Abstract

Background

Because as many as 46% of implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) patients experience clinical symptoms of shock anxiety, this randomized controlled study evaluated the efficacy of adapted yoga (vs. usual care) in reducing clinical psychosocial risks shown to impact morbidity and mortality in ICD recipients.

Methods

Forty-six participants were randomized to a control group or an 8-week adapted yoga group that followed a standardized protocol with weekly classes and home practice. Medical and psychosocial data were collected at baseline and follow-up, then compared and analyzed.

Results

Total shock anxiety decreased for the yoga group and increased for the control group, t(4.43, 36), p < 0.0001, with significant differences between these changes. Similarly, consequential anxiety decreased for the yoga group but increased for the control group t(2.86,36) p = 0.007. Compared to the control, the yoga group had greater overall self-compassion, t(–2.84,37), p = 0.007, and greater mindfulness, t(–2.10,37) p = 0.04, at the end of the study. Exploratory analyses utilizing a linear model (R2 = .98) ofobserved device-treated ventricular (DTV) events revealed that the expected number of DTV events in the yoga group was significantly lower than in the control group (p<.0001). Compared to the control, the yoga group had a 32% lower risk of experiencing device-related firings at end of follow-up.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated psychosocial benefits from a program of adapted yoga (vs. usual care) for ICD recipients. This data supports continued research to better understand the role of complementary medicine to address ICD-specific stress in cardiac outcomes.

Keywords: implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), randomized clinical trials, psychosocial risk, yoga, electrophysiology, quality of life

Introduction

Clear and convincing clinical evidence has established that living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) saves patients’ lives. In a 1999 landmark trial comparing the ICD to anti-arrhythmic drugs, the “ICD remains superior… in prolonging survival after life-threatening arrhythmia.”(1 p.1552) Concomitantly, psychosocial research on the ICD has shown that living with the device as a treatment for life-threatening arrhythmias can lead to further/increased anxiety, isolation, hostility, and depression. (2;3) The typical ICD recipient must overcome both the stress of life-threatening arrhythmias and the challenge of adjusting to the device, with 13% to 46% of patients experiencing anxiety symptoms and 24% to 46% of patients experiencing depressive symptoms. (4–7)

Clinical trials have demonstrated that psychological stress can have deleterious effects on the heart. Psychological stress has been shown to be a risk factor following myocardial infarction for ischemic complications, re-infarction, mortality, and in-hospital complications. Psychological stress adversely affects cardiac risk-factors and disease states, including the equilibrium of the autonomic nervous system and vagal control, which leads to increased incidence of significant ventricular tachyarrhythmia.(8; 9) Aberrations in autonomic cardiovascular regulation, such as impaired baroreflex response and decreased heart rate variability, also have been shown to be independent risk factors for sudden cardiac death.(9–11) Further, distressing emotional states, which can increase cardiac repolarization instability, precipitate life threatening ventricular arrhythmias in ICD patients.(8; 12) While the specific mechanisms of how psychological stress adversely affects the heart are not clearly known, “[p]ossible causes include heightened activation of the sympathetic nervous system, diminished parasympathic activity, alternations in coagulation and fibrinolysis, and reduced compliance with treatment programs.” (9 p.1919; 11)

Clinical trials have also shown yoga to be effective in addressing both psychological and physical components that are present in illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases.(13–16)These include cardiovagal function, sympathetic activation, oxidative stress, coagulation profiles, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.(13) Research using yogic breathing techniques in patients with arrhythmias has shown significant reduction in the indices of ventricular repolarization dispersion.(17) Participation in yoga may be particularly beneficial for ICD patients in addressing the psychological and physical rigors of living with cardiac disease and an ICD. Despite a seemingly good fit between patient symptomatology and the mind-body techniques of yoga, no published studies that evaluated yoga as treatment for psychosocial distress in ICD recipients were found in the biomedical literature.

Methods

Overview

This randomized controlled study examines the effects of a yoga intervention (gentle adapted yoga vs. standard medical care) on shock anxiety, ICD patient acceptance, and cardiac outcomes. Participants were ICD recipients, eighteen years or older, who received their device at least six weeks prior to the start of the intervention. Participants were randomized into intervention and control groups, with the intervention group following a specially designed cardiac yoga program and the control group following a modified program of standard care. This protocol sought to examine the effects of yoga on decreasing various stress- and anxiety-related measures and in reducing the likelihood of future device firings in participants. Psychosocial effects of the intervention and control protocols were measured at follow-up and compared with baseline values. The impact of the relationship between baseline risk factors and subsequent device episodes was also investigated. Data was examined through statistical analysis for significance or predictive clinical relevance.

Study Design

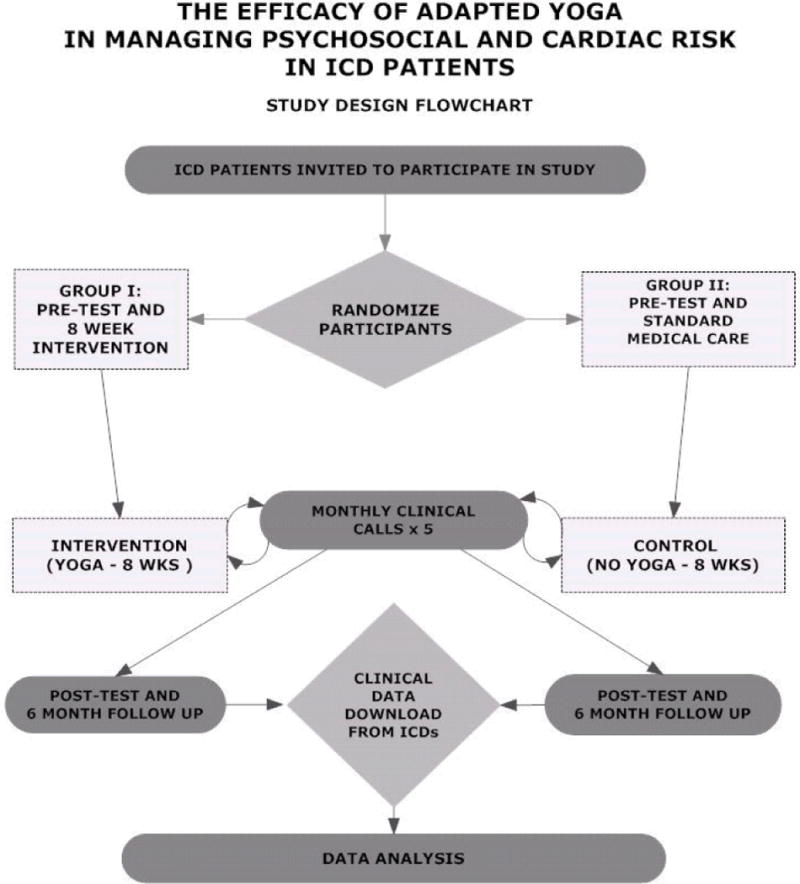

Enrolled participants were randomized into two groups, one receiving only standard medical care (control), the other receiving a program of yoga (intervention) in addition to standard medical care (see Figure 1). Currently, standard care consists of a post-surgical follow-up appointment and regularly scheduled device interrogations every six to nine months or in accordance with the patient’s medical condition. During device interrogation, physiological data stored in the device’s CPU chip is downloaded electronically. The study protocol and all study materials, which included the consent and HIPAA authorization forms (Yale Human Investigation Committee #1211011157), were approved by the Yale-New Haven Hospital, Saint Raphael Campus, Human Subject Investigation Review Board.

Figure 1.

Study design flowchart

The study period consisted of an eight-week intervention and a six-month follow-up post-intervention which consisted of medical data and device interrogation collection. In order to partially control for the amount of personal attention received from hospital staff, participants of both groups also received a monthly call from one of the cardiac nurses commencing at the start of study period. This allowed patients to have contact with clinicians during the study period and three months beyond, ask for and receive information about their devices, and report and discuss any cardiac health issues.

Intervention Design

The yoga program consisted of eight weekly sessions of 80 minutes each. Each session had a pre-planned curriculum that was progressively more challenging and which facilitated adherence and secured repeatability of the intervention. The protocol was administered to four groups of intervention participants and only differed in the start date of the program. The program content was designed specifically for the ICD cardiac population, based on existing adapted yoga programs (Toise SCF, PhD, MPH, unpublished NIH grant, 2007).(18; 19) The program included movements that were consistent with daily life activity. Competitiveness was discouraged. Participants were encouraged to challenge themselves within their level of comfort and mentored to develop body awareness through the class instruction.

The yoga intervention protocol was designed with three different categories of functional ability to provide patients with a range of options consistent with their physical capability: fully assisted, for patients who could not stand or transition from lying to sitting or sitting to standing; partially assisted, for patients who could stand and transition with assistance from lying down to sitting and sitting to standing; unassisted, for patients who could stand and transition from lying down to sitting and sitting to standing without asisstance. (19) However, all three levels included the same material and curriculum, which was adapted to each of the three physical ability categories. This allowed patients with a wide range of physical abilities to participate, making the study population more likely to resemble the general population of ICD recipients.

In addition to these three levels, the curriculum was standardized into a documented and repeatable seven-step protocol in three categories: (1) breathing techniques (pranayama), (2) adapted physical postures (asana), and (3) relaxation (nidra) and meditation. Because these behavioral change techniques improve with practice and frequent practice strengthens the effect, each participant received a 30-minute home practice CD at the second class to facilitate home practice three times a week. At the beginning of each class, participants completed a check-in form and reported on the amount and type of home practice done the previous week. At the end of each class, participants completed a two-minute written check-in, which recorded their emotional state, and a weekly tracking form to record their home practice information.

Control Design

Participants in the control were given standard medical care which consisted of regularly scheduled in-person office visits with device interrogations (the download of electrically stored clinical data) every six to nine months, periodic wireless interrogations, and follow-up from the cardiac nurses for non-routine device findings or medication concerns. In addition, as previously stated, the control group received five monthly calls from the cardiac nursing staff.

Planned Analysis and Data Collection

As this was a pilot study, we were seeking to measure a relatively large effect between the yoga and control groups (Cohen’s d=0.80). We estimated that a sample size of 52 would provide 80% power to detect the hypothesized effect with a two-tailed alpha value of 0.05. To account for a 5% loss to follow-up, we recruited 55 subjects.

Demographic, psychosocial, and medical data were compared between groups (yoga and control) to evaluate the randomization scheme utilized. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test while categorical variables were analyzed with the two-sided Fisher’s exact test. An intention-to-treat approach was used. Correlation coefficients, t-tests, and chi square tests were calculated to determine the association and statistical significance between device programming and number of DTV events. Differences between groups in the change of each psychosocial measure from week 1 (baseline) to week 8 (end of intervention period) were analyzed using Student t-tests as well as generalized linear models. Baseline, intervention, and follow-up medical data were compared using generalized linear models to assess medical differences between the two groups which could be attributed to the yoga intervention. Linear regression was utilized to model the total number of device events recorded by the end of the follow-up period (time 2) as a function of the total number of device events recorded at the start of the study (time 1), group (yoga or control), the interaction of the total number of device events at time 1 and group, as well as age and gender. Data was analyzed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) and SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

At the start of the study, demographic and socioeconomic data were collected using self-report questionnaires and included: age, marital status, education, income, household population, ethnicity, race, and religious attendance. Medical data were collected from the medical record including: ejection fraction (%), indication for ICD implantation (primary or secondary), inappropriate shocks, type and date of device implantation, atrial fibrillations, number of successful DTV events, medications, and all co-morbidities and hospitalizations. Psychological and psychosocial data were collected through the administration of nine validated inventories.

The medical data were collected on all patients at three time points; at baseline; at two months, which represented the end of the intervention period, and at six months after the study period. Medications usage, including anti-arrhythmia, cardiac, anti-depressant, and anti-anxiety medication, were documented at each of these points. Device programming and medication dosing, including cardiac and arrhythmia medication, were optimized by the treating physician to patients’ individual conditions and were independent of their participation in the study. Two hospital cardiologists collected and verified all clinical data, including device programming information, from the medical record. The electrocardiograms and device interrogation data were interpreted by the treating cardiologists and electrophysiologists, respectively.

At the beginning of the study period (pre-test) and again at the end of the study period (post-test), all participants were administered validated measures to assess the psychological and psychosocial components/results of living with the ICD. Additional data were collected on all yoga intervention participants, including information on class attendance and home practices.

Recruitment

Recruitment took place at Yale-New Haven Hospital, Saint Raphael Campus in New Haven, Connecticut, via hospital publicity and the clinical offices of the co-investigators. Saint Raphael’s is a 511-bed urban hospital campus, which performs over 300 ICD implantations per year. The hospital’s magazine, with a circulation of over 200,000, featured an article about ICD and arrhythmic conditions which included mention of this study and was used to reach potential participants in the larger community. Although some potential participants were recruited from responses to the hospital’s media publicity, the majority were recruited by personal interviews in the offices of electrophysiologists.

Inclusion criteria required participants to 18 or more years of age, have an ICD implanted at least six weeks prior, and be deemed ready to participate by their physician. Prospective participants were excluded from the study if: (a) hospitalized for 48 hours or more due to implantation (i.e., atypical treatment course), (b) diagnosed with dementia or mental incompetence, or (c) contraindicated for participation by their physician. Participants were enrolled and consented by two cardiac nurses and the principal investigator. To ensure a uniform, unbiased approach, invitation and consent material approved by the hospital’s investigation review board were used. Participants were randomized by the principal investigator using the coin toss method.

Once consented and randomized, patients were mailed packets with detailed program information and a demographic questionnaire and nine inventories to be completed and returned by mail. The patients were informed that they would be randomly assigned to either a group which would have regular contact with the cardiac nursing team or to a group which would participate in a series of yoga classes. Patients were informed that we were investigating two ways to improve the experience of living with an ICD. The confidential information from the questionnaires was coded upon receipt and entered into a statistical program, as were all collected device and medical data. Patients completed the same nine inventories at the end of their intervention period and returned them by mail.

Participants

Fifty-five patients were enrolled in the study: 31 were randomly assigned to the intervention group and 24 to the standard care control group. In the intervention group, 5 patients declined to participate: 4 gave non-illness related reasons and 1 preferred not to give a reason. In the control group, 4 patients declined to participate: 2 gave no reason, 1 had a cardiac-related illness, and 1 reported family difficulty (see Figure 2) Three patients were excluded from participating in the study: 2 were under the age of consent (18 years), and one had recently sustained a serious back injury for which movement, including yoga, was contraindicated. Recruitment began in April 2008, and the study protocol was completed in January 2011.

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

Data was collected on the patients including age, gender, education, and religious attendance. Table I and II present the specific data on the demographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics of the study participants. The average participant was a male in his late sixties, married, who had not completed college, and who resided with at least two others in the household. Tables I and II present additional data on the demographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

Table I.

Baseline and Demographic Characteristics of Yoga and Control Group Participants

| All (N=46) | Control (n=20) | Yoga (n=26) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Variable | N | % | n | % | n | % | p |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 10 | 12.7 | 2 | 10% | 8 | 31% | 0.09 |

| Male | 36 | 78.3 | 18 | 90% | 18 | 69% | |

| Level of Education | 0.98 | ||||||

| Some High School | 2 | 4.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 3.9 | |

| High School Diploma | 13 | 31.0 | 6 | 37.5 | 7 | 26.9 | |

| Some College | 8 | 19.0 | 3 | 18.8 | 5 | 19.2 | |

| College Diploma | 10 | 23.8 | 3 | 18.8 | 7 | 26.9 | |

| Some Graduate School | 5 | 11.9 | 2 | 12.5 | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Graduate Degree | 4 | 9.5 | 1 | 6.3 | 3 | 11.5 | |

| Marital Status | 0.30 | ||||||

| Single | 2 | 4.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 3.9 | |

| Married | 23 | 54.8 | 8 | 50.0 | 15 | 57.7 | |

| Separated | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.9 | |

| Divorced | 9 | 21.4 | 2 | 12.5 | 7 | 26.9 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 11.9 | 4 | 25.0 | 1 | 3.9 | |

| Other | 2 | 4.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 3.9 | |

| Income | 0.75 | ||||||

| <25k | 3 | 9.4 | 2 | 16.7 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| 25–49k | 7 | 21.9 | 2 | 16.7 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| 50–74k | 7 | 21.9 | 4 | 33.3 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| 75–99k | 6 | 18.8 | 1 | 8.3 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| 100–124k | 4 | 12.5 | 2 | 16.7 | 2 | 10.0 | |

| 125–149k | 3 | 9.4 | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 10.0 | |

| 150–174k | 1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| ≥200k | 1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.0 | |

| Religious Preference | 0.36 | ||||||

| Catholic | 20 | 52.6 | 9 | 60.0 | 11 | 47.8 | |

| Jewish | 4 | 10.5 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Christian Orthodox | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Protestant | 11 | 29.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 9 | 39.1 | |

| None | 2 | 5.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 4.4 | |

| Religious Attendance | 0.49 | ||||||

| Never | 11 | 27.5 | 5 | 31.3 | 6 | 25.0 | |

| Several Times / Year | 13 | 32.5 | 3 | 18.8 | 10 | 41.7 | |

| At Least 1x / Month | 2 | 5.0 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 4.2 | |

| At Least 1x / Week | 14 | 35.0 | 7 | 43.8 | 7 | 29.2 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.30 | ||||||

| Black | 2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.0 | |

| White | 38 | 92.7 | 15 | 93.8 | 23 | 92.0 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Employment Status | 0.54 | ||||||

| Part Time | 3 | 7.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Full Time | 13 | 31.7 | 4 | 25.0 | 9 | 36.0 | |

| Self-Employed | 5 | 12.2 | 1 | 6.3 | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Tobacco | 4 | 9.5 | 2 | 12.5 | 2 | 7.7 | 0.63 |

| Alcohol | 26 | 61.9 | 11 | 68.8 | 15 | 57.7 | 0.53 |

| Own Computer | 34 | 85.0 | 14 | 87.5 | 20 | 83.3 | 1.00 |

Table II.

Baseline Lifestyle and Clinical Measures in Yoga and Control Participants

| All (N=46) | Control (n=20) | Yoga (n=26) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| N | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | df | t | p | |

| Age | 44 | 66.3 | 13.3 | 16 | 69.8 | 14.9 | 26 | 63.3 | 12.0 | 40 | 1.53 | 0.13 |

| No. of Children | 43 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 16 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 25 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 39 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| No. Living in Household | 42 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 16 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 24 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 19.58c | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Alcohol: (Glasses/ Month) | 43 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 15 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 26 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 39 | –0.05 | 0.96 |

| Ejection Fraction | 25 | 34.2 | 14.7 | 12 | 35.4 | 15.0 | 13 | 33.1 | 14.9 | 23 | 0.39 | 0.70 |

| No. of Successful ATPs | 46 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 20 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 26 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 24.63c | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| No. ofMorbiditiesa | 46 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 26 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 44 | –1.93 | 0.06 |

| No. ofMedicationsb | 46 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 20 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 26 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 42.74c | –1.34 | 0.14 |

No.= number

M = mean

SD = standard deviation

- Each co-morbidity was grouped into one of eight categories (cancer, cardiovascular disease, endocrine disorder, gastrointestinal disease, genitourinary disease, mental health disorder, neurological disorder, pulmonary disease).

- Based upon the comorbidities listed for each subject, each of the eight categories were either present (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0).

- The coded categories were then summed to determine the total number of morbidities for each subject.

= Number of Medications calculated by summing the number of medication categories (antianxiety, antidepressant, class1A, class1B, class1C, class II beta blocker, class III) that a subject was taking.

= df calculated using Satterthwaite Approximation.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Device-specific anxiety was the primary psychosocial outcome, as measured by the change over time, along with eight other secondary psychosocial risk factors. The measure of DTV events was the primary cardiac outcome, which was assessed by measuring the change in the number of occurrences that required ICD activation over time. The observed events would be followed for a total of eight months: during the two-month intervention period and through a six month follow-up period. DTV events were comprised of anti-tachycardia pacing and shock events. Inappropriate device firings, including atrial events, were also recorded and removed from the event totals.

Psychological and Psychosocial Measures

The following nine validated inventories were used to measure psychosocial risk factors of cardiovascular disease, including device-specific concerns: Florida Shock Anxiety Scale(20); Florida Patient Acceptance Survey(21); Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (22–24); Positive Health Expectation Scale(25); State-Trait Personality Inventory (Spielberger CD, PhD, unpublished manuscript, 1979)(2; 26; 27); Interpersonal Support Evaluation(28; 29); Self-Compassion Scale(30); Symptom Emotion Check-list(31); and Expression Manipulation Test.(32) Two of these inventories merit additional description because of their relevance to the findings of this study.

Florida Shock Anxiety Scale

The Florida Shock Anxiety Scale (FSAS), a well-validated inventory, measures the level of shock-specific anxiety experienced by participants in a 10-item self-report scale.(20)There is a total scale score and two subscale measures, mean consequence and mean trigger score. Specifically, the mean consequence subscale measures the amount of anxiety the patient feels living with the ICD, and the mean trigger measures the amount of anxiety the patient has about not knowing when the device will fire. In this study, the FSAS was employed to measure whether the yoga intervention affected levels of shock anxiety in participants.

Self-Compassion Scale

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) is a 26-item self-report scale with six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identified. It is “a valid and useful way to conceptualize and to measure healthy self-attitude.”(30 p.236) Negative items are reverse-scored. A higher score indicates greater self-compassion, which significantly correlates with positive mental health outcomes such as reduced anxiety and greater life satisfaction. (30)

Medical History and Measures

The medical status of participants was analyzed to see what effect, if any, the intervention had on cardiac outcomes. There were six medical categories: diagnosis, device activity, co-morbidities, medications, hospitalizations, and cardiac function.

Medical record review was completed to code the following variables. Co-morbidities were grouped into these categories: cancer, cardiovascular disease, endocrine disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, genitourinary diseases, mental health disorders, neurological disorders, and pulmonary diseases. Type of medication used by participants was also recorded for analysis and included: anti-depressants; anti-anxiety drugs; anti-arrhythmic medication classes 1A, B, and C; beta blockers; class III anti-arrhythmia drugs; and the drug digoxin. Hospitalizations, both cardiac and non-cardiac, were recorded, as well as indication for ICD implantation status for primary or secondary prevention and time since ICD procedure. The number of atrial fibrillations, ventricular tachycardia, anti-tachycardia events, and device firings were followed for analysis. The ejection fractions of participants, obtained from echocardiograms, were collected.

Analysis

Baseline Statistical Analysis

Scores on the psychosocial and medical measures for the yoga intervention and control groups were compared at the beginning of the study. Tables III and IV present a more detailed description of the baseline co-morbidities and psychosocial measures of the study participants. Categorical variables were compared using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-tests. None of the major categories showed statistical difference.

Table III.

Baseline Co-Morbidities in Yoga and Control Participants

| All (N=46) | Control (n=20) | Yoga (n=26) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | pa | |

| Prophylactic ICD Implant | 26 | 56.52 | 9 | 45.00 | 17 | 65.38 | 0.23 |

| Received Shock | 2 | 4.35 | 1 | 5.00 | 1 | 3.85 | 1.00 |

| AF | |||||||

| None | 39 | 84.78 | 18 | 90.00 | 21 | 80.77 | 0.68 |

| Multiple | 2 | 4.35 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 7.69 | |

| Chronic / 100% | 5 | 10.87 | 2 | 10.00 | 3 | 11.54 | |

| Comorbid Diseases | |||||||

| Cancer | 2 | 4.35 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 7.69 | 0.50 |

| Cardiovascular | 37 | 80.43 | 16 | 80.00 | 21 | 80.77 | 1.00 |

| Endocrine Disorder | 19 | 41.30 | 7 | 35.00 | 12 | 46.15 | 0.55 |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 | 4.35 | 1 | 5.00 | 1 | 3.85 | 1.00 |

| Genitourinary | 3 | 6.52 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 11.54 | 0.25 |

| Mental Health Disorder | 1 | 2.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 3.85 | 1.00 |

| Neurological Disorder | 2 | 4.35 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 7.69 | 0.50 |

| Pulmonary | 11 | 23.91 | 4 | 20.00 | 7 | 26.92 | 0.73 |

| Medications | |||||||

| Antianxiety | 1 | 2.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 3.85 | 1.00 |

| Antidepressant | 10 | 21.74 | 4 | 20.00 | 6 | 23.08 | 1.00 |

| Class 1A | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Class 1B | 5 | 10.87 | 2 | 10.00 | 3 | 11.54 | 1.00 |

| Class 1C | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Class II Beta Blocker | 39 | 84.78 | 16 | 80.00 | 23 | 88.46 | 0.68 |

| Class III | 16 | 34.78 | 5 | 25.00 | 11 | 42.31 | 0.35 |

| Digoxin | 8 | 17.39 | 3 | 15.00 | 5 | 19.23 | 1.00 |

Table IV.

Baseline Psychosocial Measures in Yoga and Control Participants

| All (N=46) | Controls (n=26) | Yoga (n=20) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Measure/Subscale | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | df | t | p |

| CES-D | 43 | 11.40 | 10.18 | 15 | 8.60 | 6.13 | 26 | 13.73 | 11.64 | 39 | –1.85 | 0.07 |

| FPAS | ||||||||||||

| Total | 42 | 85.16 | 20.10 | 14 | 88.21 | 22.21 | 26 | 83.40 | 19.88 | 38 | 0.70 | 0.49 |

| Return to Life | 42 | 69.79 | 24.57 | 14 | 72.77 | 24.59 | 26 | 68.27 | 25.61 | 38 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| Device Stress | 41 | 81.34 | 26.48 | 13 | 88.85 | 21.62 | 26 | 73.73 | 28.84 | 37 | 1.34 | 0.19 |

| Positive Appraisal | 42 | 84.23 | 20.30 | 14 | 92.41 | 10.74 | 26 | 80.77 | 23.38 | 37 | 2.15 | 0.04 |

| Body Image Concern | 41 | 79.27 | 26.75 | 13 | 75.00 | 31.04 | 26 | 80.77 | 25.55 | 37 | –0.62 | 0.54 |

| PHE | 42 | 41.02 | 7.61 | 14 | 42.79 | 6.13 | 26 | 40.04 | 8.38 | 38 | 1.08 | 0.29 |

| STPI | 43 | 62.79 | 21.10 | 15 | 58.53 | 16.76 | 26 | 67.08 | 22.69 | 39 | –1.27 | 0.21 |

| SEC | 43 | 17.77 | 8.58 | 15 | 18.00 | 10.90 | 26 | 17.63 | 7.42 | 39 | 0.11 | 0.91 |

| FSAS | ||||||||||||

| Total | 42 | 15.29 | 7.89 | 14 | 12.86 | 4.38 | 26 | 16.96 | 9.17 | 37.674 | –1.91 | 0.06 |

| Mean Consequence | 42 | 1.28 | 0.71 | 14 | 1.04 | 0.45 | 26 | 1.43 | 0.81 | 38 | –1.96 | 0.06 |

| Mean Trigger | 42 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 14 | 1.31 | 1.04 | 26 | 1.56 | 1.04 | 38 | –0.74 | 0.46 |

| SCS | ||||||||||||

| Total | 43 | 3.42 | 0.70 | 15 | 3.60 | 0.63 | 26 | 3.27 | 0.72 | 39 | 1.47 | 0.15 |

| Self-Kindness | 43 | 2.96 | 0.91 | 15 | 2.93 | 0.88 | 26 | 2.96 | 0.97 | 39 | –0.09 | 0.93 |

| Self-Judgment | 43 | 2.50 | 0.96 | 15 | 2.11 | 0.79 | 26 | 2.71 | 1.00 | 39 | –1.99 | 0.05 |

| Comhumanity | 43 | 3.07 | 1.01 | 15 | 2.93 | 1.10 | 26 | 3.17 | 1.00 | 39 | –0.71 | 0.48 |

| Isolation | 43 | 2.27 | 0.98 | 15 | 1.92 | 0.80 | 26 | 2.51 | 1.05 | 39 | –1.89 | 0.07 |

| Mindfulness | 43 | 3.38 | 0.97 | 15 | 3.52 | 1.00 | 26 | 3.29 | 0.92 | 39 | 0.74 | 0.46 |

| Overidentified | 43 | 2.16 | 0.93 | 15 | 2.03 | 0.87 | 26 | 2.29 | 0.97 | 39 | –0.84 | 0.40 |

| EMT Cue response | 33 | 1.79 | 0.42 | 10 | 1.60 | 0.52 | 21 | 1.86 | 0.36 | 29 | –1.62 | 0.12 |

| IPS | ||||||||||||

| Total | 46 | 7.33 | 2.23 | 18 | 6.72 | 2.87 | 26 | 7.85 | 1.64 | 24.735 | –1.50 | 0.15 |

| Appraisal | 43 | 2.30 | 0.60 | 15 | 2.40 | 0.74 | 26 | 2.27 | 0.53 | 39 | 0.66 | 0.52 |

| Belong | 43 | 2.30 | 0.60 | 15 | 2.40 | 0.63 | 26 | 2.27 | 0.60 | 39 | 0.66 | 0.52 |

| Tangible | 43 | 2.11 | 0.32 | 15 | 2.13 | 0.35 | 26 | 2.12 | 0.33 | 39 | 0.17 | 0.87 |

| Esteem | 42 | 1.29 | 0.46 | 15 | 1.20 | 0.41 | 25 | 1.36 | 0.49 | 38 | –1.06 | 0.30 |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; FPAS = Florida Patient Acceptance Survey; PHE = Positive Health Expectation Scale; STPI = State-Trait Personality Inventory; SEC = Symptom/Emotion Checklist; FSAS = Florida Shock Anxiety Scale; SCS = Self-Compassion Scale; EMT = Expression Manipulation Test; IPS = Interpersonal Support Evaluation

Analysis of Hypotheses

To test the first hypothesis – that the adapted yoga intervention would reduce psychosocial stress measured at follow-up – a series of Student’s t-tests were performed to determine if the mean changes between the two groups were significantly different. The study also hypothesized that the intervention would significantly impact the relationship between baseline risk factors and subsequent device episodes. Multiple regression was performed using age, gender, and number of episodes to predict subsequent device episodes.

Additionally, linear and logistic regression models analyses were conducted utilizing the following dependent variables: DTV events, atrial fibrillation, total morbidities, total medication, anxiety medications, antidepressants, anti-arrhythmia drugs, Class II beta blockers, total hospitalizations, cardiac hospitalizations, and non-cardiac hospitalizations.

Analysis of Outcome Variables

The analyses in this study yielded sizable quantities of data in two areas, psychosocial and medical. There were nine psychosocial categories, six medical categories, and eight co-morbidities categories. Analyses comparing the control and yoga group are discussed below. These outcomes reflect the changes of patients over time, compared between the intervention and control groups.

Results

Participation

All 26 participants assigned to the yoga group attended at least one class. One patient attended only a single class; however, the remaining 25 participants in the yoga group had robust participation over the course of the intervention. The median number of classes that the 26 participants attended was 7 out of the possible 8 class sessions. The median number of times these participants practiced at home was 16 times out of the possible21 scheduled home practice sessions. Over the course of the eight week study period the participants had a mean practice time of 20 minutes a day.

Psychosocial Results

Results demonstrated that the intervention group decreased in overall (total) device-specific anxiety while the control group increased in total device-specific anxiety, as shown in Table V. The FSAS total scale measuresthe amount of anxiety recipients reported feeling about living day-to-day with the ICDand the amount of anxiety patients have about not knowing when the device will fire. This total included scores from both subscales, mean consequence and mean trigger. Furthermore, significant positive results were also found in the mean consequence subscale itself. The mean score changes showed a marked decrease for the intervention group in mean consequence anxiety and an increase in the same anxiety for the control group (Figure 3).

Table V.

Pre-Post Mean Change on Psychosocial Measures in Yoga and Control Participants

| Controls | Yoga | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Measure/Subscale | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | df | t | p |

| CES-D | 14 | 2.00 | 5.33 | 26 | –2.77 | 8.85 | 38 | 1.84 | 0.074 |

| FPAS | |||||||||

| Total | 14 | –3.33 | 23.06 | 26 | 4.94 | 17.81 | 38 | –1.26 | 0.215 |

| Return to Life | 14 | –1.79 | 22.92 | 26 | 4.57 | 21.40 | 38.00 | –0.87 | 0.388 |

| Device Stress | 13 | 0.00 | 12.75 | 26 | 5.58 | 19.56 | 37 | –0.93 | 0.358 |

| Positive Appraisal | 14 | –20.09 | 38.70 | 26 | 3.37 | 30.12 | 38 | –2.12 | 0.040* |

| Body Image Concern | 20 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 26 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 44 | –1.18 | 0.244 |

| PHE | 20 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 26 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 44.00 | –0.04 | 0.972 |

| STPI | 14 | –1.36 | 7.90 | 25 | –3.44 | 11.15 | 37 | 0.62 | 0.542 |

| SEC | 14 | –3.71 | 11.80 | 25 | –0.08 | 6.53 | 17.56 | –1.06 | 0.302 |

| FSAS | |||||||||

| Total | 13 | 3.00 | 2.08 | 25 | –1.24 | 3.82 | 35.855 | 4.43 | <.0001** |

| Mean Consequence | 13 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 25 | –0.16 | 0.38 | 36 | 2.86 | 0.007** |

| Mean Trigger | 13 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 25 | –0.11 | 0.47 | 36.000 | 1.87 | 0.069 |

| SCS | |||||||||

| Total | 14 | –0.29 | 0.61 | 25 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 37 | –2.84 | 0.007** |

| Self-Kindness | 14 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 25 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 37 | –0.12 | 0.906 |

| Self-Judgment | 14 | 0.51 | 1.10 | 25 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 37 | 1.58 | 0.123 |

| Comhumanity | 14 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 37 | –0.36 | 0.720 |

| Isolation | 14 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 25 | –0.20 | 0.76 | 37.00 | 1.78 | 0.084 |

| Mindfulness | 14 | –0.04 | 0.77 | 25 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 37 | –2.10 | 0.042* |

| Overidentified | 14 | 0.41 | 1.05 | 25 | –0.13 | 0.50 | 16.38 | 1.82 | 0.088 |

| EMT Cue response | 9 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 20 | –0.10 | 0.55 | 27.00 | 1.06 | 0.300 |

| IPS | |||||||||

| Total | 16 | 1.00 | 2.94 | 22 | –0.18 | 0.96 | 17.33 | 1.55 | 0.140 |

| Appraisal | 13 | –0.23 | 0.73 | 22 | –0.14 | 0.77 | 33 | –0.36 | 0.724 |

| Belong | 13 | –0.23 | 0.44 | 22 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 33.00 | –1.18 | 0.246 |

| Tangible | 13 | –0.08 | 0.28 | 22 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 33 | –1.02 | 0.315 |

| Esteem | 13 | 0.08 | 0.64 | 21 | –0.05 | 0.22 | 13.74 | 0.68 | 0.510 |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; FPAS = Florida Patient Acceptance Survey; PHE = Positive Health Expectation Scale; STPI = State-Trait Personality Inventory; SEC = Symptom/Emotion Checklist; FSAS = Florida Shock Anxiety Scale; SCS = Self-Compassion Scale; EMT = Expression Manipulation Test; IPS = Interpersonal Support Evaluation

Figure 3.

T-tests comparing mean change from baseline to post-test; (top left) T-test comparing mean change of Florida Shock Anxiety Scale (FSAS) Total from baseline to post-test; (top right) T-test comparing mean change of Florida Shock Anxiety Scale (FSAS) Mean Consequence from baseline to post-test; (bottom left)T-test comparing mean change of Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) Total from baseline to post-test; (bottom right)T-test comparing mean change of Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) Mindfulness from baseline to post-test.

The SCS inventory measures self-compassion, or how patients treat themselves in times of difficulty. As the outcomes in Table V show, the intervention group reported feeling more self-compassion and the control group reported feeling less (Figure 3).

A subscale of the SCS, mindfulness, also presented as statistically significant as shown in Table V. This subscale measures the quality of having a balanced, non-judgmental perspective of oneself and one’s condition. In a comparison of the outcome between the two groups, the mean score changes demonstrated increased mindfulness in the intervention group and decreased mindfulness in the control group (Figure 3).

Non-significant Psychosocial Results

According to the results of the outcome analyses, the remaining seven scales (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Florida Patient Acceptance Survey [FPAS], Positive Health Expectation Scale, State-Trait Personality Inventory, Symptom/Emotion Checklist, Expression Manipulation Test, and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation) failed to demonstrate that the intervention had an effect on the recipients. Student’s t-tests were used to measure the mean change in all psychosocial measures shown in Table V. The mean change for the FPAS positive appraisal subscale appears statistically significant (see Table V). However, Table IV shows that the baseline measures were unequal. Because of this discrepancy, the results of this subscale were discharged as unreliable.

Relevant Cardiac Findings

Exploratory analyses utilizing a multiple regression linear model of the observed DTV events through the six month follow-up period revealed that the expected number of DTV events in the yoga intervention group was significantly lower than in the control group. This finding is strengthened because factors that could influence DTV events, such as primary or secondary implantation, device programming, and the use of anti-arrhythmia and cardiac medication were confirmed to be randomized at the start of the study. The data was likewise cleaned to remove inappropriate shocks from event analysis: suspect events were flagged by device technicians, analyzed by cardiologists, and confirmed by EPs.

In this linear model, the expected number of DTV events increased more rapidly as a function of the initial DTV events for the control group than it did for the intervention group, parameter estimate of −8.13, t(–16.83, 1), p < 0.0001. The linear model had an R2 = 0.98. The dotted lines in Figure 4 represent the 95% confidence interval. There is a strong inverse statistical relationship between successful DTV events and the yoga intervention group.

Figure 4.

Generalized linear model of expected number of device-treated pacing events (DTV events)

Sixty Year Old Male

R2=0.98

Dotted line=95% confidence interval

T1= week 1

T2=week 8 + six month follow-up period

Therefore, the number of DTV events that could be expected would increase rapidly for those in the control group, but would increase very slowly for those in the intervention group. Whereas the number of DTV events did not change in the yoga intervention group pre to post, relative to controls, yoga participants evidenced fewer firings at follow-up. Based on the regression model used to predict the number of DTV events, persons participating in the yoga intervention had a 32% lower risk relative to controls of experiencing device-related firings by the end of the follow-up period.

Non-significant Medical Findings

Regression analyses were conducted to determine if changes occurred between baseline and six-month follow-up on cardiac outcome variables. The results of these analyses revealed no significant changes for the yoga intervention or control groups with regard to atrial fibrillation, total morbidities, cardiac or non-cardiac hospitalizations, or any of the following types and/or classes of medications: anti-anxiety, anti-depressant, anti-arrhythmia, and beta blockers. Generalized linear models were constructed where the dependent variable was the change in the measure and the independent variable was the type of intervention. The models were adjusted to account for the effects of age and gender. Multivariate logistic regression was used for binary outcomes, again controlling for gender and age. The Spearman correlation between the participants’ initial device settings and total DTV was ‐0.37 (p < .05), indicating that the higher the initial device setting, the fewer DTVs occurred. However, there was no significant difference in participants’ initial device setting between yoga and control participants [t(44)= −0.42, p = .68], nor was there a significant relationship between the number of zones and the intervention group [X2(2)=1.62, p = 0.45]. Moreover, the relationship between the number of programmed device zones and total DTVs (rho=.18) and device zone and baseline DTVs (rho=.11) were non-significant. These findings indicate that neither the initial device setting nor the number of zones would account for the observed differences between the yoga and control groups.

Discussion

The results of this investigation suggest that the yoga intervention was an effective treatment for reducing shock anxiety, for increasing self-compassion, and for reducing the number of DTV events for ICD recipients. This is consistent with research by Lampert, et al., which has shown that psychological factors can be associated with arrhythmias requiring ICD termination. (8) Statistically, the reduction in shock anxiety and increase in self-compassion in the intervention group were significant, and the benefits appear to be attributable to the intervention. While the yoga group improved on shock anxiety and self-compassion, the control group experienced the opposite. The yoga intervention group also experienced an increased sense of equanimity or mindfulness, which is a core tenet of yoga. These outcomes in the yoga intervention group are noteworthy, given the level of anxiety that is present in the ICD population generally, and the fact that ICDs are considered the best treatment for cardiac arrhythmias.(1) In fact, research results published while this study was underway found that “anxiety seems to be more prevalent in cardioverter–defibrillator patients than depression, with prevalence rates of anxiety reported from 24–87% compared to 24–33% for depressive symptoms.”(33 p.39) Another recent study indicated that disease-specific anxiety was independently important in that it predicts poor perceived health outcomes differently than general anxiety measures in ICD recipients: it was particularly associated with feelings of disability and cardiopulmonary complaints.(34) These new finding corroborate the deleterious effects that ICD-specific anxiety may have on recipients, both mentally and physically, making the findings of this investigation even more relevant as a possible way to reduce morbidity and mortality in the ICD population. Our study suggests yoga was particularly valuable in aiding ICD-specific adjustment.

The most intriguing and encouraging cardiac finding related to the yoga intervention group was the multiple regression model predicting fewer DTV events for the intervention group than the control group. Poole, Johnson, and Hellkamp, et al. concluded in their clinical study that “among patients with heart failure in whom an ICD is implanted for primary prevention, those who receive shocks for any arrhythmia have a substantially higher risk of death than similar patients who do not receive such shocks.”(35 p.1009) Additionally, once shocked, patients have a higher risk of late non-sudden cardiac death. (36) Because DTV events are triggered by pro-arrhythmic states, they are a likely indicator of the severity of underlying heart disease. The results of our study suggest that the yoga intervention may have a role in mitigating the severity of the participants’ arrhythmic conditions.

Participants in the yoga intervention were more likely to maintain physical activity because they reported less concern that their behaviors would trigger device firing, allowing them to progress in their recovery. The control group was more likely to report functional impairment and anxiety about physical ailments.

The study had several notable strengths. Its design included the development of an adapted yoga program specific to the ICD population that allowed for implementation with patients at varying levels of cardiovascular functioning and physical conditioning; randomization of patients into control and yoga intervention groups; a standardized and repeatable intervention protocol; a comprehensive follow-up of medical outcomes at six months after the intervention period for both groups; and use of well-validated psychological measures previously employed with and specific to the ICD population, such as FSAS and the FPAS. The strengths in the execution and analyses built on the assets of the study design. The study’s documented protocol of adapted yoga was used consistently and there was no physical ability requirement for participants. The high level of reported compliance in this study is noteworthy in demonstrating that ICD recipients were willing to participate in a yoga program. Outcomes were measured using well-validated ICD-specific measures. Randomization was confirmed to be successful at baseline in the two groups on medical and psychosocial factors including cardiac medication use and device programming zones. In addition to randomization, extensive analyses were conducted in order to rule out alternative explanations for the observed findings. Both the design and implementation of this investigation, in conjunction with observed outcomes, provide information for guiding future studies using adapted yoga in this population.

Limitations

The limitations include a modest sample size, limited time frame in which to follow patients, and a travel requirement to participate in the intervention (which limited the potential study pool to those who could drive or who lived close enough to participate, though a few participants commuted more than one hour.) This could potentially bias the overall study population in favor of participants who had greater independence or stronger interpersonal support. The length of the follow-up period for this studylimited the medical data collection on long-term changes in medications, health status, and device activity. Consequently, health status, such as morbidities, and device activity, such as number of device firings, were only followed for eleven months. This time frame is too short to follow morbidities of many chronic diseases. Device activity data, as well as the measures listedabove, would be more comprehensive over a longer period of follow-up.

This study partially controlled for attention in the control group through monthly telephone interviews and scheduled interrogations with the study’s clinical staff. Thus, the control participants received regular contact with clinicians as part of the study and had multiple opportunities to talk with someone and get additional information about their devices. However, these participants did not attend weekly classes and may or may not have had direct contact with other ICD recipients.

Conclusion

This investigation examined the potential value of yoga in affecting psychosocial and medical parameters in the ICD population. The results demonstrate psychological benefits from a program of adapted yoga, compared to usual care, for ICD recipients, who are at risk for developing elevated levels of psychological stress, accompanied by increased risk for morbidity and mortality. Marked improvements were reported in total shock anxiety, self-compassion, and equanimity.

Yoga participants’ overall shock anxiety decreased while the control group’s increased. The yoga group also had greater overall self-compassion, greater equanimity, and a 32% lower risk, relative to the control group, of experiencing device-related firings at the end of the follow-up period. To wit, the participants in the yoga intervention were less likely to require action from the ICD to regulate heart function.

The results from this study demonstrate both cardiac and psychosocial improvements from a yoga intervention for ICD patients. Future studies with a larger sample size and a longer follow-up period at multiple study sites are warranted. The present study supports further inquiry to better understand how ICD-specific psychosocial stress contributes to cardiovascular outcomes and the role that complementary medicine can play in addressing that stress.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yale New Haven Hospital, Campus of Saint Raphael for hosting this research. The authors would also like to thank Anna Andreozzi, Nancy Casella, Marisa Serensen, Dr. Andre Ghantous, Dr. Eric Grubman, Dr. Barth Riley, Dr. Suddhir Reddy, and Dr. Sabrina Sawhney for their clinical support and contribution to data collection; Amy Murphy for assistance in the conduct of the study; Dr. James Laird and Dr. Roger Bibacefor mentorship, and Jennifer Barricklow for extraordinary editorial support.

Funding Support: Dr. Toise received funds from the Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Grant Number F31AT003757 and the American Association of University Women

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- DTV

Device-treated ventricular [events]

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- EMT

Expression Manipulation Test

- FPAS

Florida Patient Acceptance Survey

- FSAS

Florida Shock Anxiety Scale

- ICD

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- IPS

Interpersonal Support Evaluation

- PHE

Positive Health Expectation Scale

- SCS

Self-Compassion Scale

- SEC

Symptom/Emotion Checklist

- STPI

State-Trait Personality Inventory

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Sears consults with and has research grants from Medtronic. All funds from Medtronic are directed to East Carolina University. He has received speaker honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Biotronik.

This study’s clinical trial registration information is ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT01716351

Author Contributions

Stefanie C.F. Toise, PhD, MPH, E-RYT 500: Concept/design, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, first draft on article, critical revision of article, statistics, funding, approval of article; Samuel F. Sears, PhD:Data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article, approval of article; Mark H. Schoenfeld, MD: Data collection, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article;Mark L. Blitzer, MD:Data collection, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article; Mark A. Marieb, MD:Data collection, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article; John H. Drury, MD: Concept/design, funding, data collection, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article; Martin D. Slade, MPH: Data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of article, statistics, approval of article; Thomas J. Donohue, MD:Clinical sponsor/supervisor, mentor, funding, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol and all study materials, which included the consent and HIPAA authorization forms (Yale Human Investigation Committee #1211011157), were approved by the Yale New Haven Hospital, Campus of Saint Raphael, Human Subject Investigation Review Board.

References

- 1.The AVID Investigators. Causes of death in the Antiarrythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1552–1559. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace RL, Sears SFJ, Lewis TS, Griffis JT, Curtis A, Conti JB. Predictors of quality of life in long-term recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2002;22:278–281. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zayac S, Finch N. Recipients’ of implanted cardioverter-defibrillators actual and perceived adaptation: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:549–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sears SF, Jr, Todaro JF, Lewis TS, Sotile W, Conti JB. Examining the psychosocial impact of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a literature review. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:481–489. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960220709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke JL, Hallas CN, Clark-Carter D, White D, Connelly D. The psychosocial impact of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator: a meta-analytic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2003;8:165–178. doi: 10.1348/135910703321649141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilge AK, Ozben B, Demircan S, Cinar M, Yilmaz E, Adalet K. Depression and anxiety status of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator and precipitating factors. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sears SF, Matchett M, Conti JB. Effective management of ICD patient psychosocial issues and patient critical events. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1297–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lampert R, Shusterman V, Burg M, McPherson C, Batsford W, Goldberg A, Soufer R. Anger-induced T-wave alternans predicts future ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009. 2009;53:774–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Januzzi JL, Jr, Stern TA, Pasternak RC, DeSanctis RW. The influence of anxiety and depression on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1913–1921. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Boven AJ, Jukema JW, Haaksma J, Zwinderman AH, Crijns HJGM, Kong I. Depressed heart rate variability is associated with events in patients with stable coronary artery disease and preserved left ventricular function. Am Heart J. 1998;135:571–576. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lampert R, Joska T, Burg MM, Batsford WP, McPherson CA, Jain D. Emotional and Physical Precipitants of Ventricular Arrhythmia Circulation. 2002;106:1800–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031733.51374.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Innes KE, Vincent HK. The influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel103. Advanced Access published December 11, 2006; 1–18. http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/4/4/469. Accessed August 12, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gupta N, Khera S, Vempati RP, Sharma R, Bijlani RL. Effect of yoga based lifestyle intervention on state and trait anxiety. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;50:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:849–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalsa SB. Treatment of chronic insomnia with yoga: a preliminary study with sleep-wake diaries. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s10484-004-0387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabhade A, Pawar B, Ghunage M, Ghunage V. Effect of pranayama (breathing exercise) on arrhythmias in the human heart. Explore. 2012;8:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devi N. The healing path of yoga: time-honored wisdom and scientifically proven methods that alleviate stress, open your heart, and enrich your life. New York: Three Rivers Press; 2000. pp. 143–181. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toise S. Proceedings of the First International Symposium of International Association of Yoga Therapists. Los Angeles, CA: Jan 18–21, 2007. The design and implementation of a hospital-based therapeutic yoga rehabilitation program: a case report. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhl EA, Dixit NK, Walker RL, Conti JB, Sears SF. Measurement of patient fears about implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock: an initial evaluation of the Florida Shock Anxiety Scale. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:614–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen SS, Spindler H, Johansen JB, Mortensen PT, Sears SF. Correlates of patient acceptance of the cardioverter defibrillator: cross-validation of the Florida Patient Acceptance Survey in Danish patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:1168–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Measure. 1997;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ensel W. Measuring depression: the CES-D scale. In: Lin N, et al., editors. Social support, life events, and depression. New York: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Honig A, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W. Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:221–227. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sears SF, Serber ES, Lewis TS, Walker RL, Conners N, Lee JT, Curtis AB, Conti JB. Do positive health expectations and optimism relate to quality of life outcomes in ICD patients? J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:324–33. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams JE, Paton CC, Siegler IC, Eigenbrodt ML, Nieto FJ, Tyroler HA. Anger proneness predicts coronary heart disease risk: prospective analysis from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2000;101:2034–2039. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams JE, Nieto FJ, Sanford CP, Couper DJ, Tyroler HA. The association between trait anger and incident stroke risk: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2002;33:13–19. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, et al., editors. Social support: theory, research, and applications. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 13–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sears SF, Lewis TS, Kuhl EA, Conti JB. Predictors of quality of life in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:451–457. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–250. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennebaker J. The Psychology of Physical Symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1982. pp. 165–167. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strout SL, Bush SE, Laird JD. Proceeding of the annual meeting of the International Society for Research on Emotion. New York, NY: Jul 7–11, 2004. Differences in the experience of emotion. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen SS, Van den Berg H, Theuns DA, Erdmann E, Alings M, Meijer A, Jordaens L, et al. Risk of chronic anxiety in implantable defibrillator patients: a multi-center study. Int J Cardiol. 2009;33:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Broek KC, Nyklicek I, Denollet J. Anxiety predicts poor perceived health in patients with an implantable defibrillator. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:483–492. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sweeney M, Sherfesee L, DeGRoot P, Wathen M, Wilkoff B. Differences in effects of electricial therapy type for ventricular arrhythmias on mortaliaty in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]