Abstract

Background

Erlotinib is a highly active EGFR kinase inhibitor approved for first-line use in lung cancers harboring EGFR mutations. Anecdotal experience suggests this drug may provide continued disease control following objective progression of disease (PD), however this has not been systematically studied.

Methods

Patients with RECIST-defined PD on three prospective trials of first-line erlotinib in advanced lung cancer were studied retrospectively, comparing progression characteristics of cases with and without EGFR sensitizing mutations. Factors influencing time to treatment change (TTC), defined as the time from PD until start of a new systemic therapy or death, were studied. Rate of tumor progression was assessed by comparing tumor measurements between the PD scan and the preceding scan.

Results

92 eligible patients were studied: 42 with an EGFR sensitizing mutation and 50 without. The EGFR-mutant cohort had a slower rate of progression (p = 0.003) and a longer TTC (p < 0.001). Among EGFR-mutant cancers, 28 (66%) continued single-agent erlotinib following PD and 21 (50%) were able to delay change in systemic therapy for >3 months; only 2 received local debulking therapy during that period. Multivariate analysis of EGFR-mutant cases demonstrated that longer time to progression, slower rate of progression, and lack of new extrathoracic metastases were associated with a longer TTC.

Conclusions

A change in systemic therapy can commonly be delayed in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer objectively progressing on first-line erlotinib, particularly in those with a longer time to progression, a slow rate of progression, and lack of new extrathoracic metastases.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, EGFR mutation, disease progression, erlotinib, time to treatment change

Introduction

First-line treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for patients with lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations has made a transformative impact on the care of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Erlotinib, which has been commercially available in the United States since 2004, is a reversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) which has a 64% response rate (RR) and 9.7 month median progression free survival (PFS) when given first-line to patients with EGFR exon 19 deletions and L858R mutations.1

Anecdotal experience has described the ability to maintain disease control with erlotinib when continuing this drug beyond objective progression on a clinical trial (as defined by the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors [RECIST]).2 Particularly in patients with indolent or asymptomatic progression,3 this has the potential to be an attractive strategy which could delay the use of more toxic cytotoxic chemotherapy. However, the feasibility and safety of this approach is not well described in the literature, leaving many oncologists reluctant to continue erlotinib in the face of radiographic progression. Even on the recently reported ASPIRATION trial, designed to prospectively study the efficacy of erlotinib continuation after objective progression, 46% of patients had their erlotinib immediately stopped at initial objective progression.4 Indeed, in some regions of the world EGFR TKI will no longer be reimbursed by payers if radiographic progression has been identified, whether or not the clinician feels the patient is still benefitting from the drug.

To better define the role of post-progression erlotinib to delay changing systemic therapy, a cohort of patients treated until RECIST progression on three prospective trials of first-line erlotinib administered within the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC) were studied. Our aims were (1) to study the feasibility and effectiveness of delaying treatment change following objective progression using erlotinib, (2) to study this phenomenon in lung cancers without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations as a control cohort, and (3) to identify patient-specific progression characteristics associated with successful post-progression treatment with erlotinib off protocol.

Methods

Patients with NSCLC were studied retrospectively from three prospective trials of first-line erlotinib enrolled between March 2003 and April 2009. All patients were included from a phase II trial of first-line erlotinib in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC (NCT00137800), the results of which have been published previously.5 Second, patients at our centers were included from the erlotinib arm of a multi-centered randomized phase II trial of first-line erlotinib with or without chemotherapy for never/light smokers with lung adenocarcinoma (NCT00126581), also published previously.6 Finally, all patients were included from a phase II trial of first-line erlotinib in women with advanced lung adenocarcinoma (NCT00137839); the results of this trial have also been reported previously.7 Each of these trials included prospective study of response and time to progression (TTP) per RECIST 1.0.2 Patients were deemed eligible for our analysis if they initiated erlotinib on study and continued treatment on study until objective progression of disease (PD) per RECIST, allowing calculation of TTP for each patient. Patients stopping treatment early due to toxicity, withdrawn consent, or death were excluded, therefore no patients were censored from this TPP calculation.

EGFR genotyping was performed when feasible as part of each study, using Sanger-sequencing of exons 18-21 or WAVE-HS, as previously reported.8 As EGFR genotype is a fundamental biomarker for predicting outcome in patients receiving erlotinib, patients unable to complete EGFR genotyping were excluded from this analysis. The remaining patients were divided into two cohorts for comparison: those with a TKI-sensitive EGFR mutation (EGFR-mutant cohort) and those without a TKI-sensitive EGFR mutation (EGFR wildtype cohort).

Patient management after coming off protocol because of objective progression was reviewed, including the systemic and local therapies subsequently received. Because erlotinib has been commercially available in the United States since its initial approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004, patients were able to initiate commercial erlotinib after coming off study at the discretion of the treating provider. The time between coming off study and start of a subsequent systemic therapy or death was calculated and defined as the time until treatment change (TTC), regardless of whether erlotinib was stopped or restarted during this period, or whether local therapy was used. Start of any new systemic therapy, including chemotherapy, investigational therapy, or another EGFR TKI besides erlotinib, was considered treatment change. The time between coming off study because of disease progression and death was calculated and defined as the post-progression survival (PPS).

Progression characteristics were assessed individually for each patient. Rate of progression of measurable disease was assessed by a thoracic radiologist (MN). To focus on the progression rate at time of PD, the summed tumor diameter on the CT scan documenting progression was measured and compared to the summed tumor diameter on the immediate pre-progression scan; this could be a negative value if measurable disease decreased while there was progression in non-measurable disease. Progression imaging was also compared qualitatively to pre-treatment imaging to determine the presence of new sites of extrathoracic metastatic disease (e.g. new development of brain, bone, liver, adrenal, or other metastases). TTC was then studied in the context of progression characteristics which were hypothesized to impact clinical decision making: (1) TTP on initial erlotinib, (2) presence or absence of new extra-thoracic metastases, and (3) rate of progression of the measurable disease (in cm/month).

Results

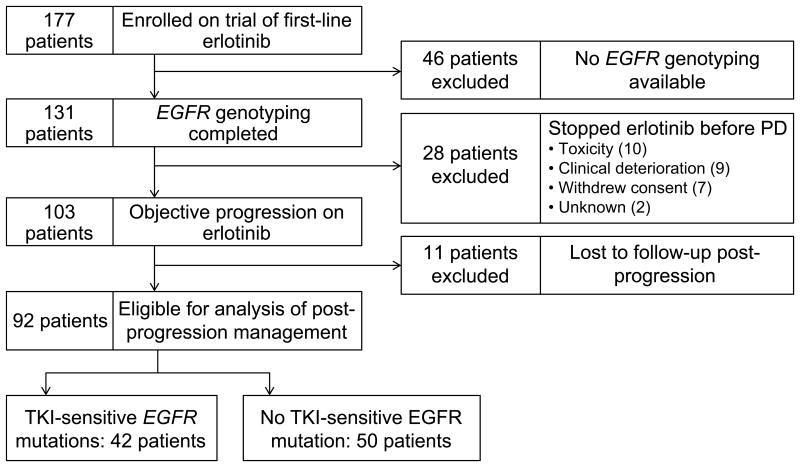

A total of 177 patients from three trials were studied (Figure 1). 74 patients were excluded from analysis: 46 due to incomplete EGFR genotyping and 28 who stopped study drug prior to objective progression on erlotinib. This left 103 patients eligible for our analysis, 11 of whom were lost to follow-up after coming off study and could not be evaluated. The remaining 92 patients were the study population, 42 of whom had tumors positive for a TKI-sensitive EGFR mutation (21 exon 19 deletion, 16 L858R, 5 other), and 50 of whom had tumors wildtype for a TKI-sensitive EGFR mutation.

Figure 1.

Patient cohort for this analysis. Of 184 patients enrolled on three trials of first-line erlotinib, 92 patients were eligible: 42 with TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations and 50 without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations.

The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. As expected, those in the EGFR-mutant cohort were more likely to be never smokers (52% vs 24%, p = 0.01), Asian (10% vs 0%, p = 0.4), and female (88% vs 70%, p = 0.04). The patient population was mostly stage IV at diagnosis (80%) and the histologic subtype of NSCLC was almost entirely non-squamous (98%). As anticipated, patients in the EGFR-mutant cohort had a longer TTP on first-line erlotinib than the EGFR wildtype cohort (14 months vs 1.8 months).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and progression characteristics of patients on study, comparing those with and without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations.

| All patients | Sensitizing EGFR mutation | No sensitizing EGFR mutation | p-value for comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=92 | % | n=42 | % | n=50 | % | ||

| Age: | |||||||

| Median | 69 | 67 | 70 | ||||

| Range | 34-85 | 38-78 | 34-85 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Smoking: | |||||||

| Never | 34 | 37% | 22 | 52% | 12 | 24% | 0.01 |

| Former/current | 58 | 63% | 20 | 48% | 38 | 76% | |

|

| |||||||

| Race: | |||||||

| Asian | 4 | 4% | 4 | 10% | 0 | 0% | 0.04 |

| Non-Asian | 88 | 96% | 38 | 90% | 50 | 100% | |

|

| |||||||

| Gender: | |||||||

| Male | 20 | 22% | 5 | 12% | 15 | 30% | 0.04 |

| Female | 72 | 78% | 37 | 88% | 35 | 70% | |

|

| |||||||

| Stage at diagnosis: | |||||||

| IV | 74 | 80% | 30 | 71% | 44 | 88% | 0.06 |

| I-III | 18 | 20% | 12 | 29% | 6 | 12% | |

|

| |||||||

| Pathology: | |||||||

| Non-squamous | 90 | 98% | 41 | 98% | 49 | 98% | 1.0 |

| Squamous | 2 | 2% | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% | |

|

| |||||||

| Median TTP | 6.9 months | 14 months | 1.8 months | <0.001 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Median TTC | 1.2 months | 3.2 months | 0.6 months | <0.001 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Median PPS | 12.9 months | 18.1 months | 9.9 months | 0.12 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Median rate of PD | 0.3 cm/month | 0.2 cm/month | 0.5 cm/month | 0.003 | |||

|

| |||||||

| PD with new extrathoracic mets: | |||||||

| New met | 15 | 16% | 10 | 24% | 5 | 10% | 0.09 |

| No new met | 77 | 84% | 32 | 76% | 45 | 90% | |

|

| |||||||

| Local therapy prior to new systemic therapy: | |||||||

| Any | 21 | 23% | 10 | 24% | 11 | 22% | 1.0 |

| - Bone radiation* | 9 | 5 | 4 | ||||

| - Brain radiation* | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| - Chest radiation (palliative) | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| - Spine surgery* | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| - Lung resection | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| - Lung SBRT | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| None | 71 | 32 | % | 39 | % | ||

|

| |||||||

| Subsequent systemic therapy post-erlotinib: | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | 55 | 60% | 22 | 52% | 33 | 66% | <0.001 |

| Clinical trial | 15 | 16% | 14 | 33% | 1 | 2% | |

| None (death) | 22 | 24% | 6 | 15% | 16 | 32% | |

TTP: Time to objective progression, TTC: Time until treatment changed, defined as start of a new systemic therapy or death, PPS: Post progression survival, PD: Disease progression, WT: wildtype

One patient received spine surgery followed by bone radiation, and one patient received bone radiation followed by brain radiation

There were some differences in progression characteristics in those with or without a TKI-sensitive EGFR mutation (Table 1). Those in the EGFR-mutant group had a median rate of progression of 0.2 cm/month (range -0.1 to 2.0), slower than the median rate of progression in the EGFR wildtype cohort of 0.5 cm/month (range -0.9 to 4.8)(p = 0.003). The likelihood of new extrathoracic metastases at time of progression was similar in the EGFR-mutant and EGFR wildtype cohorts (24% vs. 10%, p = 0.09). The median post-progression survival (PPS) was numerically longer in EGFR-mutant cancers (18.1 months median, 95% CI 11.3-28.2) than in EGFR wildtype cancers (9.9 months median, 95% CI 6.4-18.8), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.12).

Patients with EGFR-mutant cancers had a significantly longer time until change of systemic therapy compared to those in the EGFR wildtype cohort, with a median TTC of 3.2 months (95% CI 0.5-1.4) versus 0.6 months (95% CI 1.5-8.6) (p < 0.001, Supplemental Figure 1). In the EGFR-mutant cohort, 6 of 42 patients (14%) died before starting a new systemic therapy, while in the EGFR wildtype cohort, 16 of 50 patients (32%) died before starting a new systemic therapy. We therefore conducted a competing risk analysis of TTC adjusting for death as a competing risk: the estimated cumulative incidence of treatment change at 1-month and 3-months based on these models was 26% and 41% for EGFR-mutant cancers and was 52% and 58% for EGFR wildtype cancers. 23% of patients received local therapy during the period prior to change in systemic therapy, and the proportion was similar in the two cohorts despite the prolonged TTC in the EGFR-mutant cohort (Table 1). The majority of local therapies were standard palliative therapies to the bone (9 patients), brain (6 patients), and chest (5 patients); two patients received aggressive debulking therapy of lung lesions (one undergoing resection, one receiving SBRT), both in the EGFR-mutant cohort.

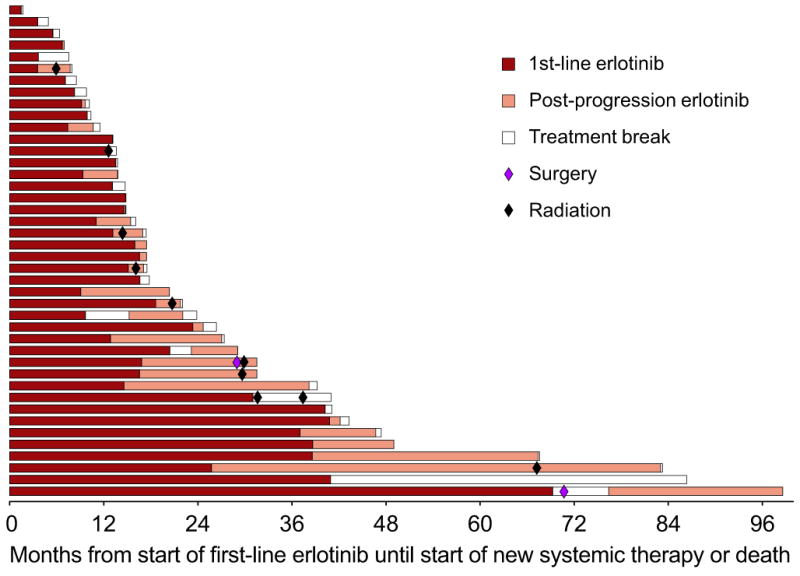

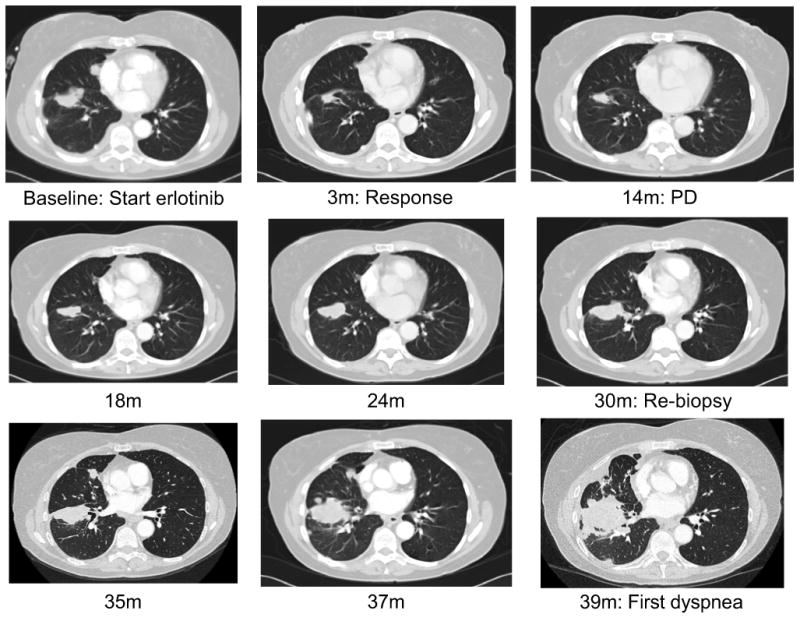

To characterize the prolonged TTC in the EGFR-mutant cohort, management after progression on first-line erlotinib was studied (Figure 2). Of the 42 EGFR-mutant patients, 28 continued single-agent erlotinib (range 0.2-57.5 months) and 14 stopped erlotinib when coming off study for progression. Following erlotinib, 36 of the 42 EGFR-mutant patients went on to receive subsequent systemic therapies; 14 patients (33%) participated in a clinical trial as their next therapy, all involving an EGFR TKI alone or in combination. The remaining 6 patients received no other anti-cancer therapy: 4 had received further post-progression erlotinib, 2 received supportive care only. Of the 42 patients, 21 (50%) delayed initiation of a new systemic therapy for more than 3 months and 9 (21%) for more than 12 months. In one representative case (Figure 3), a patient developed objective progression after 14 months on erlotinib but was asymptomatic with slow progression and no new metastatic sites; the provider continued the patient on post-progression erlotinib for an additional 21 months before starting the patient on a clinical trial.

Figure 2.

On-study erlotinib and post-progression erlotinib in the EGFR-mutant cohort. Each bar represents one patient, beginning at start of first-line erlotinib and ending at time of change in systemic therapy or death. Colored circles represent local therapies used during this period.

Figure 3.

One patient with EGFR-mutant lung cancer who received post-progression erlotinib for a prolonged period following objective progression on a clinical trial of first-line erlotinib. Objective progression occurred after 14 months, but the patient did not develop cancer-related symptoms and did not start a new therapy until 39 months, 2 years after objective progression. m: months, PD: objective progression of disease per RECIST.

As mentioned above, two patients received local debulking therapy. One patient, after nearly 6 years on erlotinib, underwent resection of a 3cm lung tumor that was the only site of progression. After 6 months off erlotinib, she developed multifocal pulmonary recurrence, so the erlotinib was restarted for 2 more years until the patient was lost to follow-up and died. The other patient, after 14 months on erlotinib, underwent SBRT to a 2.8cm lung tumor that was the only site of progression. Erlotinib was restarted for 3 months after which she developed additional intra-thoracic disease and was started on a clinical trial.

To further define the characteristics that impact the decision to delay treatment change in EGFR-mutant lung cancer, the relationship between the three progression characteristics described above and TTC was assessed in a multivariate analysis (Supplemental Table 1). Longer TPP on initial erlotinib, progression without any new extrathoracic metastases, and slower rate of linear progression were all significantly associated with a longer TTC.

Discussion

Genotype-directed targeted therapies are transforming the care of NSCLC, and at the same time are forcing us to reconsider our approach to disease progression on targeted therapy. Many patients, after having dramatic and durable responses to EGFR kinase inhibitors with tolerable side effects, are reluctant to change therapy based on asymptomatic progression on imaging. Indeed, many clinical trials specifically allow continuation of TKI therapy following objective progression if the patient is felt to be having clinical benefit,9 a criteria which is thus far poorly defined. However, experience with this approach has not been systematically assessed. In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of this approach through retrospectively evaluating a cohort of patients with objective progression on first-line erlotinib from three prospective trials. We found that, among patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer who are able to receive erlotinib until objective progression, most are able to delay change in systemic therapy for 3 months or more following objective progression, and 21% can delay change in systemic therapy for more than 12 months. Our findings provide context to the recently reported results of the IMPRESS trial, which showed that, in EGFR-mutant lung cancer with progression on first-line gefitinib, continuing gefitinib when initiating doublet chemotherapy did not improve response rate or PFS.10 While this trial establishes doublet chemotherapy as the standard of care after progression on first-line EGFR TKI, our data suggest that this switch to doublet chemotherapy can potentially be delayed in patients with favorable progression characteristics.

This analysis of a cohort in the United Stated complements the recent report from a prospective study of this approach which enrolled in Asia (ASPIRATION).4 ASPIRATION treated patients with advanced EGFR-mutant lung cancer on first-line erlotinib until objective progression, followed by optional post-progression erlotinib until clinical progression prompted the treating physician to switch therapies. Of 171 patients with objective progression, 78 (46%) were taken off erlotinib at PD while 93 (54%) were continued on erlotinib by their provider. In the subset continued on post-progression erlotinib, the median clinical TTP was 14 months as compared to a median objective TTP of 11 months.

One limitation of the ASPIRATION study is the lack of a control arm. In the study presented here, we found that treatment with erlotinib beyond progression is relatively infeasible in patients without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations, with a median TTC of only 0.6 months after progression on first-line erlotinib. This is presumably because erlotinib is an ineffective therapy in these patients, resulting in a faster rate of progression. Additionally, our study identifies progression characteristics associated with a longer TTC in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer, including a longer TTP on initial erlotinib, lack of new extrathoracic metastases at PD, and slower growth of measurable disease. If prospectively validated, such characteristics might be used by clinicians as they try to determine which patients may be able to delay treatment change using post-progression erlotinib.

The favorable post-progression course we describe in this report was seen despite rare use of local debulking therapies. Although 24% of patients received local therapies, the vast majority of these received conventional palliative radiation such as for brain metastases and symptomatic thoracic or bone lesions. In an uncontrolled single-center report, investigators have previously described the use of local ablative therapy (LAT) for advanced EGFR-mutant or ALK-rearranged lung cancers with oligo-progression on TKI therapy.11 In 25 patients deemed suitable for local therapy, a median PFS of 6.2 months was seen when TKI was restarted after LAT. In our prospective cohort, 11 patients (26%) delayed change in systemic therapy for more than 6 months without use of LAT. In another single-center report, from 184 patients with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI, 18 patients (10%) with favorable outcomes (19 month median TTP on initial TKI) underwent elective non-CNS local therapy resulting a median 22 month TTC.12 In our prospective cohort, 4 patients (10%) delayed change in systemic therapy for more than 22 months without use of elective local therapy. The fact that many patients on our study could delay change in systemic therapy without any use of local intervention raises the possibility that the outcomes seen in this population may be related to the indolent biology of oligo-progressive cancers rather than due to the efficacy of the local therapy itself (such as in the case presented in Figure 3). Before debulking therapies like surgery or high dose radiation become an accepted approach for our patients with metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC and an isolated site of progression, it would be prudent to pursue controlled studies to assess the outcomes with local therapy compared to standard systemic therapy for advanced disease.

The emergence of third-generation mutant-specific EGFR TKIs with antitumor activity against T790M-mediated resistance may change this paradigm of continued TKI beyond progression, given the reported response rates exceeding 50% in patients treated with AZD9291 and CO-1686 and the potential for limited toxicity.13, 14 The EGFR T790M mutation has been associated with indolent growth characteristics in some preclinical and clinical studies compared to other mechanisms of resistance.3, 15 Therefore patients with slow progression on first-line EGFR TKI may wish to pursue a rebiopsy for T790M testing in order to start a third-generation EGFR TKI rather than continuing TKI until clinical symptoms prompt a switch to second-line chemotherapy. Indeed, the availability of clinical trials likely had an impact on the results of this report because 33% of patients in the EGFR-mutant cohort started a second-line clinical trial after first-line erlotinib; if cytotoxic chemotherapy had been their only second-line option, these patients may have delayed treatment change for an even longer period. Importantly, a resistance biopsy for T790M testing is not always technically feasible – for those with indolent progression, it may be safe to continue post-progression TKI and consider attempting a resistance biopsy at a future date.

The findings presented here have potential impact on clinical trial design in NSCLC for patients with EGFR mutations and other oncogenic drivers. Objective progression is currently a standard trial endpoint for regulatory approval of genotype-directed targeted therapies. However, we found that objective progression is not the same as treatment failure, since many patients can continue on targeted therapy after RECIST progression. A similar finding has been described in ALK-rearranged NSCLC, where one study found that more than half of patients with acquired resistance to crizotinib continued the drug for more than 3 weeks after objective progression.16 This may mean that objective progression as currently defined is not optimal for use as a trial endpoint given its lack of clinical applicability. To provide context to a PFS analysis in a randomized trial, it would be useful if trials also reported for each arm progression characteristics like rate of progression, presence of new metastases, and symptom burden at progression.

There are several limitations to this study. While EGFR genotyping to guide first-line therapy was not standard during the period of these trials, EGFR genotype may have been available to investigators for some of these patients and may have influenced their decision to treat with post-progression erlotinib off study. Though this bias may have shortened the TTC for EGFR wildtype patients, our data nonetheless show clearly the feasibility of delaying treatment change in patients with EGFR mutations progressing on erlotinib. There is also potential bias in our use of a novel endpoint, time to treatment change, to demonstrate the feasibility of delaying a new systemic therapy. This endpoint is an intuitive evolution of time to failure of strategy, a composite endpoint like including death, objective progression, or initiation of a new therapeutic agent;17 objective progression is omitted from our definition of time to treatment change as our hypothesis is that this radiographic event is not clinically significant for all patients. Importantly, we are not able to determine from our data whether a delay in treatment change may impact overall survival – indeed, in a patient with symptomatic progression, delay of an effective second-line therapy is likely to have a deleterious effect.

In conclusion, this is the first report to demonstrate the feasibility of delaying change in systemic therapy following RECIST progression on EGFR TKI in a prospectively-assembled cohort of patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer. This study complements the emerging data from the ASPIRATION study, and suggests that post-progression erlotinib can safely be adopted as component of routine lung cancer care. Our data support the recent revision to the NCCN guidelines for NSCLC (Version 4.2015, www.nccn.org), which now recommend continued post-progression EGFR TKI in certain subtypes of progression. The progression characteristics we describe to be associated with delay in treatment change may aid clinicians in their decision-making as they consider continuing EGFR TKI following objective progression on imaging.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Time until treatment change (TTC) by cohort. TTC is defined as the time in months from date off study for objective progression until start of a new systemic therapy or death. TTC was significantly longer in those with than in those without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations (median 3.2 vs 0.6 months, p<0.001).

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P50-CA090578, R01-CA114465, K23-CA157631); by a grant from the Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO; and by the Gallup donor funds.

Footnotes

Summary: Anecdotal experience suggests that some NSCLC patients with progression on erlotinib can have continued disease control without a treatment change. In this analysis, investigators study 92 NSCLC patients with objective progression on first-line erlotinib from 3 clinical trials and demonstrate the potential benefits of delayed treatment change in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer and favorable progression characteristics.

Disclosures: GRO has received consulting fees from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Clovis, and Genentech. MN has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb. BEJ has received consulting fees from Astra-Zeneca and Novartis and honoraria from Chugai. PAJ has received consulting fees from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Clovis, Chugai, and Genentech. BEJ and PAJ are coinventors on a patent held by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for the use of EGFR genotyping, and receive a share of post-market licensing revenue distributed by DFCI. All remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Prior presentation: This material was presented previously in part at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

References

- 1.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Sima CS, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR mutant lung cancer: Distinct natural history of patients with tumors harboring the T790M mutation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:1616–1622. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park K, Ahn M, Yu C, et al. Aspiration: First-line erlotinib until and beyond RECIST progression in Asian patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25:iv426–iv427. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, et al. Phase II clinical trial of chemotherapy-naive patients > or = 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:760–766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jänne PA, Wang X, Socinski MA, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib alone or with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients who were never or light former smokers with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: CALGB 30406 Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2063–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackman DM, Cioffredi L, Lindeman NI, et al. Phase II trial of erlotinib in chemotherapy-naive women with advanced pulmonary adenocarcinoma. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2009;27:8065. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jänne PA, Borras AM, Kuang Y, et al. A Rapid and Sensitive Enzymatic Method for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation Screening. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:751–758. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oxnard GR, Morris MJ, Hodi FS, et al. When Progressive Disease Does Not Mean Treatment Failure: Reconsidering the Criteria for Progression. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104:1534–1541. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok TSK, Wu Y, Nakagawa K, et al. Gefitinib/chemotherap vs chemotherapy in EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer after progresssion on first-line gefitinib: the phase III, randomized IMPRESS study. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, et al. Local Ablative Therapy of Oligoprogressive Disease Prolongs Disease Control by Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Oncogene-Addicted Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2012;7:1807–1814. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182745948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu HA, Sima CS, Huang J, et al. Local Therapy with Continued EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy as a Treatment Strategy in EGFR-Mutant Advanced Lung Cancers That Have Developed Acquired Resistance to EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8:346–351. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827e1f83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janne PA, Ramalingam SS, Yang JCH, et al. Clinical activity of the mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor AZD9291 in patients (pts) with EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014;32:8009. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.08.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sequist LV, Soria JC, Gadgeel SM, et al. First-in-human evaluation of CO-1686, an irreversible, highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor of mutations of EGFR (activating and T790M) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014;32:8010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chmielecki J, Foo J, Oxnard GR, et al. Optimization of Dosing for EGFR-Mutant Non– Small Cell Lung Cancer with Evolutionary Cancer Modeling. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:90ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ou SH, Janne PA, Bartlett CH, et al. Clinical benefit of continuing ALK inhibition with crizotinib beyond initial disease progression in patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25:415–422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chibaudel B, Bonnetain F, Shi Q, et al. Alternative End Points to Evaluate a Therapeutic Strategy in Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Evaluation of Progression-Free Survival, Duration of Disease Control, and Time to Failure of Strategy—An Aide et Recherche en Cancérologie Digestive Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4199–4204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Time until treatment change (TTC) by cohort. TTC is defined as the time in months from date off study for objective progression until start of a new systemic therapy or death. TTC was significantly longer in those with than in those without TKI-sensitive EGFR mutations (median 3.2 vs 0.6 months, p<0.001).