Abstract

Purpose

Apply manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) to assess ion channel activity and structure of retinas from mice subject to light-induced retinal degeneration treated with prophylactic agents.

Methods

Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice with and without prophylactic retinylamine (Ret-NH2) treatment were illuminated with strong light. Manganese-enhanced MRI was used to image the retina 2 hours after intravitreous injection of MnCl2 into one eye. Contrast-enhanced MRIs of the retina and vitreous humor in each experimental group were assessed and correlated with the treatment. Findings were compared with standard structural and functional assessments of the retina by optical coherence tomography (OCT), histology, and electroretinography (ERG).

Results

Manganese-enhanced MRI contrast in the retina was high in nonilluminated and illuminated Ret-NH2–treated mice, whereas no enhancement was evident in the retina of the light-illuminated mice without Ret-NH2 treatment (P < 0.0005). A relatively high signal enhancement was also observed in the vitreous humor of mice treated with Ret-NH2. Strong MEMRI signal enhancement in the retinas of mice treated with retinylamine was correlated with their structural integrity and function evidenced by OCT, histology, and a strong ERG light response.

Conclusions

Manganese-enhanced MRI has the potential to assess the response of the retina to prophylactic treatment based on the measurement of ion channel activity. This approach could be used as a complementary tool in preclinical development of new prophylactic therapies for retinopathies.

Keywords: manganese-enhanced MRI, retinylamine, retinal degeneration, efficacy evaluation

Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a useful imaging modality to assess the efficacy of therapies in preventing retinal degeneration based on ion channel activities.

Retinal degenerative diseases are a leading cause of blindness.1 In healthy individuals, the retinoid cycle mediates the light response in photoreceptor cells, whereby photoisomerization of the cis-retinal chromophore initiates a cycle of enzymatic activities to transduce the signal and regenerate the original chromophore.2 Retinal degeneration, at least in part, is attributed to accumulation of toxic byproducts of the retinoid cycle such as all-trans-retinal (atRAL) and A2E-like derivatives that induce apoptosis of photoreceptor cells.3 Primary amines, including retinylamine, have been shown to modulate the visual cycle and prevent excessive accumulation of atRAL.4–6 Studies in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice, a light-induced retinal degeneration model, have demonstrated the efficacy of retinylamine to prophylactically preserve photoreceptor and RPE cells and prevent vision loss.7,8

The retinoid cycle relies on Ca2+ channel activity to transduce light-responsive enzymatic activity into electrical signaling.9,10 Regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration is critical for polarization of the cell, activation of voltage-gated ion channels, and adaptation of photoreceptor cells to retain responsiveness in different conditions of ambient lighting. In retinal degeneration, photoreceptor cell death results in a loss of capacity for Ca2+ signaling. Thus, when these cells are protected from degeneration by prophylactic treatment with retinylamine, we decided to assess Ca2+-signaling activity in response to this intervention.

Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) enables direct spatial visualization of Ca2+ channel activity in vivo. In MEMRI, paramagnetic Mn2+ ions are used as T1 contrast agents to image the activity of Ca2+ channels.11,12 In excitable cells, such as neurons and cardiac cells, Mn2+ has been shown to be taken up by active calcium signaling pathways, including voltage-gated channels. Mn2+ then is retained in these cells with a long half-life due to its slow cellular efflux.13,14 Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is uniquely suited to image neural activity with the high spatial resolution and soft tissue contrast characteristic of MRI.

Manganese-enhanced MRI has been used to study activity in various sensory pathways of the brain, including the auditory tract15 and the olfactory response.16 This technique holds particular appeal to assess retinal health because Mn2+ administration in the eyes is nontoxic at low doses that still fall within detection limits for contrast enhancement.17–19 In the visual system, MEMRI has been employed to study phototransduction under differing conditions20,21 and evaluated in disease models such as glaucoma,22,23 optic nerve crush,24 and diabetic retinopathy.25 With its ability to image anatomical structures and signaling activity simultaneously, we expect that MEMRI will be an effective method to assess the treatment response by measuring Ca2+ signaling activities in the retina.

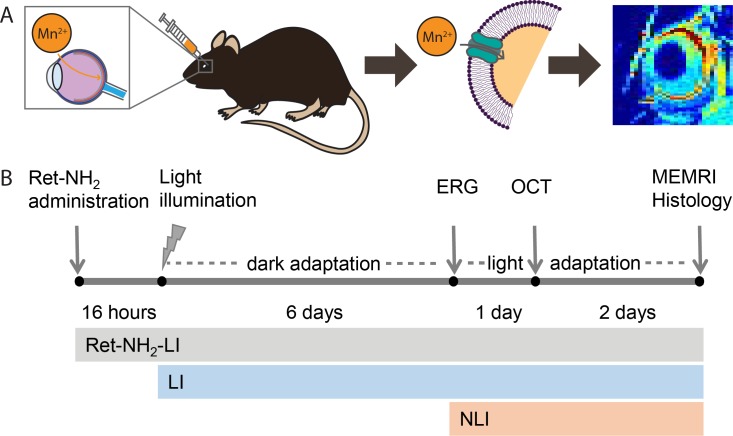

In this work, we investigated the use of MEMRI in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice to evaluate intense light-induced retinal degeneration and its response to prophylactic treatment with retinylamine, a potent retinoid cycle modulator, based on changes in Ca2+ channel activity in the retina. Thus, we evaluated the ability of MEMRI to assess the structure and function of healthy, drug-treated, and fully degenerated retinas in these mutant mice according to the experimental time line shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Use of MEMRI to assess retinal integrity and function. Mn2+ was injected directly into the vitreous humor of the right eye. (A) Actively signaling photoreceptor cells take up and retain Mn2+ through voltage-gated calcium channels. This phenomenon is detected as a bright signal in the retina on T1-weighted MRI. (B) Treatment and experimental schedule for drug-treated, illuminated Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice (Ret-NH2-LI), LI mice, and NLI mice. Retinylamine-treated animals were protected from rapid retinal degeneration due to intense light exposure, whereas untreated LI animals underwent this degeneration. Nonilluminated animals did not undergo retinal degeneration and served as healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment

Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice were generated as previously described.6 All mice used of either sex in this study were homozygous for the Leu450 allele of Rpe65 as determined by a genotyping protocol described earlier,26 and the mice were also free of Crb1/rd8 Pde6/rd1 mutations.27 This mouse model is light-sensitive, and retinal degeneration can be accelerated by intense light exposure.3,28,29 Animals were housed and bred in the Animal Resource Center at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU; Cleveland, OH, USA) and cared for according to an approved protocol by the CWRU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in compliance with recommendations from the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

The drug treatment, light illumination (LI), and evaluation schedule is shown in Figure 1B. Untreated, LI (n = 5) and treated, LI (Ret-NH2-LI, n = 5) mice were illuminated with 10,000 lux yellow light for 60 minutes while contained in a white bucket with their pupils dilated with 1% tropicamide. Animals were housed in the dark for 6 days prior to ERG. Animals were then kept in conditions of ambient lighting for optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and Mn2+ injection. Nonilluminated (NLI, n = 6) mice not exposed to light served as healthy controls. Retinylamine was obtained as previously described6 and administered to the treatment group by oral gavage 16 hours prior to light illumination (50 mg/kg dissolved in 100 μL 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) in vegetable oil).

Optical Coherence Tomography

Ultra-high resolution spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT Envisu C2200; Bioptigen, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to image the structure of mouse retinas in vivo. Animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail (15 μL/g body weight) comprised of ketamine (6 mg/mL) and xylazine (0.44 mg/mL) in PBS buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 100 mM NaCl). Pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide for imaging. Four images acquired in the B-scan mode were averaged to construct each final SD-OCT image. The outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was quantified with Bioptigen software at 150, 300, and 450 μm from the ocular nerve head in the temporal-nasal and superior-inferior directions.

Electroretinography

Electroretinograms were acquired as previously described30 24 hours after OCT imaging to allow the animals sufficient time to recover from anesthesia. Mice were anesthetized by the same procedure used for OCT imaging and experiments were performed in a dark room. Three electrodes were placed on the animal: a contact lens electrode on the eye, a reference electrode underneath the skin between the ears, and a ground electrode underneath the skin of the tail. Electroretinograms were recorded with the universal electrophysiologic system UTAS E-3000 (LKC Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Light intensity calibrated by the manufacturer was computer-controlled. Mice were placed in a Ganzfeld dome, and scotopic responses to flash stimuli were obtained from both eyes simultaneously.

Manganese-Enhanced MRI

Mn2+ was administered by intravitreous injection into the right eye of the mouse in ambient lighting conditions (2.4 μL, 5 mM MnCl2 per mouse; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). The noninjected left eye was used as a contralateral control. Mice were anesthetized by the same procedure used for OCT imaging and allowed to wake up before being reanesthetized with 2% isoflurane immediately prior to MRI experiments. Magnetic resonance images were acquired on a preclinical 7T scanner (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a volume coil. A series of scouting scans was performed to locate the eyes in the scanner. Two hours after injection of MnCl2, a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) scan was performed with a two-dimensional (2D) coronal multislice, multiecho spin echo acquisition (TR = 400 ms, TE = 10.6 ms, FOV = 2.5 × 2.5 cm, resolution = 98 × 195 μm, number of averages = 16, total imaging time = 14 minutes).

Histology

Mice were euthanized immediately following MRI experiments. Eye cups were harvested, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and embedded and frozen in OCT compound (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA, USA). Slides, 12-μm thick, were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Data/Statistical Analysis

Manganese-enhanced MRI images and ERG traces were visualized and analyzed with MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). Signal enhancement in MRI was quantified as the percentage change of signal between the contrast-injected eye and the contralateral control. The retina was delineated by manually-defined regions of interest. A-waves and b-waves were calculated from ERG traces using a custom MATLAB script. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with a P value of less than or equal to 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Structural Evaluation of the Retina

Representative OCT images of the retina of Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice in NLI, retinylamine-treated (Ret-NH2-LI) and/or LI groups are shown in Figure 2A. The treatment with Ret-NH2 protected the retina from light-induced degeneration, while light illumination destroyed the retinas of the mice without the treatment. Mice in the Ret-NH2-LI group retained an intact retina structure as did those without illumination. Histologic analyses of the retina were in good agreement with the OCT results. An intact retinal structure with a thick ONL was present in NLI and retinylamine-treated animals (Fig. 2B), whereas substantial thinning of the ONL was observed in untreated LI mice. The ONL, inner and outer segment, and RPE layers containing the photoreceptor cell layers were nearly absent in these animals, and appeared fully detached from the choroid.

Figure 2.

Structural evaluations of retinal degeneration. (A) Representative OCT images of the retinas of the mice with no treatment and NLI, with retinylamine treatment and light illumination (Ret-NH2-LI), and with light illumination and no treatment (LI). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the eye cups. (C) Outer nuclear layer thickness quantified by OCT in the nasal-temporal (top) and superior-inferior (bottom) directions as a function of distance from the optic nerve head in the NLI (black squares), Ret-NH2-LI (red circles), and LI (blue triangles) mice. Error bars represent ± SD. Scale bars: 50 μm.

The thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) was measured from OCT images to assess the extent of retinal degradation and therapeutic efficacy of Ret-NH2 (Fig. 2C). The ONL thickness of mice treated with retinylamine was similar to that of NLI animals, indicating that Ret-NH2 treatment protected the retina from degeneration. Quantitative measurements of ONL thickness were slightly higher in retinylamine-treated animals than in NLI controls but these differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). By comparison, a distinct ONL could not be visualized in LI mice. Rather, a dark band was present between the outer plexiform layer and the choroid, indicative of retinal detachment from the RPE layer at numerous locations (Fig. 2B). The thickness of the ONL in the untreated LI retinas could not be quantified (Figs. 2A, 2B) and was 0 for all distances from the optic nerve head (Fig. 2C).

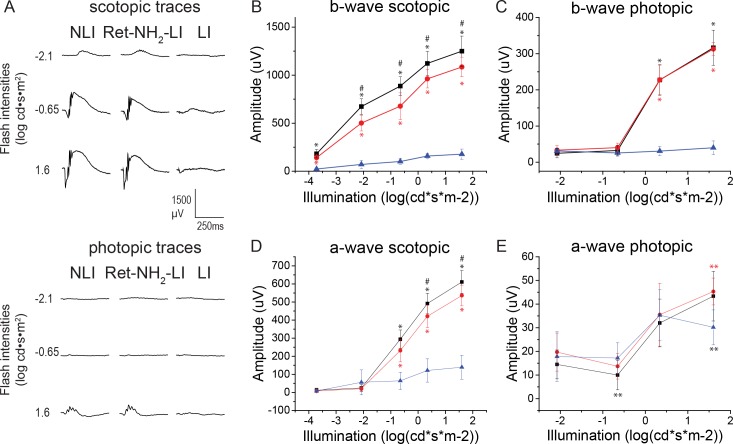

ERG Measurements of Retinal Function

Electroretinograms revealed retinal function in response to Ret-NH2 treatment with representative traces shown in Figure 3A. In LI untreated mice only a minimal response was detected. Electroretinogram responses in the treatment group and NLI mice exhibited a light response under all scotopic and most photopic conditions, with higher b-waves in NLI controls than in the drug-treatment group (Figs. 3B–E). Under most stimulus conditions, responses in the NLI and Ret-NH2-LI animals were markedly higher than in the LI animals (P < 0.0005).

Figure 3.

Electroretinogram analysis of retinal function for NLI (black squares), Ret-NH2-LI (red circles), and LI (blue triangles) mice. (A) Representative traces of flash responses under scotopic conditions. (B, C) Calculated b-waves recorded under scotopic and photopic conditions, respectively. (D, E) Calculated a-waves recorded under scotopic and photopic conditions, respectively. Error bars represent ± SD. #P < 0.05 versus Ret-NH2-LI. *P < 0.05 versus LI. **P < 0.0005 versus LI.

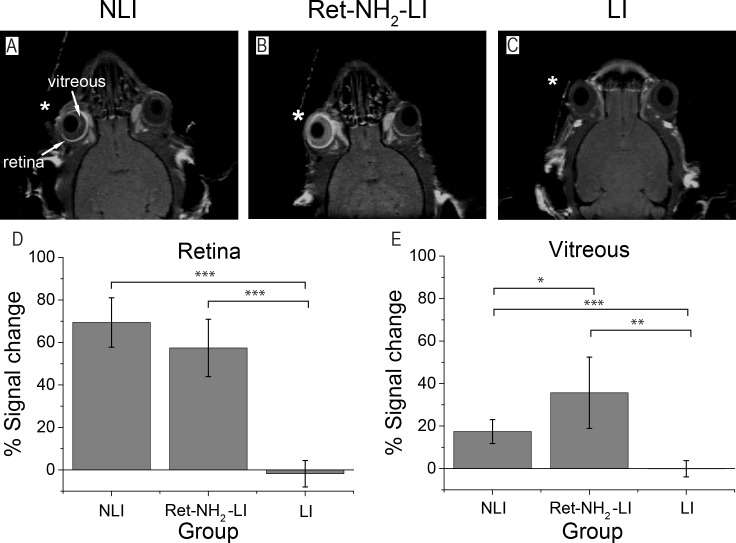

MEMRI of the Retina

Two-dimensional T1-weighted MEMRI images were successfully acquired in the NLI, Ret-NH2-LI, and LI groups 2 hours following intravitreous injection of MnCl2 into the right eye (Figs. 4A–C). In the drug-treated mice, the signal in the retina of the injected eye was enhanced. The signal in the retina also was enhanced in the NLI controls, whereas in LI mice without Ret-NH2 treatment, signal in the retina remained unchanged with no Mn2+ enhancement. Manganese-enhanced MRI enhancement in the retina was quantified by the percent change of signal in the retina of the injected eye relative to that of the contralateral control (Fig. 4D). Contrast enhancement due to the Mn2+ injection was statistically significant for NLI and retinylamine-treated mice compared with the LI mice. Clearance of Mn2+ from the injection site was assessed by MRI signal enhancement in the vitreous humor and was quantified according to the same procedure used for the retina. The vitreous signal was highest after retinylamine treatment, lower in NLI mice, and negligible in untreated LI controls (Fig. 4E). The higher signal in the vitreous of the retinylamine-treated animals suggests a slower transport of Mn2+ out of the eyes relative to the other experimental groups.

Figure 4.

(A–C) Representative coronal MEMRI images of mouse retina 2 hours after intravitreous injection of Mn2+ to the right eye (*). The left eye was not injected as a contralateral control. (D, E) Average percentage change of MEMRI signal in the retina and vitreous humor of Mn2+-injected eyes relative to contralateral controls, respectively (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0005). Error bars represent ± SD of the means (n = 5).

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated the use of MEMRI to assess the efficacy of prophylactic treatment with retinylamine by measuring Ca2+ channel activity in the retina. Following intravitreous injection of Mn2+, healthy retinas appeared bright in T1-weighted MRIs, while damaged retinas appeared dark. The health of the retina for each group was confirmed with OCT, histology, and ERG, standard techniques currently employed to assess the extent of retinal degeneration. These results are consistent with literature reports of retinal degeneration and protection in this model.3,5,7,8 In Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice, OCT and histology demonstrated that retinal structures were intact in the NLI and retinylamine-treated mice, whereas clear signs of degradation were observed in untreated, LI mice. Similarly, ERG demonstrated full functional responsiveness to light in healthy animals but limited responsiveness in untreated, LI mice. The MEMRI results reported here accurately stratified the mice into healthy and retina-degenerated groups, and validated the use of MEMRI to evaluate the efficacy of retinylamine for treatment of the latter.

The Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mouse shows a phenotype similar to that of human Stargardt disease and AMD.3,29,31 Moreover, mutations of ABCA4 are associated with both diseases.32,33 Accelerated retinal degeneration following exposure to intense light permits an examination of retinal pathology and therapeutic effects within a short period of time.6–8,34,35 In previous work, it was demonstrated that the primary cause of retinal degeneration in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice is a delay in clearance of all-trans-retinal after light perception,3 such that buildup of atRAL resulted in photoreceptor cell death characteristic of retinal degenerative diseases in humans. To prevent the toxic effects of atRAL, a visual cycle modulator, retinylamine, was shown to decrease the production of atRAL, allowing its clearance and preventing photoreceptor damage in both wild-type4,36 and Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice.3

Based on Ca2+ signaling in retinal photoreceptor cells, MEMRI was used in this work to study the effects of retinylamine in protecting against retinal degeneration in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice. In NLI and retinylamine-treated mice, the bright MEMRI signal reflected normal ion channel activity in the structurally and functionally intact photoreceptor cells that was corroborated by OCT and ERG. The absence of MEMRI signal enhancement observed in this case indicates that ion channel activity is deficient in severely degenerated retinas, and further suggests that the primary source of Ca2+ activity in the retina comes directly from the photoreceptor cells and not from other cell types in the retina.

Our results are in agreement with previous MEMRI studies of retinal activity. Using custom-built surface coils, investigators localized Mn2+ uptake to nuclear layers of the retina and the choroid vasculature.18 Furthermore, Mn2+ administration under different intensities of ambient light have shown that Mn2+ uptake in the retina parallels the opening of cGMP-gated ion channels during light illumination.20,21 When these cGMP-gated channels had deteriorated, as was the case in retinal degeneration here, MEMRI does not produce any signal enhancement.

In addition to imaging retinal activity, we also monitored the clearance of Mn2+ contrast out of the vitreous humor. Two hours after Mn2+ injection, signal enhancement in the vitreous humor was significantly higher in the retinylamine-treated animals than in healthy mice and NLI controls, indicating a slower washout of the contrast media. This result, which was not attainable by OCT or ERG, suggests that despite protection by retinylamine, treated eyes can function differently than in normal animals, as transport is restricted. This change could prove an advantage for retinylamine treatment, as therapeutic concentrations of this drug could be retained for longer periods to prolong efficacy. Future studies will build upon this insight gained from MEMRI to investigate how mechanisms of ocular transport are affected by retinylamine.

In future work, we will expand our imaging protocol to study other components of the visual system in addition to the retina. Using a volume coil with a large field of view, we can modify our MRI sequence to perform 3D volume imaging of the whole brain, including the optic nerve tract. This extension will allow the use of imaging to explore the full effects and mechanisms of drugs on the visual system. The same methodology will also be applied to evaluate other therapeutics for retinopathies and animal models of retinal dysfunction.

Conclusions

Manganese-enhanced MRI is an effective imaging modality for evaluating the function of the visual cycle. Based on Ca2+ channel activity, this technique can be used in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice to assess retinal degeneration and the prophylactic therapeutic efficacy of retinylamine. Manganese-enhanced MRI complements the established methods currently employed for this purpose and could be expanded to explore and understand the effects and mechanisms of new therapeutics under drug development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ed Wu, PhD, of the University of Hong Kong for his valuable suggestions. Supported by grants from the Interdisciplinary Biomedical Imaging Training Program, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) T32EB007509 administered by the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Case Western Reserve University. This work was supported in part by funding from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health Grant R24EY0211260.

Disclosure: R.M. Schur, None; L. Sheng, None; B. Sahu, None; G. Yu, None; S. Gao, None; X. Yu, None; A. Maeda, None; K. Palczewski, None; Z.-R. Lu, None

References

- 1. Friedman DS,, O'Colmain BJ,, Muñoz B,, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Travis GH,, Golczak M,, Moise AR,, Palczewski K. Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007; 47: 469–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maeda A,, Maeda T,, Golczak M,, Palczewski K. Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 26684–26693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Golczak M,, Kuksa V,, Maeda T,, Moise AR,, Palczewski K. Positively charged retinoids are potent and selective inhibitors of the trans-cis isomerization in the retinoid (visual) cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102: 8162–8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maeda A,, Maeda T,, Golczak M,, et al. Effects of potent inhibitors of the retinoid cycle on visual function and photoreceptor protection from light damage in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2006; 70: 1220–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maeda A,, Golczak M,, Chen Y,, et al. Primary amines protect against retinal degeneration in mouse models of retinopathies. Nat Chem Biol. 2012; 8: 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu G,, Wu X,, Ayat N,, et al. Retinylamine conjugate provides prolonged protection against retinal degeneration in mice. Biomacromolecules. 2014; 15: 4570–4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puntel A,, Maeda A,, Golczak M,, et al. Prolonged prevention of retinal degeneration with retinylamine loaded nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2015; 44: 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palczewski K,, Polans AS,, Baehr W,, Ames JB. Ca2+-binding proteins in the retina: structure, function, and the etiology of human visual diseases. BioEssays. 2000; 22: 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akopian A,, Witkovsky P. Calcium and retinal function. Mol Neurobiol. 2002; 25: 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin Y,, Koretsky A. Manganese ion enhances T1-weighted MRI during brain activation: an approach to direct imaging of brain function. Magn Reson Med. 1997; 38: 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pautler RG. In vivo trans-synaptic tract-tracing utilizing manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI). NMR Biomed. 2004; 17: 595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drapeau P,, Nachshen DA. Manganese fluxes and manganese-dependent neurotransmitter release in presynaptic nerve endings isolated from rat brain. J Physiol. 1984; 348: 493–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rasgado-Flores H,, Sanchez-Armass S,, Blaustein MP,, Nachshen DA. Strontium, barium, and manganese metabolism in isolated presynaptic nerve terminals. Am J Physiol. 1987; 252 (6 pt 1): C604–C610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu X,, Wadghiri YZ,, Sanes DH,, Turnbull DH. In vivo auditory brain mapping in mice with Mn-enhanced MRI. Nat Neurosci. 2005; 8: 961–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pautler RG,, Koretsky AP. Tracing odor-induced activation in the olfactory bulbs of mice using manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2002; 16: 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thuen M,, Berry M,, Pedersen TB,, et al. Manganese-enhanced MRI of the rat visual pathway: acute neural toxicity, contrast enhancement, axon resolution, axonal transport, and clearance of Mn(2+). J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008; 28: 855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo L,, Xu H,, Li Y,, et al. Manganese-enhanced MRI optic nerve tracking: effect of intravitreal manganese dose on retinal toxicity. NMR Biomed. 2012; 25: 1360–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin T-H,, Chiang C-W,, Trinkaus K,, et al. (MEMRI) via topical loading of Mn(2+) significantly impairs mouse visual acuity: a comparison with intravitreal injection. NMR Biomed. 2014; 27: 390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berkowitz BA,, Roberts R,, Goebel DJ,, Luan H. Noninvasive and simultaneous imaging of layer-specific retinal functional adaptation by manganese-enhanced MRI. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 2668–2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De La Garza BH,, Li G,, Shih Y-YI,, Duong TQ. Layer-specific manganese-enhanced MRI of the retina in light and dark adaptation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 4352–4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chan KC,, Fu Q,, Hui ES,, So K,, Wu EX. Evaluation of the retina and optic nerve in a rat model of chronic glaucoma using in vivo manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2008; 40: 1166–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calkins DJ,, Horner PJ,, Roberts R,, Gradianu M,, Berkowitz B. Manganese-enhanced MRI of the DBA/2J mouse model of hereditary glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 5083–5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thuen M,, Olsen O,, Berry M,, et al. Combination of Mn(2+)-enhanced and diffusion tensor MR imaging gives complementary information about injury and regeneration in the adult rat optic nerve. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009; 29: 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berkowitz BA,, Gradianu M,, Bissig D,, Kern TS,, Roberts R. Retinal ion regulation in a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy: natural history and the effect of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase overexpression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 2351–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Danciger M,, Lyon J,, Worrill D,, et al. New retinal light damage QTL in mice with the light-sensitive RPE65 LEU variant. Mamm Genome. 2004; 15: 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mattapallil MJ,, Wawrousek EF,, Chan CC,, et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2921–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maeda A,, Maeda T,, Golczak M,, et al. Involvement of all-trans-retinal in acute light-induced retinopathy of mice. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 15173–15183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kohno H,, Chen Y,, Kevany BM,, et al. Photoreceptor proteins initiate microglial activation via toll-like receptor 4 in retinal degeneration mediated by all-trans-retinal. J Biol Chem. 2013; 288: 15326–15341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeda T,, Van Hooser JP,, Driessen CAGG,, Filipek S,, Janssen JJM,, Palczewski K. Evaluation of the role of the retinal G protein-coupled receptor (RGR) in the vertebrate retina in vivo. J Neurochem. 2003; 85: 944–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maeda A,, Golczak M,, Maeda T,, Palczewski K. Limited roles of Rdh8, Rdh12, and Abca4 in all-trans-retinal clearance in mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5435–5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allikmets R,, Singh N,, Sun H,, et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997; 15: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Allikmets R,, Seddon JM,, Lewis RA,, et al. Mutation of the Stargardt disease gene (ABCR) in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 1997; 277: 1805–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y,, Palczewska G,, Mustafi D,, et al. Systems pharmacology identifies drug targets for Stargardt disease-associated retinal degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013; 123: 5119–5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Y,, Okano K,, Maeda T,, et al. Mechanism of all-trans-retinal toxicity with implications for stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287: 5059–5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maeda A,, Maeda T,, Golczak M,, et al. Effects of potent inhibitors of the retinoid cycle on visual function and photoreceptor protection from light damage in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2006; 70: 1220–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]