Abstract

Setting: All multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) patients who had completed 6 months of treatment under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) in Uttar Pradesh, the largest state in northern India.

Objective: To determine the proportion of MDR-TB patients with regular follow-up examinations, and underlying provider and patient perspectives of follow-up services.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was undertaken involving record reviews of 64 eligible MDR-TB patients registered during April–June 2013 in 11 districts of the state. Patients and programme personnel from the selected districts were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire.

Results: A total of 34 (53.1%) patients underwent follow-up sputum culture at month 3, 43 (67.2%) at month 4, 36 (56.3%) at month 5 and 37 (57.8%) at month 6. Themes associated with irregular follow-up that emerged from the interviews were multiple visits, long travel distances, shortages of equipment at the facility and lack of knowledge among patients regarding the follow-up schedule.

Conclusion: The majority of the MDR-TB patients had irregular follow-up visits. Provider-related factors outweigh patient-related factors on the poor follow-up examinations. The programme should focus on the decentralisation of follow-up services and ensure logistics and patient-centred counselling to improve the regularisation of follow up.

Keywords: SORT IT, MDR-TB, follow-up, India

Abstract

Contexte : Tous les patients atteints de tuberculose multirésistante (TB-MDR) qui avaient achevé 6 mois de traitement dans le cadre du Programme National Révisé de Lutte contre la Tuberculose (RNTCP) dans l’Uttar Pradesh, le plus grand état dans le nord de l’Inde.

Objectif : Déterminer la proportion de patients TB-MDR bénéficiant d’examens de suivi régulier et la vision des prestataires et des patients sur ces services de suivi.

Méthodes : Une étude rétrospective de cohorte a été réalisée grâce à la revue des dossiers de 64 patients TB-MDR éligibles enregistrés entre avril et juin 2013 dans 11 districts de l’état. Les patients et le personnel du RNTCP des districts sélectionnés ont également été interviewés grâce à un questionnaire semi-structuré.

Résultats : Au total, 34 (53,1%) patients ont bénéficié d’examens de culture de crachats au 3e mois, 43 (67,2%) au 4e mois, 36 (56,3%) au 5e mois et 37 (57,8%) au 6e mois. Les principaux facteurs associés à un suivi irrégulier émanant des entretiens étaient le nombre élevé de consultations, la distance à parcourir, les ruptures de stock dans les structures et le manque de connaissances des patients vis-à-vis du programme de suivi.

Conclusion : La majorité des patients TB-MDR ont eu un suivi irrégulier. Les facteurs liés aux prestataires dépassent ceux liés aux patients en matière d’examens de suivi médiocres. Le RNTCP devrait se concentrer sur la décentralisation des services de suivi, assurer la logistique et le conseil centré sur le patient afin d’accroitre la régularité du suivi.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de tuberculosis multidrogorresistente (TB-MDR) después de haber completado los 6 meses de tratamiento en el contexto del Programa Nacional de Control de la Tuberculosis (RNTCP) en Uttar Pradesh, la provincia más grande del norte de la India.

Objetivo: Determinar la proporción de pacientes con TB-MDR en quienes se practicaron exámenes periódicos de seguimiento y conocer las opiniones de los profesionales y de los pacientes sobre los servicios de seguimiento.

Métodos: Se llevó a cabo un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo a partir del examen de las historias clínicas de 64 pacientes con diagnóstico de TB-MDR, que cumplían con los requisitos de inclusión, registrados entre abril y junio del 2013 en 11 distritos del estado. Se realizaron además entrevistas a los pacientes y al personal del RNTCP de algunos distritos mediante un cuestionario semi-estructurado.

Resultados: En 34 pacientes se practicó el seguimiento del cultivo de esputo al tercer mes (53,1%), en 43 casos al cuarto mes (67,2%), en 36 al quinto mes (56,3%) y en 37 pacientes al sexto mes de tratamiento (57,8%). Los principales factores asociados con la irregularidad del seguimiento que revelaron las entrevistas fueron la multiplicidad de las citas, la larga distancia de los desplazamientos, la carencia de insumos en los centros y el desconocimiento del calendario del seguimiento por parte de los pacientes.

Conclusión: El seguimiento de la mayoría de los pacientes con diagnóstico de TB-MDR fue irregular. En las causas de la deficiencia del seguimiento predominaron los factores dependientes de los profesionales en comparación con los factores propios a los pacientes. El RNTCP debe considerar seriamente la descentralización de los servicios de seguimiento, suministrarlos materiales necesarios y proveer una orientación centrada en los pacientes con el objeto de mejorar la regularidad de los seguimientos.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major public health problem worldwide, and the situation is worsening with the rise in multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). India has the second highest burden of MDR-TB cases after China, and reported approximately 66 000 MDR-TB cases among notified pulmonary TB cases in 2011.1 The programmatic management of drug-resistant TB (PMDT) was implemented in a phased manner from 2007 onwards, and it has now been scaled up to all states in India.2

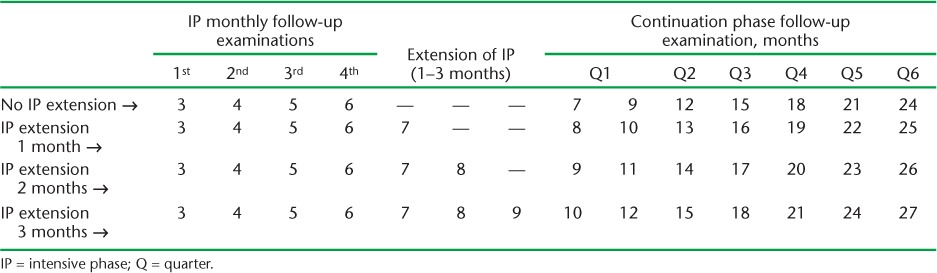

The PMDT guidelines recommend that after confirmation of MDR-TB the patient should immediately be started on a 6–9 month intensive phase of treatment with six drugs, followed by an 18-month continuation phase with four drugs.2 MDR-TB patients on treatment should also undergo regular follow-up evaluations for clinical, microbiological and radiological response to treatment. Follow-up examinations include measurement of weight, estimation of serum creatinine, sputum culture examination and chest radiography (CXR) at monthly intervals during the intensive phase and at 3-monthly intervals during the continuation phase until the end of treatment (Table 1).2

TABLE 1.

Schedule for culture and drug susceptibility testing among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis follow-up examinations under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme

Regular monitoring of patients is necessary to ensure early recognition of adverse effects, better adherence to treatment and early identification of extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), which can lead to favourable treatment outcomes. Sputum culture is performed to evaluate the microbiological response to treatment, to progress treatment from the intensive to the continuation phase, i.e., from six drugs to four drugs, and for early identification of failure with the MDR-TB treatment.

Few data are available on adherence to follow-up examinations, timeliness of follow-up visits and timely progression from the intensive phase to the continuation phase under programmatic settings. There is also a poor understanding of programmatic and patient-related factors associated with irregular follow up. We conducted a study to determine the proportion of MDR-TB patients undergoing regular follow-up examinations and underlying provider and patient perspectives on follow-up services.

METHODS

Study design

This mixed-method study had a quantitative and a qualitative component. The quantitative component was a retrospective cohort study of all MDR-TB patients registered in 11 districts of Uttar Pradesh during April to June 2013, involving review of records and reports routinely maintained by the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). Under the qualitative component, in-depth interviews using semi-structured questionnaires were conducted among a sample of patients and RNTCP personnel in each of the districts and coded to identify major themes in barriers to regular follow-up. On purposive sampling, a total of 12 patients and 11 programme personnel participated in the study and were subsequently interviewed. Semi-structured interview guides were developed with the following previously identified domains: knowledge about the monitoring schedule for MDR-TB treatment, availability of PMDT services in the district and reasons for poor follow-up.

Study settings

The state of Uttar Pradesh, one of the largest, most populous states of India, has 75 districts and a population of 205.7 million, with varied topography and socio-economic conditions. Health care services are delivered through both public and private sectors. For effective RNTCP implementation, there are 478 TB units (1 TB unit covers a population of approximately 0.5 million) and 1863 designated microscopy centres (1 DMC for a population of 0.1 million) to provide appropriate TB services. The state has two public sector intermediate reference laboratories (IRLs) with culture and drug susceptibility testing (CDST) facilities, four other-sector laboratories with RNTCP-accredited CDST facilities and six Xpert® MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) machines to diagnose and follow-up presumptive and diagnosed MDR-TB patients.

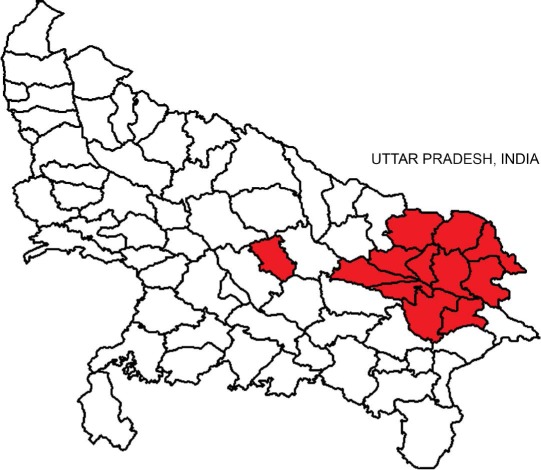

The present study was conducted at 11 districts where PMDT services were delivered through one IRL and two drug-resistant TB centres (DR-TB centres).

Study population and study period

All MDR-TB patients registered during April–June 2013 in the 11 districts were included. The map of the state with selected districts is shown in the Figure. Those patients who were transferred into the study area after taking >1 month of MDR-TB treatment elsewhere and those who did not complete the initial 6-month intensive phase of treatment were not included in the study, as complete follow-up details could not be obtained from these groups of patients.

FIGURE.

Map of Uttar Pradesh State showing the 11 districts included in the study.

Data variables, sources and collection

Quantitative data were collected from PMDT treatment cards, the referral for CDST register and the PMDT TB registers. Variables collected included the PMDT TB number, age, sex, date of treatment initiation, monthly weight and serum creatinine recordings, date of sputum culture, CXR and adverse drug reactions.

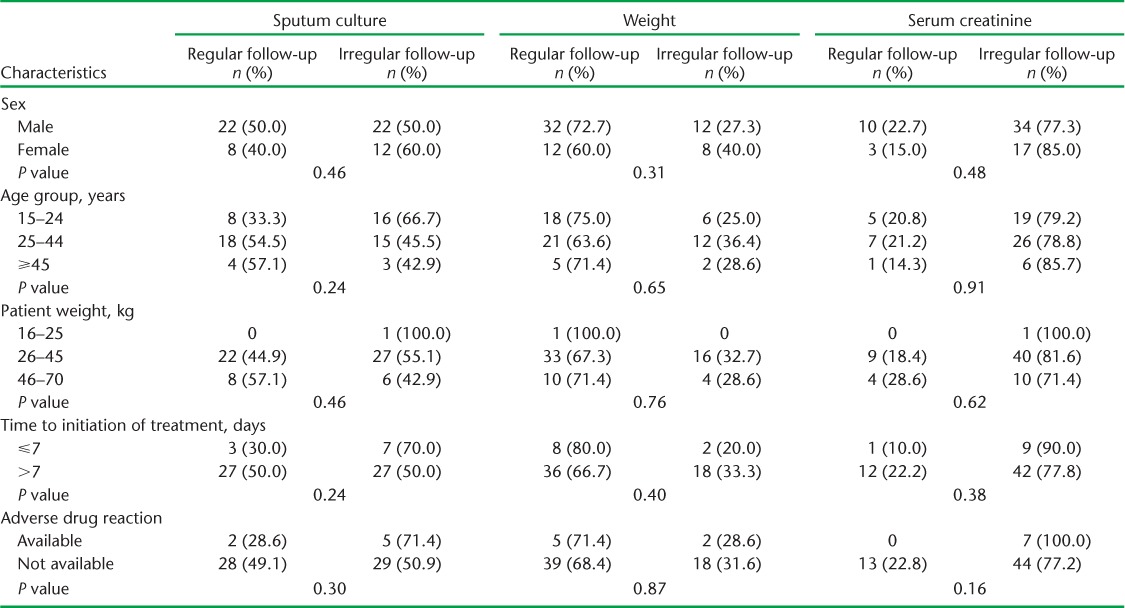

Key RNTCP personnel and patients in each district were interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide to ascertain the gaps and mechanisms adopted for effective supervision and monitoring of MDR-TB follow-up patients. For the purpose of the study, to determine the quality of the follow-up examinations, operational definitions for ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ follow-up were framed for each follow-up examination separately for weight, serum creatinine and sputum culture. A patient with five or more weight measurements during the first 6 months of treatment was defined as undergoing regular follow-up. Similarly, a patient with ⩾3 serum creatinine examinations or ⩾3 sputum culture examinations was defined as regular follow-up for creatinine and sputum examination, respectively. Patients who did not meet these criteria were recorded as irregular follow-up.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were entered into a structured data entry format created in EpiData and analysed using EpiData analysis software (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Descriptive statistical measures such as percentages were used to estimate the proportion of follow-up examinations performed and the proportion of MDR-TB patients who received regular follow-up. Cross-tabulations were made of the exposure (socio-demographic variables of MDR-TB patients) and outcome variables (follow-up examination, whether optimal or not, separately for weight, serum creatinine and sputum culture) and the significance of the association was measured using the χ2 test.

Qualitative analyses were based on principles of grounded theory, which utilises transcripts and field notes to develop theoretical concepts about the event under study.3 Interviews were conducted by a native Hindi speaker under the supervision of the principal investigator who prepared the notes, after which themes and sub-themes related to barriers to regular follow-up were identified.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Permission was also sought from the relevant state programme authorities. The requirement for informed consent for the patient record review was waived by the ethics committee, as it did not involve direct interaction with the patient. However, informed consent was obtained before the in-depth interviews with patients and health care providers using a structured consent form.

RESULTS

Of the 79 MDR-TB patients registered in 11 districts in Uttar Pradesh during the study period, 57 (72.2%) were males and the majority (n = 60, 75.9%) were in the 25–44 years age group. After completion of 6 months of MDR-TB treatment, 64 (81%) patients were still on treatment, 7 (8.9%) had died and 8 (10.1%) were lost to follow up.

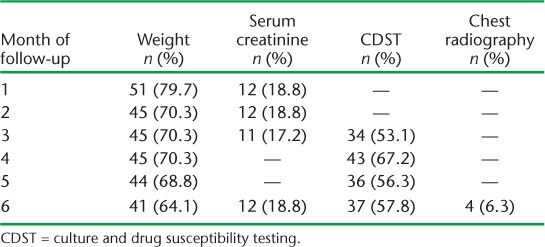

The monthly follow-up examinations during the 6-month treatment period are shown in Table 2. While nearly 51 (79.7%) patients had their weight recorded during the first month, only 41 (64.1%) were weighed at month 6. Only one sixth of the patients had serum creatinine examinations at month 1; this number decreased in subsequent months. Sputum culture from month 3 onwards was performed for only around half of the patients, while CXR was performed for only four (6.3%) patients. A total of 34 (53.1%) patients had a follow-up sputum culture examination at month 3, 43 (67.2%) at month 4, 36 (56.3%) at month 5 and 37 (57.8%) at month 6 (Table 2). Six (9.4%) and seven (10.9%) respondents underwent all three follow-up examinations (weight, serum creatinine, sputum culture) during the third and sixth month, respectively. Only three (4.7%) had all four follow-up examinations (weight, creatinine, culture and X-ray) in the sixth month (data not shown). There is no significant difference between socio-demographic and clinical parameters and follow-up examinations such as weight, sputum culture and serum creatinine (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients undergoing follow-up examinations in 11 districts of Uttar Pradesh, India, April–June 2013 (n = 64)

TABLE 3.

Association between socio-demographic factors and follow-up and sputum culture, weight and serum creatinine among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in 11 districts of Uttar Pradesh, India, April–June 2013

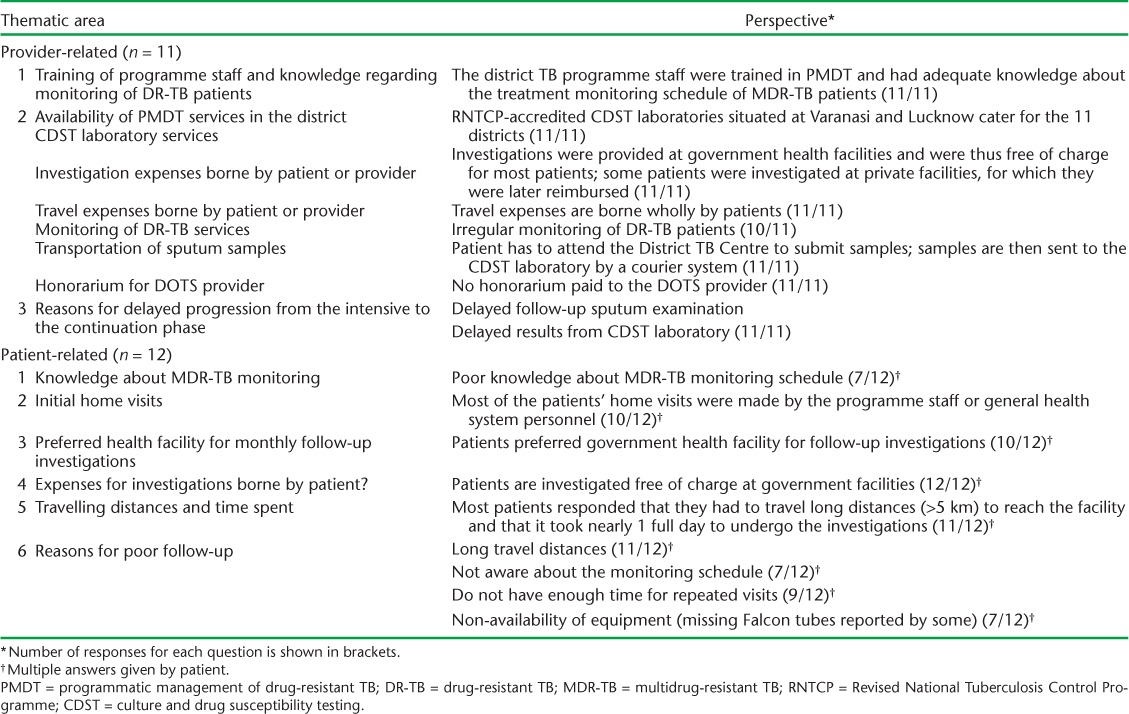

Perceptions of key programme personnel about treatment follow-up

In-depth interviews were conducted with 11 TB care providers, one provider from each of the selected districts (Table 4). The key programme staff felt that there was a lack of commitment on the part of the programme to ensure regular follow-up examinations, with the focus being on treatment alone. Although investigations are provided free of charge at government facilities, the patients have to bear the travel expenses. All patients have to travel to the District TB Centre to submit sputum samples; the samples are then transferred to the CDST laboratory using a courier system. This was perceived as a major deterrent to regular follow-up because it entailed multiple visits and substantial travel costs. The directly observed therapy (DOT) provider honoraria also remained unpaid for long periods; this substantially demotivates providers from pursuing follow-up examinations. DOT providers also felt that delayed sputum examination and delayed receipt of culture results from the reference laboratory were main reasons for not progressing treatment from the intensive to the continuation phase after completion of the first 6 months of treatment.

TABLE 4.

Provider- and patient-related thematic areas and their perspective on PMDT services

Patient-level barriers to regular follow-up

A total of 12 TB patients were interviewed. The patient interviews revealed that ‘long travel distance’, ‘lack of time due to repeated visits’, ‘poor awareness about the treatment monitoring schedule’ and ‘lack of equipment’ were the main factors leading to poor adherence to follow-up examinations (Table 4). Most patients reported that they were unaware of the treatment monitoring schedule and that they only visited the facility in the event of any ailment. Many patients had to travel long distances (>5 km) to reach the District TB Centre for follow-up examinations and had to bear substantial travel costs. They also reported that it took more than 1 day to reach the facility and undergo the investigations. Some patients also said that a lack of equipment, such as Falcon centrifuge tubes, at the facility were responsible for irregular follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies to examine adherence to follow-up examinations during MDR-TB treatment in the RNTCP. Our study findings reveal that only one in two patients underwent sputum culture examinations, while only one in six underwent serum creatinine examination.

Culture conversion is a useful and appropriate indicator of treatment outcome in patients with MDR-TB.4 It is also crucial for monitoring the bacteriological response to treatment to decide the course of further treatment, i.e., progressing from the intensive to the continuation phase of the treatment regimen, which, if not performed correctly, could lead to the emergence of presumptive XDR-TB cases. Serum creatinine examination is essential for monitoring adverse effects of second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. However, adherence to follow-up sputum and creatinine examinations was poor, as found in this study. This could be one reason why 55% of patients continued on the intensive phase after 6 months of treatment. Weight monitoring during the first 6 months of treatment is also an important predictor of unfavourable outcome.5 Poor adherence to monthly weight measurement, as reported in this study, thus fails to identify poor treatment outcome.

In a qualitative study by Morris et al., MDR-TB patients on treatment expressed a lack of understanding about the disease and the long-term effects of the treatment on their health.6 This might have a significant impact on adherence to follow-up examinations during MDR-TB treatment and adherence to treatment itself. In this study, poor awareness among patients about MDR-TB treatment and management of adverse drug reactions was found to be one of the main reasons for poor adherence to follow-up. Concerted efforts should be directed towards educating the public about the availability of drug-resistant TB services. The involvement of non-governmental organisations to facilitate the transportation of samples to the testing laboratory will certainly improve the proportion and timeliness of sputum testing.

The present study revealed that apart from socio-demographic and clinical parameters, which were found to be non-significant, health system and other patient-level barriers were more frequently associated with poor adherence to follow-up examinations. Patient interviews showed that repeated visits to health facilities not only create a financial burden due to travel and other expenses, they also lead to loss of work and time, which is not compensated. Evidence in the literature suggests that people have to travel long distances to access TB services, incurring considerable direct and indirect costs.7 Previous studies have also shown that poor access to TB services leads to delayed health seeking, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.8,9 Although a courier system is used to transport sputum samples from the District TB Centre to the CDST laboratory, patients have difficulties reaching the District TB Centre to provide the samples; sputum transportation should therefore be decentralised to prevent loss to follow-up. The RNTCP should implement travel reimbursement policy for patients. Supplies of laboratory agents and equipment should be made available on a regular basis at the health facilities to avoid delays in follow-up examinations.

The strength of our study is that it was conducted under routine programme conditions and all data were collected from records and reports maintained by the RNTCP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines have been adhered to in reporting the results.10 Limitations of our study are that the data were collected retrospectively from patient records, which might have been inaccurate or incomplete; however, routine supervision and monitoring within the programme is likely to have reduced this.

To conclude, regular monitoring of drug-resistant TB patients from treatment initiation to treatment completion is key to successful PMDT implementation. The RNTCP’s current need is health systems strengthening and effective community involvement, with the provision of patient friendly follow-up services at the nearest health facilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR, Geneva, Switzerland). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union, Paris, France) and Medécins Sans Frontières (MSF, Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg). The specific SORT IT programme that resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by The Union South-East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi, India; The Centre for Operational Research, The Union, Paris, France; and the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), MSF, Brussels Operational Center, Luxembourg.

The authors thank all study participants and staff of the Uttar Pradesh State Health Directorate for their cooperation.

Funding for the operational research course was made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The contents of this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government, the WHO or The Union.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.6. www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf. Accessed December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Guidelines on programmatic management of drug-resistant TB (PMDT) in India. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2012. http://tbcindia.nic.in/pdfs/guidelines%20for%20pmdt%20in%20india%20-%20may%202012.pdf. Accessed December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtz T H, Sternberg M, Kammerer S et al. Time to sputum culture conversion in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: predictors and relationship to treatment outcome. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:650–659. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gler M T, Guilatco R, Caoili J C, Ershova J, Cegielski P, Johnson J L. Weight gain and response to treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:943–949. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris M D, Quezada L, Bhat P et al. Social, economic, and psychological impacts of MDR-TB treatment in Tijuana, Mexico: a patient’s perspective. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:954–960. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laokri S, Drabo M K, Weil O et al. Patients are paying too much for tuberculosis: a direct cost-burden evaluation in Burkina Faso. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e56752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storla D G, Yimer S, Bjune G A. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathy J P, Srinath S, Naidoo P, Ananthakrishnan R, Bhaskar R. Is physical access an impediment to tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment? A study from a rural district in North India. PHA. 2013;3:235–239. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:867–872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045120. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2636253/?tool=pmcentrez. Accessed December 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]