. Despite this, more than 50% of people eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) still do not have access to care [16]. The influx of donor funding has heralded a change from an emergency response to a more long-term sustained effort towards the management of HIV/AIDS [16–18]. Despite the significant increase in the funding of both HIV/AIDS research and care, it remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the full impact of this disease on a macro- and micro-economic level, including health care utilisation and redistribution, remains unclear.

On a micro-economic level, it has long been established that both the direct and indirect costs of care for HIV-positive patients significantly exceeds those of HIV-negative patients. As far back as 1988, Hassig et al. demonstrated a significantly higher cost of care, both direct and indirect, for HIV-positive patients compared to HIV-negative patients in Kinshasa, in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo [19]. These findings were echoed by similar studies from the United States [20,21]. It has been noted that the displacement of HIV-negative patients by their HIV-positive counterparts may have, in fact, affected the mortality rate of HIV-negative patients, probably due to the delayed admission of the HIV-negative patients, when conditions which generally would have been infinitely treatable, have deteriorated to the point where mortality become imminent [19].

In addition to incurring higher cost of care than HIV-negative patients, HIV-positive patients have been shown to dominate bed-occupancy in those countries with high prevalence epidemics. The shift from an HIV infection epidemic in South Africa to that of an AIDS care one has been well documented. In 2001, Colvin et al. showed that in a tertiary referral hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, at least 54% of all admissions to the adult medical wards were HIV positive and of those, 84% had AIDS [22]. Similarly, Pillay et al. found that 62% of paediatric admissions to the King Edward Hospital were HIV positive [23]. Several epidemiological studies during the late 1990s indicated a high prevalence of HIV among hospital inpatients in Sub-Saharan Africa as well as in South Africa, even among surgical and psychiatric patients [24–28]. HIV-positive patients were shown to have extended lengths of stay compared to their HIV-negative counterparts and was more likely to have had repeated admissions [26]. These findings were replicated in paediatric wards, although usually limited to infants, a finding probably related to the high mortality rate among HIV-positive infants [23,29]. Of particular note has been the consistent finding that HIV-positive inpatients tended to be younger, have a greater mortality rate and higher rates of tuberculosis than inpatients admitted for non-HIV-related conditions [15,22,23]. Some later studies performed among surgical patients during the early half of the first decade of this century showed HIV prevalence rates of between 32% and 39% [30,31]. Even though we have not been able to find more recent reports on HIV/AIDS related bed occupancy, there has been nothing to suggest that these trends would have changed in any significant manner.

From the above discussion it is clear that there is a direct relationship between HIV/AIDS and health resource utilisation in general and hospitalisation in particular, but is has not been established whether there may also be such a relationship between HIV/AIDS and the utilisation of blood and blood products. Blood and blood products are still the conventional treatment of severe cytopaenias and so one has to review the role of cytopaenias in HIV to assess how HIV may affect blood utilisation.

3. Anaemia in HIV

Cytopaenias are common in the HIV-infected population [32–34]. Anaemia is the most common haematological abnormality found in HIV. It may occur at any stage of the disease and its prevalence and severity increases as the disease progresses [33,34]. It is estimated that 63–95% of HIV infected individuals will develop anaemia during the course of their disease [33–35]. It has also been shown to be an independent risk factor for mortality and that reversal of anaemia improves mortality rates, even after controlling for confounding factors such as CD4 count [36,37]. Anaemia in HIV, as in other chronic diseases, is associated with reduced quality of life (QoL) and its resolution with significant improvement in QoL [38,39]. In particular, patients reported improvement in physical functioning and in energy/fatigue scales, factors known to be affected by HIV status, independent of the presence of anaemia. In an open-label study in 1994, Revicki et al. demonstrated significant changes in energy levels and concomitant increases in health perceptions and satisfaction with health in patients with AIDS who responded to recombinant human erythropoietin (r-HuEPO) for the treatment of their anaemia [40]. The beneficial effects of resolution of anaemia are not limited to those with AIDS, but extend to patients with earlier stages of HIV disease [41]. In contrast, HIV-positive anaemic patients, not only demonstrated poorer QOL assessments, but were also noted to have higher health resource utilisation scores [42].

The early diagnosis and prompt management of anaemia in the setting of HIV is not only important to improve clinical outcomes and QoL, but can play an important role to reduce health resource utilisation. However, to do this, requires a good understanding of the pathophysiology of anaemia in HIV. The causes of anaemia in HIV are multifactorial, often overlapping and occurring simultaneously in the same patient (Table 1). It may be the result of either the direct or indirect effects of the HIV infection and can affect both the production as well as the destruction/survival of red blood cells. HIV may affect erythropoiesis directly through infection of red cell precursors and bone marrow stromal cells, as well as through the release of cytokines. These factors contribute to the development of anaemia of chronic disease (ACD) and are likely responsible for the majority of cases of anaemia in HIV-positive patients, who would usually present with a moderate, normochromic, normocytic anaemia [34]. ACD is associated with inappropriately low erythropoietin levels (compared to the degree of anaemia), a suppressed reticulocyte response and defective iron metabolism.

Table 1.

Anaemia in HIV [43].

| Decreased production | Increased loss and/or destruction |

|---|---|

Drugs

Infections

Neoplasia

Miscellaneous

|

Haemolysis

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Hypersplenism

Idiopathic |

Anaemia may also be the result of the indirect effects of HIV infection. Common among these are the nutritional deficiencies as a result of the anorexia, malabsorption and metabolic disorders associated with HIV. With disease progression, opportunistic infections, neoplasms, infiltrative and infective bone marrow conditions and drug interactions increase in importance as the causes of anaemia in HIV. Among the opportunistic infections which can lead to profound anaemia is parvovirus B19 infection, which infects and destroys erythrocyte precursors resulting in severe anaemia, often requiring multiple blood transfusions.

Many of the drugs used in the management of HIV-positive individuals are myelosuppresive and can both cause and exacerbate anaemia. Most notable is zidovudine; however, a review of patients receiving zidovudine in a resource-limited setting in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (previously Zaire) suggested that the presence of baseline anaemia should not preclude the use of zidovudine in resource limited settings as most patients experience improvement of their anaemia in response to the initiation of a zidovudine containing ART regime [44]. This echoed findings by Sullivan et al. which showed that zidovudine use was associated with a higher risk of drug-induced anaemia, but was found to be protective against other forms of anaemia [33]. In addition, many of the drugs used in prophylaxis against or treatment of opportunistic infections may cause or aggravate anaemia [32,45]. These include, amongst other, trimethoprim, sulfonamides and several anti-tuberculosis drugs.

The above mentioned conditions mostly affect red cell production, but HIV may also affect red cell survival and destruction. Despite up to a third of HIV-infected patients having a positive direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test (DAT), clinically significant autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA) is uncommon [34]. However, there is a real risk of underreporting of the condition due to the difficulty in confirming the diagnosis in the presence of a lack of reticulocytosis, a common finding in HIV-positive patients, i.e. patients may have a low level of AIHA, but due to the fact that, for various reasons associated with their HIV infection, they are unable to mount a reticulocytosis, confirmation of AIHA becomes difficult [46]. In 2008, Olayemi et al. screened 98 consecutive HIV-positive patients presenting at their outpatient clinic for routine follow up for AIHA. For the purpose of this study, AIHA was defined as a packed cell volume of less than 30%, a positive DAT and a reticulocyte count of greater than 2.5% [47]. They noted an 11% DAT positivity among their patients with a total of 3% of all of the patients meeting their criteria for AIHA. Anaemia was present in 36.7% of all patients (i.e. Hct <30%), implying that of those who were anaemic, just more than 8% met the criteria for AIHA, suggesting that the condition may not be as rare as what is generally believed. Another cause of HIV-associated red cell destruction is HIV-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). HIV-associated TTP is significantly more common than TTP associated with other conditions [34,48,49]. The association between HIV and TTP was noted during the late 1980s [50,51] and in 2004, Becker et al. noted a 0.3% prevalence of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) among a group of HIV-positive individuals in the USA and an unadjusted incidence of 0.009 per 100 person-years for TTP [52]. TTP were more common in those with lower CD4 counts and higher viral loads [52]. HIV-associated TTP is the most frequently encountered TMA in South Africa and is likely a reflection of the extent of the epidemic as well as the, until recently, poor access to ART [48,49,53,54]. It has been postulated that HIV-associated TTP may be triggered through the inflammatory process [55], which would explain the decreasing incidence after initiation of ART, which also reduces the inflammatory state. In the presence of thrombocytopenia and red cell fragments on the peripheral blood smear, TTP should always be considered as part of the differential diagnosis. Considering then, the relative frequency of both AIHA and TTP in the HIV-positive population, it is essential that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion for these conditions and actively investigate for their presence wherever doubts exist regarding the aetiology of anaemia in HIV.

Early and appropriate diagnosis and investigation of anaemia in HIV are cardinal points in the management of any person living with HIV. The multifactorial nature of anaemia in HIV can make the investigation thereof a complex and costly exercise, but there are certain basic laboratory investigations which will assist in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Although various publications define anaemia at different haemoglobin (Hb) levels [56–58], new full blood count reference ranges were published for South Africa in 2009, which suggest the lower limit for Hb in males to be 13.4 g/dL and 11.6 g/dL in females [59]. This is in line with the 1968 WHO report [60] which suggested a patient would be anaemic if the Hb was less than 13 g/dL in adult men and less than 12 g/dL in adult, non-pregnant females.

Determining an accurate Hb level as part of a full blood count (FBC) is therefore the first step in diagnosing and investigating anaemia. Determining the bone marrow response to the anaemia may assist in deciding whether the anaemia is due to a production deficit or due to peripheral loss or destruction and for this a reticulocyte count and reticulocyte production index is helpful. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) assists in further narrowing the differential diagnosis, with the most common causes of a low MCV being iron deficiency secondary to chronic blood loss followed by ACD. In the setting of HIV, a normal MCV is most commonly associated with ACD and a high MCV with nutritional deficiencies and various drugs. Serum bilirubin levels, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and a peripheral blood smear are valuable in assessing cases of suspected peripheral loss or destruction, where AIHA or TTP is suspected. These few simple investigations will assist in delineating the underlying cause of the anaemia in most patients and should ideally be performed prior to the initiation of any therapy, including blood transfusions.

4. The impact of antiretroviral therapy

A plethora of articles were published in the 1990s and early parts of the first decade of this millennium on anaemia in HIV, with much of it predating the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Today, it is well established that appropriate ART taken regularly, provides long-lasting viral suppression with significant reduction in morbidity and mortality, even though it does not afford a cure and requires lifelong treatment [61]. It has, essentially, converted what was a uniformly fatal disease, to a chronic, manageable condition for most patients, albeit with a somewhat compromised life expectancy. Access to ART increased significantly over time, with an estimated 47% of patients in low- and middle-income countries who qualify for treatment having access by the end of 2010. In South Africa, an estimated 52–55% of eligible patients had access to ART, meaning that there was still in the region of 1.2 million people eligible for treatment who do not have access [3,12]. It is further estimated that having access to ART resulted in 460 000 (or 30%) fewer South Africans dying from AIDS related causes in 2010 than in 2004 [3] and that compared to the 1980s the current life expectancy of a newly infected 20-year old person with access to guideline-recommended therapy at CD4 counts greater than 200/μL is 50.4 years [62]. Johnson (2012) [12] demonstrated in her recently published article, Access to Antiretroviral Treatment in South Africa, 2004–2011, that the previously unmet need for ART in South Africa has been reduced by 30% between 2007 and 2011. This was mainly due to the implementation of a comprehensive care, management and treatment program by the South African Department of Health in the latter part of 2003. It was estimated that the adult ART coverage was around 80% by mid-2011, but with major differences between males and females, with more females accessing care than males. This is significantly higher than the 55% coverage reported in the 2011WHO report and may reflect major uptake during 2010 and the first half of 2011, confirming a major and continued uptake of therapy across South Africa.

Access to ART within the South African context is likely to have a significant impact on various aspects of health care and health care utilisation as the introduction of ART is associated with fewer hospital admissions and a trend towards shorter lengths of stay, with an overall decrease in health care utilisation once patients have been stabilised on their treatment [63]. It has been clearly demonstrated to reduce health care costs, especially if started early [64–66], and would in all likelihood be cost-effective, even over the associated extended life expectancy of those HIV-infected individuals taking appropriate ART [67]. What is less clear is the impact of ART on anaemia and the need for blood transfusions in HIV. Several studies have reviewed the effect of ART on the prevalence of anaemia, with some contradicting results. A recently published study, involving 230 patients from Ethiopia, showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of anaemia after the initiation of ART, but notes that the decrease was not a consistent finding among all those who were commenced on ART [68]. These findings echoed those of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, which showed that ART was associated with resolution of anaemia, even when used for as short as 6 months [69]. This is in contrast to a multi-centre cross-sectional study in the USA in 2007, which showed very little difference in the prevalence of anaemia between those who were receiving ART and those who were not [70]. The fact that this study relied on results from a single visit may have resulted in the confounding findings of the data and requires further investigation. It does, however, echo the findings of Murphy et al. in 2001 [71], who found that red blood cell (RBC) transfusion decreased during the course of the Viral Activation Transfusion Study, but that, after adjusting for calendar period and time on the study, the decrease could not be conclusively attributed to the use of ART. From these studies, it is clear that despite the fact that one would expect the prevalence of anaemia and thus the need for transfusion to decrease with access to appropriate ART, this has not yet clearly been established in the literature, with several ambivalent reports being published.

5. HIV/AIDS and blood collection

The HIV pandemic irrevocably changed blood collection practices both internationally as well as locally. The emergence and recognition of HIV as a transfusion-transmissible infection, initiated dramatic changes in the collection and testing of donor blood. In many countries, it is this realisation of the HIV risk in the blood pool, which resulted in stringent government regulation of blood collection and blood collection centres [72–75]. Similarly, within the South African Blood Services (SANBS) the HIV/AIDS pandemic has had a huge impact on donor recruitment and blood collection [76]. After the initial realisation of the threat that HIV holds to the country’s blood supply, progressively more stringent donor selection criteria were introduced. New testing technologies were introduced, accompanied by the development of a risk model for the release of blood products based on the HIV risk profile of the donor cohort from which it was collected. Many perceived this to be racial profiling of blood donors and in consultation with the National Department of Health; this risk model was repealed with the introduction of individual donation nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) to screen for HIV as well as hepatitis B and C [76]. Even today, the very high background prevalence of HIV among the population from which blood donors are recruited, places significant strain on the various blood transfusion services in South Africa.

6. HIV/AIDS and blood transfusion

Whereas the impact of HIV on the procurement of blood has been well documented, the specific impact of the epidemic on the utilisation of blood and blood products has not been fully examined, nor is it clear whether there would be a higher prevalence of HIV among patients who require blood transfusions. Considering the high prevalence of HIV among hospitalised patients and the significant risk for anaemia among this group, there would be an expectation that the transfusion requirements of an HIV-infected patient would be higher than that of an HIV-negative patient. We were only able to locate one small study performed at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, that investigated the impact of HIV on the utilisation of blood products. In reviewing the South African Haemovigilance reports for the period 2007 to 2010, we note a 30% increase in the utilisation of red cell concentrate (RCC) products over this period [77,78]. It is not clear what drove this increase in utilisation but, what is notable is the analysis in the 2007 report which indicated that most of the blood issued in the inland provinces of South Africa were issued to medical patients [77,78]. For a country renowned for interpersonal violence and trauma, surgical usage was only about half that of the medical usage. This significant increase in RCC may be due to various reasons, but is likely to include HIV/AIDS.

The Groote Schuur Hospital blood utilisation study aimed to assess HIV as a key driver of the increase in blood and blood products that was identified through the increase in expenditure on blood and blood products in the medical wards of this hospital [79]. They performed a prospective audit to evaluate the impact of HIV/AIDS on blood utilisation. A small cohort of 67 patients who received 590 units of blood and blood products were identified for inclusion in the study by self-reporting of the prescribing doctors or by the nursing staff who commenced the transfusions. The investigators administered a standardised, structured questionnaire, recording standard demographic data as well as baseline haematological indices, HIV status, CD4 counts and ART regimen (where applicable), reason for admission, co-morbidities, indication for transfusion, number of units transfused and the presence of any transfusion reactions. Of the 67 patients, 61% were HIV-positive and of these, 41% were on ART. Only four of the 17 patients on ART were on an AZT containing regime. Anaemia was the most common indication for transfusion in both the HIV-negative as well as positive groups. However, HIV positivity, especially those not on ART, was associated with significantly more units of RCC being transfused. Of the 154 RCC transfused, 40 (26%) were issued to HIV-negative patients and 80 (52%) were issued to HIV-positive patients not on ART. Furthermore, of the 397 units of fresh frozen plasma issued, 371 (93%) were issued to HIV-positive patients not on ART, likely reflecting several TTP cases requiring repeated large volume plasma transfusions.

Despite the limited sample size, the voluntary participation of doctors and reliance on self-reporting, these findings are significant and would certainly suggest that in this population, at least, HIV/AIDS is a significant driver of utilisation of blood and blood products and that initiation of ART likely affords protection against conditions requiring the transfusion of blood and blood products, such as chronic anaemia and TTP [79].

7. Conclusion

These findings would support the need for further research involving various disciplines and a larger sample size to fully establish the impact of HIV on blood transfusion, in particular, what proportion of blood is transfused to HIV positive patients and whether those who are HIV positive require more blood transfusions than those who are HIV negative. Although there is some suggestion that doctors have been influenced in their prescribing habits by the risk of HIV transmission through blood transfusions, resulting in transfusion at lower Hb levels than before [80], it is unclear whether the prescribing habits of physicians are influenced by a patient’s HIV status, i.e. how rigorously is the cause of the underlying anaemia investigated, is proper informed consent taken and is this application of good transfusion practice [81] dependent on the patient’s HIV status.

In an era of ever increasing medico-legal litigation, both in private and public practice, being able to assess current practice and institute corrective action for areas failing to meet minimum ethical and legal standards relating to transfusion medicine, may contribute to improving the overall adherence to legal and ethical standards in healthcare practice.

References

- 1.Barnett T, Whiteside A, Desmond C. The social and economic impact of HIV/AIDS in poor countries: a review of studies and lessons. Prog Dev Stud. 2001;1:151–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) UNAIDS World AIDS day report 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [accessed 23.11.13]. < http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/JC2434_WorldAIDSday_results_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), (WHO) WHO. Fund UNCs. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access: progress report 2011. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. [accessed 20.04.12]. < http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/hiv_full_report_2011.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), (WHO) WHO. AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007. [accessed 20.04.12]. < http://data.unaids.org/pub/epislides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 5.South African Department of Health. South Africa 2007. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2008. [accessed 20.04.12]. The national HIV and syphilis prevalence survey. < http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/epidemiology/countryestimationreports/20080904_southafrica_anc_2008_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Organisation WH. HIV/AIDS epidemiological surveillance report for the WHO African Region: 2007 update. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates. [accessed 23.11.13];Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2013 July 2012. 2013 < http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022013.pdf>.

- 8.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Health Organisation (WHO) AIDS Epidemic Update: November 2009. UNAIDS; 2009. [accessed 20.08.11]. < http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) AIDS by the numbers. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [accessed 23.11.13]. UNAIDS 2013. < http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2013/JC2571_AIDS_by_the_numbers_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Health Organisation (WHO) UNAIDS annual report 2008: towards universal access. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2012. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. [accessed 23.11.13]. < http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/jc2434_worldaidsday_results_en.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson LF. Access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa, 2004–2011. [accessed 28.04.12];South Afr J HIV Med. 2012 13:22–7. < http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/sajhivmed/article/view/805>. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2011. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2011. < http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022011.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2011. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2012. [accessed 23.11.13]. Jul, < http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022011.pdf>. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colvin M. Impact of AIDS – the health care burden. In: Abdool Karim S, Abdool Karim Q, editors. HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.PEPFAR. Celebrating life: the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS relief 2009 annual report to Congress on PEPFAR. Washington: PEPFAR; 2009. [accessed 10.05.12]. < http://www.pepfar.gov/press/fifth_annual_report/>. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson HJ, Bertozzi S, Piot P. Redesigning the AIDS response for long-term impact. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:846–52. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.087114. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=22084531&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piot P. AIDS: from crisis management to sustained strategic response. Lancet. 2006;368:526–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69161-7. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=16890840&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassig SE, Perriëns J, Baende E, et al. An analysis of the economic impact of HIV infection among patients at Mama Yemo Hospital, Kinshasa, Zaire. AIDS. 1990;4:883–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199009000-00009. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=2252561&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scitovsky AA, Cline M, Lee PR. Medical care costs of patients with AIDS in San Francisco. JAMA. 1986;256:3103–6. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=3783846&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seage GR, 3rd, Landers S, Barry A, Groopman J, Lamb GA, Epstein AM. Medical care costs of AIDS in Massachusetts. JAMA. 1986;256:3107–9. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=3491224&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colvin M, Dawood S, Kleinschmidt I, Mullick S, Lallo U. Prevalence of HIV and HIV-related diseases in the adult medical wards of a tertiary hospital in Durban, South Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:386–9. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923336. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=11368820&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pillay K, Colvin M, Williams R, Coovadia HM. Impact of HIV-1 infection in South Africa. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:50–1. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.1.50. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=11420200&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floyd K, Reid RA, Wilkinson D, Gilks CF. Admission trends in a rural South African hospital during the early years of the HIV epidemic. JAMA. 1999;282:1087–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1087. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=10493210&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins PY, Berkman A, Mestry K, Pillai A. HIV prevalence among men and women admitted to a South African public psychiatric hospital. AIDS Care. 2009;21:863–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120802626188. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=20024743&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buvé A. AIDS and hospital bed occupancy: an overview. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:136–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-235.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9472298&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilks CF, Floyd K, Otieno LS, Adam AM, Bhatt SM, Warrell DA. Some effects of the rising case load of adult HIV-related disease on a hospital in Nairobi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:234–40. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199807010-00006. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9665500&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bateman C. Can KwaZulu-Natal hospitals cope with the HIV AIDS human tide? S Afr Med J. 2001;91:364–8. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=11455795&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers TM, Pettifor JM, Gray GE, Crewe-Brown H, Galpin JS. Pediatric admissions with human immunodeficiency virus infection at a regional hospital in Soweto, South Africa. J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46:224–30. doi: 10.1093/tropej/46.4.224. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=10996984&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinson NA, Omar T, Gray GE, et al. High rates of HIV in surgical patients in Soweto, South Africa: impact on resource utilisation and recommendations for HIV testing. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.04.002. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=16814822&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cacala SR, Mafana E, Thomson SR, Smith A. Prevalence of HIV status and CD4 counts in a surgical cohort: their relationship to clinical outcome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006:46–51. doi: 10.1308/003588406X83050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans RH, Scadden DT. Haematological aspects of HIV infection. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13:215–30. doi: 10.1053/beha.1999.0069. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=10942622&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan PS, Hanson DL, Chu SY, Jones JL, Ward JW. Epidemiology of anemia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons: results from the multistate adult and adolescent spectrum of HIV disease surveillance project. Blood. 1998;91:301–8. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9414298&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coyle TE. Hematologic complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:449–70. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70526-5. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9093237&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bain BJ. The haematological features of HIV infection. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2943111.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9359495&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan P. Associations of anemia, treatments for anemia, and survival in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(Suppl 2):S138–42. doi: 10.1086/340203. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=12001035&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chaisson RE. Anemia and survival in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:29–33. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00004. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9732065&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimel M, Leidy NK, Mannix S, Dixon J. Does epoetin alfa improve health-related quality of life in chronically ill patients with anemia? Summary of trials of cancer, HIV/AIDS, and chronic kidney disease. Value Health. 2008;11:57–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00215.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=18237361&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volberding P. The impact of anemia on quality of life in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(Suppl 2):S110–4. doi: 10.1086/340198. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=12001031&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revicki DA, Brown RE, Henry DH, McNeill MV, Rios A, Watson T. Recombinant human erythropoietin and health-related quality of life of AIDS patients with anemia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:474–84. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=8158542&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrams DI, Steinhart C, Frascino R. Epoetin alfa therapy for anaemia in HIV-infected patients: impact on quality of life. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:659–65. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915020. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=11057937&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolge SC, Mody S, Ambegaonkar BM, McDonnell DD, Zilberberg MD. The impact of anemia on quality of life and healthcare resource utilization in patients with HIV/AIDS receiving antiretroviral therapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:803–10. doi: 10.1185/030079907x178775. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=17407637&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van den Berg K, van Hasselt J, Bloch E, et al. A review of the use of blood and blood products in HIV-infected patients. South Afr J HIV Med. 2012;13:87–103. doi: 10.4102/sajhivmed.v13i2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiragga AN, Castelnuovo B, Nakanjako D, Manabe YC. Baseline severe anaemia should not preclude use of zidovudine in antiretroviral-eligible patients in resource-limited settings. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:42. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-42. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=21047391&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volberding PA, Levine AM, Dieterich D, Mildvan D, Mitsuyasu R, Saag M. Anemia in HIV infection: clinical impact and evidence-based management strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1454–63. doi: 10.1086/383031. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=15156485&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Telen MJ, Roberts KB, Bartlett JA. HIV-associated autoimmune hemolytic anemia: report of a case and review of the literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:933–7. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=2204697&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olayemi E, Awodu OA, Bazuaye GN. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in HIV-infected patients: a hospital based study. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7:72–6. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55677. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=19143163&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunther K, Garizio D, Dhlamini B. The pathogenesis of HIV-related thrombotic thrombocytopaemic purpura – is it different? ISBT Sci Ser. 2006;1:246–50. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novitzky N, Thomson J, Abrahams L, du Toit C, McDonald A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with retroviral infection is highly responsive to plasma infusion therapy. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:373–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05325.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=15667540&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson CE, Damon LE, Ries CA, Linker CA. Thrombotic microangiopathies in the 1980s: clinical features, response to treatment, and the impact of the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic. Blood. 1992;80:1890–5. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=1391952&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hymes KB, Karpatkin S. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and thrombotic microangiopathy. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:117–25. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=9109213&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker S, Fusco G, Fusco J, et al. HIV-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(Suppl 5):S267–75. doi: 10.1086/422363. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=15494898&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gunther K, Garizio D, Nesara P. ADAMTS13 activity and the presence of acquired inhibitors in human immunodeficiency virus-related thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion. 2007;47:1710–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01346.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=17725738&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Visagie GJ, Louw VJ. Myocardial injury in HIV-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) Transfus Med. 2010;20:258–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.01006.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=20409074&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meiring M, Webb M, Goedhals D, Louw V. HIV-associated Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura – what we know so far. Eur Oncol Haematol. 2012;8:89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald AB, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 13. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heyns A, Badenhorst PN. Anemie. In: Heyns A, Badenhorst PN, editors. Bloedsiektes. Kaapstad: Academica; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bain BJ. The blood count and film. In: Bain BJ, editor. Haematology: a core curriculum. Singapore: Imperial College Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lawrie D, Coetzee LM, Becker P, Mahlangu J, Stevens W, Glencross DK. Local reference ranges for full blood count and CD4 lymphocyte count testing. S Afr Med J. 2009;99:243–8. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=19588777&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nutritional anaemias. . Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1968;405:5–37. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=4975372&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon V, Ho DD, Abdool Karim Q. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Lancet. 2006;368:489–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69157-5. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=16890836&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372:293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=18657708&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harling G, Orrell C, Wood R. Healthcare utilization of patients accessing an African national treatment program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:80. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-80. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=17555564&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harling G, Wood R. The evolving cost of HIV in South Africa: changes in health care cost with duration on antiretroviral therapy for public sector patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:348–54. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180691115. < http://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2007/07010/The_Evolving_Cost_of_HIV_in_South_Africa__Changes.15.aspx>; 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180691115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krentz HB, Gill MJ. The direct medical costs of late presentation (<350/mm) of HIV infection over a 15-year period. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:757135. doi: 10.1155/2012/757135. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=21904673&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krentz HB, Gill J. Despite CD4 cell count rebound the higher initial costs of medical care for HIV-infected patients persist 5 years after presentation with CD4 cell counts less than 350 μl. AIDS. 2010;24:2750–3. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f9e1d. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=20852403&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johansson LM. Fiscal implications of AIDS in South Africa. Eur Econ Rev. 2007:1614–40. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adane A, Desta K, Bezabih A, Gashaye A, Kassa D. HIV-associated anaemia before and after initiation of antiretroviral therapy at Art Centre of Minilik II Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2012;50:13–21. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=22519158&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berhane K, Karim R, Cohen MH, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on anemia and relationship between anemia and survival in a large cohort of HIV-infected women: women’s interagency HIV study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1245–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134759.01684.27. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=15385731&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mildvan D, Creagh T, Leitz G. Prevalence of anemia and correlation with biomarkers and specific antiretroviral regimens in 9690 human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patients: findings of the Anemia Prevalence Study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:343–55. doi: 10.1185/030079906X162683. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=17288689&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy EL, Collier AC, Kalish LA, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy decreases mortality and morbidity in patients with advanced HIV disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:17–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00005. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=11434728&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Derrick JB. AIDS and the safety and adequacy of the Canadian blood supply. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1986;33:117–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03010818. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=3516333&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barnes DM. Keeping the AIDS virus out of blood supply. Science. 1986;233:514–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3460177. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=3460177&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samuels ME, Mann J, Koop CE. Containing the spread of HIV infection: a world health priority. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:221–3. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=3131810&site=ehost-live>. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aymard JP, Janot C, Contal P, Linel C, Monange G, Streiff F. Epidemiologic study of HIV serology in blood donors from 5 departments in northeastern France (1985–1989) Rev Fr Transfus Hemobiol. 1989;32:421–9. doi: 10.1016/s1140-4639(89)80009-7. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=2629757&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vermeulen M, Lelie N, Sykes W, et al. Impact of individual-donation nucleic acid testing on risk of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus transmission by blood transfusion in South Africa. Transfusion. 2009;49:1115–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02110.x. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=19309474&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.South African National Blood Service. Haemovigilance Report 2007. Johannesburg: South African National Blood Service; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 78.South African National Blood Service. Haemovigilance Report 2010. Johannesburg: South African National Blood Service; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ntusi NBA, Sonderup MW. HIV/AIDS affects blood and blood product use at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:463–6. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=21920098&site=ehost-live>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ravry ME, Paz HL. The impact of HIV testing on blood utilization in the intensive care unit in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:933–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01712335. < http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=8636526&site=ehost-live>. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Medical Directors of the South African Blood Transfusion Services. Clinical guidelines for the use of blood products in South Africa. 4. 2008. [Google Scholar]