Abstract

Background:

Stillbirth is one of the deepest losses that can inflict a broad range of cognitive, mental, spiritual, and physical turmoil. Many researchers believe that the failure to provide the care required by health teams during the hard times is the main determinant of maternal mental health in the future. In other words, social support can significantly improve the mental health outcomes of mothers after stillbirth. This study aimed to explore social support to aid mothers in adaptation after the experience of stillbirth.

Materials and Methods:

This was a qualitative content analysis in which 15 women who had experienced stillbirth participated. They were selected through purposeful sampling method. Data were gathered by individual interviews recorded on audiotapes, transcribed, and analyzed. Interview transcriptions were coded and then classified. Finally, two main categories and five subcategories emerged.

Results:

Analysis of participants’ viewpoints and their statements about social support led to the emergence of the two main categories of support from relatives and support from social support systems with two and three subcategories, respectively. Analysis of findings showed that mothers experiencing stillbirth need the support of their spouse and family and friends through sympathizing, in performing everyday activities and to escape loneliness. These women require support from a peer group to exchange experiences and from trauma counseling centers to meet their needs.

Conclusions:

It seems necessary to revise and modify the care plan in the experience of stillbirth using these results and, of course, to be considered by a panel of experts in order to provide social support to these women. Thus, midwives and healthcare provider can act, based on the development and strengthening of social protection of women experiencing stillbirth, to provide these women with effective and appropriate care.

Keywords: Qualitative study, social, stillbirth, support

INTRODUCTION

Stillbirth is a tragedy for the birth parents because it breaks the emotional attachment that was created between them and their baby.[1] Childbirth, even when the outcome is the birth of a newborn, can cause much stress and depression in women. Stillbirth causes a significant increase in the incidence of both disorders and increases the risk of poor mental health outcomes during the postpartum period.[2] The terms “stillbirth” or “infant death” are used to describe the absence of signs of life at birth, after 22 weeks of gestation.[3] Fetal death at any age and from any cause is a traumatic experience for a life undergoing change.[4] Stillbirth is one of the deepest and most important losses in the lives of women and could be associated with a wide range of cognitive, emotional, spiritual, and physical impacts. Following stillbirth, most mothers look for answers and any explanation regarding their baby's death and they may unreasonably blame themselves.[5] Therefore, appropriate management of the grief of parents after stillbirth is essential and its impact can be observed in the reduction of anxiety and depression and good outcomes in subsequent pregnancies.[6]

At this critical time, support for the mothers to maintain their physical and mental health is essential. However, sometimes due to social pressure caused by encountering the children of the family, these grieving mothers are reluctant to communicate with others.[7] Moreover, the role of social support systems should not be overlooked.[8] In other words, these women feel that after experiencing stillbirth they need social support more than before, while generally their grief is considered trivial.[9] Comprehensive care for mothers and fathers after experiencing stillbirth should include counseling and psychological support.[10] Studies also suggest that support groups play an important role in providing practical assistance in relation to strategies for adapting, and reducing psychological distress and depressive symptoms in women.[11] This interpretation reflects the fact that if the happy nature of birth does not connect with the sadness of death in an appropriate way, perinatal bereavement will be intensified.[12] Cacciatore et al., in an investigation of the experience of care after fetal death in Swedish men, stated that most women who had suffered stillbirth were grateful of the healthcare providers who allowed them to see the baby and hold a mourning ceremony. In addition, healthcare providers who had supported the bereaved mothers had helped them in reducing the long-term negative psychological consequences.[13]

In this regard, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence of England recommended that to identify the specific characteristics of the parent and specific components of this support tailored to each community's culture, research should be done in that community.[14] It should be noted that despite imposing a large burden on women and their families, stillbirth remains largely overlooked in the collection of health statistics and less attention from researchers, policy makers, and programmers is paid to it. In Iran, no guideline has been dedicated to supporting these women and the same routine postpartum care that is common for mothers of newborns is provided for them. Moreover, studies have only looked at the frequency of stillbirth and its associated factors. For example, a study in Ahvaz investigated the incidence of intrauterine death and the factors related to it.[15] Furthermore, similar studies were conducted in Firuzabad[16] and Baboul[17] in Iran. However, no study has been found focusing on the mothers’ needs and experiences of stillbirth. As a result, considering Iran's cultural differences with other countries in coping with the grief caused by the death of the fetus, determining social support for women experiencing stillbirth and providing appropriate care is necessary. Therefore, the present study, which was part of a larger research, was conducted to explain the social support in order to improve the health of women who experienced stillbirth natively, and to integrate it into the health system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research was performed using qualitative content analysis, known as the Granheim and Longman method, through qualitative data reduction and classification.[18] Participants were 15 married women with the experience of stillbirth. They participated in semi-structured individual interviews. Purposeful sampling was conducted among volunteers and continued with a maximum variation sampling. The inclusion criteria of the study were as follows: Willingness to participate in the study, the experience of at least one stillbirth confirmed by the gynecologist in the medical record, no history of mental illness, stillbirth experienced preferably in the last 3 months, having Iranian citizenship, and being able to understand and speak the Persian language. In addition, subjects were selected from both people with known cause of stillbirth and those with unknown cause of stillbirth. Unwillingness to continue the collaboration in any phase of the study was considered as the exclusion criterion.

Mothers were identified based on records at healthcare centers and were invited for participation in the study by a phone call and after an introduction by the researcher and a brief description of the objectives was given. The interview took place at the destination and time most convenient for the participants. At the beginning of the interview, an explanation of the purposes of the study was given and a written informed consent was received. The interview started with the question, “Please talk about your experience of stillbirth” and based on the reply of the participants, was continued with the question “What support did you need during this experience?” The duration of the interviews was between 30 and 70 min. They were recorded with a tape recorder which continued until no additional data was collected. Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis. Immediately after each interview, the researchers listened to the recording and transcribed the content of the interview in Word software, and thus, formed the unit of analysis. Then, the data were read, and important phrases and expressions were determined and labeled. Similar codes were then merged and initial clustering was performed. The declining trend in the data continued in all the interviews until categories emerged.

With the help of the mentioned methods, the researcher tried to reflect the participants’ actual words in findings. Interviews were reviewed by the participants and experts of methodology, and the study content and, thus, content validity was measured. Reliability was obtained by the complete and constant registration of the researcher's activities on the method of collection, analysis, and presentation of excerpts from the interviews for each of the categories. The derived categories were given to a number of individuals, who did not participate in the study, with the same characteristics as the participants and their judgment about the similarity between research results and their experiences was assessed. In addition, the text portions of a number of the interviews, codes, and derived categories were given to the researcher's colleagues who did not participate in the study and were familiar with the analysis of qualitative research, in order to assess their agreements on the derived concepts.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Moreover, by obtaining written informed consents from the participants, allowing them to withdraw from the study, and referring them to counseling centers if they needed emotional support, ethical standards were maintained.

RESULTS

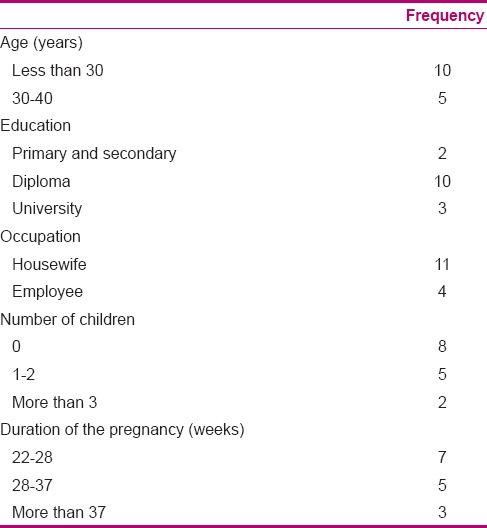

The participants consisted of 15 women who had experienced stillbirth, and were selected by purposive sampling method and compliance with the maximum variation between individuals with various causes of stillbirth, different ages, at different stages of pregnancy, and previous pregnancy and delivery experiences [Table 1]. From the analysis of the participants’ interviews, two major categories emerged and each main category included subcategories. The main categories were introduced first, and then, each subcategory was introduced based on the cited statements of the participants [Table 2]. By using qualitative content analysis method of Granheim and Longman, the interviews were read and the units of analysis were separated. One example is “Thank God! My husband was beside me when I heard the news about my fetus’ death; he comforted me and did not show his sadness, and his support made me realize I was more important for him than the child helped me accept what had happened.” “Thank God! My husband was beside me and he comforted me, this support helped me accept what had happened” was considered as a semantic unit. Then, the condensed meaning unit, which was the accompaniment and support of the husband, was determined and the empathy code was extracted. Thus, similar derived codes were placed under the category of spouse support and in the main category of support from relatives.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of participants

Table 2.

Main category and subcategories of interviews with participants

Support from relatives

The main category that women expressed regarding their health promotion in order to return to ordinary life after experiencing stillbirth was support from relatives, in other words, the support they expected from the first moment of the event until returning home. The majority of mothers said when they heard the news about their infant's death, the presence and sympathy of their husband was very helpful in accepting the incident. On the other hand, Iranian women, due to family ties, mentioned the need for family support during labor at the hospital as essential in helping them deal with the situation.

Husband support

Most participants stated that the spouse as the person closest to the mother plays an important role in supporting her. These mothers stated that it was helpful if their husbands were present when they were informed about their fetus’ death, and understood them, continued to express their love, and showed their acceptance of the event through their behavior and attitude. In other words, Iranian mothers wanted their husbands’ support and presence at the time of hearing about their fetus’ death, discharge from the hospital, and returning home and also in planning for their next pregnancy. Iranian mothers wanted their spouse to be present during hospital admission and labor, if possible, and give them emotional support. In fact, this was very effective for mothers in accepting and dealing with this incident.

A housewife aged 26 said:

“Thank God! my husband was beside me when I was informed of the death of the fetus, he comforted me and did not show his sadness, but then my brother told me that the night that I was in the hospital he had not slept and cried all night. He tried to hide it from me in that situation. His support that showed me I was more important to him than the baby helped me in the acceptance of the situation.” (Participant number 2)

Other Iranian mothers mentioned the role of support from the spouse after discharge from the hospital and in returning home in cases such as providing support during blaming of the mother by others, accompaniment during counseling, and consolation and sympathy with her, efforts to strengthen their marriage, and helping her return to public and professional life.

Support from family and friends

Many participants stated that receiving support from family and friends was very effective in gaining mental relaxation and reducing stress. Iranian women needed family support during hospitalization and felt the need for accompaniment, so that they could escape loneliness and feel sympathy. Iranian women spoke of the positive impact of relatives visiting them after discharge from the hospital and returning home in reducing their feeling of guilt.

A 32-year-old female employee said:

“When I returned home to my family and relatives came to visit me, I was calmer and did not feel guilty. My family's sympathy helped me accept the incident.” (Participant number 14)

Many participants stated that after giving birth, due to their mental condition, they were unable to perform everyday tasks and even self-care, and this condition made life difficult for their husbands and children and aggravated their guilt. They suggested that their family and friends, in addition to comforting them, had an important role in helping them perform daily activities and housekeeping and return to their normal lives.

The social support systems

Many participants stated that the loss of the fetus can quickly lead to mental vulnerability. In addition, intervention and counseling support were important needs for these women to adapt to the circumstances in order to provide their mental health needs after delivery. On the other hand, support and suitable counseling from the moment that the mother is informed until the next pregnancy can be very effective in the grieving process, facilitate acceptance of the issue, and reduce stress.

Economic support

Many participants remarked that if they were aware of the cause of the death of the fetus, they would experience less stress, but due to poor economic conditions, they were not able to do the tests and canceled them. A 25-year-old housewife said:

“I would like to know why my child died; if I knew I would not have much stress in my next pregnancy and would not feel guilty.” (Participant number 8)

It seems that support from the hospital social aid system in the funding of a fetal autopsy could help in improving the mental health of these patients. On the other hand, many participants felt the need to visit a counselor, but because they could not afford the costs, they avoided it. A 27-year-old housewife said:

“May be if I went to counseling I would recover faster, but unfortunately I could not pay the costs. I wish there were governmental counseling centers, so the costs would be less.” (Participant number 10)

According to participants’ comments, it appears that offering advisory services in hospitals and health centers is an essential need of the mothers.

Support from healthcare centers

Many participants and Iranian mothers stated that at the time of delivery at the hospital, they had so much stress that they forgot about the training they were given by the medical staff. They did not know when to refer for postpartum visit and what kind of care they needed after delivery. They expressed that they wanted follow-up from the health center that provided them with care services during pregnancy and had their family records, so that while receiving care from the medical team, their mental health problems would be identified and they would be referred to counseling centers. A 30-year-old employed mother said:

“I was feeling so bad and I was so upset that I forgot everything the doctor had taught me. I even lost the information brochures. I think it was the duty of the prenatal care provider to follow-up and ask why I had not referred for healthcare.” (Participant number 6)

Peer support

Many participants stated that if they had met a mother who had had the same experience and had seen her success in passing these difficult stages and having a successful pregnancy after stillbirth, the acceptance of fetal death and adaptation to these conditions would have been easier. A 28-year-old employed mother said:

“I wish to see and talk to mothers who have had the same experience as me, but have been able to overcome this situation. Seeing them would make me hopeful.” (Participant number 2)

DISCUSSION

This study was performed in Iran for the first time to explain the social support needed to improve the health of mothers after they experience stillbirth. Categories extracted showed the kind of suitable support that can improve the health of women who have experienced stillbirth. The study findings showed that providing social support for women helped them in coping with the grief caused by the death of the fetus. Many of these women reported that receiving emotional support from relatives was effective in the acceptance of and adaptation to the issue. The women participating in this study indicated that receiving emotional support from their spouse, as the closest person to them, was very effective in their mental health. In fact, sharing the feelings of grief for the lost baby brings them closer to each other. The study findings of Toller and Braithwaite suggested that parents need each other to mourn their dead fetus.[19] On the other hand, these mothers indicated that their spouse, by showing sympathy and interest, which indicated the acceptance of the dead fetus, helped reduce their feeling of guilt. In this regard, the findings of the study by Avelin et al. indicated that although it seems that couples had different style and manner of mourning for the dead child, most of these couples will be able to accept and respect each other.[20] However, after this experience, most mothers wished to express their grief loud and clear, otherwise it would be difficult for them to experience the grief of losing a child and share it with their spouse. Vance et al. stated that the quality of a couple's relationship can affect each couple's response to fetal death. In cases where there is satisfaction in the couple's relationship, the bereaved mother's mental health is better, and in fact, the supportive relationship will help in adapting to the death.[21] Surkan et al. stated that if after the fetal death, the father refuses to talk to the mother, postpartum depression would be twice as likely to occur and an appropriate relationship has a supportive aspect.[22]

Family support was one of the needs of mothers in order to accept the death of the fetus. As Shreffler et al. had stated, the impact of this event is broad, it affects the father, brother, or sister who were waiting for the birth of the baby, and even the healthcare providers share the mother's grief.[23] Säflund and Sjögren also stated that family members’ conversation about the stillbirth can help them in sharing their experiences.[24]

The results show that fetal death is a debilitating experience and results in loss of power and loneliness. These mothers mentioned that meeting people who have had the same experience in the past and hearing their stories in dealing with the event, the treatment they received, and returning to normal life were their supportive needs. Cacciatorestated that in support groups where members express and share their stories, the process of adaptation to trauma can be developed. This relationship between two or more people with similar experiences helps the bereaved person to create meaning for her experience.[11] Roehrs et al. mentioned that some participants discussed the difficulty in talking about their experience with friends and family and stated the benefits of support from peer groups at the time of crisis and even in the coming years.[25]

Consultation requirements in respect to improvement of the mental health of the mother were found to be a supportive need of the mothers. Kuti stated that consultations for bereaved parents of a dead baby provide an opportunity to assess their mental health status.[1]

Most mothers experiencing stillbirth mentioned that knowing the cause of death was an affective factor in the reduction of psychological stress, especially in later pregnancies. Iranian women reported the need for financial assistance in order to perform an autopsy. Britain's Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists stated that investigation after stillbirth is one of the most useful actions to provide information for the parents about their child's cause of death. Most international care guidelines on stillbirth recommend high-quality studies on fetal death and suggest that such studies be provided to all parents who experience stillbirth, so that they can make a decision on whether to take such surveys or not. It should be noted that studies on stillbirth do not only have diagnostic benefits but also lead to improved emotional outcomes for both mothers and fathers.[13]

Many mothers commented that they need support from health centers and care workers to gain information on the care needed for future pregnancies. In fact, many of these women mentioned the need for follow-up by healthcare providers after delivery for the diagnosis of mental disorders and referral to counselors, if needed, as necessary support after delivery. The findings of Saflund and Wredling showed that parents recognized the important role of healthcare providers. These parents stated that the midwife and doctor's recommendations had a great impact on their ability to adapt with the death of their fetus.[26]

CONCLUSION

It seems, however, that fetal and infant mortality rates have declined slowly over time by the increase in prenatal care quality, but still as an adverse outcome of pregnancy, it has significant psychological effects on parents. Investigating the extracted main categories of this study indicated that health centers’ current approach in providing services to mothers who experienced stillbirth needs to change and improve in a way that it can improve the health of these mothers and comprehensively support and strengthen the foundation of the family. Thus, health services’ planning, especially for mothers grieving the loss of a child, should focus on support services and counseling with the approach of empathy from the moment the mother is informed until she achieves a stable mental condition. Moreover, this goal can be achieved through designing informing methods, appropriate training, and coordination of care, especially with counseling and social aid centers. It is suggested that the findings of this study be used in designing care guidelines for medical staff in order to teach the appropriate use of psychological support and counseling to promote the mental health of mothers and Iranian families experiencing stillbirth. Thus, a step can be taken toward reducing the long-term psychological effects on mothers and their families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article was derived from Ph.D research of the first author “maryam allahdadian” with project number 392472, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, We hereby express our gratitude to the Research Deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their support and funding of this project. The cooperation of individual participants is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuti O, Ilesanmi CE. Experiences and needs of Nigerian women after stillbirth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113:205–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacciatore J. Stillbirth: Patient-centered Psychosocial Care. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:691–9. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181eba1c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray Cunninyham F, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Gillstrap LC, Wenstrom KD. In: Obstetrics W, editor. New York: McGrowHil; 2009. pp. 677–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condon JT. Prevention of emotional disability following stillbirth-the role of the obstetric team. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;27:323–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1987.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacciatore J. Psychological effects of stillbirth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold KJ, Sen A, Hayward RA. Marriage and cohabitation outcomes after pregnancy loss. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1202–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehman D, Ellard J, Wortman C. Social support for the bereaved: Recipients’ and providers’ perspectives on what is helpful. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:438–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacciatore J, Schnebly S, Froen F. The effects of social support on maternal anxiety and depression after the death of a child. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17:167–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher P. Experiences in family bereavement. Fam Community Health. 2002;1:57–70. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downe S, Kingdon C, Kennedy R, Norwell H, McLaughlin MJ, Heazell AE. Post-mortem examination after stillbirth: Views of UK-based practitioners. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacciatore J. Effects of support groups on posttraumatic stress responses in women experiencing stillbirth. Omega (Westport) 2007;55:71–90. doi: 10.2190/M447-1X11-6566-8042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stock SJ, Goldsmith L, Evans MJ, Laing IA. Interventions to improve rates of postmortem examination after stillbirth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153:148–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cacciatore J, Erlandsson K, Rådestad I. Fatherhood and suffering: A qualitative exploration of Swedish men's experiences of care after the death of a baby. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:664–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. London: Leicester; 2007. The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Full guideline; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarei R, Athari F, Aghaei N. Prevalence and factors associated with intrauterine death among patients referred to Imam Khomeini hospital of Ahwaz. J Med Sci. 2009;8:438. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiasi T, Jhanfar SH, Mokhtarshahy S, Hqhany H. Evaluation of maternal risk factors for intrauterine fetal death in women admitted to hospital Firuzabad during 1999-2003. Nurs Faslnameh Iran. 2003;62:33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasha H, Faramarzi M, Bakhtiari A, Allah-Hajian K. Stillbirth and associated factors. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2000;2:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toller PW, Braithwaite DO. Grieving together and apart: Bereaved parents’ contradictions of marital interaction. J Appl Commun Res. 2009;37:257–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avelin P, Rådestad I, Säflund K, Wredling R, Erlandsson K. Parental grief and relationships after the loss of a stillborn baby. Midwifery. 2013;29:668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vance JC, Boyle FM, Najman JM, Thearle MJ. Couple distress after sudden infant or perinatal death: A 30-month follow up. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:368–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surkan PJ, Rådestad I, Cnattingius S, Steineck G, Dickman PW. Social support after stillbirth for prevention of maternal depression. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:1358–64. doi: 10.3109/00016340903317974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shreffler K, Hill T, Cacciatore J. The impact of infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, and child death on marital dissolution. J Divorce Remarriage. 2012;53:107. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Säflund K, Sjögren B, Wredling R. The role of caregivers after a stillbirth: Views and experiences of parents. Birth. 2004;31:132–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roehrs C, Masterson A, Alles R, Witt C, Rutt P. Caring for Families Coping With Perinatal Loss. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:631–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saflund K, Wredling R. Differences within couples’ experience of their hospital care and well-being three months after experiencing a stillbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1193–9. doi: 10.1080/00016340600804605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]