Abstract

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and disabling gastrointestinal problem that affects psychosocial functioning as well as the quality of life. This case study reports the utility of cognitive behavior therapy as a psychological intervention procedure in a chronic case of IBS. The use of psychological intervention was found to result in a reduction of anxiety; amelioration of the symptoms associated with IBS and improved functioning.

Keywords: Cognitive behavior therapy, exposure, irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, relapsing gastrointestinal disorder, characterized by recurring abdominal pain or discomfort associated with disturbed bowel habit or both, in the absence of structural abnormalities likely to account for these symptoms.[1] IBS is a common disorder that affects 5–11% of the population in most countries.[1]

Irritable Bowel Syndrome has been considered as a bio-psychosocial disorder that could results from the interaction of multiple systems including central nervous system, altered intestinal motility, increased sensitivity of the intestine and psychological factors.[2,3] Psychological factors such as stressful life events,[3] maladaptive behaviors,[3,4] and dysfunctional cognitions[5] can play a crucial role in IBS. “Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is a psychological intervention that can target both dysfunctional cognitions as well as maladaptive behaviors and is proven to be efficacious and durable treatment for anxiety, depression, obsessional fear, and rituals.”[6,7] It has also been a widely utilized psychological intervention in several chronic medical conditions including IBS.[1,4,8] Minimal-contact cognitive behavioral interventions have been examined for their applicability in the treatment of IBS.[8] A systematic review of minimal contact psychological treatments for symptom management in IBS has indicated that these show promise in the management of IBS symptoms and the effect sizes associated with interventions that use cognitive behavioral principles are large.[8] However, there is a paucity of studies on its effectiveness for IBS in Indian scenario.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first few case reports from India on the successful treatment of IBS using CBT.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old married male, educated up to 12th standard from middle socioeconomic status and working as a technical assistant presented to the outpatient department (OPD) of a multi-specialty hospital with complaints of frequent abdominal pain and disturbed bowel habits for the last 6 years. These pains would get exacerbated soon after eating and/or taking tea and reduce only after defecation. Moreover, these pains would become worse after eating dosa, chapatti, green vegetables, spicy foods, and using tea or coffee. In order to control pain and associated bowel habits, the patient started eating less (including reduced consumption of vegetables) and would avoid eating several items. He would also avoid going and eating in public places due to the fear of getting abdominal pain and needing to defecate. On a typical day, he would use toilet 5–7 times. Over time he started avoiding going to various places, both known or unknown and had stopped travelling due to fear of pain and leakage. Gradually, he became partially house bound with marked impairment in social functioning. He was able to continue working despite abdominal pain and frequent visits to toilet that significantly affected his occupational performance. He used to feel helpless and worried about his gastroenterological condition. There was no past history of physical, neurological or psychiatric illness. Personal history revealed ongoing stressors due to financial losses in the recent past and associated worsening of the symptoms. He had fairly good support from immediate family members including the spouse. There was no family history of psychiatric problems and premorbidly he was noted to be well adjusted. The patient was noted to have worries regarding his health issues and anxious affect during the mental status examination. He had been visiting the gastroenterologists and had been diagnosed to be suffering from IBS. He had been on pharmacological interventions as prescribed but had experienced no significant improvement for the past 5 years. He was then referred to the clinical psychologist for intervention. At the time of initiating psychological intervention, he was not on any medication. To begin with, he was doubtful about the utility of nonmedical intervention for his problems. However, he was cooperative for the same and his motivation for undergoing psychological intervention improved following socialization to the CBT model and building of therapeutic alliance.

The patient received eight session of CBT. The CBT consisted of socialization of the patient to CBT model, exposure and response prevention, cognitive reappraisal and relapse prevention. CBT for IBS is based on the understanding of the links between symptom related stimuli, experience of fear, and development of avoidance behaviors. Fear is known to alter motility and avoidance behaviors can result in long term aggravation of symptoms owing to increased psychological salience of symptoms as well as generalized stress.[9,10]

Initial phase

In the initial session, the patient was explained the rationale of CBT including principles underlying exposure and response prevention related procedures. A hierarchy of fears associated with consumption of different food items was prepared. It was noted that the patient was avoiding several kinds of food items on which there was no restriction as per the medical advice he had received. In other words, he was trying to follow an extremely restricted diet as self-prescribed. On occurrence of minor sensations of discomfort, he would use the toilet to experience some temporary relief. Either he passed a small quantity of stools or no stools during his visits to the toilet.

Middle phase

Therapist-assisted gradual exposure started with patient's cooperation in the OPD. He was encouraged to expose himself to stimuli associated with his fears. In this process, he was advised to consume food items lower on the hierarchy (least anxiety provoking) before the session and observe the sensations and associated distress while not using the toilet. Initially, he was anxious and fearful that he might need to use the toilet or would not be able to control. However, proper education about exposure and response prevention helped in motivating him to tolerate the distress and thereby experience a reduction in his anxiety toward the end of the exposure sessions. This step was followed subsequently for food items somewhat higher on the hierarchy. Though he reported tightness in the abdomen during the exposure sessions, he was able to tolerate it without using the toilet. After three sessions, he become comfortable with the process and reported a significant reduction in his abdominal sensations. In the next three sessions, the patient was advised to eat normal food before coming to the sessions for therapist-assisted exposure. After the fourth session, he was able to practice such exercises at home with minimal pain. After 6 sessions, he was able to tolerate minor pain/discomfort without using the toilet and his bowel habits improved significantly (one or twice in a day).

Termination phase

At this juncture, he was encouraged to identify catastrophic thoughts and develop alternative more realistic thoughts to help him cope with IBS. This included a discussion of his avoidance of social functions/travel and how this avoidance was providing temporary relief and yet strengthening the fears and interfering with his quality of life. Gradually, he started going out and attending social functions which he had avoided since the past few years. He expressed satisfaction about regaining his independence and his quality of life improved dramatically according to his self-report. He was explained about a relapse of the symptoms and ways to deal with the same.

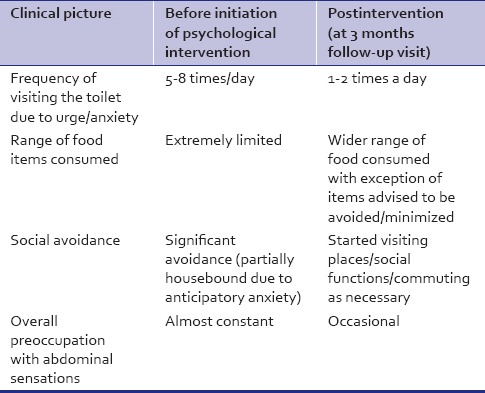

At 9 months follow-up, these gains were maintained and the patient was satisfied with the outcome [Table 1].

Table 1.

Depiction of changes in clinical status (as per self-reports)

DISCUSSION

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is a chronic and disabling condition that can affects psychological and social functioning. It is a common disorder that generates significant health care costs.[1] Medical management of this condition is often unsatisfactory.[4] However, psychological treatment has been found effective for IBS.[1,4,8] It has been suggested that patients with IBS develop maladaptive behaviors regarding eating and defecation that reinforce the magnitude of symptoms and their impact on quality of life.[4] Dysfunctional cognitions are also known to affect physical and mental quality of life as well as symptom severity.[5] These maladaptive behaviors and dysfunctional cognitions could be addressed using CBT. In the case discussed here, we used CBT as a primary intervention. Our results showed favorable and promising results of CBT in IBS. Use of behavioral and cognitive techniques could provide an opportunity to modify erroneous learning and decrease the experience of anxiety as well as IBS symptoms. The present study indicates that CBT could be an effective treatment for IBS, especially in cases wherein there is a significant element of anxiety and avoidance behaviors. This case study is in line with other studies which show that psychological treatments are effective in treating IBS.[1,4,8] Further research is needed to understand the factors that indicate a good response to psychological intervention in general and CBT in particular for IBS. The role of nonspecific factors (e.g., alliance with the therapist, hope building and support etc.) need to be disentangled from the contribution of CBT specific techniques in studies involving controlled trials. Furthermore, the role of indigenous beliefs regarding diets in maintenance of avoidance behaviors, mechanisms of change through CBT for IBS as well as the long term maintenance of gains following therapy are issues that require attention of researchers.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: Mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porcelli P. Psychological abnormalities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surdea-Blaga T, Baban A, Dumitrascu DL. Psychosocial determinants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:616–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayee B, Forgacs I. Psychological approach to managing irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2007;334:1105–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39199.679236.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thijssen AY, Jonkers DM, Leue C, van der Veek PP, Vidakovic-Vukic M, van Rood YR, et al. Dysfunctional cognitions, anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e236–41. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181eed5d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franklin ME, Foa EB. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:229–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pajak R, Lackner J, Kamboj SK. A systematic review of minimal-contact psychological treatments for symptom management in irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, Bolus R, Naliboff BD. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: Further validation of the visceral sensitivity index. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:89–98. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e2f24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almy TP, Tulin M. Alterations in colonic function in man under stress; experimental production of changes simulating the irritable colon. Gastroenterology. 1947;8:616–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]