Abstract

Context:

Diet is proposed to contribute to androgen-related reproductive dysfunction.

Objective:

This study evaluated the association between dietary macronutrient intake, carbohydrate fraction intake, and overall diet quality on androgens and related hormones, including anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and insulin, in healthy, regularly menstruating women.

Design:

This was a prospective cohort study from 2005 and 2007.

Setting:

The study was conducted at the University at Buffalo, western New York State, USA.

Participants:

Participants were 259 eumenorrheic women without a self-reported history of infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or other endocrine disorder.

Main Outcome Measures:

A 24-hour dietary recall was administered 4 times per menstrual cycle, and hormones were measured 5 to 8 times per cycle for 1 (n = 9) or 2 (n = 250) cycles per woman (n = 509 cycles). Associations between the dietary intake of carbohydrates (starch, sugar, sucrose, and fiber), macronutrients, overall diet quality and hormones (insulin, AMH, and total and free testosterone), as well as the relationship of dietary intake with occurrences of high total testosterone combined with high AMH (fourth quartile of each), ie, the “PCOS-like phenotype,” were assessed.

Results:

No significant relationships were identified between dietary intake of carbohydrates, percent calories from any macronutrient or overall diet quality (ie, Mediterranean diet score) and relevant hormones (insulin, AMH, and total and free testosterone). Likewise, no significant relationships were identified between dietary factors and the occurrence of a subclinical PCOS-like phenotype.

Conclusions:

Despite evidence of a subclinical continuum of a PCOS-related phenotype of elevated androgens and AMH related to sporadic anovulation identified in previous studies, dietary carbohydrate and diet quality do not appear to relate to these subclinical endocrine characteristics in women without overt PCOS.

Lifestyle modifications, including dietary intervention, may improve the reproductive features affected by androgen-related anovulatory infertility, such as those in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (1, 2). Previous research has noted that a low-calorie diet led to a reduction in androgen levels along with weight loss in patients with PCOS, and, furthermore, patients who adopted a high-protein/low-glycemic load diet, rather than a conventional low-calorie diet, also attained a greater concomitant reduction in insulin resistance (3). Indeed, replacement of carbohydrate calories with unsaturated fat, for example, increased insulin sensitivity outside the context of PCOS (4). However, it is not clear whether dietary factors linked to insulin sensitivity, such as glycemic load, are involved in the etiology of PCOS or whether they are related to reproductive features in women without PCOS.

As currently defined, PCOS affects 15% to 20% of women and is marked by 2 of 3 characteristics including hyperandrogenism, irregular menstrual cycles, and polycystic-appearing ovaries on ultrasound (5). Previous research has demonstrated that women with PCOS are at greater risk for developing metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease and are frequently plagued by obesity and insulin resistance (5, 6). Our previous work described a subclinical continuum of the endocrine features of PCOS and identified a higher rate of sporadic anovulatory cycles in cycles with higher androgen and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) (a marker of ovarian follicle number) in normally menstruating, healthy women (7), as well as several dietary and metabolic factors potentially associated with sporadic anovulation (8–10).

Here, our aim was to investigate whether dietary intake in this population, with a particular emphasis on carbohydrate fractions, is associated with these PCOS-related endocrine features across the menstrual cycle, including testosterone, AMH, and fasting insulin, using dietary data measured by the gold standard of repeated 24-hour dietary recalls.

Materials and Methods

Participants and study design

The BioCycle Study was a prospective study to determine the association of oxidative stress with endogenous reproductive hormone levels and antioxidants across the menstrual cycle among healthy, premenopausal women aged 18 to 44 years (11). Full details of participant recruitment, data collection, participant characteristics, and clinic visit timing for the BioCycle Study have been described elsewhere (12, 13). Included here are the details relevant to the present investigation. Women who had menstrual cycles between 21 and 35 days for the preceding 6 months, a lack of pregnancy or postpartum state in the previous 6 months, and no known diagnosis of PCOS or other endocrine dysfunction (eg, diabetes, Cushing syndrome, or conditions of the adrenal glands, hypothalamus, or other organs) were included in the study (12). Furthermore, included women had not used hormonal contraceptive medication for at least 12 months (ie, Depo-Provera, Norplant, or intrauterine device) or 3 months for oral contraceptives or other hormone supplements (ie, patch or ring) before enrollment. Women were followed prospectively between 2005 and 2007 for 2 (n = 250) menstrual cycles, in addition to some participants who participated for 1 (n = 9) menstrual cycle; all 259 women were included in the current investigation. Participants were recruited through local advertisements and media and were provided modest compensation (12). The study was conducted at the University at Buffalo in New York State, under an Intramural Research Program contract from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The University at Buffalo Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study, and served as the Institutional Review Board designated by the National Institutes of Health under a reliance agreement. All participants provided written informed consent.

Women provided health and lifestyle information and underwent measurements of weight and height and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for determination of percent body fat (14). Fasting blood samples were collected between 7:00 and 8:30 am up to 8 times per menstrual cycle at study visits (94% completed ≥7 visits per cycle), corresponding to early menstruation, the midfollicular phase, 3 samples of peri-ovulation, and the early, mid, and late luteal phases. Study visits were timed to menstrual cycle phases using a calendar and Clearblue Easy home fertility monitors (Inverness Medical) (13).

Dietary assessments

Diet factors were measured using multiple 24-hour dietary recalls. Recalls were administered at the clinic visits 4 times during each cycle (87% of women completed 4 dietary recalls per cycle), corresponding to menstruation, the midfollicular phase, the estimated day of ovulation, and the midluteal phase, for a total of up to 8 dietary recalls per woman. Intakes (grams per day) of total carbohydrate, total sugars, sucrose, starch, and water-soluble dietary fiber were determined from the recall data using the Nutrition Data System for Research (version 2005; Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota) (15), and a Mediterranean diet score was calculated for each recall as described previously (16). The percent intake for each macronutrient was also determined as a proportion of total calories consumed from each carbohydrate, fat, and protein.

Biochemical analyses

Serum sample collection tubes remained at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes before being placed in a 4°C centrifuge at 1500 × g for 10 minutes. Serum aliquots were then collected and stored frozen at −80°C until the time of assay. Fasting insulin and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) were determined using a solid-phase competitive chemiluminescent enzymatic immunoassay (IMMULITE 2000; Specialty Laboratories, Inc). Albumin was measured by bromocresol purple methods and glucose by a hexokinase-based assay using a Beckman LX20 autoanalyzer. Coefficients of variation (CVs) were <10% for insulin and SHBG. AMH was analyzed using the original GEN II ELISA protocol (Beckman Coulter). All machine-observed concentrations were used without substitution of concentrations below the limits of detection to avoid biases (17). To maximize measurement precision of AMH, 6 of 46 batches/plates were recalibrated using a pooled standard curve (18), as indicated by improper calibration curves or out-of-range values for manufacturer-provided control samples (CV = 12%). The total testosterone concentration (nanograms per deciliter) was determined by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry employing a Shimadzu Prominence Liquid Chromatogram (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc) with an AB Sciex 5500 tandem mass spectrometer. Increased sensitivity was obtained by use of mobile phase B (100% acetonitrile) with a low standard of 4 ng/dL added to the standard curve; the interassay CV was 6.7%.

Free testosterone was calculated as 24.00314 × T/log10S − 0.0499 × T2 and free androgen index as 100 ×(T/S), where T is total testosterone in nanomoles per liter and S is SHBG in nanomoles per liter (19). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as (insulin [milli-international units per liter] × glucose [milligrams per deciliter])/405 (20, 21).

Statistical analyses

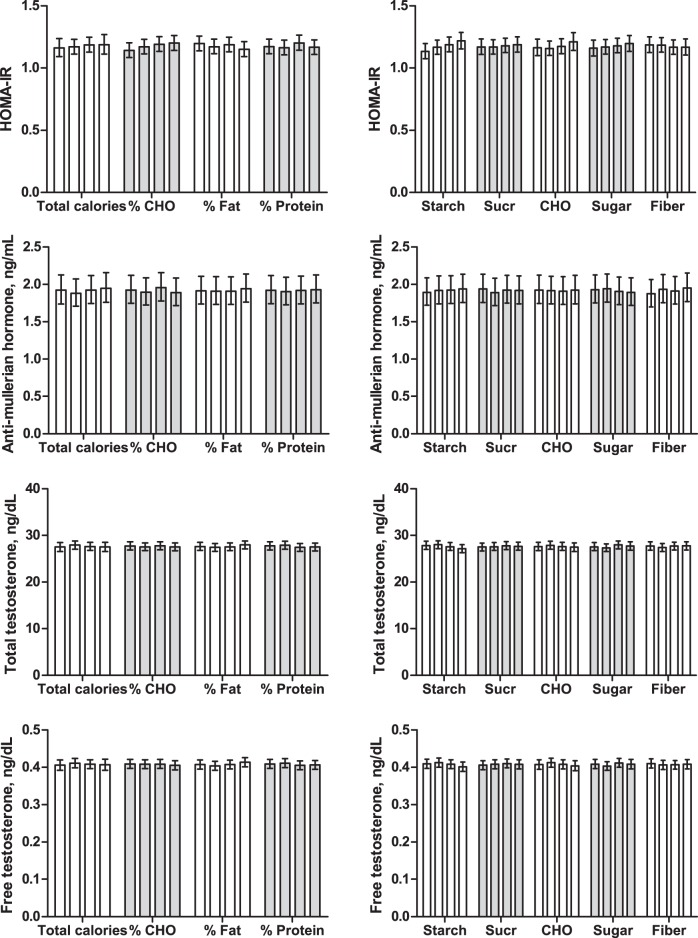

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline demographic, reproductive, and metabolic features of participants. Associations between dietary intake of overall macronutrients and carbohydrate fractions and hormones were determined using linear mixed models of log-transformed hormones. Models accounted for repeated measures within woman across both cycles and across days within each cycle. Geometric least squares means of log-transformed hormones adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), menstrual cycle phase, and total calorie consumption are presented (Figure 1). Covariates of age, BMI, and menstrual cycle phase were selected as confounders because of their potential association with both dietary intake and hormone outcomes. Models of individual dietary components (eg, starch) also included total calorie consumption to measure the effect of each dietary component independent of the level of calories consumed in the total diet. A mild PCOS-like phenotype was defined as a cycle having both an AMH and total testosterone concentration among the highest quartile for each at the menses visit (n = 53 cycles), as defined previously and previously associated with PCOS characteristics of increased acne and sporadic anovulation (7). To evaluate the relationships between dietary factors and occurrence of the mild PCOS-like phenotype (7), logistic regression using generalized linear mixed-effects models to account for repeated measures within woman were performed. Results are presented as the odds of a PCOS-like phenotype associated with a 1-unit increase in respective intakes, adjusted for age, BMI, and total calorie consumption (see Table 3). The logistic models were also repeated among overweight (n = 60 overweight only) and/or obese women (n = 25 obese only) only to better assess these relationships among non–normal weight women. Total energy substitution models of hormone and phenotype outcomes were also performed, including percent total calories from carbohydrate vs fat vs protein with appropriate adjustments for age, BMI, and menstrual cycle phase (menstrual cycle phase included in hormone but not phenotype models) as described above. One macronutrient was omitted from each model, repeating the analysis for all possible pairs of macronutrients to reflect the substitution of consuming calories from carbohydrate in place of fat (with the fat term omitted), or in place of protein, or consuming calories from fat in place of carbohydrate (with the carbohydrate term omitted), and so on (22).

Figure 1.

Metabolic and reproductive hormones across quartiles of dietary intake. Data are geometric means and 95% confidence intervals. Bars reflect the lowest to highest quartile of dietary intake, left to right within each diet factor. Actual ranges of intake by quartile are defined for each diet factor in Table 2. No significant differences across quartiles of dietary intake were detected for any hormone outcome. CHO, total carbohydrate; Sucr, sucrose; fiber, water-soluble dietary fiber; %, reflects percentage of total calories.

Table 3.

Odds of PCOS-Like Phenotype Per Unit Increase in Nutrient Intake

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| % calories from carbohydrate | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | .44 |

| % calories from fat | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.03 | .74 |

| % calories from protein | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.07 | .28 |

| Starch, g/d | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | .83 |

| Sucrose, g/d | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | .53 |

| Total carbohydrate, g/d | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | .62 |

| Total sugars, g/d | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | .93 |

| Water soluble dietary fiber, g/d | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.34 | .01 |

| Mediterranean diet score | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.11 | .44 |

Logistic regression using generalized linear mixed-effects models to account for repeated measures within woman was performed, adjusted for age, BMI, and total caloric intake. Results are presented as the odds of a PCOS-like phenotype associated with a 1-unit increase in respective intakes.

All hormone data were shifted to standardize the day of cycle for estimated time of ovulation and cycle phase, and missing hormone data were imputed as discussed previously (23). Specifically, days were aligned to ovulation, which was estimated based on the LH peak from the fertility monitor compared with the observed serum LH maximum and the first day of progesterone rise (23). All statistical analyses took multiple imputations into account using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants were overall healthy, young (average ± SD, 27.3 ± 8.2 years; range, 18–44 years), predominantly nonobese (24.1 ± 3.9 mg/kg2), Caucasian (59%), educated (87% with postsecondary education), and nonsmoking (86%) (Table 1). Dietary intake was variable with the middle 50% of participants' total carbohydrate intake (interquartile range) ranging from 146 to 248 g/d, corresponding to 43% to 59% of total calories consumed as carbohydrate. Quartiles of the overall cohort for each of the dietary variables of interest are defined (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Study Entry

| Characteristic | No. | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 259 | 27.3 (8.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 259 | 24.1 (3.9) |

| Body fat, % | 248 | 29.5 (6.0) |

| Race (C/AA/A) | 259 | 59/20/21 |

| Education, postsecondary | 259 | 87 |

| Current smokers | 259 | 4 |

| Nulliparous | 253 | 74 |

| Past use of hormonal contraception | 255 | 55 |

| Currently sexually activea | 192 | 70 |

| Age at menarche, y | 255 | 12.5 (1.2) |

| Usual menstrual bleeding, days | 239 | 5.1 (1.1) |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 257 | 87.2 (6.6) |

| TG, mg/dL | 257 | 59.2 (27.9) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 257 | 163.4 (29.0) |

| HDL, mg/dL | 257 | 50.1 (11.5) |

| LDL, mg/dL | 257 | 101.5 (25.7) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 257 | 4.0 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: A, Asian; AA, African American; C, Caucasian; TG, triglyceride; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Data are means (SD) or %; data reflect the baseline visit of the first menstrual cycle (study entry).

Percentage of those reporting any past sexual activity; n = 67 reported no (past or current) sexual activity.

Table 2.

Quartiles of the Overall Cohort for Each of the Dietary Variables of Interest

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % calories from carbohydrate | 6.2–42.6 | 42.6–50.9 | 50.9–58.8 | 58.8–89.0 |

| % calories from fat | 5.4–27.2 | 27.2–34.0 | 34.0–40.2 | 40.2–68.3 |

| % calories from protein | 3.5–12.1 | 12.1–15.1 | 15.1–18.4 | 18.4–41.7 |

| Starch, g/d | 0–62.6 | 62.6–87.0 | 87.0–116.5 | 116.5–571.2 |

| Sucrose, g/d | 0–16.6 | 16.6–31.2 | 31.3–50.2 | 50.2–326.1 |

| Total carbohydrate, g/d | 8.7–146.2 | 146.3–192.0 | 192.1–247.7 | 248.5–658.3 |

| Total sugars, g/d | 1.8–49.9 | 50.1–77.2 | 77.2–109.6 | 109.6–357.5 |

| Water soluble dietary fiber, g/d | 0.1–2.3 | 2.3–3.4 | 3.4–4.8 | 4.8–16.8 |

| Mediterranean diet score | 0–1 | 2–2 | 3–3 | 4–8 |

Diet and PCOS-like phenotype

No significant relationships were identified across quartiles of dietary intake of carbohydrates, percent calories from any macronutrient (Figure 1) or overall diet quality (ie, Mediterranean diet score), and relevant hormone outcomes (fasting insulin [data not shown], HOMA-IR, AMH, and total and free testosterone).

Likewise, no significant relationships were identified between dietary intake of carbohydrates, percent calories from any macronutrient or overall diet quality (ie, Mediterranean diet score), and the occurrence of a PCOS-like phenotype (defined as falling into the highest quartile for both testosterone and AMH) (7), with the exception of a higher odds of the PCOS-like phenotype with greater fiber intake (Table 3). Results were nearly identical when analysis was limited to overweight (n = 60 overweight only) and/or obese women (n = 25 obese only) only (data not shown).

Substitutions of calories from one macronutrient category for another (eg, percent calories from carbohydrate in place of fat, or carbohydrate in place of protein) also all produced null associations with hormones and the PCOS-like phenotype examined here (data not shown).

Discussion

Dietary intake was not related to the endocrine characteristics previously associated with a PCOS-like phenotype (7) in this population of healthy, predominately nonobese women. Results remained null for nearly all associations between carbohydrate intake and relevant hormone concentrations, including fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, AMH, and free and total testosterone throughout the menstrual cycle. Results remained null when also evaluated as the overall proportion of calories consumed from carbohydrate vs fat vs protein. Likewise, no associations were identified between dietary carbohydrate intake, with the exception of dietary fiber, and occurrences of a mild PCOS-like phenotype, defined here as having relatively elevated testosterone and AMH combined (7). Diet may be related to insulin resistance and obesity that are linked to PCOS in clinical cases, but the relationship between diet and insulin function, AMH, and/or testosterone is not evident in the range of hormones occurring in healthy, nonobese women.

Diet may affect reproductive function through myriad pathways and mechanisms (24). In particular, insulin resistance and obesity, conditions influenced by dietary intake (25–27), have been implicated in the pathophysiology of PCOS (28). Moreover, dietary interventions have been proposed to ameliorate specific components of PCOS, including general healthy diet and exercise to improve insulin sensitivity and restore ovulatory function (29), lower carbohydrate diet to improve hyperandrogenemia (30), and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation to reduce PCOS-related cardiovascular disease risk (31). Even normal-weight women with PCOS are reported to have lower insulin sensitivity than their BMI-matched non-PCOS counterparts (32) and to show improvement in symptoms with metformin (ie, “insulin sensitizer”) treatment (33). However, the interplay of reproductive steroid hormones, insulin resistance, obesity, and ovarian function is incompletely understood.

Others have indicated more recently, using different methods to assess insulin sensitivity and related glucose-insulin parameters (ie, intravenous glucose tolerance test with minimal model assessment), that metformin may exert its beneficial effects in women with PCOS through changes in glucose disposal independent of insulin (ie, glucose-mediated glucose disposal) and not through impacts on insulin sensitivity (34). Furthermore, the prevalence of obesity among women with PCOS is not different from that among the general population when an unselected population is assessed (35). Thus, greater referral or seeking of medical care may occur in women who are both obese and have PCOS characteristics, leading to greater identification of PCOS in obese, insulin-resistant women than in those without obesity. In agreement, others indicate evidence of 2 distinct phenotypes of PCOS, those with vs without obesity and insulin resistance (36).

Thus, in the current study in which no relationships were identified between key hormones previously described as a mild PCOS-like phenotype, diet was not relevant to an effect on metabolic and endocrinologic features related to the ovarian dysfunction of PCOS within a nonclinical range. Indeed, there was no association identified here between any dietary carbohydrate factors typically associated with promotion of insulin resistance and hormone concentrations in the highest quartile levels of both testosterone and AMH combined, an indicator from our previous study of a mild PCOS-like phenotype in the subclinical range (7). Such evidence may indicate that reported dietary patterns are a consequence of an aberrant insulin system in women already having PCOS and concomitant obesity, but perhaps not a cause of an insulin-driven PCOS etiology. It may also be that behavioral diet changes can affect the insulin-related component of PCOS in patients who are already insulin resistant, but not in women without overt insulin resistance, as dietary interventions from a lower carbohydrate diet to omega-3 fatty acid supplementation have been shown to bring about clinical improvements in PCOS characteristics in some studies of obese women (29–31). Indeed, the current study does not support a relationship between dietary patterns in healthy women with subclinical manifestations of an aberrant insulin, AMH, and testosterone milieu. Instead, our previous findings of a subclinical PCOS-related phenotype (7) may indicate a constitutional disposition that may not be influenced by excess carbohydrate or excess calorie intake, particularly outside the context of obesity and resultant insulin resistance.

An alternative explanation for the null association identified between dietary intake and hormone outcomes or a PCOS-related phenotype reported here may also be due to a relatively narrow range of hormone concentrations observed across this normal population, compared with a population with clinical disease, as wider variation in measurements may have been necessary to provide adequate power for detecting a small effect size, if such an effect existed. Likewise, more extreme levels of intake over time or randomizing participants to an extreme diet may be necessary to cause measurable changes in hormone outcomes that could not be detected in this observational cohort study conducted across a relatively short time window. The median level of carbohydrate intake observed here (51% of calories from carbohydrate) was similar to the 49% to 50% of calories consumed from carbohydrate observed contemporaneously in US women (37). In addition, the significant association observed between increased fiber intake and increased odds of the PCOS-like phenotype reflects our prior findings linking high fiber intake with higher odds of anovulation (9) but does not support the promotion of a PCOS phenotype through the dysregulation of glycemia and insulinemia.

The present study benefits from several advantages. First, multiple dietary recalls were applied and blood samples were collected at several visits, specifically timed to ovulation, through 2 consecutive menstrual cycles in a carefully selected population allowing thorough characterization of cyclic hormone patterns. Second, the participants in this study were not taking any hormonal medications (eg, contraceptive pills) that may disrupt the accurate measurement of testosterone and/or AMH concentrations. This study also overcomes common limitations in studies of testosterone in women by using highly sensitive assay methods (liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry) to measure testosterone. A limitation of our study is that we cannot rule out the effects of chronic, more extreme dietary intakes, or the effect of moderate or high intakes in a predominantly obese or insulin-resistant population, limiting the generalizability of our findings. We did conduct a sensitivity analysis, however, restricting our analyses to overweight and obese women (60 overweight and 25 obese), finding identical null results. Likewise, these findings should not be extrapolated to women with clinical PCOS.

Thus, although dietary interventions have been reported to be have an impact in managing PCOS in some studies, dietary intake in women without PCOS was not associated with PCOS-related hormones including testosterone, AMH, and insulin. Therefore, despite previous evidence of a subclinical continuum of a PCOS-related phenotype of elevated androgens and AMH related to sporadic anovulation, dietary carbohydrate and diet quality do not appear to relate to such subclinical characteristics. Whereas dietary interventions may still have promise in women with clinical PCOS, particularly those with features of insulin resistance and/or obesity, such intervention is not likely to improve reproductive function within the subclinical range of these features outside of the context of obesity. Thus, specific recommendations regarding dietary intake, particularly regarding carbohydrate intake, to prevent progression of PCOS in women with subclinical features may not be warranted, aside from general recommendations for a healthful diet that are universal in promoting overall health and preventing other chronic disease in women.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (Contract HHSN275200403394C and Contract HHSN275201100002I Task 1 HHSN27500001). The funding source had no role in the study design, data gathering, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit the report for publication.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- HOMA-IR

- homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- SHBG

- sex hormone–binding globulin.

References

- 1. Liepa GU, Sengupta A, Karsies D. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and other androgen excess-related conditions: can changes in dietary intake make a difference? Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mahoney D. Lifestyle modification intervention among infertile overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehrabani HH, Salehpour S, Amiri Z, Farahani SJ, Meyer BJ, Tahbaz F. Beneficial effects of a high-protein, low-glycemic-load hypocaloric diet in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled intervention study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gadgil MD, Appel LJ, Yeung E, Anderson CA, Sacks FM, Miller ER., 3rd The effects of carbohydrate, unsaturated fat, and protein intake on measures of insulin sensitivity: results from the OmniHeart trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1132–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2038–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sjaarda LA, Mumford SL, Kissell K, et al. Increased androgen, anti-Müllerian hormone, and sporadic anovulation in healthy, eumenorrheic women: a mild PCOS-like phenotype? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:2208–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mumford SL, Schisterman EF, Siega-Riz AM, et al. Cholesterol, endocrine and metabolic disturbances in sporadic anovulatory women with regular menstruation. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, et al. Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Chavarro JE, et al. The impact of dietary folate intake on reproductive function in premenopausal women: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schisterman EF, Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, et al. Influence of endogenous reproductive hormones on F2-isoprostane levels in premenopausal women: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:430–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wactawski-Wende J, Schisterman EF, Hovey KM, et al. BioCycle study: design of the longitudinal study of the oxidative stress and hormone variation during the menstrual cycle. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:171–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howards PP, Schisterman EF, Wactawski-Wende J, Reschke JE, Frazer AA, Hovey KM. Timing clinic visits to phases of the menstrual cycle by using a fertility monitor: the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yeung EH, Zhang C, Albert PS, et al. Adiposity and sex hormones across the menstrual cycle: the BioCycle Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schakel SF, Sievert YA, Buzzard IM. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J Am Diet Assoc. 1988;88:1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gaskins AJ, Rovner AJ, Mumford SL, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and plasma concentrations of lipid peroxidation in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1461–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guo Y, Harel O, Little RJ. How well quantified is the limit of quantification? Epidemiology. 2010;21:S10–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whitcomb BW, Perkins NJ, Albert PS, Schisterman EF. Treatment of batch in the detection, calibration, and quantification of immunoassays in large-scale epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S44–S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sartorius G, Ly LP, Sikaris K, McLachlan R, Handelsman DJ. Predictive accuracy and sources of variability in calculated free testosterone estimates. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bonora E, Targher G, Alberiche M, et al. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vaccaro O, Masulli M, Cuomo V, et al. Comparative evaluation of simple indices of insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2004;53:1522–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology, 2nd ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mumford SL, Schisterman EF, Gaskins AJ, et al. Realignment and multiple imputation of longitudinal data: an application to menstrual cycle data. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25:448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baird DT, Cnattingius S, Collins J, et al. Nutrition and reproduction in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ebbeling CB, Leidig MM, Feldman HA, Lovesky MM, Ludwig DS. Effects of a low-glycemic load vs low-fat diet in obese young adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2092–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Long-term effects of low glycemic index/load vs. high glycemic index/load diets on parameters of obesity and obesity-associated risks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dunaif A, Wu X, Lee A, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Defects in insulin receptor signaling in vivo in the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E392–E399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huber-Buchholz MM, Carey DG, Norman RJ. Restoration of reproductive potential by lifestyle modification in obese polycystic ovary syndrome: role of insulin sensitivity and luteinizing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1470–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gower BA, Chandler-Laney PC, Ovalle F, et al. Favourable metabolic effects of a eucaloric lower-carbohydrate diet in women with PCOS. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79:550–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cussons AJ, Watts GF, Mori TA, Stuckey BG. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation decreases liver fat content in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial employing proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3842–3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palomba S, Falbo A, Russo T, et al. Insulin sensitivity after metformin suspension in normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3128–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baillargeon JP, Jakubowicz DJ, Iuorno MJ, Jakubowicz S, Nestler JE. Effects of metformin and rosiglitazone, alone and in combination, in nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and normal indices of insulin sensitivity. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pau CT, Keefe C, Duran J, Welt CK. Metformin improves glucose effectiveness, not insulin sensitivity: predicting treatment response in women with polycystic ovary syndrome in an open-label, interventional study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:1870–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ezeh U, Yildiz BO, Azziz R. Referral bias in defining the phenotype and prevalence of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1088–E1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dale PO, Tanbo T, Vaaler S, Abyholm T. Body weight, hyperinsulinemia, and gonadotropin levels in the polycystic ovarian syndrome: evidence of two distinct populations. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]