Abstract

Background:

Doctors have been identified as one of the key agents in the prevention of alcohol-related harm, however, their level of use and attitudes toward alcohol will affect such role.

Aim:

This study is aimed at describing the pattern of alcohol use and the predictors of hazardous drinking among hospital doctors.

Setting:

Study was conducted at the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

Design:

A cross-sectional survey involving all the doctors in the teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods:

All the consenting clinicians completed a sociodemographic questionnaire and alcohol use was measured using the 10-item alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) and psychological well-being was measured by the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).

Statistical Analysis Used:

Statistical analyses were done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16. Chi-square tests with Yates correction were used to describe the relationship between respondent's characteristics and AUDIT scores as appropriate.

Results:

There were a total of 122 participants. Eighty-five (69.7%) of them were abstainers, 28 (23%) were moderate drinkers, and 9 (7.3%) hazardous drinkers. With the exception of age, there was no significant relationship between sociodemographic status, years of practice, specialty of practice, and hazardous alcohol use. Experiencing stress or GHQ score above average is significantly associated with hazardous drinking.

Conclusion:

Hazardous drinking among hospital doctors appears to be essentially a problem of the male gender, especially among those older than 40 years. Stress and other form of psychological distress seem to play a significant role in predicting hazardous drinking among doctors.

Keywords: Alcohol, alcohol use disorder identification test, doctors, hazardous drinking, predictors

Hazardous drinking is a pattern of alcohol consumption that increases the risk of harmful consequences for the user or others.[1,2] Doctors, on the other hand, have been identified as one of the key factors in the prevention of alcohol-related harm. Nevertheless, their lifestyle and their attitudes toward alcohol will affect such role.[3] The degree of effort a doctor makes on activities to prevent hazardous alcohol use in patients will depend on several factors; an important one of these being his own individual use.[4,5]

Previous studies from Western countries have shown that doctors have high levels of alcohol consumption; even higher than the general population and run an increased risk of alcohol-related diseases.[6,7,8] In addition, alcohol exerts a negative effects on the individual's physical and mental health, their families, and threatens the ability to provide adequate patient care and the individual's role as a teacher and a role model for healthy lifestyles[9,10,11] In Nigeria, there are limited studies looking at alcohol use among doctors. In a study by Issa et al.[12] the level of risky alcohol use among doctors in their study was lower than that of the general population and predominantly men's issue.[13,14]

There has been an increasing emphasis on the role of doctors in the prevention and management of alcohol-related harm;[15,16] however, this will depend on their level of use. This study is aimed at looking at the pattern of alcohol use and predictors of hazardous drinking among doctors in a hospital setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a cross-sectional survey involving all the doctors in the service of State University Teaching Hospital in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

Data were collected using a pretested, semi-structured questionnaire incorporating sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) questionnaire and the 12 items General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) were used to assess level of alcohol use and psychological well-being, respectively. A set of questionnaires containing sociodemographic questionnaire, GHQ-12 and the AUDIT was given to all consenting doctors.

The AUDIT, a self-rated 10-item questionnaire was used to assess harmful and hazardous alcohol use.[17] It was developed by Saunders et al. as part of the WHO collaborative project on the detection and management of alcohol-related problems in Primary Health Care.[18] The AUDIT at a cut-off of 5 and above could clearly identify participants with alcohol-related problems in Nigeria.[19] In this study, a score of 0–4 on AUDIT was rated moderate alcohol use while a score of 5 and above was rated hazardous use. GHQ-12 was used to assess their psychological well-being/distress within the past few weeks. Each item on the scale has four responses from “better than usual” to “much less than usual.” In this study, the GHQ scoring method (0-0-1-1) was chosen against the Likert scale of 0-1-2-3. This particular method is believed to help eliminate any biases which might result from the respondents who tend to choose responses 1 and 4 or 2 and 3, respectively.[20,21] The total score was obtained by adding all scores on each item on the scale. The mean GHQ score for the population of respondents was taken as a rough indicator for the best cut-off point as suggested by Goldberg et al.[22] As such, with a mean GHQ score of 0.89 ± 1.63 for this sample, a cut-off point of 2 was used to determine the respondents’ level of psychological well-being.

Prior to data collection, permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital. The instructions for completion of the questionnaires, a consent form, and a declaration on the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents was attached to the questionnaire.

Statistical analyses were done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc. USA). A descriptive statistics was performed to determine the distribution of characteristics of all the variables studied, including the participants’ alcohol use as assessed by AUDIT and level of psychological well-being as assessed by GHQ-12. The total, means and standard deviation for the GHQ and AUDIT scores were calculated. Chi-square tests with Yates correction were used to describe the relationship between respondent's characteristics and AUDIT scores as appropriate. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 135 respondents who were given questionnaires, 122 returned the completed questionnaires, thus giving a response rate of 90.4%. The mean age of the participants was 35.65 ± 8.35, the mean years of practice was 8.52 ± 7.91, the mean AUDIT and GHQ scores were 1.14 ± 2.87 and 0.89 ± 1.63, respectively. There was a correlation between GHQ score and AUDIT scores (P = 0.000).

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics. The majority of doctors were male (61%), younger than 40 years (79%), married (68.9%), had only practiced for <10 years (68%) and in nonsurgical specialty (68%).

Table 1.

Subjects characteristics

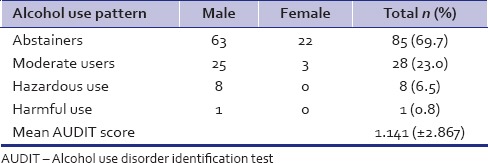

As shown in Table 2, most of the doctors (69.7%) did not drink alcohol in the past year, 28 (23%) were moderate drinkers (22 males and 6 females), 8 (6.6%) drank hazardously and one harmful drinker. None of the female respondents drank hazardously.

Table 2.

Alcohol consumption pattern of participants

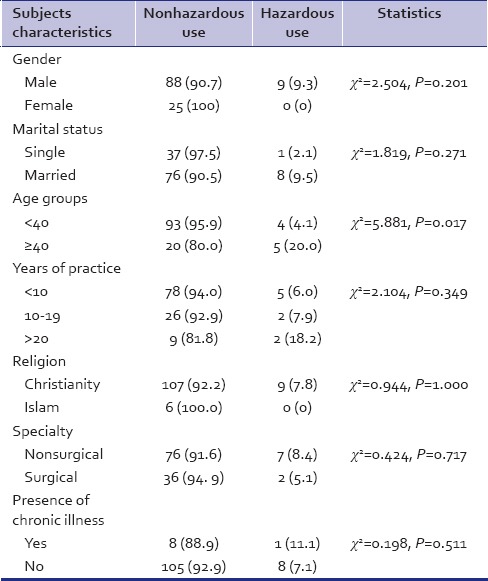

Table 3 shows the relationship between sample characteristics and hazardous alcohol use. Although all those who used alcohol hazardously were men, the relationship between gender and hazardous drinking was not statistically significant (P = 0.201). Similarly, there is no significant relationship between marital status, year of practice, religion, specialty of practice, the presence or absence of chronic illness, and hazardous alcohol use. Nonetheless, those who were older than 40 were more likely to use alcohol hazardously, and this was statistically significant (P = 0.017).

Table 3.

Subjects characteristics in relationship to hazardous alcohol use

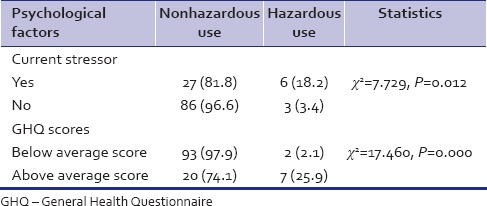

As can be seen in Table 4, of those who admitted experiencing current stressor (either relationship/marital, career, health or financial), a higher proportion (18.2%) were hazardous drinkers compared with 3.4% of those who were not experience any stressor and this was statistical significant (P = 0.012). Majority of the participants (66%) were experiencing stress in the area of their career (not in the table). Analysis of GHQ score in relation to hazardous alcohol use shown that a higher proportion of those who had GHQ score above average used alcohol hazardously. The association between GHQ scores and hazardous alcohol use was statistical significant (P = 0.000).

Table 4.

Psychological factors and hazardous alcohol use

DISCUSSION

Hospital doctors play a significant role in the prevention of harmful drinking in the society, however, their disposition to alcohol use will influence significantly this role. In Nigeria, however, there are limited studies that have looked at the pattern of alcohol use among hospital doctors. This study looked at the pattern of alcohol consumption and the predictors of hazardous drinking among hospital doctors. Alcohol use was low among doctors studied compared to other countries where the prevalence of alcohol use was close to 100%.[23,24] In our study, over 60% were abstainers with only approximately 7% either drinking hazardously or harmfully. This finding is in keeping with what was earlier reported by Issa et al. in another hospital in Nigeria[12] and Akvardar et al. in Turkey.[25] Issa et al.[12] reported that over 70% of doctors in their study were abstainers with only about 4% constituting hazardous and harmful drinkers. However, this is rather at variance with most findings in most Western countries.[3,6,26,27,28] For example, in a study by Rosta in Germany,[26] majority were moderate drinkers, only 9.5% were abstainers and with about 20% being hazardous drinkers similar to 18.5% reported by Joos et al.[29] in Belgium. Nonetheless, the proportion of doctors who were risky drinkers is lower compared with what obtained in the general population and patient population in Nigeria.[13,30] There are studies suggesting that risky drugs and alcohol use in practicing physicians are no greater than in the general public or other professionals[31,32,33] or even lower.[12,26] The lower rate of alcohol use reported among doctors may have resulted from their knowledge of negative consequences of alcohol, hence caution in the use of alcohol.

Several factors have been reported to influence hazardous drinking among doctors. In general, gender has been a recurrent factor influencing hazardous alcohol use generally.[34,35] In this study, none of the females used alcohol hazardously; nevertheless, there was no significant relationship between hazardous alcohol use and gender. Similarly, other studies have reported a lower rate of hazardous/harmful drinking among female doctors[12,28,29] and other population.[30] The lower number of females with alcohol use and the absence of female gender reported with hazardous alcohol use in this study may have been influenced by culture and religion. In Nigerian culture, where this study was carried out, it is largely permissive of men to drink alcohol rather than women. Again, Nigerian societies have some prejudice against women who drink alcohol especially those who consume it in excess. This may also affect the degree with which women report their alcohol use. Besides gender, age is an important factor that influences harmful alcohol use.[12,29,30,36] In this study, more respondents above 40 years had a higher rate of hazardous drinking compared to those below 40 years. In contrast, some authors have reported an association between younger age group and hazardous alcohol use.[12,27] Some other authors, however, had reported findings in keeping with our result.[26,29,37] Possible explanation for this may be that older doctors may have been exposed to longer periods of alcohol use resulting in an increment in quantity consumed over time. Other plausible explanation is the possibility that older doctors have more money and time at their disposal; further studies need to explore this.

Factors such as the length or years of practice, specialty in which a doctor practice and marital status did not predict hazardous drinking. Similar pattern of alcohol use was observed in both surgical and nonsurgical specialties as in a previous Nigerian study.[12] A study from Germany, however, reported that working in surgical specialties predict hazardous drinking.[26]

Some studies had reported a significant association between psychological distress and hazardous alcohol use in other population studied.[38,39,40] In this study, those who reported experiencing some level of stress were more likely to engage in hazardous drinking. Besides, those who scored above average on the GHQ score were also more likely to be hazardous drinkers compared to those who scored below the average score. Studies have shown an association between psychological or emotional distress and alcohol use,[30,38,39,40,41,42] albeit the complexity of establishing a definite causal relationship. Regardless of the relationship, people who abuse alcohol are prone to occupational, relational, and other health problems that make them vulnerable to developing psychological distress.[43] On the other hand, some people with certain psychological distress may engage in alcohol consumption as means of coping. Conversely, significantly increased psychological distress of abstainers compared to light/moderate drinkers was demonstrated in another study,[43,44,45] and this was partially explained by abstainers having poorer social relationships than light/moderate drinkers. The association between psychological distress and negative drinking consequences has been reported to be stronger among men than women.[46]

CONCLUSION

Hazardous drinking among hospital doctors appears to be essentially a problem of the male gender, especially among the older ones. Stress and other forms of psychological distress may play a significant role in predicting hazardous drinking among doctors. Therefore, efforts to reduce hazardous drinking among hospital doctors should focus on alleviating all forms of stress particularly career related.

Limitations of the study

The small sample size and the fact that the sample was drawn from just one center make it difficult to generalize the findings of this study to the general population of doctors in Nigeria. The strength of our findings lies in the fact that it adds to the body of knowledge about alcohol use among doctors in this environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge all the doctors who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babor T, Campbell R, Room R, Saunders J, editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. Lexicon of Alcohol and Drug Terms. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid MC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG. Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1681–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosta J. Prevalence of problem-related drinking among doctors: A review on representative samples. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank E, Rimer BK, Brogan D, Elon L. U.S. women physicians℉ personal and clinical breast cancer screening practices. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:791–801. doi: 10.1089/15246090050147763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosta J. Physicians’ interest in preventive work in relation to their attitudes and own drinking patterns: A comparison between Aarhus in Denmark and Mainz in Germany. Addict Biol. 2002;7:343. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison D, Chick J. Trends in alcoholism among male doctors in Scotland. Addiction. 1994;89:1613–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook D. Doctors neglect their own alcohol problems as well as those of their patients. BMJ. 1997;315:1299. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romelsjö A, Hasin D, Hilton M, Boström G, Diderichsen F, Haglund B, et al. The relationship between stressful working conditions and high alcohol consumption and severe alcohol problems in an urban general population. Br J Addict. 1992;87:1173–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray JD, Bhopal RS, White M. Developing a medical school alcohol policy. Med Educ. 1998;32:138–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett J, O’Donovan D. Substance misuse by doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2001;14:195–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohigian GM, Croughan JL, Sanders K, Evans ML, Bondurant R, Platt C. Substance abuse and dependence in physicians: The Missouri Physicians’ Health Program. South Med J. 1996;89:1078–80. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Issa BA, Yussuf AD, Abiodun OA, Olanrewaju GT, Kuranga TO. Hazardous alcohol use among doctors in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. West Afr J Med. 2012;31:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gureje O, Degenhardt L, Olley B, Uwakwe R, Udofia O, Wakil A, et al. A descriptive epidemiology of substance use and substance use disorders in Nigeria during the early 21 st century. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenna GA, Wood MD. Alcohol use by healthcare professionals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Benefit-cost analysis of brief physician advice with problem drinkers in primary care settings. Med Care. 2000;38:7–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: Health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2002;27:867–86. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raistrick D, Heather N, Godfrey C. London, UK: National Treatment Agency for Drug Abuse; 2006. Review of the Effectiveness of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption – II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adewuya AO. Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test (audit) as a screening tool for alcohol-related problems among Nigerian university students. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:575–7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg DP, Williams P. Windsor UK: NFER.Nelson; 1988. A User's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zulkefly NS, Baharudin R. Using the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) to assess the psychological health of Malaysian college students. Glob J Health Sci. 2010;2:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg DP, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J. Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med. 1998;28:915–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birch D, Ashton H, Kamali F. Alcohol, drinking, illicit drug use, and stress in junior house officers in north-east England. Lancet. 1998;352:785–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes PH, Brandenburg N, Baldwin DC, Jr, Storr CL, Williams KM, Anthony JC, et al. Prevalence of substance use among US physicians. JAMA. 1992;267:2333–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akvardar Y, Demiral Y, Ergor G, Ergor A. Substance use among medical students and physicians in a medical school in Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:502–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosta J. Hazardous alcohol use among hospital doctors in Germany. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:198–203. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roster J. Drinking patterns of doctors: A comparison between Aarhus in Denmark and Mainz in Germany. Drugs educ Prev Policy. 2002;9:367–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sebo P, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Goehring C, Künzi B, Bovier PA. Use of tobacco and alcohol by Swiss primary care physicians: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joos L, Glazemakers I, Dom G. Alcohol use and hazardous drinking among medical specialists. Eur Addict Res. 2013;19:89–97. doi: 10.1159/000341993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obadeji A, Oluwole LO, Dada MU, Ajiboye AS. Pattern and predictors of alcohol use disorders in a family practice in Nigeria. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:75–80. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.150824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weir E. Substance abuse among physicians. CMAJ. 2000;162:1730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAuliffe WE, Rohman M, Breer P, Wyshak G, Santangelo S, Magnuson E. Alcohol use and abuse in random samples of physicians and medical students. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:177–82. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGovern MP, Angres DH, Leon S. Characteristics of physicians presenting for assessment at a behavioral health center. J Addict Dis. 2000;19:59–73. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenfield S, Vertefuille J, McAlpine DD. Gender stratification and mental health: An exploration of dimensions of the self. Soc Psychol. 2000;63:208–23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John A, Barman A, Bal D, Chandy G, Samuel J, Thokchom M, et al. Hazardous alcohol use in rural southern India: Nature, prevalence and risk factors. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:123–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juntunen J, Asp S, Olkinuora M, Aärimaa M, Strid L, Kauttu K. Doctors’ drinking habits and consumption of alcohol. BMJ. 1988;297:951–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6654.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babalola E, Akinhanmi A, Ogunwale A. Who guards the guards: Drug use pattern among medical students in a Nigerian university. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4:397–403. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.133467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foulds J, Wells JE, Lacey C, Adamson S, Sellman JD, Mulder R. A comparison of alcohol measures as predictors of psychological distress in the New Zealand population. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2013;2:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balogun O, Koyanagi A, Stickley A, Gilmour S, Shibuya K. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in adolescents: A multi-country study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peltzer K. Depressive symptoms in relation to alcohol and tobacco use in South African university students. Psychol Rep. 2003;92:1097–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.3c.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Donnell K, Wardle J, Dantzer C, Steptoe A. Alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression in young adults from 20 countries. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:837–40. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucas N, Windsor TD, Caldwell TM, Rodgers B. Psychological distress in non-drinkers: Associations with previous heavy drinking and current social relationships. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:95–102. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchand A, Demers A, Durand P, Simard M. The moderating effect of alcohol intake on the relationship between work strains and psychological distress. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:419–27. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson S, Jacomb PA. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in abstainers, moderate drinkers and heavy drinkers. Addiction. 2000;95:1833–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9512183312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markman Geisner I, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addict Behav. 2004;29:843–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]