Abstract

Currently microorganisms are best identified using 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA gene sequencing. However, in recent years matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has emerged as a potential tool for microbial identification and diagnosis. During the MALDI-TOF MS process, microbes are identified using either intact cells or cell extracts. The process is rapid, sensitive, and economical in terms of both labor and costs involved. The technology has been readily imbibed by microbiologists who have reported usage of MALDI-TOF MS for a number of purposes like, microbial identification and strain typing, epidemiological studies, detection of biological warfare agents, detection of water- and food-borne pathogens, detection of antibiotic resistance and detection of blood and urinary tract pathogens etc. The limitation of the technology is that identification of new isolates is possible only if the spectral database contains peptide mass fingerprints of the type strains of specific genera/species/subspecies/strains. This review provides an overview of the status and recent applications of mass spectrometry for microbial identification. It also explores the usefulness of this exciting new technology for diagnosis of diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

Keywords: bacterial identification, fungi, MALDI-TOF MS, peptide mass fingerprint, proteomics, viruses

Introduction

The genomic information within a microbial cell translates into more than 2000 proteins, a substantial number of which can be studied using proteomics (Wasinger et al., 1995). It is estimated that for genomes which contain less than 1000 genes, more than 50% of predicted proteome may be identified from the genome. Similarly 30 and 10% predicted proteome may be identified from genomes which carry ca. 2500 and ca. 4000 genes respectively (Jungblut and Hecker, 2004). Thus, a microbial genome containing 600–7000 predicted genes represents a medium-sized complex system where application of proteomics may provide knowledge of a substantial part of the microbe’s proteome.

Characterization and differentiation of microbial proteome developed and progressed with both gel-based and gel-free protein separation methods. SDS-PAGE of whole cell proteins, coupled with computer assisted analysis was used in a few studies for identification and classification of microorganisms (Vandamme et al., 1996). When performed under standardized conditions, this technique was reported to be quite reproducible. The species identification showed an excellent correlation with DNA–DNA hybridization (Vandamme et al., 1996). However, SDS-PAGE protein profiling did not become popular among microbiologists. This might be attributed to: (i) lack of extensive databases for identification of unknown microorganisms, (ii) requirement of highly standardized conditions which included growth of unknown microorganisms on identical media, standardized electrophoretic conditions, staining procedures, and subsequent pattern analysis, (iii) the technique was not precise enough to differentiate highly similar strains. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) also failed to become popular among microbiologists since it was a laborious, hands-on method, even after ready availability of precast commercially produced gels and improved gel analysis softwares (Cash, 2009). The merits and demerits of other quantitative proteomic approaches have been reviewed elsewhere (Tiwari and Tiwari, 2014).

Analysis of cellular proteome is a method which occupies an intermediary position with respect to the phenotypic–genotypic dichotomy, since the proteins analyzed reflect gene products and metabolic functions. The various methods which have been commonly used for detection of microorganisms in a clinical microbiology set-up, with their respective advantages and disadvantages have been listed in Table 1. The increasing use of DNA fingerprinting methods in the last two decades or so has unequivocally established their applicability and utility for identification and classification of microorganisms. However, automation in proteomics technology, in recent years, has increased its throughput and potential use for a number of microbiological purposes like, strain typing and epidemiological studies, identification of microbes inhabiting a particular ecosystem, detection of biological warfare agents, detection of water- and food-borne pathogens and detection of blood and urinary tract pathogens, detection of antibiotic resistance etc. This review provides an overview of the status and recent applications of mass spectrometry (MS) for microbial identification and explores the usefulness of this technology for diagnosis of diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

Table 1.

Microbial detection methods used in clinical microbiology.

| Detection method | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional; culture on microbiological media and identification by biochemical tests |

|

|

|

| Immunological-based methods |

|

|

|

| Florescent in situ hybridization (FISH) |

|

|

|

| Florescent in situ hybridization (FISH) |

|

|

|

| Molecular based methods |

|

|

|

| DNA sequencing |

|

|

|

| Microarrays |

|

|

|

| Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay |

|

|

|

| Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay |

|

|

|

| Metagenomic assay |

|

|

|

| MALDI-TOF MS |

|

|

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is an analytical technique in which chemical compounds are ionized into charged molecules and ratio of their mass to charge (m/z) is measured. Though MS was discovered in the early 1900s, its scope was limited to the chemical sciences. However, the development of electron spray ionization (ESI) and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) in 1980s increased the applicability of MS to large biological molecules like proteins. In both ESI and MALDI, peptides are converted into ions by either addition or loss of one or more than one protons. Both are based on “soft ionization” methods where ion formation does not lead to a significant loss of sample integrity. MALDI-TOF MS has certain advantages over ESI-MS viz. (i) MALDI-TOF MS produces singly charged ions, thus interpretation of data is easy comparative to ESI-MS, (ii) for analysis by ESI-MS, prior separation by chromatography is required which is not needed for MALDI-TOF MS analysis (Everley et al., 2008). Consequently, the high throughput and speed associated with complete automation has made MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer an obvious choice for proteomics work on large-scale (Ekström et al., 2000).

MALDI – Principle and Methodology

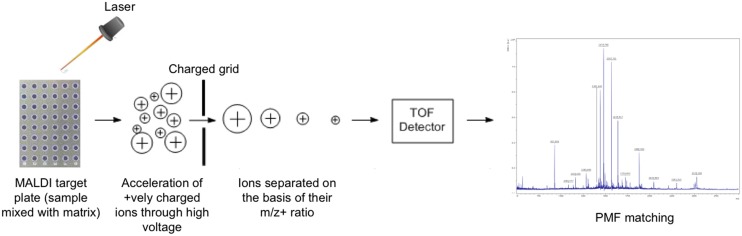

The sample for analysis by MALDI MS is prepared by mixing or coating with solution of an energy-absorbent, organic compound called matrix. When the matrix crystallizes on drying, the sample entrapped within the matrix also co-crystallizes. The sample within the matrix is ionized in an automated mode with a laser beam. Desorption and ionization with the laser beam generates singly protonated ions from analytes in the sample. The protonated ions are then accelerated at a fixed potential, where these separate from each other on the basis of their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). The charged analytes are then detected and measured using different types of mass analyzers like quadrupole mass analyzers, ion trap analyzers, time of flight (TOF) analyzers etc. For microbiological applications mainly TOF mass analyzers are used. During MALDI-TOF analysis, the m/z ratio of an ion is measured by determining the time required for it to travel the length of the flight tube. A few TOF analyzers incorporate an ion mirror at the rear end of the flight tube, which serves to reflect back ions through the flight tube to a detector. Thus, the ion mirror not only increases the length of the flight tube, it also corrects small differences in energy among ions (Yates, 1998). Based on the TOF information, a characteristic spectrum called peptide mass fingerprint (PMF) is generated for analytes in the sample (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram showing the work-flow in a MALDI-TOF MS.

Identification of microbes by MALDI-TOF MS is done by either comparing the PMF of unknown organism with the PMFs contained in the database, or by matching the masses of biomarkers of unknown organism with the proteome database. In PMF matching, the MS spectrum of unknown microbial isolates is compared with the MS spectra of known microbial isolates contained in the database. For species level identification of microbes, a typical mass range m/z of 2–20 kDa is used, which represents mainly ribosomal proteins along with a few housekeeping proteins. The characteristic pattern of highly abundant ribosomal proteins, which represent about 60–70% of the dry weight of a microbial cell, in the mass range of 2–20 kDa (Murray, 2012) is used to identify a particular microorganism by matching its PMF pattern with the PMFs of the ribosomal proteins contained in an extensive open database. Thus, the identity of a microorganism can be established down to the genus, and in many cases to the species and strain level (Fagerquist et al., 2010). This approach is widely used in microbial identification because it is simple and can be conveniently adopted in a microbial diagnostic laboratory, aided by the availability of many commercial libraries of organism PMFs. Microbial identification by matching the biomarker masses with the molecular masses of proteins predicted from the genome sequence is not very popular in microbiological diagnostic laboratories because it requires knowledge of complete genome sequence of an organism before a database of its predicted protein molecular masses could be created.

Although, the culture conditions might profoundly affect the microbial physiology and protein expression profile (Welker, 2011) they do not influence microbial identification by MALDI-TOF MS. Valentine et al. (2005) cultured three bacterial species on four different culture media and found that microbial MALDI-TOF MS identification was independent of culture conditions. Another research group (Carbonnelle et al., 2007) also reported that both the culture conditions and the culture time did not affect microbial identification by MALDI-TOF MS.

A number of organic compounds have been used as matrices for MALDI-TOF MS but for microbiological applications, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA), 2,5-dihydroxy benzoic acid (DHB), and 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (sinapinic acid) have been found to be the most useful. The matrix solution consists of water and a mixture of organic solvents containing ethanol/methanol or acetonitrile and a strong acid like trifluoro acetic acid (TFA), which dissolves the matrix. The solvents penetrate the cell wall of microorganisms and extract out the intracellular proteins. When the solvent evaporates, ‘co-crystallization’ of protein molecules and other cellular compounds entrapped within the matrix solution takes place (Horneffer et al., 2001).

The process of sample preparation for identification of microbes by MALDI-TOF MS depends upon the source from which it was isolated, or on the chemical nature of the constituents of its cell wall. Investigators have evaluated different sample preparation methods for different groups of microorganisms. Some microbes might be identified directly by MS, called direct cell profiling, while for some others whole cell lysates or crude cell extracts are prepared. In direct cell profiling, a single colony of microorganism is picked and spotted directly on to the sample plate and immediately overlaid with the matrix solution. Gram negative bacteria like Neisseria spp. (Ilina et al., 2009), Yersinia spp. (Stephan et al., 2011), and Vibrio spp. (Eddabra et al., 2012) were identified by MALDI-TOF MS using direct cell profiling. A ‘preparatory extraction’ of microbes with formic acid (FA) reportedly increased the ability of MALDI-TOF MS in identifying Gram-positive species. Studies have reported that preparatory extraction was necessary for identification of Gram-positive bacteria by MALDI-TOF MS, but not for Gram-negative bacteria (Alatoom et al., 2011; Saffert et al., 2011). A ‘preparatory extraction’ of microbes with formic acid was also used for sample preparation of sugar-non fermenting bacterial species (Mellmann et al., 2008) and Staphylococcus spp. (Dubois et al., 2010).

Due to the complex nature of their cell walls aerobic actinomycetes, Nocardia and mycobacteria require specialized processing procedures prior to MALDI-TOF analysis. Verroken et al. (2010) described a modified procedure for identification of Nocardia spp. by MALDI-TOF MS. Bacteria were lysed in boiling water, followed by ethanol precipitation of proteins. The precipitated proteins were dried, resuspended in 70% formic acid and acetonitrile and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Researchers have reported different methods for sample preparation for identification of mycobacteria by MALDI-TOF MS, ranging from direct bacterial profiling to treatment with formic acid, safety being a major concern for routine investigations. EI Khéchine et al. (2011) described a procedure which combined inactivation and processing methods. Mycobacterial colonies collected in screw-cap tubes containing water and 0.5% Tween 20 were inactivated by heating at 95°C for 1 h. Inactivated samples were centrifuged and vortexed with glass beads to disrupt the mycobacterial cell wall, the resultant pellet was re suspended in formic acid, acetonitrile, and centrifuged again. Finally, the supernatant was deposited onto the MALDI target plate and overlaid with matrix.

As in bacteria, various sample processing methods have been investigated for identification of yeasts by MALDI-TOF MS, out of which ‘preparatory extraction’ with formic acid was reported to be most suitable (Stevenson et al., 2010b; Theel et al., 2012). Cassagne et al. (2014) evaluated five methods for sample preparation for fungal hyphae and spores. They finally devised a protocol wherein fungi were cultivated on Sabouraud gentamicin-chloramphenicol agar for 72 h at 27°C, extracted with formic acid following incubation in ethanol. Acetonitrile was added, the mixture was centrifuged and supernatant was used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Lau et al. (2013) reported a method based on mechanical lysis for sample preparation of fungal hyphae and spores. A small specimen from the mold isolate was suspended in ethanol and zirconia-silica beads, vortexed and centrifuged. The pellet was re suspended in 70% FA, vortexed again, and centrifuged. The supernatant was used for subsequent analysis by MALDI-TOF MS. Both methods reportedly gave good results in their respective studies. Analysis of intact cells of members of the genus Penicillium generated poor MALDI spectra, but re suspension of the conidia and spores in trifluoroacetic acid-acetonitrile and disruption with glass beads discriminated the species with 100% accuracy (Hettick et al., 2008a).

The discovery of suitable matrices, usage of whole/intact cells for recording PMF of microbes in the typical mass range (m/z) of 2–20 kDa, followed by availability of dedicated databases for microbial identification has made MALDI-TOF MS a lucrative alternative for microbial identification. The first MALDI-TOF MS system capable of microbial identification, termed “MALDI Biotyper” was developed by Bruker Daltonics. The MALDI Biotyper consisted of a basic MALDI-TOF platform, operating and analysis softwares, an onsite database and a simple method for extraction/preparation of sample (Seng et al., 2009). The software and database integrated easily with the Bruker MALDI-TOF instrument and its associated operating and analysis softwares. This system also allowed for up gradation by providing option of adding internal libraries of organisms. Another MALDI platform for microbial identification was introduced by Shimadzu in collaboration with bioMérieux. Shimadzu supplied the instrumentation and the analysis software “Launchpad,” while bioMérieux supplied and maintained the centralized database, “SARAMIS” which could be constantly updated. Later, Andromas introduced a different kind of database and software for routine bacteriological identification which was compatible with both Bruker and Shimadzu instruments (Emonet et al., 2010). The greatest break-through in the development of MALDI-TOF MS came with its regulatory approval for routine identification of bacteria and fungi in clinical microbiological laboratories. In the last 2 years, MALDI Biotyper CA System (Bruker Daltonics Inc.) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for identification of cultured bacteria from human specimens (in vitro diagnosis). Similarly, VITEK® MS (bioMerieux Inc.) was approved by the US FDA for identification of cultured bacteria and yeasts (Patel, 2015). The list of microorganisms approved for identification is unique to the individual system (Patel, 2015). MALDI-TOF MS was first approved for clinical use in China in 2012 when bioMérieux VITEK MS system was approved by China State FDA for in vitro diagnostic (IVD) purposes (Luo et al., 2015). Later, China State FDA also approved the Bruker IVD MALDI Biotyper System for routine identification of microorganisms isolated from human specimens.

The organism databases are the key components of commercial MALDI platforms. They are continually increasing in size and are regularly updated by the manufacturers with discovery of new microbial species and annotations. Both, the Bruker and the Shimadzu systems contained a large collection of representative organisms in their databases and yielded comparable results with very low false positive rates (Carbonnelle et al., 2012). With a few exceptions, isolates were rarely misidentified by these devices. In a few MALDI-based identification studies, some organisms could not be identified; this failure was attributed to the organism not being included in the earlier databases rather than to the methodological error (Carbonnelle et al., 2012). A critical drawback of the proprietary softwares and databases is their limited accessibility to the private researchers due to their high costs. Nevertheless, a few research groups have developed some open-source softwares and databases which are freely available for the scientific community. To name a few, these are, mMASS, Mass-Up, pkDACLASS, MALDIquant, SpectraBank, BIOSPEAN, etc. (Strohalm et al., 2008; Ndukum et al., 2011; Böhme et al., 2012; Gibb and Strimmer, 2012; Raus and Šebela, 2013).

Applications in Microbial Diagnosis

MALDI-TOF MS in Bacteriology

Clinical Bacteriology

Conventionally diagnosis of bacterial infections in the body fluids is carried out on the basis of biochemical and metabolic-profiling that requires 24–48 h for identification of the inflicting bacterial species. In the meantime, patients are administered empirical antibiotics, which are sometimes inappropriate. Clinical microbiology laboratories require rapid, reliable, and cost effective methods for identification of potential pathogens in clinical samples so that appropriate antimicrobial therapy may be initiated early. A number of researchers have shown that MALDI-TOF MS can be used for early identification of bacteria in blood cultures, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cerebrospinal fluids, respiratory tract infections, stool samples etc.

Many studies have shown that MALDI-TOF MS equalled or even surpassed the conventional diagnostic methods in speed and accuracy in detecting blood stream infections (La Scola and Raoult, 2009; Stevenson et al., 2010a; Foster, 2013; Haigh et al., 2013; Tadros and Petrich, 2013). A few studies suggested that additional pre-treatment of body fluids by ammonium chloride (Prod’hom et al., 2010), formic acid (Christner et al., 2010), or short-term incubation on solid medium (Idelevich et al., 2014) further improved the diagnostic potential of MALDI-TOF MS.

When conventional methods for identification of urinary tract pathogens for diagnosis of UTIs were compared with MALDI-TOF MS based identification systems, it was found that MALDI-TOF MS required minimal processing time and identified bacteria from urine samples in the presence of even more than two uropathogens (Ferreira et al., 2010; Köhling et al., 2012; Burillo et al., 2014). A few researchers have suggested procedures involving differential centrifugation of urine samples (Rosselló et al., 2014) or diafiltration (Demarco and Burnham, 2014) to further improve the clinical sensitivity and turnaround time of MALDI-TOF MS based diagnosis of UTI.

Diagnosis of infectious diarrhea in laboratory is usually done by culture and identification of bacteria in the stool samples. This is a costly and time consuming process requiring 3–5 days for detection and identification of enteric bacterial pathogens. He et al. (2010) performed a comparative study of identification by MALDI-TOF MS versus routine phenotypic methods for identification of suspicious colonies from stool samples. They found that the entire procedure for identification by MALDI-TOF MS, from smear preparation to reporting of the final result was completed within 30 min, thus shortening the turnaround time of the test by 2–3 days.

Bacterial meningitis is a neurological emergency. Early diagnosis is vital for rapid initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. MALDI-TOF MS has been used for direct detection of bacteria causing meningitis in cerebrospinal fluids (Segawa et al., 2014). It has also been used for rapid identification of atypical, Gram-negative environmental organisms and respiratory tract pathogens which chronically infect patients with cystic fibrosis (Alby et al., 2013; Baillie et al., 2013). Recently, a very novel application of MALDI-TOF MS was shown by Guembe et al. (2014) who reported that MALDI-TOF MS can perform better than conventional culture methods in diagnosis of catheter-related bloodstream infections.

Food- and Water-Borne Bacteria

Rapid identification of pathogenic microorganisms is important to ensure safety and quality of water and food products. MALDI-TOF MS has been shown to be useful for early detection of bacterial hazards which might contaminate drinking water. The genus Aeromonas which is indigenous to surface waters is currently composed of 17 species, of which seven can cause severe water-borne outbreaks. Donohue et al. (2007) used the m/z signature of known strains of Aeromonas to assign species to unknown environmental isolates. Their results showed that MALDI-TOF MS rapidly and accurately classified unknown species of the genus Aeromonas, which was suitable for environmental monitoring.

MALDI-TOF MS has also been applied successfully in food microbiology for various purposes like, identification and classification of lactic acid bacteria in fermented food (Nguyen et al., 2013), detection of bacteria involved in spoilage of milk and pork (Nicolaou et al., 2012), identification of bacteria isolated from milk of dairy cows (Barreiro et al., 2010), identification of bacteria present in probiotics and yogurt (Angelakis et al., 2011), identification of pathogenic bacteria contaminating powdered infant formula-food (Stephan et al., 2010), characterization of biogenic amine-producing bacteria responsible for food poisoning (Fernández-No et al., 2010) and for identification of causative agents of seafood-borne bacterial gastroenteritis (Hazen et al., 2009; Böhme et al., 2010, 2011).

Environmental Bacteriology

Tests based on biochemical traits usually fail to identify microbes isolated from environmental samples, as the diversity of microbes in these habitats is enormous (Torsvik et al., 2002). Various studies have shown that whole cell MALDI-TOF MS can be used as an efficient tool to identify and characterize isolates which originate from specific ecosystems. Researchers have reported the use of MALDI-TOF MS in identification of microbes isolated from sewage sludge (Ruelle et al., 2004), for grouping of bacteria isolated from marine sponges into different proteotaxanomic groups (Dieckmann et al., 2005) and for identifying bacteria inhabiting soil contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl (Uhlik et al., 2011).

Another research group performed MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the cultivable fraction of environmental samples. They acquired strain-specific spectra which helped in grouping aerobic and moderately halophilic prokaryotes into phenotypic clusters belonging to distinct taxa. They suggested that, if the culture conditions were not radically different, irrespective of the age or quality of the culture, MS spectrum of a microbe reflects its taxon-specific phenotypic properties which results in guaranteed identification (Munoz et al., 2011).

In another study MALDI-TOF MS was used for differentiating bacterial species of the family Rhizobiaceae. Subdivided within three genera, these bacterial species establish either symbiotic or saprophytic interactions with plants.The research group even constructed a database that included the type strains of currently accepted species in the family and validated it by identifying all rhizobial strains isolated from nodules and tumors (Ferreira et al., 2011).

Detection and Identification of Agents of Biological Warfare

Fast and reliable identification of microbes which pose threats as agents of bioterrorism is required, not only to combat biological-warfare attacks, but also to prevent natural outbreaks caused by these organisms. Conventionally, organisms which pose severe threats as agents of bioterrorism have been identified by phenotypic, genotypic, and immunological identification systems which are slow, cumbersome and pose significant risk to the laboratory personnel. Recently various researchers reported MALDI-TOF MS as a simple, rapid and reliable approach to identify highly pathogenic organisms like Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetti, Bacillus anthracis, Francisella tularensis, and Y. pestis (Shaw et al., 2004; Pierce et al., 2007; Lasch et al., 2009; Ayyadurai et al., 2010; Seibold et al., 2010; Lista et al., 2011; Vranakis et al., 2013).

Further work is being carried out to develop safe and MS-compatible protocols for inactivation of vegetative cells and spores of highly pathogenic organisms, which can be integrated into a routine microbiological laboratory. Lasch et al. (2008) proposed a tri-fluoro acetic acid (TFA) based inactivation protocol for vegetative cells and spores of pathogenic organisms, but Couderc et al. (2012) found that for Yersinia isolates, ethanol inactivation yielded MALDI-TOF MS spectra of significantly higher quality than TFA inactivation. Jeong et al. (2014) reported a direct in situ MALDI-TOF MS which allowed a high-throughput detection and identification of aerosolized Bacillus spores, without any pretreatment process. The spores of the Bacillus spp. were directly spotted on the MALDI target plate and left for air-drying. These were subsequently coated with the matrix solution. After the matrix solution air-dried, the spotted samples were analyzed by MS (Jeong et al., 2013, 2014).

MALDI-TOF MS has also been shown to be useful for detection of protein toxins, such as staphylococcal enterotoxin B, botulinum neurotoxins, Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin, shiga toxin etc. which can be used as potential agents for bioterrorism when delivered via an aerosol route (Kull et al., 2010; Alam et al., 2012). In a biological war, early and unambiguous detection of toxins from aerosols is required to initiate medical countermeasures. Alam et al. (2012) developed a simple method of sample processing for identification of protein toxins by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS method. Nebulizer was used to generate aerosols which were collected using a cyclone collector. Tandem MS data with information from peptide sequences was used for detecting toxins that originated from organisms of any geographical location.

Detection of Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria

MALDI-TOF MS has been shown to generate PMFs capable of discriminating lineages of methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (Wolters et al., 2011). Under careful experimental conditions, it has also been shown useful for subtyping methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (Croxatto et al., 2012). Similarly, MALDI-TOF MS has been shown to be of great use in identifying vancomycin-resistant enterococci (Griffin et al., 2012; Nakano et al., 2014). Wang et al. (2014) suggested that MALDI-TOF MS could be used as a screening tool for discriminating vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains from vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium strains.

The most common mode of microbial resistance to β-lactams, the largest class of antibiotics, is their enzymatic hydrolysis by β-lactamases. The production of β-lactamases is detected by MALDI-TOF MS employing a ‘mass spectrometric β-lactamase (MSBL) assay.’ In this assay, buffered solution of the antibiotic is mixed with bacterial culture and incubated. The reaction mixture is centrifuged and supernatant subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis. The β-lactamase producers inactivate the β-lactam ring of the antibiotic by addition of a residue of water. The mass shift in the non-hydrolyzed and the hydrolyzed forms of the antibiotic confirms the presence or absence of β-lactamase producing bacteria. The MSBL assay has been applied for detection of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics like penicillin, ampicillin, piperacillin, cetazidime, cefotaxime, ertapenem, meropenem, and imipenem. Using MSBL assay researchers have successfully detected β-lactamase producing organisms like Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumanni, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloaceae, Salmonalla spp. etc. (Hrabák et al., 2011; Hooff et al., 2012; Sparbier et al., 2012a; Kostrzewa et al., 2013). Given the accuracy of resistance detection with MSBLs, further innovations and improvements in terms of enhancing speed of resistance detection and expanding detection of resistance for newer classes of β-lactam antibiotics in MSBL assays are being envisaged. Recently, Johansson et al. (2014) developed a MALDI-TOF MS method for detection and verification of carbapenemase production in anaerobic bacterium, Bacteroides fragilis as early as 2.5 h. Hoyos-Mallecot et al. (2014) evaluated a MALDI-TOF MS method for identification and differentiation of carbapenemase producing clinical strains of Enterobacteriaceae and P. aeruginosa from metallo-β-lactamase producing strains. Hart et al. (2015) reported a modified strategy for detection of biomarkers of antibiotic resistance in clinical strains of E. coli using MALDI-TOF MS. They suggested that instead of using intact bacterial cells for MS, the periplasmic compartment should be extracted (since β-lactamases are located in the periplasm); in-solution digested with trypsin, separated by nano-LC before MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Using this approach they reported the peptide sequence of biomarkers for several classes of β-lactamases like CTX-M-1 group extended spectrum β-lactamase, TEM β-lactamase, VIM a metallo-β-lactamase and CMY-2 an ampC β-lactamase. Moreover using this approach they also detected the peptides specific to an aminoglycoside modifying enzyme Kan-R.

Similar to β-lactams, resistance in microorganisms to aminoglycosides is mainly due to the enzymatic modification of antibiotics by bacterial acyltransferases, adenyltransferases, and phosphotransferases. Since these enzymes show different preferentiality for the CoA substrate present in different aminoglycosides, it has not been possible to establish a universal MS-based assay for detection of aminoglycoside resistance. Further efforts to develop and standardize MALDI-TOF MS for detection of aminoglycoside resistance in routine laboratory are still underway.

Bacterial Strain Typing and Taxonomy

Conventional classification of bacteria has been carried out on the basis of biochemical, metabolic and antigenic properties. However, currently microbial species are being identified primarily on the basis of genomic information. The sequencing of 16S rDNA is considered to be the ‘gold standard,’ because it is present in every prokaryote and allows reconstruction of a global phylogeny (Woese et al., 1990; Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994; Pace, 1997). Most DNA fingerprinting methods, however, do not correlate phylogenetically and fail to give any information regarding the evolutionary relationship between various species. Genomic techniques like amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) are used for subtyping of bacteria for epidemiological purposes. Though 16S rDNA sequencing is adequate to assign genus or species to an isolate, in most cases it is not sufficient for refined typing, e.g., epidemiological studies. PFGE, can be applied for high resolution typing, but is generally inappropriate for assigning genus or species to microorganisms (O’Leary et al., 2011).

Proteomics represents the functional aspect of genomics and can be used as a taxonomic tool. Gel-based whole cell protein profiling may be as cumbersome and time consuming as any other genomic technique. On the other hand MALDI-TOF MS intact cell or whole cell PMF based typing is a rapid and sensitive method for bacterial identification. In many cases it has shown resolution and reproducibility which is better than gel-based protein or DNA fingerprinting techniques (van Baar, 2000; Fenselau and Demirev, 2001; Lay, 2001).

Numerous studies have shown that MALDI-TOF MS is a rapid, reliable and cost-effective technique for identification of bacteria. The method, however, has some lacunae: (i) proper identification of organisms is possible only when the spectral database contains information about specific genes like prokaryotic 16S rRNA, gyrB, rpoB, or hsp60 of strains/species of a particular genus, (ii) databases should be prepared locally for certain taxa (e.g., Streptococcus or Staphylococcus) in which geographical variations lead to variations in the genotype and phenotype (Benagli et al., 2011).

During the past few years various researchers have shown applicability of MS for bacterial identification, taxonomy and strain typing. Haag et al. (1998) used MALDI-TOF MS for rapid characterization of pathogenic Haemophilus strains. They also determined strain-specific differences among H. influenzae isolates from several patients. Nilsson (1999), detected strain-specific biomarkers based on the analysis of six different strains of Helicobacter pylori. Lundquist et al. (2005) showed differentiation of four subspecies of F. tularensis using this approach. Carbonnelle et al. (2007) showed that MALDI-TOF MS was a powerful tool for the identification of clinical isolates of coagulase negative staphylococci. MALDI-TOF MS was used for rapid identification of ten different species of S. viridans (Friedrichs et al., 2007). When the results of species identification obtained by MALDI-TOF MS were compared with the phenotypic/genotypic identification systems, a 100% consonance was achieved. Similarly, a variety of Staphylococcus spp., pathogenic Neisseria spp., clinically important Yeast species and Mycobacterium spp. were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (Ilina et al., 2009; Dubois et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2010b; Saleeb et al., 2011). Table 2 lists microorganisms in which intact cell (direct bacterial profiling) was used for bacterial identification and strain typing.

Table 2.

Bacteria in which MALDI-TOF MS was used for identification and strain typing.

MALDI-TOF MS is not only used for species identification but has application in strain typing also. Kumar et al. (2004) showed that MALDI-TOF MS may be a useful tool for discriminating strains of beta hemolytic streptococci, and also for characterization of untypable strains of streptococci group A. Eddabra et al. (2012) used MALDI-TOF MS to discriminate 30 environmental strains of Vibrio spp. Stephan et al. (2011) used MALDI-TOF MS for rapid identification of Y. enterocolitica strains to the species, and subtyping to the biotype level. MALDI-TOF MS based methods for the discrimination and typing of mycobacteria, typing multidrug-resistant K. pneumonia, and typing strains responsible for nosocomial outbreak of A. baumannii have been described (Shitikov et al., 2012; Berrazeg et al., 2013; Mencacci et al., 2013).

MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of an individual microbe is the taxon-specific property of that organism, which is independent of its geographical location, culture conditions (which should not be drastically different) or sample preparation methodology. With this approach, not only identification of new isolates as members of existing species is possible if their type strains have been previously studied (Ruelle et al., 2004), recognition of coherent phenotypic patterns reflecting taxonomic identities is also possible. The ease and rapidity in identification of large numbers of isolates can be used to study taxonomic and inter- and intra-specific diversity (Feli and Dellaglio, 2007).

MALDI-TOF MS in Virology

Clinical Virology

Viruses were traditionally detected by cell culture, which in spite of being the gold standard, often took days or even weeks before any results were available. It was later replaced or complemented by lesser sensitive immunological methods, based on antibody analysis (by immunoassays or immunofluorescence) and by more sensitive molecular methods based on PCR and dot blot hybridization. The use of MALDI-TOF MS in virology has advanced less as it has in bacteriology or mycology. This might be a consequence of the relatively low protein content of viruses (Kliem and Sauer, 2012), higher molecular weight of viral proteins (>20,000 Da) and a probable carryover of debris of the cell substrate in which viruses are cultured in vitro. Nevertheless, many researchers have proved the utility of MALDI-TOF MS for diagnosis of various infectious viruses in clinical samples like influenza viruses, enteroviruses, human papilloma viruses (HPVs), herpes virus, hepatitis virus etc. (Sjöholm et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2011; Piao et al., 2012). Interestingly in most of the studies, the viral genetic material was amplified by PCR and the amplicons were analyzed/identified by MALDI. Sjöholm et al. (2008) developed an efficient MALDI-TOF MS based screening method for multiplex detection of all human herpes viruses which were present in different archival biological samples. The sensitivity and the detection limit of viruses by MALDI-TOF MS method was high and comparable to reference methods like oligonucleotide microarrays and multiplex PCR (Sjöholm et al., 2008).

Yi et al. (2011) reported the use of a PCR-based MS method for detection of high-risk HPVs, a prime cause of human cervical cancer. They claimed that the high-throughput and cost-effectiveness associated with the method made it suitable for diagnosis in routine clinical settings and for epidemiological studies. Piao et al. (2012) combined the multiplex PCR with MALDI-TOF MS and developed a PCR-Mass assay which simultaneously detected eight distinct viruses associated with enteric infections in humans. Later, Peng et al. (2013) proved the utility of multiplexed MALDI-TOF for type-specific detection of human enteroviruses associated with hand, foot and mouth diseases. Recently, Calderaro et al. (2014) reported that MALDI-TOF MS was an effective, rapid and inexpensive tool which identified various poliovirus serotypes from different clinical samples. They further reported that through MALDI-TOF MS, specific viral biomarkers could be detected which were helpful in differentiating virus-infected cells from healthy cells.

Viral Genotyping, Subtyping, and Epidemiological Studies

Apart from viral identification, MALDI-TOF MS has also been used in virology for genotyping of JC polyomaviruses (Bayliss et al., 2010), hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses (Ilina et al., 2005; Ganova-Raeva et al., 2010) and for detection of mutations in hepatitis B viruses (Luan et al., 2009). Also, many researchers have demonstrated the application of MALDI-TOF MS for screening of influenza virus subtypes and for tracking epidemiology of influenza viruses (Schwahn et al., 2009, 2010; Fernandes and Downard, 2014). Newer strains of influenza viruses frequently originate by mixing of genetic material of several strains in a common host. Thus, detection of ever evolving influenza viruses is a challenge for PCR based molecular methods, because the primers fail to anneal to their respective target sequences and need to be redesigned repeatedly. Similarly, the antibody-based immunological assays fail to identify the antigenically distinct, reassorted virus strains. Rapid identification and characterization of the inflicting influenza viral strains is necessary to initiate an early, effective therapy and to prevent a probable pandemic. MALDI-TOF MS has emerged as a rapid and reliable approach to screen highly evolving influenza virus types and subtypes. Chou et al. (2011) reported the use of MALDI-TOF MS in combination with antibody-magnetic nanoparticles for detection and rapid screening of influenza virus subtypes. Later, Downard (2013) described a method for detection of strains of influenza viruses using whole virus protein digests. This ‘proteotyping approach’ was successful in typing, subtyping, and tracing the lineage of human influenza viruses. He even described the success of his ‘proteotyping approach’ in characterization of strains of parainfluenza virus, another respiratory infectious agent.

Detection of Antiviral Resistance

The studies in this area are scanty. However, MALDI-TOF MS has proved efficacy in detecting drug resistance to ganciclovir in cytomegaloviruses which frequently infect transplant recipients (Zürcher et al., 2012).

MALDI-TOF MS in Mycology

Clinical Mycology

Conventional methods for identification of fungi are based on morphological, biochemical, and/or immunological properties which might span 2–5 days, or more, and often require combining several phenotypic methods for conclusive interpretations. The molecular methods based on analysis of genes encoding 18S rRNA and the internal transcribed spacer regions 1 and/or 2 (ITS 1/2) are tedious and time consuming (Sendid et al., 2013). Rapid and accurate identification of the inflicting fungal species is required for early initiation of antifungal therapy.

Fungal identification by MALDI-TOF MS in the medical mycology laboratory has moved at a slower pace than bacterial identification, owing to their inherent biological complexity which makes their study as a whole difficult, and also due to co-existence of different fungal phenotypes (hyphae and/or conidia) in the same organism (Santos et al., 2010). In order to obtain reproducible PMF results, parameters like culture media, quantity/type of colony material and incubation time, need to be carefully standardized. Also, the fungal cells might require additional treatment with trifluoroacetic acid, formic acid, or acetonitrile along with beating with beads to disrupt strong cell walls.

The first study describing the use of MALDI-TOF MS for identification and characterization of single-celled fungus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae was reported in Amiri-Eliasi and Fenselau (2001). Among fungi, highly reproducible PMF spectra have been reported for the ascomycetous and basidiomycetous yeasts including organisms like Candida, Cryptococcus, and Pichia. These genera of yeast form uniform colonies on agar plates which can be lysed efficiently with the standard procedure (as used in bacteria) for MALDI-TOF sample preparation (Bader, 2013). However, Cassagne et al. (2014) evaluated various pretreatment procedures for MALDI-TOF MS identification of yeasts and reported that although labor-intensive, complete extraction with formic acid/acetonitrile yields better identification results. Various researchers have reported that MALDI-TOF MS was a reliable and time-saving approach for identification of various yeast species in bloodstream infections (Spanu et al., 2012; Yaman et al., 2012; Lavergne et al., 2013). Several researchers have described the use of MALDI-TOF MS for detection of various human fungal pathogens. These have been summarized in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Fungi which have been identified using MALDI-TOF MS.

| Organisms | Reference |

|---|---|

| Fusarium spp. | Dong et al. (2009), Kemptner et al. (2009) |

| Aspergillus spp. | Li et al. (2000), Hettick et al. (2008b), Alanio et al. (2011), Pan et al. (2011) |

| Penicillium spp. | Chen and Chen (2005) |

| Fusarium proliferatum | Seyfarth et al. (2008) |

| Lichtheimia spp. | Schröd et al. (2012) |

| Dermatophyte species | Erhard et al. (2008), Theel et al. (2011), Nenoff et al. (2013) |

| Cryptococcus neoformans, C. gattii | Mc Taggart et al. (2011) |

| Neoscytalidium spp. | Alshawa et al. (2012) |

| Candida spp. | Spanu et al. (2012) |

Detection of Antibiotic Resistance in Fungi

Identification/prediction of resistance for antifungals by MALDI-TOF MS has not advanced as much asSit has, in predicting resistance in bacteria. This might be attributed to the fact that antimycotic resistance in fungi is not as frequent as in bacteria due to absence of drug degrading enzymes. Only a few fungal species like C. glabrata or C. krusei and C. parapsilosisis have been reported to be intrinsically resistant to azoles and echinocandins respectively (Bader, 2013). Similarly, a species-specific resistance to antimycotic agents is observed in many molds and zygomycetes (Pfaller et al., 2002; Alastruey-Izquierdo et al., 2010). Thus, drug resistance in fungal isolates may be predicted simply by identification of the inflicting fungal species by MALDI-TOF MS (Bader, 2013).

Fungal Strain Typing and Taxonomy

The use of MALDI-TOF MS for strain typing of fungal isolates is still in infancy and not as successful as in bacteria. In contrast to yeasts, it has been difficult to type molds since they have complicated phylogenetic relationships (Samson and Varga, 2009) and more complicated morphology. Strain typing by MALDI-TOF MS was, however, reported to be feasible with C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (Qian et al., 2008; Pulcrano et al., 2012).

Future Perspectives

Although attempts for MS based bacterial identification and diagnosis date back to mid 1970s it is only in the recent years that microbiologists have realized the potential and applicability of MALDI-TOF MS in routine microbiological laboratories. The current gold standard for microbial identification – 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA gene sequencing is not favorable in terms of both cost and time. Bizzini et al. (2011) claimed that including the cost of consumables, salaries, and apparatus-depreciation, identification of a single bacterial isolate by 16S rRNA sequencing costed approximately 100 US dollars in their laboratory and the results were available after 48 h. On the other hand identification of a single bacterial isolate by MALDI-TOF MS could be done in minutes and costed only a few US dollars (Seng et al., 2009; Cherkaoui et al., 2010).

Comparison of PMF of unknown isolate to reference mass fingerprints present in the database is the most crucial step for species identification which requires a database containing not only reference mass fingerprints of all species of interest, but also mass fingerprints of multiple strains of each species (Lartigue et al., 2009). The MALDI-TOF MS technology failed to distinguish E. coli and Shigella spp. (Bizzini et al., 2010) or discriminate among species of the mitis complex of Streptococci (Seng et al., 2009; van Veen et al., 2010). The former failure has been explained by the fact that E. coli and Shigella were one species phylogenetically but due to historical and clinical constraints microbiologists have classified them into two species. The reason for improper delineation of S. pneumoniae and S. mitis is the close relationship between the two species (a microbiological constraint) which cannot be distinguished by any database update, except tests like optochin sensitivity or bile solubility (Kilian et al., 2008). Such constraints of MALDI-TOF MS certainly need to be addressed in future.

The major constraint against using MALDI-TOF MS in routine microbiological diagnosis is the reproducibility of the PMFs of the same microbial species during different experiments in the same laboratory or during different experiments in different laboratories employing the same/different MALDI-TOF equipment. The intra-laboratory reproducibility studies have shown a higher level of concordance in PMFs during repeated experiments with the same MS equipment using similar sample preparation technique (Walker et al., 2002). Another study reported that intra-laboratory reproducibility of PMFs depended only on the quality of the microbial samples and was independent of the sample preparation technique (Croxatto et al., 2012). However, studies on reproducibility of PMFs during inter-laboratory studies have yielded conflicting results. Two independent research studies showed a higher level of reproducibility in PMFs of identical microorganisms identified in separate laboratories employing similar sample preparation technique, the same MS equipment and the same analysis software (Wang et al., 1998; Walker et al., 2002). On the other hand, another study reported poor inter-laboratory concordance during MALDI-TOF analysis of identical aliquots of E. coli by three separate laboratories using similar sample preparation techniques, but different commercial MALDI-TOF equipment (Wunschel et al., 2005). This research group further combined the PMF spectra of individual laboratories and formed a ‘multiple laboratory master PMF.’ When this multiple laboratories’ master PMF spectra were used to identify E. coli, 100 percent identification was observed in each laboratory (Wunschel et al., 2005). Thus, this study provided a solution to a very important question that is, the potential of MALDI-TOF MS for microbial identification in different geographical locations with different MALDI-TOF equipment. By employing a standard protocol for MALDI-TOF MS analysis and creating a library/database containing PMFs from multiple laboratories (with different MALDI-TOF equipment), this constraint could be overcome easily.

In recent years there has been a plethora of information about MALDI-TOF MS and its application to a broad spectrum of microbes ranging from Gram positive to Gram negative bacteria, from clinical samples to extreme halophiles and from BSL-3 organisms to environmental isolates. Beyond the realms of microbial world, recent studies indicate that MALDI-TOF MS can even be applied to identify algae (von Bergen et al., 2009), mosquitoes (Yssouf et al., 2014), nematodes (Perera et al., 2005), and insects (Feltens et al., 2010; Hoppenheit et al., 2013). Independence of the culture conditions, culture formulations, cultivation time, quantity of inoculum required for identification, have made MALDI-TOF MS as the technique of choice in routine microbiological laboratories. The provision for integrating in-built databases in the public databases of MALDI-TOF MS, as well as development of inexpensive and user-friendly softwares for comparisons and analyses would further increase the credibility of MALDI-TOF MS in future. What seemed an exaggeration sometimes back has now become a reality. MALDI-TOF MS has become a valuable tool for a microbiological laboratory, which might potentially replace molecular identification techniques in near future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

NS is supported by Start up Research Grant, Young Scientists, Science and Engineering Research Board of Department of Science and Technology. PK is supported by UGC-Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship. Financial assistance received from Indian Council of Medical Research grant (Grant no. AMR/17/2011-ECD-1), DU-DST-PURSE grant, the UGC-Special Assistance Programme (DRS-I) and University R & D research grant to the Department of Microbiology, University of Delhi South Campus is also duly acknowledged.

References

- Alam S. I., Kumar B., Kamboj D. V. (2012). Multiplex detection of protein toxins using MALDI-TOF-TOF tandem mass spectrometry: application in unambiguous toxin detection from bioaerosol. Anal. Chem. 84 10500–10507. 10.1021/ac3028678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanio A., Beretti J. L., Dauphin B., Mellado E., Quesne G., Lacroix C., et al. (2011). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for fast and accurate identification of clinically relevant Aspergillus species. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17 750–755. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Cuesta I., Walther G., Cuenca-Estrella M., Rodriguez-Tudela J. L. (2010). Antifungal susceptibility profile of human-pathogenic species of Lichtheimia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 3058–3060. 10.1128/AAC.01270-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatoom A. A., Cazanave C. J., Cunningham S. A., Ihde S. M., Patel R. (2012). Identification of non-diphtheriae Corynebacterium by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50 160–163. 10.1128/JCM.05889-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatoom A. A., Cunningham S. A., Ihde S. M., Mandrekar J., Patel R. (2011). Comparison of direct colony method versus extraction method for identification of Gram-Positive cocci by use of bruker biotyper matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 2868–2873. 10.1128/JCM.00506-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alby K., Gilligan P. H., Miller M. B. (2013). Comparison of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (maldi-tof) mass spectrometry platforms for the identification of gram-negative rods from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 3852–3854. 10.1128/JCM.01618-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alispahic M., Christensen H., Hess C., Razzazi-Fazeli E., Bisgaard M., Hess M. (2011). Identification of Gallibacterium species by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry evaluated by multilocus sequence analysis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301 513–522. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshawa K., Beretti J. L., Lacroix C., Feuilhade M., Dauphin B., Quesne G., et al. (2012). Identification of clinical dermatophyte and Neoscytalidium species by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50 2277–2281. 10.1128/JCM.06634-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A., Culebras E., Picazo J. J. (2012). Identification of Acinetobacter species: is Bruker biotyper MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry a good alternative to molecular techniques? Infect. Genet. Evol. 12 345–349. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri-Eliasi B., Fenselau C. (2001). Characterization of protein biomarkers desorbed by MALDI from whole fungal cells. Anal. Chem. 73 5228–5231. 10.1021/ac010651t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis E., Million M., Henry M., Raoult D. (2011). Rapid and accurate bacterial identification in probiotics and yoghurts by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J. Food Sci. 76 M568–M571. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadurai S., Flaudrops C., Raoult D., Drancourt M. (2010). Rapid identification and typing of Yersinia pestis and other Yersinia species by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. BMC Microbiol. 10:285 10.1186/1471-2180-10-285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader O. (2013). MALDI-TOF-MS-based species identification and typing approaches in medical mycology. Proteomics 13 788–799. 10.1002/pmic.201200468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie S., Ireland K., Warwick S., Wareham D., Wilks M. (2013). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation-time of flight mass spectrometry: rapid identification of bacteria isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 70 144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro J. R., Ferreira C. R., Sanvido G. B., Kostrzewa M., Maier T., Wegemann B., et al. (2010). Identification of subclinical cow mastitis pathogens in milk by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Dairy Sci. 93 5661–5667. 10.3168/jds.2010-3614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss J., Moser R., Bowden S., McLean C. A. (2010). Characterisation of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the genome of JC polyomavirus using MALDI TOF mass spectrometry. J. Virol. Methods 164 63–67. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benagli C., Rossi V., Dolina M., Tonolla M., Petrini O. (2011). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for the identification of clinically relevant bacteria. PLoS ONE 6:e16424 10.1371/journal.pone.0016424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrazeg M., Diene S. M., Drissi M., Kempf M., Richet H., Landraud L., et al. (2013). Biotyping of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates from France and Algeria using MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS ONE 8:e61428 10.1371/journal.pone.0016428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzini A., Durussel C., Bille J., Greub G., Prod’hom G. (2010). Performance of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of bacterial strains routinely isolated in a clinical microbiology laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 1549–1554. 10.1128/JCM.01794-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzini A., Jaton K., Romo D., Bille J., Prod’hom G., Greub G. (2011). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry as an alternative to 16S rRNA gene sequencing for identification of difficult-To-identify bacterial strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 693–696. 10.1128/JCM.01463-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme K., Fernández-No I. C., Barros-Velázquez J., Gallardo J. M., Calo-Mata P., Cañas B. (2010). Species differentiation of seafood spoilage and pathogenic gram-negative bacteria by MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. J. Proteome Res. 9 3169–3183. 10.1021/pr100047q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme K., Fernández-No I. C., Barros-Velázquez J., Gallardo J. M., Cañas B., Calo-Mata P. (2011). Rapid species identification of seafood spoilage and pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria by MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. Electrophoresis 32 2951–2965. 10.1002/elps.201100217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme K., Fernández-No I. C., Barros-Velázquez J., Gallardo J. M., Cañas B., Calo-Mata P. (2012). SpectraBank: an open access tool for rapid microbial identification by MALDI-TOF MS fingerprinting. Electrophoresis 33 2138–2142. 10.1002/elps.201200074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burillo A., Rodríguez-Sánchez B., Ramiro A., Cercenado E., Rodríguez-Créixems M., Bouza E. (2014). Gram-stain plus MALDI-TOF MS (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry) for a rapid diagnosis of urinary tract infection. PLoS ONE 9:e86915 10.1371/journal.pone.0086915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderaro A., Arcangeletti M. C., Rodighiero I., Buttrini M., Gorrini C., Motta F., et al. (2014). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry applied to virus identification. Sci. Rep. 4 6803 10.1038/srep06803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonnelle E., Beretti J. L., Cottyn S., Quesne G., Berche P., Nassif X., et al. (2007). Rapid identification of Staphylococci isolated in clinical microbiology laboratories by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 2156–2161. 10.1128/JCM.02405-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonnelle E., Grohs P., Jacquier H., Day N., Tenza S., Dewailly A., et al. (2012). Robustness of two MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry systems for bacterial identification. J. Microbiol. Methods 89 133–136. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash P. (2009). Proteomics in the study of the molecular taxonomy and epidemiology of bacterial pathogens. Electrophoresis 1 S133–S141. 10.1002/elps.200900059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassagne C., Pratlong F., Jeddi F., Benikhlef R., Aoun K., Normand A. C., et al. (2014). Identification of Leishmania at the species level with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20 551–557. 10.1111/1469-0691.12387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Y., Chen Y. C. (2005). Characterization of intact Penicillium spores by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19 3564–3568. 10.1002/rcm.2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkaoui A., Emonet S., Fernandez J., Schorderet D., Schrenzel J. (2011). Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for rapid identification of Beta-hemolytic streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 3004–3005. 10.1128/JCM.00240-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkaoui A., Hibbs J., Emonet S., Tangomo M., Girard M., Francois P., et al. (2010). Comparison of two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry methods with conventional phenotypic identification for routine identification of bacteria to the species level. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 1169–1175. 10.1128/JCM.01881-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T. C., Hsu W., Wang C. H., Chen Y. J., Fang J. M. (2011). Rapid and specific influenza virus detection by functionalized magnetic nanoparticles and mass spectrometry. J. Nanobiotechnol. 9 52 10.1186/1477-3155-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christner M., Rohde H., Wolters M., Sobottka I., Wegscheider K., Aepfelbacher M. (2010). Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood culture bottles by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time of flight mass spectrometry fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 1584–1591. 10.1128/JCM.01831-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc C., Nappez C., Drancourt M. (2012). Comparing inactivation protocols of Yersinia organisms for identification with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 26 710–714. 10.1002/rcm.6152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxatto A., Prod’hom G., Greub G. (2012). Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36 380–407. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco M. L., Burnham C. A. (2014). Diafiltration MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry method for culture-independent detection and identification of pathogens directly from urine specimens. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 141 204–212. 10.1309/AJCPQYW3B6JLKILC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann R., Graeber I., Kaesler I., Szewzyk U., von Döhren H. (2005). Rapid screening and dereplication of bacterial isolates from marine sponges of the sula ridge by intact-cell-MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (ICM-MS). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67 539–548. 10.1007/s00253-004-1812-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann R., Malorny B. (2011). Rapid screening of epidemiologically important Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars by whole-cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 4136–4146. 10.1128/AEM.02418-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Kemptner J., Marchetti-Deschmann M., Kubicek C. P., Allmaier G. (2009). Development of a MALDI two-layer volume sample preparation technique for analysis of colored conidia spores of Fusarium by MALDI linear TOF mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 395 1373–1383. 10.1007/s00216-009-3067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue M. J., Best J. M., Smallwood A. W., Kostich M., Rodgers M., Shoemaker J. A. (2007). Differentiation of Aeromonas isolated from drinking water distribution systems using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 79 1939–1946. 10.1021/ac0611420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue M. J., Smallwood A. W., Pfaller S., Rodgers M., Shoemaker J. A. (2006). The development of a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry-based method for the protein fingerprinting and identification of Aeromonas species using whole cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 65 380–389. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downard K. M. (2013). Proteotyping for the rapid identification of influenza virus and other biopathogens. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 8584–8595. 10.1039/c3cs60081e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D., Leyssene D., Chacornac J. P., Kostrzewa M., Schmit P. O., Talon R., et al. (2010). Identification of a variety of Staphylococcus species by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 941–945. 10.1128/JCM.00413-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EI Khéchine A., Couderc C., Flaudrops C., Raoult D., Drancourt M. (2011). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry identification of mycobacteria in routine clinical practice. PLoS ONE 6:e24720 10.1371/journal.pone.0024720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddabra R., Prévost G., Scheftel J. M. (2012). Rapid discrimination of environmental Vibrio by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Microbiol. Res. 167 226–230. 10.1016/j.micres.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström S., Onnerfjord P., Nilsson J., Bengtsson M., Laurell T., Marko-Varga G. (2000). Integrated microanalytical technology enabling rapid and automated protein identification. Anal. Chem. 72 286–293. 10.1021/ac990731l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emonet S., Shah H. N., Cherkaoui A., Schrenzel J. (2010). Application and use of various mass spectrometry methods in clinical microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16 1604–1613. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhard M., Hipler U. C., Burmester A., Brakhage A. A., Wöstemeyer J. (2008). Identification of dermatophyte species causing onychomycosis and tinea pedis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Exp. Dermatol. 17 356–361. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinal P., Seifert H., Dijkshoorn L., Vila J., Roca I. (2011). Rapid and accurate identification of genomic species from the Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab) group by MALDI-TOF MS. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 1097–1103. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everley R. A., Mott T. M., Wyatt S. A., Toney D. M., Croley T. R. (2008). Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry characterization of Escherichia coli and Shigella species. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 19 1621–1628. 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerquist C. K., Garbus B. R., Miller W. G., Williams K. E., Yee E., Bates A. H., et al. (2010). Rapid identification of protein biomarkers of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight-time-of-flight mass spectrometry and top-down proteomics. Anal. Chem. 82 2717–2725. 10.1021/ac902455d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feli G., Dellaglio F. (2007). On the species descriptions based on a single strain: proposal to introduce the status species proponenda (sp. pr.). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 2185–2187. 10.1099/ijs.0.64931-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltens R., Görner R., Kalkhof S., Gröger-Arndt H., von Bergen M. (2010). Discrimination of different species from the genus Drosophila by intact protein profiling using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:95 10.1186/1471-2148-10-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenselau C., Demirev P. A. (2001). Characterization of intact microorganisms by MALDI mass spectrometry. Mass. Spectrom. Rev. 20 157–171. 10.1002/mas.10004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. D., Downard K. M. (2014). Origins of the reassortant 2009 pandemic influenza virus through proteotyping with mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 49 93–102. 10.1002/jms.3310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-No I. C., Böhme K., Gallardo J. M., Barros-Velázquez J., Cañas B., Calo-Mata P. (2010). Differential characterization of biogenic amine-producing bacteria involved in food poisoning using MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. Electrophoresis 31 1116–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L., Sánchez-Juanes F., García-Fraile P., Rivas R., Mateos P. F., Martínez-Molina E., et al. (2011). MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry is a fast and reliable platform for identification and ecological studies of species from family Rhizobiaceae. PLoS ONE 6:e20223 10.1371/journal.pone.0020223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L., Sánchez-Juanes F., González-Avila M., Cembrero-Fuciños D., Herrero-Hernández A., González-Buitrago J. M. (2010). Direct identification of urinary tract pathogens from urine samples by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 2110–2115. 10.1128/JCM.02215-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster A. G. (2013). Rapid Identification of microbes in positive blood cultures by use of the vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 3717–3719. 10.1128/JCM.01679-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs C., Rodloff A. C., Chhatwal G. S., Schellenberger W., Eschrich K. (2007). Rapid identification of Viridans Streptococci by mass spectrometric discrimination. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 2392–2397. 10.1128/JCM.00556-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganova-Raeva L., Ramachandran S., Honisch C., Forbi J. C., Zhai X., Khudyakov Y. (2010). Robust hepatitis B virus genotyping by mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 4161–4168. 10.1128/JCM.00813-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb S., Strimmer K. (2012). MALDIquant: a versatile R package for the analysis of mass spectrometry data. Bioinformatics 28 2270–2271. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P. M., Price G. R., Schooneveldt J. M., Schlebusch S., Tilse M. H., Urbanski T., et al. (2012). Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry to identify vancomycin-resistant enterococci and investigate the epidemiology of an outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50 2918–2931. 10.1128/JCM.01000-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guembe M., Rodríguez-Sánchez B., Ruiz A., Martín-Rabadán P., Rodríguez-Créixems M., Bouza E. (2014). Can MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry be used with intravascular catheters? Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 32 372–374. 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag A., Taylor M. S. N., Johnston K. H., Cole R. B. (1998). Rapid identification and speciation of aemophilus bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 33 750–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh J. D., Green I. M., Ball D., Eydmann M., Millar M., Wilks M. (2013). Rapid identification of bacteria from bioMérieux BacT/ALERT blood culture bottles by MALDI-TOF MS. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 70 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart P. J., Wey E., McHugh T. D., Balakrishnan I., Belgacem O. (2015). A method for the detection of antibiotic resistance markers in clinical strains of Escherichia coli using MALDI mass spectrometry. J. Microbiol. Methods 111 1–8. 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen T. H., Martinez R. J., Chen Y., Lafon P. C., Garrett N. M., Parsons M. B., et al. (2009). Rapid identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by whole-cell matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 6745–6756. 10.1128/AEM.01171-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Chang T. C., Li H., Shi G., Tang Y. W. (2011). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and database for identification of Legionella species. Can. J. Microbiol. 57 533–538. 10.1139/w11-039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Li H., Lu X., Stratton C. W., Tang Y. W. (2010). Mass spectrometry biotyper system identifies enteric bacterial pathogens directly from colonies grown on selective stool culture media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 3888–3892. 10.1128/JCM.01290-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettick J. M., Green B. J., Buskirk A. D., Kashon M. L., Slaven J. E., Janotka E., et al. (2008a). Discrimination of Penicillium isolates by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of- flight mass spectrometry fingerprinting. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22 2555–2560. 10.1002/rcm.3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettick J. M., Green B. J., Buskirk A. D., Kashon M. L., Slaven J. E., Janotka E., et al. (2008b). Discrimination of Aspergillus isolates at the species and strain level by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry fingerprinting. Anal. Biochem. 380 276–281. 10.1016/j.ab.2008.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettick J. M., Kashon M. L., Simpson J. P., Siegel P. D., Mazurek G. H., Weissman D. N. (2004). Proteomic profiling of intact mycobacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 76 5769–5776. 10.1021/ac049410m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazin M., Alber J., Lämmler C., Weitzel T., Hassan A. A., Timke M., et al. (2011). Identification of Trueperella (Arcanobacterium) bernardiae by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis and by species-specific PCR. J. Med. Microbiol. 61 457–459. 10.1099/jmm.0.035774-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooff G. P., van Kampen J. J., Meesters R. J., van Belkum A., Goessens W. H., Luider T. M. (2012). Characterization of β-lactamase enzyme activity in bacterial lysates using MALDI-mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 11 79–84. 10.1021/pr200858r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenheit A., Murugaiyan J., Bauer B., Steuber S., Clausen P.-H., Roesler U. (2013). Identification of Tsetse (Glossina spp.) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time of flight mass spectrometry. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2305 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horneffer V., Forsmann A., Strupat K., Hillenkamp F., Kubitscheck U. (2001). Localization of analyte molecules in MALDI preparations by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Anal. Chem. 73 1016–1022. 10.1021/ac000499f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos-Mallecot Y., Cabrera-Alvargonzalez J. J., Miranda-Casas C., Rojo-Martín M. D., Liebana-Martos C., Navarro-Marí J. M. (2014). MALDI-TOF MS, a useful instrument for differentiating metallo-β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 58 325–329. 10.1111/lam.12203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabák J., Walková R., Studentová V., Chudácková E., Bergerová T. (2011). Carbapenemase activity detection by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 3222–3227. 10.1128/JCM.00984-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idelevich E. A., Schüle I., Grünastel B., Wüllenweber J., Peters G., Becker K. (2014). Rapid identification of microorganisms from positive blood cultures by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry subsequent to very short-term incubation on solid medium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20 1001–1006. 10.1111/1469-0691.12640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina E. N., Borovskaya A. D., Malakhova M. M., Vereshchagin V. A., Kubanova A. A., Kruglov A. N., et al. (2009). Direct bacterial profiling by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for identification of pathogenic Neisseria. J. Mol. Diagn. 11 75–86. 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina E. N., Borovskaya A. D., Serebryakova M. V., Chelysheva V. V., Momynaliev K. T., Maier T., et al. (2010). Application of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the study of Helicobacter pylori. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24 328–334. 10.1002/rcm.4394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina E. N., Malakhova M. V., Generozov E. V., Nikolaev E. N., Govorun V. M. (2005). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (mass spectrometry) for hepatitis C virus genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 2810–2815. 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2810-2815.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y. S., Choi S., Chong E., Kim J. H., Kim S. J. (2014). Rapid detection of Bacillus spore aerosol particles by direct in situ analysis using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 59 177–178. 10.1111/lam.12261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y. S., Lee J., Kim S. J. (2013). Discrimination of Bacillus anthracis spores by direct in-situ analysis of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Bull Korean Chem. Soc. 34 2635–2639. 10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.9.2635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A., Nagy E., Sóki J. ESGAI (ESCMID Study Group on Anaerobic Infections). (2014). Detection of carbapenemase activities of Bacteroides fragilis strains with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Anaerobe 26 49–52. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]