Abstract

Context:

GH and IGF-I have important roles in the maintenance of substrate metabolism and body composition. However, when in excess in acromegaly, the lipolytic and insulin antagonistic effects of GH may alter adipose tissue (AT) deposition.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of surgery for acromegaly on AT distribution and ectopic lipid deposition in liver and muscle.

Design:

This was a prospective study before and up to 2 years after pituitary surgery.

Setting:

The setting was an academic pituitary center.

Patients:

Participants were 23 patients with newly diagnosed, untreated acromegaly.

Main Outcome Measures:

We determined visceral (VAT), subcutaneous (SAT), and intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), and skeletal muscle compartments by total-body magnetic resonance imaging, intrahepatic and intramyocellular lipid by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and serum endocrine, metabolic, and cardiovascular risk markers.

Results:

VAT and SAT masses were lower than predicted in active acromegaly, but increased after surgery in male and female subjects along with lowering of GH, IGF-I, and insulin resistance. VAT and SAT increased to a greater extent in men than in women. Skeletal muscle mass decreased in men. IMAT was higher in active acromegaly and decreased in women after surgery. Intrahepatic lipid increased, but intramyocellular lipid did not change after surgery.

Conclusions:

Acromegaly may present a unique type of lipodystrophy characterized by reduced storage of AT in central depots and a shift of excess lipid to IMAT. After surgery, this pattern partially reverses, but differentially in men and women. These findings have implications for understanding the role of GH in body composition and metabolic risk in acromegaly and other clinical settings of GH use.

GH and IGF-I are key regulators of fat and carbohydrate metabolism and body composition. GH is insulin antagonistic, anabolic, and lipolytic (1). In acromegaly, characterized by excess circulating levels of GH and IGF-I, the GH effects predominate to produce a clinical phenotype that includes insulin resistance and a reduced fat mass as detected by traditional methods such as the 4-compartment model, bioimpedance, or dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (2–4). Utilizing total-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a state-of-the-art technique for measuring adipose tissue (AT) distribution, we found in our prior cross-sectional study that patients with active acromegaly and insulin resistance had lower than predicted visceral adipose tissue (VAT) mass yet higher than predicted intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), an AT depot also associated with insulin resistance (5). These data suggest that acromegaly, despite its associated increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, presents an atypical pattern with regard to VAT and insulin resistance because in other populations, lower central adiposity is generally associated with less insulin resistance and CV risk (6). Whether or not these patterns of VAT and IMAT deposition reverse with successful surgical therapy of acromegaly is unknown. Only 1 prior study in 15 patients measured VAT volume prospectively, before and after surgical therapy (7). It is also unknown whether this altered body composition, because of its underlying accelerated lipolysis and free-fatty acid flux, could be associated with ectopic deposition of lipid in liver or muscle. The latter could contribute to the metabolic abnormalities and CV risk of acromegaly, consistent with that seen in other populations (8).

Therefore, we sought to investigate, for the first time, the effect of surgical treatment of acromegaly on adipose tissue distribution in a combined assessment of total body AT and skeletal muscle (SM) mass by MRI and ectopic lipid deposition in liver and muscle by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). A secondary aim was to investigate how sex and changes in insulin resistance and GH and IGF-I levels relate to changes in body composition from before and up to 2 years after pituitary surgery.

Materials and Methods

Subjects with acromegaly

We prospectively studied 23 subjects (10 men and 13 women) (17 Caucasian and 6 Hispanic) with untreated acromegaly that was newly diagnosed by an elevated IGF-I level, a nadir GH level after oral glucose of >1 μg/L (0.75 μg/L in 1 subject), and characteristic clinical features. The preoperative characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Prolactin levels preoperatively were normal (<19 ng/mL) in all but 4 women with macroadenomas (range, 24–39 ng/mL). Preoperatively, 3 men had secondary hypogonadism (testosterone levels of 170, 230, and 250 ng/mL [normal, 270–1070 ng/mL]) that resolved postoperatively, spontaneously in 2 and 1 with testosterone replacement. One women had secondary amenorrhea preoperatively and regular menses postoperatively and 1 woman became postmenopausal postoperatively. Two men received thyroid and adrenal replacement preoperatively and postoperatively one stopped therapy. After baseline testing, all underwent transsphenoidal surgical resection with pathological confirmation of a GH-secreting pituitary tumor. Subsequently, none received medical therapy for acromegaly, radiotherapy, or additional surgery during their observation period in this study. Preoperative and postoperative endocrine data were reported in 15 subjects (7 women and 8 men) (9). Baseline body composition testing was reported in 4 subjects (2 women and 2 men) (10). All subjects were ambulatory with normal renal and liver function. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University Medical Center. All subjects gave written informed consent before participation.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics, and Endocrine, Metabolic, and Anthropometric Parameters in Male and Female Patients With Acromegaly Preoperatively and 1 Year Postoperatively

| Male Patients (n = 10) |

Preoperative vs Postoperative P Value | Female Patients (n = 13) |

Preoperative vs Postoperative P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperativea | Preoperative | Postoperativea | |||

| Age, y | 39 ± 13 (18–54) | 48 ± 12 (23–69) | ||||

| Weight, kg | 100.5 ± 11.6 | 101.4 ± 13.8 | .37 | 76.8 ± 15 | 77 ± 15 | .67 |

| Height, cm | 184.2 ± 7.4 | 183.8 ± 7.4 | .38 | 166.2 ± 7.2 | 166.3 ± 6.9 | .76 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 4 | 30.5 ± 3.6 | .32 | 27.4 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | .46 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.8 ± 13.8 | 100.2 ± 9.7 | .6 | 83.4 ± 11.5 | 82 ± 11.5 | .67 |

| Symptom duration before diagnosis, y | 3.8 ± 2.7 | 5.4 ± 7.1 | ||||

| Pituitary tumor size (micro/macro) | 3/7 | 3/10 | ||||

| Hormone replacement | GC (2), T4 (2) | GC (1), T4 (1), T (1) | ||||

| Gonadal function | H (3), Eu (7) | Eu (10) | PM (4), H (1), Eu (8) | PM (5), Eu (8) | ||

| Hypertension | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | |||||

| Sleep apnea | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Lipid lowering drugs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| IGF-I, ng/mLb | 719 ± 171 | 266 ± 146 | .002 | 707 ± 189 | 234 ± 56 | .01 |

| IGF-I, % ULN | 238 ± 52 | −18 ± 43 | <.0001 | 270 ± 70 | −17 ± 26 | <.0001 |

| GH fasting, μg/L | 23 ± 32 | 2 ± 0.54 | .002 | 32 ± 64 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | .01 |

| GH nadir OGTT, μg/L | 19 ± 23 | 0.85 ± 2 | .002 | 23 ± 43 | 0.58 ± 0.38 | .01 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 92 ± 8.9 | 82 ± 8.9 | .04 | 91 ± 11.5 | 84 ± 10 | .04 |

| HOMA-IR scorec | 4.2 ± 2.6 | 1.75 ± 1.4 | .004 | 3.03 ± 2.6 | 0.72 ± 0.41 | .01 |

| Comp ISId | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 9.2 ± 7 | .01 | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 11.4 ± 6.4 | .002 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 2.1 | .023 | 0.71 ± 0.95 | 0.53 ± 0.42 | .21 |

| HCY, μmol/L | 7.8 ± 1.9 | 10.5 ± 2.7 | .07 | 9.8 ± 8.7 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | .09 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 5.7 ± 4.0 | 8.3 ± 5.4 | .19 | 21 ± 23 | 32 ± 24 | .03 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; Comp ISI, composite insulin sensitivity index; Eu, eugonadal; GC, oral glucocorticoid replacement therapy; H, hypogonadal with no replacement therapy; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; PM, postmenopausal, no hormone replacement therapy; T, testosterone replacement therapy; T4, thyroxine replacement therapy; ULN upper limit of normal. Data are means ± SD (range) or number of subjects.

Postoperative data are only from 1 year postoperatively to simplify data presentation and in general did not differ from those at 6 months and 2 years.

Normal IGF-I ranges: age 19, 141–483 ng/mL; age 20, 127–424 ng/mL; ages 21–25 116–358 ng/mL; ages 26–30, 117–329 ng/mL; ages 31–35, 115–307 ng/mL; ages 36–40, 109–284 ng/mL; ages 41–45, 101–267 ng/mL; ages 46–50, 94–252 ng/mL; ages 51–55, 87–238 ng/mL; ages 56–60, 81–225 ng/mL; ages 61–65, 75–212 ng/mL; and ages 66–70, 69–200 ng/mL.

HOMA-IR scores = [fasting serum insulin (microunits per milliliter) × fasting plasma glucose (millimoles per liter)/22.5).

Comp ISI = [10 000/square root of (fasting glucose in milligrams per deciliter × fasting insulin in microunits per milliliter) × (mean glucose × mean insulin OGTT)].

Study design

Subjects were studied before and 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively with blood sampling, after an overnight fast, for IGF-I, GH, insulin, glucose, leptin, C-reactive protein (CRP) and homocysteine and for GH, glucose, and insulin at 60, 90, and 120 minutes after 100 g of oral glucose (oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]; Trutol 100). Physical examination including anthropometrics, body weight by digital scale (nearest 0.01 kg), height by stadiometer (nearest 0.5 cm), waist circumference, and a detailed history were obtained. On a separate day, after an overnight fast, subjects underwent total-body MRI body composition testing before surgery and at 1 or more follow-up visits; 17 subjects were tested at 6 months (7 men and 10 women), 17 at 1 year (9 men and 8 women) and 12 at 2 years (6 men and 6 women) after surgery. Total and regional body AT volumes were measured by total-body multislice MRI on a 1.5-T magnetic resonance scanner (Achieva; Philips Healthcare) as described previously (10, 11). Trunk AT was defined as all AT in the body from the shoulders (upper limit as separation between arms and neck) to the pelvis (lower limit as level of separation of legs). Limb AT was defined as the sum of SAT and IMAT of arms and legs. The IMAT, defined as AT located between muscle groups and beneath the muscle fascia (12), does not include intramyocellular lipid (IMCL), ie, lipid within muscle cells. Images were analyzed with SliceOmatic image analysis software (TomoVision) in the New York Obesity Research Center Image Analysis Laboratory. MRI volume estimates were converted to mass using the assumed density of 0.92 kg/L for AT and 1.04 kg/L for SM. The coefficients of variation for repeated same scan, same observer measurements of MRI-derived AT volumes are 1.7% for SAT, 2.3% for VAT, and 5.9% for IMAT (10–12).

Concurrently, in a subgroup, we acquired water-suppressed and non–water-suppressed single-voxel 1H MRS (by applying the point-resolved spectroscopy technique) of the liver for measurement of intrahepatic lipid (IHL) (n = 12; 7 men and 5 women) and tibialis anterior muscle for measurement of IMCL (n = 14; 9 men and 5 women). Muscle MRS was acquired using the knee-foot coil supplied by the vendor with the parameters: voxel size = 15 × 15 × 45 mm3, repetition time/echo time = 2000/40 msec, spectral bandwidth = 1000 Hz, samples = 512, averages = 40, water suppression = excitation (window = 80 Hz, second pulse angle = 300), and duration = 1:24 minutes. The methyl (–CH3) and methylene (–CH2) groups of lipids were quantified in the non–water-suppressed spectrum. Liver MRS was acquired using a multielement SENSE-cardiac coil also supplied by the vendor with similar parameters except voxel = 30 × 30 × 30 mm3 and water suppression = excitation (window = 100 Hz, second pulse angle = 300). Balanced gradient echo anatomical images were captured in 3 planes for localization and planning of the point-resolved spectroscopy box. The non–water-suppressed spectrum was phased and frequency shifted, and the water peak at 4.67 ppm was fitted with a Gaussian peak (3 baseline terms and 90% characteristics) using Philips advance spectroscopy analysis software. The methyl (–CH3) and methylene (–CH2) groups of lipids were quantified in the water-suppressed spectrum and normalized to water.

Hormone assays

GH, IGF-I, insulin, and CRP were measured by chemiluminescent immunometric assays and homocysteine by a competitive immunoassay from IMMULITE (Siemens). The functional sensitivities for GH, CRP, and homocysteine were 0.05 μg/L, 0.3 mg/L, and 0.5 μmol/L, respectively. The IGF-I levels were compared with their age-appropriate normal ranges (Table 1). Glucose was measured by the hexokinase method and leptin by a human RIA kit (Millipore Research).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated: frequencies for categorical data and means ± SD for continuous data. Predicted values for masses of total adipose tissue (TAT), VAT, and SAT compartments were calculated based on previously derived prediction equations developed using generalized linear models accounting for sex, age, height, weight, and race (10, 11) and for IMAT (12) (Supplemental Table 1). IMAT in Hispanics was not compared with predicted values because this model was unavailable. The observed acromegaly values were compared with the predicted values. Comparisons were performed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables. The χ2 test for trend was used to compare the proportion of subjects with values above or below the predicted values over time. Spearman rank correlation tests were used to assess the relationship between preoperative and postoperative changes in the levels of IGF-I, GH, leptin, or homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) score and those of the AT compartment. Descriptions of AT data refer to mass of that compartment. Analyses were performed with Prism 6.0 for MAC. P values of <.05 were considered significant.

Results

Anthropometrics

BMI, body weight, height, and waist circumference did not change after surgery (Table 1).

Body composition (summarized in Supplemental Table 2)

VAT

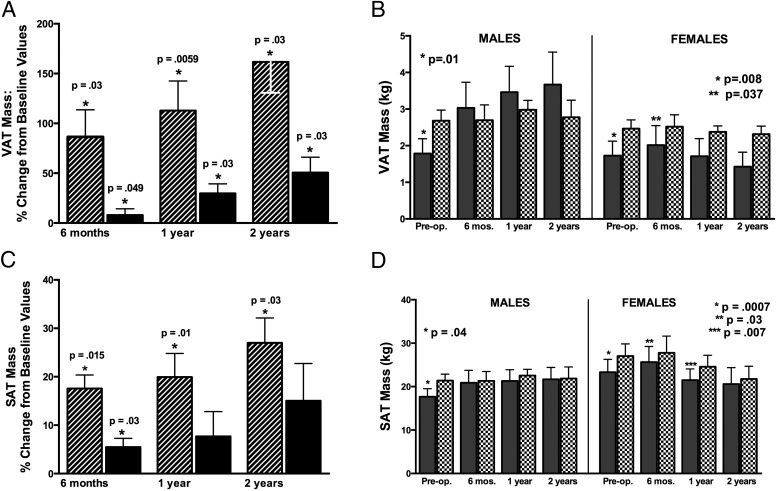

VAT increased after surgery in both men and women (Figure 1A). The percent rise in VAT from preoperatively to postoperatively was greater in men than in women at 6 months (P = .0047), 1 year (P = .04), and 2 years (P = .03) (Figure 1A). Preoperatively, VAT was below predicted values in both men and women (Figure 1B), and the VAT/VAT predicted ratio did not differ in men and women (P = .63). The proportion of subjects with VAT below vs above predicted values fell in men from 90% preoperatively to 33% at 2 years (P = .02), but did not change in women (92% to 80%) (P = .51).

Figure 1.

A, Mean percent change in VAT mass from preoperative VAT mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (black bars). The preoperative to postoperative percent change represents that for subjects tested only at the respective postoperative time point, and the P value represents significance of this change: change at 6 months is that for the 17 subjects tested at 6 months, change at 1 year is the that for the 17 tested at 1 year, and change at 2 years is that for the 12 tested at 2 years. B, Mean VAT mass in male (left) and female (right) subjects with acromegaly (shaded bars) compared with predicted values (patterned bars) preoperatively and at follow-up after surgery. P values compare acromegaly with predicted values for subjects with acromegaly tested at that time point. C, Mean percent change in SAT mass from preoperative SAT mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (black bars). P values represent significance of change from preoperative to postoperative follow-up. D, Mean SAT mass in male (left) and female (right) subjects with acromegaly (shaded bars) compared with predicted values (patterned bars) preoperatively and at follow-up after surgery. P values compare acromegaly with predicted values.

SAT

SAT increased after surgery in men and women (Figure 1C). The percent increase in SAT was greater in men than in women at 6 months only (P = .003). SAT was below predicted preoperatively in men and women and at 6 months and 1 year postoperatively in women (Figure 1D). Preoperatively, the SAT/SAT predicted ratio did not differ in men and women (P = .84). The proportion of subjects with SAT below vs above predicted values showed a trend to fall after surgery in men (80% to 33%) (P = .07), but not women (85% vs 40%)(P = .18). In men, the percent increase in SAT was less than that for VAT (P < .05), and the VAT/SAT ratio increased at 6 months (P = .047), 1 year (P = .006), and 2 years (P = .03). Women showed a trend for greater increases in VAT than SAT (P = .06).

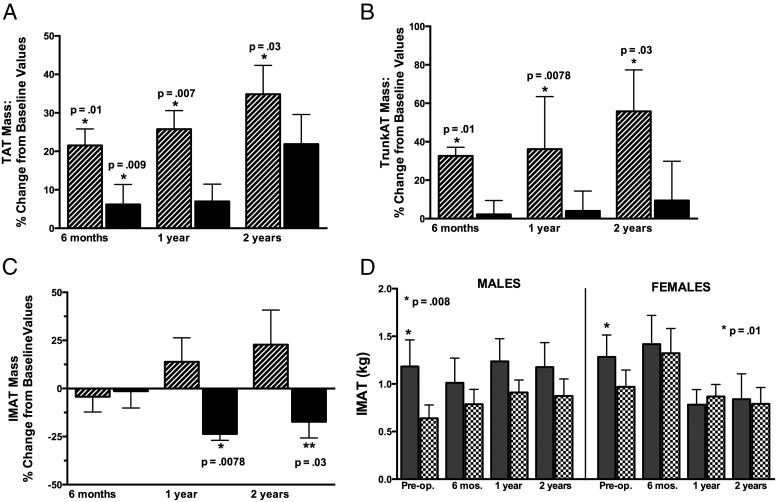

TAT

TAT rose in men and women after surgery (Figure 2A). TAT increased more in men than in women at 6 months (P = .0007) and 1 year (P = .017). Preoperatively, TAT was below the predicted value in 7 of 10 men and in 7 of 13 women and similar postoperatively (P = .42), and TAT did not differ from the predicted value (data not shown).

Figure 2.

A, Mean percent change in TAT mass (TAT = VAT + SAT + IMAT) from preoperative TAT mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (black bars). P values represent significance of changes from preoperative to postoperative follow-up. B, Mean percent change in trunk AT mass (trunk AT = VAT + trunk SAT + trunk IMAT) from preoperative trunk AT mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (solid black bars). P values represent significance of change from preoperative to postoperative follow-up. C, Mean percent change in IMAT mass from preoperative IMAT mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (black bars). P values represent significance of change from preoperative to postoperative follow-up. D, Mean IMAT mass in male (left) and female (right) subjects with acromegaly (shaded bars) compared with predicted values (patterned bars) preoperatively and at follow-up after surgery. P values compare acromegaly with predicted values.

Trunk AT

Trunk AT increased in men after surgery (Figure 2B). The percent trunk AT increase was greater in men than in women at 1 year (P = .003) and 2 years (P = .018). There was a trend for the limb/trunk AT ratio to decrease in men after surgery (P = .07), and this was primarily reflective of a change in the upper limb/trunk fat ratio (17.5% to 13.6%, P = .06).

IMAT

IMAT did not change in men but decreased after surgery in women (Figure 2C). The change in IMAT differed in men vs women at 12 months (P = .0057) and 2 years (P = .05). The changes in IMAT did not correlate with the changes in HOMA scores in men or women. IMAT was above predicted values preoperatively in men (average 147% above) and in women (average 34% above) (Figure 2D). The proportions of subjects with IMAT mass above vs below predicted values preoperatively and postoperatively were 100% and 80% in men (P = .33) and 70% and 50% in women (P = .17). The IMAT/TAT ratio was lower than that preoperatively at 6 months (P = .04), but not at 1 or 2 years postoperatively.

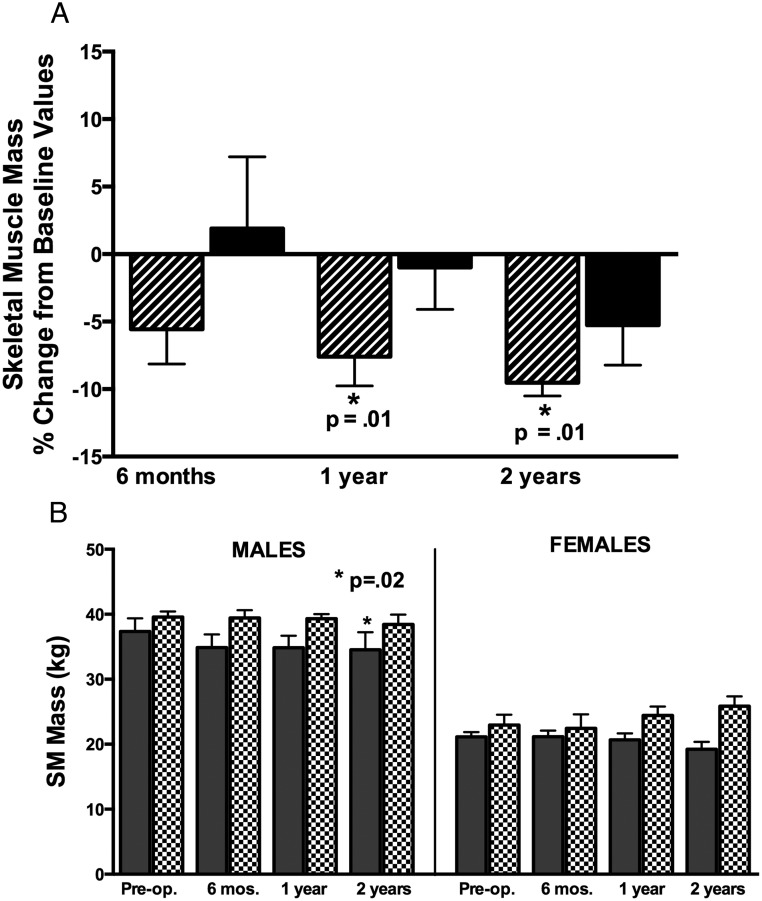

SM

SM was lower in men at 1 and 2 years postoperatively (Figure 3A). The change in SM after surgery did not differ in men and women. SM did not differ from predicted values in men or women preoperatively but was lower than the predicted value in men at 1 year (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A, Mean percent change in SM mass from preoperative SM mass at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery in men (striped bars) and women (black bars). P values represent significance of change from preoperative to postoperative follow-up. B, Mean SM mass in male (left) and female (right) subjects with acromegaly (shaded bars) compared with predicted values (patterned bars) preoperatively and at follow-up after surgery. P values compare acromegaly with predicted values.

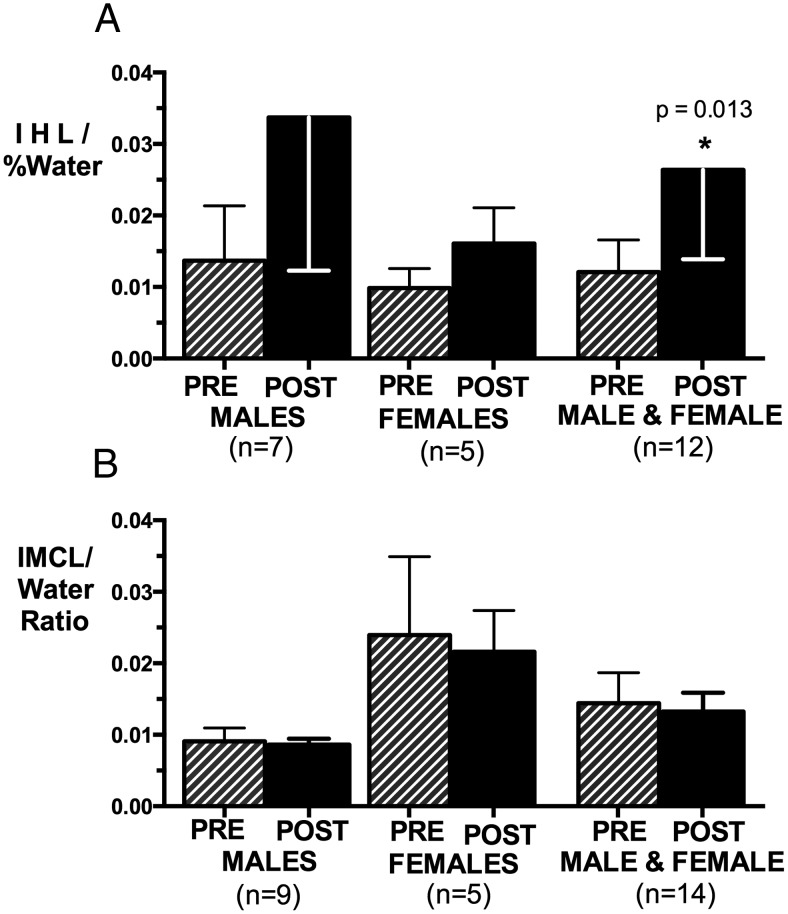

IHL and IMCL

IHL rose in men and women combined (P = .013) (Figure 4A). In this subgroup, VAT increased by 76 ± 64%. The percent increases in IHL and VAT did not correlate. IMCL did not change significantly after surgery (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Mean IHL (A) and IMCL (B) in men, women, and men and women combined before and at 1 year postoperatively. IHL increased significantly from preoperative levels in men and women combined (P = .013).

Endocrine, metabolic, and CV risk markers

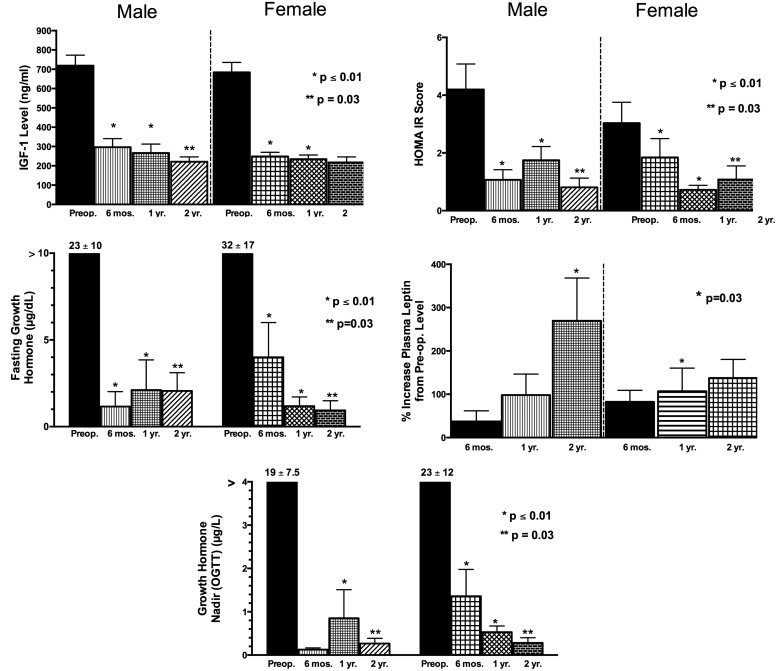

IGF-I, GH, HOMA, and composite insulin sensitivity index decreased and CRP and leptin increased after surgery (Table 1 and Figure 5). By 6 months after surgery 8 of 10 men and 11 of 13 women had an IGF-I level within their age-adjusted normal range, and the remainder had persistently elevated IGF-I levels ranging from 1.12 to 1.8 times the upper limit of normal. Preoperative and postoperative levels of IGF-I, fasting and nadir GH levels, or changes in these levels from preoperatively to postoperatively did not differ in men and women. Increases in VAT mass (and similarly SAT) correlated with the fall in fasting GH (r = −0.718, P < .001) and nadir GH (r = −0.755, P < .001) but not IGF-I (P = .23). The fall in the HOMA score correlated with increases in SAT (r = −0.369, P = .01) and VAT (r = −0.376, P = .009). Thus, an increase in VAT was associated with a decline in insulin resistance. Changes in leptin levels and changes in VAT or SAT with surgery did not correlate.

Figure 5.

Mean IGF-I levels, fasting GH levels, OGTT nadir GH levels, HOMA for insulin resistance (HOMA IR) score, and percent increase in leptin levels from preoperative to 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. P values represent significance compared with preoperative levels.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that active acromegaly and its treatment are characterized by a unique pattern of change in body composition and metabolism: specifically, lower VAT mass yet higher IMAT with insulin resistance in active acromegaly and after surgery an increase in central adiposity, both VAT and IHL, with a reduction in insulin resistance. This pattern was observed in men and women although VAT and SAT changes were more marked in men. IMAT decreased after surgery in women only. The unique body composition pattern of acromegaly may represent a type of lipodystrophy in which the modulation of AT metabolism by GH leads to adipose tissue redistribution. We observed sex differences in both the extent and pattern of recovery of this lipodystrophy.

A marked rise in VAT mass occurs after surgery for acromegaly in both men and women. The posttreatment rise may be a VAT reexpansion because VAT was lower than predicted preoperatively. Reduced fat mass is reported in active acromegaly (2, 4, 7, 10) and ascribed to GH's modulation of fat metabolism and potent lipolytic effect (13, 14). Body composition assessment by traditional techniques such as the 4-compartment model, bioimpedance, or DXA shows reduced total and trunk fat in active acromegaly that increase after therapy (2, 15–19). Only 1 prior study, however, prospectively examined masses of specific AT compartments in surgically treated patients (7). In this study of 15 patients, VAT volume by computed tomography increased in men, but not in women 1 year after surgery (7). In our study, VAT increased in men by 6 months and remained above preoperative values up to 2 years after surgery. We also provide novel evidence of a significant increase in VAT in women by 6 months that persisted through 2 years after surgery. The VAT increase related to the GH level decrease. In other studies, body composition changes correlated with those of GH and IGF-I (2, 18). We found greater changes in VAT than in SAT in men and women. GH's preferential effects on VAT may result from a predominance in VAT of those lipolytic pathways enhanced by GH such as β-adrenergic–dependent lipolysis (20–22) and GH's suppression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity (23), which is more concentrated in VAT (24). Pegvisomant therapy also preferentially increased intra-abdominal fat mass (25). Our finding of increases in the relative amounts of VAT to SAT support a predominance of VAT changes with acromegaly treatment. Interestingly, the VAT/SAT ratio decreased with GHRH therapy of HIV central adiposity (26), further evidence that this AT redistribution pattern relates to GH changes.

A sex difference in fat mass changes with acromegaly treatment is apparent from our study; men had greater VAT and SAT increases than women. In cross-sectional studies, however, deviations of the AT mass from predicted or control values were similar in men and women with active acromegaly (4, 15), consistent with our preoperative data. It is unclear whether the greater increase in AT mass after surgery in men represents greater AT sensitivity to postoperative GH lowering or a recovery from a greater reduction of AT mass in active disease, even though the latter has not been shown to date. Men are more sensitive to GH than women with regard to IGF-I production and may be more sensitive to GH in AT (27). Sex steroid effects, alternatively, may play a role in lessening the AT rise in women (24, 27). Men have a VAT mass that is higher and that represents a greater proportion of their total adiposity than women (24). Differences in adipocyte cell size and number by body region and sex also exist (24). Thus, sex differences in AT biology in combination with depot-selective lipolytic effects of GH (20–22) may be responsible for the observed sex differences in AT change postoperatively. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms for these observations.

A unique finding of this study is that IHL increased by 1 year after surgical treatment of acromegaly. In a recent study, IHL was unchanged 6 months after surgery in 7 patients with acromegaly, but IHL was lower than that in healthy control subjects (1.2% vs 4.3%) (28). Collectively, these results suggest that in active acromegaly, IHL is low and rises when acromegaly is treated by surgery. VAT increased in patients who had an increase in IHL, suggesting that these may be related. In a cross-sectional study, IHL was up to 3-fold higher in 7 patients with acromegaly years after successful treatment than in control subjects (29), suggesting that IHL may be persistently increased in patients with acromegaly receiving treatment. Moreover, GH receptor blockade added to somatostatin analog therapy increased IHL (30). Other data support an influence of GH on IHL accumulation. Mice with liver-specific GH receptor deletion had hepatic steatosis (31), and liver fat was increased in patients with GH deficiency and reduced with GH therapy (32, 33). In our study, IHL was lower in the setting of insulin resistance, which contrasts with other populations in whom IHL correlated positively with insulin resistance (8). Further investigation into this apparent inverse relationship between GH status and IHL accumulation and its clinical relevance for patients with acromegaly, including during various treatments, as well as for patients with other GH disorders, is warranted.

This study confirms that GH excess is associated with greater than the predicted IMAT mass (10). IMAT correlates positively with insulin resistance in other populations (5, 34). Interestingly, although insulin resistance fell in both men and women, IMAT mass fell significantly after surgery only in women. Early after surgery, men had a reduction in the IMAT/TAT ratio, but by 1 year this increased again. Because IMAT strongly correlates with TAT mass (12), the large AT increases in men may have obscured the IMAT changes. In our study, IMCL did not change, which is in accord with a small cross-sectional study (29) and the lack of a change in IMCL when pegvisomant was added to somatostatin analog therapy (30). However, in healthy subjects, 8 days of high-dose GH increased IMCL on SM biopsy in association with insulin resistance development (35) and, as in other populations (36), IMCL correlated negatively with insulin sensitivity in a combined cohort of acromegaly and control subjects (29), suggesting a relationship of GH-induced insulin resistance in muscle with lipid accumulation in it. The findings that lipid uptake is increased in muscle in acromegaly (3) and antilipolysis along with GH administration reduces its effect on muscle insulin resistance (37) further support this relationship. Potentially, IMAT rather than IMCL contributes more to muscle insulin resistance in long-standing GH excess, but additional studies are necessary to investigate these relationships further.

This study confirms our prior findings that SM mass in active acromegaly does not differ from the predicted value (11), but now also shows that SM mass decreases in men after surgery. In 1 study, muscle volume decreased similarly in men and women after surgery (7), whereas in another body cell mass was unchanged with acromegaly treatment (18). In cross-sectional studies, DXA lean tissue mass was increased in active compared with remission acromegaly (15, 16) and greater in male subjects, but not female subjects, compared with that in control subjects (15). DXA lean tissue estimates, however, are influenced by the increased tissue hydration of acromegaly (4) and along with SM include measures of soft tissues and organs such that lean tissue mass may not necessarily change in parallel with SM mass. It is unclear why SM fell after surgery, but hypogonadism in our male subjects cannot explain this. Increased SM mass in men with active acromegaly may be present but not yet recognized. Androgens may act synergistically with IGF-I to increase SM mass. In hypopituitary men, administration of GH and testosterone had independent and additive effects to suppress protein oxidation and stimulate protein synthesis (38, 39). Additional studies in a larger cohort may be necessary to detect increased SM mass in men with active acromegaly.

Our data suggest that acromegaly presents a unique pattern of AT distribution and its relationship to insulin resistance. In other populations, increasing central adiposity trends with increasing insulin resistance and vice versa. In healthy subjects, muscle fat content correlates with insulin resistance independently of total and visceral adiposity (40), so increased IMAT in acromegaly could contribute to insulin resistance, potentially increasing CV risk independently of VAT. A larger study will be necessary to examine this question and the relative contributions of AT depots to metabolic abnormalities and CV risk. Interestingly, VAT seemed to rise above the predicted value after surgery in men, suggesting a possible exaggerated increase. Hypopituitarism in our study cannot explain this, and metabolic or CV risk markers did not deteriorate up to 2 years postoperatively, but longer follow-up is needed to further examine the significance of this observation. The body composition changes observed in the 12 subjects followed out to 2 years postoperatively are consistent with those in the larger group. Because VAT mass is importantly linked to CV risk in other populations, understanding the determinants of the VAT increase and potential differences between treatments with regard to VAT changes is important to optimizing the long-term outcome in acromegaly.

Our study's strengths include its combined assessments of total body AT distribution, IHL, and IMCL and our comparison to predicted values accounting for height, weight, age, sex, and race. Predictive model utilization is advantageous because increased height and weight in acromegaly (4) make standard matching to control subjects for age and sex unreliable. A limitation of our study is that we cannot exclude the possibility that the relatively small sex-specific groups for some outcomes we examined influenced the results.

In conclusion, the body composition changes of acromegaly may represent those of an acromegaly-specific lipodystrophy driven by reduced AT storage in VAT and SAT depots with excess lipid deposition in muscle, but not liver. Our findings suggest sex-specific recovery from this lipodystrophy. Additional studies are needed to examine these differences and their clinical significance further. These data have implications for understanding the effects of GH on body composition and metabolic abnormalities in acromegaly as well as with GH use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Read for assistance with MRS acquisition and Mark Punyanitya for assistance with MRI reading.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01 DK 064720 and K24 DK 073040 to P.U.F.) and in part by the National Center for Research Resources/National Institutes of Health (Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant UL1 RR 024156 to Columbia University), the National Cancer Institute (Grant R01 CA118559 to F.A.-M.), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grants P30-DK26687 and P01-DK42618 to the New York Obesity Research Center).

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with clinical trial registration number NCT01809808.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AT

- adipose tissue

- CV

- cardiovascular

- DXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- HOMA

- homeostasis model assessment

- IHL

- intrahepatic lipid

- IMAT

- intermuscular adipose tissue

- IMHL

- intramyocellular lipid

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

- magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- SAT

- subcutaneous adipose tissue

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- TAT

- total adipose tissue

- VAT

- visceral adipose tissue.

References

- 1. Ho KK, O'Sullivan AJ, Hoffman DM. Metabolic actions of growth hormone in man. Endocr J. 1996;43(suppl):S57–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Sullivan AJ, Kelly JJ, Hoffman DM, Freund J, Ho KK. Body composition and energy expenditure in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Møller N, Schmitz O, Jørgensen JO, et al. Basal- and insulin-stimulated substrate metabolism in patients with active acromegaly before and after adenomectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bengtsson BA, Brummer RJ, Eden S, Bosaeus I. Body composition in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1989;30:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Kelley DE. Thigh adipose tissue distribution is associated with insulin resistance in obesity and in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abate N. Insulin resistance and obesity. The role of fat distribution pattern. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:292–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brummer RJ, Lönn L, Kvist H, Grangård U, Bengtsson BA, Sjöström L. Adipose tissue and muscle volume determination by computed tomography in acromegaly, before and 1 year after adenomectomy. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shulman GI. Ectopic fat in insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiometabolic disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2237–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reyes-Vidal C, Fernandez JC, Bruce JN, et al. Prospective study of surgical treatment of acromegaly: effects on ghrelin, weight, adiposity, and markers of CV Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4124–4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freda PU, Shen W, Heymsfield SB, et al. Lower visceral and subcutaneous but higher intermuscular adipose tissue depots in patients with growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I excess due to acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2334–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Freda PU, Shen W, Reyes-Vidal CM, et al. Skeletal muscle mass in acromegaly assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and dual-photon x-ray absorptiometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2880–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gallagher D, Kuznia P, Heshka S, et al. Adipose tissue in muscle: a novel depot similar in size to visceral adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jørgensen JO, Møller L, Krag M, Billestrup N, Christiansen JS. Effects of growth hormone on glucose and fat metabolism in human subjects. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simsolo RB, Ezzat S, Ong JM, Saghizadeh M, Kern PA. Effects of acromegaly treatment and growth hormone on adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:3233–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sucunza N, Barahona MJ, Resmini E, et al. Gender dimorphism in body composition abnormalities in acromegaly: males are more affected than females. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madeira M, Neto LV, de Lima GA, et al. Effects of GH-IGF-I excess and gonadal status on bone mineral density and body composition in patients with acromegaly. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:2019–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tominaga A, Arita K, Kurisu K, et al. Effects of successful adenomectomy on body composition in acromegaly. Endocr J. 1998;45:335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bengtsson BA, Brummer RJ, Eden S, Bosaeus I, Lindstedt G. Body composition in acromegaly: the effect of treatment. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1989;31:481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaji H, Sugimoto T, Nakaoka D, Okimura Y, Abe H, Chihara K. Bone metabolism and body composition in Japanese patients with active acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2001;55:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richelsen B. Action of growth hormone in adipose tissue. Horm Res. 1997;48(suppl 5):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffstedt J, Arner P, Hellers G, Lönnqvist F. Variation in adrenergic regulation of lipolysis between omental and subcutaneous adipocytes from obese and non-obese men. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:795–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Richelsen B, Pedersen SB, Møller-Pedersen T, Bak JF. Regional differences in triglyceride breakdown in human adipose tissue: effects of catecholamines, insulin, and prostaglandin E2. Metabolism. 1991;40:990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomlinson JW, Crabtree N, Clark PM, et al. Low-dose growth hormone inhibits 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 but has no effect upon fat mass in patients with simple obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2113–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tchernof A, Després JP. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:359–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Plöckinger U, Reuter T. Pegvisomant increases intra-abdominal fat in patients with acromegaly: a pilot study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koutkia P, Canavan B, Breu J, Torriani M, Kissko J, Grinspoon S. Growth hormone-releasing hormone in HIV-infected men with lipodystrophy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho KK, Gibney J, Johannsson G, Wolthers T. Regulating of growth hormone sensitivity by sex steroids: implications for therapy. Front Horm Res. 2006;35:115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winhofer Y, Wolf P, Krššák M, et al. No evidence of ectopic lipid accumulation in the pathophysiology of the acromegalic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4299–4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szendroedi J, Zwettler E, Schmid AI, et al. Reduced basal ATP synthetic flux of skeletal muscle in patients with previous acromegaly. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Madsen M, Krusenstjerna-Hafstrøm T, Møller L, et al. Fat content in liver and skeletal muscle changes in a reciprocal manner in patients with acromegaly during combination therapy with a somatostatin analog and a GH receptor antagonist: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1227–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fan Y, Menon RK, Cohen P, et al. Liver-specific deletion of the growth hormone receptor reveals essential role of growth hormone signaling in hepatic lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19937–19944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takahashi Y, Iida K, Takahashi K, et al. Growth hormone reverses nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a patient with adult growth hormone deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takano S, Kanzaki S, Sato M, Kubo T, Seino Y. Effect of growth hormone on fatty liver in panhypopituitarism. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:537–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albu JB, Kenya S, He Q, et al. Independent associations of insulin resistance with high whole-body intermuscular and low leg subcutaneous adipose tissue distribution in obese HIV-infected women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krag MB, Gormsen LC, Guo Z, et al. Growth hormone-induced insulin resistance is associated with increased intramyocellular triglyceride content but unaltered VLDL-triglyceride kinetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E920–E927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krssak M, Falk Petersen K, Dresner A, et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia. 1999;42:113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nielsen S, Møller N, Christiansen JS, Jørgensen JO. Pharmacological antilipolysis restores insulin sensitivity during growth hormone exposure. Diabetes. 2001;50:2301–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gibney J, Wolthers T, Johannsson G, Umpleby AM, Ho KK. Growth hormone and testosterone interact positively to enhance protein and energy metabolism in hypopituitary men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E266–E271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johannsson G, Gibney J, Wolthers T, Leung KC, Ho KK. Independent and combined effects of testosterone and growth hormone on extracellular water in hypopituitary men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3989–3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Diabetes. 1997;46:1579–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]