Abstract

Hypersensitivity in the allergic setting refers to immune reactions, stimulated by soluble antigens that can be rapidly progressing and, in the case of anaphylaxis, are occasionally fatal. As the number of known exposures associated with anaphylaxis is limited, identification of novel causative agents is important in facilitating both education and other allergen-specific approaches that are crucial to long-term risk management. Within the last 10 years several seemingly separate observations were recognized to be related, all of which resulted from the development of antibodies to a carbohydrate moiety on proteins where exposure differed from airborne allergens but which were nevertheless capable of producing anaphylactic and hypersensitivity reactions. Our recent work has identified these responses as being due to a novel IgE antibody directed against a mammalian oligosaccharide epitope, galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal). This review will present the history and biology of alpha-gal and discuss our current approach to management of the mammalian meat allergy and delayed anaphylaxis.

Keywords: IgE, alpha-gal, food allergy, mammalian meat

Introduction

IgE antibodies to carbohydrate epitopes on allergens are thought to be less common than IgE antibodies to protein epitopes and also of much less clinical significance (see www.allergen.org) [1–3]. Thus, when anaphylactic reactions to the monoclonal antibody cetuximab were recognized as a major regional complication of this cancer treatment the initial investigation focused on finding IgE antibodies (Ab) to a protein epitope [4]. It was a surprise when it became clear that these reactions were causally related to pre-existing IgE antibodies specific for the glycosylation on the Fab portion of this molecule [4]. This discovery, published in 2008, has led our research in several directions, most significant for this review is that the IgE Ab to alpha-gal also bind a wide range of non-primate mammalian products including beef, pork and lamb. An understanding of the tissue distribution of alpha-gal led us to recognize and describe a delayed food allergy to mammalian meat, where patients have allergic reactions 2–6 hours after the consumption of a culprit food.

Of Oncology Origin: The Cetuximab Story Related to Alpha-gal

During clinical trials of the monoclonal antibody cetuximab, which is specific for the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and used for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer, it became clear that the antibody was causing hypersensitivity reactions. Interestingly, the reactions were occurring primarily in a group of southern US states. The reactions to cetuximab developed rapidly and symptoms often peaked within 20 minutes following or during the first infusion of the antibody and occasionally proved fatal [4,5]. Ultimately, it was demonstrated that the patients who had reactions to cetuximab also had IgE antibodies specific for this molecule before they started treatment [4]. The question remained as to what epitope the IgE antibody was recognizing on the cetuximab molecule.

Characterization of cetuximab glycosylation, as measured by peak area on TOF-MS spectra, revealed 21 distinct oligosaccharide structures, of which approximately 30% have one or more alpha-1,3 linked galactosyl residues [6]. Analysis of the IgE antibodies to cetuximab demonstrated that these antibodies were specific for the oligosaccharide residues on the heavy chain of the Fab portion of the monoclonal antibody (mAb). From the known glycosylation of the molecule at amino acids 88 and 299, alpha-gal was identified as a possible relevant epitope [6]. Re-expression of cetuximab in a cell line unable to glycosylate with alpha-1,3-linked galactose residues failed to bind IgE, providing evidence that alpha-gal was in fact the target epitope [4]. Of the total alpha-gal in cetuximab, most of it is located in the Fab domain (Fab 990 nmol alpha-gal/μmol IgG versus Fc 140 nmol alpha-gal/μmol IgG) [6]. Recent mass spectrometry analysis indicated that glycosylation of cetuximab may be more complex than previously thought, containing both dianternary and trianternary structures [7]. Synthesis of alpha-gal requires the gene encoding alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase. In humans and higher primates this gene is not functional, so these species cannot produce alpha-gal – which in turn makes it possible for these animals to initially make IgG antibodies directed towards this oligosaccharide [8,9]. Of considerable importance to the development of biologics, in particular mAbs, is the observation that murine cell lines such as NS0 and Sp2/0 can place galactose in an alpha-1,3 linkage such that alpha-gal is present on the synthesized molecules. In fact, Sp2/0 was the cell line used to produce cetuximab. In those individuals who have IgE to alpha-gal, reactions are likely to occur directed against this mAb [10].

Connecting IgE to Alpha-gal to Red Meat

During a similar time period (2006–2008), we saw several patients in clinic who had presented with episodes of generalized urticaria, angioedema or recurrent anaphylaxis. Although there was no obvious immediate cause for the symptoms, in several cases the patients reported that they felt the reactions might be due to consumption of meat hours prior. Prick tests to commercially available meat extracts produced wheals only 2–4 mm in diameter that often would be interpreted as negative. However, given the compelling history described by the patients, we extended our analysis to intradermal skin testing with commercial meat extracts or prick skin tests with fresh meat extracts both of which demonstrated strong positive results [11]. These results were confirmed with blood tests for specific IgE Ab to red meats [11]. Three observations then led us to investigate whether IgE antibodies to alpha-gal were present in the sera of adult patients reporting reactions to beef. Alpha-gal is known to be present on both tissues and meat from non-primate mammals [12], the antibodies causing reactions to cetuximab were directed against alpha-gal, and the geographical distribution of the reactions to cetuximab overlapped the same geographical area where the red meat reactions were occurring. Not surprisingly, the patients’ sera tested positive for IgE to beef, pork, lamb, milk, cat and dog, but not to non-mammalian meat such as turkey, fish or chicken [11,13]. In studies with beef and pork food challenges, we have now documented that the appearance of clinical symptoms is delayed 3–5 hours after eating a typical serving of mammalian meat [14]. Moreover, during the same set of challenges, circulating basophils assessed ex vivo upregulated the expression of CD63 in a similar time frame as the patients developed symptoms [14].

Tick Bites and the Development of IgE Ab to Alpha-gal

Although an association between delayed reactions to mammalian meat and IgE Ab to alpha-gal was formalized in food challenges, this did not explain why adult patients who had fully tolerated beef for years suddenly experienced a break in tolerance and developed IgE Ab to alpha-gal. A relationship between mammalian meat allergy and tick bites had already been suggested in Australia [15], however the role of alpha-gal was not known and the tick connection was not initially obvious in the United States. An insight came when examining the geographical distribution of cetuximab reactions and delayed reactions to red meat: these syndrome were being reported from the same region of the country – a group of southeastern states. However, it was not clear why these cases were geographically localized and the only “disease” that appeared comparable was the maximum incidence of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF). In keeping with this connection, we started to ask patients about tick bites and rapidly became aware that most of those with delayed anaphylaxis had experienced recent bites from adult or larval ticks. Examination of CDC maps of the distribution of the tick Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick) revealed an overlap with the region of both cetuximab sensitivity and red meat allergy. Additional indications that tick bites are involved in the development of specific IgE to alpha-gal include: histories of bites that have itched for two or more weeks, a significant correlation between IgE Ab to alpha-gal and IgE to Lone Star tick as well as the prospective data on the increase in IgE to alpha-gal following known Lone Star tick bites [16]. Allergy to red meat is now being reported in other countries, but the ticks giving rise to this response are not the same species as in the United States. In Europe, Ixodes ricinus has been implicated while in Australia the relevant tick is Ixodes holocyclus [17–19]. In fact, there are now reports of delayed anaphylaxis to red meat in Australia [15,20], France [21,22], Germany [23,24], Sweden [25], Spain [26•], Japan [27], Korea [28] and Belgium [29]. Notably, in each of these countries there is evidence that tick bites are the primary cause of the sensitization [19••] and that the primary or sole sensitization is to alpha-gal.

Managing the Clinical Aspects of an Alpha-gal Allergy

The characteristics of red meat allergy are different from typical allergic reactions. Common complaints include both gastrointestinal symptoms and urticaria but unlike most allergic reactions, patients do not develop any symptoms for at least 2 hours after eating red meat. In point of fact, most reactions are delayed for 3–5 hours – some even longer. Recent work from Dr. Biedermann’s group has demonstrated two interesting points related to the timing of reactions in patients with IgE to alpha-gal [24••]. First, exercise (and/or other cofactors) can speed up the time to reaction such that a prolonged delay does not occur. Second, the tissue source of the meat – in this case pork kidney was used – can also alter the time to react by likely providing more or less antigen [24••]. Despite these variations in timing, symptoms can be severe or even life threatening. Many of the patients described nausea, diarrhea or indigestion before a reaction; however the most common symptom reported was itching (particularly palmar itching) [14]. The presence of symptoms before a severe reaction is common, but not a requirement. Many patients do not have any symptoms and even among those who have had a reaction previously, the symptoms did not occur with every exposure to red meat. All of the patients had consumed red meat without complications for many years prior to the onset of the syndrome. While some individuals had a prior history of allergy, most of the cases had no previous allergic symptoms, thus an atopic disposition does not appear to predispose patients to this kind of IgE response [30].

Diagnostically, skin testing for IgE to alpha-gal using beef, pork, or lamb extracts in both adult and pediatric patients has been challenging. Many patients have only small reactions (2–4mm) to these allergens by skin prick testing, and intradermal tests have been used in adults to clarify the intermediate results [11]. Overall, we are more likely to use the in vitro assays and typically re-assess IgE to alpha-gal levels every 8–12 months. Certainly one reason to monitor blood levels is that, based on our experience, if patients are able to avoid subsequent tick bites, the level of alpha-gal specific IgE tends to decrease over time. In fact, some adult and pediatric patients with this form of allergy have been able to tolerate mammalian meat again after avoiding additional tick bites for 1–2 years (Commins & Platts-Mills unpublished data). Unfortunately, the resolution of IgE Ab to alpha-gal does not appear to occur in every patient despite fastidious tick avoidance (Hoyt & Commins, manuscript in prep). At this time, we typically do not restrict dairy consumption for patients who can tolerate this form of the antigen. Alternatively, if patients report lingering symptoms such as non-specific abdominal pain or report frank reactions after dairy (especially premium ice creams) then we recommend expanding the avoidance diet to include dairy. In many instances, a single slice of cheese or cow’s milk in coffee can still be tolerated and individual dietary adjustments are suggested. An important note on an “appropriate” avoidance diet is that foods a patient may tolerate can fluctuate over time: either through prolonged tick bite avoidance and a waning IgE response or through recent tick bites and a heightened sensitivity.

Additional Clinical Implications of IgE Ab to Alpha-gal

Children

The early reports of alpha-gal sensitivity were mostly from adults with very few reports of affected children. However, children often have urticaria, angioedema or recurrent anaphylaxis for which the cause is unknown. We identified 51 children ages 4–17 with symptoms consistent with possible delayed allergic reactions to mammalian foods and measured IgE to alpha-gal in their sera. Serum IgE to alpha-gal was high in 45 of the subjects and there was a strong correlation with beef IgE as previously observed in the adults [13]. When questioned, these children gave a history of symptoms 3–6 hours after ingestion of meat and many could recall recent tick bites. The geographic distribution of affected children matches that of adults, namely the southeastern United States. Of note, we have identified several children with red meat allergy in referral from pediatric GI where they initially presented with non-specific abdominal pain and laboratory evaluation showed a positive IgE Ab to alpha-gal. Removal of red meat and, in one case, dairy led to resolution of symptoms. Thus, there may be an affected population of patients with non-specific abdominal symptoms who are not currently being identified as allergic to non-primate mammalian meat.

Vaccines

Hypersensitivity reactions to vaccines related to gelatin content as well as mammalian antigens has been discussed [20]. Subsequent to the report by Dr. Mullins, several patients with documented reactions to vaccines, especially Zostavax, have been identified by our group as well as by other physicians (manuscript in preparation). Zostavax contains over 15 mg of hydrolyzed porcine gelatin and many other vaccines may contain ingredients from growth media that could affect patients with IgE to alpha-gal (for instance, Mueller Hinton agar, which is used as a growth medium, has 30% beef infusion). Whether reactions to vaccines in patients with IgE to alpha-gal reflect a sensitivity to gelatin, specific ingredients of mammalian origin or other excipients with cross-reactivity remains to be elucidated.

Bio-prosthetics

A case report of three patients with IgE Ab to alpha-gal who had bovine or porcine valve replacement complicated by an allergic reaction in the immediate post-operative period was recently published [31•]. While the number of patients with delayed reactions to mammalian meat who require heart valve replacement is likely a quite small number, this issue is one that allergists should be aware of in order to provide patients with appropriate guidance. In the case report, the patients who had experienced the most severe reactions to red meat had the more significant clinical reactions post-operatively. It will be interesting to follow these patients to assess whether having IgE Ab to alpha-gal leads to premature valve failure as a recent report has formally demonstrated that alpha-gal moieties remain on the valves at time of implantation [32••].

Late Night Anaphylaxis

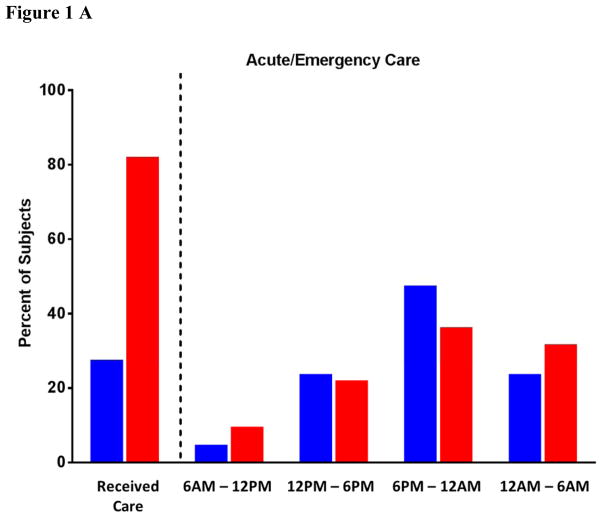

One of the more striking hallmarks that an undiagnosed patient’s history of urticaria, angioedema or anaphylaxis could be consistent with allergic reactions to red meat due to IgE to alpha-gal is the report of symptoms occurring after 6pm. In an analysis of >300 subjects with IgE to alpha-gal, of the 27% of patients with hives who received acute or emergency care over 60% of them presented after 6pm (21% after midnight). Equally, of the 76% of subjects who sought urgent care for anaphylaxis nearly 75% did so after 6pm (Fig 1A, blue bars). Unlike traditional protein-based food allergy that begins in childhood, the alpha-gal allergy is more prominent in adults (Fig 1B) – a nuance that has implications for physicians who see adult patients but may not be used to considering a diagnosis of food allergy.

Figure 1.

Percent of subjects (n=311) identified with delayed reactions to red meat and positive IgE Ab to alpha-gal with urticaria or angioedema (red bars) or anaphylaxis (blue bars) analyzed for time of presentation (A) and age of onset of first reaction attributable to mammalian meat allergy (B).

Conclusion

The finding that IgE to alpha-gal explains two novel forms of anaphylaxis has changed several established rules about allergic disease. Like so many new findings, this area of research provides both challenges and opportunities. We now have a model for understanding the ways in which ticks, parasites and perhaps stinging insects induce IgE responses without creating a risk for inhalant allergic disease. Bites from the Lone Star tick can cause high titer IgE Ab to alpha-gal and also major increases in total IgE. Further, these responses often occur in adults over 60 years of age and who have no prior allergic history. The specific factors that govern the IgE response to alpha-gal are currently unknown. Future efforts are being directed at understanding the role of T and B cells in this response as well as the mechanisms of isotype switch. We are also focused on exploring the delay in symptoms and identifying the relevant form of the antigen in circulation.

Acknowledgments

These studies are primarily funded by NIH grants: K08-AI-1085190.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- Fab

fragment antigen binding

- Fc

fragment crystallizable

- alpha-gal

galactose-α-1,3-galactose

- RMSF

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

References Cited

- 1.Aalberse RC, van Ree R. Crossreactive carbohydrate determinants. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1997;15:375–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02737733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Veen MJ, van Ree R, Aalberse RC, Akkerdaas J, Koppelman SJ, Jansen HM, van der Zee JS. Poor biologic activity of cross-reactive IgE directed to carbohydrate determinants of glycoproteins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Ree R, Aalberse RC. Specific IgE without clinical allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, Le QT, Berlin J, Morse M, Murphy BA, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mauro D, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neil BH, Allen R, Spigel DR, Stinchcombe TE, Moore DT, Berlin JD, Goldberg RM. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3644–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian J, Liu T, Yang L, Daus A, Crowley R, Zhou Q. Structural characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides on monoclonal antibody cetuximab by the combination of orthogonal matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization hybrid quadrupole-quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry and sequential enzymatic digestion. Anal Biochem. 2007;364:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayoub D, Jabs W, Resemann A, Evers W, Evans C, Main L, Baessmann C, Wagner-Rousset E, Suckau D, Beck A. Correct primary structure assessment and extensive glyco-profiling of cetuximab by a combination of intact, middle-up, middle-down and bottom-up ESI and MALDI mass spectrometry techniques. MAbs. 2013;5:699–710. doi: 10.4161/mabs.25423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koike C, Uddin M, Wildman DE, Gray EA, Trucco M, Starzl TE, Goodman M. Functionally important glycosyltransferase gain and loss during catarrhine primate emergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:559–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610012104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galili U. The alpha-gal epitope and the anti-Gal antibody in xenotransplantation and in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:674–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maier S, Chung CH, Morse M, Platts-Mills T, Townes L, Mukhopadhyay P, Bhagavatheeswaran P, Racenberg J, Trifan OC. A retrospective analysis of cross-reacting cetuximab IgE antibody and its association with severe infusion reactions. Cancer Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cam4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commins SP, Satinover SM, Hosen J, Mozena J, Borish L, Lewis BD, Woodfolk JA, Platts-Mills TA. Delayed anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria after consumption of red meat in patients with IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thall A, Galili U. Distribution of Gal alpha 1----3Gal beta 1----4GlcNAc residues on secreted mammalian glycoproteins (thyroglobulin, fibrinogen, and immunoglobulin G) as measured by a sensitive solid-phase radioimmunoassay. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3959–3965. doi: 10.1021/bi00468a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy J, Stallings A, Platts-Mills T, Oliveira W, Workman L, James H, Tripathi A, Lane C, Matos L, Heymann P, et al. Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose and Delayed Anaphylaxis, Angioedema, and Urticaria in Children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commins SP, James HR, Stevens W, Pochan SL, Land MH, King C, Mozzicato S, Platts-Mills TA. Delayed clinical and ex vivo response to mammalian meat in patients with IgE to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Nunen SA, O’Connor KS, Clarke LR, Boyle RX, Fernando SL. An association between tick bite reactions and red meat allergy in humans. Med J Aust. 2009;190:510–511. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commins SP, James HR, Kelly LA, Pochan SL, Workman LJ, Perzanowski MS, Kocan KM, Fahy JV, Nganga LW, Ronmark E, et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1286–1293. e1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AF, Hamilton DL. Tick bite anaphylaxis in Australia. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15:111–113. doi: 10.1136/emj.15.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauci M, Loh RK, Stone BF, Thong YH. Allergic reactions to the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus: diagnostic evaluation by skin test and radioimmunoassay. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1989.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamsten C, Starkhammar M, Tran TA, Johansson M, Bengtsson U, Ahlén G, Sällberg M, Grönlund H, van Hage M. Identification of galactose-α-1,3-galactose in the gastrointestinal tract of the tick Ixodes ricinus; possible relationship with red meat allergy. Allergy. 2013 doi: 10.1111/all.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullins RJ, James H, Platts-Mills TA, Commins S. Relationship between red meat allergy and sensitization to gelatin and galactose-α-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1334–1342. e1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisset M, Richard C, Astier C, Jacquenet S, Croizier A, Beaudouin E, Cordebar V, Morel-Codreanu F, Petit N, Moneret-Vautrin DA, et al. Anaphylaxis to pork kidney is related to IgE antibodies specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. Allergy. 2012;67:699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacquenet S, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Bihain BE. Mammalian meat-induced anaphylaxis: clinical relevance of anti-galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose IgE confirmed by means of skin tests to cetuximab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jappe U. Update on meat allergy : α-Gal: a new epitope, a new entity? Hautarzt. 2012;63:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s00105-011-2266-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer J, Hebsaker J, Caponetto P, Platts-Mills TA, Biedermann T. Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose sensitization is a prerequisite for pork-kidney allergy and cofactor-related mammalian meat anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:755–759. e751. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamsten C, Tran TA, Starkhammar M, Brauner A, Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA, van Hage M. Red meat allergy in Sweden: Association with tick sensitization and B-negative blood groups. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Quintela A, Dam Laursen AS, Vidal C, Skaaby T, Gude F, Linneberg A. IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in the general adult population: relationship with tick bites, atopy, and cat ownership. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:1061–1068. doi: 10.1111/cea.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekiya K, Fukutomi Y, Nakazawa T, Taniguchi M, Akiyama K. Delayed anaphylactic reaction to mammalian meat. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:446–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JH, Kim JH, Kim TH, Kim SC. Delayed mammalian meat-induced anaphylaxis confirmed by skin test to cetuximab. J Dermatol. 2013;40:577–578. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebo DG, Faber M, Sabato V, Leysen J, Gadisseur A, Bridts CH, De Clerck LS. Sensitization to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal): experience in a Flemish case series. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:206–209. doi: 10.2143/ACB.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commins SP, Kelly LA, Rönmark E, James HR, Pochan SL, Peters EJ, Lundbäck B, Nganga LW, Cooper PJ, Hoskins JM, et al. Galactose-α-1,3-galactose-specific IgE is associated with anaphylaxis but not asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:723–730. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2017OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mozzicato SM, Tripathi A, Posthumus JB, Platts-Mills TA, Commins SP. Porcine or bovine valve replacement in 3 patients with IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:637–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naso F, Gandaglia A, Bottio T, Tarzia V, Nottle MB, d’Apice AJ, Cowan PJ, Cozzi E, Galli C, Lagutina I, et al. First quantification of alpha-Gal epitope in current glutaraldehyde-fixed heart valve bioprostheses. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:252–261. doi: 10.1111/xen.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]