Abstract

Background & objectives:

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most prevalent vaginal infection in women of reproductive age group which has been found to be associated with vitamin D deficiency. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of the administration of 2000 IU/day edible vitamin D for 15 wk to eliminate asymptomatic BV among reproductive age women with vitamin D deficiency.

Methods:

A total of 208 women with asymptomatic BV, who were found to be eligible after interviews and laboratory tests, were randomly assigned to a control group (n=106) or an intervention group (n=105). They used vitamin D drops daily for 105 days. Vaginal and blood samples were taken before and after the second intervention using identical methods (Nugent score for BV diagnosis, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D for vitamin D determination).

Results:

The cure rate of asymptomatic BV was 63.5 per cent in the intervention and 19.2 per cent in the control group (P <0.001). The results showed that being unmarried (P=0.02), being passive smoker (P<0.001), and being in the luteal phase of a menstrual cycle during sampling (P=0.01) were significantly associated with post-intervention BV positive results. After these elements were controlled, the odds of BV positive results in the control group was 10.8 times more than in the intervention group (P<0.001).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Among women in reproductive age group with vitamin D deficiency, the administration of 2000 IU/day edible vitamin D was effective in eliminating asymptomatic BV. This treatment could be useful in preventing the symptoms and side effects of BV.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, reproductive age women, vaginal infection, vitamin D

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) with its high prevalence among vaginal infections is well-known for its adverse effects in pregnancy1 and the reproductive period2. The most important and undesirable consequence of BV is the increased risk of preterm labour in pregnant women3,4, even in asymptomatic infections5. Treatment of symptomatic BV is necessary, but antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic BV is not currently recommended, except among the high risk population6. Asymptomatic women do not have clinical complaints, but the Nugent scores of their vaginal discharge confirm BV. Although the aetiology of BV is not well-known, yet risk factors such as vaginal douching, race, smoking, chronic stress, and local immune deficiency have been considered7.

An important factor is the higher incidence of BV among Blacks8, who have a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency compared to their white counterparts9. Due to the role of vitamin D in the regulation of the immune system10, this finding led to the hypothesis that vitamin D could be a modulator of genital immunity and its deficiency might lead to BV. Bodnar et al11 confirmed the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and BV in pregnant women. Though cross-sectional studies have failed to confirm this relationship in non-pregnant women11,12, more research has been done in this area12. The impact of vitamin D consumption and compensating for its deficiency on eliminating BV has not been studied. The objective of this study was to examine the effect of 2000 IU/day edible vitamin D in eliminating asymptomatic BV among reproductive age women with vitamin D deficiency.

Material & Methods

This placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted between June 2011 and March 2012. The study was performed at the gynaecology clinic of Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran, among reproductive age women. Using 95 per cent power and 95 per cent significance level (two-sided) to detect a 20 per cent success in the experimental group, a sample size of 101 per group (total of 202) was estimated. Due to the risk of loss during the screening process, however, more women were enrolled at the beginning (211).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and was registered at the Registry of Clinical Trials website with No: IRCT201105096284N2. Written consent was obtained from all participants before enrolment.

Women in the age group of 18-35 yr with asymptomatic BV and vitamin D deficiency, who had maintained a stable medical condition during the previous six months, were eligible for the study. Asymptomatic BV was defined by Nugent score and lack of complaint about vaginal odour and/or abnormal discharge on direct questioning. Screening for vitamin D deficiency [serum 25(OH)D < 75 nmol/l] was done for those with confirmed asymptomatic BV. Exclusion criteria were symptomatic BV (because they required antibiotic therapy), any complaint of vaginal itching, burning, and/or irritation on direct questioning, the detection of a vaginal or cervical infection upon gynaecologic examination, pathological obesity, tobacco use, history of hypercalcaemia or nephro-lithiasis, current pregnancy, hepatic or renal dysfunction (based on history), malignancy or malabsorption, the current use of medications that suppress immunity or interfere with vitamin D metabolism, and consumption of vitamin D supplements or antibiotics.

A questionnaire was used to collect data on demographic characteristics, reproductive history, and lifestyle of women. During the first visit, women were screened for BV and vitamin D levels. Screening of BV included two phases: vaginal pH determination and Nugent scoring. Amsel's criteria is not applicable in the diagnosis of asymptomatic BV13; therefore, the pH of vaginal discharge was tested using a colour strip (Universalindikator Merck, Germany). Simultaneously, gynaecological examination was performed using a non-lubricated speculum. Women who had a vaginal pH > 4.5 entered the second phase of BV screening, and samples of their vaginal discharge were collected by Dacron swab. These samples taken from the vaginal wall by swabs were spread on a glass slide and were dried at room temperature. These were passed through the flame of a Bunsen burner several times to induce heat fixation. The vaginal slides were evaluated by Nugent scoring. This scoring system has been considered to be a reliable and cost-effective method for the laboratory evaluation of BV14. In this study, a Nugent score of 7-10 was considered as evidence of BV.

During this screening visit, blood samples were also collected. Serum samples were stored in aliquots at -20°C until the analysis time. EIA (enzymatic immuno assay) kits (Immuno Diagnostic Systems, UK) were used to measure the serum 25(OH)D at the beginning of the study and after the intervention. The serum samples of women confirmed as BV positive were screened for hypovitaminosis. Given the recommended concentration of vitamin D15,16, women with levels below 75 nmol/l were considered vitamin D deficient.

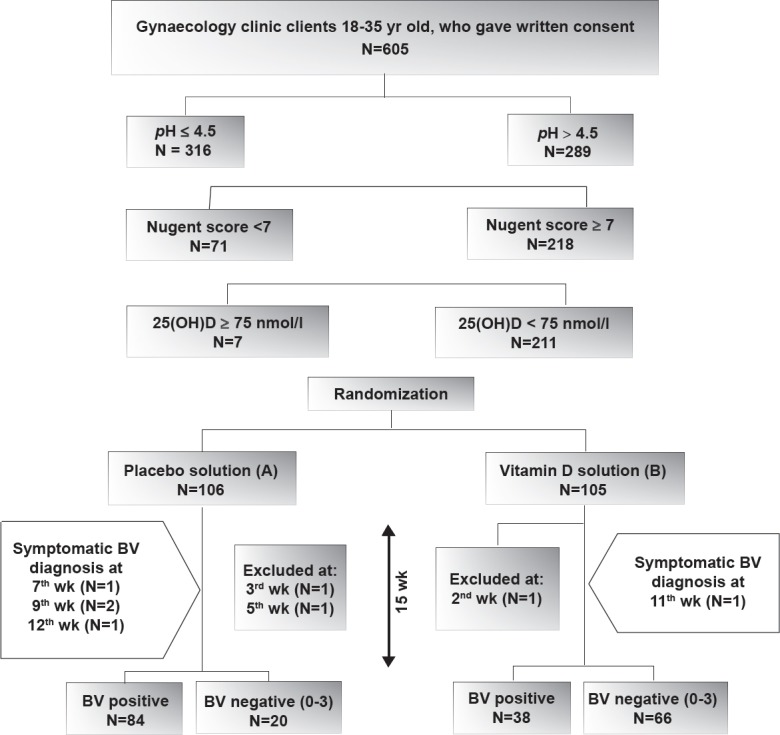

The eligible participants were randomized at the second visit by the block randomization method. A computer-generated randomization was used to create the sequence of allocation; 53 blocks with size of four were used to achieve equal sample sizes across both groups. Each participant had an identification number and was assigned to a study group based on randomization list; 105 participants were randomly entered into the intervention group and consumed two drops/day of vitamin D3 edible oily solution (Equivalent to 2000 IU/day of vitamin D3) with the largest meal of the day17 for 105 days (Figure). This dosage of vitamin D was recommended by the Food and Nutrition Board18. Studies which used this dosage of vitamin D for enhancing immune activity considered a 12-wk intervention19,20. As the participants in this study were vitamin D deficient, so the intervention period was increased to 15 wk.

Figure.

Flowchart showing the trial profile. After screening process, 211 eligible women used 2 drops/day of randomly chosen solutions for 15 wk. Asymptomatic BV was evaluated by Nugent score; score of 0-3 was defined as BV negative (score of 4-6 was not seen at all). Three women did not continue the study.

The control group used placebo drops (sesame oil), which had the same appearance, colour, taste and smell as the vitamin D3 drops, for the same duration. The solutions of vitamin D and placebo were labelled as B and A, respectively; blinding was maintained by concealing information about real constituents of these solutions. Phone calls were made to the participants every two weeks to ensure the proper use of the drops. Participants were instructed to return to the clinic in case of abnormal vaginal discharge. Five women complained of vaginal discharge; they were confirmed to have symptomatic BV during the study using Nugent score (Figure). At this point they stopped the solution intake and were referred to a gynaecologist. Due to the importance of this outcome, however, we computed them as a persistent BV positive in data analysis.

After 15 wk, participants were told to stop the intake of solutions and were referred to the clinic. At this follow up visit, vaginal and blood samples were collected again and analyzed. A clinical cure of asymptomatic BV was defined as having a Nugent score of 0-3.

At the end of the study, women were informed of their group, BV status, and level of vitamin D.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using the SPSS 16.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The chi-squared test was used to compare distributions of independent variables between the two groups and by asymptomatic BV status (after intervention). Regression logistic was used to control confounding variables.

Results

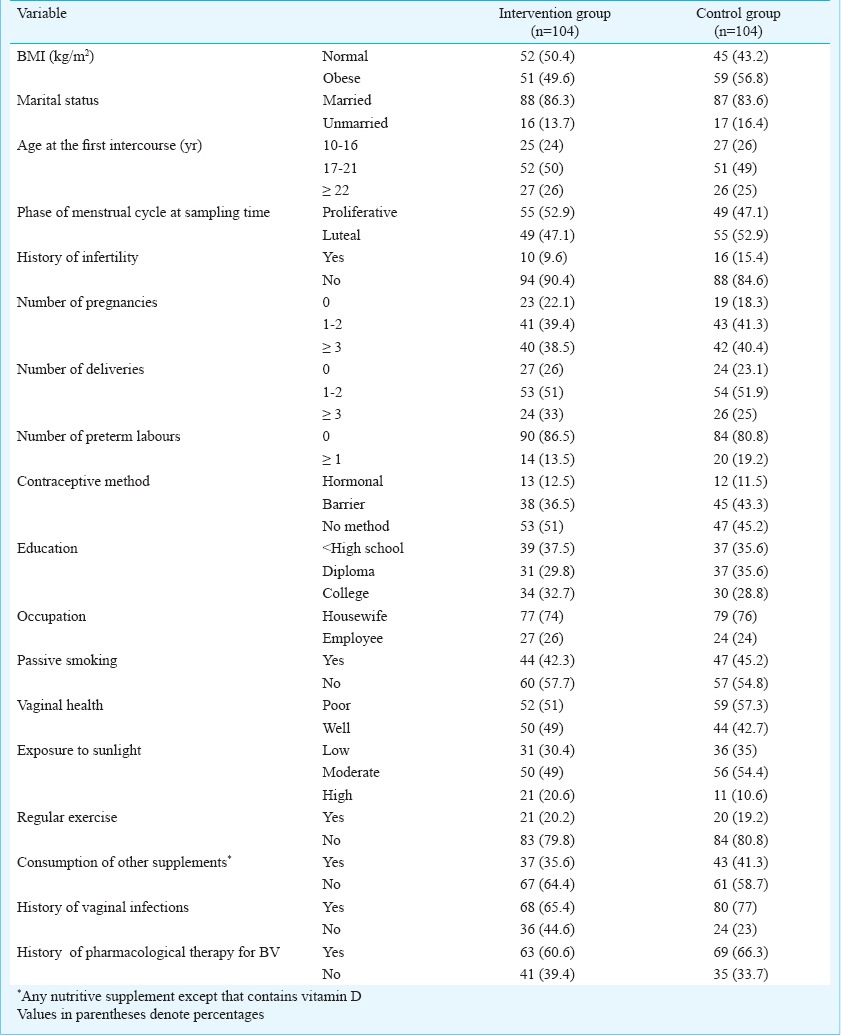

Of the 211 women, three (1 from the control group and 2 from the intervention group) were excluded in the first weeks of the study (2 women did not continue use of the drug; 1 woman used antibiotics). The average age of the 208 study participants was 29.4 ± 4.8 yr (range 18-35 yr); the average age of women was 29.6 ± 4.5 yr in the control group and 29.2±5.0 yr in the intervention group. Table I presents characteristics of the study participants in the two groups. No significant difference was found in any of the parameters between the two groups.

Table I.

Characteristics of the participants included in the study

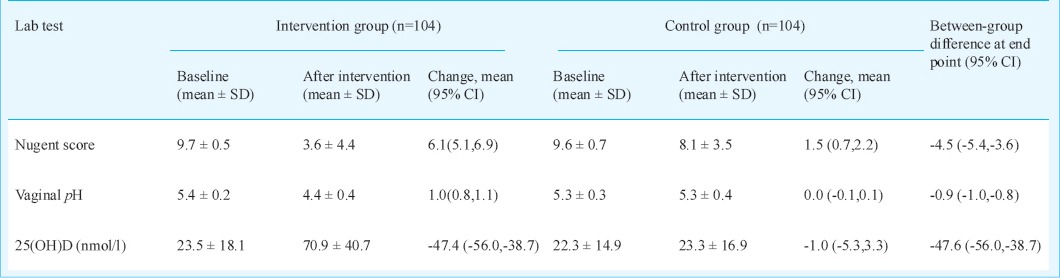

Table II demonstrates the mean values of Nugent score, vaginal pH and serum 25(OH)D; the changes of these values in the two groups are shown with 95% CI (confidence interval).

Table II.

mean values of laboratory test results

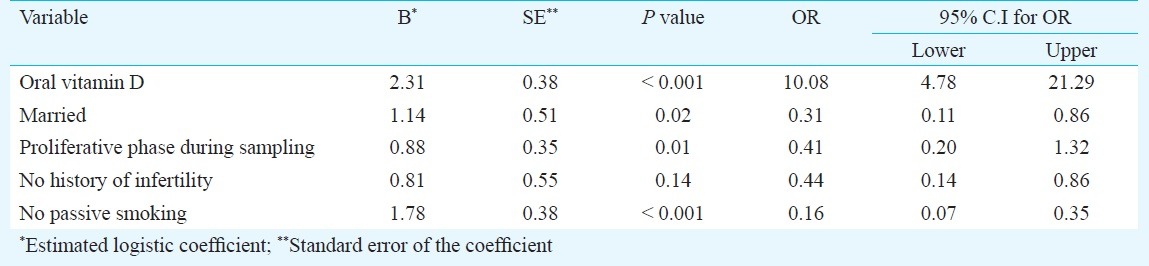

The cure rate was 63.5 per cent in the intervention and 19.2 per cent in the control group (P <0.001). Intervention, marital status, menstrual phase at the time of sampling and passive smoking had significant relationships with the dependent variable (bacterial vaginosis) (Table III).

Table III.

Outcomes of logistic regression analysis for controlling confounding factors on elimination of bacterial vaginosis

Being married, sampling in the proliferative phase, and not being a passive smoker increased the chance of BV clearance after the intervention.

Discussion

Our results showed that the use of 2000 IU/day vitamin D for 15 wk was an effective treatment method for asymptomatic BV among vitamin D-deficient, reproductive age women. The findings also indicated that married status, not being a passive smoker, and being in the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle during sampling, were related to the cure of BV. A high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among reproductive age group women was seen in (97%, 211/218) the study participants; 36 per cent of our participants (218/605) were confirmed as having asymptomatic BV. Bodnar et al12 found that the prevalence of BV decreased when vitamin D levels were elevated. Hensel et al12 used data from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) and reported that the association between BV and vitamin D deficiency was meaningful only among pregnant women; in non-pregnant women, this relationship was not confirmed. This finding could be due to higher amounts of circulating 25(OH)D in pregnant women21. The production of cathelicidins is higher among pregnant women, and it can lead to more immunity against BV. Intervention using a daily and constant dosage of vitamin D might be appropriate for increasing the circulating 25(OH)D in the non-pregnant women as done in the current study.

The effect of vitamin D on BV elimination can be explained by the impact of vitamin D on the immune system, especially in the local immunity of the vagina. Cytokines were considered the main factor linking BV and vitamin D11,22. Yusupov et al20 evaluated the effectiveness of 2000 IU/day of vitamin D on serum cytokines levels and found it to be ineffective. They proposed that cytokines could not be the mediating factor between vitamin D and asymptomatic BV, although Ryckman et al23 reported a significant difference between the cytokines and chemokines of BV positive and negative women. It has been suggested that adequate levels of 25(OH)D can protect women from BV by aiding in the production of cathelicidins24. Based on these findings, our assumption is that higher serum 25(OH)D levels increase the production of cathelicidins and thereby enhance the immunity of the genital tract. BV clearance in the control group could be due to the improvement in vaginal health. We did not repeat the questionnaire at the end of the intervention, so analysis of these changes was not possible. The failure of some women to respond to treatment could be due to concurrent parameters weakening vaginal immunity.

Almost all of our participants were vitamin D-deficient, while Bodnar et al25 demonstrated that only 46 per cent of Black women (the high risk population) from the USA were vitamin D-deficient. This considerable difference may be partly explained by cultural and social behaviours of women in this study. Because of high percentage of vitamin D deficiency among Iranian mothers (86%)26 and similar findings of the current study, prevention and treatment policies should be applied in the general population.

In a trial, the same dosage of vitamin D was used to increase serum cytokines20, the percentage of people with normal levels of vitamin D (>75 nmol/l) rose from 23 to 73 per cent in the intervention group, whereas in our intervention group levels of vitamin D before and after intervention were 0 and 46.2 per cent, respectively.

It has been demonstrated that everyone does not have the same response of serum 25(OH)D level to the standard treatment; difference in response of vitamin D levels is not related to the age27. But in the current study we found that it could be related with parity and gravidity. Frequent pregnancies could lead to severe reduction of maternal vitamin D reserves for a long time. This deprivation can decrease the response to vitamin D treatment. The dosage of vitamin D used in the current had no adverse effects. The safety of a dose of 4000 IU/day for at least six months for pregnant women was confirmed by Hollis et al28.

Risk factors of asymptomatic BV resistance recognized in our study had been identified as the risk factors of BV in another research29,30. Smoking is known to have an adverse effect on the metabolism of vitamin D31 which can lead to vitamin D deficiency32 and make treatment difficult. Mania-Pramanik et al33 revealed that BV and infertility were significantly associated, regardless of tubal damage. In our study, a positive history of infertility (in the past years and not currently) was related to BV, but the relationship was not meaningful.

The main strength of this study was the measurement of 25(OH)D in two stages (baseline and after intervention). The lack of laboratory analysis of factors such as parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcium and phosphorous, the inability of the dosage or duration of intervention to increase the level of vitamin D in participants to normal ranges for all cases, and the lack of investigation into the immune factors at both stages of the study were weaknesses of this clinical trial; genital co-infections were not evaluated by standard laboratory tests before or after the intervention, so their rates were disregarded. The limitations of this study were performing vitamin D measurements in two different seasons, and not using DNA-based tests to enhance sensitivity and specificity for BV detection. In the current study, vaginal sampling from women was performed without considering their menstrual cycle phase. It would have been better to consider sampling in the proliferative phase as an inclusion criterion. Adding a follow up period for the evaluation of serum 25(OH)D levels and BV status would be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, the treatment of vitamin D deficiency using 2000 IU/day edible vitamin D for 15 wk was an effective way to cure the asymptomatic BV. We recommend vitamin D therapy for the prevention or management of BV among deficient women. By treating vitamin D deficiency, preterm labour and other adverse effects of BV may be prevented.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded and supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS); grant no: 90-01-28-13331.

References

- 1.Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Kalinka J. Correlations of selected vaginal cytokine levels with pregnancy-related traits in women with bacterial vaginosis and mycoplasmas. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;78:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Vaneechoutte M, Temmerman M. The epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis in relation to sexual behaviour. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey JC, Klebanoff MA. Is a change in the vaginal flora associated with an increased risk of preterm birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1341. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.069. discussion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donders GG, Van Calsteren K, Bellen G, Reybrouck R, Van den Bosch T, Riphagen I, et al. Predictive value for preterm birth of abnormal vaginal flora, bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis during the first trimester of pregnancy. BJOG. 2009;116:1315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leitich H, Kiss H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:375–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neggers YH, Nansel TR, Andrews WW, Schwebke JR, Yu KF, Goldenberg RL, et al. Dietary intake of selected nutrients affects bacterial vaginosis in women. J Nutr. 2007;137:2128–33. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:114–20. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000247627.84791.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Looker AC, Dawson-Hughes B, Calvo MS, Gunter EW, Sahyoun NR. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of adolescents and adults in two seasonal subpopulations from NHANES III. Bone. 2002;30:771–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin JS, Choi MY, Longtine MS, Nelson DM. Vitamin D effects on pregnancy and the placenta. Placenta. 2010;31:1027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodnar LM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Maternal vitamin D deficiency is associated with bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Nutr. 2009;139:1157–61. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.103168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hensel KJ, Randis TM, Gelber SE, Ratner AJ. Pregnancyspecific association of vitamin D deficiency and bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:41.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGregor JA, French JI. Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55(Suppl 1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200005001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohanty S, Sood S, Kapil A, Mittal S. Interobserver variation in the interpretation of Nugent scoring method for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:18–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Optimal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels for multiple health outcomes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;624:55–71. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulligan GB, Licata A. Taking vitamin D with the largest meal improves absorption and results in higher serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:928–30. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1997. Institute of Medicine (US). Dietary reference intakes: for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li-Ng M, Aloia JF, Pollack S, Cunha BA, Mikhail M, Yeh J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation for the prevention of symptomatic upper respiratory tract infections. Epidemiol infect. 2009;137:1396–404. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusupov E, Li-Ng M, Pollack S, Yeh JK, Mikhail M, Aloia JF. Vitamin D and serum cytokines in a randomized clinical trial. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:pii–305054. doi: 10.1155/2010/305054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D and pregnancy: skeletal effects, nonskeletal effects, and birth outcomes. Calcif tissue int. 2013;92:128–39. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yudin MH, Landers DV, Meyn L, Hillier SL. Clinical and cervical cytokine response to treatment with oral or vaginal metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:527–34. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Racial differences in cervical cytokine concentrations between pregnant women with and without bacterial vaginosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;78:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant WB. Adequate vitamin D during pregnancy reduces the risk of premature birth by reducing placental colonization by bacterial vaginosis species. mBio. 2011;2:e00022–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Powers RW, Frank MP, Cooperstein E, Roberts JM. High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in black and white pregnant women residing in the northern United States and their neonates. J Nutr. 2007;137:447–52. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazemi A, Sharifi F, Jafari N, Mousavinasab N. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and their newborns in an Iranian population. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:835–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan P. Vitamin D therapy in clinical practice. One dose does not fit all. Int J clin pract. 2007;61:1894–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double-blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2341–57. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Thorp JM, Jr, Herring AH. Psychological and biological markers of stress and bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. BJOG. 2007;114:216–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorsen P, Vogel I, Molsted K, Jacobsson B, Arpi M, Moller BR, et al. Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: a population-based study on Danish women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:906–11. doi: 10.1080/00016340500432655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brot C, Jorgensen NR, Sorensen OH. The influence of smoking on vitamin D status and calcium metabolism. Eur j clin nutr. 1999;53:920–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao G, Ford ES, Tsai J, Li C, Croft JB. Factors associated with vitamin D deficiency and inadequacy among women of childbearing age in the United States. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:691486. doi: 10.5402/2012/691486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mania-Pramanik J, Kerker SC, Salvi VS. Bacterial vaginosis: a cause of infertility? Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:778–81. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]