Abstract

To evaluate the genetic diversity among 48 genotypes of chickpea comprising cultivars, landraces and internationally developed improved lines genetic distances were evaluated using three different molecular marker techniques: Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR); Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) and Conserved DNA-derived Polymorphism (CDDP). Average polymorphism information content (PIC) for SSR, SCoT and CDDP markers was 0.47, 0.45 and 0.45, respectively, and this revealed that three different marker types were equal for the assessment of diversity amongst genotypes. Cluster analysis for SSR and SCoT divided the genotypes in to three distinct clusters and using CDDP markers data, genotypes grouped in to five clusters. There were positive significant correlation (r = 0.43, P < 0.01) between similarity matrix obtained by SCoT and CDDP. Three different marker techniques showed relatively same pattern of diversity across genotypes and using each marker technique it’s obvious that diversity pattern and polymorphism for varieties were higher than that of genotypes, and CDDP had superiority over SCoT and SSR markers. These results suggest that efficiency of SSR, SCOT and CDDP markers was relatively the same in fingerprinting of chickpea genotypes. To our knowledge, this is the first detailed report of using targeted DNA region molecular marker (CDDP) for genetic diversity analysis in chickpea in comparison with SCoT and SSR markers. Overall, our results are able to prove the suitability of SCoT and CDDP markers for genetic diversity analysis in chickpea for their high rates of polymorphism and their potential for genome diversity and germplasm conservation.

Keywords: Chickpea, Genetic diversity, SSR, SCoT, CDDP

Introduction

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is an important agricultural crop and 4th most important grain-legume crop after soybean, bean, and pea (Upadhyaya et al. 2008). Chickpea is an important grain legume as a cheap protein source in most developing countries in Asia and Africa. (Saeed et al. 2011; Jannatabadi et al. 2014). Assessment of the genetic diversity within crop germplasm is fundamental for breeding and conservation of genetic resources, and is particularly useful as a general guide in the choice of parents for breeding hybrids (Talebi et al. 2008a). The conservation and use of diverse collections of plant genetic resources is the backbone in plant breeding programs, so this genetic variability is the raw material for crop breeding industry on which selection acts to evolve superior genotypes (Saeed et al. 2011; Upadhyaya et al. 2008). Molecular genetic markers have been widely used in the last decades for both assessment of original material and search for valuable plant phenotypes. Genetic diversity in the chickpea has been explored using a range of molecular markers such as SSR (Saeed et al. 2011; Ghaffari et al. 2014), RAPD (Talebi et al. 2008b) and AFLP (Talebi et al. 2008a). More recent studies have demonstrated that highly polymorphic and Co-dominant SSR markers can be used for gene mapping and diversity fingerprinting in chickpea (Winter et al. 2000; Saeed et al. 2011; Jannatabadi et al. 2014; Ghaffari et al. 2014). Thus, SSR markers can be widely used for constructing chickpea related genetic linkage maps (Winter et al. 2000; Lichtenzveig et al. 2005; Jamalabadi et al. 2013). However, development of SSR markers requires sequence information’s and this method is not feasible in the most laboratories with only standard agarose gel electrophoresis. Therefore, developments of new molecular markers that do not require genome sequence database are fundamental. Today, using the huge genomics information’s in public biological database is an alternative, fast and cheap method for development of new molecular markers that encode certain candidate genes (Andersen and Lubberstedt 2003). Initiating a trend away from random DNA markers towards gene-targeted markers, a novel marker systems like Conserved DNA-Derived Polymorphism (CDDP) (Collard and Mackill 2009a) and Start Codon Targeted Polymorphism (SCoT) (Collard and Mackill 2009b) were developed based on the conserved regions. These are typically functional domains which correspond to conserved DNA sequences within genes. Molecular markers that developed based of conserved regions of genome across different plant species, like as SCoT and CDDP, due to longer primers with higher annealing temperature will be more reliable and reproducible that arbitrary markers like as RAPDs or DAFs. Furthermore, this method focuses on gene regions which may have advantages over random markers for applications in QTL mapping (Andersen and Lubberstedt 2003). The use of CDDP markers for studying genetic diversity has been reported here for the first time in chickpea genotypes. The aim of the present study was to determine the efficiency of two gene-based markers (SCoT and CDDP) compared to SSR markers in diagnostic fingerprinting of chickpea genotypes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Forty eight chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) accessions comprising 19 landrace accessions from different geographical location of Iran and 29 improved genotypes provided by Iranian Seed and Plant Improvement Institute (SPII) and International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) were considered for the study of genetic variation using SSR, SCoT and CDDP molecular markers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of 48 chickpea genotypes tested, including pedigree and origin/source

| Entry no. | Name | Pedigree-(Origin) | Entry no. | Name | Pedigree- (Origin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L7 | Landrace (Khoy- north west of Iran) | 25 | L45 | Landrace (Kerman- south of Iran) |

| 2 | CCV2 | Short term check-(ICARDA) | 26 | L33 | Landrace (Moghan- north of Iran) |

| 3 | ILC482 | Drought tolerance check-(Iran) | 27 | LMR29 | x99TH151/ILC3805xILC5901-(ICARDA) |

| 4 | Flip2005.5c | X99TH154/ILC5901XILC3397-(ICARDA) | 28 | ILC1929 | Not traced-(ICARDA) |

| 5 | LMR144 | X99TH154/ILC5901XILC3397-(ICARDA) | 29 | Arman | Not traced-Iran |

| 6 | 8EL93IM2446 | Not traced- (ICARDA) | 30 | ILC3279 | Landrace/Long term check-(ICARDA) |

| 7 | L28 | Landrace (Jahrom-south of Iran) | 31 | Flip2005.1c | x99TH151/ILC3805xILC3397 |

| 8 | L69 | Landrace (Ormiyed- north west of Iran) | 32 | LMR153 | x99TH154/ILC5901xILC3397 |

| 9 | L38 | Landrace (Torbat- North east of Iran) | 33 | ILC588 | Short term check –(ICARDA) |

| 10 | Azad | Not traced-Iran | 34 | Flip2005.3c | x99TH154/ILC5901xILC3397 |

| 11 | L26 | Landrace (Turkey) | 35 | LMR81 | x99TH153/ILC3805xILC5309 |

| 12 | L18 | Landrace (Torbat- North east of Iran) | 36 | Piruz | Not traced-Iran |

| 13 | Hashem | Not traced-Iran | 37 | L32 | Landrace (Khoy- north west of Iran) |

| 14 | Flip03-45c | ×99TH 6/FLIP91-14C × FLIP90-19C | 38 | L5 | Landrace (Torbat- North east of Iran) |

| 15 | L13 | Landrace (Karaj- north of Iran) | 39 | L58 | Landrace (Cupreous) |

| 16 | L21 | Landrace (Torbat- North east of Iran) | 40 | Flip04-20c | ×00 TH35/FLIP 98-25C × S99442-(ICARDA) |

| 17 | L60 | Landrace (Cupreous) | 41 | Flip01-48c | X98TH30/FLIP 93-55C x S 96231-(ICARDA) |

| 18 | ILC533 | Not traced-(ICARDA) | 42 | Kaka | Not traced-Iran |

| 19 | Flipo3.27c | X98TH86/[(ILC267XFLIP89-4C)XHB-1])XS95345-(ICARDA) | 43 | Jam | Not traced-Iran |

| 20 | L37 | Landrace-(Iran) | 44 | ILC3397 | Not traced-(ICARDA) |

| 21 | ILC263 | Susceptible Ascochyta blight check -(ICARDA) | 45 | Flip5187-3C | Drought tolerance check-(ICARDA) |

| 22 | L50 | Landrace (Ardabil- north of Iran) | 46 | LMR165 | x99TH155/ILC5901xILC5309-(ICARDA) |

| 23 | L68 | Landrace (Nayshabor-north east of Iran) | 47 | L17 | Landrace-(Iran) |

| 24 | LMR159 | X99TH154/ILC5901XILC3397- (ICARDA) | 48 | LMR134 | x99TH154/ILC5901xILC3397- (ICARDA) |

Genomic DNA extraction and SSR analysis

Total genomic DNA was extracted from a pool of ten plants of each accession following a CTAB extraction protocol (Lassner et al. 1989). A total of 15 microsatellite markers were screened in the genotypes of which 10 were polymorphic (Table 2). The SSR markers were synthesized as per the sequences of Winter et al. (2000) from Cinagene, Iran.

Table 2.

Description (denomination, sequence, repeats) of the polymorphic microsatellite markers used in the genetic diversity analysis of 48 chickpea genotypes

| Microsattelite | Primer sequence | Repeat | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |||

| Ts72 | caaacaatcactaaaagtatttgctct | aaaaattgatggacaagtgttattatg | (ATT)39 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA47 | tttttataggtgtctttttgttgtcttt | tctgaataggaaataagaaaggtaggtt | (TAA)21 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA37 | acttacatgaattatctttcttggtcc | cgtattcaaataatctttcatcagtca | (TTA)20 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA25 | agtttaattggctggttctaagataac | aggatgatctttaataaatcagaatga | (TAA)45 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA130 | tctttctttgcttccaatgt | gtaaatcccacgagaaatcaa | (TAA)19 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| Ts45 | tgacacaaaattgtctcttgt | tgttcttaacgtaactaacctaa | (TAA)8(A)3(TAA)18 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA146 | ctaagtttaatatgttagtccttaaattat | acgaacg(c)aacattaattttatatt | (TTA)29 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA72 | ggtcaacatgcataagtaatagcaata | actttcgcgattcagctaaaata | (ATT)36 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA3 | aatctcaaaattccccaaatt | atcgaggagagaagaaccat | (TAA)11 | Winter et al. 2000 |

| TA39 | ttagcgtggctaactttatttgc | ataaatatccaattctggtagttgacg | (TAA)20 | Winter et al. 2000 |

The SSR markers amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a volume of 20 μl, containing 15 ng genomic DNA, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Cinagene), 2 μM of each primer, 100 μM of each dNTP (Cinagene), 2 μl (10×) PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Cinagene) and ddH2O, using a Eppendorf PCR System (Master Cycler Gradiant, Eppendorf). Amplification was carried for 38 cycles, each consisting of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 50–60 °C for 1 min and an extension step at 72 °C for 2 min. PCR products were analyzed using 3 % methaphor agarose electrophoresis gels stained with ethidium bromide. Frequencies of incidence of all polymorphic alleles for each SSR markers were calculated and used for determining statistical parameters. Each bands identified as an allele and scored as ‘a1’, ‘a2’ etc., from largest to smallest sized band. Cluster analysis was conducted on the basis of unrooted NJ tree using similarity matrix was carried through DARwin 5.0.128 (Perrier et al. 2003). Node construction according to bootstrap analysis using 1000 bootstrap values was performed. Number of allele (Na), effective number of alleles (Ne), gene diversity (He) and polymorphism information content (PIC) were calculated by GENALEX 6.1 software (Peakall and Smouse 2006).

SCoT and CDDP analysis

Nine SCoT primers used in this study developed by Collard and Mackill (2009b) (Table 3). All primers were 18-mer and ranged in GC content between 50 and 72 %. Ten CDDP primer sequences employed in the present study were designed by Collard and Mackill (2009a) based on the protein sequences of well-characterized genes from diverse plant species (Table 4). Sequences of these genes were scanned for short conserved amino acid regions with the low permutations of possible codons. Up to three degenerate nucleotides were included in a single primer. Since plant exons are typically guanine–cytosine (GC) rich, some degeneracies were incorporated into primers corresponding to the third nucleotide position of a codon (i.e., G or C in the primer sequence was designed as an “S”). Primers were 15 to 19 nucleotides in length and had >60 % GC content. PCR amplification was performed in 20 μl reaction containing 1× PCR buffer, 50 ng sample DNA, 2.5 μM primer, 200 μM of each dNTP, 3 mM MgCl2 and 1.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Cinnagen, Iran). All amplification were carried out in a Eppendorf thermocyclers as follows: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 93 °C for 1 min, annealing at 48 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. A final extension cycle at 72 °C for 10 min was followed. PCR products were separated on 1.5 % agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and scored for the presence or absence of bands.

Table 3.

Primers used in SCoT analyses

| Primer | Sequemces (5/ to 3/) | GC% | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCoT36 | gcaacaatggctaccacc | 55 | 48 |

| SCoT28 | ccatggctaccaccgcca | 66 | 48 |

| SCoT20 | accatggctaccaccgcg | 66 | 48 |

| SCoT11 | aagcaatggctaccacca | 50 | 48 |

| SCoT1 | caacaatggctaccacca | 50 | 48 |

| SCoT35 | catggctaccaccggccc | 72 | 48 |

| SCoT2 | caacaatggctaccaccc | 55 | 48 |

| SCoT22 | tacatcgcaagtgacacagg | 55 | 48 |

| SCoT13 | acgacatggcgaccatcg | 61 | 48 |

Table 4.

Conserved DNA sequence targets and CDDPs primer sequences and details

| Gene | Gene function | Amino acid motif | Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | GC(%) | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABP1 | Auxin-binding protein | TPIHR | ABP1-1 | acsccsatccaccgc | 73 % | 50 °C |

| HEDVQ | ABP1-3 | cacgaggacctscagg | 69 % | 51 °C | ||

| WRKY | Transcription factor for developmental and physiological roles | WRKYGQ | WRKYR1 | gtggttgtgtcttgcc | 60 % | 52 °C |

| GKHNH | WRKYF1 | tggcgsaagtacggccag | 67 % | 53 °C | ||

| MYB | Unknown (implicated in secondary metabolism, abiotic and bioticnstresses, cellular morphogenesis) | GKSCR | Myb1 | ggcaagggctgccgc | 80 % | 54 °C |

| GKSCR | Myb2 | ggcaagggctgccgg | 80 % | 55 °C | ||

| ERF | Transcription factor involved in plant disease resistance pathway | HYRGVR | ERF1 | cactaccccggsctscg | 77 % | 56 °C |

| AEIRDP | ERF2 | gcsgagatccgsgaccc | 77 % | 57 °C | ||

| KNOX | Homeobox genes that function as transcription factors with a unique homeodomain | KGKLPK | Knox1 | aagggsaagctsccsaag | 61 % | 58 °C |

| HWWELH | Knox2 | cactggtgggagctscac | 67 % | 59 °C |

DNA bands obtained with SCoT and CDDP markers were scored visually for the presence (1) and absence (0) of bands for all the 48 accessions. Pair-wise genetic distance and similarity matrix constructed by DARwin version 5.0 (Perrier et al. 2003). Cluster analysis using the neighbour-joining analyses (UNJ) (Gascuel 1997) were performed by using the similarity matrix and followed by bootstrap analysis with 1000 permutations to obtain a dendrogram for all the 48 accessions (Perrier et al. 2003). Mantel statistic was used to compare the similarity matrices as well as the dendrograms produced by the SSR, CDDP and SCoT techniques. All these procedures were performed by appropriate routines in NTSYSpc version 2.0 (Rohlf 1998).

Results

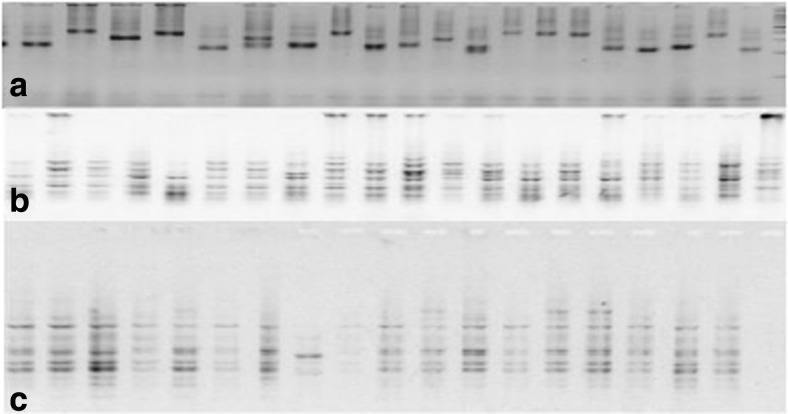

DNA fingerprinting database was produced using three different PCR-based molecular marker systems (SSR, SCoT and CDDP) for 48 chickpea genotypes collected from different sources. Our results indicated that primers obtained from different regions of genomic DNA successfully amplified genotype DNAs (Fig. 1). All of the three molecular marker setes were able to distinguish and identify each of 48 chickpea genotypes. Salient features of fingerprinting database obtained using SSR, SCoT and CDDP markers are given below.

Fig. 1.

Amplification profile obtained with TA39 (a), SCoT 28 (b) and Myb2 (c) primers detected in chickpea genotypes

SSR markers polymorphism pattern

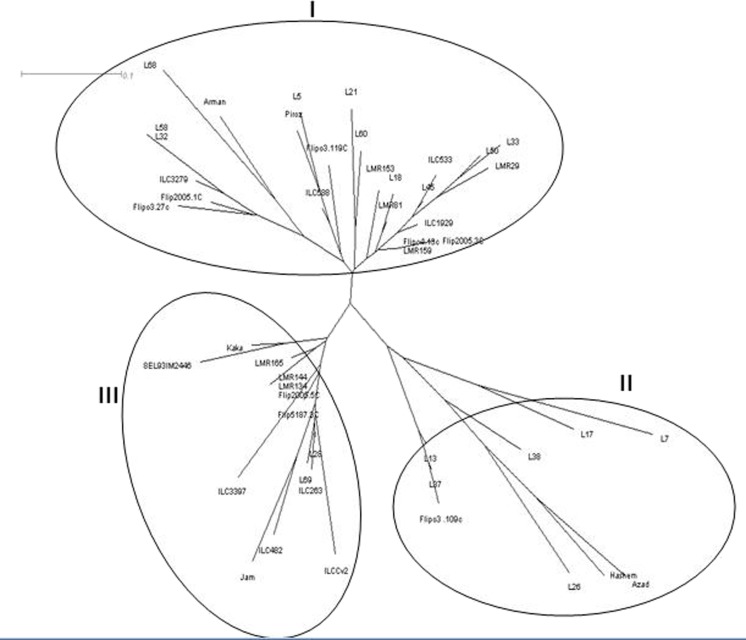

In the present study, the 10 SSR loci analyzed produced 31 alleles with an average 3.1 alleles per marker. The number of alleles (na) ranged from 2 to 4 with an average of 2.26, whereas the maximum was observed in TA25, Ts72 and TA39. The effective allelic number (ne) ranged from 1.23 to 3.24 with an average of 2.26 (Table 5). The observed heterozygosity (Ho) ranged from 0.00 to 1 with average of 0.55. The expected heterozygosity (He) ranged from 0.17 to 0.70 with average of 0.51 (Table 5). PIC ranged from 0.17 (TA72) to 0.70 (Ts72) with an average of 0.47. Primers with a higher number of alleles (Ts72, TA25 and TA39) showed higher PIC values (Table 5). The Shannon’s information index (I) ranged from 0.33 (TA130) to 1.26 (Ts72) with an average of 0.86 among SSR loci (Table 5). The number of alleles per locus showed a significant and positive relationship with both PIC (r = 0.52, P < 0.01) and gene diversity (r = 0.64, P < 0.01). Genotypes grouped into three major clusters (Fig. 2). Cluster I contained 25 genotypes, comprising of ten Iranian landrace accessions were collected from north and north-east of Iran and two Iranian improved cultivars (Arman and Piroz) (Fig. 2). Cluster II contained nine genotypes, out of which six of them were Iranian landrace accessions collected from north-west of Iran and two were Iranian improved cultivars (Azad and Hashem). Flip03-109C also grouped in this cluster. Remaining genotypes were grouped in third cluster that mainly originated from ICARDA (Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Allele number (na), effective allele number (ne), shanon index (I), heterozygosity (HO) and polymorphism information content (PIC) obtained after screening 48 chickpea genotypes at 10 SSR loci analyzed in this study

| Marker | Number of allele (na) | Number of effective allele (ne) | Shanon index (I) | Observed hetrozygosity (Ho) | Expected hetrozygosity (He) | Polymorphism information content (PIC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA130 | 2 | 1.23 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| TA25 | 4 | 3.01 | 1.21 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| TS72 | 4 | 3.24 | 1.26 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| TA47 | 3 | 2.57 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.62 | 0.61 |

| TA37 | 3 | 2.46 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| TS 45 | 3 | 1.57 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.05 |

| TA146 | 3 | 2.52 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.60 |

| TA72 | 3 | 1.21 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| TA3 | 2 | 1.97 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| TA39 | 4 | 2.89 | 1.16 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

Fig. 2.

Dendrogram of the 48 chickpea genotypes based on the dissimilarity matrix developed using SSR markers

SCoT markers polymorphism pattern

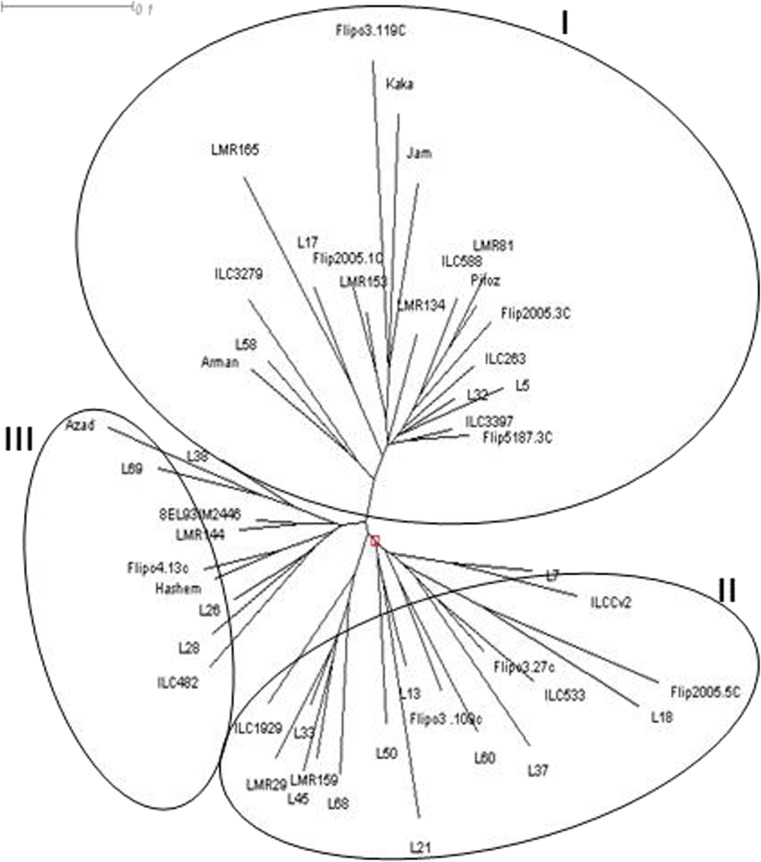

A set of 9 SCoT primers were used to fingerprint 48 chickpea genotypes. A total of 145 bands were detected among 48 chickpea genotypes using 9 SCoT markers out of which 133 were polymorphic (Table 6). Number of polymorphic bands were ranged from 10 (SCoT1) to 20 (SCoT13) with an average 14.7 per primers. PIC values ranged from 0.43 to 0.47, with an average value of 0.45 per primer (Table 6). The 48 chickpea accessions fell under three major groups (Fig. 3). Cluster I contained 20 genotypes included four Iranian improved cultivars, four landrace accessions and 12 genotypes originated from ICARDA. Cluster II contained 18 genotypes, which 10 of them were landrace accessions were collected from north west and north east of Iran. Ten genotypes grouped in cluster three which six of them are improved genotypes and remained four genotypes are landrace accessions were collected from different geographical sites of Iran (Fig. 3).

Table 6.

Polymorphism and PIC values in chickpea genotypes as revealed by SCoT and CDDP markers

| Marker | Number of amplified bands | Number of polymorphic bands | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCoT | |||

| SCoT28 | 13 | 12 | 0.46 |

| SCoT35 | 18 | 13 | 0.46 |

| SCoT13 | 21 | 20 | 0.46 |

| SCoT 1 | 12 | 10 | 0.46 |

| SCoT36 | 15 | 13 | 0.45 |

| SCoT2 | 18 | 18 | 0.46 |

| SCoT22 | 16 | 15 | 0.47 |

| SCoT20 | 14 | 14 | 0.43 |

| SCoT11 | 18 | 18 | 0.47 |

| CDDP | |||

| ABP1-1 | 17 | 17 | 0.48 |

| ABP1-3 | 16 | 16 | 0.46 |

| WRKYR1 | 10 | 9 | 0.40 |

| WRKYF1 | 19 | 19 | 0.49 |

| Myb1 | 15 | 15 | 0.45 |

| Myb2 | 11 | 10 | 0.45 |

| ERF1 | 16 | 16 | 0.46 |

| ERF2 | 14 | 9 | 0.43 |

| Knox1 | 18 | 15 | 0.46 |

| Knox2 | 15 | 15 | 0.46 |

Fig. 3.

Dendrogram of the 48 chickpea genotypes based on the dissimilarity matrix developed using SCoT markers

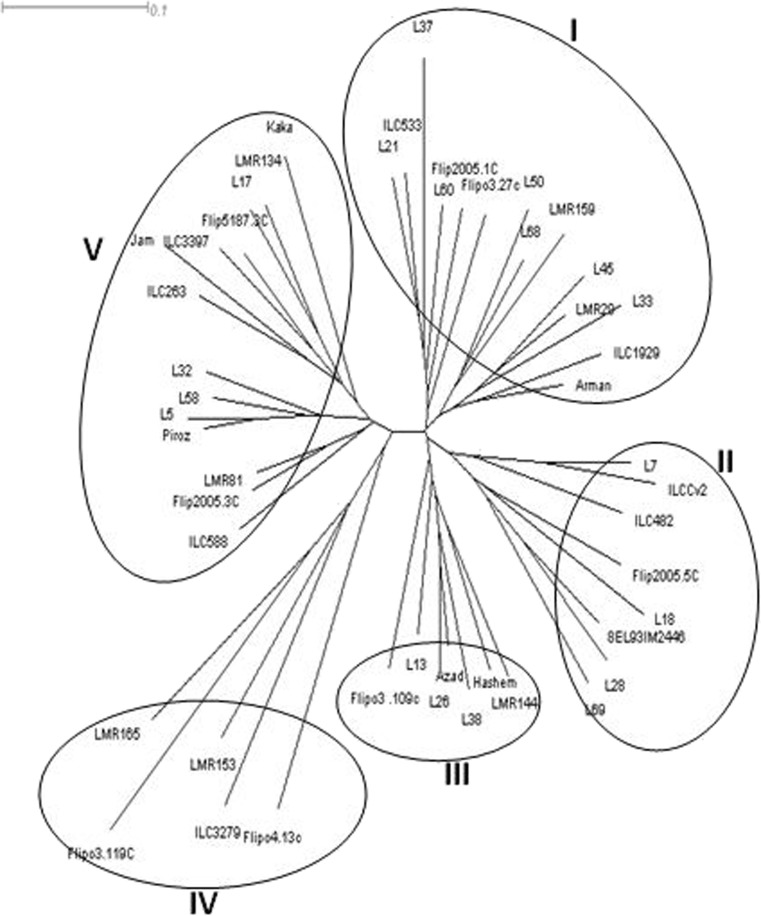

CDDP markers polymorphism pattern

Ten primers generated a total of 151 bands out of which 141 were polymorphic (Table 6). The number of polymorphic bands were ranged from 9 (WRKYR1 and ERF2) to 17 (ABP1-1) with an average of 14.1 bands per primers. PIC values ranged from 0.43 to 0.49, with an average value of 0.45 per primer (Table 6). Based on un-weighted neighbour-joining method, the 48 chickpea genotypes grouped in five distinct clusters (Fig. 4). First cluster contained 14 genotypes of which 7 were Iranian accessions mainly collected from north-east of Iran and remaining genotypes originated from ICARDA. Cluster II and III contained 9 and 7 genotypes, respectively, which were landrace accessions from north-west of Iran. Cluster IV contained 5 genotypes all of which originated from ICARDA. Cluster V contained 13 genotypes which four were improved cultivars (Kaka, Jam, ILC3279, Piroz and ILC588) cultivated in most chickpea growing area of Iran and four landrace accessions from north-west of Iran (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Dendrogram of the 48 chickpea genotypes based on the dissimilarity matrix developed using CDDP markers

Correlation between the similarity values measured using three marker systems

Cophenetic coefficient were acceptable in all three molecular markers systems (SSR = 0.79; SCoT = 0.84 and CDDP = 0.86) indicating good fit for clustering. Positive correlations were observed between all the three marker types by mantel test. The correlation coefficient (r) was 0.13 between SSR and SCoT, 0.15 between SSR and CDDP and 0.47 (significant P > 0.05) between CDDP and SCoTs.

Discussion

Evaluation of genetic diversity and an understanding of the genetic relationships in the germplasm collection provide useful information to address breeding programmes and also confirm the usefulness of diverse germplasm in crop breeding programs. Chickpea have a narrow genetic background (Nguyen et al. 2004) and looking for desirable traits is fundamental for varietal improvement in different breeding strategies. This narrow genetic base and lack of genes associated with various biotic and abiotic stresses leads to slow improvement in chickpea yield potential. Introducing the genes conferring resistance to different biotic and abiotic stresses from different primary gene pool can lead to increase in the yield of chickpea (Choudhary et al. 2012). In the current study, three different marker data-sets, SSR, SCoT and CDDP were used for analysis the genetic diversity within a set of 48 diverse chickpea genotypes to know if these marker systems can be effectively used in breeding programme. Our study using different marker sets suggested the presence of a considerable polymorphism and showed high level of diversity in studied chickpea genotypes which is in agreement with those reported by Saeed et al. (2011) and Ghaffari et al. (2014). These finding are contrary to the findings of Iruela et al. (2002) and Choudhary et al. (2012), who reported low level of genetic diversity within chickpea germplasm. Our finding may be due to the use of different and novel marker systems (SCoT and CDDP) compared to previous studies by different researchers that used morphological and SSR markers. The clustering pattern relatively showed the existence of definite pattern of relationships between geographical origins and genetic diversity and it’s obviously demonstrated that genotypes from the same geographical origin characteristically fall exclusively in a single or two clusters. Some clusters constituted genotypes mostly from the same geographical origin while others had genotypes from more than one sources and, hence, the number of entries varied from cluster to cluster. The SCoT and CDDP marker techniques were employed in the present study for several reasons. Firstly, these are types of targeted molecular marker techniques characterized by simplicity and reproducibility. The PCR products were resolved by performing agarose gel electrophoresis. On other hand, PCR amplification using gene-specific primers targets conserved DNA regions within genes (Hamidi et al. 2014). In this study, the amount of polymorphisms and efficiency of generating polymorphism by SCoT and CDDP markers were compared with SSR (Tables 5 and 6). Evidently, the SCoT and CDDP markers technique could detect more polymorphic primers and higher polymorphism compared to SSR markers in chickpea (Tables 5 and 6). But, it is difficult to compare the polymorphism rate of SCoT and CDDP markers used in this study with other studied used different dominant markers (such as RAPD, AFLP or ISSR) because of the difference in the number of primers, accessions, and varieties used. Our results showed that average polymorphism rates within genotypes for SSR, SCoT and CDDP primers was high and relatively is on the same level (Tables 5 and 6). Although the extent of diversity for the three marker techniques was approximately equal; we anticipate that the source of detected diversity is different, as each technique targets different regions of the genome. Discordance between dendograms obtained by SCoT and CDDP with SSR could be explained by the different nature of each techniques, region coverage of genome by each markers, level of polymorphism and the number of loci (Souframanien and Gopalakrishna 2004; Gorji et al. 2011). Our results substantiate the previous reports by clustering genotypes using different marker systems in potato (Gorji et al. 2011), Chickpea (Pakseresht et al. 2013) and wheat (Hamidi et al. 2014). Mantel coefficient correlation test showed higher positive correlation between SCoT and CDDP metrices, indicating a consistent relationship between genetic distances from both marker systems. This higher correlation may have been attributable to similarity in DNA sequence variation at primer binding sites between the SCoT and CDDP techniques. The current study confirmed the importance of new functionally gene-based molecular studies (SCoTs and CDDPs as cheap, fast and informative markers) that can be used beside the SSR markers data in detecting genetic variation among genotypes in selecting diverse parents to carry out a new crossing program successfully. In summary, two novel DNA marker systems that targets candidate plant genes in comparison with SSR markers were used for genetic diversity analysis in chickpea. More importantly, SCoT and CDDP markers are generated from the functional region of the genome; the genetic analyses using these markers would be more useful for crop improvement programs, such as assessing genetic diversity, genotype identification, construction of linkage maps, and QTL mapping.

Abbreviations

- SSR

Simple sequence repeat

- SCoT

Strat codon targeted

- CDDP

Conserved DNA-derived polymorphism

References

- Andersen JR, Lubberstedt T. Functional markers in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:554–560. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary P, Khanna SM, Jain PK, Bharadwaj C, Kumar J, Lakhera PC, Srinivasan R. Genetic structure and diversity analysis of the primary gene pool of chickpea using SSR markers. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11(2):891–905. doi: 10.4238/2012.April.10.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collard BCY, Mackill DJ. Conserved DNA-derived polymorphism (CDDP): a simple and novel method for generating DNA markers in plants. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2009;27:558–562. doi: 10.1007/s11105-009-0118-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collard BCY, Mackill DJ. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism: a simple, novel DNA marker technique for generating gene-targeted markers in plants. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2009;27:86–93. doi: 10.1007/s11105-008-0060-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gascuel O. BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14(7):685–695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari P, Talebi R, Keshavarz F. Genetic diversity and geographical differentiation of Iranian landrace, cultivars and exotic chickpea lines as revealed by morphological and microsatellite markers. Physiol Mol Biol Plant. 2014;20(2):225–233. doi: 10.1007/s12298-014-0223-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorji AM, Poczai P, Polgar Z, Taller J. Efficiency of arbitrarily amplified dominant markers (SCOT, ISSR and RAPD) for diagnostic fingerprinting in tetraploid potato. Am J Potato Res. 2011;88:226–237. doi: 10.1007/s12230-011-9187-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi H, Talebi R, Keshavarz F. Comparative efficiency of functional gene-based markers, start codon targeted polymorphism (SCoT) and conserved DNA-derived Polymorphism (CDDP) with ISSR markers for diagnostic fingerprinting in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Cereal Res Commun. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Iruela M, Rubio J, Cubero JI, Gil J, Milan T. Phylogenetic analysis in the genus Cicer and cultivated chickpea using RAPD and ISSR markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s001220100751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamalabadi JG, Saidi A, Karami E, Kharkesh M, Talebi R. Molecular mapping and characterization of genes governing time to flowering, seed weight and plant height in an intraspecific genetic linkage map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Biochem Genet. 2013;51:387–397. doi: 10.1007/s10528-013-9571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannatabadi AA, Talebi R, Armin M, Jamalabadi J, Baghebani N. Genetic diversity of Iranian landrace chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) accessions from different geographical origins as revealed by morphological and sequence tagged microsatellite markers. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;23(2):225–229. doi: 10.1007/s13562-013-0206-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lassner MW, Peterson P, Yoder JI. Simultaneous amplification of multiple DNA fragments by polymerase chain reaction in the analysis of transgenic plants and their progeny. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1989;7:116–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02669627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenzveig J, Scheuring C, Dodge J, Abbo S, Zhang HB. Construction of BAC and BIBAC libraries and their applications for generation of SSR markers for genome analysis of chickpea, Cicer arietinum L. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;110:492–510. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1857-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Taylor PW, Redden RJ, Ford R. Genetic diversity estimates in Cicer using AFLP analysis. Plant Breed. 2004;123:173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2003.00942.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pakseresht F, Talebi R, Karami E. Comparative assessment of ISSR, DAMD and SCoT markers for evaluation of genetic diversity and conservation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) landraces genotypes collected from north-west of Iran. Physiol Mol Biol Plant. 2013;19(4):563–574. doi: 10.1007/s12298-013-0181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R, Smouse PE. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X, Flori A, Bonnot F. Data analysis methods. In: Hamon P, Seguin M, Perrier X, Glaszmann JC, editors. Genetic diversity of cultivated tropical plants. Enfield: Science Publishers; 2003. pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ. NTSYS-pc numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. Version 2.02. Setauket: Exeter Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A, Hovsepyan H, Darvishzadeh R, Imtiaz M, Panguluri SK, Nazaryan R. Genetic diversity of iranian accessions, improved lines of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and their wild relatives by using simple sequence repeats. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2011;29:848–858. doi: 10.1007/s11105-011-0294-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souframanien J, Gopalakrishna T. Acomparative analysis of genetic diversity in black gram genotypes using RAPD and ISSR markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109:1687–1693. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebi R, Fayaz R, Mardi M, Pirsyedi SM, Naji AM. Genetic relationships among chickpea (Cicer arietinum) elite lines based on RAPD and agronomic markers. Int J Agric Biol. 2008;8:301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi R, Naji AM, Fayaz F. Geographical patterns of genetic diversity in cultivated chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) characterized by amplified fragment length polymorphism. Plant Soil Environ. 2008;54:447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya HD, Dwivedi SL, Baum M, Varshney RK, Udupa SM, Gowda CLL. Genetic structure, diversity, and allelic richness in composite collection and reference set in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter P, Benko-Iseppon AM, Hüttel B, Ratnaparkhe M, Tullu A, Sonnante G, Pfaf T, Tekeoglu M, Santra D, Sant VJ, Rajesh PN, Kahl G, Muehlbauer FJ. A linkage map of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genome based on recombinant inbred lines from a C. arietinum × C. reticulatum cross: localization of resistance genes for Fusarium wilt races 4 and 5. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;101:1155–1163. doi: 10.1007/s001220051592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]