Abstract

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and potential mechanism of action of type-II collagen bifunctional peptide inhibitor (CII-BPI) molecules in suppressing rheumatoid arthritis in the collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mouse model. CII-BPI molecules (CII-BPI-1, CII-BPI-2, and CII-BPI-3) were formed through conjugation between an antigenic peptide derived from type-II collagen and a cell adhesion peptide LABL (CD11a237-246) from the I-domain of LFA-1 via a linker molecule. The hypothesis is that the CII-BPI molecules simultaneously bind to MHC-II and ICAM-1 on the surface of APC and block maturation of the immunological synapse. As a result, the differentiation of naïve T cells is altered from inflammatory to regulatory and/or suppressor T cells. The efficacies of CII-BPI molecules were evaluated upon intravenous injections in CIA mice. Results showed that CII-BPI-1 and CIIBPI-2 suppressed the joint inflammations in CIA mice in a dose-dependent manner and were more potent than the respective antigenic peptides alone. CII-BPI-3 was not as efficacious as CII-BPI-1 and CII-BPI-2. Significantly less joint damage was observed in CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 treated mice than in the control. The production of IL-6 was significantly lower at the peak of disease in mice treated with CII-BPI-2 compared to those treated with CII-2 and control. In conclusion, this is the first proof-of-concept study showing that BPI molecules can be used to suppress RA and may be a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Rheumatoid arthritis, Bifunctional peptide inhibitors, T cells, Interleukin-6

Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that causes pain, stiffness, chronic inflammation, and deformity due to cartilage, bone, and ligament destruction in the joints [1]. Although the etiology of RA is not fully understood, it has been suggested that the cause of the disease is the attack on the host joints by immune cells along with the generation of lymphocytes that release inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1, IL-6 [2-5]. Th1 cells infiltrate the synovium where they release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that promote macrophage and neutrophil infiltration and activation [1,4,6]. Th17 cells, a subset of Th cells, have also been implicated in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis [3,7]. Another possible cause is that the body fails to activate regulatory T cells (T-reg); thus, enhancing the production of T-reg may be one therapeutic strategy to suppress RA and other autoimmune diseases [8-12].

Many treatments are available for preventing joint degradation and inflammation; however, there is not yet a cure for RA. Some of the drugs used in the treatment of RA include Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and traditional Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDS) [13-15]. Methotrexate is one of the most commonly used traditional DMARD. Although it is effective, its use is sometimes discontinued due to toxicity. It is reported that approximately 30% of RA patients abandon treatment because of toxicity issues [16]. There are also newer biological DMARDS (e.g., etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, rituximab, and abatacept) that have been used in the treatment of RA. Biologic modifiers provide therapeutic response via lowering TNF-α levels in the systemic circulation [17,18], blocking T-cell activation [13,14,19,20], and depleting B cells [21,22]. With the advent of these targeted therapies used alone or in combination with other drugs [13,14], standard care for patients with RA has markedly improved. However, many patients still experience less than adequate control because they either do not respond to treatment or become resistant to it. Also, some patients respond to the treatments, but develop complications due to undesirable drug safety profiles. Safety of RA therapies is always a concern because most of these treatments are generally immunosuppressive causing a risk of opportunistic infection or increased serious adverse side effects.

Further improvement in RA treatment and management can be achieved through introduction of innovative therapies that provide better efficacy and safety profiles. Our group discovered a new strategy to suppress or prevent the development of autoimmune diseases by controlling the activation of immune cells in an antigen-specific manner using Bifunctional Peptide Inhibitor (BPI) molecules [23-28]. In this strategy, a cell adhesion molecule is conjugated to an antigenic peptide via a spacer to make BPI molecules. Studies on PLP-BPI and GAD-BPI have been shown to induce immunotolerance in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) and type-1 diabetes (T1D), respectively [23-28].

In this study, we investigated the potential of using BPI molecules to induce tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. We developed a novel type of bifunctional peptide inhibitor (BPI) molecule called CII-BPI (i.e., CII-BPI-1, CII-BPI-2, and CII-BPI-3; Table 1) and evaluated their efficacy in suppressing collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) in a mouse model. These molecules are composed of antigenic peptides from collagen II (i.e., CII256-270, CII707-721, and CII11237-1249) linked via a spacer to a cell adhesion peptide called LABL. The LABL peptide is derived from the I-domain of αL-integrin (CD11a237-246), which binds to ICAM-1. At the molecular level, these molecules may block the formation of the immunological synapse necessary for T-cell activation [28]. The efficacies of CII-BPI molecules to suppress the progress of RA were compared to those of the respective parent antigenic peptides from CII in the CIA mouse model. The effect of CII-BPI molecules in altering cytokine production was also determined.

Table 1.

Peptide Sequences

| CII Sequence Source | Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| CII707-721 | CII-1 | PPGANGNPGPAGPPG |

| CII707-721 | CII-BPI-1 | Ac-PPGANGNPGPAGPPG-(AcpGAcpGAcp)2-ITDGEATDSG-NH2 |

| CII256-270 | CII-2 | Ac-GEPGIAGFKGEQGPK-NH2 |

| CII256-270 | CII-BPI-2 | Ac-GEPGIAGFKGEQGPK-(AcpGAcpGAcp)2-ITDGEATDSG-NH2 |

| CII1237-1249 | CII-3 | Ac-QYMRADEADSTLR-NH2 |

| CII1237-1249 | CII-BPI-3 | Ac-QYMRADEADSTLR-(AcpGAcpGAcp)2-ITDGEATDSG-NH2 |

Ac: Acetyl group; Acp: ε-aminocaproic acid; G: Glycine

Materials and Methods

Animals

The DBA/1J male mice utilized in study-I and -II were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For study-III, DBA1BOM male mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility at The University of Kansas approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All experimental procedures using live mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Kansas.

Peptide Synthesis

Peptides used in this study (Table 1) were synthesized using a solid phase peptide synthesizer (Pioneer; Perceptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) on a polyethylene glycol-polystyrene resin (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl-protected amino acid chemistry. Cleavage of the peptides from the resin and removal of the protecting groups were carried out using trifluoroacetic acid in the presence of scavengers. Reversed-phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) using a C18 column was employed to purify the crude peptide using a gradient of solvent A (95% H2O with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and 5% acetonitrile) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile). The pure peptide was analyzed by analytical HPLC using an analytical C18 column and the identity of the peptide was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.

Induction of CIA and Therapeutic Study

For study-I and -II, bovine type II collagen (CII, Elastin Products, Owensville, MO) was dissolved in 0.05 M acetic acid overnight at 4°C at a concentration of 6 mg/ml. CFA was prepared by addition of killed mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (Difco, Detroit, MI) to IFA (Difco) at a concentration of 8 mg/ml. The solution of CII (6 mg/ml) was emulsified in an equal volume of CFA. Six-to-eight-week-old DBA/1J mice were immunized with 100 μl of emulsion containing 300 μg CII and 400 μg mycobacteria injected intradermally at the tail base. After 21 days, all mice received a booster dose of 100 μl of emulsion containing 300 μg CII injected intradermally at the tail base.

For study-I, the mice received intravenous (i.v.) injections of CIIBPI-1 and CII-1 peptides (100 nmol/injection) on days 19, 22, and 25. In another group, mice were injected with 5 mg/kg in 100 μl of MTX-cIBR for 10 days from day 19. For study-II, the same disease induction protocol was followed, with the mice receiving i.v. injections of CIIBPI-2, CII-BPI-3, CII-2, and CII-3 (100 nmol/injection) on days 19, 22, and 25. For study-III, a readily available chicken collagen/CFA emulsion, containing 1.0 mg/ml of type II chicken collagen and 2.0 mg/ml of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Hooke Laboratories, Lawrence, MA), was injected intradermally. This was followed by an intradermal IFA emulsion injection, containing 1 mg/ml of chicken type-II collagen, on day 21. The mice were given i.v. injections of peptides (100 nmol/injection) on days 17, 22, 25, and 28. Disease progression was evaluated by measuring the increase in paw swelling of the fore limbs as well as hind limbs. Paw volume was determined by measuring the volume of water displaced by the paw before and after disease induction. Paw volume determined prior to disease induction was used as the baseline. Percent increase in paw volume, ΔVpaw, was calculated using the equation below:

Histopathology of the Joints

Development of CIA in DBA/1J mice was also assessed histologically. In study-II, both hind limbs were removed 30 days after the second immunization and fixed in formalin prior to analysis. Arthritic changes and joint damage were individually scored for articular cartilage damage, pannus formation, synovial membrane thickening, synovial capsule thickening, and inflammatory cell infiltrate. The score was totaled as: 0, no lesions; 1, mild changes; 2, moderate changes; 3 and 4, severe changes. The histopathology evaluation was done by Dr. Stan Kosanke at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

Determination of Cytokine Levels in Serum in DBA1BO-M mice In Vivo

To understand the mechanism of action of CII-BPI in inhibiting the progression of CIA, cytokine levels in serum obtained from treated and untreated mice were measured. First, we wanted to look at the effect of peptide treatment in the production of IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine on day 31 immediately following treatment and on day 44 at the end of the study. Second, we looked at the effect of dose on IL-6 serum levels following three and four injections of peptide. Third, we also looked at other different cytokines present in serum of treated and untreated mice. Cytokine production was measured by obtaining blood samples on indicated days from the study-III group without sacrificing the mice. Blood samples were allowed to clot overnight at 4°C before centrifuging at 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes the next day. Serum was collected and stored at -80°C until analysis. Serum cytokine analysis was performed using a fully quantitative ELISA-based Q-Plex™ Mouse Cytokine-Screen (Quansys Biosciences, Logan, UT).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences among the groups in volume displacement, histopathological score, and serum cytokine levels were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's least significant difference. All analyses were performed using StatView (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Suppression of CIA by CII-BPI

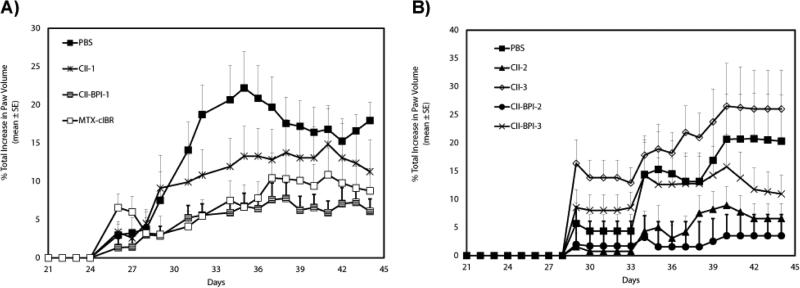

In study-I, the animals (DBA/1J male mice) injected with bovine collagen in CFA developed signs of rheumatoid arthritis approximately four days after administration of the booster dose on day 21; these signs included inflammation of their limbs as well as joint damage (Figure 1A). Changes in paw volume due to swelling were significantly lower in CII-BPI-1-treated mice than in those treated with PBS (Figure 1A; p<0.01 from days 40 to 44). Also, CII-1 peptide-treated mice had significant suppression of arthritis compared to the PBS-treated control group (p<0.01 from days 40 to 44). CIIBPI-1 peptide had better CIA suppressive activity than CII-1 peptide (Figure 1A; p<0.01, through days 40-44), suggesting that forming BPI-type molecules improves the biological activity of the peptide. The positive control treatment, MTX-cIBR (5 mg/kg), suppressed arthritis better than PBS (p<0.01, through days 40-44) and with almost the same potency as the CII-BPI-1 peptide (p>0.10). MTX-cIBR has been shown to be effective in suppressing arthritis in adjuvant arthritis rats [29].

Figure 1.

In vivo efficacy of CII-BPIs and their respective antigenic peptides in suppressing collagen-induced arthritis in CIA mouse model. PBS and MTX-cIBR were used as negative and positive controls. DBA/1J mice were immunized intradermally at the tail base with CII/CFA on day 0 and followed by a booster dose at day 21 as described in Material and Methods section. Intravenous injections of peptides (100 nmol/ injection) were administered on days 19, 22, and 25. For the MTX-cIBR group, mice were injected with 5 mg/kg in 100 uL of MTX-cIBR for 10 days beginning at day 19. The changes in paw volume were measured daily. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error (n=7– 9). A, Study I shows evaluation of CII-BPI-1, CII-1, and MTX-cIBR. B, Study II shows efficacies of CII-BPI-2, CII-BPI-3, CII-2, and CII-3. Statistical values conducted on days 40-44 for changes in paw volume compared with PBS were as follows: CII-BPI-1, p<0.01; CII-1, p<0.01; CII-BPI-2, p<0.0001; CII-BPI-3, p<0.05; and CII-2, p<0.001.

In study-II, the efficacies of CII-BPI-2 and CII-BPI-3 were compared to those of their respective antigenic peptides, CII-2 and CII-3, in suppressing CIA using DBA/1J male mice (Figure 1B). Study II was carried out using the same protocol as illustrated in study I. Bovine type II collagen was used to induce CIA in male DBA1/J mice. After disease induction these animals were treated with three injections of the peptides. Suppression of inflammation was monitored by measuring changes in paw volume and histopathology analysis of the limbs on day 30. Our results showed that both CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 had significantly (p<0.001) lower paw swelling compared to PBS (Figure 1B); suggesting that these two peptides had some activity in suppressing inflammation of the limbs. We did not see any statistical significance (p>0.05) between CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 peptides. However our data showed that CII-BPI-2 had a moderately stronger suppression of inflammation than CII-2 as illustrated by changes in paw volume (Figure 1B). It is clear that CII-BPI-2 has better efficacy than CII-BPI-3 and CII-3 peptide (p<0.05, through days 40-44). In contrast to other peptides, there is a trend that CII-3-treated mice had a higher paw volume compared to those treated with PBS; suggesting that CII-3 exacerbated the disease.

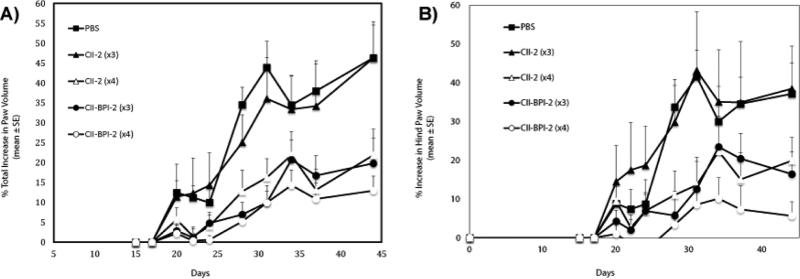

In contrast to our studies with other models of autoimmune disease for example EAE mouse models, we observed that although we were able to induce CIA in male DBA1/J mice using bovine type II collagen we had a high variability in disease induction as well as severity of the disease. This could be one of the contributing factors that made it difficult for us to clearly make a distinction between the activities of these peptides. To improve on the reproducibility of our investigations, we switched to using chicken type II collagen for disease induction. Others have shown that disease induction using chicken type II collagen had a higher incidence and disease severity compared to other native type II collagen [30]. We also used male DBA1BO-M mice instead of male DBA1/J mice that were used in study I and II. Thus in study-III, DBA1BO-M male mice were used, and the disease was stimulated using chicken collagen in CFA. DBA1BO-M mice developed more severe clinical arthritis than did the DBA/1J mice utilized in study-I and -II. According to the percent changes in paw swelling of all four limbs (Figure 2A), it is clear that 4 injections of CII-2 were significantly more effective than 3 injections of CII-2 (p<0.001, through days 34-44). Although 4 injections of CIIBPI-2 were better than 3 injections, it was difficult to differentiate the efficacies of 3 and 4 injections of CII-BPI-2 peptide. In some instances such as evaluation of the hind limbs (Figure 2B), there was a similar trend showing that 4 injections of CII-BPI-2 were more effective than either 3 injections of CII-BPI-2 but the data did not show any significant difference. However, 3 injections of CII-BPI-2 was significantly better than 3 injections of CII-2 peptide (p<0.001, through days 34-44), suggesting that CII-BPI-2 is more potent than CII-2 peptide. In this animal model, three injections of CII-2 peptide did not show any efficacy in suppressing the changes in paw volume. These results indicate that CII-BPI-2 is more potent than CII-2 peptide and that the activity of these peptides is dose-dependent.

Figure 2.

In vivo activity of the CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 peptides in suppressing collagen-induced arthritis in the mouse model after varying injections. In study-III, DBA1BO male mice were immunized with CII/CFA intradermally and given a booster dose on day 21 as described in Materials and Methods. The mice were then given three i.v. injections of peptides (100 nmol/injection) on days 17, 22, and 25 or four injections on days 17, 22, 25, and 28. The disease progression was observed by monitoring the changes in the volume of (A) all four paws or (B) just the hind paws. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error (n=7–9). Statistical values showed that three or four injections of CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 were significantly better than PBS (p<0.0001, days 34-44). Four injections of CII-2 were more effective compared to three injections (p<0.001, days 34-44). Three injections of CII-BPI-2 were better than three injections of CII-2 (p<0.001, days 34-44). Data from all four limbs as well as hind limbs alone showed that there was a trend indicating that four injections of CII-BPI-2 were better than three injections.

Histopathological Analysis

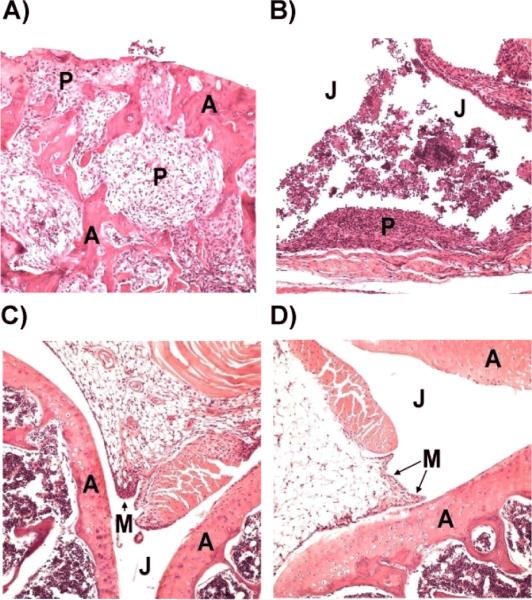

To evaluate the effect of CII-BPI molecules in suppressing CIA, the histopathology of the joints of the animals was examined for cartilage erosion and cell infiltration in the joint space. For the untreated arthritic mice, the knee joints had moderate evidence of articular cartilage damage with pannus formation (Figure 3A). The synovial membrane and capsule were both markedly thickened as a result of pannus formation and inflammatory cell infiltration. The synovial linings were hyperplastic with sloughing of synoviocytes into the joint space. The inflammatory cellular infiltrate consisted of a mixture of mostly synovial macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphoplasmacytic cells. In the untreated group, the chronic inflammation destroyed the joint lining, including the cartilage and other nearby supporting structures, such as bone (Figure 3B). The formation of pannus is a result of overgrowth of the synoviocytes and the observed accumulation of inflammatory cells that led to deformed cartilage and bone, which agrees with the observed clinical scores.

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of knee joints in peptide- and PBS-treated mice. A & B, Images of the joints of PBS-treated mice with articular cartilage damage as well as a collection of cellular exudates within the joint spaces. C, Image of mouse joint treated with CII peptide, which appears essentially normal. D, Image of the joint of a mouse treated with CII-BPI-2 showing minimal inflammation. J: Joint space; M: Synovial membrane; P: Pannus formation; A: Articular cartilage.

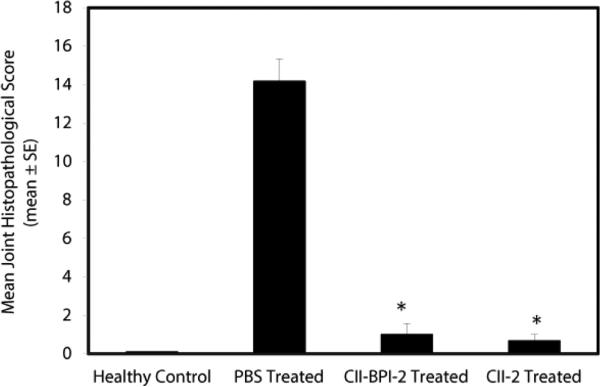

For mice treated with CII-2 peptide, four out of six knee joints appeared normal (Figure 3C), and the two remaining joints had very mild evidence of synovial membrane thickening with pannus formation, which falls within normal limits. Minimal evidence of chronic inflammation and articular cartilage damage were observed in the mice group treated with CII-BPI-2 (Figure 3D). Two of the six knee joints from the mice treated with CII-BPI-2 had very mild evidence of synovial membrane thickening. Mice treated with CII-2 and CII-BPI had a lower incidence of inflammation and cell infiltration into the joint space as well as cartilage damage. Overall, mice treated with CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 peptides had significantly lower joint histopathological scores than the PBS-treated group (p<0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the mean scores of joint histopathology of normal untreated mice and diseased mice treated with PBS, CIIBPI-2, and CII-2 peptides in the mouse CIA model. CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 had significantly (p<0.0001) lower scores compared with PBS.

The CII-treated and CII-BPI-2-treated mice had significantly lower cartilage erosion and inflammatory infiltrates in the joint space compared to those treated with PBS. Although we did not see any significant difference in the histopathological analysis of the joint limbs in mice treated with CII-BPI-2 and CII-2, the results showed that CII-BPI-2 had a slightly stronger effect in amelioration erosion and infiltration of the joints. As mentioned above, one of the reasons why we could make a distinction between CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 was because of the high variability in disease incidence and severity. We observed that using bovine type II collagen to induce CIA in male DBA1/J mice gave a high variability in disease incidence and severity. Also, the dose is important. At a lower dose, we could distinguish the activities of the two peptides in suppressing CIA in male DBA1BO-M mice but we did not see any significant difference when we increased the dose or frequency of administration.

Cytokine Serum Levels in DBA1BO-M Mice In Vivo

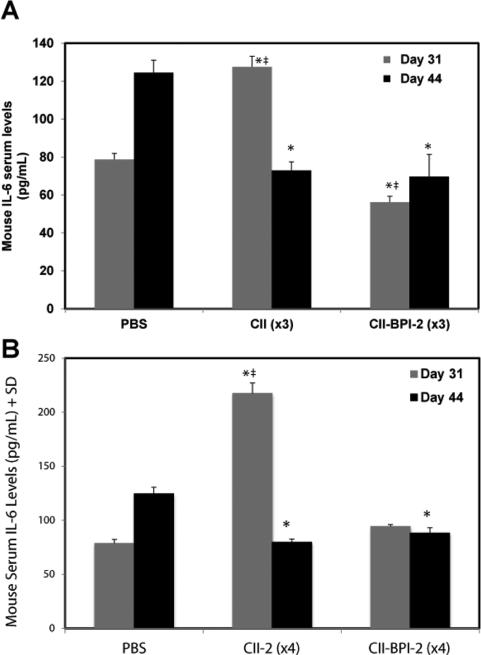

To determine the effect of the CII-BPI treatment in study-III on cytokine levels, the levels of different cytokines in the serum were determined using ELISA on day 31 at around the disease peak and on day 44 when the arthritis swelling was at the plateau region. On day 31, the IL-6 levels were significantly lower in mice injected 3 times with CII-BPI-2 than in those treated with PBS (p<0.0001) and CII-2 (p<0.0001) (Figure 5A). However, the CII-2-treated group had higher serum IL-6 levels than the PBS group (p<0.0001). Once the arthritic swelling reached a plateau on day 44 (Figure 5A), the serum IL-6 concentration of the CII-2 group significantly decreased compared to that of the PBS-treated group (p<0.0001). During periods of disease remission, there was no significant difference was observed in IL-6 levels between CII-2- and CII-BPI-2-treated mice. These results suggest that although CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 were efficacious in suppressing CIA, IL-6 serum levels indicate that may have different mechanisms of suppressing arthritis.

Figure 5.

The serum cytokine levels of IL-6 of mice treated with PBS, CII-2, and CII-BPI-2 on days 31 and 44. A, Mice treated with three injections of CII-BPI-2 have significantly lower levels of IL-6 in the serum than those injected with PBS (*, p<0.0001) and three injections of CII-2 (#, p<0.0001). Serum IL-6 levels are significantly higher on day 31 in the mice treated with CII-2 than in PBS-treated mice (‡, p<0.0001). Serum levels of the cytokine IL-6 are significantly lower on day 44 after three injections of CII-2 (*, p<0.0001) and CII-BPI-2 (*, p<0.0001) compared to PBS. A significant difference between IL-6 levels of CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 on day 44 was not observed. B, Comparison of serum IL-6 levels of mice treated with four injections of PBS, CII-2, and CII-BPI-2 on days 31 and 44. Serum IL-6 levels are significantly higher in the CII-2 group compared to the PBS group (‡, p<0.0001) and CIIBPI-2 (*, p<0.0001). Significant differences between IL-6 levels of CII-BPI-2 and PBS were not observed. On day 44, serum IL-6 levels were significantly higher in the PBS-treated group compared to the CII-2 (*, p<0.0001) and CII-BPI-2 groups (*, p<0.0001). No significant difference in IL-6 levels was observed between CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 treated groups on day 44.

In the groups injected four times with treatment peptides, the serum level of IL-6 in the CII-2 group was nearly three times higher than that seen in the PBS-treated group at the peak of the disease on day 31 (p<0.0001)(Figure 5B). No significant difference between IL-6 concentrations of CII-BPI-2 and PBS was observed on day 31. Analysis of the mouse cytokine levels at the end of the study (day 44) showed that IL-6 levels were lower in both the CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 groups when compared to the PBS group (p<0.0001). As with day 31, the results of the IL-6 levels obtained from mouse serum on day 44 suggest that tethering an adhesion molecule to the antigenic peptide in CIIBPI-2 may produce a different mechanism of action than that of CII-2 peptide. It is difficult to suggest that similar IL-6 levels in CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 on day 44 imply that the two peptides had similar activity. There is a possibility that on day 44, the disease was entering a remission phase as shown by paw swelling essentially reaching a plateau and there is less inflammation at that point. Thus, like most autoimmune diseases, there is more intense inflammation prevalent during the initial phase but reduced inflammatory activity during the secondary and progressive phase [31]. It is plausible that during remission the effect of the two peptides on IL-6 production is essentially over and what we were observing is just the clearance phase of IL-6 from systemic circulation on day 44. Thus, we would anticipate significantly lower IL-6 levels in the two treatment groups.

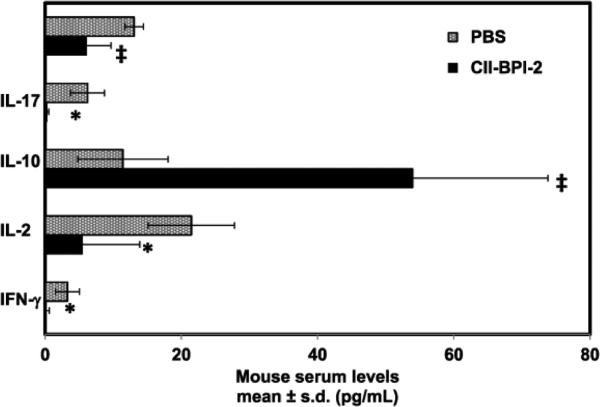

Additional cytokines evaluated in serum of CII-BPI-2 and control provided a better insight into the mechanism of action. Our studies showed that CII-BPI-2 had significantly lower (p<0.01) pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-17, and TNF-α) compared to the control (Figure 6). On the other hand, we observed significantly higher (p<0.001) levels of IL-10 in CII-BPI-2 treated mice compared to the control group. All these findings suggest that CII-BPI-2 had a suppressive effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines while promoting the production of cytokines associated with regulatory T cell phenotypes.

Figure 6.

The serum pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels of mice treated with PBS and CII-BPI-2 on day 31. Mice treated with three injections of CII-BPI-2 have significantly lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-17, and TNF-α) in serum than those injected with PBS (*, p<0.01 and ‡, p<0.001). Furthermore, serum IL-10 levels were significantly higher (p<0.001) in CII-BPI-2 groups compared to the control group.

Discussion

Auto-reactive T cells have been implicated in the onset and progression of autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS), type-1 diabetes (T1D), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These auto-reactive T cells have been shown to be activated via the formation of an “immunological synapse” at the interface between the T cells and APC [32-34]. Differentiation of naïve T cells to auto-reactive T cells is strongly dependent on the type of the co-stimulatory signal involved in the formation of the immunological synapse. A vast number of studies have demonstrated that administration of soluble antigenic peptides can induce immune tolerance [35-37]. It is thought that soluble antigenic peptides bind to empty MHC-II on the surface of immature dendritic cells and, in the absence of a co-stimulatory signal, cause the naïve T cells to differentiate into T-regs [35].

The extracellular matrix of cartilage consists mainly of type II (CII) collagen. CII, like myelin basic protein, can elicit tissue-specific autoimmune disease [38-40]. Some collagen derived peptides (e.g., CII256-270, CII707-721, and CII1237-1249) have been used induce immunotolerance and have been shown to hinder the progression of CIA [41,42]. The selection of CII peptides used in this the present study was based on previous studies showing that certain epitopes such as CII256-270 can bind to I-Aq MHC class II molecules [40,43]. Experiments with CII256-270 have also shown that this peptide sequence can inhibit the progression of CIA [40,44]. It has been suggested that CII260-267 is the immunodominant core [40,44]. Another major immunodominant epitope (CII707-721, CII-1) that we studied has previously been found to elicit a significant proliferative T-cell response [41]. This peptide contains a combination of two overlapping core sequences of CII704-712 and CII710-718 [41]. CII707-721 acetylated at the N-terminus and amidated at the C-terminus has also been shown to strongly induce proliferation and that IFN-γ release correlates well with the proliferative responses induced by CII707-721 [41]. CII1237-1249 or CII-3 peptide was selected based on its ability to selectively bind to the RA-associated DR4 MHC molecule [45-47]. Because CII1237-1249 and CII707-721 have not been studied as extensively as CII256-270, their potential mechanisms have not been well elucidated. The susceptibility of mice to CIA is confined mostly to MHC type I-Aq [43].

The potential of antigenic peptides use in the treatment of autoimmune diseases can be improved via use of bifunctional peptide inhibitors (BPI). Here, we can expect that the CII-BPI peptide will selectively block the activation of a subpopulation of T cells that recognizes the collagen peptide-MHC-II complex without eliminating the ability of the host to activate subpopulations of T cells that could fight pathogenic infections. The hypothesis is that BPI molecules target and bind to the molecular components of the immunological synapse; thus, inhibiting formation of the immunological synapse at the interface of T cell and antigen-presenting cell [28,48]. Co-capping experiments with GAD-BPI showed that I-Ag7 and ICAM-1 receptors were highly co-localized on the surface of GAD-BPI-treated APC compared to APC treated with a mixture of unlinked peptides (GAD208-217 and LABL) [28]. Also, binding of GAD-BPI to APC was blocked by either anti-I-Ag7 or anti-ICAM-1 mAbs [28]; indicating that BPI molecules can tether the two signals thus preventing their translocation and eventual maturation of the immunological synapse. In vivo efficacy results showed that PLP-BPI and GAD-BPI molecules were effective in the suppression of EAE [26,27,49] and T1D, respectively, in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice [28]. Furthermore, studies with PLP-BPI showed that PLP-BPI was more effective in disease suppression compared to the antigenic peptide alone (i.e., PLP139-151), CD11a237-246 peptide alone (i.e., LABL), unlinked mixture of PLP139-151 and LABL, or other control peptides [49]. Because BPI molecules were more effective than the parent antigenic peptides alone in suppressing autoimmune disease in animal models, this suggests that the cell adhesion peptide (i.e., LABL portion) in BPI as well as BPI structure has an important role in the in vivo activities of BPI molecules. Results from this study showed that BPI molecules (e.g., CII-BPI-1 and CII-BPI-2) formed by conjugating antigenic peptides derived from collagen to adhesion peptides have greater efficacies in suppressing arthritis in CIA mice than their respective parent antigenic peptides (CII-1 and CII-2). It was also found that neither CII-BPI-3 nor CII-3 peptides were effective in preventing the progress of arthritis, suggesting that the sequence of the antigen was not appropriate for inducing tolerance in this model.

Our previous work with PLP-BPI in EAE mouse model showed that PLP-BPI-treatment increased TGF-β and IL-10 production, suggesting the involvement of T-reg [28]. Also, both PLP-BPI and GAD-BPI enhanced the production of IL-4, indicating the involvement of Th2 differentiation and proliferation. Furthermore, the PLP-BPI-treated animals had lower IL-17 than those treated with PBS, indicating the suppression of Th17 proliferation [27]. Researchers have recently confirmed the importance of the IL-17-producing Th17 cells in CIA. In two separate experiments, the absence of Th17 lymphocytes in mice deficient in IL-17 and the administration of anti-IL-17 antibodies have been shown to significantly reduce the severity of CIA [50,51]. Others have also shown that IL-17-deficient mice could markedly suppress CIA by curbing the activation of autoantigen-specific T cells and B cells in the sensitization phase of CIA. Similarly, altered peptide ligand (APL) molecules from collagen II have been shown to suppress arthritis by the expansion of T-reg and lowering of Th1 and Th17 [52,53]. IL-17 has been reported to activate osteoclasts and induce the production of various cytokines by macrophages, monocytes, and synoviocytes (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, and TNF-α) [11,54,55].

Cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-21 have been implicated in the induction of Th17 [55-57]. IL-6 has been shown to induce Th17 differentiation in both humans and mice. A study by Kelchtermans et al. showed that a transfer of T-regs not only significantly improves CIA but also lowers TNF-α and IL-6 levels in mouse sera [11]. The decreased levels of mouse IL-6 cytokine in mouse sera that we observed would suggest that CII-2 and CII-BPI-2 might possibly suppress CIA by regulating the immune cells responsible for arthritis [8]. In the EAE mouse model, it was also shown that a deficiency of IL-6 shifted the immune response away from an immunogenic role to a protective one [58]. Our results suggest that CII-BPI-2 could possibly be altering the differentiation of naïve T cells into T-regs while suppressing pro-inflammatory T cells.

It is interesting to note that even though CII-2 (i.e., CII256-270) antigenic peptide eventually lowers IL-6 levels, these levels were still found to be significantly higher during the peak of the disease in CII-2-treated mice than in the control group. Mice injected three times with CII-BPI-2 (i.e., CII256-270-BPI) showed significantly lower levels of the inflammatory IL-6 cytokines on day 31 than did either CII-2- or PBS-treated mice. In contrast, four injections of CII-BPI-2 did not produce any significant difference between the CII-BPI-2- and PBS-treated mice. Given that four injections of either CII-BPI-2 or CII-2 were effective in the suppression of CIA as demonstrated by the clinical paw data, it is plausible that injection of soluble antigenic peptide resulted in a transient increase in IL-6 levels. CII-BPI-2 has an antigenic peptide component in it, and more injections led to a slight increase in IL-6 levels. However, CII-BPI-2 did suppress induction of IL-6; thus, the increase in IL-6 levels was not as high as in CII-2-treated mice. This could also suggest that CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 have entirely different mechanisms of action. These observations were consistent with our findings with other BPI molecules. Even though PLP-BPI was effective in suppressing EAE, its administration resulted in an initial increase in IL-17 levels [26]. However, analysis of IL-6 levels in serum on day 44 showed that CII-BPI-2- and CII-2-treated mice had significantly lower IL-6 levels compared to the control group. All of these taken together indicate that CII-BPI-2 and CII-2 suppress disease by decreasing IL-6 response; this can, in turn, suppress the downstream Th17 proliferation and perhaps enable a shift in the balance toward T-regs proliferation. Also, decreasing the serum levels of IL-6 inhibits osteoclastogenesis [11]. In arthritis, osteoclasts are present in the inflamed synovium and contribute greatly to the destruction of bone. Histopathology of the mice treated with CII-BPI-2 confirmed the absence of osteoclasts.

In conclusion, CII-BPI-1 and CII-BPI-2 can suppress CIA more effectively than their parent compounds. Tethering of the LABL adhesion peptide to the CII peptide seems to better suppress CIA by shifting the immune balance from a pro-inflammatory to a regulatory response. Future studies will aim to better elucidate the mechanism of the BPI peptide by studying other cytokine markers both in sera and in splenocytes. Furthermore, optimization of the dose and dosing schedule and utilization of a different route of delivery may lead to better suppression of CIA.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI-063002 and R56-AI-063002) and Institute for Advancing Medical Innovation (The University of Kansas Cancer Center) for supporting this work. BB was also supported by a Pharmaceutical Aspects of Biotechnology Training Grant (NIGMS, T32-GM008359). We are grateful for the help of Nancy Harmony in proofreading the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to the design, performing laboratory investigations, analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- LFA-1

Leukocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1

- MHC-II

Major Histocompatibility Complex-II

- ICAM-1

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1

- APC

Antigen-Presenting Cells

- TNF

Tumor Necrosis Factor

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- Th

T-helper

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Steiner G. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:473–488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joosten LA, Helsen MM, van de Loo FA, van den Berg WB. Anticytokine treatment of established type II collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1 mice. A comparative study using anti-TNF alpha, anti-IL-1 alpha/beta, and IL-1Ra. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:797–809. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindstrom TM, Robinson WH. Rheumatoid arthritis: a role for immunosenescence? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1565–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RO. Collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Methods Mol Med. 2007;136:191–199. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-402-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto S, Sugahara S, Ikeda K, Shimizu Y. Amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis in mice by a novel phosphodiesterase 7 and 4 dual inhibitor, YM-393059. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;559:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nandakumar KS, Holmdahl R. Antibody-induced arthritis: disease mechanisms and genes involved at the effector phase of arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:223. doi: 10.1186/ar2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Romagnani S. Human and murine Th17. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:114–119. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833647c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assier E, Boissier MC, Dayer JM. Interleukin-6: from identification of the cytokine to development of targeted treatments. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Cancedda R, Pennesi G. Cell therapy using allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents tissue damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1175–1186. doi: 10.1002/art.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huan J, Kaler LJ, Mooney JL, Subramanian S, Hopke C, et al. MHC class II derived recombinant T cell receptor ligands protect DBA/1 LacJ mice from collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;180:1249–1257. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelchtermans H, Geboes L, Mitera T, Huskens D, Leclercq G, et al. Activated CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells inhibit osteoclastogenesis and collagen-induced arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:744–750. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.086066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakatsukasa H, Tsukimoto M, Tokunaga A, Kojima S. Repeated gamma irradiation attenuates collagen-induced arthritis via up-regulation of regulatory T cells but not by damaging lymphocytes directly. Radiat Res. 2010;174:313–324. doi: 10.1667/RR2121.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010;376:1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huizinga TW, Pincus T. In the clinic. Rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-01001. ITC1-1-ITC1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soubrier M, Mathieu S, Payet S, Dubost JJ, Ristori JM. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ede AE, Laan RF, Blom HJ, De Abreu RA, van de Putte LB. Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: an update with focus on mechanisms involved in toxicity. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;27:277–292. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracey D, Klareskog L, Sasso EH, Salfeld JG, Tak PP. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanisms of action: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:244–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer J, Ritchlin C, Mendelsohn A, Baker D, Kim L, et al. Golimumab, a new human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody, administered intravenously in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: Forty-eight-week efficacy and safety results of a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010;62:917–928. doi: 10.1002/art.27348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubbert-Roth A, Finckh A. Treatment options in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing initial TNF inhibitor therapy: a critical review. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/ar2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zidi I, Bouaziz A, Mnif W, Bartegi A, Al-Hizab FA, et al. Golimumab therapy of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pescovitz MD. Rituximab, an anti-cd20 monoclonal antibody: history and mechanism of action. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mok CC. Rituximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an update. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;8:87–100. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S41645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badawi AH, Siahaan TJ. Suppression of MOG- and PLP-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis using a novel multivalent bifunctional peptide inhibitor. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;263:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiptoo P, Buyuktimkin B, Badawi AH, Stewart J, Ridwan R, et al. Controlling immune response and demyelination using highly potent bifunctional peptide inhibitors in the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172:23–36. doi: 10.1111/cei.12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badawi AH, Kiptoo P, Wang WT, Choi IY, Lee P, et al. Suppression of EAE and prevention of blood-brain barrier breakdown after vaccination with novel bifunctional peptide inhibitor. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1874–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridwan R, Kiptoo P, Kobayashi N, Weir S, Hughes M, et al. Antigen-specific suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by a novel bifunctional peptide inhibitor: structure optimization and pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:1136–1145. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi N, Kiptoo P, Kobayashi H, Ridwan R, Brocke S, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by a novel bifunctional peptide inhibitor. Clin Immunol. 2008;129:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray JS, Oney S, Page JE, Kratochvil-Stava A, Hu Y, et al. Suppression of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice by bifunctional peptide inhibitor: modulation of the immunological synapse formation. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;70:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumdar S, Anderson ME, Xu CR, Yakovleva TV, Gu LC, et al. Methotrexate (MTX)-cIBR conjugate for targeting MTX to leukocytes: conjugate stability and in vivo efficacy in suppressing rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:3275–3291. doi: 10.1002/jps.23164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmdahl R, Jansson L, Gullberg D, Rubin K, Forsberg PO, et al. Incidence of arthritis and autoreactivity of anti-collagen antibodies after immunization of DBA/1 mice with heterologous and autologous collagen II. Clin Exp Immunol. 1985;62:639–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piehl F. A changing treatment landscape for multiple sclerosis: challenges and opportunities. J Intern Med. 2014;275:364–381. doi: 10.1111/joim.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, et al. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philipsen L, Engels T, Schilling K, Gurbiel S, Fischer KD, et al. Multimolecular analysis of stable immunological synapses reveals sustained recruitment and sequential assembly of signaling clusters. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2551–2567. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.025205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tseng SY, Dustin ML. T-cell activation: a multidimensional signaling network. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larché M, Wraith DC. Peptide-based therapeutic vaccines for allergic and autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2005;11:S69–76. doi: 10.1038/nm1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Krasovsky J, Munz C, Bhardwaj N. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:233–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santambrogio L, Sato AK, Fischer FR, Dorf ME, Stern LJ. Abundant empty class II MHC molecules on the surface of immature dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15050–15055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corthay A, Bäcklund J, Holmdahl R. Role of glycopeptide-specific T cells in collagen-induced arthritis: an example how post-translational modification of proteins may be involved in autoimmune disease. Ann Med. 2001;33:456–465. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dzhambazov B, Nandakumar KS, Kihlberg J, Fugger L, Holmdahl R, et al. Therapeutic vaccination of active arthritis with a glycosylated collagen type II peptide in complex with MHC class II molecules. J Immunol. 2006;176:1525–1533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myers LK, Sakurai Y, Tang B, He X, Rosloniec EF, et al. Peptide-induced suppression of collagen-induced arthritis in HLA-DR1 transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3369–3377. doi: 10.1002/art.10687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bayrak S, Holmdahl R, Travers P, Lauster R, Hesse M, et al. T cell response of I-Aq mice to self type II collagen: meshing of the binding motif of the I-Aq molecule with repetitive sequences results in autoreactivity to multiple epitopes. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1687–1699. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayrak S, Mitchison NA. Bystander suppression of murine collagen-induced arthritis by long-term nasal administration of a self type II collagen peptide. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:92–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang JC, Vestberg M, Minguela A, Holmdahl R, Ward ES. Analysis of autoreactive T cells associated with murine collagen-induced arthritis using peptide-MHC multimers. Int Immunol. 2004;16:283–293. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holm L, Kjellén P, Holmdahl R, Kihlberg J. Identification of the minimal glycopeptide core recognized by T cells in a model for rheumatoid arthritis. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dessen A, Lawrence CM, Cupo S, Zaller DM, Wiley DC. X-ray crystal structure of HLA-DR4 (DRA*010, DRB1*0401) complexed with a peptide from human collagen II. Immunity. 1997;7:473–481. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammer J, Gallazzi F, Bono E, Karr RW, Guenot J, et al. Peptide binding specificity of HLA-DR4 molecules: correlation with rheumatoid arthritis association. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1847–1855. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metsäranta M, Toman D, de Crombrugghe B, Vuorio E. Mouse type II collagen gene. Complete nucleotide sequence, exon structure, and alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16862–16869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yusuf-Makagiansar H, Yakovleva TV, Tejo BA, Jones K, Hu Y, et al. Sequence recognition of alpha-LFA-1-derived peptides by ICAM-1 cell receptors: inhibitors of T-cell adhesion. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;70:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi N, Kobayashi H, Gu L, Malefyt T, Siahaan TJ. Antigen-specific suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by a novel bifunctional peptide inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:879–886. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lubberts E. IL-17/Th17 targeting: on the road to prevent chronic destructive arthritis? Cytokine. 2008;41:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lubberts E, van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, Schwarzenberger P, Coenen-de Roo CJ, et al. IL-17 promotes bone erosion in murine collagen-induced arthritis through loss of the receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin balance. J Immunol. 2003;170:2655–2662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakamatsu E, Matsumoto I, Yoshiga Y, Hayashi T, Goto D, et al. Altered peptide ligands regulate type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:366–371. doi: 10.1007/s10165-009-0174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao J, Li R, He J, Shi J, Long L, et al. Mucosal administration of an altered CII263-272 peptide inhibits collagen-induced arthritis by suppression of Th1/Th17 cells and expansion of regulatory T cells. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0634-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int Immunol. 2009;21:489–498. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hirahara K, Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Kanno Y, et al. Signal transduction pathways and transcriptional regulation in Th17 cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chitnis T, Khoury SJ. Cytokine shifts and tolerance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunol Res. 2003;28:223–239. doi: 10.1385/IR:28:3:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]