Abstract

The reduction in global neonatal mortality rates remains a challenge. Internationally recognized protocols for hospital care of sick and small newborns are limited, although this specialized area lends itself to standardization. An interdisciplinary team including international and local clinical experts worked with the Rwandan Ministry of Health and Rwandan professional associations to develop and implement a neonatal care program in a rural Rwandan district hospital that was ultimately accepted as the national standard for newborn medicine. Successful features and challenges are discussed. It is realistic to develop, implement and disseminate neonatal protocols for sick newborns.

Keywords: newborn medicine, global health, implementation

Abstract

La réduction des taux de la mortalité néonatale dans le monde reste un défi. Les protocoles internationalement reconnus en matière de soins hospitaliers aux nouveau-nés malades et petits sont limités, bien que ce domaine spécialisé se prête à la standardisation. Une équipe interdisciplinaire comprenant des experts cliniques internationaux et locaux a travaillé avec le Ministère de la Santé du Rwanda et des associations professionnelles rwandaises afin d’élaborer et mettre en œuvre un programme de soins néonataux dans un hôpital de district Rwandais ; celui-ci a finalement été accepté comme standard national en matière de médecine du nouveau-né. On discute des caractéristiques qui ont fait le succès du programme et des défis restants. Il est réaliste d’élaborer, de mettre en œuvre et de diffuser des protocoles néonataux pour les nouveau-nés malades.

Abstract

La disminución de la mortalidad neonatal mundial sigue planteando dificultades. Existen pocos protocolos de tratamiento hospitalario de los recién nacidos enfermos y pequeños para la edad gestacional que sean reconocidos internacionalmente, pese a que esta esfera de especialización se presta a la normalización. Un equipo interdisciplinario conformado por expertos clínicos nacionales e internacionales trabajó en colaboración con el Ministerio de Salud de Rwanda y las asociaciones ruandesas de profesionales, con el objeto de establecer un programa de atención neonatal en el hospital distrital de una zona rural del país. En último término, este programa se aceptó como la norma nacional en materia de atención médica del recién nacido. En el presente artículo se analizan los aspectos que han dado buenos resultados y las dificultades que se encontraron durante la ejecución del programa. El proyecto de elaboración, ejecución y difusión de protocolos de tratamiento de las enfermedades de los recién nacidos constituye una intervención realista.

Globally, 2.9 million neonates die each year, amounting to 43% of under-five mortality. Three quarters of these newborns die in their first week, one third on their first day.1,2 With 99% of neonatal deaths occurring in developing countries, sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia are the most greatly affected.

Significant progress has been made towards reducing the world’s under-five mortality rate; however, the least reduction has occurred in neonatal mortality, resulting globally in a 17% rise in the neonatal component of under-five mortality from 1990 to 2012.1 Extra care of infants with low birth weight (LBW) is estimated to reduce neonatal mortality by 20–40%.3

There are currently limited internationally recognized protocols for the subspecialized area of newborn medicine.4–7 Although there are wide variations in many aspects of medical care by location, the basic care of sick newborns can be relatively standardized. We describe the development and implementation of a newborn medicine program in a district hospital in rural Rwanda, and present a neonatal care package of protocols, medical records with order sets, and quality indicators. The package is designed to provide effective, feasible newborn health care tailored to resource-limited settings.

SETTING

Located in East Africa, Rwanda has a population of 10.5 million,8 82% of whom live on less than US$2 per day.8 The Rwinkwavu District Hospital (RDH) is located in Kayonza, a rural district in the south-east of the country with a population of 346 751.9 RDH has approximately 1875 deliveries and 460 neonatal admissions annually coming from maternity or emergency wards, health centers or homes (source: Rwanda Health Maintenance Information System, 2008–2011).

In its mission to ensure universal access to affordable health service of the highest attainable quality the government of Rwanda has prioritized improving its population’s health. Through these efforts, the Rwandan health care system has significantly reduced the under-five mortality rate, including the infant mortality rate (IMR), which fell by 41%10 from 2005 to 2010.11 During this period, the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) fell by only 27%, from 37 to 27 per 1000,11 causing the neonatal component of the IMR to rise by 11%.

Partners In Health (PIH), a Boston-based global health organization, began working in Rwanda at the invitation of the Rwanda Ministry of Health (MOH) in 2005 to strengthen the health care delivery system in selected remote and underserved districts in Rwanda. At the request of the MOH, a multidisciplinary team of specialists from PIH, Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH), partner organizations, and Rwandan professional associations was established to develop and implement a neonatal package at RDH.

ASPECT OF INTEREST

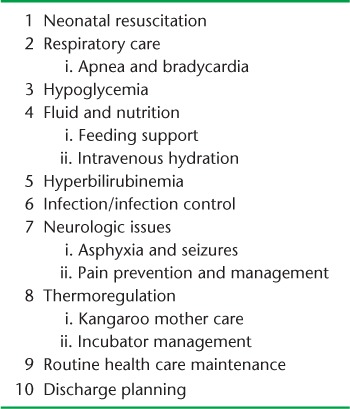

First, the package was drafted by the interdisciplinary team. The package consisted of a protocol with 10 modules (Table 1, http://www.childrenshospital.org/~/media/research-and-innovation/divisions/newborn-medicine/neonatalprotocolsrwanda.ashx), teaching materials, medical record/order sets (Appendix), and quality indicators. Over a 2-month period in 2010, specialist trainers taught weekly formal training courses to on-site MOH general practitioners and nurses, covering the most critical concepts in the protocol. The package was also introduced on the pediatric ward where trainers, acting as consultants, attended daily neonatal rounds with the staff. During this implementation phase, the neonatal care package was modified based on clinical, educational and system issues encountered to further adapt it to the local context.

TABLE 1.

Neonatal protocol modules

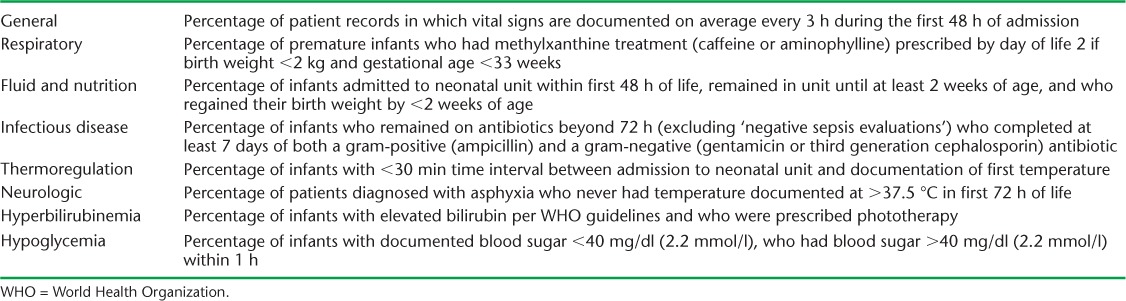

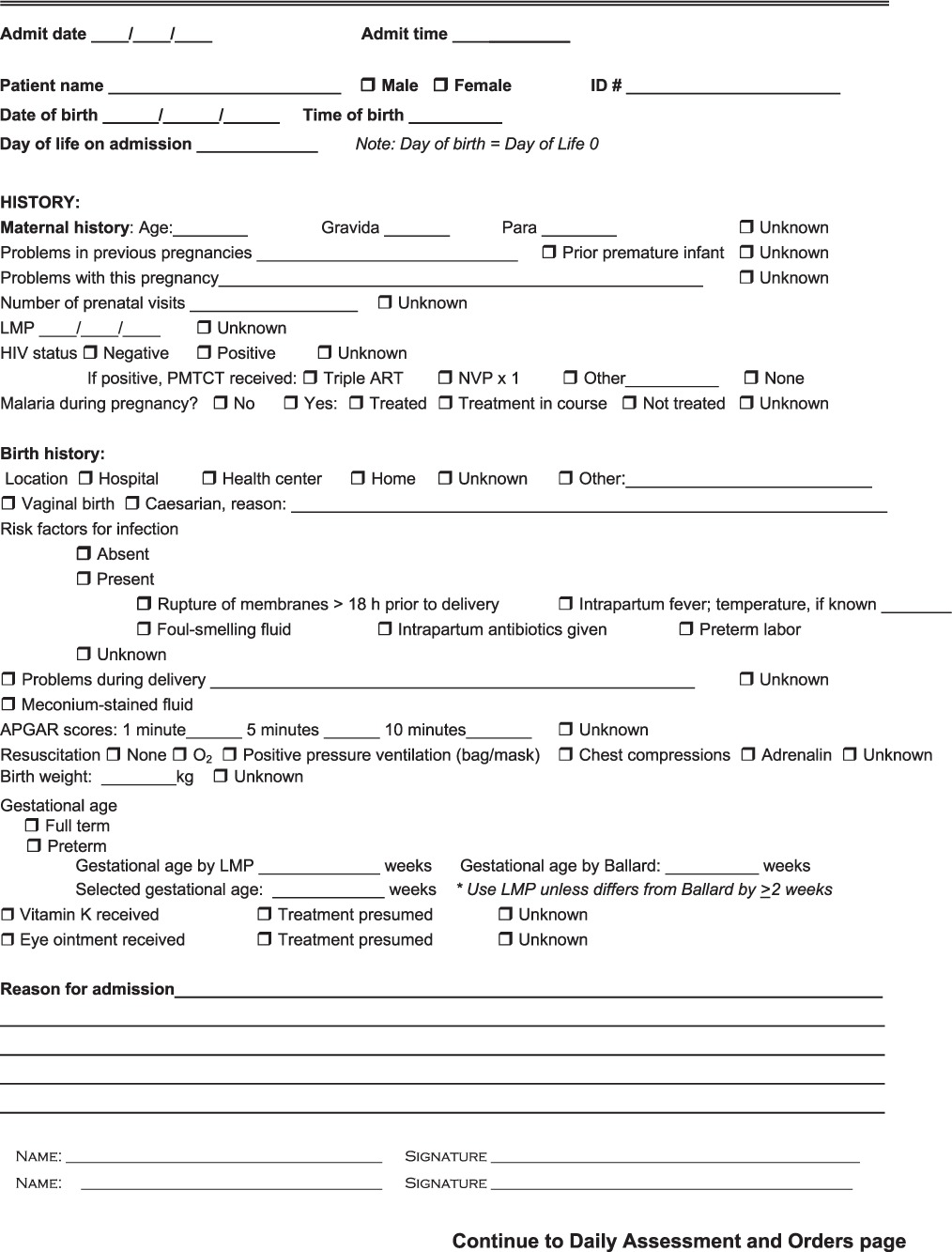

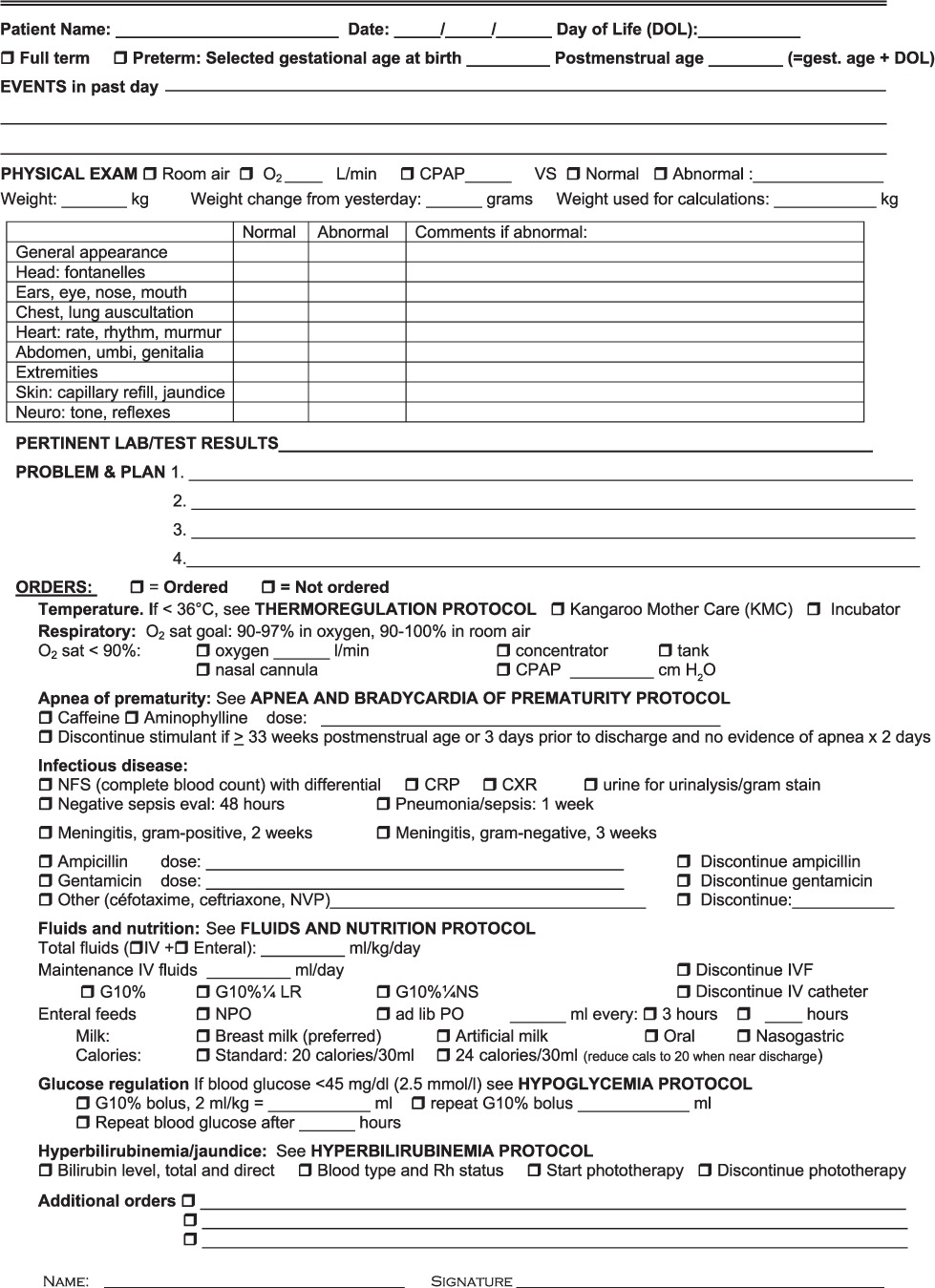

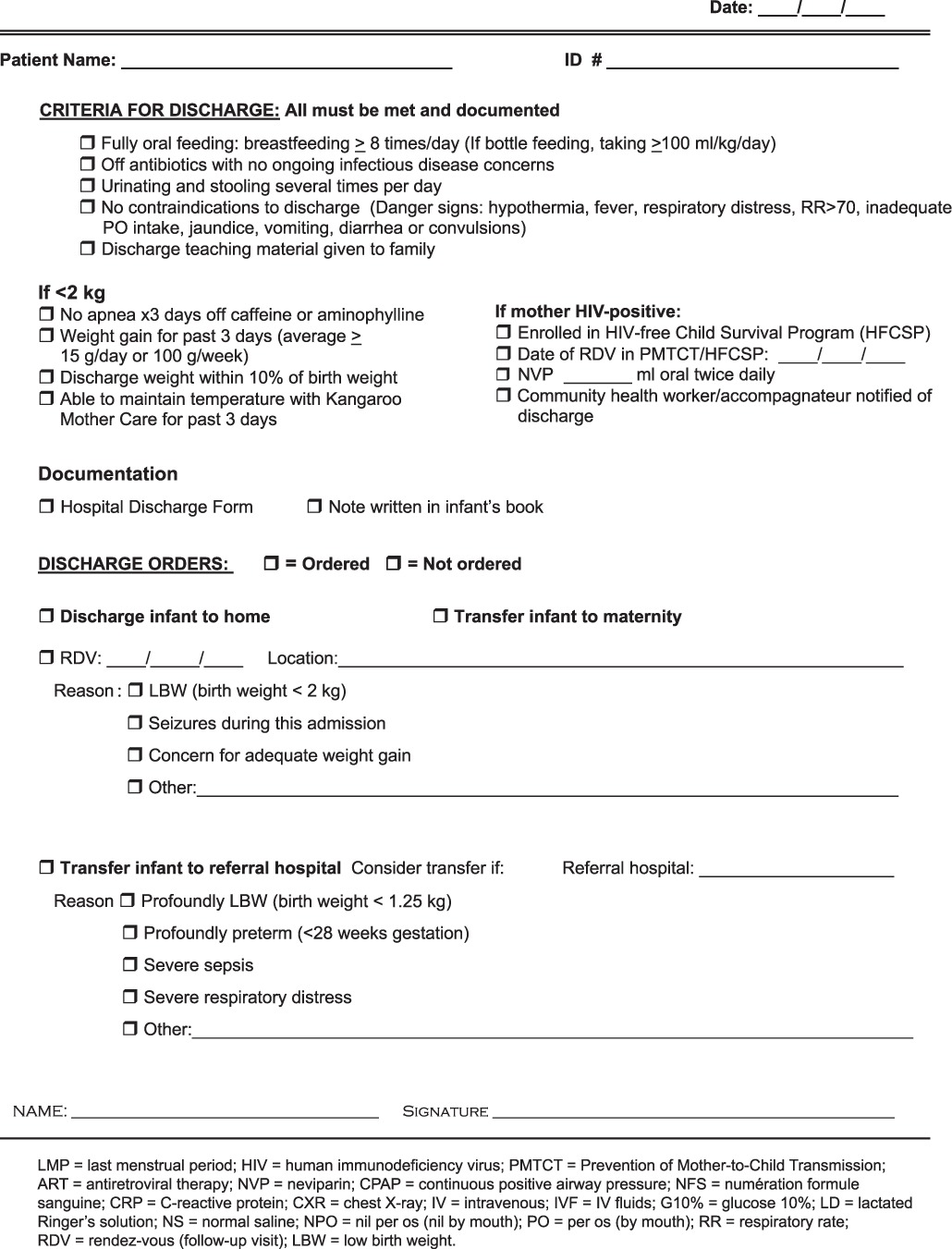

The medical record form/order set was created for admission, daily progress, and discharge documentation. The forms included prompts for key protocol items. Quality indicators were initially drafted based on expert opinion and literature review, and later modified to address topics identified as challenging by hospital staff (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Quality indicators

After this initial formative phase, the package was presented and further adapted by other key stakeholders, including the Rwanda Pediatric Association, prior to validation, national adoption and scale-up.12

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, and Rwanda National Ethics Committee, Kigali, Rwanda.

DISCUSSION

To reduce the number of neonatal deaths, early care of sick newborns in resource-limited settings should be addressed. Neonatal care requires specialty training to address specific clinical and patient safety issues that are distinct from general pediatric care. Based on our collaboration, we developed and implemented a standardized, evidence-based package of protocols for sick newborns that was aligned with a medical record format that prompted better choices in medical care, and quality indicators allowing for gap identification and improvement efforts.

The partnership between the Rwanda MOH, PIH and BCH has continued, enabling us to identify and address challenges encountered through ongoing training and mentorship, and observe adherence to the protocols and increased optimism and staff morale.

Successful features

Creating a multidisciplinary team that combined committed local physicians and nurses with technical experts enabled us to learn together and adapt the package locally. The effort encouraged system-based changes, such as procuring critical medications and equipment at the national level. Specifically, the program led to national advocacy for caffeine citrate, incubators, warming lights, glucometers with strips, and alcohol-based hand sanitizers to be added to the hospital supply chain. The introduction of the neonatal care package pushed advancement in necessary systems to achieve high-quality care at scale.

Implementation challenges

Although we were able to retain a consistent and dedicated core team, staff turnover and internal transfers led to ongoing training needs for new staff; on-site mentorship was critical in meeting this need. Competing clinical demands made it difficult to assemble all providers for classroom training simultaneously; flexible solutions such as make-up classes and private tutorials were therefore necessary. Strong local partnerships providing ongoing clinical and educational support after this initial implementation have helped provide this ongoing training and mentorship.

CONCLUSION

Our experience demonstrates that it is realistic to develop, implement and disseminate a newborn medicine program in a resource-limited setting. National prioritization and strong local and global partnerships were essential to this success. Components of the neonatal care package and lessons learnt could be of relevance to policy makers and health care professionals in similar settings. We have subsequently introduced continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to selected district hospitals. A second edition of the protocol is underway, including the use of CPAP; more advanced material necessitated by the survival of smaller, sicker newborns; and modifications based on user feedback. Continued prioritization of newborn care services at health care facilities is essential to improving neonatal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank F Ngabo, Director of Maternal Child Health at the Rwanda Ministry of Health (MOH; Kigali, Rwanda), and V Mivumbi, Rwanda MOH Neonatal Focal Point, for their invaluable guidance throughout the implementation process and ongoing leadership in advancing neonatal health. We would also like to thank S Stulac for her assistance with neonatal care package content.

This work was supported by the Harvard University Milton Fund, Cambridge, MA, USA. Competing interests: none declared.

APPENDIX:

NEONATAL UNIT MEDICAL RECORD ADMISSION FORM FOR INFANTS < 1 MONTH OF AGE

NEONATAL UNIT MEDICAL RECORD DAILY ASSESSMENT AND ORDERS

NEONATAL UNIT MEDICAL RECORD DAY OF DISCHARGE ORDERS

References

- 1.Lawn J E, Blencowe H, Oza S. Every newborn: progress, priorities and potential beyond survival. Lancet. 2014;384:189–205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60496-7. et al, for The Lancet Every Newborn Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Save the Children. State of the world’s mothers 2013: surviving the first day. Westport, CT, USA: Save the Children USA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul V K. The current state of newborn health in low-income countries and the way forward. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck D, Ganges F, Goldman S, Long P. Saving newborn lives: care of the newborn reference manual. Washington, DC, USA: Save the Children US; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Managing newborn problems: a guide for doctors, nurses and midwives. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. The NISR Home Page. http://statistics.gov.rw.

- 9.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. 2012 Population and Housing Census. Kigali, Rwanda: NISR; 2012. http://www.statistics.gov.rw/publications/2012-population-and-housing-census-provisional-results. Accessed January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer P E, Nutt C T, Wagner C M et al. Reduced premature mortality in Rwanda: lessons from success. BMJ. 2013;346:f65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f65. Erratum in: BMJ 2013; 346: f534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2010: Preliminary Report. Kigali, Rwanda: NISR; 2010. http://statistics.gov.rw/publications/rwanda-demographic-and-health-survey-2010-preliminary-report. Accessed January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rwanda Ministry of Health. National neonatal protocols. Kigali, Rwanda: MOH; 2011. [Google Scholar]