Abstract

The severity and longevity of the current Ebola outbreak highlight the need for a fast-acting yet long-lasting vaccine for at-risk populations (medical personnel and rural villagers) where repeated prime-boost regimens are not feasible. While recombinant adenovirus (rAd)-based vaccines have conferred full protection against multiple strains of Ebola after a single immunization, their efficacy is impaired by pre-existing immunity (PEI) to adenovirus. To address this important issue, a panel of formulations was evaluated by an in vitro assay for their ability to protect rAd from neutralization. An amphiphilic polymer (F16, FW ∼39,000) significantly improved transgene expression in the presence of anti-Ad neutralizing antibodies (NAB) at concentrations of 5 times the 50% neutralizing dose (ND50). In vivo performance of rAd in F16 was compared with unformulated virus, virus modified with poly(ethylene) glycol (PEG), and virus incorporated into poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) polymeric beads. Histochemical analysis of lung tissue revealed that F16 promoted strong levels of transgene expression in naive mice and those that were exposed to adenovirus in the nasal cavity 28 days prior to immunization. Multiparameter flow cytometry revealed that F16 induced significantly more polyfunctional antigen-specific CD8+ T cells simultaneously producing IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α than other test formulations. These effects were not compromised by PEI. Data from formulations that provided partial protection from challenge consistently identified specific immunological requirements necessary for protection. This approach may be useful for development of formulations for other vaccine platforms that also employ ubiquitous pathogens as carriers like the influenza virus.

Keywords: formulation, pre-existing immunity, adenovirus serotype 5, Ebola virus, nasal vaccine, multifunctional CD8+ T cell response

Introduction

Since the resolution of the Plague of Athens in 426 B.C., it has been understood that exposure to microorganisms that cause disease is protective against reinfection.1 This concept of immunity through exposure to pathogens provided the foundation for early vaccine development, which has led to the control of several major diseases including smallpox, diphtheria, tetanus, yellow fever, pertussis, and poliomyelitis.2 Within the past 20 years, advances in synthetic and systems biology have significantly compressed the time between identification of a pathogen responsible for a pandemic and global dispersement of an effective vaccine.3 This technological revolution has also fostered production of highly sophisticated vaccine platforms consisting of recombinant viruses, virus like particles, synthetic protein antigens, polysaccharide conjugates, and human cell isolates.4 Despite this progress, vaccines continue to be produced primarily as injectable products.

Administration of drugs within the nasal cavity was first exploited to alleviate respiratory conditions such as allergic and infectious rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and sinusitis.5 Further understanding of the rich vascularization and active transport regions along the nasal mucosa has made it an attractive site of delivery for small molecule compounds that are subject to extensive first pass metabolism when given orally.6 The presence of specialized mucosal lymphoid follicles throughout the nasal mucosa, coupled with the fact it is often the place at which most bacterial and viral infections are initiated,7 suggests that intranasal immunization is a logical approach for protection against many pathogens. However, reported cases of anaphylaxis and development of neurological side effects after nasal administration of vaccines have prevented intranasal delivery technology from being exploited to its full potential.8 To date, only three intranasal vaccines have been approved for human use: FluMist in the United States,9 Fluenz in the European Union,10 and Nasovac, a pandemic H1N1 vaccine approved by the Drug Controller General of India.11

We have utilized nasal delivery of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5-based vaccine against the Ebola virus (formerly Zaire ebolavirus) as a method to improve vaccine performance in the presence of pre-existing immunity (PEI) to the adenovirus vector. This delivery method fosters very high, localized, and notable systemic immune responses to an encoded antigen and, more specifically, has fully protected animals with PEI to adenovirus from lethal challenge with Ebola.12,13 However, we have found that, if prior exposure to adenovirus occurs in the respiratory tract in a manner similar to natural infection, multifunctional CD8+ T cells and antigen-specific antibody responses are compromised in mouse and guinea pig models of Ebola infection.14 Some of these responses are starting to be observed in the clinic.15 Both of these responses have been found to support protection from Ebola in rodent and primate models of disease.14,16,17 This finding prompted us to adopt the hypothesis that reinvigoration of these responses through the use of relatively nontoxic compounds that increase residence time in the nasal cavity and improve bioavailability of the vaccine beyond the epithelial barrier would significantly improve vaccine potency in those with prior exposure to adenovirus. Reagents selected for this purpose fell into four major categories: sugars and sugar derivatives (sucrose, melezitose, raffinose), surfactants (Pluronic F68, N-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (nDMPS)), polymers (poly(ethylene) glycol, poly(lactide-co-glycolide), poly(maleic anhydrides)), and permeability enhancers (sorbitol, mannitol). Formulation candidates were evaluated in a graded, stepwise manner. Preparations that improved transduction efficiency with minimal cytotoxic effects in an in vitro model of the airway epithelium were selected for further testing in vivo in rodent models of Ebola virus infection.

Experimental Section

Materials

Acepromazine was purchased from Fort Dodge Laboratories (Atlanta, GA). Ketamine was purchased from Wyeth, Fort Dodge, Animal Health (Overland Park, KS). Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), xylazine, tresyl chloride activated monomethoxypoly(ethylene)glycol, l-lysine, poly(ethylene) glycol 3000, ethyl acetate, poly(lactide-co-glycolide) copolymers (PLGA, 50:50 lactide:glycolide), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), glutaraldehyde (grade I, 25% in water), o-phenylenediamine, sucrose (USP grade), d-mannitol (USP grade), d-sorbitol (USP grade), bovine serum albumin (RIA grade), brefeldin A, potassium ferricyanide, and potassium ferrocyanide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Eosin Y and Tween 20 were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Kalamazoo, MI, and Pittsburgh, PA respectively). Melezitose monohydride was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH) and raffinose pentahydrate from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Sodium hydroxide, potassium phosphate monobasic, potassium phosphate dibasic, and sodium dodecyl sulfate were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ). Pluronic F68 was purchased from BASF (Mount Olive, NJ). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), RPMI-1640, minimal essential medium (MEM), and l-glutamine were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA). Fetal bovine serum (qualified, US origin), penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Sodium pyruvate and nonessential amino acids were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-gal) was purchased from Gold Biotechnology (St. Louis, MO). N-Dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (nDMPS), poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-decene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (PMAL C8, formula weight (FW) 8,500), poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-tetradecene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (PMAL C12, FW 12,000), and poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (PMAL C16, FW 39,000) were purchased from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). The TELRTFSI peptide was purchased from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). The negative control peptide (YPYDVPDYA) was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). Antibodies used for ELISPOT and flow cytometry, Cytofix/Cytoperm and Perm/Wash reagents were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Adenovirus Production

Four different recombinant adenoviruses were used in the studies outlined in this manuscript. All were first generation E1/E3 deleted recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vectors that differed only by transgene expression cassettes. Two vectors, AdlacZ, expressing Escherichia coli beta-galactosidase, and AdGFP, expressing green fluorescent protein, were used for rapid screening of the transduction efficiency of formulations in vitro and in vivo due to the ease by which their transgene products could be visualized and quantitated. AdNull, an E1/E3 deleted adenovirus 5 vector with a similar genetic backbone as the other viruses used in this study except that it does not contain a marker transgene expression cassette, was used to induce pre-existing immunity to adenovirus 5 in mice prior to immunization. These viruses were each amplified in HEK 293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573 Manassas, VA). They were purified from cell lysates by banding twice on cesium chloride gradients and desalted over Econo-Pac 10 DG disposable chromatography columns (BioRad, Hercules, CA) equilibrated with potassium phosphate buffer (KPBS, pH 7.4). The concentration of each preparation was determined by UV spectrophotometric analysis at 260 nm and by an infectious titer assay as described.18 Preparations with a ratio of infectious to physical particles of 1:100 were used for these studies. For immunization and challenge studies, an E1/E3 deleted recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vector expressing a codon optimized full-length Ebola glycoprotein sequence under the control of the chicken β-actin promoter (Ad-CAGoptZGP) was amplified in HEK 293 cells and purified as described.14 Concentration of this and AdNull was determined by UV spectrophotometric analysis at 260 nm and with the Adeno-X Rapid Titer Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Preparations with infectious to physical particle ratios of 1:200 of each of these viruses were used in this study.

PEGylation of Adenovirus

PEGylation was performed according to established protocols.19,20 Characterization of these preparations revealed significant changes in the biophysical properties of the virus such as the PEG-dextran partition coefficient and peak elution times during capillary electrophoresis.20 Approximately 18,245 ± 546 PEG molecules were associated with each virus particle in the studies outlined here as determined by a PEG-biotin assay.21

PLGA Microspheres

PLGA microspheres were prepared using a standard water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) double emulsion and solvent evaporation method.22 One milliliter of virus (5 × 1012 virus particles) was added to ethyl acetate containing 100 mg of PLGA. The primary water-in-oil emulsion was prepared by homogenization for 30 s and was then added to 10 mL of an aqueous solution containing 5% (w/v) PVA. The secondary W/O/W emulsion was prepared by homogenization for 60 s and further agitated with a magnetic stirring rod for 2 h at 4 °C to evaporate the cosolvent. Microspheres were collected by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 3 min and washed five times with sterile KPBS. The diameter of the microspheres fell between 0.3 and 5 μm with an average particle size of 2.06 ± 1.4 μm as determined by dynamic light scattering using a DynaPro LSR laser light scattering device and detection system (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). Regularization histograms and assignment of hydrodynamic radius values to various subpopulations within the sample were calculated using DynaLS software (Wyatt). The amount of virus embedded in the microspheres was determined by digesting a portion of each preparation with 1 N NaOH for 24 h. The average encapsulation efficiency of this process was 21.6 ± 4.4% (n = 6). Aliquots of each preparation were dried, placed in sterile, light resistant containers, and stored at room temperature for evaluation of stability over time. Release profiles of each preparation were determined by placing 10 mg of microspheres in 0.5 mL of sterile KPBS on a magnetic stir plate (Corning, Tewksbury, MA) in a 37 °C incubator. Each day, microspheres were collected by centrifugation, and the supernatant was collected and replaced with KPBS prewarmed to 37 °C. The number of infectious virus particles released from microspheres was determined by serial dilution of collected samples and subsequent infection of Calu-3 cells (ATCC, HTB-55), an established model of the airway epithelia.23

In Vitro Screening of Formulations

Two vectors, AdlacZ, expressing E. coli beta-galactosidase, and AdGFP, expressing green fluorescent protein, were used for rapid screening of the transduction efficiency of virus in a variety of formulations due to the ease by which their transgene products could be visualized and quantitated. Formulations were prepared at five times the working concentration, sterilized by filtration and diluted with freshly purified virus in KPBS (pH 7.4) prior to use. Two hundred microliters of formulation containing virus (MOI 100) in the absence or presence of anti-adenovirus antibodies was added to differentiated Calu-3 cells seeded at a density of 1.25 × 105 cells/well in 12 well plates. Formulations remained in contact with cell monolayers for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release into the formulation with a standard cytotoxicity kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complete lysis was achieved by adding 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate to cells not exposed to formulations (positive control). Transduction efficiency was measured 48 h later either by histochemical staining and quantitation of cells expressing beta-galactosidase by visual inspection or by flow cytometry to quantitate cells expressing GFP.

Animal Studies

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at The University of Texas at Austin and the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston and are in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health for the humane treatment of animals. Two different strains of mice were used in these studies. Male B10.Br mice (MHC H-2k) were used to characterize the immune response to Ebola glycoprotein after immunization with the Ad-CAGoptZGP vector as described previously.13,14,24 Because this strain is difficult to breed,25,26 and is often not readily available in quantities sufficient from the supplier to perform the studies outlined in this manuscript, male C57/BL6 (MHC H-2d) mice were used for initial screening of formulations that improved transgene expression in vitro with minimal cytotoxic effects. Both strains were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (age 4–6 weeks, Bar Harbor, ME).

Nasal Administration of Virus/Immunization

Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled, 12 h light-cycled facility at the Animal Research Center of The University of Texas at Austin with free access to standard rodent chow (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) and tap water. Animals were anesthetized by a single intraperitoneal injection of a 3.9:1 mixture of ketamine (100 mg/mL) and xylazine (100 mg/mL). Once deep plane anesthesia was achieved, animals were placed on their stomach. The sedated animal’s head was rested upon an empty tuberculin syringe to keep the head in an upright position and to minimize choking or accidental swallowing of vaccine (as illustrated in Table of Contents graphic). Each mouse received a dose of 1 × 108 infectious particles of unformulated or formulated vaccine by direct application in the nasal cavity. The inhalation pressure from the animal’s natural breathing was sufficient to allow small droplets from a standard micropipette (Gilson, Middleton, WI) to gently enter the nasal cavity without the need to forcefully inject the solution. The right nostril received 10 μL and was allowed to dry for up to 5 min before adding an additional 10 μL to the left nostril, for a total volume of 20 μL per animal. The animal was observed in the relaxed position for an additional 10 min to guarantee comfortable breathing and ensure that the vaccine was not lost via sneezing (a rare occurrence that can result from touching the animal’s nose with the micropipette tip instead of allowing the tiny droplet to be gently pulled into the nose through natural inhalation pressure).

Establishment of Pre-Existing Immunity to Adenovirus

A first generation adenovirus that that does not contain a transgene cassette (AdNull) was used to establish pre-existing immunity to adenovirus serotype 5.27 Twenty-eight days prior to vaccination, mucosal PEI was induced by placing 5 × 1010 particles of AdNull in the nasal cavity as described above under the immunization protocol. Twenty-four days later, blood was collected via the saphenous vein and serum screened for anti-Ad neutralizing antibodies (NABs) as described below. At the time of vaccination, animals had an average anti-Ad circulating NAB titer of 315 ± 112 reciprocal dilution, which falls within the range of average values reported in humans after natural infection.28

Challenge with Mouse-Adapted Ebola Virus

Challenge experiments were performed under biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) conditions in an AAALAC accredited animal facility at the Robert E. Shope BSL-4 Laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. Twenty-one days postimmunization, vaccinated mice were transported to the BSL-4 lab, where they were challenged on day 28 by intraperitoneal injection with 1,000 pfu of mouse-adapted (30,000 × LD50) Ebola.29 After challenge, animals were monitored for clinical signs of disease and weighed daily for 14 days. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were determined using AST/SGOT and ALT/SGPT DT slides on a Vitros DTSC autoanalyzer (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY).

ELISPOT

ELISpot assays were performed using the ELISpot Mouse Set (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the spleen and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid as described previously,14 washed twice with complete DMEM, and added to wells of a 96 well ELISpot plate (5 × 105 cells/well) with the TELRTFSI peptide (0.5 μg/well) that carries the Ebola virus glycoprotein immunodominant MHC class I epitope for mice with the H-2k haplotype (B10.Br).30 Negative control cells were stimulated with an irrelevant peptide, which carries a binding sequence for influenza hemagglutinin (YPYDVPDYA, 0.5 μg/well). Spots were counted using an automated ELISpot reader (CTL-ImmunoSpot S5Micro Analyzer, Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights, OH).

Multiparameter Flow Cytometry

Splenocytes (2 × 106) isolated from immunized mice were cultured with TELRTFSI peptide (0.5 μg/well) and 1 μg/mL brefeldin A for 5 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Negative control cells were incubated with the YPYDVPDYA peptide (0.5 μg/well). Following stimulation, cells were surface stained with anti-mouse CD8α antibodies (1:150 in DPBS) and followed by intracellular staining with anti-mouse IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 antibodies as described.14 Positive cells were counted using four-color flow cytometry (FACS Fortessa, BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA). Over 500,000 events were captured per sample. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

CFSE Assay

Splenocytes were isolated 42 days postvaccination, stained using the Vybrant CFDA SE Cell Tracer kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in 96 well plates, and cultured for 5 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in the presence of the TELRTFSI or YPYDVPDYA peptides (0.5 μg/well) as described previously.24 Cells were incubated with a cocktail of antibodies (perCPCy5.5 labeled-anti-mouse-CD8, PE labeled-anti-mouse-CD44, and allophycocyanin (APC) labeled-anti-mouse-CD62L, 1:150) and analyzed by flow cytometry with over 1,000,000 events captured per sample.

Characterization of Ebola Glycoprotein-Specific Antibodies

Flat bottom, Immulon 2HB plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were coated with purified Ebola virus GP33-637ΔTM-HA (3 μg/well) in PBS (pH 7.4) overnight at 4 °C.31 Heat-inactivated serum samples were diluted (1:20) in PBS. One hundred microliters of each dilution was added to antigen-coated plates for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed 4 times and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgM (1:2,000, Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) antibodies in separate wells for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were washed, and substrate solution was added to each well. Optical densities were read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Tecan USA, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Adenovirus Neutralizing Assay

Heat-inactivated serum was diluted in 2-fold increments starting from a 1:20 dilution. Each dilution was incubated with AdlacZ (1 × 106 pfu) for 1 h at 37 °C and applied to HeLa cells (ATCC# CCL-2) seeded in 96 well plates (1 × 104 cells/well). After this time, 100 μL of DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS was added to each well. Twenty-four hours later, beta-galactosidase expression was measured by histochemical staining. Dilutions that reduced transgene expression by 50% were calculated using the method of Reed and Muench.32 The absence of neutralization in samples containing medium only (negative control) and FBS (serum control) and an average titer of 1:1,280 ± 210 read from an internal positive control stock serum were the criteria for qualification of each assay.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using SigmaStat (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) by performing a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between control and experimental groups, followed by a Bonferoni/Dunn post hoc test when appropriate. Differences in the raw values among treatment groups were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

One of the primary objectives of our laboratory is to develop a needle-free adenovirus based vaccine against Ebola. To achieve this goal, a variety of novel formulations were identified, prepared, and evaluated for their ability to maintain or improve transduction efficiency of the adenovirus with minimal cytotoxicity in Calu-3 cells, an in vitro model of the human respiratory epithelium.23 Over 400 formulations were assessed using a recombinant adenovirus expressing E. coli beta-galactosidase that differed from our vaccine construct only by the transgene cassette. This virus was chosen for these studies because it was available in sufficient quantity to support our high-throughput screening approach and for the ease by which the beta-galactosidase transgene product could be visualized and quantitated in vitro and in vivo. Data summarized here illustrate our heuristic approach where the number of formulation candidates tested in vitro is significantly reduced prior to the first in vivo screen for transduction efficiency and safety and further reduced to a select few for characterization of the immune response and subsequent evaluation of protection from lethal exposure to rodent-adapted Ebola.

In Vitro Characterization of Formulated Adenovirus Preparations

While many of the formulations included in the initial screen could maintain the stability of the adenovirus at ambient temperatures (data not shown), very few improved the in vitro transduction efficiency of the virus above that seen from virus formulated in saline. However, a preparation of 5% w/v sucrose increased transduction efficiency by a factor of 1.96 with respect to virus formulated in saline (pH 7.4, Figure 1A). Pluronic F68 (0.005% w/v), mannitol (1.25% w/v), and melezitose (1.25% w/v) alone each increased transduction by a factor of 1.78, 1.61, and 1.51, respectively. Formulations consisting of either raffinose or sorbitol alone at a 1.25% (w/v) concentration did not significantly enhance transduction (p = 0.06). A multicomponent formulation, F3, consisting of sucrose (10 mg/mL), mannitol (40 mg/mL), and 1% v/v poly(ethylene) glycol 3,000, previously found to stabilize the virus at ambient temperatures for extended periods of time,33 increased transduction 5-fold (p = 0.03). A formulation of 100 μM nDMPS was the second most efficacious formulation, however, significant cytoxicity (>80% cell lysis) was observed in cultures treated with this formulation. Less than 1% lysis was observed in cells treated with F3, making it sutiable for further evaluation in vivo (data not shown).

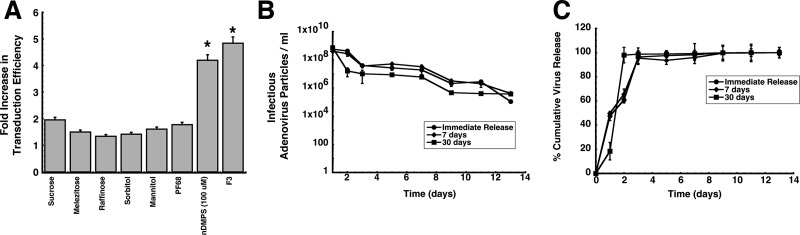

Figure 1.

Multicomponent formulations improve adenovirus transduction efficiency and stabilize virus in PLGA microspheres. (A) Transduction efficiency of excipients and formulations in differentiated Calu-3 cells. Cell monolayers were exposed to formulations containing a model recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vector expressing beta-galactosidase (AdlacZ) for 2 h at 37 °C. Transduction efficiency was determined by comparison of the number of cells expressing the beta-galactosidase transgene after treatment with formulated virus to the number of beta-galactosidase positive cells after treatment with virus in saline. Results are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean of data generated from triplicate samples over three separate experiments (n = 9 each formulation). PF68, Pluronic F68; nDMPS, N-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside; F3, formulation containing sucrose (10 mg/mL), mannitol (40 mg/mL), and 1% (v/v) poly(ethylene) glycol 3,000. * indicates a significant difference with respect to unformulated virus. (B) Adenovirus concentration versus time profiles of supernatants collected from PLGA microspheres stored at 37 °C. Ten milligrams of microspheres containing AdlacZ was suspended in 0.5 mL of sterile saline immediately after preparation (Immediate Release) or after storage at room temperature (25 °C) for 7 or 30 days. The number of infectious particles released at each time point was determined by serial dilution of collected supernatants and subsequent infection of Calu-3 cells. (C) In vitro release profiles of adenovirus from PLGA microspheres stored at room temperature over time. Release rates for freshly prepared beads did not significantly differ from those of beads stored at 25 °C for 7 days. The release rate increased 3-fold after storage for one month under the same conditions. Results depicted in panels B and C are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean of data generated from triplicate samples collected from six separate experiments.

In an effort to improve transduction efficiency in the presence of anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibodies, a method for encapsulation of adenovirus with the biocompatible polymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) was also developed.34 Only preparations that were capable of releasing active virus at concentrations relevant for immunization after storage at ambient temperatures would be considered for further in vivo testing. Approximately 10 ± 0.43% of the virus particles embedded in the polymer matrix were rendered uninfectious during processing, leaving the average virus concentration to be 1.08 ± 0.5 × 109 infectious virus particles (ivp) per milligram of microspheres. Infectious virus particles were released for 14 days, after which virus could no longer be detected (Figure 1B). Approximately 50% of the total amount of infectious virus embedded in freshly made polymer beads and in beads stored at 25 °C for 7 days was released within 24 h (Figure 1C). Storage of the beads at room temperature for 7 days did not significantly impact release rate as 1.34 × 108 ivp were released per day from freshly prepared beads and 1.76 × 108 ivp released per day after this time. Storage at room temperature for one month increased the rate of release to 3.5 × 108 ivp/day and promoted release of the entire dose (97.95%) within 48 h (Figure 1C).

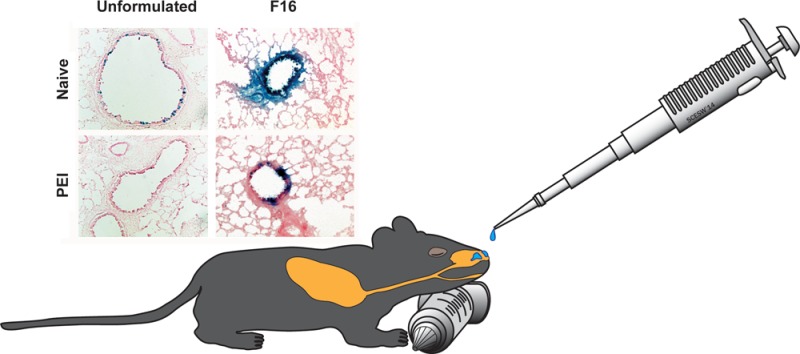

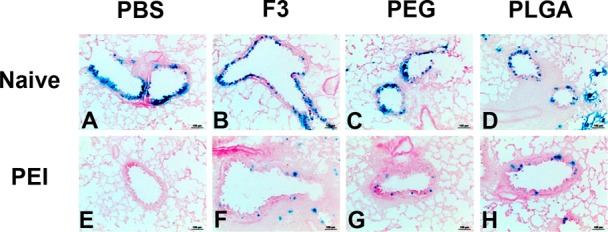

In Vivo Transduction Efficiency of Formulated Adenovirus Preparations in Naive Mice and Those with Pre-Existing Immunity

Based upon their ability to improve transduction efficiency and maintain virus stability, the F3 formulation and PLGA microspheres were selected for further evaluation of their effect on the transduction efficiency of adenovirus in naive mice and those with pre-existing immunity (PEI) to adenovirus. PEGylated virus was also selected for evaluation as a vaccine platform since we have previously shown that covalent attachment of poly(ethylene) glycol to the virus capsid improves the transduction efficiency in animals that have been exposed to adenovirus.35 Intranasal administration of AdlacZ, the model virus used for in vitro screening studies summarized in Figure 1, in each respective formulation resulted in high levels of transgene expression in epithelial cells of the conducting airways of naive mice 4 days after treatment (Figure 2, panels A–D). More importantly, each formulation significantly improved transgene expression in mice with pre-existing immunity to adenovirus (Figure 2, panels F–H) with respect to unformulated virus (Figure 2, panel E).

Figure 2.

Formulations improve adenovirus transduction efficiency in the lungs of naive mice and those with prior exposure to adenovirus. Naive C57BL/6 mice were given 5 × 1010 particles of the model recombinant virus used for in vitro screening of formulations (AdlacZ) suspended in potassium phosphate buffered saline (panel A), in formulation F3 (panel B), PEGylated virus (panel C), or 4.6 mg of PLGA microspheres containing the same dose of virus (panel D) by the intranasal route. A second set of mice were divided into the same treatment groups 28 days after receiving a dose of 5 × 1010 particles of AdNull, an E1/E3 deleted recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 virus similar to the AdlacZ vector which does not contain a transgene cassette (panels E–H). Mice in each group were sacrificed 4 days after administration of the AdlacZ vector. Images display representative gene expression patterns for 6 mice per treatment group. Magnification in each panel: 200×.

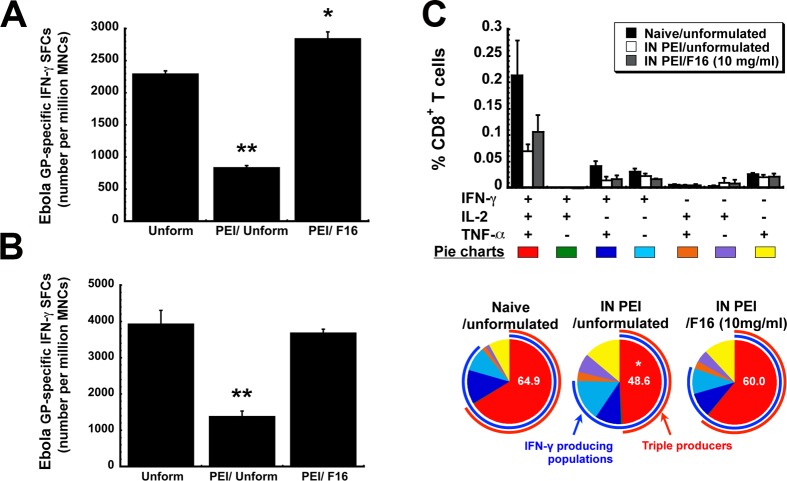

The T Cell Response: Magnitude

Since the transduction efficiency data in mice with pre-existing immunity to adenovirus looked promising for each formulation, the immune response elicited by each formulation was evaluated in B10.Br mice with the Ad-CAGoptZGP vector as described previously.13,14,24 The systemic antigen-specific T cell response generated by each formulation candidate was evaluated by quantitation of IFN-γ secreting mononuclear cells (MNCs) in the spleen by ELISpot. There was no significant difference in the amount of antigen-specific cells present in samples obtained from naive animals immunized with PEGylated, PLGA encapsulated, or unformulated virus (p > 0.05, Figure 3A). Samples from mice immunized with the F3 formulation contained slightly more antigen-specific cells than those from mice given unformulated vaccine (486.7 ± 4.8 spot-forming cells (SFCs)/million MNCs, F3, vs 414.7 ± 27.6 SFCs/million MNCs, unformulated). In contrast to what was observed in naive animals, PEI significantly decreased the number of activated IFN-γ secreting MNCs in the spleens of animals given each preparation except in those given the PEGylated vaccine (317.3 ± 58.2 spot-forming cells (SFCs)/million mononuclear cells (MNCs), naive, vs 234.7 ± 54.3 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI, Figure 3A). The most significant reduction in IFN-γ secreting MNCs was observed in animals given the microsphere preparation (426.7 ± 33.8 SFCs/million MNCs, naive, vs 57.3 ± 7.1 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI). Pre-existing immunity also significantly reduced the number of IFN-γ secreting cells recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in mice given unformulated vaccine (1,513.3 ± 63.6 SFCs/million MNCs, naive, vs 526.7 ± 98.2 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI, p < 0.01, Figure 3B). This response was not compromised in animals given the PEGylated and PLGA encapsulated vaccines (PEG, 2,666.7 ± 54.6 SFCs/million MNCs, naive, vs 580 ± 61.1 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI; PLGA, 1,280 ± 90.2 SFCs/million MNCs, naive, vs 1,360 ± 231.8 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI).

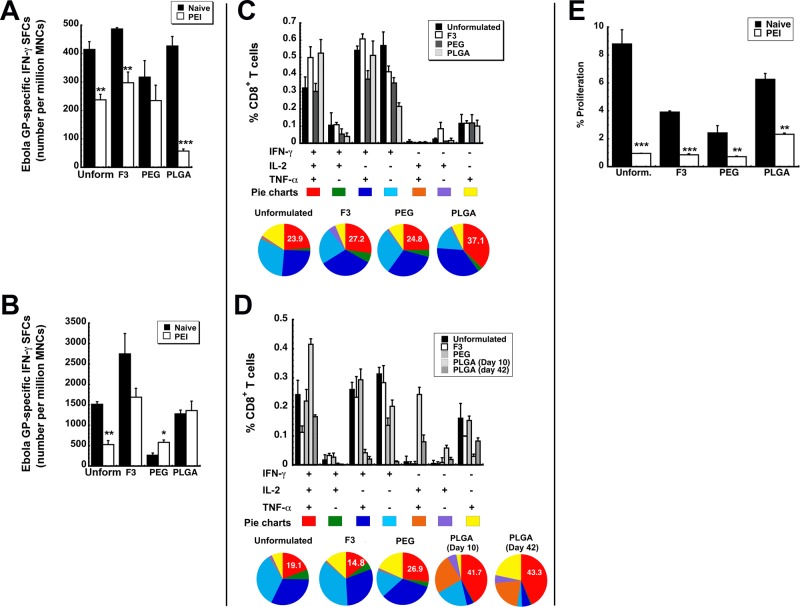

Figure 3.

Formulated preparations maintain antigen specific polyfunctional T cell responses in naive mice and those with prior exposure to adenovirus. Characterization of the immune response to Ebola glycoprotein was performed in B10.Br mice as described previously.12−14,24 (A) Magnitude of the systemic CD8+ T cell response against Ebola glycoprotein. The number of IFN-γ secreting mononuclear cells was quantitated in isolates taken 10 days after immunization from the spleen of naive B10.Br mice and those with prior-exposure to adenovirus by ELISpot. (B) Magnitude of the mucosal CD8+ T cell response against Ebola glycoprotein. The number of IFN-γ secreting mononuclear cells was quantitated 10 days after immunization in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of naive mice and those with prior-exposure to adenovirus by ELISpot. (C) Polyfunctionality of the Ebola glycoprotein-specific T cell response in naive mice. Ten days after immunization, splenocytes from 5 mice per treatment group were pooled and stimulated with an Ebola glycoprotein-specific peptide. Bar graphs illustrate the percentage of CD8+ tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-, interleukin 2 (IL-2)-, and interferon γ (IFN-γ)-producing cells detected after 5 h of antigen stimulation. Distribution of single-, double-, and triple-cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells is shown as various colors in pie chart diagrams. The relative frequency of cells that produce all three cytokines defines the quality of the vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell response. The proportion of these cells (IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+) generated in response to each treatment is written in the red section of each pie chart while the proportion of cells producing a single cytokine are represented by the light blue, purple, and yellow sections of each pie chart. (D) Polyfunctionality of the Ebola glycoprotein-specific T cell response in mice with prior exposure to adenovirus. Pre-existing immunity to adenovirus 5 was induced by instilling 5 × 1010 virus particles of AdNull, an E1/E3 deleted virus that does not contain a transgene cassette, in the nasal cavity of mice 28 days prior to immunization. Ten days after immunization, splenocytes were harvested and pooled as described in panel C. An increase in the number of polyfunctional cells, as indicated by an increase in the size of the red section of each pie graph, was fostered by several of the test formulations with respect to that produced by unformulated vaccine. (E) Quantitative analysis of the effector memory T cell response. Splenocytes were harvested 42 days after immunization, stained with CFSE, and stimulated with the TELRTFSI peptide for 5 days. Cells positive for CD8+, CD44HI, and CD62LLOW markers were then evaluated for CFSE by four-color flow cytometry. Data represent the average values obtained from three separate experiments each containing 5 mice per treatment. Error bars reflect the standard error of the data. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis.

The T Cell Response: Quality

Both the quantity and quality of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells induced by a vaccine platform significantly contribute to protection from a variety of infectious diseases such as AIDS, malaria, and hepatitis C.36 In animal models of infection, the quality of the antigen-specific T cell response can be assessed by stimulation of splenocytes, intracellular staining, and multiparameter flow cytometry to characterize the diversity of CD8+ T cell populations induced after immunization.37 The presence of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells, capable of producing several cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α) in response to the antigen, has been found to correlate with a reduction in circulating antigen and viral load since they are known to be the most responsive cells early in the infection process.38 Thus, strategies to increase the presence of cells capable of producing variety of cytokines and chemokines in response to a pathogen are part of many immunization strategies.39,40 In this context, functional analysis of cytokine producing CD8+ T cells at the single-cell level was performed to determine the ability of our formulations to improve the quality of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response. As part of this analysis, we were able to delineate seven distinct cytokine-producing cell populations based upon IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α secretion patterns.

As stated above, the relative frequency of cells that produce all three cytokines defines the quality of the vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell response. In naive mice, each formulation increased the number of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells, with the PLGA encapsulated vaccine producing the highest amount of these cells (IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+, 37.1 ± 5.04%, Figure 3C). Prior exposure to adenovirus in the nasal mucosa reduced the quality of the response generated by the unformulated vaccine (23.9 ± 3.24%, naive, vs 19.1 ± 6.76%, PEI) and F3 (27.2 ± 4.60%, naive, vs 14.8 ± 2.85%, PEI) while the response induced by the PEGylated vaccine was not compromised (24.8 ± 3.69%, naive, vs 26.9 ± 4.74%, PEI, Figure 3D). The polyfunctional response was somewhat strengthened in mice with prior exposure to adenovirus given the PLGA microspheres (37.1 ± 5.04%, naive, vs 41.7 ± 7.88%, PEI). This effect was also seen 42 days after immunization.

The T Cell Response: Memory

Antigen-specific CD8+ memory T cells are crucial components of long-term protection against viral infections. In order to predict the long-term efficacy of our formulated vaccines, we evaluated the effector memory CD8+ T cell response with a CFSE proliferation assay. Forty-two days after immunization, splenocytes isolated from naive mice given the unformulated vaccine contained 8.8 ± 1.02% effector memory CD8+ T cells capable of proliferating in response to an Ebola virus glycoprotein-specific MHC I-restricted peptide (Figure 3E). The number of effector memory CD8+ T cells was lower in samples harvested from animals immunized with the other formulations. Prior exposure to adenovirus significantly reduced the memory response in mice given the F3 formulation, PEGylated vaccine, and unformulated vaccine. The response elicited by PLGA encapsulated vaccine was suppressed by pre-existing immunity to a lesser degree than that observed in the other treatment groups (2.32 ± 0.09% vs 0.85 ± 0.08, F3, vs 0.72 ± 0.04, PEG).

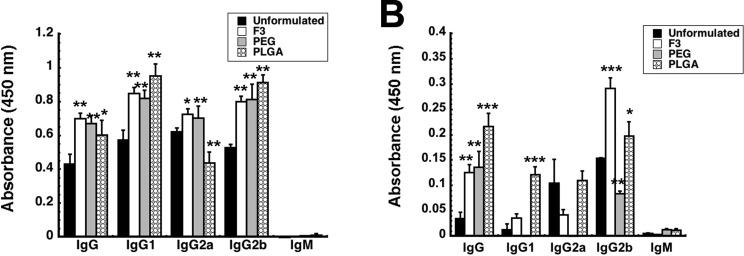

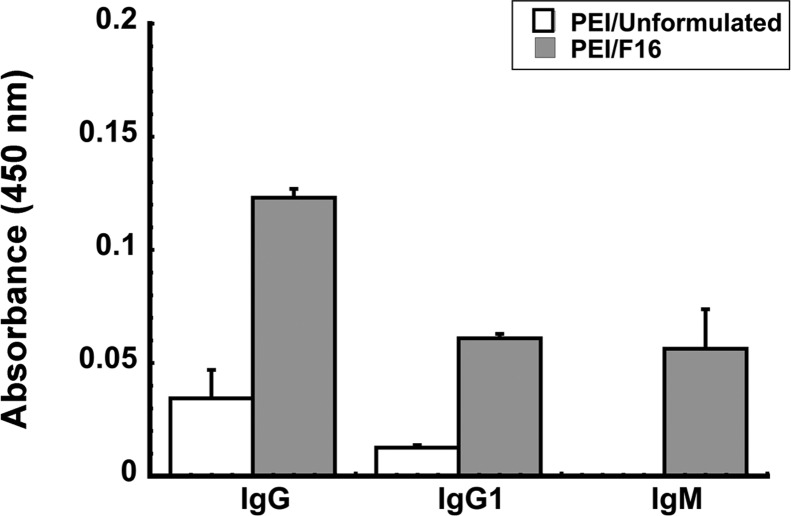

The Anti-Ebola Virus Antibody Response

We have previously found that prior exposure to adenovirus significantly reduced antibody-mediated immune response to Ebola glycoprotein in mice and guinea pigs.14 More specifically, we also found that a reduction in glycoprotein-specific IgG1 antibodies correlated with poor survival after challenge with rodent-adapted Ebola. Thus, we evaluated total anti-Ebola glycoprotein-specific immunoglobulin (IgG) and IgG isotypes in serum to determine if each formulation could counterbalance the effect of prior mucosal exposure to adenovirus on B cell mediated immune responses (Figure 4). Each formulation significantly increased the amount of each antibody isotype specific for Ebola glycoprotein (GP) in naive mice (Figure 4A). The IgG2a level in mice given PLGA microspheres was the only deviation from this trend as it was reduced by 29.9% with respect to unformulated virus (Figure 4A). Prior exposure to adenovirus significantly reduced each anti-Ebola GP-specific IgG isotype evaluated (Figure 4B). Although IgG2b levels in samples collected from mice immunized with the F3 formulation doubled, IgG1 and IgG2a levels were not significantly different from those seen in animals given unformulated virus. IgG1 and IgG2b levels in mice immunized with PLGA microspheres were 9.5 and 1.3 times those found in samples from mice given unformulated vaccine (Figure 4B). PEI to adenovirus reduced IgG2b levels by 45.9% in mice given PEGylated vaccine. IgG1 and IgG2a could not be detected in serum of mice immunized with this preparation. Trace levels of Ebola GP-specific IgM antibodies were found in serum from mice given the PLGA and PEGylated preparations.

Figure 4.

Formulated vaccines improve the anti-Ebola glycoprotein antibody response. Serum collected from individual mice 42 days after immunization was screened for total IgG and IgG isotypes by ELISA. (A) Antibody profile for naive mice. Naive B10.Br mice were given 1 × 108 particles of Ad-CAGoptZGP suspended in formulation or 4.6 mg of PLGA microspheres containing the virus in KPBS by the intranasal route. (B) Antibody profile for mice with pre-existing immunity to adenovirus. Pre-existing immunity was established by instillation of a dose of 5 × 1010 particles of AdNull in the nasal passages of B10.Br mice 28 days prior to immunization with formulated vaccines. In both panels, the average optical density read from samples obtained from each treatment group are presented to serve as a measure of relative antibody concentration and data reported as average values ± the standard error of the mean obtained from three separate experiments each containing 5 mice per treatment. In each panel, the asterisk indicates a significant difference with respect to naive, immunized animals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis.

Survival From Lethal Challenge

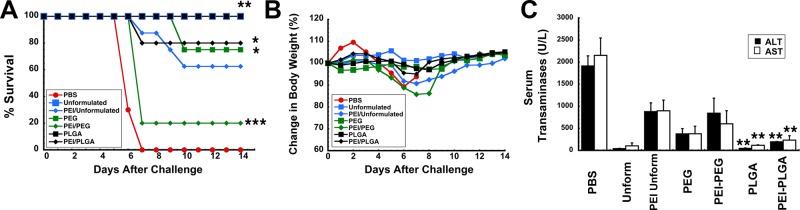

A marked reduction in the quality of the T cell response and in Th2 type antibody responses were found to be indicative of poor protection against lethal infection with Ebola virus in animals with PEI to adenovirus.14 Using this criteria, we decided that mice immunized with vaccine in formulation F3 would not be subject to challenge with a lethal dose of a mouse-adapted variant of Ebola (MA-EBOV) since neither facet of the immune response was notably improved by the formulation in mice with PEI to adenovirus. All of the naive mice given unformulated vaccine and the PLGA microsphere preparation survived lethal challenge with MA-EBOV (1,000 pfu ≃ 30,000 × LD50, Figure 5A). Twenty-five percent of naive mice given the PEGylated vaccine succumbed to infection. Sixty percent of the animals with PEI to adenovirus that were immunized with unformulated vaccine survived challenge. Eighty percent of mice with prior exposure to adenovirus that were immunized with the PEGylated preparation did not survive challenge. This group also demonstrated the most notable drop in body weight during the course of infection (Figure 5B). Samples taken from this group also revealed sharp elevations in ALT (842 ± 342 U/L) and AST (602 ± 298 U/L), indicative of severe liver damage from infection (Figure 5C). The PLGA microsphere preparation protected 80% of the mice with PEI to adenovirus from challenge. Serum ALT (195 ± 7.25 U/L) and AST (232 ± 10.1 U/L) levels were significantly lower in this treatment group with respect to those from animals given only saline (ALT, 1,913.6 ± 228.6 U/L; AST, 2,152 ± 394.77 U/L) for which the challenge was uniformly lethal and from mice with PEI given unformulated vaccine (ALT, 879 ± 197 U/L; AST, 898 ± 241 U/L, p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Formulations that augment both the polyfunctional T cell response and antigen-specific IgG1 antibody levels in mice with prior exposure to adenovirus improve survival from lethal challenge. Naive B10.Br mice were given 1 × 108 particles of Ad-CAGoptZGP suspended in formulation or 4.6 mg of PLGA microspheres containing the virus in KPBS by the intranasal route. Pre-existing immunity (PEI) was established by instillation of a dose of 5 × 1010 particles of AdNull in the nasal passages of B10.Br mice 28 days prior to immunization. Twenty-eight days after immunization, mice (n = 10/group) were challenged with a lethal dose of 1,000 pfu mouse-adapted Ebola (30,000 × LD50) by intraperitoneal injection. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curve. * indicates a significant difference with respect to the PEI/unformulated treatment group. (B) Body weight profile after challenge. No significant changes in body weight were noted in animals that survived challenge. The most significant drop in weight (∼15% reduction) was observed in animals with prior exposure to adenovirus immunized with the PEGylated preparation. (C) Serum alanine (ALT) and aspartate (AST) aminotransferase levels postchallenge. Samples from nonsurvivors were taken at time of death. Samples from survivors were taken 14 days postchallenge. In all panels, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis.

An In Vitro Assay for Quantitative Evaluation of Transduction Efficiency of Formulated Virus in the Presence of Neutralizing Antibodies

Because the PLGA and PEGylated preparations did not fully protect mice with PEI to adenovirus from lethal challenge, a secondary effort to identify formulations to improve survival was initiated. Based upon our initial results with the maltoside, nDMPS, we sought to identify compounds with similar properties but reduced toxicity profiles for further testing. Evaluation of transduction efficiency in the presence of neutralizing antibody was also included as a more stringent test to predict in vivo performance of formulation candidates. Three different amphiphols, differing only in the length of carbon chain in the hydrophobic region of the molecule, were first evaluated for their ability to preserve the transduction efficiency of the model AdlacZ vector in Calu-3 cells in the presence of neutralizing antibodies. Transduction efficiency of the virus in a formulation of 10 mg/mL of poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-decene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (referred to as F8) was reduced from 2.58 ± 0.03 × 107 to 1.94 ± 0.14 × 107 ivp/mL when the anti-adenovirus 5 antibody concentration in the infection media increased from 0.5 ND50 to 5 ND50 (Figure 6A). Virus formulated with 10 mg/mL poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-tetradecene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (F12) experienced the most significant drop in transduction efficiency when antibody concentration was increased from 0.5 ND50 to 5 ND50 (74% reduction, 1.64 ± 0.18 × 107 (0.5 ND50), to 4.28 ± 0.48 × 106 (5 ND50) lfu/mL). Transduction efficiency of the virus formulated with 10 mg/mL poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) substituted with 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine (F16) in the presence of 5 ND50 neutralizing antibody was not significantly different from that in the presence of the 0.5 ND50 concentration (p = 0.08, Figure 6A). This compound also had a very favorable toxicity profile as formulations of 1 and 10 mg/mL were cytotoxic to only 1.9 ± 0.47 and 1.8 ± 0.61% of the Calu-3 cell population respectively (Figure 6B). Increasing the concentration to five times that of the effective concentration (50 mg/mL) was still well tolerated by the Calu-3 cell monolayer with 3.63 ± 0.35% lysis noted.

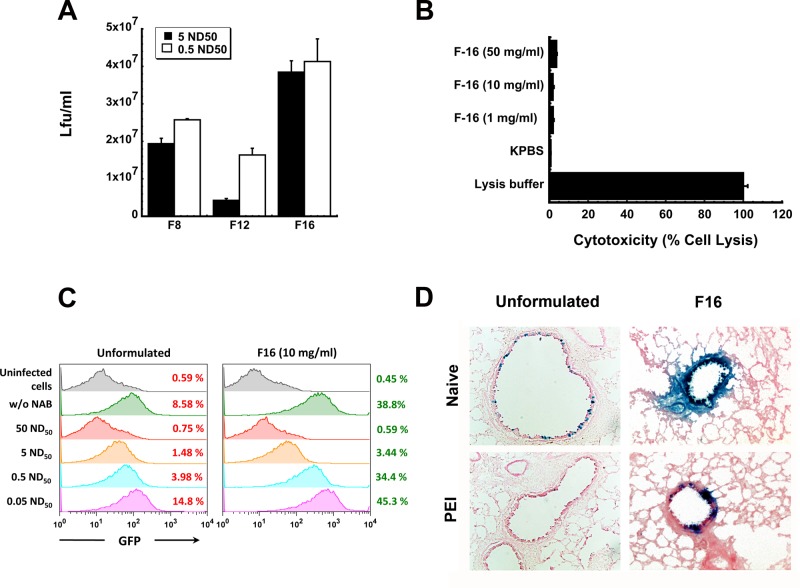

Figure 6.

Poly(maleic anhydrides): amphiphilic compounds that improve adenovirus transduction efficiency with minimal toxicity. A series of zwitterionic polymers of varying size were screened for their ability to improve the transduction efficiency of recombinant adenoviruses in lung epithelial cells. Initial screening of formulations in vitro and in vivo was performed with AdlacZ containing the beta-galactosidase transgene (panels A and D). Use of an E1/E3 deleted recombinant adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) and quantitation of infected cells by flow cytometry enhanced sensitivity of the screening assay so that subtle differences in transduction efficiency in the presence of anti-adenovirus neutralizing antibodies could be detected (panel C). (A) Transduction efficiency of formulated AdlacZ in the presence of neutralizing antibody. Formulations containing 1 × 108 infectious particles of AdlacZ were incubated with aliquots of a highly characterized neutralizing antibody stock for 1 h prior to infection of Calu-3 cells. Forty-eight hours later, beta-galactosidase positive cells were identified by histochemical staining. The number of infectious virus particles was tallied and calculated as described previously.18 (B) Toxicity profile of F16. Formulations were placed on differentiated Calu-3 cell monolayers for a period of 2 h. Culture medium was then assessed for LDH activity. Lysis buffer served as a positive control (100% lysis) and KPBS as a negative control. (C) Quantitative assessment of transduction efficiency of formulated AdGFP over a range of neutralizing antibody concentrations. In this experiment, 1 × 108 infectious particles of AdGFP were incubated in solution containing concentrations of anti-adenovirus antibody reflective of that found in the global population28,41 as described in panel A. Twenty-four hours after infection, infected cells, positive for GFP, were counted by flow cytometery. (D) Histological evaluation of transgene expression in the lung 4 days after intranasal administration of formulated virus. A single dose of 5 × 1010 infectious particles of AdlacZ was given to naive mice or mice with PEI to adenovirus induced by the intranasal route. Four days later, mice were sacrificed, and tissue was harvested and stained for transgene expression. Sections illustrate representative transgene expression patterns found in tissue collected from 6 animals per treatment. Magnification for unformulated panels: 200×. Magnification for F16 panels: 400×. Results in panels A–C are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean of data generated from triplicate samples collected from four separate experiments.

Before the vaccine formulated with the F16 preparation was tested in vivo, it underwent an additional round of screening to confirm that transduction efficiency was adequately improved in the presence of neutralizing antibody. In order to increase the sensitivity of this assay and make it a better predictor of in vivo performance, we decided to incorporate a model a recombinant adenovirus 5 vector expressing green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) into our test formulations and evaluate transduction efficiency by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). In order to generate data that was clinically relevant, the virus was incubated with five different solutions containing a series of neutralizing antibody concentrations spanning those found in the general population.28,41 Cells infected with the virus were quantitated by flow cytometry 48 h after infection. While 8.58% of the monolayer infected with unformulated virus expressed the transgene, the F16 formulation increased transduction efficiency to 38.8% (Figure 6C). This assay allowed us to see significant differences in transduction efficiency of the formulated virus in the presence of the 0.5 ND50 and 5 ND50 antibody concentrations that were not detected by the infectious titer assay (3.44%, 0.5 ND50, vs 34.4%, 5 ND50). Although the formulation improved transduction efficiency of the virus over a wide range of antibody concentrations, the limit of this improvement was reached at the 50 ND50 concentration, where the formulation could no longer protect the virus from neutralization.

Adenovirus formulated with the F16 compound was well tolerated in naive animals and those with PEI to adenovirus. Almost every epithelial cell in both large and small airways was transduced by virus formulated with F16 (Figure 6D). Highly concentrated areas of transgene expression were also found in small airways of mice with circulating neutralizing antibody levels of 262 ± 43 reciprocal dilution given virus in this formulation. In contrast, PEI to adenovirus prevented transgene expression in both large and small airways of mice given unformulated virus. Serum transaminases, standard indicators of adenovirus toxicity,42 in both naive animals and those with PEI to adenovirus immunized with the F16 formulation were reduced by 40% with respect to similar treatment groups given unformulated vaccine (data not shown).

The Immune Response Generated by Formulation F16 in Mice with Pre-Existing Immunity

Because prior formulation candidates did not fully confer protection in mice in which PEI was established through the nasal mucosa, evaluation of the F16 formulation in vivo focused solely on the ability of this formulation to improve the immune response to the encoded Ebola glycoprotein under these specific conditions. As seen in prior studies, PEI significantly compromised the production of GP-specific IFN-γ-secreting mononuclear cells isolated from spleen (Figure 7A) and BAL fluid (Figure 7B) in animals given unformulated vaccine (p < 0.01). PEI induced by the mucosal route also significantly reduced the frequency of GP-specific multifunctional CD8+ T cells elicited by the unformulated vaccine (naive, 64.9 ± 4.88%, vs IN PEI/unformulated, 48.6 ± 3.66%, p < 0.05; Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Formulation F16 improves quantitative and qualitative Ebola glycoprotein-specific CD8+ T cell responses in mice with prior exposure to adenovirus. PEI to adenovirus 5 was induced by instilling 5 × 1010 virus particles of AdNull, an E1/E3 deleted virus that does not contain a transgene cassette, in the nasal cavity of mice 28 days prior to immunization. (A) The systemic effector CD8+ T cell response. Ten days after vaccination, mononuclear cells from the spleen were harvested and stimulated with an Ebola GP-specific peptide and responsive cells were quantitated by ELISpot. (B) The mucosal effector CD8+ T cell response. Ten days after vaccination, mononuclear cells collected from BAL fluid were harvested, pooled according to treatment, and stimulated with an Ebola GP-specific peptide and responsive cells were quantitated by ELISpot. (C) The polyfunctional CD8+ T cell response. Ten days after immunization, splenocytes from 5 mice per treatment group were pooled and stimulated with an Ebola glycoprotein-specific peptide. Each positively responding cell was assigned to one of 7 possible combinations of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α production and quantitated as shown in the bar graph. The most potent responders, those producing all 3 cytokines in response to stimulation, are depicted by the red arcs in the pie charts. The proportion of cells in samples from each treatment group that produce IFN-γ is depicted by the blue arc. The number in each pie chart denotes the percentage of triple producers found in samples from a given treatment group. Data reflect average values ± the standard error of the mean for six mice per group. * indicates a significant difference with respect to the naive/unformulated group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis.

The F16 formulation improved the immune response in animals with PEI to adenovirus as the number of GP-specific, IFN-γ-secreting mononuclear cells isolated from the spleen of these animals was notably higher than that from naive animals given unformulated vaccine (2,290 ± 51 SFCs/million MNCs, naive, vs 2,840 ± 110 SFCs/million MNCs, PEI/F16, p < 0.05, Figure 7A). The number of antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting mononuclear cells isolated from the BAL fluid of animals given the F16 formulation was not statistically different from that found in naive animals given unformulated vaccine (p = 0.07, Figure 7B). This trend was also observed with respect to the multifunctional CD8+ T cell response as it also did not change with respect to that found in naive animals given unformulated vaccine (naive/unformulated, 64.9 ± 4.88%, vs IN PEI/F16 (10 mg/mL), 60.0 ± 9.1%, p = 0.055; Figure 7C). Forty-two days after immunization, the effector memory CD8+ T cell response was also evaluated in mice immunized with unformulated vaccine or the F16 preparation. The F16 formulation increased the memory response by a factor of 3.3 from 0.28 ± 0.15% (unformulated) to 0.93 ± 0.25% (F16, data not shown). Serum from animals with pre-existing immunity to adenovirus that were immunized with the F16 preparation contained 4 times more anti-Ebola glycoprotein antibodies than that from animals given unformulated vaccine (Figure 8). Samples from these animals also contained 5 times more of the IgG1 isotype and notable levels of antigen-specific IgM antibodies.

Figure 8.

Formulation F16 improves the antigen specific antibody response in mice with prior exposure to adenovirus. The average optical density read from individual samples obtained from each treatment group are presented to serve as a measure of relative antibody concentration and data reported as average values ± the standard error of the mean obtained from two separate experiments each containing 6 mice per treatment. The limit of detection for the assay is 0.01 absorbance unit. **p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis.

Discussion

Development of effective vaccines against Ebola is a difficult task due to the lethality of the virus, which makes testing of any vaccine on humans impossible. In addition, outbreaks remain quite unpredictable, making identification of a specific high-risk population to be targeted for a clinical efficacy trial problematic.43 Therefore, potential vaccine candidates must be evaluated in animal models of Ebola infection prior to clinical testing. Data from these models must provide a clear indication of measurable, predictive markers that strongly correlate with survival, which can then be evaluated in the absence of exposure in a clinical setting.44 To date, a single dose of several different vaccines derived from recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 that express the Ebola virus glycoprotein has been highly efficacious in naive animals.12,45,46 However, none of these platforms have been completely effective in animals with PEI to adenovirus.47−49

We have recently shown that immunization with an adenovirus 5-based Ebola vaccine by the same route in which pre-existing immunity is induced significantly diminishes the antigen-specific multifunctional CD8+ T cell response and antibody production and that both these parameters contribute the protective efficacy of the vaccine.14 Therefore, the primary objective of these studies was to develop novel formulations for a nasal vaccine against Ebola that would be effective in those with PEI to adenovirus by two distinct mechanisms: physical protection of the virus from neutralization by anti-adenovirus antibodies and enhancement of antigen expression from virus that escaped neutralization. Prior work in our laboratory identified formulations consisting of pharmaceutically acceptable excipients that enhanced the physical stability of the virus and increased transduction efficiency to the lung epithelium with minimal toxicity.33,50 One of these formulations, referred to in this manuscript as F3, significantly improved transduction efficiency of the virus in an in vitro model of the airway epithelium and in naive animals (Figures 1 and 2). However, this effect alone was not sufficient to fortify the antigen-specific immune response in mice exposed to adenovirus 5 28 days prior to immunization (Figures 3 and 4).

Nanoparticles made of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) copolymer blends have been evaluated and developed for controlled release of a variety of therapeutic drugs since the 1980s.51 While this delivery platform has been utilized in several licensed products to improve the bioavailability of hydrophobic drugs,52 it has yet to be successfully utilized in a vaccine product.53 However, improvements in manufacturing and sterilization processes for PLGA nanoparticles have allowed several vaccine candidates using this system to progress to phase I/II and II/III clinical testing.54 Particle size is one of the most influential characteristics of the potency of a vaccine preparation as it can dictate how antigens are processed.55 Recently, it was found that immunization with PLGA particles within the 200–600 nm size range stimulated strong Th1 responses with high levels of circulating IFN-γ while particles within the 2–8 μm range fostered IL-4 production and associated Th2 responses.56 This paradigm is supported by our studies as the average particle size of the encapsulated vaccine preparation fell within the 2–8 μm range and Th2 responses were predominant in naive animals and those with PEI to adenovirus (Figure 4). Surprisingly, the encapsulated vaccine was only partially protective in animals with PEI. This most likely is due to the significant reduction in the systemic CD8+ T cell response resulting from poor distribution of particles from the respiratory compartment. It is also important to realize that the local antigen-specific immune response was not compromised by PEI to adenovirus. Thus, full protection may have been observed if the immunized mice were exposed to the challenge virus via the respiratory tract. Additional studies to tailor the size and surface chemistry of the microparticles to facilitate uptake and processing by migrating antigen presenting cells are warranted.

PEGylation has been successfully used to reduce aggregation, improve solubility, and dampen the immunogenicity of a variety of licensed protein-based therapeutics.57 We developed a process for PEGylation of recombinant adenoviruses that improved transgene expression in several animal models of PEI.20,35 Although the immune response against the transgene was not evaluated in those studies, data summarized in this manuscript suggest that PEGylation significantly alters the immune response to an encoded transgene in naive animals and those with PEI to the virus by potentially different mechanisms. In naive animals, the PEGylated vector generated qualitative antigen-specific T cell responses that were similar to those generated by unmodified virus (Figure 3C). The antibody-mediated response was also not impacted by PEGylation (Figure 4). The quantitative T cell response, however, was reduced in these animals (Figure 3A). While the PEGylated vector improved the polyfunctional T cell response in mice with PEI to adenovirus (Figure 3C), IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies against the Ebola virus glycoprotein were not detected in serum collected from these animals (Figure 4B). Taken together, these findings suggest that PEG alters the manner by which the virus and the transgene product are processed by antigen presenting cells.58,59 They also suggest, especially in naive animals, that conjugation of PEG to the virus capsid delays processing of an encoded antigenic transgene. This has been observed by others who have found that priming and boosting doses of a PEGylated vector were necessary to induce antigen-specific T cell responses that were greater than that achieved by a single dose of the PEGylated vector or the unmodified virus alone.60

Immune responses correlating with protection from Ebola virus infection have long been the subject of fervid debate.61−63 Some reports suggest that the humoral arm of the adaptive immune response is required for protection,48,64,65 while others point to cell mediated immunity as the predominant protective mechanism.17,66 In the studies summarized here, we found that when specific IgG antibody subtypes were not produced against the Ebola glycoprotein in response to the PEGylated vaccine, survival was poor, with 20% of mice with PEI surviving challenge. This finding may be useful in refining strategies to utilize combinations of antibodies to treat Ebola infection.67 When antibody levels were high and the antigen-specific quantitative T cell response was suppressed, significant yet only partial protection from challenge was achieved in naive animals given the PEGylated preparation (75% survival) and in mice with PEI given the PLGA preparation (80% survival). Taken together, these results suggest that antigen-specific antibodies are critical for protection and that the T cell response supports protection if a certain level of neutralizing antibody is present. These observations are in line with prior observations in rodent models of infection14,63 and should be evaluated in larger models of Ebola hemorrhagic fever that are more reflective of the human disease.44

The immune response generated by the preparation delineated as F16 restored the antigen-specific multifunctional CD8+ T cell and antibody responses compromised by PEI to adenovirus serotype 5. The primary component in this formulation is an amphiphilic polymer with alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic side chains that was originally developed as an alternative to surfactants for stabilizing membrane proteins in aqueous solution and delivering biomolecules across lipid bilayers of the cell membrane.68,69 Unlike detergent-based micelles, this compound assumes a belt-like structure around the trans-membrane domain of proteins in the cell membrane. At neutral pH, the overall surface charge of the polymer is highly positive, allowing it to immobilize negatively charged biomolecules and promote interaction with the anionic cell surface.70 Since the adenovirus capsid bears a net negative charge at neutral pH,71 we believe that this compound enhances transduction efficiency of the virus in this manner. The observation that transduction efficiency of the virus in the presence of neutralizing antibody is directly influenced by the length of the hydrophobic region of the compound suggests that the F16 compound covered the virus in a manner that most effectively prevented antibody binding. Additional studies to characterize the interaction between this compound and the virus and how it impacts uptake and processing by antigen presenting cells are warranted. Evaluation of this compound in a primate challenge model has recently been described.72

Since many pathogens, much like Ebola, have mastered the art of outwitting host immune responses,73−75 vaccine candidates must elicit strong and broad immune responses that are long lasting and difficult for the pathogen to counteract. While advances in reverse vaccinology and proteomics have accelerated discovery and production of antigenic candidates that do not bear the safety concerns associated with live and attenuated organisms, they cannot, on their own, generate fully protective immune responses. Thus, identification of delivery systems that protect the antigen and direct it to specific components of the immune system and discovery of compounds that stimulate antigen-specific immune responses are critical to the development of any vaccine program. This is even more important for preparations that are to be delivered to the nasal mucosa since many of the known conventional adjuvants are either toxic or not active when given by the intranasal route.7,76 In the studies summarized here, we have identified a novel, nontoxic excipient with unique physicochemical properties that substantially augments the transduction efficiency and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5-based Ebola vaccine in the presence of pre-existing immunity to the adenovirus vector. Graded, stepwise evaluation of each formulation in vitro and in vivo allowed us to confirm that specific components of the immune response play a role in protection from Ebola. While some of these results may only apply specifically to the adenovirus vector and Ebola, they may be informative for improving other vaccine platforms based upon microbes also routinely encountered in the environment like Salmonella, vaccinia, herpes simplex, and human respiratory syncytial virus.77−80

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lihong Zhang, Terry Juelich, and Jennifer Smith of the UTMB BSL-4 facility for their help with Ebola challenge studies. We acknowledge technical assistance of Michael Boquet and Joe Dekker in early formulation development. We would also like to extend deep appreciation to Dr. Erica Ollmann Saphire and Marnie Fucso of The Scripps Research Institute for providing the Ebola GP33-637ΔTM-HA plasmid and assistance with glycoprotein purification. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health NIAID Grant U01AI078045 (M.A.C.).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): As Director of the Robert E. Shope BSL-4 Laboratory, A.N.F. has participated in the development of a variety of vaccines and therapeutics for Ebola virus disease including the vaccine described in this manuscript. J.H.C., S.C.S., and M.A.C. have no competing interests to declare.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Littman R. J. The Plauge of Athens: Epidemiology and Paleopathology. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2009, 765456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese P.; Schulze K.; Ebensen T.; Prochnow B.; Guzman C. A. Vaccine Adjuvants: Key Tools for Innovative Vaccine Design. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13202562–2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany I.; Rappuoli R.; De Gregorio E. Vaccines for the 21st Century. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 66708–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E.; Rappuoli R. From Empiricism to Rational Design: A Personal Perspective of the Evolution of Vaccine Development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 47505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejupesland P. G. Nasal Drug Delivery Devices: Characteristics and Performance in a Clinical Perspective—a Review. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2013, 3142–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna A.; Alves G.; Serralheiro A.; Sousa J.; Falcao A. Intranasal Delivery of Systemic-Acting Drugs: Small-Molecules and Biomacromolecules. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 8818–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese P.; Sakthivel P.; Trittel S.; Guzman C. A. Intranasal Formulations: Promising Strategy to Deliver Vaccines. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2014, 11101619–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren J.; Svennerholm A. M. Vaccines against Mucosal Infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012, 243343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter N. J.; Curran M. P. Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (Flumist®; FluenzTM): A Review of Its Use in the Prevention of Seasonal Influenza in Children and Adults. Drugs 2011, 71121591–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L. J.; Carter N. J.; Curran M. P. Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (FluenzTM): A Guide to Its Use in the Prevention of Seasonal Influenza in Children in the EU. Paediatr. Drugs 2012, 144271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhere R.; Yeolekar L.; Kulkarni P.; Menon R.; Vaidya V.; Ganguly M.; Tyagi P.; Barde P.; Jadhav S. A Pandemic Influenza Vaccine in India: From Strain to Sale within 12 Months. Vaccine 2011, 29Suppl. 1A16–A21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A.; Zhang Y.; Croyle M.; Tran K.; Gray M.; Strong J.; Feldmann H.; Wilson J. M.; Kobinger G. P. Mucosal Delivery of Adenovirus-Based Vaccine Protects against Ebola Virus Infection in Mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 96Suppl. 2S413–S420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle M. A.; Patel A.; Tran K. N.; Gray M.; Zhang Y.; Strong J. E.; Feldmann H.; Kobinger G. P. Nasal Delivery of an Adenovirus-Based Vaccine Bypasses Pre-Existing Immunity to the Vaccine Carrier and Improves the Immune Response in Mice. PLoS One 2008, 310e3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H.; Schafer S. C.; Zhang L.; Juelich T.; Freiberg A. N.; Croyle M. A. Modeling Pre-Existing Immunity to Adenovirus in Rodents: Immunological Requirements for Successful Development of a Recombinant Adenovirus Serotype 5-Based Ebola Vaccine. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 1093342–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood J. E.; Dezure A. D.; Stanley D. A.; Novik L.; Enama M. E.; Berkowitz N. M.; Hu Z.; Joshi G.; Ploquin A.; Sitar S.; Gordon I. J.; Plummer S. A.; Holman L. A.; Hendel C. S.; Yamshchikov G.; Roman F.; Nicosia A.; Colloca S.; Cortese R.; Bailer R. T.; Schwartz R. M.; Roederer M.; Mascola J. R.; Koup R. A.; Sullivan N. J.; Graham B. S.; VRC 207 Study Team . Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vector Ebola Vaccine—Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley D. A.; Honko A. N.; Asiedu C.; Trefry J. C.; Lau-Kilby A. W.; Johnson J. C.; Hensley L.; Ammendola V.; Abbate A.; Grazioli F.; Foulds K. E.; Cheng C.; Wang L.; Donaldson M. M.; Colloca S.; Folgori A.; Roederer M.; Nabel G. J.; Mascola J.; Nicosia A.; Cortese R.; Koup R. A.; Sullivan N. J. Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vaccine Generates Acute and Durable Protective Immunity against Ebolavirus Challenge. Nat. Med. 2014, 20101126–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan N. J.; Hensley L.; Asiedu C.; Geisbert T. W.; Stanley D.; Johnson J.; Honko A.; Olinger G.; Bailey M.; Geisbert J. B.; Reimann K. A.; Bao S.; Rao S.; Roederer M.; Jahrling P. B.; Koup R. A.; Nabel G. J. CD8+ Cellular Immunity Mediates rAd5 Vaccine Protection against Ebola Virus Infection of Nonhuman Primates. Nat. Med. 2011, 1791128–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan S. M.; Wonganan P.; Obenauer-Kutner L. J.; Sutjipto S.; Dekker J. D.; Croyle M. A. Controlled Inactivation of Recombinant Viruses with Vitamin B2. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 1481–2132–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle M. A.; Yu Q. C.; Wilson J. M. Development of a Rapid Method for the PEGylation of Adenoviruses with Enhanced Transduction and Improved Stability under Harsh Storage Conditions. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000, 11121713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonganan P.; Croyle M. A. PEGylated Adenoviruses: From Mice to Monkeys. Viruses 2010, 22468–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croyle M. A.; Le H. T.; Linse K. D.; Cerullo V.; Toietta G.; Beaudet A.; Pastore L. PEGylated Helper-Dependent Adenoviral Vectors: Highly Efficient Vectors with an Enhanced Safety Profile. Gene Ther. 2005, 127579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhier F.; Ansorena E.; Silva J. M.; Coco R.; Le Breton A.; Préat V. PLGA-Based Nanoparticles: An Overview of Biomedical Applications. J. Controlled Release 2012, 1612505–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong H. X.; Traini D.; Young P. M. Pharmaceutical Applications of the Calu-3 Lung Epithelia Cell Line. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2013, 1091287–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H.; Schafer S. C.; Zhang L.; Kobinger G. P.; Juelich T.; Freiberg A. N.; Croyle M. A. A Single Sublingual Dose of an Adenovirus-Based Vaccine Protects against Lethal Ebola Challenge in Mice and Guinea Pigs. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 91156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner S. P.; Anderson C. P.; Harrison D. E.; Walford R. L.; Finch C. E. Polygenic Influences on the Length of Oestrous Cycles in Inbred Mice Involve MHC Alleles. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 1992, 196361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning S. L.; Appel M. Y.; Berger S. A.; Korngold R.; Friedman T. M. The Immunological Impact of Genetic Drift in the B10.Br Congenic Inbred Mouse Strain. J. Immunol. 2009, 18374261–4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan S. M.; Boquet M. P.; Ming X.; Brunner L. J.; Croyle M. A. Impact of Transgene Expression on Drug Metabolism Following Systemic Adenoviral Vector Administration. J. Gene Med. 2006, 85566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch D. H.; Kik S. V.; Weverling G. J.; Dilan R.; King S. L.; Maxfield L. F.; Clark S.; Nganga D.; Brandariz K. L.; Abbink P.; Sinangil F.; De Bruyn G.; Gray G. E.; Roux S.; Bekker L. G.; Dilraj A.; Kibuuka H.; Robb M. L.; Michael N. L.; Anzala O.; Amornkul P. N.; Gilmour J.; Hural J.; Buchbinder S. P.; Seaman M. S.; Dolin R.; Baden L. R.; Carville A.; Mansfield K. G.; Pau M. G.; Goudsmit J. International Seroepidemiology of Adenovirus Serotypes 5, 26, 35, and 48 in Pediatric and Adult Populations. Vaccine 2011, 29325203–5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M.; Davis K.; Geisbert T.; Schmaljohn C.; Huggins J. A Mouse Model for Evaluation of Prophylaxis and Therapy of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179Suppl. 1S248–S258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M.; Matyas G. R.; Grieder F.; Anderson K.; Jahrling P. B.; Alving C. R. Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes to Ebola Zaire Virus Are Induced in Mice by Immunization with Liposomes Containing Lipid A. Vaccine 1999, 1723–242991–2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. E.; Fusco M. L.; Ollman-Saphire E. An Efficient Platform for Screening Expression and Crystallization of Glycoproteins Produced in Human Cells. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 44592–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L. J.; Muench H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty Percent Endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Renteria S. S.; Clemens C. C.; Croyle M. A. Development of a Nasal Adenovirus-Based Vaccine: Effect of Concentration and Formulation on Adenovirus Stability and Infectious Titer During Actuation from Two Delivery Devices. Vaccine 2010, 2892137–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H.; Croyle M. A. Development of Intranasal Formulations for a Human Adenovirus Serotype 5-Based Vaccine with Potential to Bypass Pre-Existing Immunity. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20Suppl. 1S176. [Google Scholar]

- Croyle M. A.; Chirmule N.; Zhang Y.; Wilson J. M. “Stealth” Adenoviruses Blunt Cell-Mediated and Humoral Immune Responses against the Virus and Allow for Significant Gene Expression Upon Readministration in the Lung. J. Virol. 2001, 75104792–4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser K. A.; Schenkel J. M.; Jameson S. C.; Vezys V.; Masopust D. Pre-Existing High Frequencies of Memory CD8+ T Cells Favor Rapid Memory Differentiation and Preservation of Proliferative Potential Upon Boosting. Immunity 2013, 391171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski C. E.; Corti D.; Mele F.; Pinto D.; Lanzavecchia A.; Sallusto F. Dissecting the Human Immunologic Memory for Pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 240140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seder R. A.; Darrah P. A.; Roederer M. T-Cell Quality in Memory and Protection: Implications for Vaccine Design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 84247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F.; Lanzavecchia A.; Araki K.; Ahmed R. From Vaccines to Memory and Back. Immunity 2010, 334451–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman R. L.; Sher A.; Seder R. A. Vaccine Adjuvants: Putting Innate Immunity to Work. Immunity 2010, 334492–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H.; Dekker J.; Schafer S. C.; John J.; Whitfill C. E.; Petty C. S.; Haddad E. E.; Croyle M. A. Optimized Adenovirus-Antibody Complexes Stimulate Strong Cellular and Humoral Immune Responses against an Encoded Antigen in Naive Mice and Those with Preexisting Immunity. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19184–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]