Abstract

Background:

Mental health disorders affect around 500 million people worldwide. In India, around 10–12% of people are affected by a mental disorder either due to stress, depression, anxiety, or any other cause. Mental health of workers affects the productivity of the workplace, with estimates putting these losses to be over 100 million dollars annually.

Aims:

The study aims to measure depression, anxiety, and stress levels of workers in an industry and to investigate if it has any effect on productivity of the firm.

Materials and Methods:

The study utilized a cross-sectional design and was conducted among workmen of the firm. A sociodemographic based questionnaire and a mental health screening tool -Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)-21 were used for the same. A total of 90 completed questionnaires were analyzed for the study. The data was analyzed for central tendencies as well as for any associations and correlations.

Results:

The study showed that none of the workers had a positive score for depression. It also showed that around 36% of the workers had a positive score for anxiety and 18% of the workers had a positive score for stress on DASS-21 scale. The odds ratio between stress and number of leaves taken by a worker in the last 3 months suggested a dose–response relationship, but was statistically insignificant.

Conclusion:

The study found a prevalence rate of around 18–36% for anxiety and stress amongst the workers at the factory. Large-scale studies will help understand the effect mental health status has on the Indian workplace.

Keywords: DASS-21, India, mental health, productivity, workplace

The World Health Organization (WHO) in 2011-“Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” More than 450 million people suffer from a type of mental disorder.[1] Among the mental health disorders; depression, anxiety, and stress form a large proportion.

Mental health disorders account for 13–14% of the world's total burden from ill-health.[2] India is estimated to have 10–20 persons out of 1,000 suffer from severe mental illness and three to five times more have an emotional disorder.[3] India has a 1-year prevalence rate of depression from 5.8 to 9.5.[3] The prevalence rate for anxiety disorders is around 16.5.[4] In India, prevalence of moderate level of stress was reported at 9.5% in a study which also found most stressors were work related.[5]

It has long been known that the workplace and mental health of workers have a complex relationship. Work as itself can often have a positive impact on the mental health of a person—job security, time structure, social contact, and organizational abilities can often elevate a person's state of well-being.[6] However, adverse mental health of workers can also disrupt work. Increased absenteeism, decreased productivity, and profits as well as costs to deal with the problem all eat into an employer's economic viability.[7] Depression and anxiety patients can have occupational role dysfunction and stress at the workplace leads to an unhealthy environment. A mentally healthy workplace has high productivity levels and is efficient, and is open to discussions about mental health issues.[8]

In ‘Mental Health at Work: Developing the Business Case’, the Centre for Mental Health estimated that stress, anxiety, and depression cost employers an (inflation-adjusted) 1,149 pounds per year for every employee in the workforce.[9]

Around 98 million people are working in India, most of them in the unorganized sector.[10] There are no laws or regulation related to mental health of employees in firms—organized or not. While observing this scenario as outlined above, it is imperative that we collect more evidence for the same. This study is a pilot study, to test the viability of such a project in India as well as to see if India leans in with global forecasts and towards finding a result, which will overhaul some policy and regulatory decision about mental health in the workplace. The objectives of the study are as follows:

To determine the depression, anxiety, and stress levels of workers in an industrial firm

To investigate the association between depression, anxiety, or stress and productivity of the firm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical considerations

The study proposal along with its intended aims and objectives was cleared by the Institutional Ethical Review Board at the authors’ college. Permission was taken from the Human Resources (HR) department of the factory after explaining the study, its objectives, and methodology. Informed consent was taken from each of the workers who took part in this study. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary and employees received no benefit for the same. All data was handled confidentially.

For this study we used a cross-sectional study and quantitative research method to collect and analyze the data. The data was collected personally by the authors from the workers at the industrial workplace site.

Study basis and study design

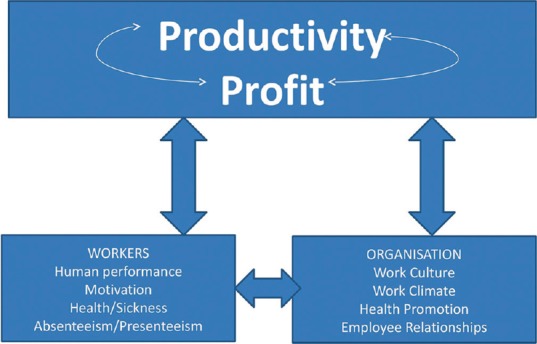

Productivity is defined as output per unit of input per time. Input can be processes, labor, and strategies. In this study we focus on the workers. Leaves taken totally (sick or otherwise) were taken as work impairment days and calculated as a factor. In addition to determine any cost to the company, accidents and the compensation paid out was also asked for. It was based on Figure 1. The study was done at an industrial firm which is a multinational corporation (MNC) in Bangalore, India. The objectives of the study as well as the beneficial aspect of the study to their firm were explained to the factory management.

Figure 1.

Cycle of productivity on which the study was based

The study was conducted over a period of 3 months including the required permissions. The workers had three shifts; one each in the morning, afternoon, and night. The study was conducted on only workmen of the factory. Inclusion criteria included any workman in the factory who had worked for more than a year and gave consent for the study.

The authors personally visited the factory premises to conduct the study. A total of 167 questionnaires were distributed among the workers, who numbered over 300. A total of 97 were collected back. Seven questionnaires were filled incorrectly, incompletely, or ambiguously and were arbitrarily dropped out of the study. Ninety questionnaires (54% response rate) were eventually analyzed.

Study tools

The study used self-administered questionnaires as its tool. Two questionnaires were distributed. The questionnaires used were in Kannada, the official language of the state of Karnataka. The forward-backward translation method was used using two different translators for the same:

A sociodemographic based questionnaire which also asked abouta) comorbidities and treatment for the same, (b) accidents at the workplace in the last 6 months and treatment/compensation for the same, and (c) leaves and sick leaves taken in the last 3months

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)-21: The DASS-21 is based on three subscales of depression, stress, and anxiety and each subscale consists of seven questions each.[11] Each subscale comprises of seven statements regarding how the test subject was feeling over the last week and four responses ranging from 0- did not apply to me at all, 1- applied to me some of the time, 2- applied to me for a considerable amount of time to 3- applied to me very much/most of the time. The scoring system is of the Likert type and the total score for each subscale gives the severity of that very symptom which has a range from 0 to 21 for each subscale. Both English and non-English versions have high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha scores >0.7).[12]

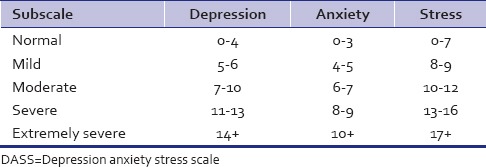

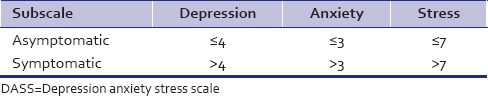

The DASS is not a diagnostic test for mental health disorders and does not aim to be so. The cutoffs used in this study were as suggested by the Black Dog Institute, Australia[13] as shown in Table 1, however, we combined the various severities and classified them as symptomatic and asymptomatic. The technical quality of the DASS in an occupational health setting has been studied and validated.[14]

Table 1.

DASS- 21 scores according to severity[12]

Statistical analysis

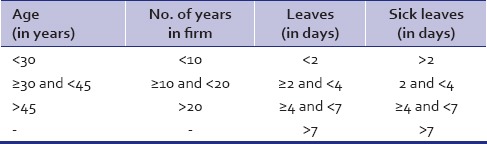

All data collected was logged and keyed in Microsoft Excel (2010) and was analyzed using IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 20.0. Descriptive statistics of mean, median, range, and standard deviation were analyzed for the continuous variables of age and work experience at the firm. Frequencies for the other variables were studied and presented as categories [Table 2]. Associations between variables and the scores on DASS-21 were studied using the Pearson's Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests where appropriate. A P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered significant. The DASS-21 score were dichotomized for the purpose of this study into asymptomatic and symptomatic groups based on their subscale scores [Table 3]. A model to test the relation between DASS-21 scores and the variables was analyzed using logistic regression and with 95% confidence interval (CI) levels not including 1.00 considered significant.

Table 2.

Variables categorised for analysis

Table 3.

DASS-21 score cut offs used for the study

RESULTS

Data of 90 workers was analyzed. The results are as follows:

Number of males: 90/90

Education background: All 90 had a diploma, as it was a prerequisite to work for the firm.

Marital status: Married-86; unmarried-3; and divorced-1

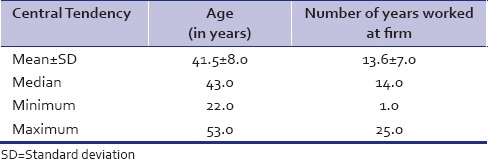

Around 44 workers were within the 30–45 years group and around 35 had worked between 10–20 years at the factory. Twenty-six workers had also worked for more than 20 years at the factory. Table 4 shows the wide range of the workers ages and their experience at the firm.

Table 4.

Central tendencies of age and number of years worked at the firm

Around 36% (n = 33) of the workers had a symptomatic score on the Anxiety subscale and 18% (n = 16) on the Stress subscale. No workers had a symptomatic depression score. Around 14% of workers (n = 13) had a positive score on both the Anxiety and Stress subscales.

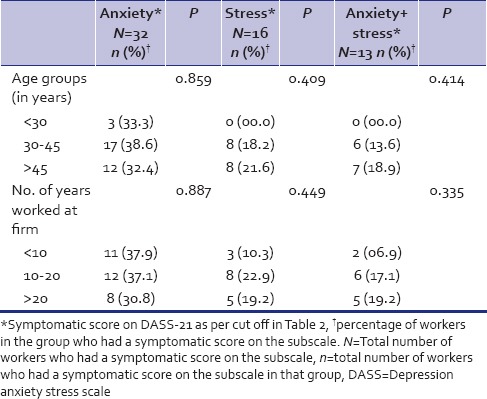

Table 5 shows the number of workers who had a symptomatic score on subscales of DASS-21and the factors that could have a bearing on the score, that is, within the various age groups and work experience, with their associations.

Table 5.

Frequencies and associations of worker's age and firm experience with DASS-21 subscores

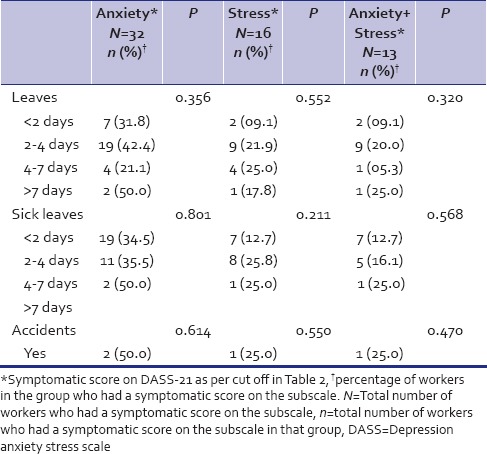

Table 6 shows the associations and frequencies of productivity as determined by number of leaves and sick leaves taken as well as accidents and the DASS-21 subscale symptomatic scores. There were no statistically significant associations between the leaves, sick leaves, accidents, and the Anxiety and Depression subscale symptomatic scores.

Table 6.

Frequencies and associations of ‘productivity’ variables and DASS-21 subscores

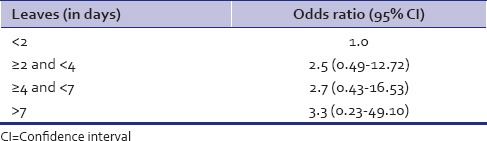

Logistic regression and odds ratio were analyzed for the variables of age, firm experience, leaves, sick leaves, and accidents in the last 6 months with the respective DASS-21 subscores (bivariate analysis). The results were statistically insignificant, hence multivariate analysis was not analyzed. However, we found a pattern suggestive of a dose–response relationship between stress and number of leaves taken during the last 3 months as shown in Table 7. However, similar patterns did not emerge for other variables.

Table 7.

Odds ratio between symptomatic stress scores and number of leaves taken in last 3 months

DISCUSSION

None of the workers scored a ‘symptomatic’ score on the Depression subscale, which is in contrast to a 9.1% prevalence of depression in Bangalore.[15] This asks the question whether optimum work prevents depression. Or are employed people happier than unemployed? This rhetoric has many complexities; however, the risk of depression in unemployed has been shown to be higher than those employed.[16]

The workers had a prevalence of 36% on the Anxiety subscale in contrast to a prevalence of 8.4% in Bangalore.[15] Inspite of such a high prevalence, we were unable to find a comorbid relationship with depression.[17]

Stress subscale positive scores had a prevalence of 18% compared to the global estimates of around 20%.[1] An increased risk of work-related illnesses and accidents has been observed in southeast Asian countries that have experienced rapid industrialization.[5]

While talking about correlations and associations, there was a suggestive dose–response relationship between number of leaves taken and the stress and anxiety scores, however they were statistically insignificant, most probably due to the small sample size. However, no accidents were found to be related either to positive stress or anxiety scores even though around 60% of accidents can be attributed to stress.[18]

In the Indian set up, studies, though rare, have been done to determine the mental health status and the factors that are associated with them. A study done earlier on industrial workers showed similar prevalence of 17–30% of mental health disorders like this study did.[19] However, a similar study in southern India showed a higher prevalence of around 40–50% psychiatric morbidity among industrial workers.[20] Associations with age, gender, and education have been found as well.[21]

In this study there is the issue of potential selection bias, which may not be remedied by a larger sample size. The workers who were on leave for those 3 days were not accounted for in this study. Due to trust issues, there is a possibility that those who did indeed have mental health issues did not take part in the study. This could have led to an underestimation or overestimation of the problem in certain areas. In this study we used variables like leave, sick leave, and accidents to interpret productivity; but productivity has many more dependent variables. In addition, leaves and accidents can depend on a host of factors and mental status is only a fraction of that. The dichotomization of the DASS-21 scores for analysis was necessary in a study with a smaller sample size, but the risk of losing a grading score on severity of a subscale was collateral damage.

CONCLUSIONS

This study was undertaken to study the depression, anxiety, and stress levels in an industrial set up and to investigate whether adverse conditions affected the productivity of the firm. The workers showed a prevalence ranging from 18 to 36% of mental health disorders over the three subscales of Depression, Stress, and Anxiety. Only longitudinal studies can demonstrate if a causal effect does actually exist. Studies on how health of workers is affected by their work is as closely related and needed as studies on how a workers health is affected by their work. Developing countries have no watchdogs that can regulate industries and occupational health, which if left unsolved, can lead to unwarranted situations regarding the health of workers.[1]

Recommendations

The following are some recommendations in an effort to promote mental health in workplaces:

More research and studies in this field to gather more evidence of the ill-effects of adverse mental health on workers as well as on the economy, especially for developing countries

Need to involve more sectors as well as higher grades of workers in the studies

-

To follow WHO guidelines[1] which are:

- Increasing an employer's awareness of mental health issues

- Identifying common goals and positive aspects of the work process

- Creating a balance between job demands and occupational skills

- Training in social skills

- Developing the psychosocial climate of the workplace

- Provision of counseling

- Enhancement of working capacity and

- Early rehabilitation strategies

Legislation and policy regarding mental health; not only in the public domain but also with regards to the workplace should be set up and strictly adhered to

Framework to ensure correct, swift diagnosis for mental disorders as well as rehabilitatory facilities to ensure smooth and quick recovery.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murthy RS, Haden A, Campanini B, editors. Geneva: 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. World Health Report; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health Foundation, UK: Economic burden of Mental Health Illness cannot be tackled without Research Investment. [Last cited on 2010 Nov]. [Internet] Available from: http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/content/assets/PDF/campaigns/MHF-Business-case-for-MHresearch-Nov2010.pdf .

- 3.Geneva: 2010. [Last cited on 2010 Sept]. WHO Statistics, India, World Health Organisation. [Internet] Available from: http://www.who.int/countries/ind/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganguli HC. Epidemiological finding on prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra B, Mehta S, Sinha ND, Shukla SK, Ahmed N, Kawatra A. Evaluation of workplace stress in health university workers: A study from rural India. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:39–44. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.80792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harnois G, Gabriel P. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2000. Mental Health: Issues, Impact and Practices; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajgopal T. Mental well-being at the workplace. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2010;14:63–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.75691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava K. Mental health and industry: Dynamics and perspectives. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mental Health at Work: Developing the business case, Centre for Mental Health. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 15]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/pdfs/mental_health_at_work.pdf .

- 10.Provisional Report of Economic Census 2005. All India Report. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 14]. [Internet]. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/economic_census_prov_results_2005.pdf .

- 11.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackdog Instituite, Australia. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 10]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/docs/3.DASS21withscoringinfo.pdf .

- 14.Nieuwenhuijsen K, de Boer A, Verbeek J, Blonk R, Van F. The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS): Detecting anxiety disorder and depression in employees absent from work because of mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:77–82. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg DP, Lecrubier Y. Form and frequency of mental disorders across centres. In: Ûstün TB, Sartorius N, editors. Mental illness in general health care: An international study. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons on behalf of WHO; 1995. pp. 323–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jefferis BJ, Nazareth I, Marston L, Moreno-Kustner B, Bellón JÁ, Svab I, et al. Associations between unemployment and major depressive disorder: Evidence from an international, prospective study (the predict cohort) Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:1627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschfeld R. The Comorbidity of Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Recognition and Management in Primary Care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:244–54. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Institute of Stress. “Job Stress.”. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 28]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.stress.org/job.htm .

- 19.Kar N. Mental health in an Indian industrial population: Screening for psychiatric symptoms. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2002;6:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar PK, Jayaprakash K, Francis P, Bhagavath P. Psychiatric Morbidity in Industrial Workers of South India. JCDR. 2011;5:921–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh A. Age, education, mental health of industrial workers. Indian J Occupational Health. 1992;35:64–9. [Google Scholar]