Abstract

Vortioxetine is approved for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder. This open-label extension (OLE) study evaluated the safety and tolerability of vortioxetine in the long-term treatment of major depressive disorder patients, as well as evaluated its effectiveness using measures of depression, anxiety, and overall functioning. This was a 52-week, flexible-dose, OLE study in patients who completed one of three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week vortioxetine trials. All patients were switched to 10 mg/day vortioxetine for week 1, then adjusted between 15 and 20 mg for the remainder of the study, but not downtitrated below 15 mg. Safety and tolerability were assessed on the basis of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), vital signs, laboratory values, physical examination, and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Efficacy measures included the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Severity of Illness, and the Sheehan Disability Scale. Of the 1075 patients enrolled, 1073 received at least one dose of vortioxetine and 538 (50.0%) completed the study. A total of 537 patients withdrew early, with 115 (10.7% of the original study population) withdrawing because of TEAEs. Long-term treatment with vortioxetine was well tolerated; the most common TEAEs (≥10%) were nausea and headache. Laboratory values, vital signs, and physical examinations revealed no trends of clinical concern. The mean Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score was 19.9 at the start of the extension study and 9.0 after 52 weeks of treatment (observed cases). Similar improvements were observed with the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Δ−4.2), the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Severity of Illness (Δ−1.2), and the Sheehan Disability Scale (Δ−4.7) total scores after 52 weeks of treatment (observed case). In this 52-week, flexible-dose OLE study, 15 and 20 mg vortioxetine were safe and well tolerated. After entry into this study, patients continued to show improvement in depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as overall functioning, throughout the treatment period.

Keywords: antidepressant, major depressive disorder, vortioxetine

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a pervasive, persistent, and disabling illness that creates a significant burden on patients, including reduced quality of life, significant somatic as well as psychiatric symptoms, and impaired cognitive function (Kroenke and Price, 1993; Corruble and Guelfi, 2000; Papakostas, 2014). Chronic depression, involving continuous symptoms for a period of at least 2 years, occurs in ~20% of patients and is associated with greater clinical and psychosocial burden, as well as with diminished quality of life (Angst, 1992; Gilmer et al., 2005; Torpey and Klein, 2008). In addition to the significant psychological burden of MDD, a high social and economic burden associated with MDD affects society at large, as well as patients and families. A 2010 World Mental Health Survey conducted by the WHO indicates that the prevalence of MDD in the USA is 8.3% (Kessler et al., 2010).

MDD is characterized by high relapse and/or recurrence rates. As many as 85% of patients treated for MDD will experience recurrence even after long periods of remission (Angst, 1992; Mueller et al., 1999). Given the significant burden associated with MDD, relapse/recurrence prevention is extremely important. International guidelines recommend at least 6 months of maintenance therapy with antidepressants after remission of an episode of depression to prevent relapse and/or recurrence (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH), 2010). Although there are several classes of antidepressants to treat MDD, the efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological maintenance therapies remain limited (Montgomery, 2006).

Vortioxetine at doses of 5, 10, 15, and 20 mg was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2013 for the treatment of adults with MDD, and by the European Commission for the treatment of adults with major depressive episodes. Its mechanism of action is thought to be related to its multimodal activity, which combines direct modulation of serotonin (5-HT) receptor activity and inhibition of the serotonin transporter. In vitro, vortioxetine is a 5-HT3, 5-HT7, and 5-HT1D receptor antagonist, a 5-HT1B receptor partial agonist, a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, and an inhibitor of the 5-HT transporter (Bang-Andersen et al., 2011; Westrich et al., 2012). A number of investigations in vivo have demonstrated that vortioxetine increases extracellular levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, and acetylcholine in the rat forebrain, as well as potentially modulates glutamate neurotransmission by its activity at the various serotonin receptors (Bang-Andersen et al., 2011; Mork et al., 2012, 2013; Pehrson et al., 2013; Pehrson and Sanchez, 2014).

The long-term safety, tolerability, and maintenance of effect of vortioxetine (at doses of up to 10 mg/day) have been previously evaluated in patients with MDD (Baldwin et al., 2012; Florea et al., 2012; Alam et al., 2014). All trials demonstrated that vortioxetine was safe and well tolerated, with no new or unexpected safety signals from long-term use that were not observed during short-term treatment. Improvements in the severity of depressive measures and other health-related quality of life measures were maintained throughout all extension studies, and additional improvements in these measures were achieved.

The long-term safety, tolerability, and maintenance of effect of vortioxetine at higher doses (15 or 20 mg/day) have been evaluated previously (NCT01323478) in a group of 71 patients with MDD who had completed an 8-week lead-in study (Filippov and Christens, 2013). Forty-seven patients (66.2%) completed the 52-week extension trial. Similar to results from lower doses, higher doses of vortioxetine were found to be safe and well tolerated, and the long-term adverse event (AE) profile was similar to that observed during short-term treatment. Patients taking 15 and 20 mg/day dosages of vortioxetine maintained improvements in the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score as well as in health-related quality of life measures throughout the 52-week treatment period. Of the 71 patients who began the extension study, those in remission increased from 23 (32.4%) to 38 (80.9%) patients by the end of the extension study [observed cases (OCs)].

Three short-term double-blind (DB) placebo-controlled studies evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 10, 15, and 20 mg/day vortioxetine were conducted. Study NCT01153009 included 60 mg/day duloxetine as an active reference, in addition to placebo and 15 and 20 mg/day vortioxetine (Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015b). Study NCT01163266 evaluated 10 and 20 mg/day vortioxetine (Jacobsen et al., 2015a). Study NCT01179516 evaluated 10 and 15 mg/day vortioxetine (Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015a). Across the three dose-ranging lead-in studies, 28–55% of study participants with MDD responded to therapy after 8 weeks of treatment [with either 10, 15, or 20 mg/day vortioxetine, 60 mg/day duloxetine (as active reference), or placebo], defined as at least 50% decrease in the MADRS total score from baseline (Jacobsen et al., 2015a; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015a, 2015b). Vortioxetine at 20 mg/day was associated with a significant reduction in the MADRS total score after 8 weeks of treatment. Treatment with vortioxetine was well tolerated in the lead-in studies, with nausea, headache, diarrhea, dizziness, constipation, and vomiting being consistently reported in at least 5% of patients in the vortioxetine treatment groups (Jacobsen et al., 2015a; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015a, 2015b). Patients who completed any one of these three lead-in studies were eligible for participation in this long-term open-label extension (OLE) study.

The primary objective of this study (NCT01152996) was to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of higher dosages of vortioxetine (15 or 20 mg/day) over a period of 52 weeks in patients with MDD. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and the maintenance of therapeutic effect of vortioxetine using various measures of depression, anxiety, and overall functioning.

Methods

Study design

This clinical trial was a long-term, phase III, open-label, flexible-dose extension study conducted in adult patients with MDD at 143 sites within the USA between September 2010 and May 2013. Patients completing one of the three previous short-term efficacy and safety trials (NCT01153009, NCT01163266, or NCT01179516) were eligible to continue treatment for 52 weeks in this OLE study (Jacobsen et al., 2015a; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015a, 2015b). Regardless of dose or medication in the lead-in study, after baseline assessment, all patients were switched to 10 mg/day vortioxetine for the first week of open-label treatment. After the first week, the dose could be adjusted between 15 and 20 mg at the scheduled study visits for the remainder of the study, but the dose was not downtitrated to below 15 mg. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee of each site in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration guidance, the International Conference on Harmonisation, and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent before undergoing any study procedure.

Study participants

Men and women aged between 18 and 75 years were included if they had a primary diagnosis of recurrent MDD (classification code 296.3x), as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. – text revision, at the beginning of the short-term lead-in study. Patients who completed one of the three lead-in trials and for whom continuation of treatment with the study medication for 12 months was clinically indicated according to the judgment of the investigator were included in this long-term extension study. All patients signed a new informed consent form. Sexually active women of child-bearing potential agreed to use appropriate contraception throughout the study and for 1 month thereafter. Patients were excluded from the study if they had been diagnosed with any concomitant psychiatric disorder (e.g. mania, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or any psychotic disorder) during the prior study, were judged by the investigator to have a significant risk of suicide or had a score of 5 or higher on item 10 (suicidal thoughts) of MADRS, were unlikely to be able to comply with the protocol in the opinion of the investigator, had a clinically significant, moderate, or severe ongoing AE related to the study medication administered in the lead-in study, were using or had used disallowed concomitant medication, or were pregnant or lactating. Patients were withdrawn from the study if they experienced an AE that imposed an unacceptable risk to their health or when they were unwilling to continue because of the AE.

Study visits

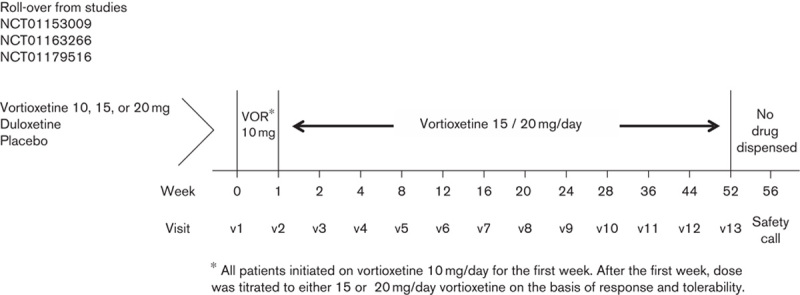

The schematic of the study design is presented in Fig. 1. The completion/final visit of the previous lead-in study served as the open-label baseline (OLB) visit of this long-term extension study and included recording of demographic data, collecting significant medical history, measuring height and body weight, and conducting physical examination, with measurement of vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), and clinical laboratory tests including a pregnancy test when applicable. At every visit during the treatment period, concomitant medication use and vortioxetine return and accountability were recorded. Vortioxetine dose adjustments, if deemed necessary by the investigator, were made, and additional study medication was dispensed.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the study design. VOR, vortioxetine.

Safety measures

Any continuing AE from the lead-in study was recorded at the OLB visit. They were coded by system organ class and preferred term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Version 11.1. AEs, vital signs, and suicidality (using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale [C-SSRS]) were assessed at every visit throughout the treatment period (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 36, and 44), and upon study completion or withdrawal. Other safety and tolerability assessments, including body weight measurement, clinical laboratory tests, physical examination, and ECG, were conducted at regular intervals throughout the treatment period and upon completion of the study. In addition, an adhoc analysis was carried out to assess AEs reported in the initial 14 days of the OLE study by patients who were switched to vortioxetine from either placebo or duloxetine in one of the three short-term lead-in trials.

Efficacy measures

MADRS scores were recorded at the OLB visit and were measured at every visit throughout the treatment period (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 36, and 44), and upon study completion or withdrawal. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) and the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) were scored at OLB, week 4, week 24, and upon study completion or withdrawal. The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was scored at OLB, weeks 12, 24, and 36, and upon study completion or withdrawal.

Outcome variables

The primary objective of this study was to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of higher doses of vortioxetine (15 or 20 mg/day) in patients with MDD. Safety was evaluated on the basis of vital signs and weight, ECGs, clinical laboratory values, suicidality measures, and physical examination. Tolerability assessments were based on a 5% or higher incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) during the study period (up to 30 days after the final dose). All TEAEs were evaluated for severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and causal relationship with the study drug (probable, possible, or not related). The secondary objectives were to assess the effect of vortioxetine on measures of depression, anxiety, and overall functioning, and to evaluate the maintenance of the therapeutic effect of vortioxetine over a period of up to 52 weeks. Secondary endpoints were changed from OLB in MADRS total score, HAM-A total score, SDS total score, and CGI-S score.

Statistical analysis

The ‘Safety Set’ included all patients who were enrolled and received at least one dose of open-label study medication. Antidepressant effect was measured in study participants of the safety analysis set who had at least one post-OLB measurement. Safety and efficacy data have been summarized using descriptive statistics performed with OCs. Statistical analysis was carried out using the SAS System, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient disposition and exposure

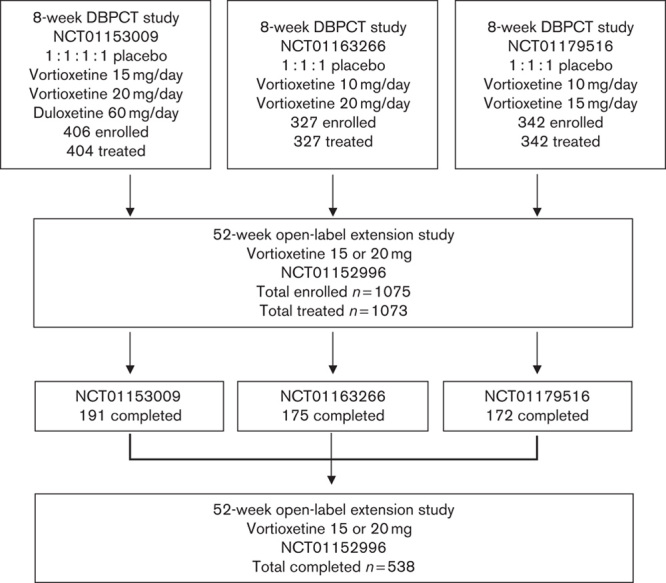

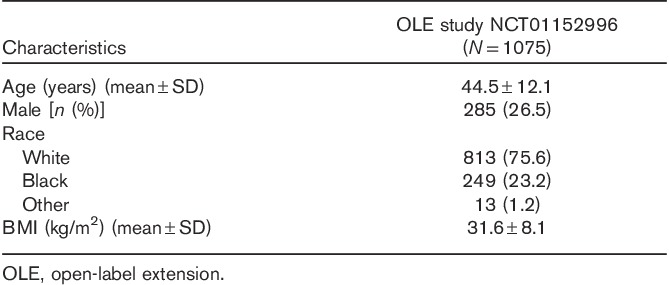

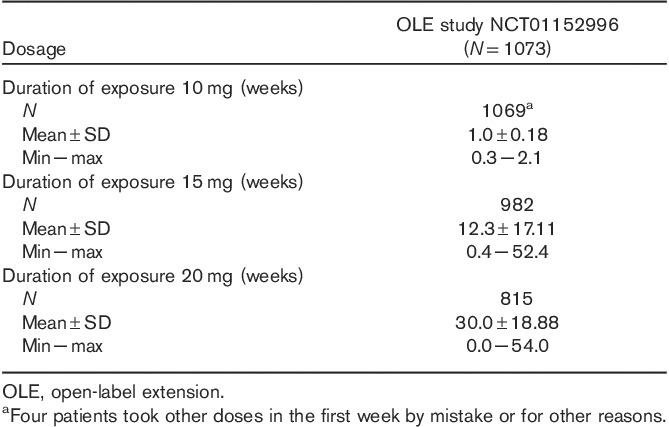

Of the 1075 patients enrolled, 1073 received one or more doses of vortioxetine (Fig. 2). The study participants were predominantly White (including Hispanics; 75.6%) and female (73.5%). Their mean age was 44.5±12.1 years (Table 1). Almost all patients received 10 mg/day vortioxetine during the first week; however, four patients administered other doses during the first week either by mistake or for other reasons. After the first week of treatment, the vortioxetine dosage was increased to 15 or 20 mg/day and could be titrated between 15 and 20 mg/day thereafter, on the basis of patient response and tolerability as judged by the investigator. Of the 1073 patients in the ‘Safety Set’ who received study medication, 666 patients (62.1%) were exposed to vortioxetine for more than 195 days, and 404 patients (37.7%) received vortioxetine for 1 year (Table 2). More than 75% of patients (n=815) received 20 mg vortioxetine for a mean duration of 30.0±18.9 weeks (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Study disposition. DBPCT, double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline clinical and demographic characteristics

Table 2.

Duration of vortioxetine exposure

Table 3.

Duration of vortioxetine exposure by dose

Safety

Of the 1075 patients enrolled, 538 (50.05%) completed the study. No deaths occurred during the study. Among the 537 patients (49.95%) who did not complete the study, withdrawal of consent was the most common reason (n=142, 13.2% of the original study population), followed by TEAEs (n=115, 10.7%) and loss to follow-up (n=112, 10.4%). TEAEs were reported by 854 patients (79.6%), who experienced a total of 3181 events, most of which were characterized by the investigator as mild or moderate in intensity. Approximately half of the TEAEs were judged to be related to study medication. There were 34 serious AEs reported by 29 patients (2.7%), 11 of whom (1.0%) withdrew from the study as a result (Table 4). The following serious AEs were reported by more than one patient: acute cholecystitis (n=2, all not related), breast cancer (n=3, all not related), and suicide attempt (n=3, two cases possibly related). TEAEs reported by at least 5% of patients are shown in Table 5. Weight gain was reported by 6.1% of all patients over the 52-week period, with a mean weight increase of 0.41 kg relative to OLB. Shift analyses of clinical laboratory evaluations including serum chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis revealed no clinically meaningful effect of the drug. The increased risk for hepatotoxicity that was reported with agomelatine treatment was not observed on long-term exposure to vortioxetine (Montastruc et al., 2014). Vital signs, physical examination results, and ECG readings revealed no trends of clinical concern. A prolonged corrected QT interval, such as that reported with some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), was not reported during this extension study (Cooke and Waring, 2013). A dedicated vortioxetine QT/QTc study in healthy male patients indicated that vortioxetine (at doses of up to 40 mg) is unlikely to affect cardiac repolarization (Wang et al., 2013). No deaths occurred during the study. The incidences of TEAEs among patients on the basis of prior treatment assignment or when assessed by vortioxetine dose were similar (Table 6).

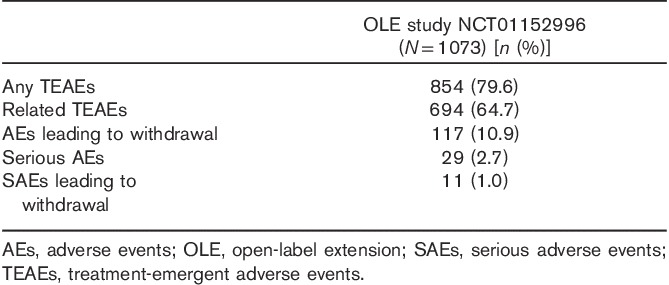

Table 4.

Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events

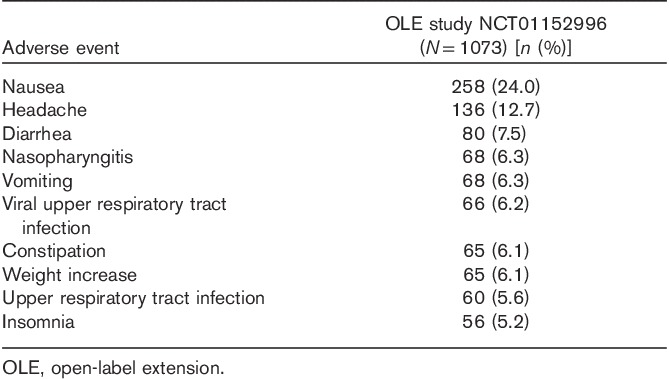

Table 5.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of the study participants

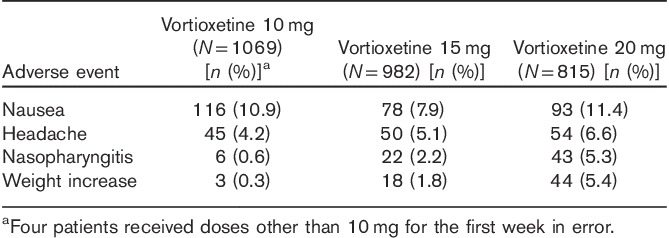

Table 6.

Most frequent adverse events by vortioxetine dose occurring in at least 5% of the study participants

Adhoc analysis of patients who were in a placebo or duloxetine arm during the lead-in study and were switched to vortioxetine in the OLE study revealed that these patients experienced more nausea in the first 14 days compared with those who were previously treated with vortioxetine. The percentage of patients in the placebo arm of the clinical trials NCT01153009, NCT01163266, and NCT01179516 experiencing nausea was 21.6, 21.8, and 19.3%, respectively. The percentage of patients of the duloxetine arm of clinical trial NCT01153009 experiencing nausea was 24.1%. In contrast, the nausea rate for vortioxetine patients during the switch period was 11.3%. After the initial 2 weeks, patients who switched from placebo or duloxetine in the lead-in study experienced similar TEAEs to patients who were in a vortioxetine treatment arm in the lead-in study.

Overall, there was a low incidence of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction (n=5, 1.8%), male sexual dysfunction (n=2, 0.7%), ejaculation delay (n=1, 0.4%), ejaculation disorder (n=1, 0.4%), and ejaculation failure (n=1, 0.4%), among men, and there was one report of sexual dysfunction (0.1%) among women.

Only one patient (0.1% of the ‘Safety Set’) reported active suicidal ideation (with some intent to act, with or without a specific plan) at baseline, and this was deemed possibly related to study medication. During the study, two other patients (0.2%) reported active suicidal ideation that was classified as possibly related to study medication, and one other patient (0.1%) reported an interrupted/aborted suicidal act that was determined to be unrelated to study medication. There were three patients with the serious TEAE of suicide attempt; however, the C-SSRS score documented only one patient with a suicide attempt. This discrepancy can potentially be explained by investigator inconsistency in filling out the C-SSRS form when a suicide attempt was reported. Attempts to reconcile the discrepancy failed.

Effectiveness

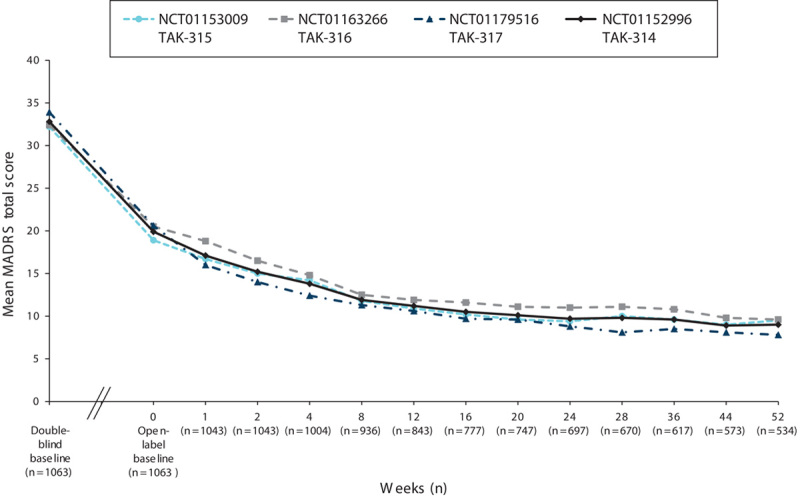

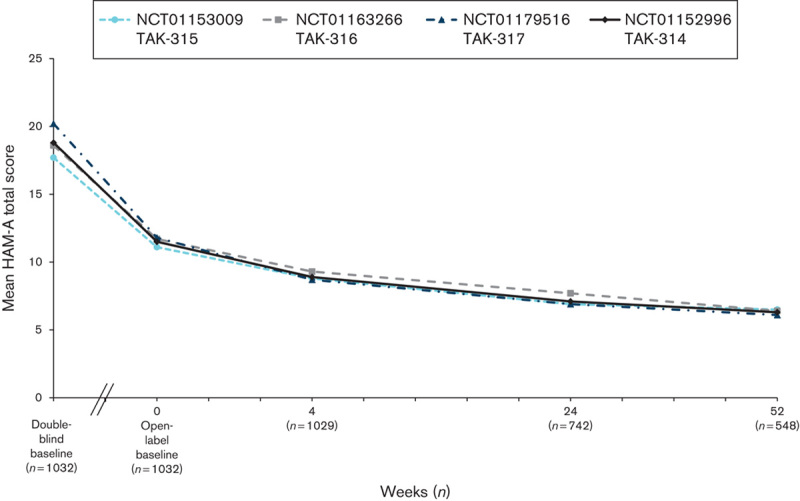

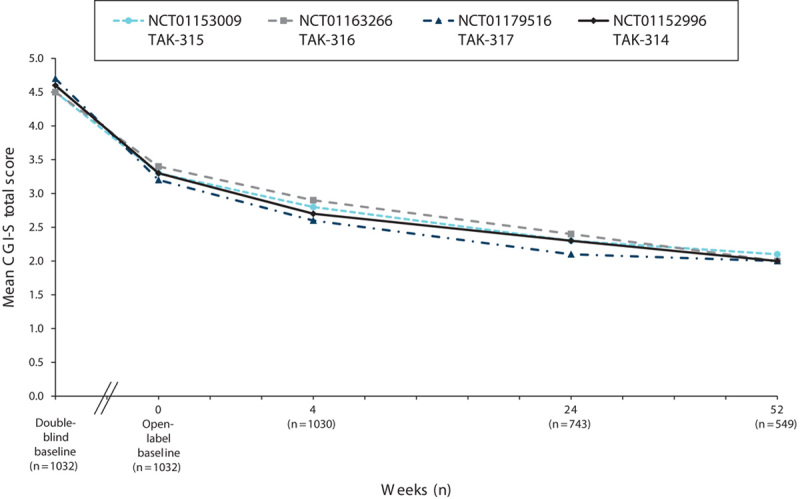

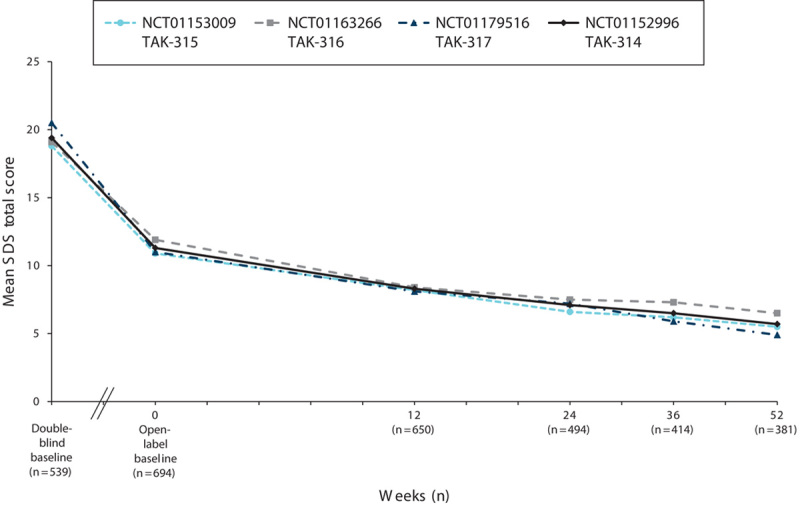

Measures of depression (MADRS), anxiety (HAM-A), global symptoms (CGI-S), and overall functioning (SDS) were assessed at the baseline visit in the short-term DB lead-in study and at the baseline visit in the OLE study. For all the measures of effectiveness, regardless of the study of origin, improvements achieved during the DB period were maintained, and additional improvements were observed during the OLE study. Among the patients in the OLE study, the mean MADRS total score (±SD) decreased from 32.8±4.3 at the start of the initial DB studies to 19.9±10.7 at the OLB, and it was further reduced during the OLE study to 9.0±9.0 by week 52 (OC; Fig. 3). A similar improvement in measures of anxiety was observed during the extension study. The mean HAM-A total score, which decreased from 18.8±5.5 at the start of the initial DB studies to 11.5±6.6 at the start of the OLE study, further decreased to 6.3±5.8 (OC) by week 52 (Fig. 4). The improvements seen in the short-term study for CGI-S were maintained, and improvement continued in the long-term study. The mean CGI-S total score decreased throughout the study from 4.6±0.6 at the start of the DB studies to 3.3±1.2 at the start of the OLE study. At week 52, the mean score was 2.0±1.1 (OC), corresponding to a change from the OLE baseline of −1.2±1.3 (Fig. 5). The mean SDS total score decreased during the OLE study from 11.3±7.7 at OLB to 5.7±6.4 (OC) at week 52 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Mean MADRS total scores by study visit for the OLE study (NCT01152996) and three DB feeder studies (OC). DB, double blind; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; OC, observed case; OLE, open-label extension.

Fig. 4.

Mean HAM-A total scores by study visit for the OLE study (NCT01152996) and three DB feeder studies (OC). DB, double blind; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; OC, observed case; OLE, open-label extension.

Fig. 5.

Mean CGI-S total scores by study visit for the OLE study (NCT01152996) and three DB feeder studies (OC). CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Scale-Severity of Illness; DB, double blind; OC, observed case; OLE, open-label extension.

Fig. 6.

Mean SDS total scores by study visit for the OLE study (NCT01152996) and three DB feeder studies (OC). DB, double blind; OC, observed case; OLE, open-label extension; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

The long-term effectiveness of vortioxetine therapy was also demonstrated in terms of patients who were defined as treatment responders (patients with a ≥50% decrease in MADRS total score from baseline). At OLB, 142 of 1043 patients (13.6%) were responders on the basis of the original DB baseline MADRS total score; this number increased to 317 of 534 patients (59.4%) at week 52 (OC). Data collected at the final visit, which included 1063 patients and accounted for the response of patients in the safety analysis set who had at least one post-OLB efficacy measurement but who may have dropped out of the clinical trial at any point before 52-week completion, showed that the total number of responders was 502 (47.2%; OC). The numbers and percentages of patients who were considered in remission (patients with MADRS total score≤10) increased from 304 of 1043 patients (29.1%) at OLB to 346 of 534 patients (64.8%) at week 52 (OC). At the final visit, accounting for all patients enrolled, the total number of patients in remission was 580/1063 (54.6%; OC).

Discussion

In this phase III, flexible-dose, open-label, multicenter extension study, 15 or 20 mg vortioxetine was used for 52 weeks for the treatment of patients with MDD. The primary objective was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of long-term treatment with vortioxetine at higher doses, and results indicate that such treatment is well tolerated at both doses. Overall, 50.05% of the 1075 patients enrolled completed the OLE study. The withdrawal rate because of AEs in this OLE study was 10.9%. The majority of AEs were characterized as mild or moderate, and the long-term AE profile of vortioxetine was similar to that observed during the short-term lead-in efficacy studies. Although patients who switched from placebo or duloxetine to vortioxetine experienced nausea more frequently during the first 14 days of the OLE study, after 2 weeks the TEAEs experienced by this subset of patients were similar to those experienced by patients who were in a vortioxetine treatment arm in the lead-in studies. The difference in nausea rates is likely because individuals already exposed to vortioxetine in the lead-in study (as opposed to those who switched treatments in the OLE) were acclimated to the treatment. Two recently published clinical trials in which MDD patients previously treated with SSRIs were directly switched to vortioxetine reported that the incidence of nausea associated with switching to vortioxetine was less in patients who had been previously treated with an SSRI (Montgomery et al., 2014; Jacobsen et al., 2015b).

There were no TEAEs reported during the extension period that were not already identified in other OLE studies of vortioxetine at lower doses (≤10 mg/day; Baldwin et al., 2012; Florea et al., 2012; Alam et al., 2014). Serum chemistry analysis, hematological analysis, urinalysis, assessment of vital signs, physical examination, and ECG revealed no trends of concern associated with long-term vortioxetine use. There were no differences observed in measures of safety among patients according to the lead-in study of origin. No deaths occurred during the OLE study.

Suicide-related AEs were monitored in the current OLE study using the C-SSRS. There were few patients with suicidal ideation or behavior during the study. Spontaneous reporting of related AEs indicated a low rate of sexual dysfunction as a side effect of long-term vortioxetine treatment. Sexual dysfunction was not assessed with the use of a specific scale in this study.

On the secondary objective of evaluating the effectiveness of long-term treatment with vortioxetine at higher doses, results indicate that improvements in depressive symptoms seen in the short-term lead-in studies were maintained and additional improvement was observed throughout the extension period. Efficacy gains were observed for all patients irrespective of prior treatment group. By the end of the study, both the number of MADRS responders and those in remission (MADRS≤10) had increased. Vortioxetine showed a positive effect on reducing anxiety symptoms, as measured by the HAM-A total score. Patients also maintained improvement in global symptoms over the 52-week treatment period, as indicated by the improvements in the CGI-S score throughout the OLE study.

Patient-reported overall functioning, as assessed by the SDS, indicated that patients experienced decreased impairment over the course of the treatment. Improvement that occurred during the lead-in studies was sustained, with further improvement in scores throughout the OLE study period.

The open-label design limits the conclusions that can be drawn, as only patients who completed the DB lead-in studies were eligible for enrollment in this study, which lacked a comparator or placebo control (NCT01153009, NCT01163266, and NCT01179516).

Conclusion

In this phase III, 52-week, open-label, flexible-dose, multicenter extension study, vortioxetine was safe and well tolerated at dosages of 15 or 20 mg once daily. No new TEAEs were observed during the extension period that were not present during the short-term lead-in studies, and all reported TEAEs in this study were comparable to those observed in previously reported phase III studies of vortioxetine at lower doses. Improvements in depression, anxiety, and global symptoms achieved during the lead-in studies were further improved over 52 weeks of treatment, as measured by MADRS, HAM-A, and CGI-S scores. Patient functioning showed continued improvement on the basis of the mean total SDS score.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd as part of a joint clinical development program with H. Lundbeck A/S. Assistance with writing and manuscript preparation was provided by Susan Martin, PhD, and Philip Sjostedt, BPharm, of The Medicine Group and was funded by the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd and H. Lundbeck A/S.

Paula Jacobsen was the Clinical Scientist responsible for this study and is an employee of Takeda Development Center Americas Inc. Linda Harper is a psychiatrist and an employee of CNS Healthcare Inc., Orlando, FL, USA. Lambros Chrones is a clinical psychiatrist who serves as the Global Safety Lead for vortioxetine as Associate Medical Director in Pharmacovigilance at Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. Serena Chan is a clinical statistician who served as the study statistical lead for vortioxetine during her tenure as the Senior Statistician in Analytical Science at Takeda Development Center Americas Inc. Atul R. Mahableshwarkar is a psychiatrist and an employee of Takeda Development Center Americas Inc.; he was the responsible Medical Officer for the study.

P.L.J. was involved in protocol development, study oversight, data cleaning and interpretation, and planning, writing, reviewing, and revising the manuscript. L.H. was a clinical investigator in the study and participated in reviewing the study results, and in reviewing and revising the manuscript. L.C. was involved in data cleaning and interpretation and participated in planning, reviewing, and revising the manuscript. S.C. was involved in protocol development, study oversight, planning and carrying out statistical analyses, data cleaning and interpretation, and reviewing and revising the manuscript. A.R.M. was involved in protocol development, providing medical oversight to the study, data cleaning and interpretation, and planning, writing, reviewing, and revising the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Paula L. Jacobsen and Atul R. Mahableshwarkar are employees of Takeda Development Center Americas. At the time of this study, Lambros Chrones and Serena Chan were employees of Takeda Development Center Americas. Linda Harper has received honoraria as a speaker for Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Alam MY, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, Serenko M, Mahableshwarkar AR. (2014). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in major depressive disorder: results of an open-label, flexible-dose, 52-week extension study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 29:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J.Montgomery S, Rouillon F. (1992). How recurrent and predictable is depressive disorder? Long-term treatment of depression; perspectives in psychiatry Vol 3. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS, Hansen T, Florea I. (2012). Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in the long-term open-label treatment of major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 28:1717–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang-Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jørgensen M, Smith G, Frederiksen K, Jensen KG, et al. (2011). Discovery of 1-[2-(2,4-dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine (Lu AA21004): a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Med Chem 54:3206–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MJ, Waring WS. (2013). Citalopram and cardiac toxicity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corruble E, Guelfi JD. (2000). Pain complaints in depressed inpatients. Psychopathology 33:307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippov G, Christens P. (2013). P.2.b.011 Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) 15 and 20 mg/day: open-label long-term safety and tolerability in major depressive disorder (abstract). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23:S325. [Google Scholar]

- Florea I, Dragheim M, Loft H. (2012). P.2.c.010 The multimodal antidepressant Lu AA21004: open-label long-term safety and tolerability study in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 22:S255–S256. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer WS, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Luther J, Howland RH, et al. (2005). Factors associated with chronic depressive episodes: a preliminary report from the STAR-D project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112:425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PL, Mahableshwarkar A, Serenko M, Chan S, Trivedi M. (2015a). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine 10 mg and 20 mg in adults with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PL, Mahableshwarkar AR, Chen Y, Chrones L, Clayton AH. (2015b). A randomized, double-blind, head-to-head, flexible-dose study of vortioxetine versus escitalopram on sexual functioning in adults with well-treated major depressive disorder experiencing treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Shahly V, Bromet E, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, et al. (2010). Age differences in the prevalence and co-morbidity of DSM-IV major depressive episodes: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Depress Anxiety 27:351–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Price RK. (1993). Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med 153:2474–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, Serenko M, Chen Y, Trivedi M. (2015a). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 2 doses of vortioxetine in adults with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, Serenko M, Trivedi MH. (2015b). A randomized, double-blind, duloxetine-referenced study comparing efficacy and tolerability of 2 fixed doses of vortioxetine in the acute treatment of adults with MDD. Psychopharmacology (Berl) [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montastruc F, Scotto S, Vaz IR, Guerra LN, Escudero A, Sáinz M, et al. (2014). Hepatotoxicity related to agomelatine and other new antidepressants: a case/noncase approach with information from the Portuguese, French, Spanish, and Italian pharmacovigilance systems. J Clin Psychopharmacol 34:327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA. (2006). Why do we need new and better antidepressants? Int Clin Psychopharmacol 21 (Suppl 1):S1–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Nielsen RZ, Poulsen LH, Häggström L. (2014). A randomised, double-blind study in adults with major depressive disorder with an inadequate response to a single course of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor treatment switched to vortioxetine or agomelatine. Hum Psychopharmacol 29:470–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørk A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, Nielsen SM, Zhong H, Lassen AB, et al. (2012). Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørk A, Montezinho LP, Miller S, Trippodi-Murphy C, Plath N, Li Y, et al. (2013). Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a novel multimodal antidepressant, enhances memory in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 105:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller TI, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Endicott J, Coryell W, et al. (1999). Recurrence after recovery from major depressive disorder during 15 years of observational follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 156:1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) (2010). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists. [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas GI. (2014). Cognitive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder and their implications for clinical practice. J Clin Psychiatry 75:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson AL, Sanchez C. (2014). Serotonergic modulation of glutamate neurotransmission as a strategy for treating depression and cognitive dysfunction. CNS Spectr 19:121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrson AL, Cremers T, Bétry C, van der Hart MG, Jørgensen L, Madsen M, et al. (2013). Lu AA21004, a novel multimodal antidepressant, produces regionally selective increases of multiple neurotransmitters – a rat microdialysis and electrophysiology study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23:133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torpey DC, Klein DN. (2008). Chronic depression: update on classification and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 10:458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Nomikos GG, Karim A, Munsaka M, Serenko M, Liosatos M, et al. (2013). Effect of vortioxetine on cardiac repolarization in healthy adult male subjects: results of a thorough QT/QTc study. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2:298–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrich L, Pehrson A, Zhong H, Nielsen SM, Frederiksen K, Stensbol TB, et al. (2012). In vitro and in vivo effects for the multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) at human and rat targets. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 16:47. [Google Scholar]