Abstract

Background:

The current West Africa epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD), which began from Guinea in December 2013, has been the longest and deadliest Ebola outbreak to date. With the propagation of the internet, public health officials must now compete with other official and unofficial sources of information to get their message out.

Aims:

This study aimed at critically appraising videos available on one popular internet video site (YouTube) as a source of information for Ebola virus disease (EVD).

Materials and Methods:

Videos were searched in YouTube (http://www.youtube.com) using the keyword “Ebola outbreak” from inception to November 1, 2014 with the default “relevance” filter. Only videos in English language under 10 min duration within first 10 pages of search were included. Duplicates were removed and the rest were classified as useful or misleading by two independent reviewers. Video sources were categorized by source. Inter-observer agreement was evaluated with kappa coefficient. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the Student t-test and Chi-squared test, respectively.

Results:

One hundred and eighteen out of 198 videos were evaluated. Thirty-one (26.27%) videos were classified as misleading and 87 (73.73%) videos were classified as useful. The kappa coefficient of agreement regarding the usefulness of the videos was 0.68 (P < 0.001). Independent users were more likely to post misleading videos (93.55% vs 29.89%, OR = 34.02, 95% CI = 7.55-153.12, P < 0.001) whereas news agencies were most likely to post useful videos (65.52% vs 3.23%, OR = 57.00, 95% CI = 7.40-438.74, P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates that majority of the internet videos about Ebola on YouTube were characterized as useful. Although YouTube seems to generally be a useful source of information on the current outbreak, increased efforts to disseminate scientifically correct information is desired to prevent unnecessary panic among the among the general population.

Keywords: Ebola, information, YouTube, videos

Introduction

The current West Africa epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD), which began from Guinea in December 2013, has been the longest and deadliest Ebola outbreak to date.[1] Ebola's method of transmission makes it amenable to containment by coordinated efforts from the public health community worldwide.[2] Those efforts include measures to keep citizens informed to prevent further spread and undue panic.[3] However, with the propagation of the internet, public health officials must now compete with other official and unofficial sources of information to get their message out. In view of these concerns, we attempted to critically appraise videos available on one popular internet video site (YouTube) as a source of information for EVD.

Materials and Methods

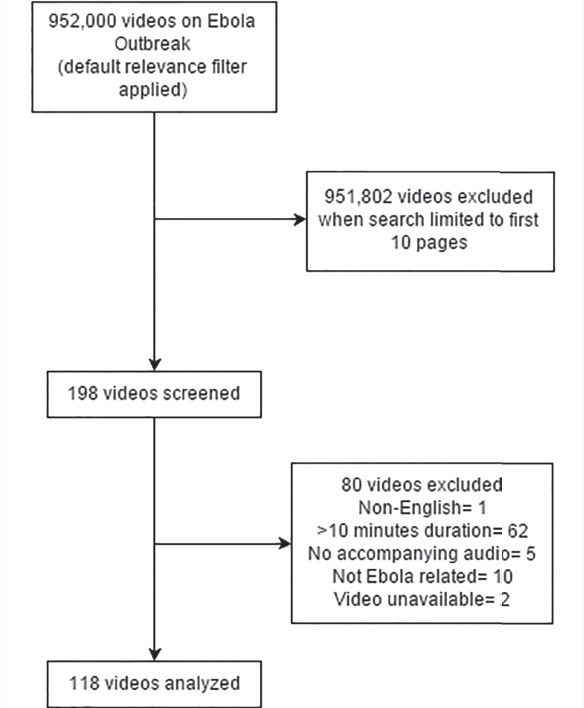

We searched YouTube (http://www.youtube.com) for videos using the keyword “Ebola outbreak” from inception to November 1, 2014 using the default “relevance” filter. The term “Ebola outbreak” was selected as the search term after sampling around 50 YouTube videos related to the Ebola outbreak. We included English language videos with primary content related to EVD with ≤10 min duration and restricted the search results to the first 10 pages [Figure 1]. Duplicate videos, videos without accompanying audio or >10 min duration were excluded. Two independent reviewers classified videos as useful (containing scientifically correct information about any aspect of the disease: epidemiology, symptoms, treatment, prevention) or misleading (containing at least one scientifically unproven information, e. g., EVD as man-made conspiracy or depopulation strategy) using a previously validated method.[4] We extracted the title, length, number of views, number of likes/dislikes, author and date uploaded for the videos. Video sources were also categorized into seven groups (viz. CDC, WHO, Red Cross, NGO/INGOs, academic health institutions/hospitals, news agencies and independent users). Inter-observer agreement was evaluated with kappa coefficient. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed using the Student t-test and Chi-squared test, respectively. A two tailed P - value of <0.05 was considered signifýcant. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for the data analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing systematic video search and selection process

Results

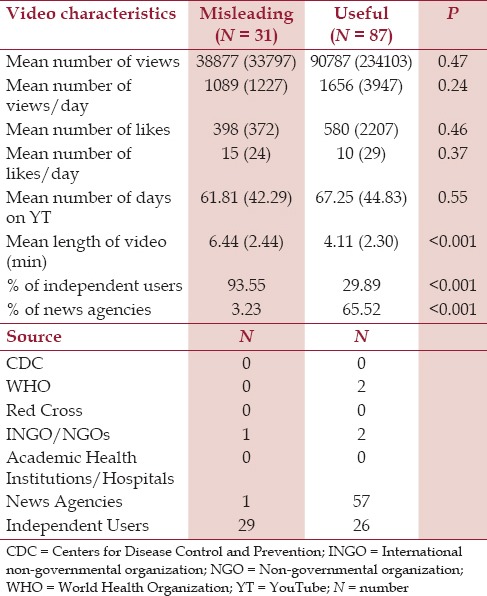

Of the 198 videos screened, 118 videos met the inclusion criteria. 31 (26.27%) videos were classified as misleading and 87 (73.73%) videos were classified as useful. The kappa coefficient of agreement regarding the usefulness of the videos was 0.68 (P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in the mean number of views, mean number of likes, mean number of days on YouTube between the two groups [Table 1]. The mean length of videos classified as misleading was longer than those classified as useful (6.44 vs 4.11 minutes, P < 0.001). Independent users were more likely to post misleading videos (93.55% vs 29.89%, OR = 34.02, 95% CI = 7.55-153.12, P < 0.001) whereas news agencies were most likely to post useful videos (65.52% vs 3.23%, OR = 57.00, 95% CI = 7.40-438.74, P < 0.001) [Table 1]. Examples of fallacious statements recorded from the misleading videos are given in Supplementary Table 1 (1.8MB, tif) .

Table 1.

Detailed characteristics of the misleading and useful youtube videos analyzed

Statements recorded from the YouTube videos classified as misleading

Discussion

Our study shows that majority of the internet videos about Ebola on YouTube were characterized as useful. The popularity of the videos (as measured by number of views and likes/day) between misleading and useful videos was similar. Studies in the past on the role of YouTube as a source of information for H1N1 influenza[4] and immunization[5] have found similar results. Most videos uploaded from news agencies contained correct scientific information. The WHO and CDC were under-represented in the identified video collection (although often quoted in news agency videos) suggesting that those groups do not have immediate primary access to a majority of internet users who use YouTube as a source of information.

Conclusion

Although YouTube seems to generally be a useful source of information on the current outbreak, official health agencies should redouble their efforts to disseminate scientifically correct information on Ebola on sites such as YouTube and prevent unnecessary panic among the general population.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Briand S, Bertherat E, Cox P, Formenty P, Kieny MP, Myhre JK, et al. The international Ebola emergency. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1180–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1409858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gostin LO, Lucey D, Phelan A. The ebola epidemic: A global health emergency. JAMA. 2014;312:1095–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonsalves G, Staley P. Panic, paranoia, and public health - the aids epidemic's lessons for Ebola. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2348–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1413425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandey A, Patni N, Singh M, Sood A, Singh G. YouTube as a source of information on the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keelan J, Pavri-Garcia V, Tomlinson G, Wilson K. YouTube as a source of information on immunization: A content analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2482–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Statements recorded from the YouTube videos classified as misleading