Abstract

Semantic preview benefit in reading is an elusive and controversial effect because empirical studies do not always (but sometimes) find evidence for it. Its presence seems to depend on (at least) the language being read, visual properties of the text (e.g., initial letter capitalization), the type of relationship between preview and target, and as shown here, semantic constraint generated by the prior sentence context. Schotter (2013) reported semantic preview benefit for synonyms, but not semantic associates when the preview/target was embedded in a neutral sentence context. In Experiment 1, we embedded those same previews/targets into constrained sentence contexts and in Experiment 2 we replicated the effects reported by Schotter (2013; in neutral sentence contexts) and Experiment 1 (in constrained contexts) in a within-subjects design. In both experiments, we found an early (i.e., first-pass) apparent preview benefit for semantically associated previews in constrained contexts that went away in late measures (e.g., total time). These data suggest that sentence constraint (at least as manipulated in the current study) does not operate by making a single word form expected, but rather generates expectations about what kinds of words are likely to appear. Furthermore, these data are compatible with the assumption of the E-Z Reader model that early oculomotor decisions reflect “hedged bets” that a word will be identifiable and, when wrong, lead the system to identify the wrong word, triggering regressions.

Recently, researchers have debated whether, and to what extent, readers obtain semantic preview benefit from the upcoming word during reading (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2013; Hohenstein, Laubrock, & Kliegl, 2010; Rayner, 2009; Rayner & Schotter, 2014; Rayner, Schotter, & Drieghe, 2014; Schotter, 2013; Schotter, Angele, & Rayner, 2012; Yan, Richter, Shu, & Kliegl, 2009; Yang, Wang, Tong, & Rayner, 2010). Semantic preview benefit refers to the phenomenon in the boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975) in which reading times on a fixated target word are faster when a preview word previously in its location (i.e., before it was fixated) is semantically related to the target, compared to unrelated. Semantic preview benefit is controversial because its presence varies depending on which language is tested; originally, semantic preview benefit was not observed in English (Rayner, Balota, & Pollatsek, 1986; Rayner, Schotter, & Drieghe, 2014) but was observed in German (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014; Hohenstein, Laubrock, & Kliegl, 2010) and Chinese (Yan, Richter, Shu, & Kliegl, 2009; Yan, Zhou, Shu, & Kliegl, 2012; Yang, 2013; Yang, Wang, Tong, & Rayner, 2010). The inconsistency with which semantic preview benefit is observed raises the issue of, not whether it is real, but rather what conditions are necessary and sufficient for it to be observed, which will potentially lead us to a better understanding of the reading process as a whole.

Recently, Schotter (2013) did find evidence for semantic preview benefit in English, but only when the preview and target were synonyms (e.g., start begin), not if they only shared an associative semantic relationship (e.g., ready begin). Furthermore, Rayner and Schotter (2014) tested whether an orthographic property that differs between English and German (i.e., capitalization of the first letter of nouns) might partially explain these cross-language differences. They found that, in English, initial letter capitalization increased the magnitude of preview benefit generally, and led to semantic preview benefit (for similar effects in German, see Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014).

One of the reasons semantic preview benefit is controversial is because many researchers presume that firm evidence for its presence would either be incompatible with the E-Z Reader model (a serial attention shift model of oculomotor control in reading) or would only be possible under very specific and rare circumstances (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014). However, Schotter, Reichle, and Rayner (2014) used E-Z Reader to simulate the data from Schotter (2013) and demonstrated that semantic preview benefit is not incompatible with its architecture. The components of the model can be grouped into five broad categories: (1) pre-attentive visual processing, which occurs for multiple words so long as they are within the limits of the perceptual span; (2) two serial stages of lexical processing (L1 is an early, cursory stage and L2 is a late, full identification stage); (3) attention allocation; (4) post-lexical integration of word meanings; and (5) two stages of saccade programming (M1, which is labile (cancellable) followed by M2, which is non-labile). The completion of the first lexical processing stage (L1) initiates both the second stage (L2) and the beginning of saccade programming (M1). Thus, because saccade programming is triggered by the completion of only cursory lexical processing, these saccade decisions are considered “dumb” in that they are not initiated based on complete lexical identification of the word. The model accounts for preview benefit by means of the relative timing of the completion of lexical processing on the current word and the saccade away from it. For example, saccade programming requires about 125 ms from the start of planning until execution; if the completion of lexical identification (i.e., L2, which is initiated at the same time as saccade programming) occurs before this time, attention shifts to the upcoming word and begins cursory lexical processing (i.e., L1) on the upcoming word before the eyes move to it.

Schotter et al. took a new perspective on modeling the boundary paradigm, with the E-Z Reader model and thus a new consideration of how parafoveal processing influences the reading process. Specifically, they used the model to estimate how far into lexical processing of the parafoveal word the model had progressed. In the simulations of Schotter’s (2013) data, the model estimated that preprocessing of the preview had reached the L2 stage of the model (i.e., semantic processing) a modest but non-trivial 8% of the time. Importantly, although not discussed by Schotter et al., (2014), a corollary of this finding is that in these cases the model had also reached the stage of saccade programming away from the parafoveal word because the end of the L1 stage initiates both the start of L2 and the start of M1 (i.e., saccade programming). We will return to this idea in the General Discussion.

Given that the other languages that demonstrate semantic preview benefit did not exclusively use synonym previews, the type of semantic relationship cannot be the only explanation of cross-language differences. Schotter (2013; see also Laubrock & Hohenstein, 2012) suggested that these cross-language differences in the presence of semantic preview benefit might be explained by differences in orthography; languages with an orthography that is shallow (e.g., German) or non-alphabetic (e.g., Chinese) might be more likely to show the effect because semantics may be accessed sooner during preview, due to less time spent decoding phonology (compared to in English). As a consequence, the earlier access to semantic information from the preview in German and Chinese might allow more time for spreading activation among semantic representations in the linguistic system, allowing for something akin to semantic priming (Schotter, 2013). A direct test of this hypothesis is difficult because it is not possible to rigorously control all the differences across these languages while manipulating the theoretically relevant variables. Instead, in the present study we turn to a different contributing factor to the reading process (and semantic pre-activation) that has received little attention in relation to semantic preview benefit thus far, but may be an important consideration: contextual constraint or expectations of upcoming words (see below).

The influence of sentence context on reading

While it is well-demonstrated that the meaning generated from the prior sentence context exerts an influence on language processing, the exact nature of this effect is poorly understood. Part of the lack of clarity surrounding the effect of sentence context is that, across studies, researchers have manipulated it in different ways, measured it with different methods, and used different theoretical constructs to discuss it.

DeLong, Troyer, and Kutas (2014) provide an overview of the distinction between different theoretical constructs, highlighting the following terms, which we will group further as they pertain to reading. 1. Prediction suggests an active, conscious, effortful process in which a single item is predicted and there are benefits for success (i.e., if the predicted word is encountered) and costs for failure (i.e., if any other word is encountered). This construct is more likely to operate in more strategic tasks that require an overt judgment, for which the response time is slower than the typical eye movement in reading (e.g., 250 ms). 2. Pre-activation/Anticipation suggests a less specific process, for which ‘landscapes’ of pre-activated items (i.e., multiple possible words) are dynamically shifted by all available information sources. This construct is a more apt description of what may be happening during reading in that parafoveal (and subsequently foveal) visual information may be what reshapes the “landscapes” of pre-activated semantic concepts that were generated by the context. 3. Lastly, De Long et al. (2014) note that predictability “can be divorced from prediction, in that an item can be predictable even if it is not predicted” (p. 633), which leads us to the issue of how one can measure expectations generated by the sentence context and the degree to which such measures relate to processes involved in reading.

Word form cloze predictability

The most common way to determine the effect of the sentence context on word recognition in reading is to create sentences in which a particular word is highly expected in a particular location (e.g., “The children went outside to…”). To confirm the manipulation, researchers use a modified cloze task (see Taylor, 1953 for the original cloze task) in which the prior sentence context is provided (as above) and subjects supply the word that they think comes next. Typically, the way these data are analyzed is by coding the response as correct (e.g., 1) if the subject supplied the word that the experimenter intended (e.g., “play” in the example, above) and incorrect (e.g., 0) if the subject supplies any other word; the predictability of a word is determined as the proportion of “1” responses for that word. There are some modifications to this coding scheme (e.g., accepting the intended word’s plural/singular counterpart or other small morphological variations), but for the most part this procedure is used to determine how expected a particular word form is, given the context. In order to create a comparison of predictability, reading times on these highly expected words are contrasted with reading times on a word that was never or rarely supplied by the subjects in the norming procedure, but is nonetheless a plausible word that makes sense in the exact same sentence (e.g., “swim” in the example above; generally, this is confirmed with another norming task in which subjects rate how acceptable/sensible the sentence is).

Using this manipulation, several reading studies have found that both the likelihood of fixating a word and the duration of the fixation are modulated by cloze predictability (Balota, Pollatsek, & Rayner, 1985; Drieghe, Rayner, & Pollatsek, 2005; Ehrlich & Rayner, 1981; Kliegl, Grabner, Rolfs, & Engbert, 2004; Rayner, Slattery, Drieghe, & Liversedge, 2011; Rayner & Well, 1996; Zola, 1984). Initially, researchers hypothesized that the effect of predictability was the manifestation of the reading system “guessing” the upcoming word (e.g., McClelland & Oregan, 1981a,b; cf. Rayner & Slowiaczek, 1981), similar to the “prediction” account described by De Long et al. (2014). On this view, the system uses parafoveal preview to confirm this guess (i.e., that there is a linear relationship between predictability and reading time; see Smith & Levy, 2013 for a discussion). This is the underlying assumption in both the E-Z Reader (Reichle, Pollatsek, Fisher, & Rayner, 1998) and SWIFT (Engbert, Nuthmann, Richter, & Kliegl, 2005) models of oculomotor control in reading.

Recently, however, there have been several findings that question the interpretation that individual words are guessed or predicted. First, the relationship between cloze predictability and reading time is not linear, but rather varies across the predictability spectrum: in reading studies, words that have a high or moderate cloze predictability are fixated for less time than words that have a low cloze predictability, but there does not seem to be much distinction between words with high or moderate cloze predictability (Rayner & Well, 1996; see also, Ehrlich & Rayner, 1981; Hyönä, 1993). This inconsistency could be due to limitations of the cloze task in measuring small differences in absolute predictability, or due to a logarithmic relationship between predictability and reading time. Indeed, a logarithmic relationship was reported by Smith and Levy (2013), who concluded that this relationship suggests “the comprehension system must be able to simultaneously pre-activate large portions of its lexicon in a quantitatively graded fashion” (p. 311). Perhaps then, despite the fact that cloze predictability demonstrates a very strong quantitative relationship with reading times, measuring the effect of context on word processing in this way may not fully capture how readers use context to make reading more efficient. Therefore, we must consider other ways in which the effect of context can be measured.

Contextual constraint

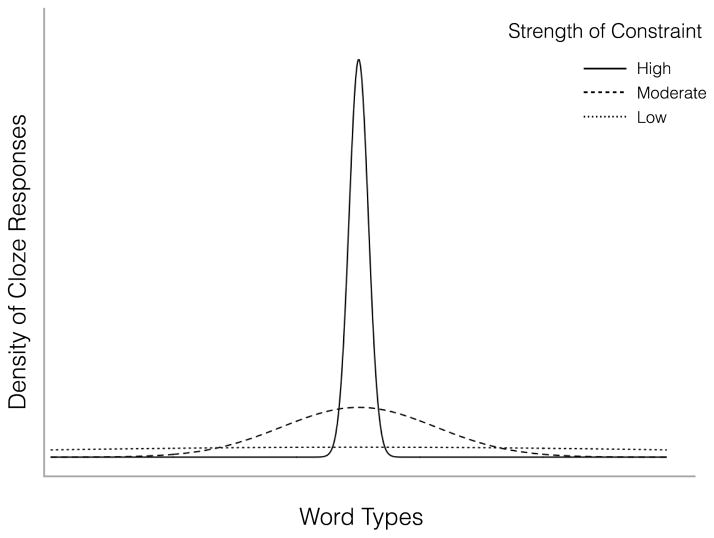

As an alternative to cloze predictability, which focuses primarily on differing degrees of expectations for different words given the same context, some researchers have employed manipulations of the context itself. One of the limitations of using the cloze task to measure these manipulations is that the primary way it is coded and used to generate stimuli for experiments obscures information about the distribution of responses, which may be of theoretical importance when considering the reading process. For example, a moderately constraining sentence generally leads to cloze probabilities of around .3 to .6, meaning that a particular word form is supplied by one third to two thirds of the subjects tested. But given that very same outcome, there could be many different underlying distributions. Figure 1 demonstrates the cleanest mathematical relationship one could imagine (i.e., constraint works by decreasing the standard deviation of the distribution of responses, honing on words surrounding a particular meaning or event). It is most straightforward to compare a very high constraint sentence in which one word form is highly favored (e.g., a cloze probability of .8 or higher) and almost no other word forms are provided (e.g., cloze scores of < .1) with a low constraint sentence in which there is almost no consistency in the responses, with all word forms having low cloze scores. The interpretation of such a comparison would lend support to the “prediction” hypothesis, described above, because the constraint serves to change the expectations for a single word. However, it is not clear that extremely high cloze sentences are that common, given that they are relatively uninformative (i.e., do not add any new information since the comprehender can infer the completion). One could argue that very high constraint sentences (e.g., “The opposite of black is...”) constitute a qualitatively different type of sentence, rather than an extreme on the constraint continuum (however, adjudicating between these possibilities is beyond the scope of this paper). Thus, it may be more informative to consider sentences with a moderate degree of constraint. That is, such sentences raise the expectations for a particular word form with some consistency, but do not make that word obligatory.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical density distributions of words provided in the cloze task as a function of sentence constraint.

More important for the present study, however, is the question of what the nature of the other responses in moderate cloze sentences looks like. For example, if provided with the sentence, “At the dog show, Spot had the most points and won the coveted…” the experimenter’s intended target word could be “prize,” and in our norming task (see below) this word form was provided 40% of the time aligning with the conclusion that the sentence provides a moderate degree of cloze. However, inspection of the other responses suggests that crucial information is missing from this coding scheme: “award”, “medal”, and “ribbon” were provided 20%, 10% and 10% of the time, respectively. If one assumes that theses are acceptable synonyms of the target, then we might conclude that the constraint of the sentence is actually quite high (i.e., including all of these responses because the meaning was predicted leads to a cloze score of 80%). Additionally, one could argue that the remaining responses “bone” and “blue” satisfy this coding principle, as well, assuming that a bone would be a nice prize for a dog and that blue was provided because the subject imagined a “blue ribbon” as the prize. Thus, this sentence actually generates a high degree of expectation surrounding the writer’s intended idea (i.e., a reward for a good job), but that this idea can manifest itself as a variety different word forms.

An interesting potential consequence of sentence constraint acting in this way is that we would expect, in contrast to the “prediction” hypothesis, that increasing constraint to a moderate level (i.e., not to the point where one word is obligatory) would make it easier to read, not only the highest cloze word, but also words that are related to the meaning that the reader expects. Indeed, this is what Kutas and Hillyard (1984) found when they measured event related brain potentials (ERPs) to the final words in sentences that were constrained to varying degrees. In this study, Kutas and Hillyard manipulated both the sentence constraint and the target word orthogonally, allowing them to investigate the effect of both variables. However, they note that, because these variables are intrinsically tied, it is impossible to fully dissociate them; cloze probabilities of the best completion in the high constraint sentences were much higher (.92) than in the moderate (.63) and low constraint sentences (.29). When they compared the ERPs across conditions, they found that the most expected word in the most constrained context did not elicit a significant N400 (considered an index of the difficulty of semantic processing; DeLong et al., 2014), but low-cloze words in all sentence constraint conditions elicited N400s of approximately similar amplitudes. In contrast, when comparing ERPs to the best completions across degrees of sentence constraint they found graded effects related to the amplitude of the N400 component, which lends support for the idea of landscapes of pre-activation.

Additionally, Kutas & Hillyard (1984) found the largest N400 to words that were unrelated to the best completion (e.g., “Don’t touch the wet dog” when the word with the highest cloze was “paint”) and a relatively reduced N400 for words that were semantically related to the best completion (e.g., “coffee” in the sentence “He liked lemon and sugar in his____” where the best completion was “tea”), even though both words had extremely low cloze probabilities and were perfectly acceptable completions. From these data it is unclear whether the reduction in the N400 to these semantically related words stems from distributed pre-activation (i.e., that “coffee” was, to some degree, pre-activated) or to semantic spreading activation from the most highly provided response. However, one could argue that these two interpretations are part and parcel of the same process of distributed expectations.

Further evidence that multiple meanings are being pre-activated comes from a study investigating (self-paced) reading times; Roland, Yun, Koenig, and Mauner (2012) created moderately constraining contexts (e.g., “The aboriginal man jabbed the angry lion with a/an ____”) that yielded a distribution of responses in the modified cloze task, generally surrounding a particular semantic feature (e.g., pointed objects). They compared reading times on words in these sentences with words in sentences that were less semantically constraining (e.g., replacing the word “jabbed” with “attacked” creates less of a preference for a pointed instrument completion). Roland et al. (2012) found that the degree of semantic similarity (measured via latent semantic analyses LSA) between the most expected word (Mcloze(p) = .24) and the word provided (in the reading task) significantly predicted processing time; reading times were shorter when the provided word was semantically similar to the expected word than when it was semantically dissimilar, even though both words were in the low-cloze probability range (Mcloze(p) = .02).

Prediction beyond single words: predicting events

There is one further issue when considering the use of cloze probability to measure the effect of the sentence context, which relates to the distinction between predictability and prediction. Mainly, when subjects provide responses in the cloze task, they (almost always) provide a single word that satisfies the semantic and syntactic constraints imposed on that sentence position (cf. Roland et al., 2012). That is, the sentence “The children went outside to…” must be completed with a verb to be grammatical. However, in the scenario that the subject imagines in order to complete this task, she may imagine not only the action she will provide, but also auxiliary event-related information. For example, if the subject completing the cloze task were in a northern location in winter, she might imaging that “play” in this scenario entails building a snowman, having a snowball fight, sledding, etc. Therefore, even though almost all the subjects would respond with “play” (perhaps because of its high lexical frequency, or because the idea is fairly cliché) does not mean that they are not also imagining these other entities that are not grammatically licensed, which may be part of elaborative inference or other discourse comprehension processes.

There is empirical data to support this suggestion. Metusalem, Kutas, Urbach, Hare, McRae, and Elman (2012) conducted an ERP experiment in which subjects read short, two-sentence scenarios that set up a particular event (e.g., “A huge blizzard ripped through town last night. My kids ended up getting the day off from school.”) They then read a third sentence with one of three possible target words (e.g., They spent the whole day outside building a big ______ in the front yard.”) and compared the ERP waveforms across those words. The three words were (1) a highly expected word (snowman; Mclozep = .81), (2) a contextually anomalous word that was related to the event (jacket; Mclozep = .00), or (3) a contextually anomalous word that was unrelated to the event (towel; Mclozep = .00). Metusalem et al. (2012) found a reduced N400 for the event-related word compared to the event-unrelated word, even though neither word was ever produced in the cloze norming task. Thus, these data support the idea that sentence (or in this case, discourse) contexts can generate expectations for event-related words beyond just the next, grammatically- and semantically-licensed word.

The interaction between context and parafoveal preview

Taken together, these findings (Kutas & Hillyard, 1984; Metusalem et al., 2012; Roland et al., 2012) suggest that the sentence context pre-activates (and consequently facilitates processing of) a non-singular set of ideas and words. Given that both contextual constraint and parafoveal preview exert robust effects on reading behavior, the question remains how their influences interact to affect online processing. Crucially, the use of the boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975) allows us to dissociate the information the reader has about the preview word (in parafoveal vision) from the target word (once it is fixated). An advantage of this experimental design is that it allows us to provide the reading system with previews of words that may not make sense grammatically in the sentence, which change to sensible target words once the display change occurs. Therefore, any potential disruption to comprehension that is created by the hedged bet based on a preview of a semantically associated but grammatically inappropriate word can be repaired if the reader makes a regression to view the perfectly sensible target word. It is likely, then, that the identity of the preview would have more of an influence on early reading measures (e.g., single fixation duration and gaze duration) than on later reading measures (e.g., total reading time) when the system has had more time to encounter the target.

The present study uses the boundary paradigm and the preview manipulation employed by Schotter (2013; identical, synonym, semantically associated, and unrelated) and introduces a manipulation of contextual constraint. That is, Schotter exclusively used neutral sentences with very low cloze probabilities for any of the preview or target words in order to investigate the influence of parafoveal preview alone. But a crucial part of much of the theorizing about the reading process (described above) suggests that contextual constraint may change how preview benefit effects are manifested (i.e., by changing expectations about what words should or could appear). Therefore, it is important to empirically test whether and how expectations about and parafoveal preview of words change the way they are read.

Experiment 1

Method

Subjects

Forty undergraduates at the University of California San Diego participated in the experiment for course credit. All subjects were native English speakers with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve to the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus

Eye movements were recorded with an SR Research Ltd. Eyelink 1000 eye tracker (with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz) in a tower setup that restrains head movements with forehead and chin rests. Viewing was binocular, but only the movements of the right eye were recorded. Subjects were seated approximately 60 cm away from a 20” HP p1230 CRT monitor with a screen resolution of 1024 x 768 pixels and a refresh rate of 150 Hz. The sentences were presented in the center of the screen with black Courier New 14-point font on a white background and were always presented in one line of text with 3.8 characters subtending 1 degree of visual angle. Following calibration, eye position errors were (maximally) less than 0.3°. The display change was completed, on average, within 4 ms (range = 0–7 ms) of the tracker detecting a saccade crossing the boundary.

Materials and Design

Stimuli were created using the targets and previews from Schotter (2013; Table 1): identical (begin begin), synonym (start begin), semantically related (ready begin) and unrelated (check begin). The semantically related condition consists of semantic associates of the target word. In contrast to Schotter (2013), each target item was presented in a biased sentence context that constrained toward the meaning of the target/synonym (see Appendix and normative data section, below). The target word was always preceded and followed by a minimum of three words.

Table 1.

Lexical characteristics of and normative data for target and preview words used in the experiments. Standard errors are in parentheses.

| Variable | Target Identical | Preview Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synonym | Semantic | Unrelated | ||

| Length | 5.61 (1.46) | 5.61 (1.46) | 5.61 (1.46) | 5.61 (1.46) |

| Log Frequency (HAL) | 8.31 (1.86) | 10.26 (1.46) | 8.99 (2.11) | 10.04 (1.53) |

| Total Letters Shared with Target | -- | .72 (.09) | .81 (.10) | .55 (.07) |

| Initial Letters Shared with Target | -- | .09 (.03) | .15 (.05) | .09 (.03) |

| Cloze p in Neutral Contexts | .02 (.05) | .05 (.12) | .00 (.02) | .00 (.01) |

| Cloze p in Constrained Contexts | .21 (.02) | .25 (.03) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| Preview-Target Relatedness (1–9 scale) | -- | 7.5 (.97) | 5.6 (1.5) | 2.4 (.97) |

Normative Data

Fifteen UCSD students, who did not participate in the reading experiment, participated in a cloze norming task to evaluate the predictability of the target and preview words. This norming task revealed that the sentences were moderately constraining toward the meaning of the target/synonym, with (on average) the target only being produced on average 21% of the time, the synonym being produced 25% of the time, the semantically related and unrelated words being produced 0% of the time. However, as discussed in the Introduction, this traditional way of coding cloze data does not capture the extent to which the sentence constrains to the meaning that is shared by the target and synonym (e.g., when both the target and synonym are accepted the joint cloze probability is 46%). Therefore, to create a measure that more readily captures subjects’ expectations we also coded the responses for whether any word representing that general idea was reported (see Introduction) and found cloze probabilities of, on average, 75%. These responses were coded independently by two of the experimenters and the inter-rater reliability was quite high (Pearson’s r = .9).

Procedure

Subjects were instructed to read the sentences for comprehension and to respond to occasional comprehension questions, pressing the left or right trigger on the response controller to answer yes or no, respectively. At the start of the experiment (and during the experiment if calibration error was greater than .3 degrees of visual angle), the eye-tracker was calibrated with a 3-point calibration scheme. At the beginning of the experiment, subjects received five practice trials, each with a comprehension question, to allow them to become comfortable with the experimental procedure.

Each trial began with a fixation point in the center of the screen, which the subject was required to fixate until the experimenter started the trial. Then a fixation box appeared on the left side of the screen, located at the start of the sentence. Once a fixation was detected in this box, it disappeared and the sentence appeared. The sentence was presented on the screen until the subject pressed a button signaling they had completed reading the sentence. The target replaced the preview once the subject’s gaze crossed an invisible boundary located before the space before the target and took between 0 and 7 ms to complete. Subjects were instructed to look at a target sticker on the right side of the monitor beside the screen when they finished reading to prevent them from looking back to a word (in particular, the target, which was often located in the center of the sentence, near the location of the fixation point that started the next trial) as they pressed the button. Comprehension questions followed 30 (41%) of the sentences, requiring a “yes” or “no” response. Comprehension accuracy was very high (on average 93%). The experimental session lasted approximately thirty minutes.

Results and Discussion

The same data processing procedure used in Schotter (2013) was used in this experiment: Fixations shorter than 80 ms within one character of a previous or subsequent fixation were combined. All remaining fixations shorter than 80 ms or longer than 800 ms were eliminated. Trials in which there was a blink or track loss on the target word or on an immediately adjacent word during first pass reading were excluded, as were trials in which the display change was triggered by a saccade that landed to the left of the boundary or trials in which the display change was completed late. Additionally, gaze durations longer than 2,000 ms and total times longer than 4,000 ms were excluded, as well as any fixation duration measures that were more than 3 standard deviations from the mean for that measure for that subject. These data exclusions left 4920 trials (85% of the original data) available for analysis.

We report standard reading time measures (Rayner, 1998) used to investigate the time-course of word processing in reading. This includes measures of fixation time when the word was fixated, which can be divided into early measures (i.e., those that terminate at the end of first-pass reading: once the reader’s eyes move away from it for the first time) and late measures (i.e., those that include time spent re-reading the target word or words prior to it). Early reading time measures include first fixation duration (the duration of the first fixation on the word, regardless of how many fixations are made), single fixation duration (the duration of a fixation on a word when it is the only fixation on that word in first pass reading), and gaze duration (the sum of all fixations on a word prior to leaving it, in any direction). Late reading time measures include go-past time (the sum of all fixations on a word and any words to the left of it before going past it to the right), and total time (the sum of all fixations on a word, including time spent re-reading the word after a regression back to it). Because go-past time incorporates re-reading previous words after a regression out of the target and total time includes rereading the target after a regression from subsequent words, go-past time can be considered an earlier late measure than total time.

Data were analyzed using inferential statistics based on generalized linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) with preview entered as a fixed effect with planned contrasts (see below) and subjects and items as crossed random effects (see Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008), using the maximal random effects structure (Barr, Levy, Scheepers & Tily, 2013)2. There were three planned contrasts built into the model: one tested the difference between the identical condition and the unrelated condition (i.e., an identical preview benefit), another tested for a difference between the synonym and the unrelated condition (i.e., a synonym preview benefit), and the third tested for a difference between the semantically related condition and the unrelated condition (i.e., a semantically related preview benefit). Contrasts were achieved by setting the unrelated condition to the baseline (intercept) in the model and using dummy coded variables to test for the individual contrasts for the comparisons of each of the other conditions to the unrelated condition.

In order to fit the LMMs, we used the lmer function from newest lme4 package (version 1.1–7; Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2014) within the updated R Environment for Statistical Computing (R Development Core Team, 2014). For fixation duration measures, we report linear mixed-effects regressions on the raw data: regression coefficients (b), which estimate the effect size (in milliseconds) of the reported comparison, and the (absolute) t-value of the effect coefficient are reported. Log-transforming the dependent variable had almost no effect on the patterns of significance, so for transparency we report the results from the untransformed models. For binary dependent variables (fixation probability data), logistic mixed-effects regression models were used, and regression coefficients (b), which represent effect size in log-odds space, and the (absolute) z value and p value of the effect coefficient are reported. Absolute values of the t and z statistics greater than or equal to 1.96 indicate an effect that is significant at approximately the .05 alpha level.

Fixation duration measures

Because it is of theoretical interest to the oculomotor models of reading, we first analyzed whether the different previews had an effect on gaze duration on the pretarget word (i.e., whether we observed a parafoveal-on foveal effect; see Drieghe, 2011 for a review). If we were to find such an effect, it would suggest that readers had processed the upcoming word extensively, prior to making a saccade toward it. However, there were no differences across conditions for gaze duration on the pretarget word (247 ms, 248 ms, 249 ms, and 244 ms in the identical, synonym, semantically associated, and unrelated conditions, respectively; all ts < 1.26), indicating no parafoveal-on-foveal effects.

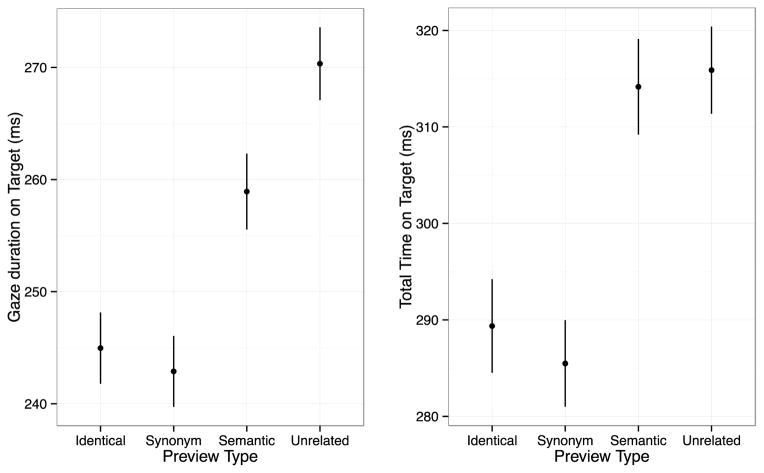

Reading measures on the target word are shown in Table 2 and results of the LMMs on fixation duration measures are reported in Table 3 with the size of the effect (in ms) being represented by the b values. Across all measures there was a significant identical preview benefit such that reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was identical than when it was unrelated (all ts > 3.92). There was a significant preview benefit in the synonym condition; reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was a synonym of the target than when it was unrelated in all measures (all ts > 3.81). Importantly, similar to the N400 findings of Metusalem et al. (2012), there was a significant apparent preview benefit in the semantically associated condition in early reading time measures (first fixation duration, single fixation duration, and gaze duration; all ts > 2.68), but this effect went away in later measures (go-past time: t = 1.33; total time: t < 1). These data suggest that the initial, apparent facilitation provided by the semantically related preview in first pass reading measures went away as the reader had more time to process the precise meaning of the word (Figure 2); we return to this finding in the discussion section.

Table 2.

Means and standard errors (aggregated by subjects) for reading measures on the target across condition.

| Measure | Preview | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Synonym | Semantic | Unrelated | |

| Fixation Duration Measures | ||||

| First Fixation Duration | 223 (4.7) | 222 (4.5) | 228 (4.9) | 239 (4.9) |

| Single Fixation Duration | 229 (5.9) | 226 (4.7) | 235 (6.1) | 248 (5.7) |

| Gaze Duration | 244 (6.5) | 242 (5.5) | 257 (6.3) | 271 (6.3) |

| Go Past Time | 277 (9.0) | 277 (8.7) | 300 (7.7) | 308 (8.3) |

| Total Viewing Time | 289 (9.1) | 285 (8.9) | 313 (9.6) | 317 (7.5) |

| Fixation Probability Measures | ||||

| Fixation Probability | .77 (.02) | .75 (.02) | .77 (.03) | .82 (.02) |

| Regressions out of the Target | .08 (.01) | .09 (.01) | .11 (.01) | .11 (.02) |

| Regressions into the Target | .17 (.02) | .22 (.02) | .23 (.02) | .20 (.02) |

Table 3.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading time measures on the target across condition. Preview benefit refers to the difference in processing between the unrelated condition and either the identical, synonym, or semantically related, separately. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Preview Benefit Comparison | b | SE | |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Fixation Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 239.17 | 5.06 | 47.27 | |

| Identical | −16.98 | 3.83 | 4.44 | |

| Synonym | −17.55 | 4.59 | 3.82 | |

| Semantic | −10.95 | 3.92 | 2.79 | |

| Single Fixation Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 248.71 | 5.84 | 42.57 | |

| Identical | −20.87 | 4.22 | 4.94 | |

| Synonym | −22.64 | 5.25 | 4.31 | |

| Semantic | −13.27 | 4.15 | 3.20 | |

| Gaze Duration | ||||

| Intercept | 270.67 | 6.38 | 42.42 | |

| Identical | −27.85 | 5.52 | 5.05 | |

| Synonym | −29.73 | 5.34 | 5.57 | |

| Semantic | −13.80 | 5.14 | 2.69 | |

| Go-Past Time | ||||

| Intercept | 309.11 | 8.56 | 36.13 | |

| Identical | −32.31 | 7.08 | 4.57 | |

| Synonym | −34.14 | 6.78 | 5.04 | |

| Semantic | −8.92 | 6.70 | 1.33 | |

| Total Time | ||||

| Intercept | 317.84 | 8.58 | 37.05 | |

| Identical | −31.04 | 7.90 | 3.93 | |

| Synonym | −33.67 | 6.94 | 4.85 | |

| Semantic | −5.12 | 7.21 | 0.71 | |

Figure 2.

Means and standard errors for gaze duration (left panel) and total time (right panel) on the target across the four preview conditions in Experiment 1. Note that the scale of the y-axis is different for the two measures.

Fixation probability measures

Results of the LMMs on fixation probability measures are reported in Table 4. It is important to note that any effects across condition observed on fixation probability must be due to processing of the preview (rather than the relationship between preview and target) because the identity of the target has not yet been encountered by the time the fixation/skipping decision is made. Both the identical and synonym preview conditions produced significantly lower probabilities of fixating the target than the unrelated condition (both ps .05), which did not differ from the semantically related condition (p = .29). This effect is likely due to the higher word form cloze probability for the identical and synonym previews (.21 and .25, respectively) than for the other two (both .00). For regressions out of the target, none of the preview contrasts were significant, indicating that subjects were equally likely to make a regression from the target to prior words across conditions (all ps > .07). Readers were less likely to make a regression into the target in the identical condition than in the unrelated condition (p < .05) but neither the semantically related nor the synonym conditions were significantly different from the unrelated condition (both ps > .08), suggesting that any display change led to an increased likelihood of making a regression back to the target, relative to when the word did not change.

Table 4.

Results of the logistic regression model for fixation probability measures on the target across condition. Preview benefit refers to the difference in processing between the unrelated condition and either the identical, synonym or semantically related, separately. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Comparison | b | |z| | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation Probability | ||||

| Intercept | 1.80 | 10.11 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −0.29 | 1.96 | .05 | |

| Synonym | −0.49 | 3.50 | < .001 | |

| Semantic | −0.17 | 1.06 | .29 | |

| Regressions out of the Target | ||||

| Intercept | −2.41 | 13.23 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −.31 | 1.58 | .11 | |

| Synonym | −.38 | 1.73 | .08 | |

| Semantic | .16 | 0.93 | .35 | |

| Regressions into the Target | ||||

| Intercept | −1.61 | 11.56 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −.38 | 2.44 | < .05 | |

| Synonym | .16 | 1.27 | .20 | |

| Semantic | .22 | 1.69 | .09 | |

Overall, these data suggest that first-pass saccade decisions away from an individual word can be affected by expectations about that word based on prior context. Most notably, while in neutral contexts semantic associates did not demonstrate preview benefit (Schotter, 2013), when those same words were embedded in constraining contexts target words were initially read faster (i.e., during first-pass reading) when preceded by a preview of a semantically associated word compared to an unrelated word. Importantly, however, in later reading time measures when full identification of the target word completed, the apparent preview benefit for semantic associates disappeared (Figure 2).

Experiment 2

In order to directly test how contextual constraint influences preview benefit effects in reading, we conducted a second experiment in which both the constraint and preview manipulations were implemented in a within-subjects design.

Method

The method was the same as in Experiment 1 with the following exceptions.

Subjects

Seventy-two undergraduates at the University of California San Diego participated in the experiment. None of them participated in any of the other experiments and were chosen using the same inclusion criteria as Experiment 1.

Materials and Design

Each subject saw stimuli in each of the 8 conditions in a 2 (constraint: high vs. low) x 4 (preview: identical vs. synonym vs. related vs. unrelated) design. Stimuli were identical to those used in Schotter (2013) for the neutral condition and identical to those used in Experiment 1 for the constrained condition.

Results and Discussion

Comprehension accuracy was very high (on average 96%). The same data processing procedure used in Experiment 1 was used in Experiment 2. These data exclusions left 7557 trials (85% of the original data) available for analysis. There were no differences across conditions for gaze duration on the pretarget word (all ts < 1.11), indicating no parafoveal-on-foveal effects (pretarget gaze durations in constrained sentences were 251 ms, 248 ms, 244 ms, and 249 ms and in neutral sentences were 242 ms, 246 ms, 247 ms, and 246 ms in the identical, synonym, semantically related, and unrelated conditions, respectively). Reading time measures on the target word are shown in Table 5. For clarity of exposition (so direct comparisons to the prior experiments are easier) we first report analyses of subset models fit to the four preview conditions fit separately for the different sentence constraint conditions. We address the issue of interactions between the two factors in a separate section, afterward.

Table 5.

Means and standard errors (aggregated by subjects) for reading measures on the target across condition in Experiment 2.

| Measure | Neutral | Constrained | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical | Synonym | Semantic | Unrelated | Identical | Synonym | Semantic | Unrelated | |

| Fixation Duration Measures | ||||||||

| First Fixation Duration | 228 (4.1) | 230 (4.3) | 238 (4.2) | 242 (4.7) | 223 (3.5) | 222 (3.9) | 232 (4.4) | 241 (4.5) |

| Single Fixation Duration | 235 (4.5) | 235 (4.5) | 247 (5.1) | 251 (5.9) | 225 (4.0) | 226 (4.4) | 239 (5.2) | 252 (5.5) |

| Gaze Duration | 262 (5.5) | 260 (6.1) | 276 (6.6) | 276 (6.3) | 252 (5.0) | 249 (5.6) | 263 (5.6) | 276 (5.9) |

| Go Past Time | 293 (7.3) | 295 (8.2) | 310 (9.3) | 309 (8.1) | 276 (6.9) | 277 (7.6) | 287 (7.0) | 311 (8.2) |

| Total Viewing Time | 296 (7.2) | 323 (9.7) | 331 (11) | 326 (8.8) | 272 (6.2) | 293 (7.4) | 300 (7.4) | 306 (7.3) |

| Fixation Probability Measures | ||||||||

| Fixation Probability | .89 (.01) | .86 (.02) | .89 (.01) | .89 (.01) | .79 (.02) | .80 (.02) | .81 (.02) | .83 (.02) |

| Regressions out of the Target | .09 (.01) | .09 (.01) | .09 (.01) | .11 (.01) | .07 (.01) | .08 (.01) | .08 (.01) | .11 (.01) |

| Regressions into the Target | .11 (.01) | .20 (.02) | .19 (.02) | .17 (.01) | .12 (.01) | .16 (.02) | .17 (.02) | .16 (.01) |

Neutral sentence conditions (replication of Schotter, 2013)

Fixation duration measures

Results of the LMMs on fixation duration measures are reported in Table 6. As reported by Schotter, 2013, across all measures there was a significant identical preview benefit such that reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was identical than when it was unrelated (all ts > 2.33). There was an apparent early preview benefit in the synonym condition; reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was a synonym of the target than when it was unrelated in early measures (all ts > 2.64), the effect was marginally significant in go-past time (b = 12.36, t = 1.84), and was not significant in total time (b = 2.89, t = 0.42). The difference between reading time measures in semantically related and unrelated conditions did not significantly differ in any reading time measure (all ts < 1.27). Therefore, these data confirm the preview benefit effects for identical and synonym previews and non-significant preview benefit for semantically related previews reported by Schotter (2013) for words in neutral sentences. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that the pattern of effects is robust even when those sentences are read intermixed with sentences that are highly constraining.

Table 6.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading time measures on the target for neutral and constrained sentences in Experiment 2. Preview benefit refers to the difference in processing between the unrelated condition and either the identical, synonym, or semantically related, separately. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Comparison | Neutral | Constrained | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | |t| | b | SE | |t| | ||

| First Fixation Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 242.46 | 4.79 | 50.58 | 240.96 | 4.58 | 52.63 | |

| Identical | −15.15 | 3.56 | −4.26 | −18.77 | 4.07 | −4.61 | |

| Synonym | −13.15 | 3.96 | −3.32 | −17.73 | 4.40 | −4.03 | |

| Semantic | −4.16 | 3.41 | −1.22 | −8.29 | 3.80 | −2.18 | |

| Single Fixation Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 251.63 | 5.84 | 43.08 | 251.19 | 5.50 | 45.66 | |

| Identical | −16.96 | 4.23 | −4.01 | −25.34 | 4.67 | −5.42 | |

| Synonym | −17.04 | 4.36 | −3.91 | −22.74 | 5.45 | −4.17 | |

| Semantic | −5.32 | 4.21 | −1.26 | −11.67 | 4.63 | −2.52 | |

| Gaze Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 276.30 | 6.98 | 39.61 | 275.87 | 5.92 | 46.63 | |

| Identical | −15.36 | 6.56 | −2.34 | −26.15 | 5.66 | −4.62 | |

| Synonym | −15.97 | 6.03 | −2.65 | −26.17 | 5.21 | −5.02 | |

| Semantic | −1.07 | 5.81 | −.18 | −13.23 | 4.70 | −2.81 | |

| Go-Past Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 309.05 | 8.65 | 35.74 | 310.63 | 8.74 | 35.54 | |

| Identical | −18.63 | 6.91 | −2.70 | −35.13 | 7.18 | −4.90 | |

| Synonym | −12.36 | 6.72 | −1.84 | −34.02 | 7.23 | −4.70 | |

| Semantic | .43 | 6.63 | .06 | −23.83 | 7.08 | −3.37 | |

| Total Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 328.18 | 9.79 | 33.51 | 305.10 | 8.10 | 37.65 | |

| Identical | −31.84 | 6.34 | −5.03 | −32.48 | 6.79 | −4.78 | |

| Synonym | −2.69 | 6.34 | −.42 | −12.09 | 6.53 | −1.85 | |

| Semantic | 2.64 | 6.24 | .42 | −4.76 | 6.05 | −0.79 | |

Fixation probability measures

Results of the LMMs on fixation probability measures are reported in Table 7. Only the synonym preview condition produced significantly lower probabilities of fixating the target than the unrelated condition (p < .05), which did not differ from either the identical or the semantically related condition (both ps > .57). For regressions out of the target, none of the preview contrasts were significant, indicating that subjects were equally likely to make a regression from the target to prior words across conditions (all ps > .38). Readers were less likely to make a regression into the target in the identical condition than in the unrelated condition (p < .005) and were more likely to make a regression into the target in the synonym condition than the unrelated condition (p < .05), but the semantically related condition was not significantly different from the unrelated condition (p = .10).

Table 7.

Results of the logistic regression model for fixation probability measures on the target across condition in Experiment 2. Preview benefit refers to the difference in processing between the unrelated condition and either the identical, synonym or semantically related, separately. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Comparison | Neutral | Constrained | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | |z| | p | b | |z| | p | ||

| Fixation Probability | |||||||

| Intercept | 2.85 | 13.33 | < .001 | 2.15 | 10.30 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −.08 | −.39 | 0.70 | −.32 | −1.74 | .08 | |

| Synonym | −.47 | −2.29 | < .05 | −.26 | −1.38 | .17 | |

| Semantic | −.11 | −.56 | .58 | −.13 | −.67 | .50 | |

| Regressions out of the Target | |||||||

| Intercept | −2.55 | 13.06 | < .001 | −2.47 | 14.24 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −.10 | −.42 | .67 | −.52 | −2.17 | < .05 | |

| Synonym | −.11 | −.45 | .65 | −.46 | −2.15 | < .05 | |

| Semantic | −.21 | −.86 | .39 | −.42 | −1.98 | < .05 | |

| Regressions into the Target | |||||||

| Intercept | −1.92 | 12.87 | < .001 | −1.75 | 15.78 | < .001 | |

| Identical | −.58 | −2.98 | < .005 | −.81 | −3.62 | < .001 | |

| Synonym | .33 | 2.14 | < .05 | −.17 | −1.04 | .30 | |

| Semantic | .27 | 1.62 | .10 | −.07 | −.47 | .64 | |

Constrained sentence conditions (replication of Experiment 1)

Fixation duration measures

As in Experiment 1, across all measures there was a significant identical preview benefit such that reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was identical than when it was unrelated (all ts > 4.60). There was a significant preview benefit in the synonym condition; reading times were significantly shorter on the target when the preview was a synonym of the target than when it was unrelated in all measures (all ts > 4.02) except for total time, where the effect was marginally significant (TVT: b = 12.09, t = 1.85). There was an apparent early preview benefit in the semantically related condition that was significant in all reading time measures (all ts > 2.17) except for total time where the effect completely disappeared (t = 0.79).

Fixation probability measures

There were no significant differences in the probabilities of fixating the target (all ps > .07). Readers were more likely to make regressions out of the target in the unrelated condition than in all other preview conditions (all ps < .05). Readers were less likely to make a regression into the target in the identical condition than in the unrelated condition (p < .001) but there was no difference in regressions into the target between either the synonym condition or the semantically related condition than the unrelated condition (both ps > .29).

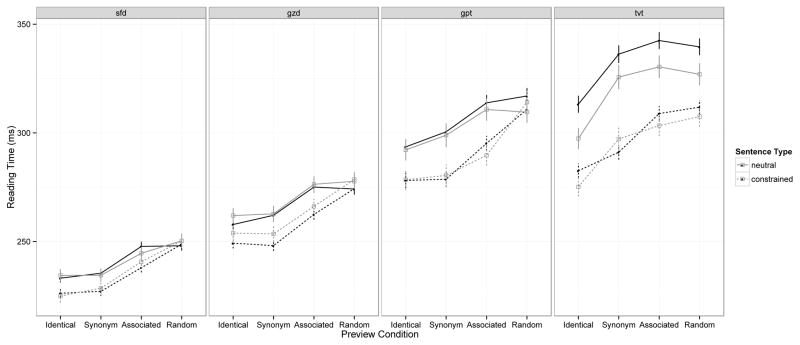

Additional analyses: Tests for interactions between constraint and preview

To better understand the interaction between sentence constraint and parafoveal preview we conducted analyses on the four most theoretically interesting measures. These measures represent the earliest, initial identification stages of processing the word (i.e., single fixation duration and gaze duration) through later, integration and re-analysis stages (i.e., go-past time, and total time). We ran two separate sets of analyses: one using only the data from Experiment 2 since each subject experienced items in every condition and this provides the most straightforward test for an interaction. However, Experiment 2 contained only 72 subjects and 123 items across 8 conditions so we ran additional analyses on the combined the data from three experiments (Schotter (2013) Experiment 2, current Experiment 1, and current Experiment 2) in order to maximize power by taking advantage of all 152 subjects. For both sets of models, we entered the preview contrasts as dummy-coded treatment contrasts with the unrelated condition as the baseline (as in the previous analyses) and entered sentence constraint as a centered predictor. Because only some subjects experienced both levels of sentence constraint (i.e., subjects in current Experiment 2), the random effects structure for subjects contained random intercepts and slopes for preview contrasts only and the random effects structure for items contained intercepts and slopes for both preview contrasts and sentence constraint, entered separately (i.e., without the correlations between them). These interactions are presented in Figure 3 and results of the statistical analyses are presented in Table 8, showing the results of the model with only the Experiment 2 data and the results of the model with the combined data. As seen in Figure 3, the pattern of effects does not change depending on whether only the Experiment 2 data are considered compared to when the data from the combined experiments are used. However, due to the decreased power in the analyses with Experiment 2 data only many of the interactions from those models are not significant while they are significant in the model with the combined data; we note the differences, below.

Figure 3.

Reading time on the target word as a function of preview condition and sentence type, across 4 reading time measures (sfd = single fixation duration, gzd = gaze duration, gpt = go-past time, tvt = total time). Solid lines represent the neutral sentence condition and dashed lines represent the constrained sentence condition. Grey lines with open squares represent the data from Experiment 2 only, black lines with closed circles represent that data combined across three experiments (Schotter (2013) Experiment 2; current study: Experiments 1 & 2).

Table 8.

Results of the linear mixed effects models for reading time measures on the target across conditions in Experiment 2 (left columns) and three combined experiments (right columns). The first four rows in each section represent the intercept (unrelated condition) and preview benefit comparisons averaged across sentence condition. The last four rows represent tests for the effect of sentence constraint on the unrelated condition and the interaction between the preview manipulations and sentence constraint. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Comparison | Experiment 2 data only | Combined Experiments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | |t| | b | SE | |t| | ||

| Single Fixation Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 251.19 | 5.09 | 49.35 | 249.46 | 3.40 | 73.48 | |

| Identical | −20.66 | 3.48 | 5.93 | −19.19 | 2.42 | 7.94 | |

| Synonym | −20.33 | 3.54 | 5.74 | −18.25 | 2.44 | 7.46 | |

| Semantic | −8.20 | 3.27 | 2.51 | −6.32 | 2.18 | 2.90 | |

| Constraint * Unrelated | −0.20 | 4.24 | 0.05 | 1.49 | 3.49 | 0.43 | |

| Constraint * Identical PB | −9.24 | 5.42 | 1.70 | −7.74 | 3.87 | 2.00 | |

| Constraint * Synonym PB | −6.67 | 5.44 | 1.23 | −9.96 | 3.98 | 2.50 | |

| Constraint * Semantic PB | −6.59 | 5.44 | 1.21 | −11.76 | 3.90 | 3.02 | |

| Gaze Duration | |||||||

| Intercept | 275.37 | 5.77 | 47.73 | 272.31 | 4.00 | 68.16 | |

| Identical | −19.96 | 4.41 | 4.53 | −21.37 | 3.11 | 6.87 | |

| Synonym | −20.94 | 4.13 | 5.07 | −20.40 | 2.74 | 7.45 | |

| Semantic | −7.24 | 3.90 | 1.86 | −6.19 | 2.64 | 2.35 | |

| Constraint * Unrelated | −1.10 | 4.67 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 3.88 | 0.15 | |

| Constraint * Identical PB | −9.18 | 6.46 | 1.42 | −9.99 | 4.75 | 2.10 | |

| Constraint * Synonym PB | −11.05 | 6.49 | 1.70 | −15.29 | 4.66 | 3.28 | |

| Constraint * Semantic PB | −12.44 | 6.43 | 1.93 | −14.27 | 4.55 | 3.14 | |

| Go-Past Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 309.30 | 7.48 | 41.37 | 312.87 | 5.43 | 57.58 | |

| Identical | −26.44 | 5.33 | 4.97 | −28.80 | 3.75 | 7.68 | |

| Synonym | −23.23 | 4.75 | 4.89 | −26.11 | 3.61 | 7.23 | |

| Semantic | −12.46 | 5.14 | 2.42 | −10.10 | 3.81 | 2.65 | |

| Constraint * Unrelated | 1.14 | 6.91 | 0.16 | −4.72 | 5.84 | 0.81 | |

| Constraint * Identical PB | −16.73 | 8.96 | 1.87 | −10.47 | 6.65 | 1.57 | |

| Constraint * Synonym PB | −22.36 | 9.01 | 2.48 | −17.48 | 6.46 | 2.71 | |

| Constraint * Semantic PB | −25.76 | 8.94 | 2.88 | −15.08 | 6.64 | 2.27 | |

| Total Time | |||||||

| Intercept | 316.36 | 8.30 | 38.14 | 325.65 | 6.34 | 51.37 | |

| Identical | −31.47 | 5.00 | 6.29 | −30.29 | 4.09 | 7.40 | |

| Synonym | −7.53 | 5.21 | 1.45 | −14.29 | 3.62 | 3.95 | |

| Semantic | −1.77 | 4.72 | 0.37 | −1.27 | 3.51 | 0.36 | |

| Constraint * Unrelated | −23.47 | 6.58 | 3.57 | −21.45 | 5.94 | 3.61 | |

| Constraint * Identical PB | −0.27 | 8.76 | 0.03 | −4.85 | 6.85 | 0.71 | |

| Constraint * Synonym PB | −10.81 | 8.78 | 1.23 | −19.25 | 6.53 | 2.95 | |

| Constraint * Semantic PB | −8.75 | 6.65 | 1.01 | −8.22 | 6.47 | 1.27 | |

The data from single fixation duration and gaze duration are quite similar: the sentence context has no effect on reading times in the unrelated preview condition in either the model with Experiment 2 data or the model with the combined data (all ts < 0.82). For the other three preview conditions (identical, synonym, and semantically related), there were significant interactions with sentence constraint in the model with all data (all ts > 1.99)—the magnitude of these preview benefits were increased in constrained relative to neutral sentences (by approximately 10 ms and 13 ms, for single fixation duration and gaze duration respectively). While the effects were in the same direction and of similar magnitude in the model with only Experiment 2 data, they were not statistically significant (all ts < 1.94).

The pattern of data for go-past time was qualitatively similar to the early measures and was consistent between the model with Experiment 2 data and the model with the combined data; there was no effect of constraint on the unrelated condition (both ts < 0.82) and the preview benefits for the three related preview conditions increased in magnitude by approximately 20 ms in constrained relative to neutral sentence contexts. However, while the interaction was significant for the synonym and semantic preview conditions (all ts > 2.26), it was not significant for the identical preview benefit condition (both ts < 1.88).

Lastly, total time (the latest of these measures because it includes re-reading of the target after first-pass time has ended) shows a different pattern of effects. First, there was a significant effect of sentence context in the unrelated condition in both models (both ts = 3.56)—reading times were about 22 ms shorter in constrained contexts. Second, the significant identical preview benefit in neutral contexts did not significantly increase in magnitude in constrained contexts in either model (t < 0.72), but sentence constraint did interact with the moderately sized synonym preview benefit in neutral contexts so that it doubled in magnitude in constrained contexts; this effect was not significant in the model with only Experiment 2 data (t = 1.23), but was significant in the model with the combined data (t = 2.95). The semantic preview benefit was not significant in neutral contexts and there was no interaction with constraint in either model (both ts < 1.28).

General Discussion

In the present study, we recorded reading times on preview/target words from Schotter (2013) that were embedded in sentences that were moderately constrained so that, rather than a particular word form, the idea shared by the target/synonym was highly predicted (75% of the time). We found that, in contrast to the data reported by Schotter (2013), semantically associated previews yielded faster reading times compared to an unrelated preview during early (first-pass) reading time measures and this apparent preview benefit subsided in late reading time measures. In a second experiment, we replicated both the results from Schotter (2013) and Experiment 1 in a fully within-subjects design, and thus we are quite confident in the data.

These data reveal yet another circumstance under which semantic preview benefit can be observed in English—a formerly elusive finding to report—when the preview/target is embedded in a constraining context. But why might a context that constrains toward a particular idea (e.g., Janet lives on fifth avenue/street…) also lead to faster processing of the target when the preview is only associatively related to the predicted meaning (e.g., suburb) and may not make sense? To explain this, we return to the ideas we raised in the introduction. These data (as well as those reported by Kutas & Hillyard, 1984; Metusalem et al., 2012; and Roland et al., 2012) suggest that sentence constraint leads readers to generate expectations about upcoming words, rather than make a specific, unitary prediction the upcoming word. This interpretation aligns with the idea of pre-activation/anticipation, discussed by De Long et al. (2014) and the suggestion by Smith and Levy (2013) that this pre-activation happens in a qualitatively graded fashion. Thus, even though the previews in the semantically associated condition do not necessarily fit grammatically into the sentence context, they could nonetheless be activated by the comprehension system in anticipation of their role in the general event being described (Elman, 2009). Importantly though, once the system has enough time to identify, process, and attempt to integrate the meaning of these preview words we may observe comprehension difficulty (e.g., increased total time due to more re-reading) if the word does not sensibly fit into the context. How might a process like this occur?

A mechanistic account of the present findings

Recall that one of the assumptions built into the E-Z Reader model is that early oculomotor decisions are “dumb.” Therefore early on in the reading process, the system should not assess whether the word makes sense in great detail. Rather, the system may opportunistically take advantage of any source of information available to hedge a bet that the word will be identifiable in order to time eye movements efficiently. Therefore, decisions about when to move the eyes forward (i.e., at the completion of L1) indicate “hedged bets” that the word in question will be identifiable by the time the eyes move away from it, rather than indicating full recognition of the word. Schotter, Reichle, and Rayner (2014) suggested that the system uses three sources of information to make these oculomotor decisions: prior context, parafoveal preview, and foveal target information. With respect to our data, a constraining prior sentence context contributes one indication that the word should be easy to identify and we observed a different pattern of preview benefit when the sentence was constraining (Experiment 1 and the constrained conditions in Experiment 2) than when the sentence was not constraining (Schotter, 2013 and the neutral conditions in Experiment 2). With respect to the semantic preview benefit observed in the constrained sentences, this may be due to the interaction of semantic expectations generated from the context combined with a lack of assessment or integration to ensure that the interpretation is sensible.

Generally, accounts in which eye movement decisions are based solely on the preview are used to explain skipping decisions (because the target had not yet been displayed/encountered when the decision was made), but seemingly pose a greater challenge when explaining preview benefit effects (i.e., eye movement decisions once the eyes land on the target—after the display has changed)3. To explain this, we return to a discussion of the boundary paradigm. In the introduction, we mentioned that Schotter et al. (2014) proposed a new way of modeling the boundary paradigm—by estimating the proportion of trials on which processing of the upcoming preview word had progressed to the L2 stage in the model. Recall that a corollary of advancing to the L2 stage is that the model also advances to the M1 stage (beginning of saccade programming away from that word). Thus, in those cases, the model estimates that the system can begin programming a saccade away from a word, even before fixating it. Because the model allows for multiple saccade programs to be planned in parallel (E. Reichle, personal communications, December 3, 2014), there should be cases in which the eyes land on the target word, but the saccade program away from that word has already begun and is based on information what was obtained from the preview, rather than the new information from the target.

Importantly, these “dumb” oculomotor decisions are only hypothesized to occur early in the reading process (i.e., in E-Z Reader, this refers to the completion of L1). On this view, once the word is fully recognized, then integration with the sentence occurs and the system should realize that there is a problem. Thus, we observed that the apparent preview benefit for semantically associated words in constrained sentences disappeared in later measures (i.e., those that include regressions; see Figure 2). Moreover, because this realization that the word does not make sense should happen after full word recognition (i.e., after first-pass reading), we would expect that the cost of hedging a bet on the semantically associated word should show up in total time (which includes regressions back to the target after it was left) more strongly than in go-past time (which includes regressions back to words before the target from the target itself). In fact, this is the exact pattern of data we observed: the difference between the semantically associated and unrelated conditions in constrained sentences was larger in go-past time (8 ms in Experiment 1 and 24 ms in Experiment 2) than in total time (4 ms in Experiment 1 and 6 ms in Experiment 2; see Figure 3).

The proposition that early oculomotor decisions are “dumb” and later decisions (i.e., regressions) should be more sensitive to meaning and integration processes suggests that we should observe a dissociation between the pattern of effects in these measures. That is, we would observe an apparent early preview benefit (faster processing of a target with a semantically related compared to unrelated preview), which then leads to a preview cost (or equivalent time to an unrelated preview condition) during later measures that include regressions, if the preview word is nonsensical in the sentence context. Importantly, this should be more likely to happen when the context is moderately constraining, rather than in contexts that are highly constraining (i.e., that make one word obligatory).

Other influences that have demonstrated an “apparent/inappropriate preview benefit,” at least with respect to the measure of skipping, are word length and frequency. For example, an extremely high frequency word like the is skipped very frequently (approximately 50% of the time), even when it is syntactically or semantically inappropriate within the sentence context (Angele & Rayner, 2013; Angele, Laishley, Rayner, & Liversedge, 2014). While neither the semantic spreading activation nor the feature overlap accounts would predict this finding (e.g., it is unclear what are the semantic features of “the” that would overlap with the three-letter verbs used as targets in these studies), an account by which frequency is used (at least for very short three-letter words) as a heuristic to make skipping decisions may be viable. However, the stimuli from these studies are so specific to short words that it is unclear whether these effects generalize.

It may seem counterintuitive that readers should skip (or fixate only briefly) words that are unexpected or do not make sense in the sentence context. Nonetheless, these data suggest that a highly constraining context most likely facilitates reading of, not only the expected word, but also other words that seem as though they should be easy to recognize. This recognizability may be based on several factors, including both length and frequency (Angele & Rayner, 2013; Angele, et al., 2014), and also expectations generated by the context, combined with semantic similarity to the expected meaning (Kutas & Hillyard, 1984; Metusalem et al., 2012; Roland et al., 2012). Thus, in the present study we found that previews that are associatively related to the context being developed led to faster early reading time than previews that were completely unrelated to the context in moderately constrained contexts (current Experiment 1 & current Experiment 2, constrained contexts) even though no such facilitation was observed for semantically associated words in neutral sentence contexts (Schotter (2013) & current Experiment 2, neutral contexts).

Conclusion

The results of the experiments reported here contribute evidence that the presence of an observable semantic preview benefit depends on certain conditions being met but, importantly, we are now beginning to be able to predict when it will and will not be observed. Mainly, semantic preview benefit is unlikely to be observed when reading in a deep orthography, such as English, and there are no cues from the text to support it. This is important to contextualize cross-language differences with respect to semantic preview benefit because languages in which it is observed (e.g., Chinese and German) are more likely to have such cues (see Schotter, 2013; Schotter, Reichle, & Rayner, 2014). However, even when reading in a language with a deep orthography, properties of the text may provide cues that facilitate semantic preview benefit (e.g., visual salience from the preview/target instantiated by capitalizing the initial letter; Rayner & Schotter, 2014; see also Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014). The studies reported here demonstrate another property of the text that may encourage semantic preview benefit: constraint from the prior sentence. Furthermore, these data add evidence to a growing literature showing that sentence context facilitates (at least initially) processing of a group of event-related words, rather than only the most expected word form. Together, these studies suggest that the reading system takes advantage of any source of information available to facilitate reading. For the most part, when experimenters do not manipulate the text during reading, this is advantageous. Importantly, we were able to see the negative consequence of this risky reading strategy in that, when readers had assumed that the preview/target word would be easily recognizable and were incorrect (i.e., in the semantically associated preview condition) later reading measures showed a reading time cost.

Highlights.

The boundary paradigm was used to assess preview benefit with stimuli from Schotter (2013).

Previews/targets were embedded into constrained sentences (Schotter, 2013 used neutral).

Semantic associates showed early preview benefit and late cost in constrained sentences.

Within-subject experiment replicated effects for both neutral and constrained sentences.

Results compatible with E-Z Reader assumption of early oculomotor “hedged bet”.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Atkinson Family Endowment Fund and grant HD065829 from the National Institutes of Health. Portions of these data were presented at the Chinese International Conference on Eye Movements in Beijing, China in May, 2014. We thank Jeff Elman, Denis Drieghe, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on previous drafts.

Appendix

Stimuli used in the experiments. Target words (identical previews) are presented in boldface (not in boldface in the experiments). Columns to the right represent the synonym, semantically related and unrelated previews. Neutral sentences were taken from Schotter (2013) and were used in Experiment 2, constrained sentences were used in Experiments 1 and 2.

| Type | Sentence | Synonym | Semantic | Unrelated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neutral | The dishes are stored below the sink in the kitchen. | under | handy | order |

| 1 | Constrained | It is common knowledge that 90% of an iceberg’s mass lies below the water’s surface. | under | handy | order |

| 2 | Neutral | The sons were quite lousy at doing their chores before dinner. | awful | great | rated |

| 2 | Constrained | I won’t see that movie because everyone said it was really lousy and a waste of money. | awful | great | rated |

| 3 | Neutral | Tim wanted to be more than buddies with Stacey, but she had a boyfriend. | friends | hugging | towards |

| 3 | Constrained | Jen gave Mary a matching bracelet because they’re best buddies and love each other. | friends | hugging | towards |

| 4 | Neutral | At the zoo I saw the giant adult panda eating bamboo leaves. | older | aging | album |

| 4 | Constrained | Tadpoles become frogs as they change from an adolescent stage to an adult stage of life. | older | aging | album |

| 5 | Neutral | Ian auctioned an antique clock to raise money for a charity. | watch | timer | match |

| 5 | Constrained | Jessica was constantly checking time on her large clock so she wouldn’t be late. | watch | timer | match |

| 6 | Neutral | Max had to have the teacher clarify when the homework assignment was due. | explain | discuss | captain |

| 6 | Constrained | The confused students always ask the tutor to please clarify questions on the tests. | explain | discuss | captain |

| 7 | Neutral | Everyone was pleased that the talented chef prepared such a wonderful meal. | cook | food | acid |

| 7 | Constrained | The restaurant recruited a famous chef and it was a great success. | cook | food | acid |

| 8 | Neutral | Sarah tried using curlers on her stubborn straight hair before prom. | rollers | styling | suffice |

| 8 | Constrained | Peg hates straight hair, so instead of a flatiron she uses curlers to style her hair. | rollers | styling | suffice |

| 9 | Neutral | After working out, Shelley felt a sudden acute pain in her calves. | sharp | quick | strip |

| 9 | Constrained | Dogs can locate missing people because their sense of smell is very acute and precise. | sharp | quick | strip |

| 10 | Neutral | The Johnson family fell in love with the beautiful vast backyard at their new home. | huge | open | dogs |

| 10 | Constrained | The sea is relatively unexplored because it’s extremely vast and contains danger. | huge | open | dogs |

| 11 | Neutral | The little girl complained about her upset tummy and asked to skip soccer practice. | belly | torso | daddy |

| 11 | Constrained | Lisa’s new dog loves rolling over for people to rub her fuzzy tummy and fluffy tail. | belly | torso | daddy |

| 12 | Neutral | Tammy noticed many items were left blank when grading the exam. | empty | clear | imply |

| 12 | Constrained | The student didn’t know any answers and left her exam completely blank and failed it. | empty | clear | imply |

| 13 | Neutral | Cops need to be aware of a possible ambush while on the job. | attack | battle | effort |

| 13 | Constrained | While paintballing, Bob’s strategy is to sneak up and secretly ambush the other team. | attack | battle | effort |

| 14 | Neutral | My friends have the same favorite movie that they watch every week. | video | audio | water |

| 14 | Constrained | On Friday, the kids went to Blockbuster to rent a scary movie for their sleepover. | video | audio | water |

| 15 | Neutral | The children must mow the lawn every Friday. | cut | dig | net |