Abstract

The inferior colliculus (IC) is an obligatory relay for ascending auditory inputs from the brainstem and receives descending input from the auditory cortex. The IC comprises a central nucleus (CNIC), surrounded by several shell regions, but the internal organization of this midbrain nucleus remains incompletely understood. We used two-photon calcium imaging to study the functional microarchitecture of both neurons in the mouse dorsal IC and corticocollicular axons that terminate there. In contrast to previous electrophysiological studies, our approach revealed a clear functional distinction between the CNIC and the dorsal cortex of the IC (DCIC), suggesting that the mouse midbrain is more similar to that of other mammals than previously thought. We found that the DCIC comprises a thin sheet of neurons, sometimes extending barely 100 μm below the pial surface. The sound frequency representation in the DCIC approximated the mouse's full hearing range, whereas dorsal CNIC neurons almost exclusively preferred low frequencies. The response properties of neurons in these two regions were otherwise surprisingly similar, and the frequency tuning of DCIC neurons was only slightly broader than that of CNIC neurons. In several animals, frequency gradients were observed in the DCIC, and a comparable tonotopic arrangement was observed across the boutons of the corticocollicular axons, which form a dense mesh beneath the dorsal surface of the IC. Nevertheless, acoustically responsive corticocollicular boutons were sparse, produced unreliable responses, and were more broadly tuned than DCIC neurons, suggesting that they have a largely modulatory rather than driving influence on auditory midbrain neurons.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Due to its genetic tractability, the mouse is fast becoming the most popular animal model for sensory neuroscience. Nevertheless, many aspects of its neural architecture are still poorly understood. Here, we image the dorsal auditory midbrain and its inputs from the cortex, revealing a hitherto hidden level of organization and paving the way for the direct observation of corticocollicular interactions. We show that a precise functional organization exists in the mouse auditory midbrain, which has been missed by previous, more macroscopic approaches. The fine-scale distribution of sound-frequency tuning suggests that the mouse midbrain is more similar to that of other mammals than previously thought and contrasts with the more heterogeneous organization reported in imaging studies of auditory cortex.

Keywords: two-photon calcium imaging, bouton, corticocollicular projection, GCaMP6, inferior colliculus, tonotopic

Introduction

Fine-scale analysis of the functional architecture of rodent sensory cortex has revealed a surprising lack of local organization, particularly in auditory cortex (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Rothschild et al., 2010; Kanold et al., 2014). Because the degree of heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of cortical response properties may be species specific (Ohki et al., 2005; Rothschild and Mizrahi, 2015), it is important to determine whether similar differences exist at subcortical levels too or whether, as suggested by studies of visual processing (Ahmadlou and Heimel, 2015; Feinberg and Meister, 2015), more precise ordering of response properties exists outside the cortex.

The inferior colliculus (IC) is the principal auditory midbrain structure and receives ascending inputs from multiple brainstem areas and descending inputs from the auditory cortex (Winer and Schreiner, 2005). Anatomically, the mouse IC appears largely consistent with other mammals. It comprises a central nucleus (CNIC) and a surrounding cortex, which can be further subdivided into the dorsal cortex (DCIC), a sheet of neurons covering the CNIC, and an external nucleus which extends lateroventrally from the DCIC (Willard and Ryugo, 1983; Willott, 2001; Oliver, 2005). In the Golgi-stained mouse brain, the DCIC has been characterized as a 300–500 μm thick, four-layered structure populated by stellate and pyramidal neurons, whereas the CNIC is made up mostly of bipolar cells whose axons and dendrites run in the same direction, and thus, give it its distinct laminated appearance (Meininger et al., 1986). Assigning a border between these regions, however, is not straightforward and its reported location varies substantially depending on the histological approach used (Willard and Ryugo, 1983; Meininger et al., 1986; Idrizbegovic et al., 1999; Paxinos and Franklin, 2001; Allen Institute for Brain Science, 2015).

Neurons in CNIC exhibit sharp frequency tuning, have low thresholds and are arranged tonotopically in isofrequency laminae with high sound frequencies represented ventromedially and low frequencies dorsolaterally (Willott and Urban, 1978; Stiebler and Ehret, 1985; Malmierca et al., 2008). Moreover, electrophysiological (Stiebler and Ehret, 1985, Willott, 1986; Romand and Ehret, 1990; Portfors et al., 2011) and imaging studies (Ito et al., 2014) suggest that, in mice, a continuous tonotopic map exists, with the high-to-low gradient running from the medioventral edge of the CNIC all the way to the surface of the IC. It is therefore unclear whether or how the anatomical and physiological properties of these regions map onto each other and it has even been proposed that, functionally, the DCIC of the mouse, unlike that of other mammals, is simply an extension of the CNIC (Willott, 2001).

Interest in the functional organization of the DCIC stems from the fact that a substantial proportion of its input originates in the auditory cortex (Saldaña et al., 1996; Winer et al., 1998; Bajo and Moore, 2005). Corticofugal modulation has a profound impact on the representation of sound features in the IC and is thought to play an important role in experience-dependent plasticity (Bajo and King, 2012; Suga, 2012). Consequently, characterizing the spatial organization of the response properties of DCIC neurons and their corticocollicular afferents will not only provide new insight into the functional architecture of the IC, but should also improve our understanding of how corticofugal feedback influences the activity of midbrain neurons.

To address these issues, we used two-photon imaging to investigate the fine-scale functional organization of cell populations and descending corticocollicular axons in the dorsal, optically accessible, part of the mouse IC. We found a highly ordered functional microarchitecture, with a precise border between the CNIC and DCIC that has been hidden to the large-scale electrophysiological approaches so far used to study the IC. This suggests that the mouse IC may be functionally more similar to that of other mammals than previously thought and organized in a similarly precise fashion to the superior colliculus in this species (Ahmadlou and Heimel, 2015; Feinberg and Meister, 2015).

Materials and Methods

All experiments were approved by the local ethical review committee at the University of Oxford and licensed by the UK Home Office. For all experiments, 24 female C57BL/6 mice were used (Harlan Laboratories).

Virus transduction.

Animals aged 4–6 weeks were premedicated with intraperitoneal injections of dexamethasone (Dexadreson, 4 μg), atropine (Atrocare, 1 μg) and carprofen (Rimadyl, 0.15 μg). General anesthesia was induced by an intraperitoneal injection of fentanyl (Sublimaze, 0.05 mg/kg), midazolam (Hypnovel, 5 mg/kg), and medetomidine (Domitor, 0.5 mg/kg). After induction of general anesthesia, mice were placed in a stereotactic frame (Model 900LS, David Kopf Instruments) equipped with mouth and ear bars, and located in a sterile procedure area. Depth of anesthesia was monitored by pinching of the rear foot and by observation of the respiratory pattern. Body temperature was closely monitored throughout the procedure, and kept constant at ∼37°C by the use of a heating mat and a DC temperature controller in conjunction with a rectal temperature probe (FHC).

The skin over the injection site was shaved and an incision was made, after which a small hole of ∼0.5 mm diameter was drilled into the skull with a 0.4 mm drill bit. Each mouse was injected with 20–100 nl of AAV1.Syn.GCaMP6m.WPRE.SV40 (Penn Vector Core; Chen et al., 2013) either into the right IC (Fig. 1) or auditory cortex, using a pulled glass pipette in conjunction with a custom-made pressure injection system. Injections into the IC were targeted to a position ∼0.9 mm lateral of the midline and ∼0.7 mm posterior to the transverse sinus. Injections into the auditory cortex were intended to transfect large populations of neurons in the primary auditory areas, which appear to contain most of the corticocollicular projection neurons (Hofstetter and Ehret, 1992; Bajo and Moore, 2005). They were made in two positions separated rostrocaudally by 0.5–1.0 mm and were centered on a spot ∼2.7 mm caudal of bregma and 0.2–0.4 mm below the dorsal edge of the temporal muscle. This typically resulted in transfection of cortical neurons over an area of at least 0.5 mm (mediolateral) × 1.0 mm (rostrocaudal).

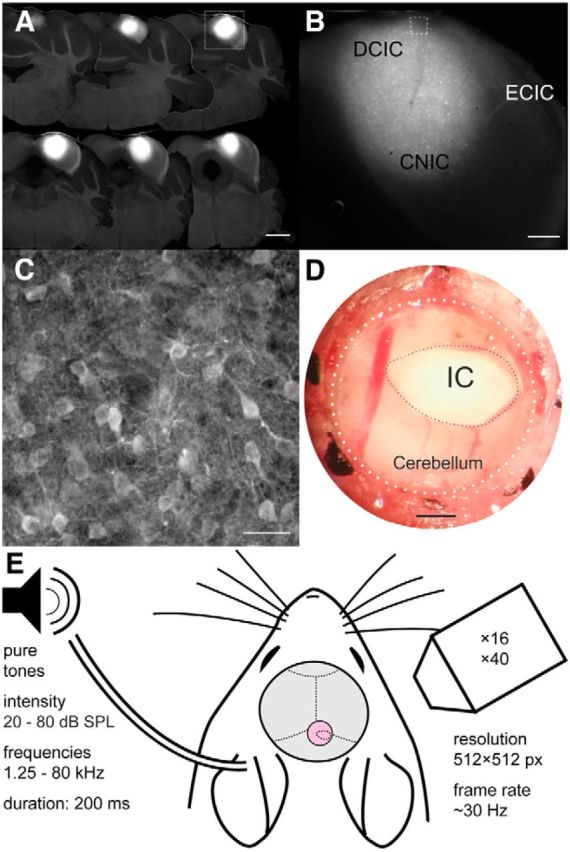

Figure 1.

GCaMP6m transduction of IC neurons and experimental setup. A, Coronal sections at 150 μm intervals showing widespread transduction of neurons throughout most of the dorsal parts of the IC. Scale bar, 1 mm. B, Higher-magnification image of one of the sections (A, white box) with the approximate locations of the DCIC, CNIC, and external cortex of the IC (ECIC) marked. Scale bar, 300 μm. C, Higher-magnification image (B, white box) showing individual IC cell bodies. Scale bar, 25 μm. D, Photograph of glass window (outlined by dotted lines) inserted into the skull over the IC. Scale bar, 500 μm. E, Experimental setup used for sound delivery and two-photon calcium imaging.

The skin was then sutured and general anesthesia was reversed with an intraperitoneal injection of naloxone (1.2 mg/kg), flumazenil (Anexate, 0.5 mg/kg), and atipamezol (Antisedan, 2.5 mg/kg). Buprenorphine (Vetergesic, 1 ml/kg) and enrofloxacine (Baytril, 2 ml/kg) were injected postoperatively as analgesic and antibiotic, respectively, and again 24 h later.

Imaging preparation.

The imaging experiments were performed 3–8 weeks after making the virus injection. To increase the stability of the IC imaging preparation, and to avoid the need to align data obtained over several sessions, all recordings were performed under anesthesia in a single imaging session. The mice were premedicated with dexamethasone (4 mg/kg) and atropine (0.5 ml/kg), and general anesthesia was induced with ketamine (100 mg/kg, Vetalar) and medetomidine (140 μg/kg). Ketamine (50 mg/kg/h) and medetomidine (0.07 mg/kg/h) were regularly topped up at ∼30 min intervals to maintain a stable level of anesthesia throughout the experiment. The mouse was placed in a stereotaxic frame and body temperature was kept constant at ∼37°C. Both eyes were covered with eye ointment (Maxitrol, Alcon) to prevent corneal desiccation during the experiment. A circular craniotomy was made over the right IC and a circular cover glass of 2.5 mm diameter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was placed onto the IC and secured in place to the surrounding skull with glue (UltraGel, Pattex). A small steel bar with two screw holes was glued onto the skull overlying the left cerebral hemisphere. Dental cement was used to create a small water basin around the craniotomy so that the objective could stay immersed in water during imaging. The mouse was then placed on a custom-made stage, its head fixed to the stage using the steel bar, and the stage placed inside a sound-attenuated imaging chamber.

Imaging.

Image acquisition was performed using a commercial two-photon laser-scanning microscope (B-Scope, Thor Labs). Excitation light (930 nm) came from a SpectraPhysics Mai-Tai eHP laser fitted with a DeepSee prechirp unit (70 fs pulse width, 80 MHz repetition rate). The beam was directed into a Conoptics modulator (laser power, as measured under the objective, varied from 10 to 50 mW) and scanned onto the brain with an 8 kHz resonant scanner (X) and a galvanometric scan mirror (Y). The resonant scanner was used in bidirectional mode, enabling the acquisition of 512 × 512 pixel frames at a rate of ∼30 Hz. Emitted photons were guided through a 525/50 filter onto GaAsP photomultipliers (Hamamatsu). ScanImage (http://scanimage.org) was used to control the microscope. Cell body imaging was performed with a 16×/0.80W LWD immersion objective (Nikon), whereas imaging of axon terminals was performed using a 40×/0.80 NIR Apo immersion objective (Nikon).

Stimulus presentation.

A thin silicone tube coupled to an electrostatic speaker (EC1, Tucker-Davis Technologies) was placed near the entrance of the mouse's left ear canal to deliver sounds during the experiment. These drivers were calibrated using a GRAS 40DP microphone coupled to the tube to ensure a flat (±3 dB) response at all presented frequencies (1.25 to 80 kHz). Ambient noise was kept low by keeping the laser's power supply in a separate room. Sound generated by the resonant scanner was <40 dB SPL near the mouse's head. Stimuli were generated with an RZ6 processor (Tucker-Davis Technologies) and controlled through custom-written MATLAB (MathWorks) code. To measure neuronal sound frequency sensitivity, we presented pure tones of 200 ms duration with 5 ms raised cosine onset and offset ramps that varied randomly in frequency (from 1.25 to 80 kHz in 1/4 octave steps) and level (in 20 dB steps from 20 to 80 dB SPL based on measurements taken at the entrance to the ear canal in a mouse cadaver). They were presented at a rate of ∼0.66 Hz (1 every 45 frames) and each frequency-level combination was presented nine times. These 900 stimuli were presented in blocks of 300.

Histology.

At the end of the experiment, the mouse was killed and perfused transcardially, first with PBS and then with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The relevant parts of the fixed brains were sectioned in the coronal plane at a thickness of 150 μm and images were taken with a Leica DMR upright fluorescence microscope, a Leica TCS SP5 X confocal microscope or the two-photon microscope. Images were processed offline using ImageJ (NIH).

Data analysis.

Data analysis was performed in MATLAB. Image stacks were registered to a 50-frame average using efficient subpixel registration methods (Guizar-Sicairos et al., 2008) to correct for x–y motion. Regions-of-interest (ROIs) corresponding to cell somata were determined manually on the basis of frame averages and inspection of movies of calcium activity, and all pixels within each ROI were averaged to give a single time course (ΔF/F). Neuropil correction was performed according to previously published methods using a contamination ratio, r, of 0.6 (Kerlin et al., 2010). The signal was also high-pass filtered at a cutoff frequency of 0.03 Hz to remove slow fluctuations in the signal. The first 15 frames (∼500 ms) following stimulus onset were defined as the response window and a single-trial response was defined as the average ΔF/F within that window. Neurons were included for analysis only if they exhibited a statistically significant difference in response among the 100 frequency-level combinations (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.001). Threshold was defined as the lowest level that exhibited a statistically significant difference among the 25 frequencies (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.01). For each neuron a matrix of the averaged responses to different frequency-level combinations was constructed, with different levels arranged in rows and different frequencies arranged in columns. This matrix was then smoothed across frequencies using a three point wide running average. Best frequency (BF) was defined as the sound frequency associated with the highest response averaged across all sound levels. This measure of frequency preference is considered to produce more orderly tonotopic maps (Hackett et al., 2011) than the characteristic frequency, which traditionally, has been more popular in descriptions of tonotopy and is the frequency to which the neuron is most responsive at its threshold. In our IC calcium imaging data, BF and characteristic frequency were highly correlated and produced similar tonotopic maps. The same appears to apply to data obtained from electrophysiological recordings in mouse auditory cortex (Guo et al., 2012; Joachimsthaler et al., 2014).

To further quantify these responses, each matrix was first normalized to a range of values from 0 (minimum response) to 1 (maximum response) and responses below the half-maximum were discarded. The remaining area was defined as the frequency response area (FRA). If more than one area of contiguous frequency-level combinations remained, the largest one was defined as the FRA. The shape of the FRA was scored as unclassifiable if it did not extend below the highest sound level tested. If the FRA increased in width from its threshold to 80 dB SPL by more than one of the tested frequency values (i.e., by >0.25 octaves), it was classified as V-shaped. Where this was not the case, FRAs were considered to be I-shaped if the largest response occurred at 80 dB SPL and O-shaped if the largest response occurred at a lower level. This classification procedure was automated and the results visually inspected. BWmax was defined as the maximum FRA width at any level. BW20 was defined as the width 20 dB above the threshold level.

To determine whether the neurons' BFs varied along a particular axis within the brain we collapsed, for each animal separately, all ROIs onto the same horizontal plane. We then correlated the BFs with their position on a series of axes spanning 360° at 1° intervals. The axis associated with the strongest positive correlation was taken as the direction of the tonotopic gradient. In the animal that showed two opposing gradients, we estimated the direction of each gradient by measuring the correlation only along the first half of the axes; the directions that corresponded to the two peaks in the resulting correlation function were chosen in this case.

In electrophysiological experiments in larger animals, such as the cat, a change in frequency selectivity can be used as an indicator for entry into the CNIC (Merzenich and Reid, 1974; Aitkin et al., 1975). Visual inspection of 3D plots of our imaging data also strongly suggested that the DCIC and CNIC of the mouse can be distinguished on the basis of the neurons' frequency preferences. To objectively assign neurons into each region of the IC, we made use of a support vector machine (SVM; svmtrain and svmclassify functions in MATLAB) that was trained to classify neurons based on their BF and that of the neighboring neurons. We trained the SVM on neurons from two distinct imaging areas from an experiment in which we were able to image a large population of neurons at different depths within the IC. One area was identified as belonging putatively to the DCIC and the other as belonging to the CNIC. Using different pairs of training areas yielded very similar classification results. Similar results were also achieved with K-means, an alternative classifier, which is not trained and is therefore purely data-driven.

For statistical comparisons, parametric (paired and independent t test) or nonparametric (Wilcoxon signed rank test and Mann–Whitney U test) tests were used depending on the normality of distributions (Shapiro–Wilk test). Data are reported as mean ± SD unless stated otherwise.

Imaging of corticocollicular axon terminals.

ROI definition was performed using a custom-written script implemented in MATLAB. Initially, each 512 × 512 pixel imaging area was parcellated into overlapping 8 × 8 pixel image patches. Next, a set of descriptors was calculated for each image patch. The descriptors used, “Histograms of Oriented Gradients” (HOG; Dalal and Briggs, 2005), were extracted separately from each of the image patches and used as features for subsequent classification. After pretraining using manually annotated data, an SVM then used the HOG features of each image patch to determine whether it contained a bouton. The subset without boutons was discarded, whereas those classified as containing boutons were processed further. To draw the ROI masks for each image patch containing a bouton, a region-growing algorithm (Nixon, 2012) was applied to each patch individually. The seed pixel for the region-growing algorithm was selected using a two-step procedure. First, a “circular Hough transform” (“imfindcircles” MATLAB function) was applied to each image patch containing a bouton and a circle was drawn around the bouton. The brightest pixel within the circle was then used as a seed. After region growing, morphological erosion (Nixon, 2012) was applied to each image patch, enhancing separation of overlapping bouton ROI masks. Finally, image patches were recombined into a single image containing all ROI masks.

When imaging far away from labeled cell bodies, as in the case of corticocollicular axons, contamination of bouton responses from neuropil is minimal (Glickfeld et al., 2013). A correction procedure was therefore not applied. All other aspects of the analysis of the bouton data were the same as for the cell body data.

Results

In vivo two-photon calcium imaging in the inferior colliculus

We injected an adeno-associated virus carrying the calcium indicator GCaMP6m into the IC of 14 mice (Fig. 1). These injections were aimed to transfect neurons in the most dorsal, optically accessible region of the IC (Fig. 1A–C). Using two-photon imaging, we recorded neuronal calcium signals in planes of 200 × 200 μm or 250 × 250 μm up to 300–400 μm below the brain's surface through a window inserted into the skull (Fig. 1D,E). This approach enabled us to characterize the frequency sensitivity of up to dozens of neurons simultaneously (Fig. 2A–F) and up to hundreds of neurons per animal.

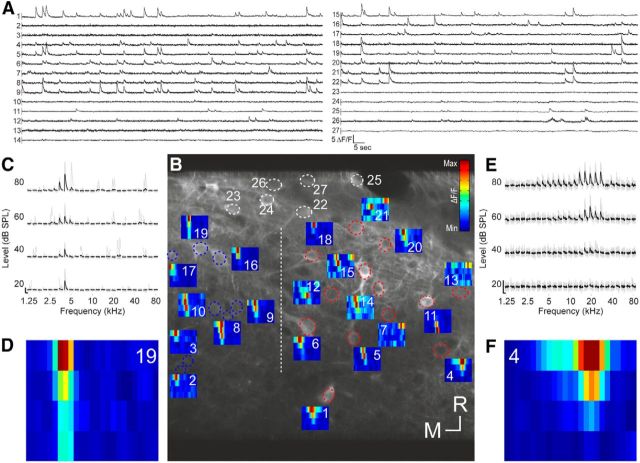

Figure 2.

Tone-evoked calcium responses of IC neurons in one imaging area. A, Fluorescence traces of all 27 neurons that were identified in this imaging area. B, Micrograph of the imaging area (200 × 200 μm) with ROIs drawn as dotted ellipsoids. ROIs marked in white indicate nonresponsive neurons. All other ROIs are color-coded according to the results of a SVM classification (see main text; blue, CNIC; red, DCIC). All CNIC neurons were found to the left of the dashed vertical line, all DCIC neurons were found to the right of the line. FRAs are depicted next to each responsive neuron. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, Fluorescence traces of neuron 19 ordered according to sound frequency and level. The nine traces associated with the nine repeats of each stimulus are plotted in gray. The average calcium signals are plotted in black. Scale bars indicate 2 ΔF/F and 1 s, respectively. D, FRA corresponding to C. E, F, Fluorescence traces and FRA for neuron 4, plotted as in C and D. R, Rostral; M, medial.

Distinguishing between the central nucleus and dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus

To study the functional organization of the dorsal mouse IC, we calculated the BF, the frequency which evoked the strongest average response across all sound levels, for each of the 1948 neurons and plotted its anatomical location color-coded according to its frequency preference. Figure 3A shows the anatomical location and BF of 322 neurons that were imaged in one animal. This revealed two distinct populations of neurons occupying different anatomical locations within the IC. Along the entire dorsal border of the imaged space, we found a thin layer of neurons that exhibited a preference for, mostly, midrange frequencies. The region just below this layer was occupied by a very different, fairly homogeneous population of neurons that almost exclusively preferred very low frequencies.

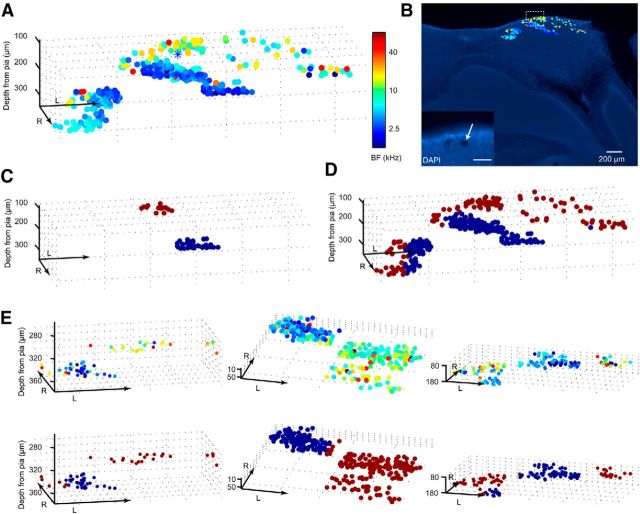

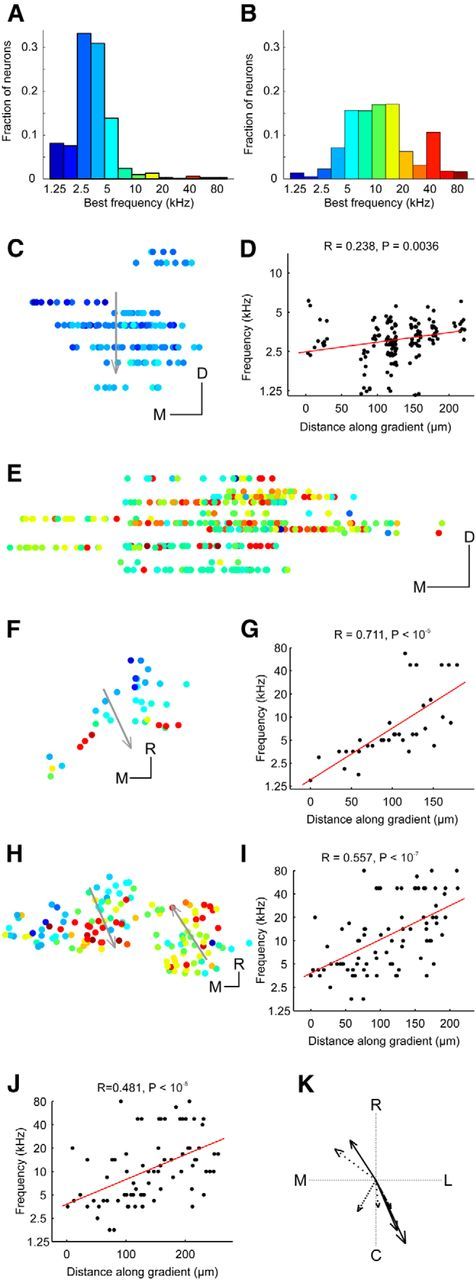

Figure 3.

Functional distribution of BFs within the IC. A, The relative spatial locations of 322 tone-responsive neurons from one animal were reconstructed in 3D space and color-coded according to each neuron's BF. Blue asterisk marks the coordinates of a laser ablation made at the end of this experiment. B, DAPI staining of the histological section that includes the site of the laser lesion (see inset). Scale bar, 50 μm. All neurons from A are superimposed onto this section, color-coded according to their BFs. C, Two representative imaging areas from this animal, one putatively DCIC (dark red), the other putatively CNIC (blue), were used to train a SVM. D, Using this SVM to classify the rest of the neurons from this animal segregates the data into putative DCIC (dark red) and CNIC (blue) areas. E, The same SVM classifier constructed using data from this animal was also used on all other animals. Representative examples from three other animals show the spatial distribution of neurons' BFs (top) and the results of the SVM classification (bottom). R, rostral; L, lateral. Axis arrow length, 200 μm. “Depth from pia” indicates the depth in micrometers relative to the tip of the IC. Note that due to the curvature of the IC the actual distance to the pia may be smaller for imaging areas at some x–y distance away from the tip.

Given what we know from mapping studies performed in other species (Winer and Schreiner, 2005), it seemed reasonable to conclude that the more dorsal and more heterogeneous population represents the DCIC and the more ventral, almost exclusively low-frequency preferring population represents the CNIC. On this basis, however, the DCIC is surprisingly thin, because the border with the CNIC lies barely >100 μm below the surface of the midbrain. In addition to carefully measuring the imaging depth relative to the pia mater, at the end of this experiment we marked one of the positions we had imaged by briefly increasing the laser power to induce a small lesion. This subsequently allowed us to register the imaged cell population on a histological section of the midbrain, thereby confirming the location of the putative DCIC neurons just below the surface of the IC (Fig. 3B).

Classification of neurons into the central nucleus and dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus

Before analyzing the data any further, we classified each neuron as belonging either to the DCIC or CNIC. To do this in an objective fashion, we used a supervised learning model (SVM classifier) to assign neurons to the DCIC or the CNIC. We first trained the model on two imaging areas from the animal whose complete dataset is illustrated in Figure 3A,B, a dorsal one that we considered to lie in the DCIC, and a more ventral one that we assumed to be located in the CNIC (Fig. 3C). We fed the SVM two pieces of information about each neuron: The BF of each neuron and the average BF within a sphere of 50 μm. We then used the SVM to classify all neurons imaged in this animal. Figure 3D shows the result of this classification. The same classifier was also applied to the other animals in our dataset, and three more examples are illustrated in Figure 3E. In each case, the putative DCIC and CNIC neuron populations were spatially segregated in different parts of IC that were broadly consistent with the relative location of these nuclei in other species.

Best frequency distributions in the central nucleus and dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus

The BF distribution for the putative CNIC dataset is shown in Figure 4A. In accordance with the known tonotopic organization of the CNIC, in which low sound frequencies are represented dorsally and high frequencies ventrally, our calcium imaging data, which were restricted to the most superficial region, revealed that most neurons preferred low-frequency tones. In contrast, we found that the majority of the neurons assigned to the DCIC had BFs between ∼5 and 20 kHz (Fig. 4B), with an additional peak in the ultrasonic range at ∼40 kHz. This overrepresentation of ultrasonic frequencies was only evident in four of the animals in the dataset, suggesting that these high-frequency neurons might cluster in a particular part of the DCIC, which was only imaged in some cases. Evidence for such a clustering of neurons with ultrasonic BFs within individual animals, however, was not observed.

Figure 4.

Tonotopic arrangement in the DCIC and upper CNIC. A, Histogram of BFs for upper CNIC neurons. B, Histogram of BFs for DCIC neurons. C, Location of upper CNIC neurons in one example animal color-coded by BF and collapsed onto the same coronal plane. D, BF plotted against distance along the dorsoventral axis indicated by the arrow in C. To improve visibility data points have been jittered in the x and y dimension by up to 15 μm and 0.125 octaves, respectively. Red line shows linear fit to nonjittered data. Four outliers with BFs of >10 kHz were excluded from C and D. E, Location of DCIC neurons in one example animal color-coded by BF and collapsed onto the same coronal plane to show variation in BF with depth. F, Location of DCIC neurons from one example animal color-coded by BF and collapsed onto the same horizontal plane. G, BFs plotted against distance along the tonotopic axis indicated by the arrow in F. H, Location of DCIC neurons from another example animal color-coded by BF and collapsed onto the same horizontal plane. I, BFs plotted against distance along the tonotopic axis indicated by the left arrow in H. J, BFs versus the distance along the tonotopic axis indicated by the right arrow in H. K, Directions of tonotopic gradients found in the DCIC of different animals (in one case, shown in H, two opposing frequency gradients were found). The arrow length is proportional to the R value of the projection. The line style indicates the P index (not corrected for multiple comparisons): solid (p < 10−5), dashed (p < 10−4), dotted (p < 0.001), and sparsely dotted (p < 0.01). C, Caudal; R, rostral; L, lateral; M, medial. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Tonotopic organization within the central nucleus and dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus

In most animals, imaging planes at similar x-y coordinates were obtained only over a small z-range. In one animal, however, we were able to image several planes over a few hundred micrometers of depth at similar x–y coordinates within the CNIC. These data revealed the presence of a significant low-to-high-frequency gradient, with a slope of 2.55 octaves per mm, running from dorsal to ventral (Fig. 4C,D), confirming that the CNIC is highly ordered even at this fine spatial scale. Nevertheless, the BFs of neurons within the same field of view (250 by 250 μm) can span a range of ≥1 octave, indicating that substantial local variability in frequency selectivity can exist. The cotuning (Issa et al., 2014), defined as the median SD of BF across neurons in the same field-of-view (a lower value indicates greater similarity among the BFs), was 0.424 in this animal. Across all animals in our dataset, the cotuning for all fields of view containing at least 10 neurons in the CNIC was 0.727 (± 0.43).

Much less is known about the tonotopic organization in the DCIC (Winer and Schreiner, 2005), especially in the mouse, where mapping studies have found mostly low-frequency neurons below the surface of the IC (Stiebler and Ehret, 1985; Willott, 1986; Romand and Ehret, 1990; Portfors et al., 2011; Ito et al., 2014), suggesting that the tonotopic organization of the CNIC simply continues into the DCIC. Given how thin the DCIC is it was usually not possible to image in the same x–y position of this region at several z levels. In one animal, we were able to image in similar x–y positions of the putative DCIC over several z levels spanning a range of ∼100 μm. This showed no evidence of any organization within the z-dimension (Fig. 4E). We therefore disregarded the z-dimension and, for each animal in turn, collapsed all neurons onto the same horizontal plane. To determine whether frequency selectivity varies along any particular axis within this plane, we then correlated the neurons' BFs with their position on a series of axes spanning 360°. The axis associated with the strongest positive correlation was taken as the direction of the tonotopic gradient. In 6 of 14 animals, we found evidence of a relationship between BF and neuron location. Data from two animals are illustrated in Figures 4F,G, and H–J, respectively, and the gradient directions for all six animals are indicated by the arrows in Figure 4K. Most gradients (n = 5) ran in a roughly rostral (low-frequency) to caudal (high-frequency) direction. Two others ran in an almost opposite, caudolateral to rostromedial direction, suggesting that the DCIC may contain two frequency representations. Indeed, in one animal (Fig. 4H–J), we found evidence of a frequency reversal in the distribution of BFs; this animal therefore provided two of the gradients illustrated in Figure 4K. Across all animals, the cotuning for all fields-of-view with at least 10 neurons in the DCIC was 1.185 (± 0.39), which indicated more BF heterogeneity than among neurons in the CNIC (t test, p < 10−4).

Comparison of receptive field properties between the central nucleus and dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus

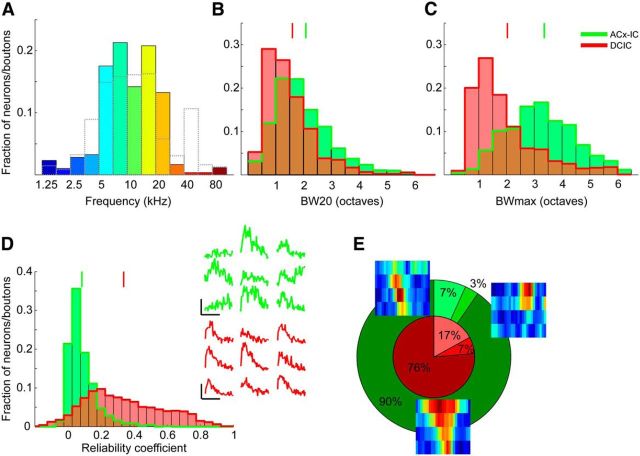

We first estimated the proportion of the 1297 putative DCIC and 651 CNIC neurons that responded to tones. Because a nonresponding neuron could not be classified as belonging to either region, we considered only the imaging areas in which all responding neurons were assigned exclusively to either the DCIC or the CNIC and assumed that the nonresponding neurons in the same imaging area also belonged to that part of the IC. The mean proportion of responsive neurons in the DCIC was estimated to be 39.5% (±24.4%), significantly lower than the proportion of responsive neurons in the CNIC (56.0 ± 23.3%, Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.0273). Both numbers are substantially higher than the proportions of responsive neurons we tend to see when imaging in the auditory cortex using the same experimental setup (data not shown).

Neurons in the DCIC and CNIC also differed in the width of their receptive fields. The mean BW20 was 1.60 (± 0.90) octaves for the DCIC and 1.24 (± 0.64) octaves for the CNIC (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 10−14; Fig. 5A). A similar difference was observed when we compared the mean BWmax, which was 2.03 (± 1.18) octaves for the DCIC and 1.55 (± 0.79) for the CNIC (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 10−17; Fig. 5B). However, bandwidth varies with BF, and in our dataset tended to be higher for the mid-range frequencies that most DCIC neurons preferred. Consequently, the difference in bandwidth between the two regions of the IC may, at least in part, be due to differences in BF. When we matched for BF, however, by restricting the analysis to neurons with BFs in the lower three octaves of the tested frequency range, binning all neurons into six half-octave wide bins according to their BFs and calculating bandwidths separately for each bin, we found that DCIC receptive fields were still consistently broader across frequencies (Figs. 5A,B, insets), but the difference in BW20 and BWmax was reduced substantially (mean BW20 = 1.45 ± 0.13 vs 1.23 ± 0.13, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.062; mean BWmax = 1.79 ± 0.28 vs 1.53 ± 0.31, paired t test, p = 0.0009).

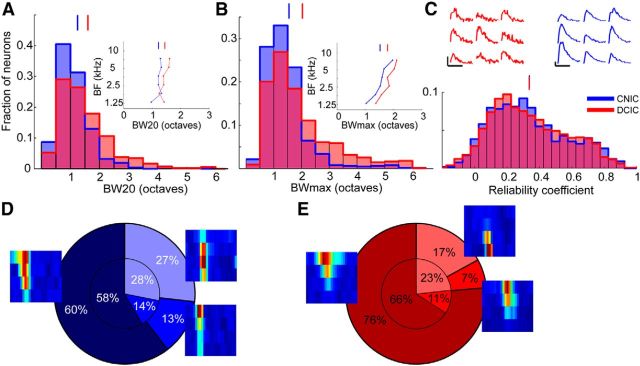

Figure 5.

Receptive field properties of DCIC and CNIC neurons. A, Histogram of BW20. Inset, The mean BW20 as a function of the neurons' BF. B, Histogram of BWmax. Inset, The mean BWmax as a function of the neurons' BF. C, Histogram of reliability coefficients. Upper fluorescence traces (red) show the responses evoked by nine presentations of the best stimulus for a DCIC neuron (same as in Fig. 2E,F). Reliability coefficient = 0.671. Upper fluorescence traces (blue) show the responses evoked by nine presentations of the best stimulus for a CNIC neuron (same as in Fig. 2C,D). Reliability coefficient = 0.740. D, Pie chart of FRA shapes of CNIC neurons. The slices indicate (clockwise) the proportion of O-shaped, I-shaped, and V-shaped FRAs. The small pie chart indicates the proportions of FRA shapes for neurons with BFs of ≤8.4 kHz. The proportions were calculated separately for half-octave wide BF bins and then averaged. E, Same as D for DCIC neurons. Examples for each type of FRA are also plotted next to the corresponding region of the pie charts. Vertical lines above histograms indicate means.

Approximately 25% of the neurons imaged in both regions responded at the lowest sound level tested (20 dB SPL), indicating that they may have had lower thresholds. Within the range of tested levels, we found that CNIC neurons had lower mean thresholds (43.09 ± 18.6 dB SPL) than DCIC neurons (49.54 ± 22.54 dB SPL, Mann–Whitney U test, p < 10−7). This difference remained after matching for BF (43.61 ± 2.45 dB SPL vs 48.05 ± 5.23 dB SPL, paired t test, p = 0.0593). Overall, DCIC neurons showed slightly stronger calcium responses than those in the CNIC. The mean of the maximum ΔF/F (for any of the frequency-level combinations) was 0.84 (± 0.67) for DCIC neurons versus 0.78 (± 0.66) for CNIC neurons (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.0011). The mean maximum response after correcting for BF was, however, higher among CNIC neurons, although the difference was not statistically significant (0.73 ± 0.17 vs 0.83 ± 0.13, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.56). Significantly more CNIC neurons (37.3%; 243/651) had nonmonotonic, peaked rate-level functions than in the DCIC (17.6%; 228/1297; χ2 test, p < 10−21). This difference was reduced when it was calculated separately for the different BF bins, but still present at all BFs and statistically significant (24 ± 10% vs 37 ± 10%, paired t test, p = 0.004).

To assess response reliability, we measured the similarity between a neuron's responses to each of the nine presentations of its best stimulus (the frequency-level combination that evoked the strongest average response) by calculating the average correlation coefficient for all pairwise combinations of the nine responses (Fig. 5C, top) and termed this the reliability coefficient. Here, response was defined as the entire 45-frame trace snippet poststimulus onset. We found no difference between DCIC and CNIC in the mean reliability coefficient (0.34 ± 0.23 vs 0.34 ± 0.24, Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.977; Fig. 5C). However, when matched for BF, the CNIC neurons were found to respond with slightly higher reliability (0.30 ± 0.05 vs 0.37 ± 0.04, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.031).

Finally, we determined whether the shapes of the DCIC and CNIC FRAs differed. Inspection of the FRAs from a single imaging area revealed that they come in a variety of shapes (Fig. 2). Although recent evidence suggests that receptive field shapes in the IC do not fall into discrete classes (Palmer et al., 2013, but see, Egorova et al., 2001; Portfors et al., 2011 for mouse-specific studies), categorizing them can be helpful in determining whether the FRAs of neurons in one brain area differ from those in another. We therefore classified them as V-shaped, I-shaped, or O-shaped (see Materials and Methods for criteria). In both IC regions, most FRAs were V-shaped rather than I- or O-shaped (Fig. 5D,E, large pie charts), but the proportion of V-shaped FRAs was significantly higher in the DCIC (76%; 708/927 neurons; Fig. 5E) than in the CNIC (60%; 345/571 neurons; Fig. 5D; χ2 test, p < 10−10). However, when calculating the proportion of shapes separately for different BF bins, the difference in the mean proportion of V-shaped FRAs between DCIC and CNIC was much smaller and not statistically significant (66 ± 17% vs 58 ± 15%, paired t test, p = 0.096; Fig. 5D,E, small pie charts).

Corticocollicular projections

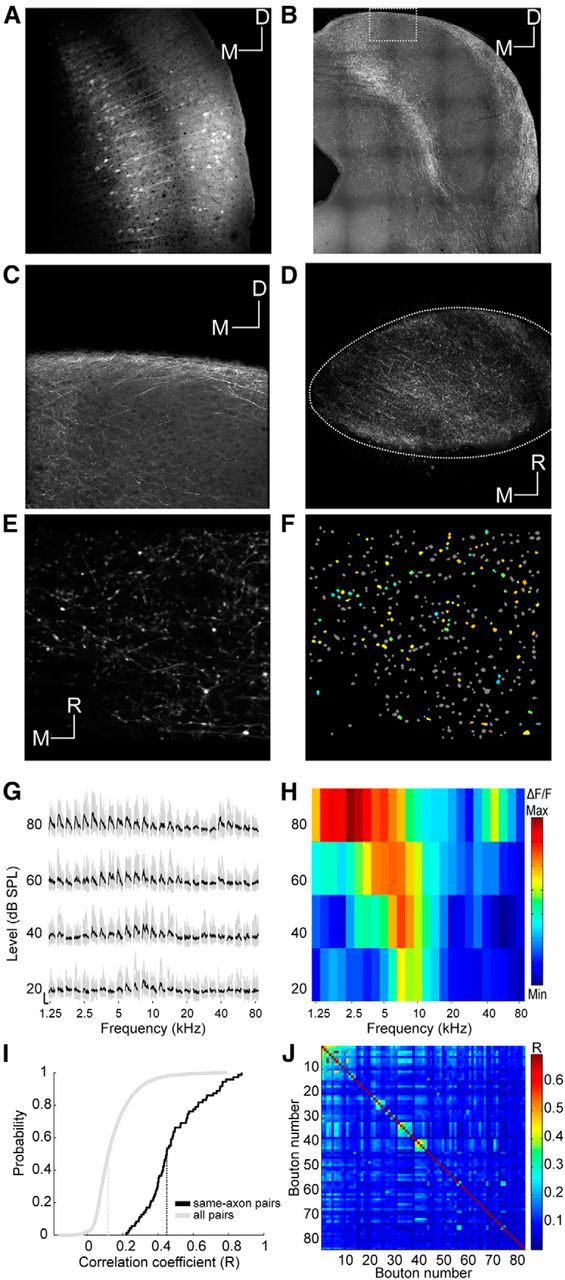

To investigate the response properties of corticocollicular axons, we transfected neurons in the auditory cortex (Fig. 6A) of 10 mice with the same genetically encoded calcium indicator used for transfecting IC neurons and then imaged their terminals in the dorsal IC. Figure 6B shows a coronal section through the IC of one of these animals. The corticocollicular axons gather in the outer regions of the IC and only few axons travel to the central nucleus. The labeling is at its thickest in the dorsomedial and ventrolateral part of the IC, whereas in the central and lateral parts of the dorsal IC the axons extend barely more than a few tens of micrometers below the surface (Fig. 6C). This pattern of labeling suggests that, in the mouse, the vast majority of projections from the auditory cortex terminate within the IC's shell regions, which comprise the DCIC and the external nucleus. Indeed, it is notable how similar the distribution of corticocollicular labeling in the dorsal IC (Fig. 6B,C) is to the region identified by the SVM as DCIC (Fig. 3). Viewing the corticocollicular axons from above reveals that they form a thick meshwork that covers the entire IC (Fig. 6D). At the level of magnification used for calcium imaging, the density of the corticocollicular axons can be seen even more clearly (Fig. 6E), and at this magnification we were able to identify individual axon terminals. Putative boutons were identified using an automated procedure (see Materials and Methods). In an imaging area of 100 by 100 μm, we typically identified hundreds of putative boutons (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6.

Imaging corticocollicular projections. A, Coronal section through the auditory cortex showing neurons transfected with GCaMP6m. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, Coronal section through the IC showing corticocollicular axons in this animal. Scale bar, 200 μm. C, Magnified section from B. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Large-scale in vivo view from above of corticocollicular axons and terminals. Scale bar, 100 μm. E, Example imaging area. Scale bar, 10 μm. F, Same imaging area as in E with nonresponsive ROIs indicated in gray and responsive ROIs color-coded according to BF. G, Example traces of a corticocollicular bouton response ordered according to frequency and level. The nine traces associated with the nine repeats of a particular stimulus are plotted in gray. The average trace is plotted in black. Scale bars: 1 ΔF/F and 1 s, respectively. H, FRA corresponding to G. I, Cumulative distributions of correlation coefficients between fluorescence traces of pairs of boutons. The median (dotted vertical line) correlation coefficient for all pairs of responding boutons in the dataset is close to zero (gray), suggesting that nonconnected pairs dominate. The median correlation coefficient for pairs of boutons from the same axon is much higher (black). Pairs of boutons belonging to the same axon were identified by visual inspection of structural images such as that shown in E. J, Correlation coefficient matrix of all boutons in one imaging area. Correlated boutons were assigned to clusters of terminals likely belonging to the same axon/neuron (Petreanu et al., 2012) to estimate the number of distinct axons per imaging area. The criterion used for assigning boutons to a cluster was an R value of at least 0.25, which is equivalent to p = 0.05 on the “same-axon pairs” distribution shown in I. D, Dorsal; M, medial; R, rostral.

The response properties of these corticocollicular afferents were characterized using the same stimuli as described before (Fig. 6G,H). Despite their density, the number of responsive boutons tended to be low. The mean number of responsive boutons per imaging area was 21.6 (± 19.43, the maximum was 91), and the total number was 1381. This is equivalent to only ∼8% of the putative boutons and much lower than the proportion of responsive DCIC neurons. The proportion of responsive corticocollicular terminals was also several times lower than that typically observed among auditory thalamocortical terminals using the same stimuli and experimental setup (Vasquez-Lopez et al., 2014), indicating that the sparseness of these responses is not due to limitations of the two-photon imaging method. By analyzing the correlations between the fluorescence traces of different boutons, we found that those identified visually as belonging to the same axon (and thus, the same neuron) had much higher correlation coefficients than the overall population (Fig. 6I). By applying that information to a clustering procedure (Petreanu et al., 2012; Fig. 6J), we estimated that the number of functionally distinct axons within an imaging area of 100 by 100 μm is in the order of 10–15 (median = 12 ± 12.01).

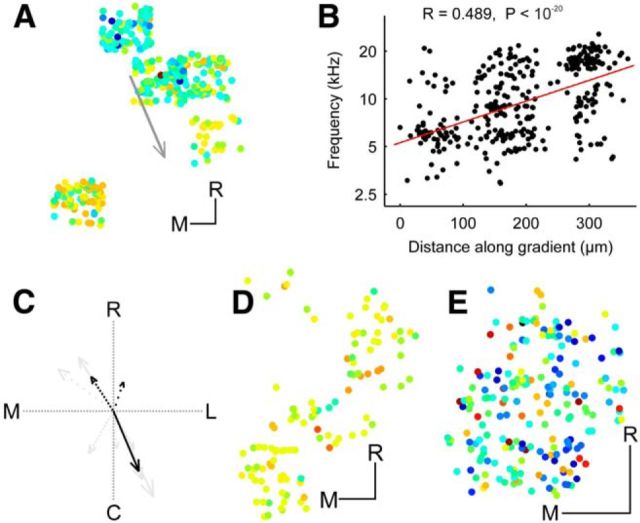

Our two-photon calcium imaging data provided evidence for tonotopic order in the corticocollicular projection. Thus, in three of the 10 animals, we found evidence of a relationship between bouton location and BF. Data from the animal with the strongest indication for a tonotopic gradient is shown in Figure 7A,B. Interestingly, the direction of the gradient was almost identical to the direction of the strongest gradients observed among the DCIC neurons (Fig. 7C). This was not observed in all the mice imaged, however, and Figure 7D,E show data from two example animals in which the imaged corticocollicular axon terminals lacked any apparent order in the distribution of their BFs.

Figure 7.

Tonotopic organization of corticocollicular boutons. A, Location of corticocollicular boutons from one example animal color-coded by best frequency (BF) and collapsed onto the horizontal plane. B, BFs of the boutons plotted against distance along the tonotopic axis indicated by the arrow in A. To improve visibility, data points were jittered in the y dimension by up to 0.125 octaves. C, Three of 10 animals showed evidence of a relationship between BF and bouton location. Directions of gradients (black) plotted on top of DCIC gradients (gray) from Figure 4K. The arrow length is proportional to the R value of the projection. The line style indicates the P index (not corrected for multiple comparisons): solid (p < 10−5), dashed (p < 10−4), dotted (p < 0.001), and sparsely dotted (p < 0.01). D, E, Location of corticocollicular boutons color-coded by BF and collapsed onto the same horizontal plane for two other example animals that did not show evidence for tonotopic order. M, Medial; R, rostral. Scale bars, 50 μm.

As in the DCIC, the range of sound frequencies most strongly represented by the corticocollicular axon terminals was ∼5 to 20 kHz (Fig. 8A). However, we did not observe the same second peak in the BF distribution in the ultrasonic range that we found for the DCIC neurons. We again found that ∼25% of the terminals responded at 20 dB SPL, the lowest sound level tested. Within the range of tested values, the mean threshold was 51.23 (± 21.28) dB SPL, which, although slightly higher, did not differ from the average for DCIC neurons (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.0611). With a mean BW20 of 2.08 (± 1.03) octaves and BWmax of 3.36 (± 1.22) octaves, the descending axon terminals were much more broadly tuned than the DCIC neurons (Fig. 8B,C; Mann–Whitney U test, p < 10−34 and p < 10−156, respectively). Just under one-third (30.5%, 421/1381) of the boutons had peaked response-level functions, which is significantly higher than the proportion of nonmonotonic response-level functions among DCIC neurons (χ2 test, p < 10−14). Apart from the fact that the proportion of responsive boutons was quite low, those that did respond did so in a very unreliable fashion (Fig. 8D, upper response traces), which might be expected of cortical neurons (Rothschild et al., 2010, compare their Fig. 3D). The mean reliability coefficient (0.084 ± 0.085) was much lower than that measured for the DCIC neurons (Fig. 8D; Mann–Whitney U test, p < 10−218). The FRAs were almost exclusively V-shaped (90%, 1243/1381), which means that the proportion of this FRA shape is significantly higher than among DCIC neurons (Fig. 8E; χ2 test, p < 10−18).

Figure 8.

Response properties of corticocollicular boutons. A, Histogram of BFs. Gray broken lines show histogram of BFs of DCIC neurons (from Fig. 4B). B, Histogram of BW20. Results for DCIC neurons are replotted in red (from Fig. 5A). C, Histogram of BWmax. Results for DCIC neurons are replotted in red. (from Fig. 5B). D, Histogram of reliability coefficients. Results for DCIC neurons are replotted in red (from Fig. 5C). Green traces show the responses evoked by nine presentations of the best stimulus of the bouton whose traces and FRA are shown in Figure 6G,H. Reliability coefficient = 0.163. Red traces show the responses evoked by nine presentations of the best stimulus for a DCIC neuron (replotted from Fig. 5C). Reliability coefficient = 0.671. E, Pie chart showing relative proportions of FRA shapes. The slices indicate (clockwise) the proportion of O-shaped, I-shaped, and V-shaped FRAs, together with representative examples of each FRA type. The small pie chart indicates the proportions of FRA shapes for DCIC neurons (from Fig. 5E). Vertical lines above histograms indicate means.

Discussion

Using two-photon calcium imaging, we characterized the frequency selectivity of neurons in the most dorsal regions of the mouse IC. By sampling neurons at a much greater spatial resolution than possible in electrophysiological mapping experiments (Stiebler and Ehret, 1985; Willott, 1986; Romand and Ehret, 1990; Portfors et al., 2011), our results show that this brain region houses two spatially and physiologically distinct populations of neurons. A thin sheet of neurons tuned mostly to medium and high frequencies lies beneath the surface of the IC, which most likely corresponds to the DCIC. Ventral to this region, and often barely >100 μm below the pial surface, we encountered a separate population of mostly low-frequency neurons with slightly sharper tuning and more reliable responses that appear to form the upper part of the CNIC. Furthermore, using the opportunity provided by this method to image the activity of labeled axons, we characterized the frequency selectivity of corticocollicular terminal boutons and showed that this projection predominantly targets the region identified here as the DCIC as well as other parts of the IC shell.

Anatomical considerations

Meininger et al. (1986) proposed that, as in other species, the mouse IC can be divided cytoarchitecturally into a central nucleus and, among other shell structures, a dorsal cortex. They described the DCIC as a four-layered structure occupying the most dorsal 300–500 μm of the IC. In contrast, our functional imaging data suggest that the CNIC extends well into this uppermost region of the IC. Although apparently inconsistent with the anatomical parcellation of the mouse IC, our results do account for why electrophysiological mapping studies in this species have consistently reported that the tonotopic map of the CNIC extends to the dorsal tip of the IC (Stiebler and Ehret, 1985; Willott, 1986; Romand and Ehret, 1990; Portfors et al., 2011). Given how thin the DCIC appears to be, a relatively coarse electrophysiological mapping approach might easily miss it. Moreover, our imaging data clearly refute the idea that the DCIC is simply a functional extension of the CNIC (Willott, 2001).

Frequency representation and tonotopic organization

Although the limited BF distribution obtained for the CNIC reflects the fact that we sampled neurons to a maximum depth of ∼300 μm and therefore from its dorsal low-frequency region only, the BFs of putative DCIC neurons covered a much greater portion of the mouse's hearing range. Most DCIC BFs were between ∼5 and 20 kHz with a peak near 15 kHz where the mouse is most sensitive (Zheng et al., 1999; Koay et al., 2002). This contrasts with earlier electrophysiological recordings (Stiebler and Ehret, 1985; Willott, 1986; Romand and Ehret, 1990; Portfors et al., 2011) and a recent imaging study (Ito et al., 2014), which found an overrepresentation of low-BF neurons in the dorsal IC, a result that would be expected if the most dorsal part of the CNIC had (at least partially) been sampled in those studies. We found that the distribution of BFs among the corticocollicular terminals matched that of the DCIC neurons, but with a smaller ultrasonic representation. This is consistent with evidence that few neurons in the auditory cortex of C57BL/6 mice are tuned to ultrasonic frequencies (Hackett et al., 2011; Martin del Campo et al., 2012; Moore and Wehr, 2013). The paucity of such neurons might reflect high-frequency hearing loss, which this strain is prone to, or the lack of involvement of the ultrasonic field in the corticocollicular labeling observed here.

It is well established that the CNIC shows a tonotopic progression from low to high frequencies that runs approximately dorsoventrally. Although we were only able to image neurons in its most dorsal region, the tonotopic organization of the CNIC was evident in our data. Furthermore, the slope of the measured gradient is very similar to what has been measured electrophysiologically (Romand and Ehret, 1990, Portfors et al., 2011). Our cotuning measurements indicate that there may be more BF similarity among neighboring CNIC neurons than in auditory cortex, as measured using two-photon calcium imaging of layer 2/3 neurons (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010; Rothschild et al., 2010), although a more recent study is inconsistent with this (Issa et al., 2014).

Whether neurons in the DCIC are also arranged according to their BFs is much less clear (Winer and Schreiner, 2005). That the DCIC might be tonotopically organized is implied by the topographic organization of the corticocollicular projection (Diamond et al., 1968; Andersen et al., 1980; Herbert et al., 1991; Bajo et al., 2007). A recent single-photon calcium imaging study in BALB/c mice found some evidence of a frequency gradient in the medial portion of the dorsal IC (Ito et al., 2014). Our results also suggest that there is some tonotopic order in the DCIC as several animals exhibited a systematic relationship between BF and neuron location. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of BFs of the corticocollicular terminals was consistent with that of the DCIC neurons. However, there was some variation between animals in the direction of the frequency gradients, and in one case, a reversal in direction was observed, suggesting that the DCIC might contain more than one representation of the cochlea rather than a continuous tonotopic gradient as is seen in the CNIC.

Response properties of inferior collicular neurons and corticocollicular terminals

Electrophysiological recordings have shown that CNIC neurons typically exhibit robust tone-evoked responses and sharp frequency tuning. Given the difficulty in defining the extent of the DCIC, it is not surprising that much less is known about the physiology of its neurons. This is particularly the case in mice, where the only previous studies have used whole-cell recordings to characterize some of the physiological properties and connectivity of DCIC neurons (Geis et al., 2011; Geis and Borst, 2013a,b). Neurons in the shell regions of the IC appear to be less selective for sound frequency than those in the CNIC (Aitkin et al., 1975), and more extensive differences might be expected given differences in their inputs (Coleman and Clerici, 1987; Oliver, 2005). However, although DCIC neurons were indeed more broadly tuned for sound frequency than CNIC neurons, this difference was modest, particularly after matching for BF differences between the two datasets.

The response properties of corticocollicular boutons were quite distinct from those of the putative DCIC neurons, even though they are located in very similar regions of the IC. Tone-responsive corticocollicular terminals were quite sparse and they responded in a very unreliable fashion. Their FRAs were also much broader and more likely to be V-shaped than those of DCIC neurons. The broad tuning of the corticocollicular terminals is consistent with that of the intrinsic-bursting layer 5 cortical neurons that project to the IC and the high spontaneous activity of these neurons might account for the seemingly inconsistent responses of the boutons (Sun et al., 2013). Although it is possible that anesthesia might have contributed to the noisy and unreliable responses of the corticocollicular boutons, intrinsic-bursting layer 5 cortical neurons are thought to be driven by direct thalamic input (Sun et al., 2013). Consequently, the effects of anesthesia on the activity of the corticocollicular projection neurons may not be as pronounced as on other cortical neurons. Anesthesia may also affect the activity of IC neurons (Gruters and Groh, 2012). However, given the robustness of frequency tuning reported across anesthetic states, even in mouse cortex (Guo et al., 2012), this is unlikely to have had a substantial effect on the findings reported here.

Our results suggest that it is unlikely that DCIC neurons, at least under anesthesia, derive their receptive field properties from the auditory cortex. Instead, it seems more likely that “driver” input to the DCIC originates from brainstem nuclei that send sparse projections to the DCIC (Coleman and Clerici, 1987, Oliver, 2005) or potentially from other IC regions such as the CNIC (Coleman and Clerici, 1987). We therefore propose that the extensive descending cortical input to the DCIC has a modulatory influence on the neurons found there. Similarly, driver synapses from the retina to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) are far outnumbered by corticothalamic modulatory synapses onto the same dLGN relay cells, but it is the retinal ganglion cells, rather than the cortical inputs, that impart their receptive field structure on the dLGN neurons (Sherman, 2007).

The functional consequences of manipulating the activity of auditory corticocollicular neurons have been extensively studied (Xiong et al., 2009; Bajo et al., 2010; Anderson and Malmierca, 2013). These experiments have, however, focused almost exclusively on the interaction between neurons in the cortex and the CNIC, even though corticocollicular neurons primarily target the dorsal and lateral cortices of the IC (Bajo and King, 2012). The availability of methods for imaging presynaptic and postsynaptic signals in the DCIC provides a unique opportunity for investigating how the cortex modulates the subcortical processing of acoustic information, both during normal behavior and following different forms of adaptation (Bajo et al., 2010; Anderson and Malmierca, 2013).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust through a Principal Research Fellowship (WT07650AIA) to A.J.K. and a PhD Studentship to Y.W. (WT102373/Z/13/Z), and by a German National Academic Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes) scholarship and PhD funding through the Medical Research Council and a University College War Memorial Studentship to O.B. We thank S. Hofer, T. Mrsic-Flogel, L. Cossell, S. Vasquez-Lopez, V. Bajo, and A. Hoerder-Suabedissen for helpful discussions and advice.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed.

References

- Ahmadlou M, Heimel JA. Preference for concentric orientations in the mouse superior colliculus. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Webster WR, Veale JL, Crosby DC. Inferior colliculus: I. Comparison of response properties of neurons in central, pericentral, and external nuclei of adult cat. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:1196–1207. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen mouse brain atlas. 2015. Available at http://mouse.brain-map.org/

- Andersen RA, Snyder RL, Merzenich MM. The topographic organization of corticocollicular projections from physiologically identified loci in the AI, AII, and anterior auditory cortical fields of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:479–494. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Malmierca MS. The effect of auditory cortex deactivation on stimulus-specific adaptation in the inferior colliculus of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:52–62. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, King AJ. Cortical modulation of auditory processing in the midbrain. Front Neural Circuits. 2012;6:114. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, Moore DR. Descending projections from the auditory cortex to the inferior colliculus in the gerbil, Meriones unguiculatus. J Comp Neurol. 2005;486:101–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, Nodal FR, Bizley JK, Moore DR, King AJ. The ferret auditory cortex: descending projections to the inferior colliculus. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:475–491. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, Nodal FR, Moore DR, King AJ. The descending corticocollicular pathway mediates learning-induced auditory plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:253–260. doi: 10.1038/nn.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Shamma SA, Kanold PO. Dichotomy of functional organization in the mouse auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nn.2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JR, Clerici WJ. Sources of projections to subdivisions of the inferior colliculus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;262:215–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal N, Triggs B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In: Schmid C, Soatto S, Tomasi C, editors. International conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR '05) San Diego: IEEE Computer Society; 2005. pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT, Jones EG, Powell TP. The association connections of the auditory cortex of the cat. Brain Res. 1968;11:560–579. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorova M, Ehret G, Vartanian I, Esser KH. Frequency response areas of neurons in the mouse inferior colliculus. I. Threshold and tuning characteristics. Exp Brain Res. 2001;140:145–161. doi: 10.1007/s002210100786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg EH, Meister M. Orientation columns in the mouse superior colliculus. Nature. 2015;519:229–232. doi: 10.1038/nature14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis HR, Borst JG. Large GABAergic neurons form a distinct subclass within the mouse dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus with respect to intrinsic properties, synaptic inputs, sound responses, and projections. J Comp Neurol. 2013a;521:189–202. doi: 10.1002/cne.23170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis HR, Borst JG. Intracellular responses to frequency modulated tones in the dorsal cortex of the mouse inferior colliculus. Front Neural Circuits. 2013b;7:7. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis HR, van der Heijden M, Borst JG. Subcortical input heterogeneity in the mouse inferior colliculus. J Physiol. 2011;589:3955–3967. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickfeld LL, Andermann ML, Bonin V, Reid RC. Cortico-cortical projections in mouse visual cortex are functionally target specific. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:219–226. doi: 10.1038/nn.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruters KG, Groh JM. Sounds and beyond: multisensory and other non-auditory signals in the inferior colliculus. Front Neural Circuits. 2012;6:96. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizar-Sicairos M, Thurman ST, Fienup JR. Efficient subpixel image registration algorithms. Opt Lett. 2008;33:156–158. doi: 10.1364/OL.33.000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Chambers AR, Darrow KN, Hancock KE, Shinn-Cunningham BG, Polley DB. Robustness of cortical topography across fields, laminae, anesthetic states, and neurophysiological signal types. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9159–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0065-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett TA, Barkat TR, O'Brien BM, Hensch TK, Polley DB. Linking topography to tonotopy in the mouse auditory thalamocortical circuit. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2983–2995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5333-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert H, Aschoff A, Ostwald J. Topography of projections from the auditory cortex to the inferior colliculus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304:103–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter KM, Ehret G. The auditory cortex of the mouse: connections of the ultrasonic field. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:370–386. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrizbegovic E, Bogdanovic N, Canlon B. Sound stimulation increases calcium-binding protein immunoreactivity in the inferior colliculus in mice. Neurosci Lett. 1999;259:49–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JB, Haeffele BD, Agarwal A, Bergles DE, Young ED, Yue DT. Multiscale optical Ca2+ imaging of tonal organization in mouse auditory cortex. Neuron. 2014;83:944–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Hirose J, Murase K, Ikeda H. Determining auditory-evoked activities from multiple cells in layer 1 of the dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus of mice by in vivo calcium imaging. Brain Res. 2014;1590:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachimsthaler B, Uhlmann M, Miller F, Ehret G, Kurt S. Quantitative analysis of neuronal response properties in primary and higher-order auditory cortical fields of awake house mice (Mus musculus) Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:904–918. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold PO, Nelken I, Polley DB. Local versus global scales of organization in auditory cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin AM, Andermann ML, Berezovskii VK, Reid RC. Broadly tuned response properties of diverse inhibitory neuron subtypes in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;67:858–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koay G, Heffner R, Heffner H. Behavioral audiograms of homozygous med(J) mutant mice with sodium channel deficiency and unaffected controls. Hear Res. 2002;171:111–118. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00492-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Izquierdo MA, Cristaudo S, Hernández O, Pérez-González D, Covey E, Oliver DL. A discontinuous tonotopic organization in the inferior colliculus of the rat. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4767–4776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0238-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin del Campo HN, Measor KR, Razak KA. Parvalbumin immunoreactivity in the auditory cortex of a mouse model of presbycusis. Hear Res. 2012;294:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger V, Pol D, Derer P. The inferior colliculus of the mouse: a Nissl and Golgi study. Neuroscience. 1986;17:1159–1179. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Reid MD. Representation of the cochlea within the inferior colliculus of the cat. Brain Res. 1974;77:397–415. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AK, Wehr M. Parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory interneurons in auditory cortex are well-tuned for frequency. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13713–13723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0663-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon M. Feature extraction and image processing for computer vision. Ed 3. London: Academic; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K, Chung S, Ch'ng YH, Kara P, Reid RC. Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature. 2005;433:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nature03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL. Neuronal organization in the inferior colliculus. In: Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The inferior colliculus. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 69–114. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR, Shackleton TM, Sumner CJ, Zobay O, Rees A. Classification of frequency response areas in the inferior colliculus reveals continua not discrete classes. J Physiol. 2013;591:4003–4025. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.255943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petreanu L, Gutnisky DA, Huber D, Xu NL, O'Connor DH, Tian L, Looger L, Svoboda K. Activity in motor-sensory projections reveals distributed coding in somatosensation. Nature. 2012;489:299–303. doi: 10.1038/nature11321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portfors CV, Mayko ZM, Jonson K, Cha GF, Roberts PD. Spatial organization of receptive fields in the auditory midbrain of awake mouse. Neuroscience. 2011;193:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romand R, Ehret G. Development of tonotopy in the inferior colliculus: I. Electrophysiological mapping in house mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;54:221–234. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90145-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild G, Mizrahi A. Global order and local disorder in brain maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:247–268. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild G, Nelken I, Mizrahi A. Functional organization and population dynamics in the mouse primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:353–360. doi: 10.1038/nn.2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Feliciano M, Mugnaini E. Distribution of descending projections from primary auditory neocortex to inferior colliculus mimics the topography of intracollicular projections. J Comp Neurol. 1996;371:15–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960715)371:1%3C15::AID-CNE2%3E3.0.CO%3B2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM. The thalamus is more than just a relay. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiebler I, Ehret G. Inferior colliculus of the house mouse: I. A quantitative study of tonotopic organization, frequency representation, and tone threshold distribution. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:65–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Tuning shifts of the auditory system by corticocortical and corticofugal projections and conditioning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:969–988. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YJ, Kim YJ, Ibrahim LA, Tao HW, Zhang LI. Synaptic mechanisms underlying functional dichotomy between intrinsic-bursting and regular-spiking neurons in auditory cortical layer 5. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5326–5339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4810-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez-Lopez S, Keating P, King AJ, Dahmen JC. Functional characterisation of thalamic input to the auditory cortex. ARO Abstr. 2014;37:PS-096. [Google Scholar]

- Willard FH, Ryugo DK. Anatomy of the central auditory system. In: Willott JF, editor. The auditory psychobiology of the mouse. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1983. pp. 201–304. [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF. Effect of aging, hearing loss, and anatomical location on thresholds of inferior colliculus neurons in C57BL/6 and CBA mice. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:391–408. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF. Handbook of mouse auditory research: from behavior to molecular biology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Urban GP. Response properties of neurons in nuclei of the mouse inferior colliculus. J Comp Physiol. 1978;127:175–184. doi: 10.1007/BF01352302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Schreiner CE. The inferior colliculus. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Larue DT, Diehl JJ, Hefti BJ. Auditory cortical projections to the cat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:147–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981019)400:2%3C147::AID-CNE1%3E3.0.CO%3B2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Yan J. The neurobiology of sound-specific auditory plasticity: a core neural circuit. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng QY, Johnson KR, Erway LC. Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res. 1999;130:94–107. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]