Abstract

Patient: Female, 76

Final Diagnosis: Peritoneal mesothelioma epithelioid type

Symptoms: Alternating bowel habits • ascites • small bowel obstruction • weight loss

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Exploratory laparotomy • excisional biopsy

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Peritoneal mesothelioma is a rare malignancy that affects the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum. The peritoneum is the second most common site of mesothelium affected following the pleura. The aggressive nature and vague presentation pose many obstacles in not only diagnosis but also the treatment of patients with this disease.

Case Report:

We present a case of a 76-year-old woman who presented with small bowel obstruction secondary to carcinomatosis secondary to primary peritoneal mesothelioma. The patient had multiple risk factors with asbestos exposure and prior therapeutic radiation.

Conclusions:

We discuss the highly varied and elusive presentation of peritoneal mesothelioma. Cumulative asbestos exposure, either directly or indirectly, remains the leading cause of mesothelioma. However, there are other non-asbestos etiologies. Small bowel obstruction often is a late-presenting symptom of widespread tumor burden. A concise review of the current diagnostic and surgical treatment of primary peritoneal mesothelioma demonstrates that early diagnosis and implementation remains vital.

MeSH Keywords: Mesothelioma, Peritoneal Cavity, Intestinal Obstruction

Background

Mesotheliomas are rare and aggressive neoplasms that arise from the surface of serosal cells of pleura, peritoneum, pericardium, and tunica vaginalis testes [1]. The diagnosis and treatment of peritoneal mesothelioma is often delayed due to the non-specific clinical symptoms and varied presentations. Commonly, peritoneal mesothelioma is misdiagnosed as another neoplasm originating from other abdominal organs, notably adenocarcinoma of the ovary and other gynecological manifestations [2]. We present the case of a 76-year-old female patient with small bowel obstruction secondary to intra-abdominal mesothelioma with carcinomatosis.

Case Report

A 76-year-old woman presented to the hospital with complaints of nausea, bilious vomiting, abdominal pain, and alternating cycles of diarrhea and constipation. On further review of systems she admitted to poor oral intake and progressive weight loss of 40 pounds. Her past medical history was significant for cervical and uterine cancer, pleural effusions, radiation enteritis, and recurrent ascites after a non-diagnostic paracentesis. The patient recalled being exposed to asbestos at home; her husband was a longtime worker in the shipyard industry. Physical examination revealed a distended abdomen with minimal tenderness to palpation and bilateral lower extremity edema.

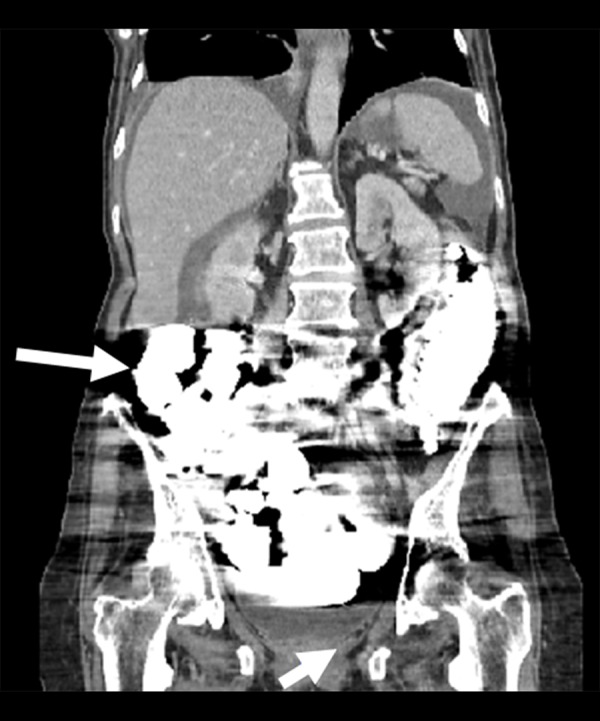

Pertinent laboratory studies included sodium of 125 mEq/L, hemoglobin of 9 g/dL, white blood cell count of 15.4×109/L, as well as a platelet count of 676×109/L. Tumor markers included a CA 125 of 4094.4 U/mL and CEA of <0.50ng/mL. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed ascites, stomach and small bowel wall thickening, and dilation of multiple small bowel loops (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen with dilated loops of small bowel and retained contrast. There is also thickened wall of the lower rectum and ascitic fluid throughout.

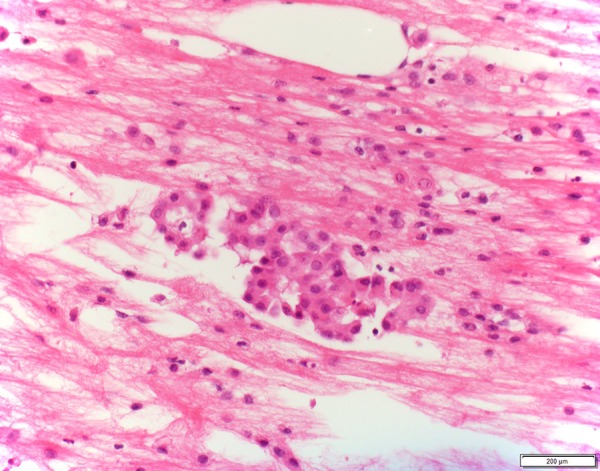

Nasogastric tube decompression was attempted as conservative management for the small bowel obstruction. The patient underwent a thoracentesis of a right pleural effusion, which exhibited atypical mesothelial cells. Concurrently, a paracentesis was performed and demonstrated similar pathological findings (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cytology specimen of peritoneal effusion shows atypical mesothelial cells in papillary architecture.

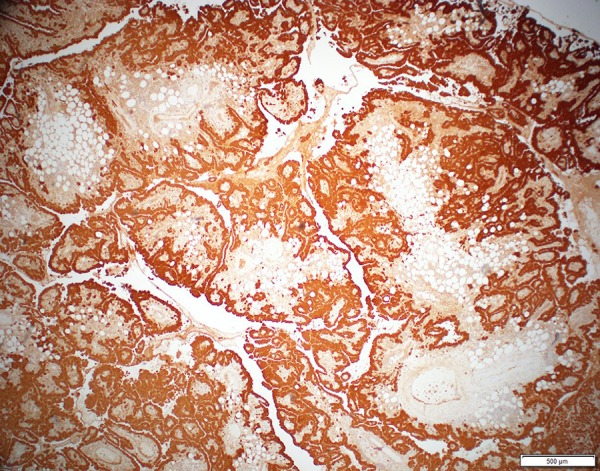

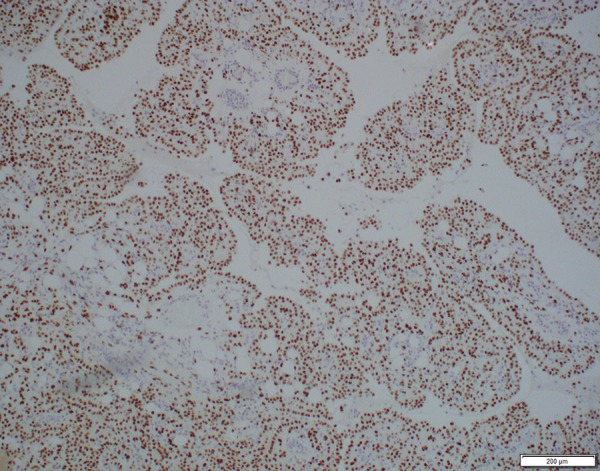

Immunohistochemical stains demonstrated cells positive for calretinin, CK5/6, CK7, WT1 and negative for CK20, CEA, MOC-31(Figures 3–5). After 2 days of conservative management with nasogastric tube, there was no resolution of the small bowel obstruction, with persistent symptoms of nausea and abdominal distention. The patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. Upon exploration, diffuse ascites was encountered throughout the abdomen.

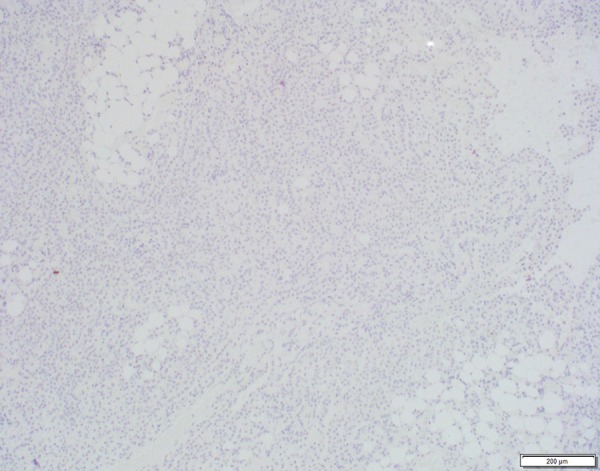

Figure 3.

Mesothelial origin of the cells is demonstrated by positive immunohistochemical stain of calretinin.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical stains of CK5/6 and WT-1 are also positive, confirming the mesothelial origin.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical stain of CEA commonly used to differentiate mesothelioma (negative) from adenocarcinoma (positive).

Persistence of the small bowel obstruction was secondary to multiple areas of carcinomatosis and peritoneal metastasis. This was managed conservatively without major surgical debulking. During the laparotomy, an excisional biopsy was performed of the pelvic soft tissue and omentum (Figure 6). Final pathologic examination supported the diagnosis of primary epithelioid-type mesothelioma (Figure 7). Following the diagnosis the patient refused treatment and opted for palliative care.

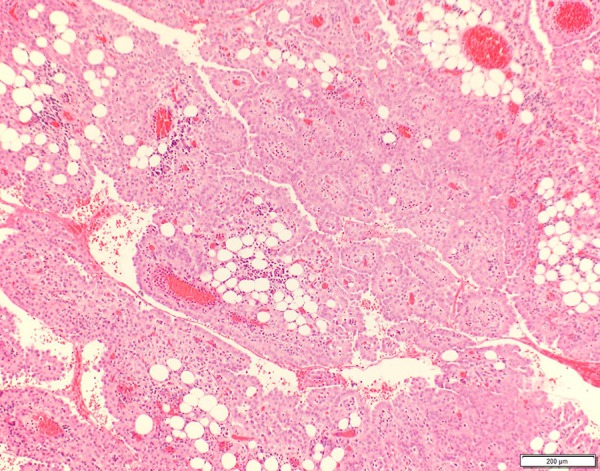

Figure 6.

Surgical excisional biopsy demonstrates exuberant mesothelioma proliferation infiltrating and admixed with adipose tissue.

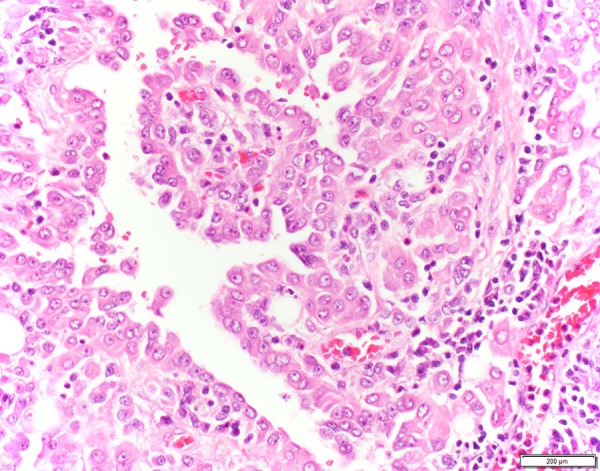

Figure 7.

High-power view of the biopsy reveals epithelioid morphology and nuclear atypia.

Discussion

Mesothelioma is a malignant neoplasm that originates from the mesothelial cells that line the serosal surfaces. While malignant mesothelioma of the pleura is the most common manifestation, mesothelioma can also occur in the peritoneal cavity. The incidence rates range between 0.5 and 3 cases per million in men and between 0.2 and 2 cases per million in women in industrialized nations [2]. It has been previously determined that cumulative asbestos exposure leads to a proportional increase in mesothelioma risk [3]. Mesothelioma can result from non-industrial environmental contact with asbestos fibers, and para-occupational exposure occurs; for example, women who have laundered their husband’s work-related clothing [4,5]. However there are several non-asbestos etiologies that are carcinogenic, such as therapeutic irradiation, chronic inflammatory peritonitis, and simian virus-40 [1,3]. In particular, this report describes a 76-year-old woman who had a history of gynecological malignancy who received subsequent therapeutic chemoradiation and had extensive non-industrial exposure to asbestos.

There are several different histological types of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: epithelioid, sarcomatous/fibrous, and biphasic [6]. Epithelioid type is the most common presentation, followed by biphasic and sarcomatoid types. Histologically, the epithelioid type demonstrates cells arranged in tubulopapillary or trabecular formations and can be predominantly composed of acinar structures and can be morphologically identical to adenocarcinoma [1,7]. The differential diagnosis of epithelioid malignant mesothelioma include metastatic adenocarcinoma of the ovaries, breasts, and lungs [8]. The patient described in this report ultimately was diagnosed with epithelioid type. Samedi et al. demonstrates that, in the setting of recurrent ascites requiring therapeutic paracentesis, cytologic examination of the fluid often yields inconclusive results [9]. However, the presence of atypical cells may increase suspicion of a malignant process. While cytology of the ascitic fluid may be useful in identifying the type of malignancy, it seldom leads to a definitive diagnosis. Based on the current literature, the most sensitive and specific means of diagnosis is through tissue biopsy with direct immunohistological staining. Cytokeratin staining is used to confirm invasion and to distinguish malignant mesothelioma from sarcoma or melanoma [10]. Malignant mesothelioma is further differentiated from adenocarcinoma by the use of specific markers: calretinin, WT1, cytokeratin 5/6, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), mesothelin, and anti-mesothelial cell antibody [6,10]. In addition to the positive staining for the aforementioned markers, the absence of staining for antigens such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), thyroid transcription factor-1, tumor glycoproteins MOC-31, B72.3 and Ber-EP4, and epithelial glycoprotein BG8 is necessary for definitive diagnosis [10]. The tissue biopsy of our patient stained positive for calretinin, CK5/6, WT-1, and was negative for CEA; thus, confirming the diagnosis.

Computed tomography (CT) is essential in diagnosis, characterization, staging, and guiding biopsy for tissue diagnosis [11]. CT findings are further divided into sub-categories. The “wet” type demonstrates little to no evidence of solid tumor in the peritoneum [12]. Ascites is the main presenting pathophysiology, leading to early symptoms of abdominal distention with minimal abdominal pain [11,13]. Occasionally these small nodules lining the parietal peritoneal surface are evident, especially beneath the right hemidiaphragm, causing additional symptoms [12]. The “dry” type is also known as the “painful” type. CT findings include diffuse peritoneal masses invading the omentum, which cause severe abdominal pain [11,12]. This omental studding becomes a focal point for bowel obstruction. There is an additional “mixed type”, which contains elements of both the wet and dry type. The patient described in this article almost certainly experienced the mixed type presentation with diffuse ascites, significant abdominal pain, and solid masses localized to the omentum, leading to small bowel obstruction.

Diagnosis can be difficult and delayed due to the presence of non-specific symptoms. This becomes especially challenging when there are other manifestations of the disease such as small bowel obstruction, appendicitis, new-onset hernias, fevers, and ovarian masses [14]. Clinically, de Pangher Manzini et al. reported that the most common presenting symptoms are as-cites and abdominal pain [15], followed by weakness, weight loss, anorexia, abdominal mass, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting [15]. The formation of recurrent ascites often coincides with extensive peritoneal seeding from widespread tumor growth. However, in long-term cancer survivors, the development of ascites within areas previously irradiated should raise suspicion of malignant mesothelioma [16]. These chronic peritoneal inflammatory changes lead to the development of persistent ascitic fluid accumulation [9]. Our patient developed recurrent ascites secondary to the chronic inflammatory changes from previous chemoradiation and widespread carcinomatosis. According to Kuroda et al., mesothelioma that occurs in the mesentery always presents as a thickening of the peritoneal surface [17]. This localized mass contained within the mesentery causes luminal obstruction of the small bowel [17]. Additionally, paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with peritoneal mesotheliomas. Ectopic hormone secretion of antidiuretic hormone, growth hormone, and corticotropic hormone has also been described. There is also a strong correlation with thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, and increased production of fibrin degradation products, leading to venous thrombosis [18]. Peritoneal mesothelioma can penetrate through the diaphragm, leading to development of respiratory symptoms.

The prognosis of peritoneal mesothelioma continues to remain poor. The median survival of patients with malignant mesothelioma from time of diagnosis is 12 months [10]. This survival rate progressively worsens in the male patient population, patients with extensive disease, leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytosis, sarcomatoid histological findings, or poor performance status [10]. Small bowel obstruction generally occurs late in the disease course and is a result of disseminated tumor burden [19]. Paraneoplastic elements were apparent in the reported patient and, coupled with the bowel obstruction, resulted in a complicated disease course with minimal survivability. Death is generally the consequence of intestinal obstruction, formation of fistula, and failure to thrive. New therapeutic treatments aim to prolong survival. These strategies consist of a combined approach with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy [6,8]. The cytoreductive surgery aims to separate adhesions and to remove bulky tumor masses. Smaller tumor masses that remain are more susceptible to the effects of the chemotherapy drugs [8, 10]. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy provides a significantly higher concentration of drug at tumor sites while reducing systemic adverse effects. Finally, the heat aids by intensifying the cytotoxic effect of the various chemotherapy agents [8]. However, our patient refused treatment and elected for palliative care.

Conclusions

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma is a rare malignant neoplasm. Diagnosis and treatment are challenging. Cumulative asbestos exposure, either directly or para-occupational, remains the most common factor related to the development of mesothelioma. In the absence of asbestos exposure, investigation must look elsewhere for causes such as therapeutic irradiation, chronic peritonitis, or oncogenic viruses. While there are many symptoms associated with this neoplasm, none are specific to mesothelioma. Peritoneal mesothelioma should be considered in patients with recurrent ascites, abdominal pain, distention, and abdominal masses. However, there is a wide array of other nonspecific symptoms that may complicate diagnosis with the potential for bowel obstruction in late-stage disease. Although cytology of ascitic fluid may prove useful in narrowing the diagnosis, definitive diagnosis is made through tissue biopsy with immunohistological staining. While current treatment therapies have increased survival rates, prognosis continues to remain poor. Early diagnosis and institution of therapy remain paramount.

Acknowledgments

All authors meet criteria for authorship.

References:

- 1.Attanoos R, Gibbs A. Pathology of malignant mesothelioma. Histopathology. 1997;30:403–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5460776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boffetta P. Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:985–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Algin MC, Yaylak F, Bayhan Z, et al. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: clinicopathological characteristics of two cases. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:748469. doi: 10.1155/2014/748469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee BTSSoC: Statement on malignant mesothelioma in the United Kingdom. Thorax. 2001;56:250–65. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.4.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donovan EP, Donovan BL, McKinley MA, et al. Evaluation of take home (para-occupational) exposure to asbestos and disease: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42:703–31. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.709821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih CA, Ho SP, Tsay FW, et al. Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013;29:642–45. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asensio JA, Goldblatt P, Thomford NR. Primary malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1990;125:1477–81. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410230071012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirarabshahii P, Pillai K, Chua TC, et al. Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma – an update on treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:605–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samedi V, White S, Zimarowski MJ, et al. Metastatic peritoneal mesothelioma in the setting of recurrent ascites: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:675–81. doi: 10.1002/dc.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson BWS, Lake RA. Advances in Malignant Mesothelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Primary neoplasms of peritoneal and sub-peritoneal origin: CT findings 1. Radiographics. 2005;25:983–95. doi: 10.1148/rg.254045140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugarbaker PH, Acherman YI, Gonzalez-Moreno S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of peritoneal mesothelioma: The Washington Cancer Institute experience. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:51–61. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.30236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma H, Bell I, Schofield J, Bird G. Primary peritoneal mesothelioma: case series and literature review. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethna K, Sugarbaker PH. Localized visceral invasion of peritoneal mesothelioma causing intestinal obstruction: a new clinical presentation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;52:1087–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pangher Manzini V, Recchia L, Cafferata M, et al. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a multicenter study on 81 cases. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:348–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bani-Hani KE, Gharaibeh KA. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:17–25. doi: 10.1002/jso.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroda K, Ishizawa S, Kudo T, et al. Localized malignant mesenteric mesothelioma causing small bowel obstruction. Pathol Int. 2008;58:239–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krasuski P, Poniecka A, Gal E. The diagnostic challenge of peritoneal mesothelioma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;266:130–32. doi: 10.1007/s004040100189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griniatsos J, Sougioultzis S, Dimitriou N, et al. Diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma presenting as intestinal obstruction. South Med J. 2009;102:1061–64. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181b671ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]