Cancer clinical trials have been the catalyst for many practice changing clinical advances in oncology [1, 2]. Increasingly, however, there is a realization that (a) the traditional drug discovery/drug development model is unsustainable [3]; (b) adult participation in cancer clinical trials is underwhelming, with recruitment rates sometimes as low as 5% [4]; and (c) in the era of targeted therapies, the classic drug A versus drug B strategy may no longer be fit for purpose [5], in many cases producing little or no incremental benefit when transformative improvement is what our patients need. Recognizing the limits of this traditional two arm approach (which frequently fails to demonstrate superiority after many years of effort [3]), Parmar et al. [6] have recently argued for a cultural shift in clinical trial methodology toward a multiarm design that can answer several clinical questions in the same time frame. We submit that this thesis also has important implications for biomarker-stratified clinical trials, in which evaluation of multiple novel therapies is often required, underpinned by precise biomarker-guided patient selection.

In metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), a more granular understanding of disease biology has fueled the development of a number of gene or pathway-targeted therapeutic approaches, increasing the armamentarium of drugs at our disposal to treat this aggressive malignancy. However, the design of clinical trials that incorporate these novel drugs in their appropriate genetic context is crucial. Recognizing and responding to this challenge, we propose a change in the clinical trial paradigm, eschewing the increasingly limited two-arm approach in favor of a more progressive multistage protocol that integrates one or more treatment comparisons against controls in each of several biomarker-selected subgroups within a single trial program. FOCUS4 is a population-enriched biomarker-stratified clinical trial program for first-line treatment of mCRC [7], designed to allow the efficacy and safety of multiple novel therapies to be assessed rapidly and efficiently in a single protocol, while also evaluating the effectiveness of a biomarker-guided stratified approach.

FOCUS4 is a single trial design, in which each biomarker cohort is evaluated through a phase II/III enrichment approach. Putative biomarkers have already been identified for each treatment arm. In our initial staged analysis, the principle is that we first identify a positive effect, which then informs evaluation of both biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative patient groups. This enrichment approach allows refinement of the biomarker strategy as the program evolves—codevelopment of the companion diagnostic(s) and the different treatment arms is an important capability that is specifically built into our overarching trial design. FOCUS4 is also part of a recently funded Medical Research Council (MRC)–Cancer Research UK Stratified Medicine Program (Stratification in Colorectal Cancer [S-CORT]) [8]; one of the work streams specifically focuses on developing new molecular stratifiers for the FOCUS4 trial.

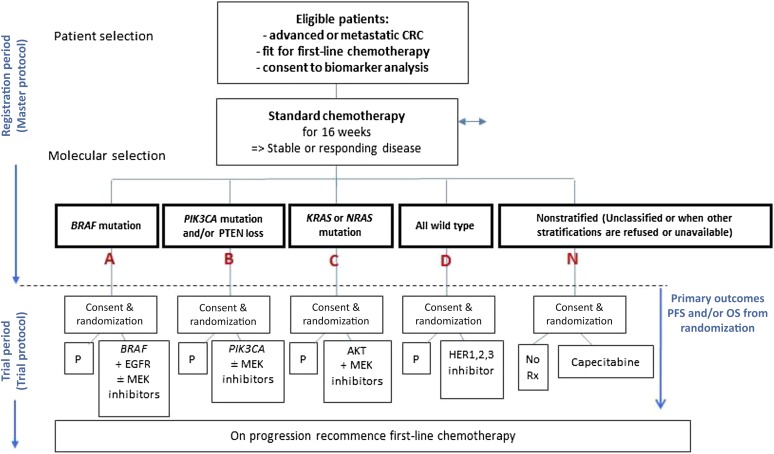

The design of FOCUS4 overcomes the inefficiencies and compromises inherent in most biomarker-stratified trials. The vast majority of mCRC patients are eligible for this trial, thus maximizing timely and efficient recruitment and ensuring the largest possible number of patients can benefit. An inclusive clinical trial design is also attractive to patients and patient advocacy groups, funding bodies, and pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and diagnostic companies. The trial design is flexible; currently, four molecularly defined cohorts are included with novel inhibitors selected for each biological subgroup: group A, BRAF mutant; group B, PI3 kinase mutant; group C, RAS mutant; and group D, all wild-type cohort (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of FOCUS4 trail for advanced colorectal cancer.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase enzymes; N, nonstratified; OS, overall survival; P, placebo; PFS, progression-free survival; Rx, prescription. Modified from Kaplan et al. [7].

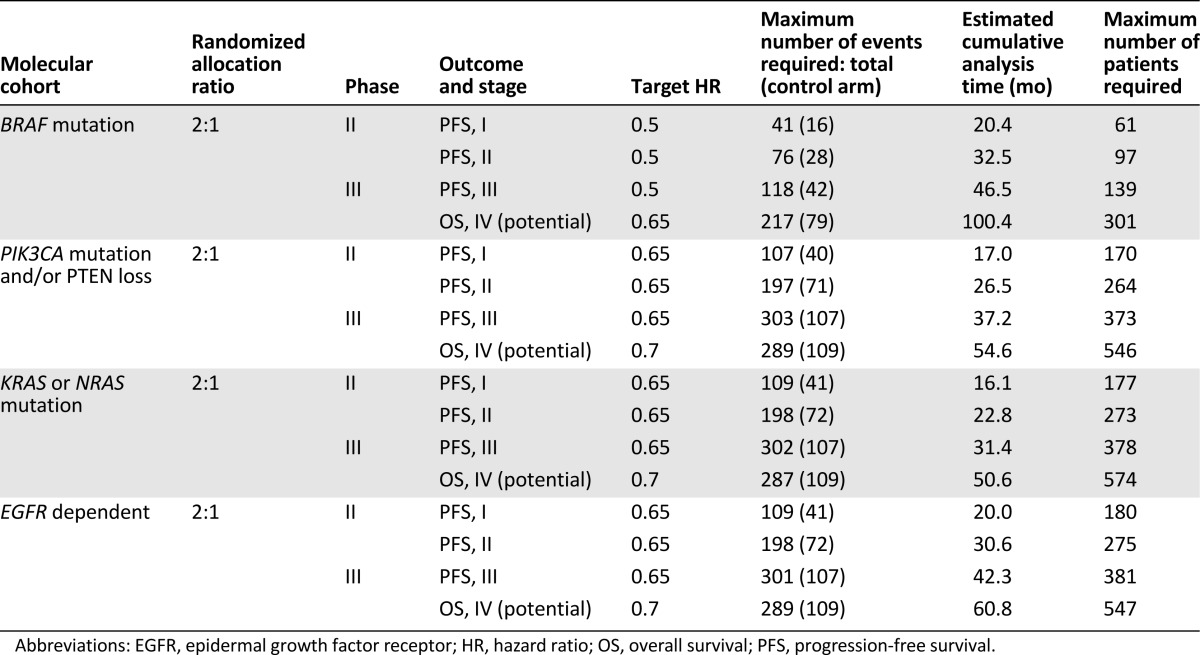

Statistical considerations are a key component of our innovative trial design [7, 9] and are indicated in detail in Table 1. A specific priority order has been established for allocating patients who could potentially fit into more than one biomarker cohort. This priority depends on, first, how closely the targeted agent appears to be linked to the biomarker (e.g., BRAF mutation and combined BRAF pathway inhibition for FOCUS4-A) and, second, on the size of the cohort. These prioritization decisions, like other aspects of the trial, also can be improved or refined during the course of the study based on developing biomarker evidence. When new developments (inevitable in this fast-moving field) are supported by an appropriate evidence base, other validated biomarkers, new cohorts, or other novel agents can be added (or substituted for ineffective treatment arms), all by amendment rather than by developing an entirely separate new trial.

Table 1.

Estimates of sample sizes for FOCUS4 trial

The BRAF mutant subgroup is an example of a cohort in which adding a multiarm comparison into the design is helpful, both to clarify underlying biology and to maximize therapeutic efficacy. BRAF inhibitor monotherapy is normally ineffective in mCRC, as escape signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) occurs [10]. Downstream inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase enzymes (MEKs) can reduce aberrant signal transduction. Thus, a multiarm trial design comparing BRAF tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitor (BRAFi) + MEK inhibitor + EGFR monoclonal antibody (mAb) versus BRAFi + EGFR mAb versus placebo allows two relevant questions to be answered in parallel: (a) does combined targeting of the mutant BRAF TK plus its feedback signaling through EGFR improve progression-free survival in BRAF mutant mCRC, and (b) is the additional inhibition of downstream MEK essential or additive to this benefit?

The design of our trial promotes efficiency, significantly shortening the recruitment time and thus the overall trial duration. This allows novel therapies to be evaluated quickly, with a commensurate reduction in costs compared with multiple individual two-arm trials that test each novel therapy in isolation. More importantly, this approach increases the likelihood of therapeutic success, which is further enhanced by the biomarker-stratified design. Crucially, the multistage statistical design allows agents with insufficient activity to be reliably identified at an early stage (and potentially replaced), and the biomarker enrichment strategy used can be tested and validated in the later stages of the trial, together maximizing the ability to identify true clinical benefit. Repetitive tumor resampling is built into the trial to counter the effects of potential tumor heterogeneity

Our increasing knowledge of the molecular taxonomy of cancer, informed by The Cancer Genome Atlas project and the International Cancer Genome Consortium, is fueling a number of biomarker-driven clinical trial initiatives, both specifically in colorectal cancer (e.g., SPECTAcolor [Screening Patients for Efficient Clinical Trial Access in Advanced Colorectal Cancer], which uses the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer SPECTA Biomarker screening platform [11], and MODUL [a biomarker-driven randomized clinical trial in mCRC] [12]) and more generally in multiple cancers (e.g., the National Cancer Institute’s Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice [NCI-MATCH], which has approximately 20 arms, each addressing a particular molecular profile [13]).

The increasing fragmentation of clinically recognized diseases into multiple separate biologically defined subtypes threatens the current cornerstone of evidence-based medicine—the randomized controlled trial. Multiarm, multistage trials, such as STAMPEDE (Systemic Therapy in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy: A Multi-Stage Multi-Arm Randomised Controlled Trial) [14], and the incorporation of biomarker stratification, such as in FOCUS4, emphasize the changing paradigm of clinical trial design, charting a course for the effective evaluation of novel therapies and the identification of the responsive patient subgroup(s) that maintains the rigor of a randomized controlled trial but allows its successful adaptation to the era of stratified medicine.

Acknowledgment

Funded by a grant from the Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Mark Lawler, Rick Kaplan, Richard H. Wilson, Tim Maughan

Collection and/or assembly of data: Mark Lawler, Rick Kaplan, Richard H. Wilson, Tim Maughan

Data analysis and interpretation: Mark Lawler, Rick Kaplan, Richard H. Wilson, Tim Maughan

Manuscript writing: Mark Lawler, Rick Kaplan, Richard H. Wilson, Tim Maughan

Final approval of manuscript: Mark Lawler, Rick Kaplan, Richard H. Wilson, Tim Maughan

Disclosures

Rick Kaplan: Celldex Therapeutics; Richard H. Wilson: Merck Serono, Sanofi Oncology (C/A); Tim Maughan: Vertex (C/A). The other author indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doroshow JH, Sleijfer S, Stupp R, et al. Cancer clinical trials—Do we need a new algorithm in the age of stratified medicine? The Oncologist. 2013;18:651–652. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehl KL, Arora NK, Schrag D, et al. Discussions about clinical trials among patients with newly diagnosed lung and colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma MR, Schilsky RL. Role of randomized phase III trials in an era of effective targeted therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;9:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parmar MKB, Carpenter J, Sydes MR. More multiarm randomised trials of superiority are needed. Lancet. 2014;384:283–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan R, Maughan T, Crook A, et al. Evaluating many treatments and biomarkers in oncology: A new design. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4562–4568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burki T. UK and US governments to fund personalised medicine. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e108. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmar MKB, Barthel FM-S, Sydes M, et al. Speeding up the evaluation of new agents in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1204–1214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacombe D, Tejpar S, Salgado R, et al. European perspective for effective cancer drug development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:492–498. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmoll H, Arnold D, De Gramont A, et al. MODUL—A multicentre randomised clinical trial of biomarker-driven therapy for 1st-line maintenance treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC): A signal-seeking approach. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(suppl 4):iv167–iv209. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conley BA, Doroshow JH. Molecular analysis for therapy choice: NCI MATCH. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:297–299. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sydes MR, Parmar MK, Mason MD, et al. Flexible trial design in practice—Stopping arms for lack-of-benefit and adding research arms mid-trial in STAMPEDE: A multi-arm multi-stage randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:168. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]