Abstract

Purpose

The landscape of managing potential conflicts of interest (COIs) has evolved substantially across many disciplines in recent years, but rarely are the issues more intertwined with financial and ethical implications than in the health care setting. Cancer care is a highly technologic arena, with numerous physician-industry interactions. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recognizes the role of a professional organization to facilitate management of these interactions and the need for periodic review of its COI policy (Policy).

Methods

To gauge the sentiments of ASCO members and nonphysician stakeholders, two surveys were performed. The first asked ASCO members to estimate opinions of the Policy as it relates to presentation of industry-sponsored research. Respondents were classified as consumers or producers of research material based on demographic responses. A similar survey solicited opinions of nonphysician stakeholders, including patients with cancer, survivors, family members, and advocates.

Results

The ASCO survey was responded to by 1,967 members (1% of those solicited); 80% were producers, and 20% were consumers. Most respondents (93% of producers; 66% of consumers) reported familiarity with the Policy. Only a small proportion regularly evaluated COIs for presented research. Members favored increased transparency about relationships over restrictions on presentations of research. Stakeholders (n = 264) indicated that disclosure was “very important” to “extremely important” and preferred written disclosure (77%) over other methods.

Conclusion

COI policies are an important and relevant topic among physicians and patient advocates. Methods to simplify the disclosure process, improve transparency, and facilitate responsiveness are critical for COI management.

INTRODUCTION

The integrity of the medical profession depends on the ethical values displayed when physicians interact with patients, colleagues, and the public. Physician-industry relationships have long been part of oncology research and practice. These relationships have recently experienced a surge in public interest, owing to media and government inquiries about influences on physicians' professional judgment.1,2 Several high-profile investigations led academic institutions and professional medical organizations to adopt policies governing physician-researchers' relationships with industry3–5 and set the stage for enactment of the Physician Payments Sunshine Act,6 which will require public reporting of industry payments to physicians.

In the health care setting, a conflict of interest (COI) is a financial or professional stake that compromises a physician's or researcher's objective professional judgment. Financial or professional relationships do not necessarily constitute COIs, but relationships involving financial reward have the potential to give rise to COIs in almost any aspect of patient care and medical research. COIs have the potential to affect how information is presented in scientific journals and medical education forums.7,8 As a result, many medical professional organizations, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), have COI policies in place to address the industry relationships held by authors, presenters, and others who control the content of published and presented information.9–13 In general, these policies rely on voluntary self-disclosure of relationships that could be viewed as COIs.

There is no consensus on how best to define, disclose, and manage potential COIs. Policies and regulations have implemented a range of disclosure requirements, management strategies, and restrictions. A recent commentary in Chest concluded that self-disclosure alone is insufficient to manage COIs.14 However, policies of recusal and restriction were viewed as difficult to employ fairly, whereas enhanced third-party awareness and evaluation were viewed as critical for success. Ultimately, there remains no set standard among medical associations, academic institutions, publishers, or other entities about how to identify and manage COIs. Leaders at the Institute of Medicine, the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, and other organizations continue to revise recommendations.15,16

Given the unique role of professional medical organizations in identifying and managing potential COIs, particularly in research, members of the ASCO Leadership Development Program (LDP)17 undertook a project to evaluate the ASCO COI Policy (Policy),9 which was at that time undergoing a process of revision, scheduled for release in 2013. Currently, the Policy focuses on the principal investigators of clinical trials and restricts these individuals from presenting research at ASCO meetings or publishing in ASCO journals if they receive or hold: (1) stock or equity in a trial sponsor; (2) royalties or licensing fees from the product or treatment under investigation; (3) travel or trips paid by the trial sponsor to attend educational or scientific meetings; (4) honoraria or gifts from the trial sponsor; (5) research-related payments substantially exceeding actual research costs; or (6) position as an officer, board member, or employee of the sponsor.11 Exceptions are made on a case-by-case basis. Certain restrictions also apply to the ASCO president, president elect, immediate past president, chief executive officer, and editors-in-chief of Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO) and Journal of Oncology Practice and a majority of members of panels involved in guideline development. The LDP considered whether the Policy was relevant to the current research environment, user friendly, and sufficiently rigorous to withstand public scrutiny. A survey explored ASCO members' perceptions about the Policy and management strategies. To assess the perceptions of nonphysician stakeholders concerning COIs, a second survey was directed to patients with cancer, survivors, family members, and patient advocates. The scope of the surveys was limited to examination of the Policy as it relates to individuals who present, produce, or discuss data in publications or symposia.

METHODS

Member Survey

An online survey, using the Zoomerang survey tool (http://www.zoomerang.com), was offered to ASCO members in membership categories of active or active junior. The questions were developed during several face-to-face meetings and conference calls among the authors, consultation with survey experts, and test-question piloting with other LDP members. ASCO board members, committee members, and staff were excluded from the contact list. The final survey distribution list contained 19,238 contacts. Members were solicited by e-mail communication, with two reminders. The survey was available for 3 weeks in December 2010 to January 2011. Responses were voluntary and anonymous and recorded using a Likert scale, with optional narrative comments permitted.18 The survey was designed to address three primary goals: (1) assess the degree to which members were aware of the Policy; (2) determine satisfaction with the Policy rigor; and (3) establish how members felt COIs were best managed. Consent for participation in the survey was implied by response and therefore institutional review board exempted.

On the basis of self-reported activities (publication, presentation, session chair, and so on), respondents were identified as consumers or producers of scientific material. Survey respondents were asked to report if, in the last 3 years, they had published an article in a peer-reviewed journal (regardless of authorship position), submitted an abstract to an oncology meeting, participated as a discussant for an oncology meeting, or chaired a scientific session. Individuals who responded yes to any of those criteria were coded as producers; all other respondents were labeled as consumers. The questions posed to the two groups were similar in content but were worded differently to address the respective roles.

Stakeholder Survey

This survey was directed to an ASCO distribution list of 483 individuals. The survey was conducted online using the Zoomerang survey tool, with Likert-scaled questions with optional narrative response. Responses were solicited by e-mail, and the survey was available for 2 weeks in April 2011. Recipients were encouraged to forward to the survey to friends, family, and others. The survey was designed to address three primary goals: (1) to what extent interaction between physicians and industry is viewed as affecting physician-patient relationships; (2) the context in which physician-researchers should disclose their industry relationships; and (3) the manner in which COI information is best conveyed. The survey included 11 questions based on those used in the member survey, adapted for a lay audience.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using OpenEpi software (http://www.openepi.com) reporting χ2 analysis, using a Fisher's exact test for P value estimation and a conditional maximum likelihood estimate odds ratio (OR) and mid-P exact test for upper and lower 95% CIs.

RESULTS

ASCO Member Survey Results

Demographics.

The COI survey was administered to ASCO active physician members and was open from December 28, 2010, to January 21, 2011. There were 1,967 member responses to the survey (1% of membership). Demographic data from the respondents are listed in Table 1. The majority of respondents (65%) had been ASCO members for more than 10 years, whereas 20% were 5- to 10-year members, and 15% had been members for fewer than 5 years. A vast majority of respondents (73%) were based in the United States, and only 11% reported employment by the pharmaceutical industry. Although a small representation, the demographics of survey respondents are representative of the ASCO active and active-junior membership as a whole. On the basis of voluntary responses to a panel of questions regarding research activities, 80% of the respondents described themselves as producers of scientific information or research content. The remaining 20% were classified as consumers of oncology content.

Table 1.

Demographic Data From Survey Respondents and Self-Designation As Consumer or Producer

| Demographic | All Respondents |

Consumers |

Producers* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Duration of ASCO membership, years | ||||||

| ≤5 | 290 | 15 | 43 | 11 | 247 | 16 |

| 6 to 10 | 390 | 20 | 55 | 14 | 335 | 21 |

| ≥10 | 1,287 | 65 | 292 | 75 | 997 | 63 |

| US based | 1,433 | 73 | 368 | 94 | 1,067 | 68 |

| Primary employment | ||||||

| Commercial | 209 | 11 | 37 | 9 | 172 | 11 |

| NonCommercial | 1,758 | 89 | 353 | 91 | 1,407 | 89 |

Abbreviation: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Designated based on self-identification as having published a peer-reviewed manuscript or oncology meeting abstract or served as discussant or chair at an oncology meeting session in prior 3 years.

Familiarity and use of Policy.

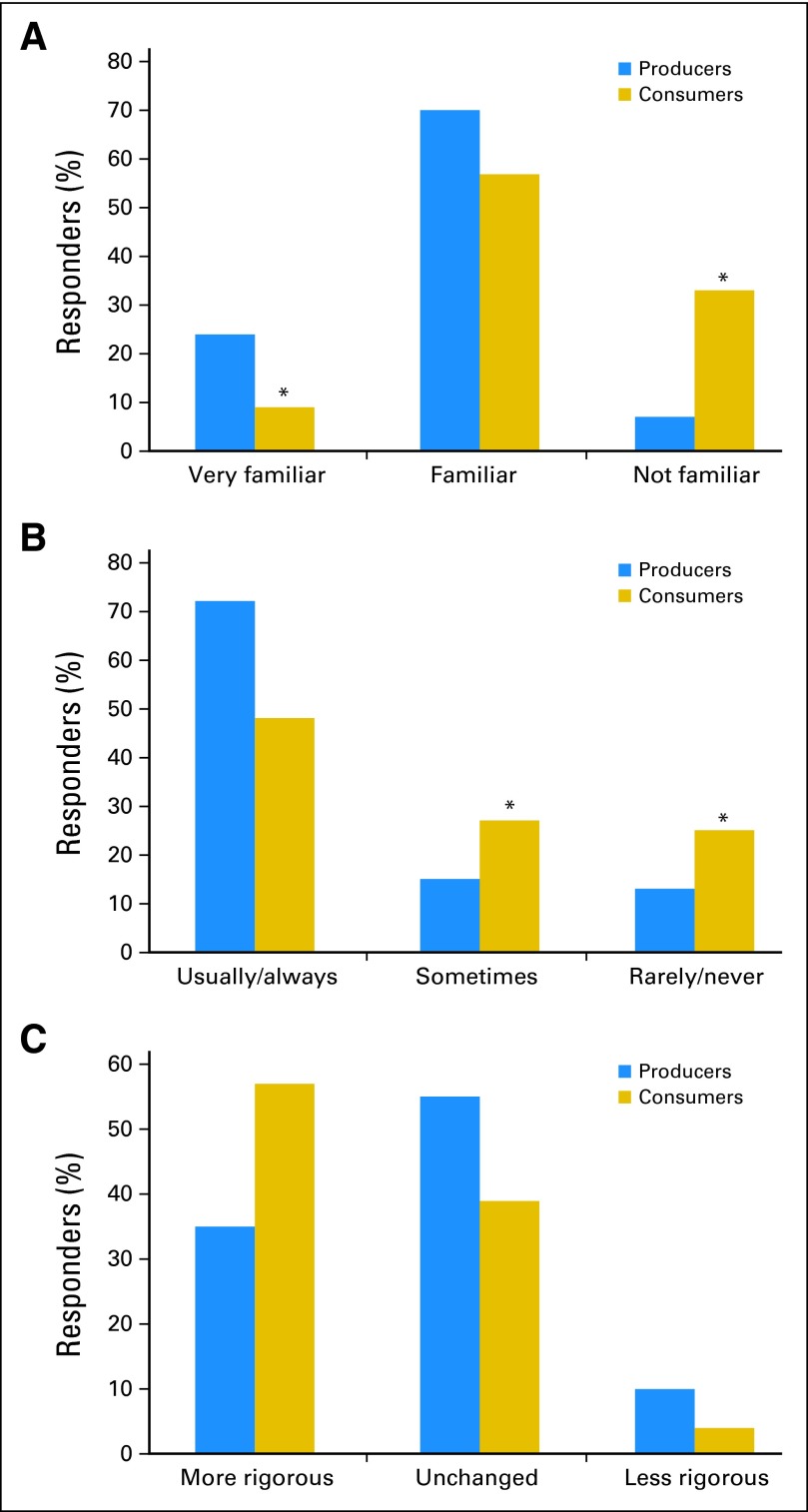

The majority of respondents (93% of producers; 66% of consumers) felt they were at least familiar with the Policy (Fig 1A). However, one third of consumers reported lack of familiarity with the Policy. Only 24% of producers indicated that they were “very familiar” with the policy. The accuracy of these self-assessments was not tested.

Fig 1.

American Society of Clinical Oncology member survey key responses. Members, categorized as producers or consumers of research data, were asked to indicate (A) their level of awareness of the existing conflict of interest (COI) policy, (B) how routinely COI information was reviewed in its currently provided format, and (C) the level of rigor that should be applied to a COI policy revision, relative to current standards. (*) P < .001.

Regarding use of the COI information reported by ASCO, a substantial proportion of both producers and consumers reported that they “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” evaluated COIs (Fig 1B). This group represented over 50% of consumers and over 20% of producers. The difference between the consumers and producers who responded in this manner was also highly significant (OR, 2.764; 95% CI, 2.199 to 3.475; P < .001). Thus, although substantial effort is expended to collect and curate COI data on the part of both the organization and individuals, roughly half of professionals, and in particular the consumer group, are relying on information presented, without routinely scrutinizing this information in the context of the Policy.

Types and degrees of COIs.

To assess whether ASCO members regarded different types of interaction as giving rise to more or less significant COIs (Table 2), members were asked to rate the so-called amount of conflict present in several common physician-industry interactions. Meals and uncompensated consulting were not viewed as creating significant COIs, whereas stock ownership and participation in speakers bureaus were consistently viewed as creating COIs. These views did not appreciably differ between consumers and producers.

Table 2.

Common Physician-to-Industry Interactions Where ASCO Members Indicated Concerning* Level of Conflict

| Type of Interaction | Respondents (%) |

|---|---|

| Payment for meals | 20 |

| Speakers bureau (slides provided) | 72 |

| Speaking honoraria (slides not provided) | 50 |

| Compensated consultation | 59 |

| Uncompensated consultation | 22 |

| Stock ownership | 81 |

Abbreviation: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Moderate to substantial conflict

The monetary value of an interaction was also assessed for relevance in perceptions of COIs. Any level of financial exchange was reported as problematic by 31% of respondents; 29% reported thresholds from $1,000 to $10,000 as problematic; 23% reported $10,000 to $50,000 as problematic; and 18% reported that relationships valued at $50,000 or $100,000 or those with no upper ceiling raised concerns.

Strategies to manage COIs.

The surveyed members indicated that COI management was an important issue to the organization and warranted significant rigor in its application (Fig 1C). There were numerical differences in this response between consumers and producers, with a larger fraction of consumers (57%) feeling that the Policy could be strengthened in rigor compared with only 35% of producers. This difference of opinion was also significant (OR, 0.4075; 95% CI, 0.3248 to 0.5106; P < .001), with more producers feeling that the Policy was sufficiently rigorous.

ASCO implements its Policy through a range of strategies, including restrictions on presentation or publication of clinical trial data. Table 3 summarizes views on which mechanisms for managing potential COIs are the most effective. Regardless of position as a consumer or producer, respondents found strategies involving transparency, public disclosure, peer review, external auditing, and presentation of alternative views as more effective measures for managing COIs, whereas restriction was considered less effective by nearly half of respondents.

Table 3.

ASCO Member Opinions on Effectiveness* of COI Management Strategies

| Strategy | Respondents (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Consumers | Producers | |

| Public disclosure | 81 | 77 |

| Peer review | 86 | 87 |

| Auditing of content | 85 | 83 |

| Alternative views presented | 91 | 88 |

| Restrictions on presenters | 58 | 54 |

Abbreviation: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; COI, conflict of interest.

Effective to extremely effective.

To address future strategies to effectively report and manage COIs, respondents were asked to select their choice from a list of options. A substantial proportion of individuals favored strategies that would increase visibility or transparency of interactions with pharmaceutical or industry vendors, but only a minority favored increasing restrictions on presentation by members with potential conflicts.

Subgroup analysis.

No consistent differences were detected between the responses in the preplanned membership subsets. These included United States versus international, industry employed versus nonindustry, and duration of membership.

Nonphysician Stakeholder Survey Results

Demographics.

The survey was administered to a distribution of nonphysician stakeholders, including patients with cancer, survivors, family members, and patient advocates whose contact information was available to ASCO. Recipients were encouraged to forward to the survey to like individuals or groups. The survey was open for responses from April 7-28, 2011. There were 264 completed surveys. Nearly half of respondents were age 40 to 60 years (47%), and slightly fewer were in the 60- to 80-year age range (41%). A majority of respondents (76%) were women, and 93% identified themselves as patients with cancer or survivors or family members of a patient with cancer.

Nonphysician stakeholder viewpoints on physician-researcher and industry partnerships.

When respondents were asked if the type of physician-industry interaction would affect how they viewed the relationship, 74% said yes. When asked if the dollar amount involved affected how they viewed the relationship, 58% of respondents said yes. Similar to the ASCO member survey, stakeholder survey respondents indicated a wide range of monetary thresholds that gave rise to COIs, with answers spread fairly evenly across the range from any threshold to more than $1 million. Also, in a close parallel to the responses of ASCO members, certain categories of physician-industry relationships, such as consulting for pharmaceutical companies, receiving company funding for clinical trials, or owning company stock, were more widely viewed as creatin

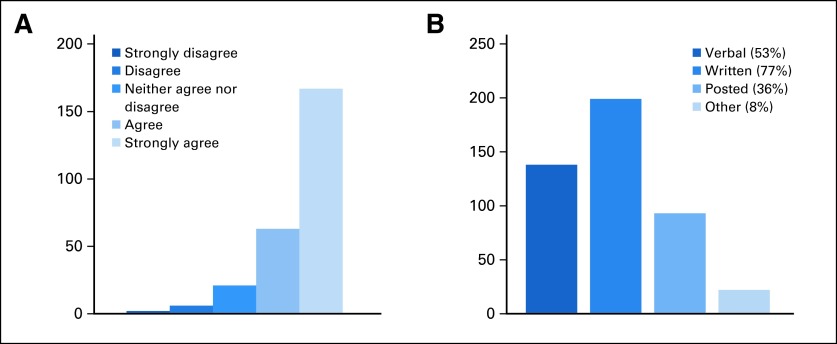

The consensus was that COI disclosure was “very important” to “extremely important” (Fig 2A) in all contexts, including the following: (1) among physician-researchers; (2) to patients of a physician-researcher; (3) to possible clinical trial participants; and (4) between physicians and their patients, even in the clinical care setting not involving a clinical trial. Unstructured comments indicated that full disclosure was expected and could be a contributing factor in decisions regarding therapy. Stakeholders indicated a wide range of opinions but were universal in their expectation that disclosures be shared freely among parties. Several comments were highly informative of the changing nature of COI disclosure outside the health care system, with respondents observing that such information was provided as a matter of course in other professional settings.

Fig 2.

Advocate and stakeholder survey key responses. Respondents were asked (A) whether information on physician compensation should be available to patients (asked for patients considering clinical trials and for any patient-physician encounters; data presented are for any patient-physician encounters) and (B) how such information would be best disclosed to patients (answers chosen from a series of options).

Finally, given the multiple constraints placed on physician-patient interactions and the priorities to discuss clinical, therapeutic, prognostic, and psychosocial issues during a time-limited encounter, stakeholders were asked how COI information could be best conveyed to patients and caregivers. Respondents favored written disclosure (77%) over other methods (Fig 2B), closely followed by verbal disclosure (53%).

DISCUSSION

Oncology is one of the most active areas for development of novel therapeutics. Oncologists in community practice and academia are frequently involved in drug-development research, leading to interactions and relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. Initially adopted in 1994, the ASCO COI Policy was developed to provide guidance for the disclosure of relationships and COI management in editorial and peer-review activity. The Policy has been regularly revised, with updates published in 1996, 2003, and 2006 in JCO and a comprehensive revision expected in early 2013.9–13,19 These versions of the Policy created restrictions on principal investigators engaging in potential COI relationships but also created situations in which exceptions were necessary or where subjective interpretation of the COI categories was possible. It is not clear if these policies led to changes in COI practices, but the Policy has brought issues of COI disclosure and management to a position as a key issue in oncology and medical practice.

In the context of the upcoming revision and the evolving societal concerns, an evaluation of the attitudes, perceptions, and expectations of physicians and nonphysician stakeholders was needed. Although COI management is important for all medical professionals, oncology care is a discipline where clinical practitioners are actively involved in the development of new therapies and is thus a unique brand of medicine combining extensive physician-industry relationships and intense physician-patient relationships. The primary intent of this evaluation was to determine how the ASCO COI Policy could rema

This survey was the first to our knowledge seeking to measure and compare the opinions of physicians, considered from the viewpoint of both producers (physicians reporting research findings with potential COIs) and consumers (physicians interpreting such data) as well as nonphysician stakeholders (including patients with cancer and family members). There are limitations that must be considered when evaluating these data. The sample represents only approximately 1% of the survey target population, and the sample population for both surveys was limited by the short duration of the survey and the solicitation method (ie, e-mail). Therefore, respondents may represent a subpopulation with heightened interest in this topic or other unmeasured motivation for completing the survey. Other sources of potential biases include lack of a validated study of attitudes toward COIs and reliance on self-reporting of knowledge of the current Policy as well as unintentional biases in development of questions and multiple-choice responses, the order in which the answer choices were presented, and limitations on the number of choices offered. With a self-administered survey, we were not able to explore the topic or evaluate responses in greater depth, as one might with focus groups or structured interviews. Even with an anonymous survey, perceived social desirability may guide responses rather than the respondents' true feelings regarding COIs.

Nevertheless, this represents an important, if not exhaustive, assessment of the ASCO COI Policy with multiple lessons. The majority of respondents valued comprehensive and rigorous disclosure of potential COIs in ASCO scientific and educational materials. Attitudes regarding COIs and physician-industry relationships differed according to the nature of the interaction and the amount of money involved. ASCO member respondents considered certain relationships as particularly associated with COIs, such as stock ownership and participation in speakers bureaus. Less concern about COIs was associated with other relationships, such as payment for meals and uncompensated consulting. Other activities were regarded as having moderate COI potential (paid consulting and industry-sponsored research activity). Although the level of compensation from industry was considered important by both ASCO members and nonphysician stakeholders, no consensus was evident regarding thresholds for unacceptable COIs. These results indicate that it may be useful to disc

A study finding that may help guide future changes to COI policy for medical organizations is the strong preference for consistent, transparent disclosure expressed by the majority of physician and stakeholder respondents in all categories. These sentiments are in contrast to the current environment where COI disclosure standards vary widely across the policies of institutions, societies, journals, and government entities. The clear message calling for reliable and accessible COI reporting was considered in recent revisions to the ASCO Policy.

Overall, the results of these surveys indicate that COI policy is an important and relevant topic among physicians, patients, and family members. While this topic has been the subject of significant media and government attention, interested parties still remain unaware of current COI policies and guidelines. Clear and consistent reporting standards will simplify the disclosure process, improve transparency, facilitate awareness, and reflect responsiveness to the modern era of COI management.

Acknowledgment

We thank the survey respondents for providing feedback on a difficult topic. We would also like to acknowledge valuable input from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Ethics Committee and the outstanding support of the ASCO staff to construct and conduct this survey. Finally, without the ASCO Leadership Development Program, this project would not have been possible.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Employment or Leadership Position: Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, GlaxoSmithKline (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: David H. Johnson, American Board of Internal Medicine (C), miRNA Therapeutics (C), Peloton Therapeutics (C); Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, Genentech (C) Stock Ownership: Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, GlaxoSmithKline Honoraria: None Research Funding: Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, Novartis Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: A. Craig Lockhart, Marcia S. Brose, Edward S. Kim, David H. Johnson, Dina L. Michels, Lynn M. Schuchter, W. Kimryn Rathmell

Administrative support: Dina L. Michels

Collection and assembly of data: A. Craig Lockhart, Marcia S. Brose, Edward S. Kim, David H. Johnson, Dina L. Michels, Courtney D. Storm, W. Kimryn Rathmell

Data analysis and interpretation: A. Craig Lockhart, Marcia S. Brose, Edward S. Kim, David H. Johnson, Jeffrey M. Peppercorn, Lynn M. Schuchter, W. Kimryn Rathmell

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson D. Medical industry ties often undisclosed in journals. New York Times. 2010. Sep 14, p. B1.

- 2.Berwick DM, Sebelius K. Transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register. 2011;76:78767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D. Harvard teaching hospitals cap outside pay. New York Times. 2010. Jan 3, p. A1.

- 4.Rothman DJ, Chimonas S. Academic medical centers' conflict of interest policies. JAMA. 2010;304:2294–2295. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. Conflicts of interest in research. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/coi/

- 6.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2009. H.R. 3590, § 6002.

- 7.Als-Nielsen B, Chen W, Gluud C, et al. Association of funding and conclusions in randomized drug trials: A reflection of treatment effect or adverse events? JAMA. 2003;290:921–928. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golder S, Loke YK. Is there evidence for biased reporting of published adverse effects data in pharmaceutical industry-funded studies? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society Of Clinical Oncology. Revised conflict of interest policy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:519–521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revisions of and clarifications to the ASCO conflict of interest policy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:517–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society Of Clinical Oncology. Revised conflict of interest policy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2394–2396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society Of Clinical Oncology policy statement. Oversight of clinical research. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2377–2386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society Of Clinical Oncology. Background for update of conflict of interest policy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2387–2393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin RS. The role of conflict of interest in reporting of scientific information. Chest. 2009;136:253–259. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC,: National Academy of Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Code for interactions with companies. http://www.cmss.org/codeforinteractions.aspx. [PubMed]

- 17.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Leadership Development Program. http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Education+%26+Training/Training/Leadership+Training/Leadership+Development+Program.

- 18.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson WB, Emanuel EJ. Physician-drug company conflict of interest. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:316–320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]