Abstract

Context:

The significance of studies suggesting an increased risk of bone fragility fractures with hyponatremia through mechanisms of induced bone loss and increased falls has not been demonstrated in large patient populations with different types of hyponatremia.

Objective:

This matched case-control study evaluated the effect of hyponatremia on osteoporosis and fragility fractures in a patient population of more than 2.9 million.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

Osteoporosis (n = 30 517) and fragility fracture (n = 46 256) cases from the MedStar Health database were matched on age, sex, race, and patient record length with controls without osteoporosis (n = 30 517) and without fragility fractures (n = 46 256), respectively. Cases without matched controls or serum sodium (Na+) data or with Na+ with a same-day blood glucose greater than 200 mg/dL were excluded.

Main Outcome Measures:

Incidence of diagnosis of osteoporosis and fragility fractures of the upper or lower extremity, pelvis, and vertebrae were the outcome measures.

Results:

Multivariate conditional logistic regression models demonstrated that hyponatremia was associated with osteoporosis and/or fragility fractures, including chronic [osteoporosis: odds ratio (OR) 3.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.59–4.39; fracture: OR 4.61, 95% CI 4.15–5.11], recent (osteoporosis: OR 3.06, 95% CI 2.81–3.33; fracture: OR 3.05, 95% CI 2.83–3.29), and combined chronic and recent hyponatremia (osteoporosis: OR 12.09, 95% CI 9.34–15.66; fracture: OR 11.21, 95% CI 8.81–14.26). Odds of osteoporosis or fragility fracture increased incrementally with categorical decrease in median serum Na+.

Conclusions:

These analyses support the hypothesis that hyponatremia is a risk factor for osteoporosis and fracture. Additional studies are required to evaluate whether correction of hyponatremia will improve patient outcomes.

Hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte disorder seen in clinical practice (1), and there is accumulating evidence that even mild hyponatremia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (2–5). Determining whether hyponatremia is a cause of morbidity and mortality is an important question, both because drugs induce hyponatremia (eg, thiazides, antidepressants) and because treatments for hyponatremia are available (eg, vasopressin receptor antagonists) (6).

Classical physiology studies demonstrate that a large fraction of body sodium is stored in bone (7), suggesting that bone may serve as a potentially mobilizable sodium reservoir during periods of homeostatic stress. Animal model studies suggest that chronic hyponatremia can cause or accelerate osteoporosis, organ dysfunction, and senescence (8, 9). Also, at least two case-control studies and two cohort studies suggest an association between osteoporosis or fracture and hyponatremia (10–13), and a recent case report describes a patient with partial reversal of severe osteoporosis after correction of chronic hyponatremia (14). Furthermore, clinical studies indicate that acute hyponatremia can induce a broad spectrum of neurological manifestations, ranging from mild nonspecific symptoms to more significant disorders. The neurological dysfunctions associated with hyponatremia have been shown to include gait instability (15) and increased falls (16, 17), both of which could compound patient fracture risk.

To investigate the possibility that increased risks of osteoporosis and fractures represent potential mechanisms of increased morbidity and mortality in hyponatremic patients, we performed a matched case-control study. The primary aim of this study was to characterize and quantify the strength of the associations of osteoporosis and fragility fracture with hyponatremia while accounting for multiple clinical factors in a large combined in-patient and outpatient population. A secondary aim of the study was to characterize the association of chronic and recent hyponatremia with osteoporosis and fragility fractures to test the hypothesis that hyponatremia contributes to increased patient risk of fracture both acutely (by increasing risks of falls) and chronically (by inducing osteoporosis).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a matched case-control study within the MedStar Health institutions' pooled patient electronic health records database. Methods of obtaining deidentified patient data using the Explore application on the Explorys Inc platform have been described elsewhere (18). A brief synopsis of these methods is provided in the Supplemental Materials. This technology uses a server behind the firewall of participating MedStar Health institutions in the Maryland, Virginia, and greater Washington, DC, area to capture information from patients' in-patient and outpatient records, including admissions, discharges, transfers, surgical procedures, and historical records. There were more than 2.9 million unique patient records in the MedStar Health database available for query at the time of the study. The duration of the patient records under investigation extends from electronic health record implementation in the MedStar system in 2002 to the beginning of the present study in 2013; however, data entered retrospective of electronic record implementation date back as far as 1987 and were also included in the study. The study was approved by the MedStar Health Research Institutional Review Board; the requirement for informed consent was waived in view of the deidentified nature of the analyses.

Two groups of patients were selected as case subjects. The first group had at least one diagnosis of osteoporosis as defined by International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, code 733 for osteoporosis. The second group had at least one diagnosis of fragility fracture as defined by International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, codes for fracture of upper (810–819) or lower limb (820–829), pelvis (808), or vertebral column (805). Cases without matched controls on specified criteria (described below) were excluded. Patient cases and controls with no serum sodium concentration (Na+) in the database or with any serum Na+ with a same-day glucose greater than 200 mg/dL were excluded from the analysis.

Two control groups were selected. Each osteoporosis and fragility fracture case was matched separately on age at first encounter within 1 year, sex, race according to the categories listed in Tables 1 and 2 below, and duration of the patient record in the database (±1 mo) with one control without osteoporosis or without fragility fracture, respectively. Matching was performed with SAS 9.3 software using the Mayo Clinic gmatch general SAS macro. Consort diagrams of both the osteoporosis and fragility fracture subject selection and matching are provided in the Supplemental Materials (see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Osteoporosis Study Subjects and Unadjusted Odds Ratios

| Osteoporosis (n = 30 517) | No Osteoporosis (n = 30 517) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n, % | ||||

| Female | 26 932 (88.3) | 26 932 (88.3) | ||

| Male | 3585 (11.7) | 3585 (11.7) | ||

| Race, n, % | ||||

| Caucasian | 18 224 (59.7) | 18 224 (59.7) | ||

| African American | 8630 (28.3) | 8630 (28.3) | ||

| Unknown | 2568 (8.4) | 2568 (8.4) | ||

| Other | 1016 (3.3) | 1016 (3.3) | ||

| Asian | 61 (0.2) | 61 (0.2) | ||

| Native American or Alaskan | 15 (0.05) | 15 (0.05) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) | ||

| Multiracial | 2 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) | ||

| Age at first encounter, y, n, % | ||||

| <30 | 492 (1.6) | 492 (1.6) | ||

| ≥30 and <50 | 3632 (11.9) | 3632 (11.9) | ||

| ≥50 and <70 | 12 956 (42.5) | 12 956 (42.5) | ||

| ≥70 and <80 | 7356 (24.1) | 7356 (24.1) | ||

| ≥80 | 6081 (19.9) | 6081 (19.9) | ||

| Duration of the patient record in the database, mo, n, % | ||||

| <1 | 1669 (5.5) | 1668 (5.5) | ||

| ≥1 and <3 | 820 (2.7) | 822 (2.7) | ||

| ≥3 and <6 | 448 (1.5) | 447 (1.5) | ||

| ≥6 and <12 | 798 (2.6) | 796 (2.6) | ||

| ≥12 and <24 | 1821 (6.0) | 1824 (6.0) | ||

| ≥24 | 24 961 (81.7) | 24 960 (81.7) | ||

| Duration of encounter window, mo, n, % | ||||

| <1 | 5821 (19.1) | 5821 (19.1) | ||

| ≥1 and <3 | 2318 (7.6) | 2325 (7.6) | ||

| ≥3 and <6 | 1090 (3.6) | 1093 (3.6) | ||

| ≥6 and <12 | 1593 (5.2) | 1591 (5.2) | ||

| ≥12 and <24 | 2752 (9.0) | 2744 (9.0) | ||

| ≥24 | 16 943 (55.5) | 16 943 (55.5) | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.0 (7.8) | 28.3 (6.9) | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | <.001 |

| Imputed BMI, mean (SE)a | 26.7 (0.07) | 27.6 (0.05) | 0.98 (0.975–0.983) | <.0001 |

| Medication history, n, % | ||||

| Antipsychotic | 384 (1.3) | 177 (0.6) | 2.18 (1.83–2.61) | <.0001 |

| Estrogen | 279 (0.9) | 185 (0.6) | 1.52 (1.26–1.83) | <.0001 |

| Glucocorticoid | 1911 (6.3) | 1077 (3.5) | 1.87 (1.73–2.02) | <.0001 |

| NSAID | 1646 (5.4) | 1141 (3.7) | 1.49 (1.38–1.61) | <.0001 |

| Opiate | 3376 (11.1) | 1928 (6.3) | 1.90 (1.79–2.02) | <.0001 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 3591 (11.8) | 2328 (7.6) | 1.90 (1.79–2.02) | <.0001 |

| Progesterone | 180 (0.6) | 109 (0.4) | 1.66 (1.31–2.11) | <.0001 |

| Antiepileptic | 100 (0.3) | 37 (0.1) | 2.70 (1.85–3.94) | <.0001 |

| SSRI | 1352 (4.4) | 936 (3.1) | 1.48 (1.36–1.61) | <.0001 |

| Antidepressant | 306 (1.0) | 155 (0.5) | 1.99 (1.64–2.42) | <.0001 |

| Testosterone | 58 (0.2) | 11 (0.04) | 5.27 (2.77–10.05) | <.0001 |

| Thiazide | 2836 (9.3) | 2171 (7.1) | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | <.0001 |

| Loop diuretic | 1315 (4.3) | 944 (3.1) | 1.42 (1.30–1.55) | <.001 |

| Disease history, n, % | ||||

| Liver | 882 (2.9) | 621 (2.0) | 1.44 (1.30–1.60) | <.0001 |

| Heart failure | 2155 (7.1) | 2342 (7.7) | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) | .003 |

| Pulmonary | 6206 (20.3) | 5009 (16.4) | 1.32 (1.26–1.38) | <.0001 |

| Central nervous system | 4858 (15.9) | 3933 (12.9) | 1.31 (1.25–1.37) | <.0001 |

| Malignancy | 601 (2.0) | 492 (1.6) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | .001 |

| Behavioral history, n, % | ||||

| Tobacco use | 5356 (17.6) | 3876 (12.7) | 1.50 (1.44–1.58) | <.0001 |

| Alcohol use | 884 (2.9) | 652 (2.1) | 1.37 (1.24–1.52) | <.0001 |

| Hyponatremia exposure, n, % | ||||

| Prior | 4856 (15.9) | 4130 (13.5) | 1.23 (1.17–1.28) | <.0001 |

| Chronic or recent hyponatremia exposure, n, % | ||||

| Not chronic or recentb | 26 444 (86.7) | 29 080 (95.3) | Reference | Reference |

| Only chronicb | 1402 (4.6) | 481 (1.6) | 3.25 (2.92–3.62) | <.0001 |

| Only recentb | 1898 (6.2) | 889 (2.9) | 2.53 (2.32–2.77) | <.0001 |

| Chronic and recentb | 773 (2.5) | 67 (0.2) | 13.1 (10.1–16.9) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Missing BMI data for cases and controls were imputed from data of patients with BMI data available.

The ORs in these categories were generated from a single model. ORs need to be compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Fragility Fracture Study Subjects and Unadjusted ORs

| Fragility Fracture (n = 46 256) | No Fragility Fracture (n = 46 256) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n, % | ||||

| Female | 25 629 (55.4) | 25 629 (55.4) | ||

| Male | 20 627 (44.6) | 20 627 (44.6) | ||

| Race, n, % | ||||

| Caucasian | 25 266 (54.6) | 25 266 (54.6) | ||

| African American | 17 333 (37.5) | 17 333 (37.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1856 (4.0) | 1856 (4.0) | ||

| Other | 1554 (3.3) | 1554 (3.3) | ||

| Asian | 87 (0.2) | 87 (0.2) | ||

| Native American or Alaskan | 104 (0.2) | 104 (0.2) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 26 (0.1) | 26 (0.1) | ||

| Multiracial | 32 (0.1) | 32 (0.1) | ||

| Age at first encounter, y, n, % | ||||

| <30 | 12 382 (26.8) | 12 382 (26.8) | ||

| ≥30 and <50 | 13 360 (28.9) | 13 360 (28.9) | ||

| ≥50 and <70 | 10 877 (23.5) | 10 877 (23.5) | ||

| ≥70 and <80 | 4874 (10.5) | 4874 (10.5) | ||

| ≥80 | 4763 (10.3) | 4763 (10.3) | ||

| Duration of the patient record in the database, mo, n, % | ||||

| <1 | 3446 (7.4) | 3450 (7.4) | ||

| ≥1 and <3 | 2155 (4.7) | 2152 (4.7) | ||

| ≥3 and <6 | 1098 (2.4) | 1099 (2.4) | ||

| ≥6 and <12 | 1385 (3.0) | 1385 (3.0) | ||

| ≥12 and <24 | 2547 (5.5) | 2545 (5.5) | ||

| ≥24 | 35 625 (77.0) | 35 625 (77.0) | ||

| Duration of encounter window, mo, n, % | ||||

| <1 | 13 620 (29.5) | 13 653 (29.5) | ||

| ≥1 and <3 | 2726 (5.9) | 2723 (5.9) | ||

| ≥3 and <6 | 1291 (2.8) | 1244 (2.8) | ||

| ≥6 and <12 | 2219 (4.8) | 2221 (4.8) | ||

| ≥12 and <24 | 3971 (8.6) | 3984 (8.6) | ||

| ≥24 | 22 429 (48.4) | 22 431 (48.4) | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.2 (8.7) | 28.0 (7.6) | 1.001 (0.995–1.008) | .14 |

| Imputed BMI, mean (SE)a | 27.9 (0.05) | 27.6 (0.04) | 1.006 (1.003–1.008) | <.0001 |

| Medication history, n, % | ||||

| Antipsychotic | 562 (1.2) | 298 (0.6) | 1.93 (1.67–2.22) | <.0001 |

| Estrogen | 355 (0.8) | 364 (0.8) | 0.97 (0.84–1.13) | .73 |

| Glucocorticoid | 1819 (3.9) | 1341 (2.9) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50) | <.0001 |

| NSAID | 2342 (5.1) | 1683 (3.6) | 1.45 (1.35–1.55) | <0.0001 |

| Opiate | 6453 (14.0) | 2748 (5.9) | 2.73 (2.60–2.87) | <.0001 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 3448 (7.5) | 2482 (5.4) | 1.46 (1.38–1.54) | <.0001 |

| Progesterone | 278 (0.6) | 205 (0.4) | 1.38 (1.15–1.66) | .001 |

| Antiepileptic | 144 (0.3) | 69 (0.1) | 2.09 (1.57–2.78) | <.0001 |

| SSRI | 1594 (3.4) | 1008 (2.2) | 1.63 (1.50–1.77) | <.0001 |

| Antidepressant | 310 (0.7) | 192 (0.4) | 1.62 (1.36–1.95) | <.0001 |

| Testosterone | 39 (0.08) | 43 (0.09) | 0.91 (0.59–1.40) | .66 |

| Thiazide | 1946 (4.2) | 1807 (3.9) | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | .02 |

| Loop diuretic | 1024 (2.2) | 815 (1.8) | 1.28 (1.16–1.40) | <.001 |

| Disease history, n, % | ||||

| Liver | 911 (2.0) | 800 (1.7) | 1.15 (1.04–1.26) | .006 |

| Heart failure | 1641 (3.5) | 1982 (4.3) | 0.81 (0.75–0.86) | <.0001 |

| Pulmonary | 7681 (16.6) | 7069 (15.3) | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | <.0001 |

| Central nervous system | 5253 (11.4) | 3776 (8.2) | 1.50 (1.43–1.57) | <.0001 |

| Malignancy | 475 (1.0) | 522 (1.1) | 0.91 (0.80–1.03) | .13 |

| Osteoporosis | 2094 (4.5) | 1199 (2.6) | 1.93 (1.79–2.09) | <.0001 |

| Hypotension | 1304 (2.8) | 753 (1.6) | 1.80 (1.64–1.97) | <.001 |

| Behavioral history, n, % | ||||

| Tobacco use | 9233 (20.0) | 6369 (13.8) | 1.67 (1.61–1.73) | <.0001 |

| Alcohol use | 1746 (3.8) | 1146 (2.5) | 1.58 (1.46–1.71) | <.0001 |

| Hyponatremia exposure, n, % | ||||

| Prior | 6429 (13.9) | 4482 (9.7) | 1.57 (1.50–1.64) | <.0001 |

| Chronic or recent hyponatremia exposure, n, % | ||||

| Not chronic or recentb | 41 269 (89.2) | 44 658 (96.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Only chronicb | 1597 (3.5) | 438 (0.9) | 4.14 (3.71–4.63) | <.0001 |

| Only recentb | 2571 (5.6) | 1078 (2.3) | 2.79 (2.58–3.01) | <.0001 |

| Chronic and recentb | 819 (1.8) | 82 (0.2) | 11.95 (9.44–15.13) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Missing BMI data for cases and controls were imputed from data of patients with BMI data available.

The ORs in these categories were generated from a single model. ORs need to be compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia.

An encounter window was defined for each osteoporosis and fracture case as the time between the date of the first encounter in the database and the date of the first osteoporosis diagnosis or first fragility fracture diagnosis, respectively. Encounter windows for controls were defined by the encounter window of the matched cases. A hypothetical time-to-event date for controls was calculated by adding the duration of the respective case's encounter window to the control's first encounter date. That is, the control encounter window was defined as the time between the date of the control's first encounter and a generated date representing the time to a hypothetical event (namely, an osteoporosis or fragility fracture diagnosis).

Case and control exposures to the clinical variables of interest were defined by the documentation of at least one disease diagnosis, drug prescription, or behavioral diagnostic code during the encounter window. Diagnostic codes for disease categories included in the analyses are provided in Supplemental Table 1. Of note, because of the hyperglycemia exclusion criterion, clinical variables including diabetes mellitus diagnosis and hypoglycemic agent use were not included. As explained in the discussion, use of antiresorptive agents was not considered independently. Case and control exposures for each of the hyponatremia variables were defined by serum Na+ laboratory measurements reported within the encounter windows. Exposure to prior hyponatremia was defined as having at least one serum Na+ measurement of less than 135 mmol/L within the encounter window. Exposure to chronic hyponatremia was defined as having at least two serum Na+ measurements of less than 135 mmol/L at least 1 year apart during the encounter window. Exposure to recent hyponatremia was defined as having at least one serum Na+ of less than 135 mmol/L within 30 days before the end of the encounter window. Exposure to only chronic hyponatremia was defined by meeting criteria for chronic hyponatremia but not recent hyponatremia. Patients categorized as having only recent hyponatremia had a hyponatremic value within 30 days before the close of the encounter window, may or may not have had a second Na+ value on record, and had no hyponatremic value at an interval one year or greater from the close of the encounter window. Exposure to recent and chronic hyponatremia was defined by meeting criteria for both recent and chronic hyponatremia. For the analysis of the association of the outcome measures with hyponatremia severity within the encounter window, the following categories were used: 1) no Na+ of less than 135 mmol/L; 2) median Na+ of 135 mmol/L or greater but one or more values of Na+ of less than135 mmol/L; 3) median Na+ of 134–130 mmol/L; and 4) median Na+ of less than 130 mmol/L.

The extent of missing body mass index (BMI) data for both osteoporosis and fragility fracture cases and controls necessitated imputation of BMI values for both osteoporosis and fragility fracture samples to run multivariate models adjusted for BMI on full data sets. Our methods for using multiple imputation methods for handling missing data are described elsewhere (19) and summarized in the Supplemental Materials.

Descriptive statistics such as means and SDs were used for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Conditional logistic regression for matched case-control design was used to estimate the change in the risk of osteoporosis and fractures in the form of the odds ratio (OR), which measures the change in the odds of experiencing the outcome (osteoporosis or fragility fracture), given the categories of an exposure variable. Statistical significance was determined with a value threshold of P= .05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and Stata version 11 (StataCorp).

Results

Final analyses of both the osteoporosis and fragility fracture cohorts with matched controls included 139 594 unique patient records. Records of 4313 patients that were used as a case or control in the osteoporosis or fracture analysis were used as a case or control in the other respective analysis.

A total number of 30 517 osteoporosis cases were matched to 30 517 controls without osteoporosis. Of the 57 028 potential osteoporosis cases, 12 045 (21.1%) were excluded because Na+ values were unavailable and 12 577 (22.1%) were excluded because of hyperglycemia. Of the remaining 32 406 osteoporosis cases, 1889 (5.8%) were excluded from the analysis because controls with matches on either the race, gender, age at first encounter, or duration of the patient record parameter were not obtained with the matching algorithm. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients with and without osteoporosis. Osteoporosis cases and controls were predominantly female (88.3%) and averaged 65.9 years of age (SD 14.7) at first encounter. Of the serum Na+ values for the osteoporosis cases and controls, 45.76% of the values were documented as acquired in the in-patient setting, 44.31% in the outpatient setting, 5.20% in the emergency department, and 4.73% unknown. Compared with patients without osteoporosis, patients with osteoporosis had a significantly lower BMI (27.0 vs 28.3 kg/m2). Unadjusted ORs indicate that being prescribed any of the pharmaceuticals listed, smoking, consuming alcohol, or having a history of any of the clinical variables listed except heart failure significantly increased the risk of osteoporosis.

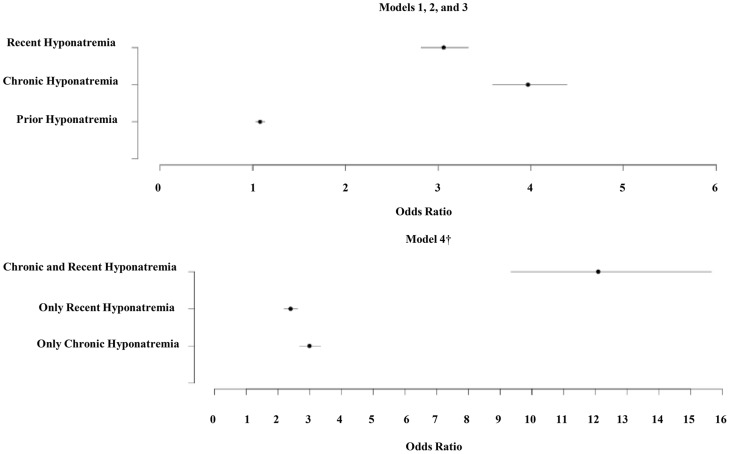

The results of the conditional multivariate logistic regression models for osteoporosis are presented in Table 3. All four models presented include the same list of covariates but differ in the type of hyponatremia variable: model 1 includes prior hyponatremia; model 2 includes chronic hyponatremia; model 3 includes recent hyponatremia; and model 4 includes an interaction of recent and chronic hyponatremia variables. Figure 1 summarizes the odds ratios of osteoporosis associated with the hyponatremia variables. Whereas the model with chronic hyponatremia has the largest OR [3.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.59–4.39, P < .001] among additive models 1–3, model 4 shows that the odds of osteoporosis for the patients identified as having both chronic and recent hyponatremia were higher by a factor of 12.09 (95% CI 9.34–15.66, P < .001) compared with those without either chronic or recent hyponatremia. This model also suggests that, compared with those without either chronic or recent hyponatremia, the odds of experiencing osteoporosis increased almost 2.4-fold if the patient had only recent hyponatremia and almost 3-fold if the patient had only chronic hyponatremia. Of the total 2788 patients classified as having only recent hyponatremia, there were only 454 patients (16.3%) with a Na+ value on record greater than 1 year from the end encounter window. Hence, some chronically hyponatremic patients may be represented in the recent-only hyponatremia cohort. ORs estimated for the osteoporosis dataset without adjustment for imputed BMI were similar to those in Table 3 to the second decimal point for most variables (results not shown).

Table 3.

Fully Adjusted Odds Ratios for Osteoporosis Study

| Model 1 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 2 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 3 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 4 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior hyponatremia | 1.078 (1.026–1.132)a | |||

| BMI (imputed) | 0.979 (0.974–0.984)b | 0.979 (0.975–0.984)b | 0.979 (0.975–0.984)b | 0.980 (0.975–0.984)b |

| Alcohol use | 1.166 (1.046–1.299)a | 1.139 (1.020–1.272)c | 1.166 (1.045–1.300a | 1.142 (1.022–1.275)c |

| Tobacco use | 1.322 (1.257–1.390)b | 1.295 (1.231–1.363)b | 1.314 (1.249–1.382)b | 1.291 (1.226–1.359)b |

| Antipsychotic | 1.383 (1.145–1.670)a | 1.394 (1.151–1.688)a | 1.377 (1.138–1.668)a | 1.380 (1.138–1.673)a |

| Estrogen | 1.297 (1.067–1.576)a | 1.319 (1.083–1.606)a | 1.334 (1.097–1.623)a | 1.346 (1.105–1.639)a |

| Glucocorticoid | 1.414 (1.299–1.539)b | 1.423 (1.306–1.551)b | 1.418 (1.302–1.545)b | 1.424 (1.306–1.553)b |

| NSAID | 1.080 (0.990–1.178) | 1.089 (0.997–1.188) | 1.089 (0.998–1.189) | 1.095 (1.003–1.196)c |

| Opiate | 1.450 (1.352–1.553)b | 1.432 (1.335–1.536)b | 1.424 (1.327–1.527)b | 1.407 (1.311–1.510)b |

| Thiazide | 1.182 (1.109–1.264)b | 1.159 (1.085–1.239)b | 1.180 (1.105–1.261)b | 1.159 (1.085–1.239)b |

| Loop diuretic | 1.023 (0.927–1.128) | 1.008 (0.912–1.114) | 1.004 (0.909–1.109) | 0.992 (0.897–1.098) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1.206 (1.129–1.289)b | 1.201 (1.123–1.284)b | 1.182 (1.106–1.264)b | 1.180 (1.103–1.262)b |

| Progesterone | 1.185 (0.921–1.525) | 1.181 (0.914–1.525) | 1.171 (0.907–1.512) | 1.165 (0.900–1.507) |

| Antiepileptic | 1.870 (1.259–2.778)a | 1.749 (1.169–2.616)a | 1.846 (1.236–2.756)a | 1.738 (1.156–2.613)a |

| SSRI | 1.097 (0.9996–1.203) | 1.088 (0.991–1.195) | 1.096 (0.998–1.203) | 1.090 (0.992–1.198) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 1.447 (1.181–1.773)b | 1.436 (1.169–1.763)a | 1.447 (1.179–1.776)b | 1.435 (1.167–1.764)a |

| Heart failure | 0.767 (0.715–0.822)b | 0.722 (0.672–0.775)b | 0.753 (0.702–0.808)b | 0.714 (0.664–0.767)b |

| Liver disease | 1.248 (1.119–1.392)b | 1.211 (1.083–1.354)b | 1.247 (1.117–1.393)b | 1.212 (1.084–1.356)a |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.181 (1.127–1.237)b | 1.156 (1.103–1.212)b | 1.163 (1.110–1.219)b | 1.142 (1.089–1.198)b |

| CNS disease | 1.202 (1.143–1.263)b | 1.177 (1.119–1.238)b | 1.204 (1.145–1.267)b | 1.180 (1.121–1.242)b |

| Malignancy | 0.995 (0.877–1.129) | 0.971 (1.119–1.238) | 0.997 (0.877–1.133) | 0.973 (0.855–1.108) |

| Chronic hyponatremia | 3.970 (3.590–4.390)b | |||

| Recent hyponatremia | 3.060 (2.814–3.326)b | |||

| No chronic or recent hyponatremiad | Reference group | |||

| Only chronicd | 2.991 (2.675–3.343)b | |||

| Only recentd | 2.394 (2.187–2.620)b | |||

| Chronic and recentd | 12.092 (9.339–15.655)b |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

P < .01.

P < .001.

P < .05.

The odds ratios in these categories were generated from a single model (model 4). ORs in model 4 need to be compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia.

Figure 1.

Fully adjusted ORs for hyponatremia variables in osteoporosis study. †, The odds ratios in these categories were generated from a single model (model 4). ORs in model 4 are compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia. Osteoporosis study ORs include the following: prior: 1.078 (1.026–1.132); chronic: 3.970 (3.590–4.390); recent: 3.060 (2.815–3.326); only chronic: 2.991 (2.675–3.343); only recent: 2.394 (2.187–2.620); chronic and recent: 12.092 (9.339–15.655).

A total number of 46 256 fragility fracture cases were matched to 46 256 controls without fragility fracture. Of the 116 153 potential fragility fracture cases, 50 756 (43.7%) were excluded because Na+ values were unavailable and 16 863 (14.5%) were excluded because of hyperglycemia. Of the remaining 48 534 fragility fracture cases, 2278 (4.7%) were excluded from the analysis because controls were not obtained with the matching algorithm. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the patients with and without fragility fracture. Fragility cases and controls were mostly female (55.4%) and averaged 47.4 years (SD 22.8) at first encounter. Of the serum Na+ values for fragility fracture cases and controls, 49.48% were documented as acquired in the in-patient setting, 34.84% in the outpatient setting, 10.90% in the emergency department, and 4.78% unknown. Compared with patients without fragility fracture, patients with fragility fracture had a higher mean BMI (28.2 vs 28.0 kg/m2). Unadjusted ORs indicate that being prescribed any of the pharmaceuticals listed except estrogen and T, smoking, consuming alcohol, or having a history of the any of the diseases listed except heart failure or malignancy significantly increased the risk of fragility fracture.

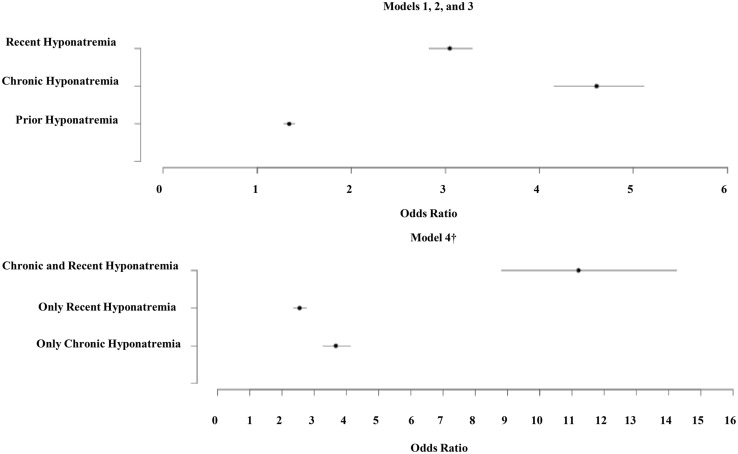

The results of the conditional multivariate logistic regression models for fragility fracture are presented in Table 4. Similar to the analyses performed for the osteoporosis data set, all four models presented include the same list of covariates but differ in the type of hyponatremia variable: model 1 includes prior hyponatremia; model 2 includes chronic hyponatremia; model 3 includes recent hyponatremia; and model 4 includes an interaction of recent and chronic hyponatremia variables. Figure 2 summarizes the ORs of fragility fracture associated with the hyponatremia variables. Whereas the model with chronic hyponatremia has the largest OR (4.61, 95% CI 4.15–5.11, P < .001) among additive models 1–3, model 4 shows that the odds of fragility fracture for the patients identified as having both chronic and recent hyponatremia were higher by a factor of 11.21 (95% CI 8.81–14.26, P < .001) compared with those without either chronic or recent hyponatremia. This model also suggests that, compared with those without either chronic or recent hyponatremia, the odds of experiencing fragility fracture increased almost 2.6-fold if the patient had only recent hyponatremia and almost 3.7-fold if the patient had only chronic hyponatremia. Of the total 3649 patients classified as having only recent hyponatremia, there were only 537 patients (14.7%) on record with a Na+ value greater than 1 year from the end of the encounter window. Hence, some chronically hyponatremic patients may be represented in the recent-only hyponatremia cohort. ORs estimated for the fragility fracture data set without adjustment for imputed BMI were similar to those in Table 4 to the second decimal point for most of variables (results not shown). Summary of analyses from both Tables 3 and 4 are presented in Supplemental Table 2 and demonstrates a markedly increased risk of osteoporosis and fragility fracture with both recent and sustained hyponatremia.

Table 4.

Fully Adjusted ORs for Fragility Fracture Study

| Model 1 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 2 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 3 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Model 4 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior osteoporosis | 1.821 (1.679–1.976)a | 1.784 (1.641–1.940)a | 1.854 (1.707–2.013)a | 1.795 (1.649–1.953)a |

| Prior hyponatremia | 1.339 (1.279–1.402)a | |||

| BMI (imputed) | 1.008 (1.006–1.010)a | 1.008 (1.006–1.010)a | 1.008 (1.006–1.010)a | 1.008 (1.006–1.010)a |

| Alcohol use | 1.324 (1.218–1.440)a | 1.275 (1.171–1.388)a | 1.318 (1.212–1.434)a | 1.268 (1.164–1.381)a |

| Tobacco use | 1.544 (1.483–1.608)a | 1.536 (1.475–1.600)a | 1.558 (1.495–1.622)a | 1.536 (1.474–1.600)a |

| Antipsychotic | 1.014 (0.868–1.185) | 1.016 (0.868–1.189) | 1.020 (0.871–1.195) | 1.018 (0.868–1.193) |

| Estrogen | 0.932 (0.795–1.092) | 0.942 (0.803–1.105) | 0.953 (0.813–1.116) | 0.961 (0.819–1.127) |

| Glucocorticoid | 0.996 (0.918–1.081) | 0.997 (0.917–1.083) | 0.996 (0.917–1.082) | 0.996 (0.917–1.083) |

| NSAID | 0.991 (0.920–1.067) | 0.995 (0.923–1.072) | 1.000 (0.928–1.078) | 1.004 (0.932–1.083) |

| Opiate | 2.662 (2.518–2.814)a | 2.711 (2.563–2.867)a | 2.620 (2.477–2.770)a | 2.618 (2.475–2.770)a |

| Thiazide | 0.862 (0.799–0.930)a | 0.851 (0.788–0.920)a | 0.872 (0.808–0.941)b | 0.860 (0.795–0.929)a |

| Loop diuretic | 0.965 (0.902–1.033) | 0.931 (0.869–0.997)c | 0.977 (0.913–1.046) | 0.945 (0.882–1.014) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 0.865 (0.810–0.924)a | 0.871 (0.815–0.931)a | 0.855 (0.800–0.914)a | 0.845 (0.790–0.903)a |

| Progesterone | 0.990 (0.810–1.210) | 0.981 (0.801–1.201) | 0.966 (0.789–1.183) | 0.955 (0.779–1.170) |

| Antiepileptic | 1.381 (1.016–1.877)c | 1.361 (0.996–1.861) | 1.427 (1.047–1.944)c | 1.378 (1.006–1.887)c |

| SSRI | 1.236 (1.130–1.352)a | 1.220 (1.113–1.336)a | 1.244 (1.137–1.362)a | 1.235 (1.127–1.353)a |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 1.063 (0.873–1.295) | 1.058 (0.866–1.294) | 1.063 (0.872–1.296) | 1.051 (0.860–1.286) |

| Heart failure | 0.615 (0.569–0.665)a | 0.587 (0.542–0.636)a | 0.625 (0.578–0.677)a | 0.582 (0.537–0.632)a |

| Liver disease | 0.865 (0.779–0.961)b | 0.838 (0.753–0.933)b | 0.873 (0.786–0.970)c | 0.835 (0.749–0.930)b |

| Pulmonary disease | 0.963 (0.925–1.003) | 0.957 (0.918–0.997)c | 0.968 (0.930–1.008) | 0.953 (0.915–0.993)c |

| CNS disease | 1.356 (1.291–1.426)a | 1.358 (1.292–1.429)a | 1.381 (1.313–1.452)a | 1.367 (1.299–1.438)a |

| Malignancy | 0.719 (0.627–0.823)a | 0.701 (0.611–0.805)a | 0.697 (0.608–0.800)a | 0.675 (0.587–0.777)a |

| Hypotension | 1.337 (1.265–1.414)a | 1.258 (1.189–1.332)a | 1.305 (1.234–1.381)a | 1.215 (1.146–1.287)a |

| Chronic hyponatremia | 4.608 (4.153–5.114)a | |||

| Recent hyponatremia | 3.047 (2.826–3.286)a | |||

| No chronic or recent hyponatremiad | Reference group | |||

| Only chronicd | 3.670 (3.269–4.121)a | |||

| Only recentd | 2.545 (2.349–2.757)a | |||

| Chronic and recentd | 11.211 (8.812–14.263)a |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

P < .001.

P < .01.

P < .05.

The ORs in these categories were generated from a single model (model 4). ORs in model 4 need to be compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia.

Figure 2.

Fully adjusted ORs for hyponatremia variables in fragility fracture study. †, The ORs in these categories were generated from a single model (model 4). ORs in model 4 are compared with the reference category of no recent and no chronic hyponatremia. Fragility fracture study ORs include the following: prior: 1.339 (1.297–1.402); chronic: 4.608 (4.153–5.114); recent: 3.047 (2.826–3.286); only chronic: 3.670 (3.269–4.121); only recent: 2.545 (2.349–2.757); chronic and recent: 11.211 (8.812–14.263).

Multiple logistic regression analysis with no Na+ value of less than 135 mmol/L as the reference variable and inclusion of all previous covariates except BMI demonstrated that incremental decreases in median Na+ were correlated with increasing OR of osteoporosis or fragility fracture: median Na+ of 135 mmol/L or greater but one or more Na+ values of less than 135 mmol/L (osteoporosis: OR 3.55, 95% CI 3.12–4.05; fragility fracture: OR 4.45, 95% CI 3.88–5.11); median Na+ of 134–130 mmol/L (osteoporosis: OR 4.42, 95% CI 3.79–5.15; fragility fracture: OR 4.54, 95% CI 3.88–5.31); and median Na+ of less than130 mmol/L (osteoporosis: OR 6.64, 95% CI 3.85–11.48; fragility fracture: OR 7.02, 95% CI 3.94–12.51).

Discussion

In the largest published prospective study of risk of osteoporosis and fragility fracture associated with hyponatremia (the Rotterdam study), bone mineral density (BMD) was not associated with low serum Na+ (13). The findings of the present study potentially clarify and expand the findings of the Rotterdam study. Consistent with the Rotterdam study, we report that prior hyponatremia alone increases the odds of osteoporosis to a small extent. However, when the analysis is expanded beyond the analysis of a single serum Na+ value (as is done in the Rotterdam study) to include the variable of chronic hyponatremia over at least 1 year, osteoporosis odds increase to almost 4-fold. That chronic hyponatremia is strongly associated with increased odds of osteoporosis whereas prior hyponatremia is associated with an increased odds of osteoporosis to a lesser extent is consistent with the proposed pathogenesis of hyponatremia-induced osteoporosis in animal studies and recent case reports (8, 14). A study of single serum Na+ values 14 days before or after imaging suggested a modest dose-response between increasing serum Na+ and increasing total hip bone mineral content, BMD, and T-score (20). A recent study of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry data from patients who had at least one hyponatremic interval in the 2 years prior to densitometry suggested that more severe and longer duration hyponatremia was associated with highest risk of osteoporosis in younger patients (21). The present study provides further evidence that the association between hyponatremia and osteoporosis is dose dependent (more severe hyponatremia results in higher elevated risk) and time dependent (chronic hyponatremia results carries higher risk than prior hyponatremia alone). Furthermore, the present finding that recent hyponatremia carries a higher odds of osteoporosis than prior hyponatremia supports the hypothesis that hyponatremia-induced bone loss is reversible. That is, although we cannot exclude the possibility that chronically hyponatremic patients are represented in both the prior and recent hyponatremia groups (because of missing Na+ measurements), the lower risk of osteoporosis with prior hyponatremia than with recent hyponatremia suggests that patients may recover bone mass if hyponatremia is reversed.

In the Rotterdam study, hyponatremia at study entry was associated with a 1.4-fold increase in nonvertebral fractures over 7.4 years of follow-up and a 1.8-fold increase of prevalent but not incident vertebral or hip fractures. Similar but more robust findings were reported in an analysis of data from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men study (12). In a case-control study of 513 cases of bone fractures after incidental falls in ambulatory patients aged 65 years or older, Gankam et al (10) report that hyponatremia (mean serum Na+ 131 mEq/L) was associated with bone fracture with an adjusted odds ratio of 4.16 (95% CI 2.24–7.71). Our study finds that recent hyponatremia, which was defined as serum Na+ of less than 135 mmol/L within 30 days of the outcome measure, was associated with fragility fracture with an OR of 3.047. Distinguishing between prior, recent, and chronic hyponatremia potentially clarifies the apparent discrepancy between the more modest fracture odds ratios observed in the Rotterdam study, which used a single serum Na+ value at study entry over 7.4 years of follow-up to evaluate the hyponatremia parameter, and the larger OR observed in the study by Gankam et al, which evaluated pretreatment serum Na+ on the day of the fall. That is, the Rotterdam study evaluated a prior hyponatremia parameter, which is associated with only a modest increased fracture risk, whereas Gankam et al measured a recent hyponatremia parameter, which carries a higher risk.

Consistent with Kinsella et al (22) suggesting that hyponatremia is associated with fracture independent of osteoporosis, a study showing gait instability with hyponatremia (15), and recent studies showing hyponatremia as an independent predictor of falls in a geriatric population (16) and in hospitalized patients (17), our findings demonstrate that recent hyponatremia is an even greater risk factor for fragility fracture than prior hyponatremia alone. Thus, the association between hyponatremia and fragility fracture may not be merely related to chronic bone loss but also due to a more acute process, such as hyponatremia-induced gait instability leading to increased falls. When patients have both chronic and recent hyponatremia, the risk of fragility fracture is greater than the risk of fracture with recent hyponatremia or chronic hyponatremia alone, further suggestive that two distinct mechanisms underlie the association between hyponatremia and fragility fracture. Our study suggests that, because different types of hyponatremia are associated with different levels of risk, it is important clinically to distinguish among a short and proximate hyponatremic event, a chronic hyponatremia pattern, and a brief hyponatremic episode in the distant past.

Some of the findings reported here remain unexplained. For example, inconsistent with recent literature (23, 24), our models suggest that heart failure is modestly associated with a decreased odds of osteoporosis and fragility fracture. Inconsistent with other literature, odds ratios for osteoporosis associated with use of estrogens and Ts are greater than 1 in the present study. Nevertheless, there is literature negating a protective effect of estrogens on bone among adolescents and young women (25) who, although not the predominant subgroup, were represented in the present study. Finally, literature paradoxically suggests that thiazides may be protective against osteoporosis and/or fragility fracture (26, 27) and that thiazide-induced hyponatremia may increase risk of osteoporosis and/or fragility fractures (28, 29). The ORs for the association between thiazide use and osteoporosis are increased in the present study, and we posit that the associations among thiazide use, hyponatremia, and osteoporosis warrant further study. Because this study matches cases and controls on length of the patient record and creates a window within the available patient record, emigration or death of cases or controls does not explain the present findings.

Our study has several limitations. First, because we exclude patients with hyperglycemia, it is difficult to generalize our results to uncontrolled persons with diabetes. We chose to exclude hyperglycemic patients with the most conservative measure (single glucose values > 200 mg/dL) because it is important clinically to distinguish hypotonic hyponatremia (the entity of interest in this study) from isotonic and hypertonic hyponatremia, which is usually due to diabetic hyperglycemia and is associated with artifactual decreases in serum sodium concentration (30). Second, we did not include the potential confounder of use of antiresorptives in our analyses because these agents were found to be strongly positively associated with osteoporosis. This analytical paradox is easily explained clinically: antiresorptives are most frequently prescribed to patients with or vulnerable to disease that impacts bone quality. Third, our use of diagnostic codes and serum Na+ status limited our analysis: BMD data were not available to evaluate osteoporosis severity or anatomical site, criterion for determining osteoporosis or fracture diagnosis (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scan diagnosed osteoporosis vs low energy fracture osteoporosis) was unobtainable, and the individual etiology of patient hyponatremia could not be assessed. Fourth, limited BMI data made imputation necessary. Fifth, use of a clinical database made it impossible to address the mechanistic controversy that surrounds this area of research (31, 32). Specifically, we did not have arginine vasopressin levels.

This investigation adds to the accumulating evidence that even mild hyponatremia may have clinical implications for patient risk of osteoporosis and fragility fracture. We differentiate odds of osteoporosis and fragility fracture associated with different clinical patterns and degrees of severity of hyponatremia. Importantly, a recent case report showed that reversal of chronic hyponatremia could result in the spontaneous partial reversal of osteoporosis. Therefore, not only are the associations between hyponatremia, osteoporosis, and fragility fracture strong and variable dependent on the clinical picture but also potentially reversible. More studies, such as prospective trials of reversal of hyponatremia with monitoring of bone quality, falls, and fractures, are warranted to evaluate whether treatment of a highly prevalent electrolyte disorder could result in improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Rachel L. (Sr.Grace Miriam) Usala, R.S.M., completed this project as her practicum for a Master of Science degree in the Systems Medicine MD/MS Program of Georgetown University under the directorship of Dr Sona Vasudevan.

This work was supported in whole or in part by Grant UL1TR000101 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program, a trademark of the Department of Health and Human Services, a part of the Roadmap Initiative, “Re-Engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise.”

Disclosure Summary: J.G.V. has received grant support from Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc as well as noncontinuing medical education-related fees from Cardiokine, Cornerstone Therapeutics, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- BMI

- body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- OR

- odds ratio.

References

- 1. Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2006;119(7 suppl 1):S30–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wald R, Jaber BL, Price LL, Upadhyay A, Madias NE. Impact of hospital-associated hyponatremia on selected outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(3):294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corona G, Giuliani C, Parenti G, et al. Moderate hyponatremia is associated with increased risk of mortality: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1018–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klein L, O'Connor CM, Leimberger JD, et al. Lower serum sodium is associated with increased short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with worsening heart failure: results from the Outcomes of a Prospective Trial of Intravenous Milrinone for Exacerbations of Chronic Heart Failure (OPTIME-CHF) study. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2454–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, et al. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2099–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harrison HE. The sodium content of bone and other calcified material. J Biol Chem. 1937;120:457–462. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verbalis JG, Barsony J, Sugimura Y, et al. Hyponatremia-induced osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(3):554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barsony J, Manigrasso MB, Xu Q, Tam H, Verbalis JG. Chronic hyponatremia exacerbates multiple manifestations of senescence in male rats. Age (Dordr). 2013;35(2):271–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gankam KF, Andres C, Sattar L, Melot C, Decaux G. Mild hyponatremia and risk of fracture in the ambulatory elderly. QJM. 2008;101(7):583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sandhu HS, Gilles E, DeVita MV, Panagopoulos G, Michelis MF. Hyponatremia associated with large-bone fracture in elderly patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41(3):733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jamal SA, Arampatzis S, Harrison SL, et al. Hyponatremia and Fractures: findings from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(6):970–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoorn EJ, Rivadeneira F, van Meurs JB, et al. Mild hyponatremia as a risk factor for fractures: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(8):1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sejling AS, Thorsteinsson AL, Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Eiken P. Recovery from SIADH-associated osteoporosis: a case report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3527–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X, Manto MU, Decaux G. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rittenhouse KJ, To T, Rogers A, et al. Hyponatremia as a fall predictor in a geriatric trauma population. Injury. 2015;46(1):119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tachi T, Yokoi T, Goto C, et al. Hyponatremia and hypokalemia as risk factors for falls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(2):205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaelber DC, Foster W, Gilder J, Love TE, Jain AK. Patient characteristics associated with venous thromboembolic events: a cohort study using pooled electronic health record data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(6):965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stata Corp. Stata Muliple Imputation Reference Manual. College Station, TX: Stata Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kruse C, Eiken P, Vestergaard P. Hyponatremia and osteoporosis: insights from the Danish National Patient Registry. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(3):1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Afshinnia F, Sundaram B, Ackermann RJ, Wong KK. Hyponatremia and osteoporosis: reappraisal of a novel association [published online March 26, 2015]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kinsella S, Moran S, Sullivan MO, Molloy MG, Eustace JA. Hyponatremia independent of osteoporosis is associated with fracture occurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aluoch AO, Jessee R, Habal H, et al. Heart failure as a risk factor for osteoporosis and fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012;10(4):258–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfister R, Michels G, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Low bone mineral density predicts incident heart failure in men and women: the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition)-Norfolk prospective study. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(4):380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scholes D, Hubbard RA, Ichikawa LE, et al. Oral contraceptive use and bone density change in adolescent and young adult women: a prospective study of age, hormone dose, and discontinuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):E1380–E1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolland MJ, Ames RW, Horne AM, Orr-Walker BJ, Gamble GD, Reid IR. The effect of treatment with a thiazide diuretic for 4 years on bone density in normal postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(4):479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aung K, Htay T. Thiazide diuretics and the risk of hip fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD005185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arampatzis S, Gaetcke LM, Funk GC, et al. Diuretic-induced hyponatremia and osteoporotic fractures in patients admitted to the emergency department. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Kwan BC, Ma TK, Leung CB, Li PK. Fracture risk after thiazide-associated hyponatraemia. Intern Med J. 2012;42(7):760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013;126(10 suppl 1):S1–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tamma R, Sun L, Cuscito C, et al. Regulation of bone remodeling by vasopressin explains the bone loss in hyponatremia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(46):18644–18649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hannon MJ, Verbalis JG. Sodium homeostasis and bone. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(4):370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]