Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the HSD17B1 gene polymorphisms in the risks of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma by meta-analysis. A comprehensive electronic search was conducted in PubMed, Medline (Ovid), Embase, Weipu, Wanfang and CNKI. The pooled ORs were performed using the Revman 5.2 softerware. 8 case-control studies were included: 3 were about endometrial cancer, 4 were about endometriosis and 1 was about uterine leiomyoma. The result showed no significant association between HSD17B1 rs605059 gene polymorphisms and risks of endometrial cancer (AA vs. AG+GG: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.94-1.32; AA+AG vs. GG: OR = 1.79, 95% CI = 0.42-7.52; AG vs. AA+ GG: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.76-1.00; AA vs. GG: OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 0.62-3.30; A vs. G: OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.91-1.11) or endometriosis (AA vs. AG+GG: OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.75-1.32; AA+AG vs. GG: OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 0.92-3.25; AG vs. AA+ GG: OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.00-1.53; AA vs. GG: OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 0.79-2.97; A vs. G: OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.90-1.68). No association was found in a subgroup analysis based on Asian ethnicity for endometriosis. This meta-analysis suggested that HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms were not associated with the risks of endometrial cancer and endometriosis. Further studies are needed to validate the conclusion and clarify the relationship between HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of uterine leiomyoma.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, endometriosis, leiomyoma, HSD17B1, polymorphism, meta-analysis

Introduction

Estrogen has been reported to be one pivotal risk factor for the development of many uterine diseases like endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma [1-3]. This is validated by the fact that women of reproductive age and postmenopausal women under estrogen replacement therapy are the most susceptible group of people for the three types of diseases [4,5]. Therefore, it is considered that discrepancies on the process of estrogen production and metabolism should play a role in the development of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma.

The 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD17B) is important in the synthesis and metabolism of sex steroid hormones and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (HSD17B1s) is the most common subtype [6,7]. It is an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of estrone to the more biologically active estradiol in the final step of estrogen synthesis [8]. The encoding gene of HSD17B1 is located on chromosome 17q12-q21, and the protein is expressed in the ovaries, placenta, testis, endometrium, malignant and normal breast epithelium, and prostatic cancer cells [9-11]. Thus, it is assumed that estrogen-metabolizing gene HSD17B1 polymorphisms, which can potentially cause alterations in their biological function, should contribute to the susceptibility of individuals to hormone-related diseases. One type of HSD17B1 gene polymorphisms is rs605059. It is located in exon 6 (1954A/G) that leads to an amino acid change from serine to glycine at position 312 [12,13]. Several studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between HSD17B1 rs605059 gene polymorphisms and risks of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma. However, the results were inconclusive due to different sizes of samples and participant characteristics. Thus, we performed a meta-analysis of currently relevant studies to investigate the relationships between HSD17B1 rs605059 gene polymorphisms and risks of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma.

Materials and methods

Literature and search strategy

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted in PubMed, Medline (Ovid), Embase, Weipu, Wanfang and CNKI for studies published from January 1995 to April 2015. The following search query was used: “uterine”, “endometrial cancer”, “endometriosis”, “leiomyoma”, “polymorphism”, “HSD17B1”, “HSD17β1”, “17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase”, “variant” and “mutation”. The search was updated every week until April 10, 2015.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles fulfilling the following criteria were included: (i) analyzed HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms in uterine diseases (endometrial cancer, endometriosis, leiomyoma), (ii) provided sufficient data in both case and control groups to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% CIs, (iii) case-control studies. When duplicate data were present in different articles, only the latest one would be considered. Meanwhile, articles that didn’t fulfill the criteria mentioned above were excluded.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently reviewed all potential studies. The following items were extracted: first author, year of publication, ethnicity, risk factors, diagnostic standard, features of control, target genotypes, genotyping methods, participant numbers, and genotype distributions in cases and controls. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third investigator until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Pooled ORs and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated to estimate the strength of the association between the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risks of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and leiomyoma. SNPs were considered as binary variables. We estimated the risks of homozygous mutants (AA vs. AG+GG), heterozygous and homozygous mutants (AA+AG vs. GG) and heterozygous mutants (AG vs. AA+GG). We then compared the variant genotype AA with the wild type GG homozygote (AA vs. GG). We also assessed the risks of variant gene A alone. (A vs. G). Heterogeneity assumptions were checked using the Higgins I2 test. If heterogeneity did not exist (I2 < 50%), a fixed-effects model was applied otherwise a random-effects model was used. The Z test was performed to determine the significance of the pooled ORs where P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The presence of publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting the asymmetry in funnel plots. All analyses were performed using the Revman 5.2 softerware (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen).

Results

Search results

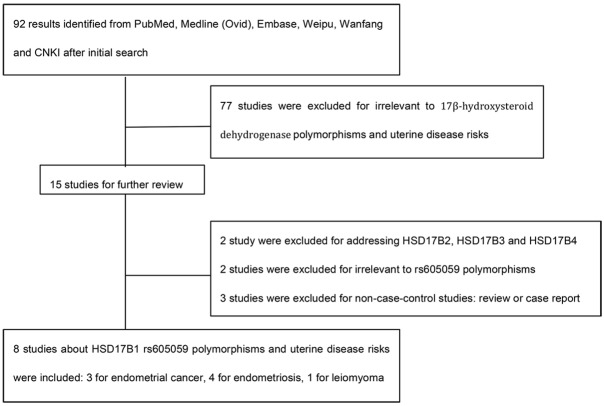

92 results returned after the initial search. In our further review, 77 studies were excluded for irrelevant to 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase polymorphisms and uterine disease risks based on titles and abstracts. Among the remaining 15 articles, 2 studies were excluded for addressing HSD17B2, HSD17B3 and HSD17B4 polymorphisms instead of HSD17B1 variants [14,15]; 2 studies reported HSD17B1 polymorphisms like rs2006200, rs2071046 and rs597255 other than rs605059 [16,17]; 3 studies were excluded for non-case-control studies [18-20]. Therefore, we enrolled 8 articles in this meta-analysis (Figure 1) [21-28].

Figure 1.

The flow chart of study selection.

Study characteristics

Among the 8 enrolled case-control studies, 3 were about endometrial cancer, 4 were about endometriosis and 1 was about uterine leiomyoma. 7 of the total 8 studies reported the numbers of HSD17B1 rs605059 gene variants AA, AG and GG in both case and control groups separately. One study only reported the numbers of heterozygous mutants AG and we failed to get any response from the corresponding authors to retrieve the numbers of homozygous mutants [24]. 6 of the total 8 studies demonstrated the patients’ ethnicity as Caucasian or Asian while the other 2 failed to mention any information about the races (Table 1). Possible variables among participants that might affect the odds ratios were also discussed including age, body mass index, history of diabetes and hypertension, hormone therapy history, family history of cancers, smoking, alcohol consumption and menopausal status (Table 2).

Table 1.

The characteristics and genotype distributions of included studies

| First author | Year | Ethnicity | Disease type | Case number | Control number | Case | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| GG | AG | AA | GG | AG | AA | ||||||

| Ashton | 2010 | Caucasian | Endometrial cancer | 191 | 290 | 43 | 84 | 64 | 52 | 147 | 91 |

| Dai | 2006 | Asian | Endometrial cancer | 1031 | 1019 | 380 | 465 | 186 | 358 | 487 | 174 |

| Setiawan | 2003 | N/A | Endometrial cancer | 219 | 664 | 54 | 96 | 69 | 167 | 316 | 181 |

| Wu | 2012 | Asian | Endometriosis | 121 | 171 | N/A | 61 | N/A | N/A | 87 | N/A |

| Wang | 2012 | Asian | Endometriosis | 300 | 337 | 81 | 166 | 53 | 94 | 175 | 68 |

| Tsuchiya | 2005 | Asian | Endometriosis | 75 | 57 | 13 | 40 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 14 |

| Lamp | 2011 | N/A | Endometriosis | 150 | 199 | 23 | 84 | 43 | 54 | 93 | 52 |

| Cong | 2012 | Asian | Leiomyoma | 121 | 217 | 15 | 66 | 40 | 51 | 111 | 55 |

Table 2.

Comparison of possible risk factors between cases and controls

| First author | Age | BMI | Diabetes | Hypertension | Hormone therapy | Personal or relative history of cancer | Smoking | Alcohol | Menopausal statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashton | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | YES | N/A |

| Dai | NO | YES | N/A | N/A | NO | Yes | N/A | N/A | YES |

| Setiawan | NO | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO |

| Wu | NO | NO | N/A | N/A | NO | N/A | N/A | N/A | NO |

| Wang | YES | NO | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NA | NA |

| Tsuchiya | NO | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NO |

| Lamp | YES | YES | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | YES | NO | YES |

| Cong | NO | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NO | N/A | NO |

NO: no difference presented between cases and controls; YES: significant difference presented between cases and controls.

Quantitative data analysis

Table 3 showed the pooled odds ratio of HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms in the risk of endometrial cancer and endometriosis. 3,414 participants were analyzed for the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometrial cancer. We found no significant association using 5 different genotype or allele comparisons: AA vs. AG+GG, AA+AG vs. GG, AG vs. AA+ GG, AA vs. GG and A vs. G (AA vs. AG+GG: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.94-1.32; AA+AG vs. GG: OR = 1.79, 95% CI = 0.42-7.52; AG vs. AA+ GG: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.76-1.00; AA vs. GG: OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 0.62-3.30; A vs. G: OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.91-1.11). Fixed-effects model or random-effects model was chosen according to Higgins I2 test. When heterogeneity did not exist (I2 < 50%), a fixed-effects model was applied otherwise a random-effects model was used. Z values and P values were also calculated to assess the pooled ORs.

Table 3.

Summary of different comparative results

| Disease type | Genotypes | Overall&subgroup | Participants | OR (95% CI) | Z value | P value | I2 (%) | Effect Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial cancer | AA vs. AG+GG | Overall | 3,414 | 1.11 (0.94, 1.32) | 1.25 | 0.21 | 0 | Fixed |

| AA+AG vs. GG | Overall | 3,414 | 1.79 (0.42, 7.52) | 0.79 | 0.43 | 98 | Random | |

| AG vs. AA+GG | Overall | 3,414 | 0.87 (0.76, 1.00) | 1.97 | 0.05 | 0 | Fixed | |

| AA vs. GG | Overall | 1819 | 1.43 (0.62, 3.30) | 0.85 | 0.40 | 93 | Random | |

| A vs. G | Overall | 6,828 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.06 | 0.96 | 0 | Fixed | |

| Endometriosis | AA vs. AG+GG | Overall | 1,118 | 0.99 (0.75, 1.32) | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0 | Fixed |

| Asian | 769 | 0.92 (0.65, 1.32) | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0 | Fixed | ||

| AA+AG vs. GG | Overall | 1,118 | 1.73 (0.92, 3.25) | 1.71 | 0.09 | 75 | Random | |

| Asian | 769 | 1.66 (0.60, 4.62) | 0.97 | 0.33 | 82 | Random | ||

| AG vs. AA+GG | Overall | 1,410 | 1.24 (1.00, 1.53) | 1.97 | 0.05 | 10 | Fixed | |

| Asian | 1,061 | 1.17 (0.92, 1.49) | 1.29 | 0.20 | 24 | Fixed | ||

| AA vs. GG | Overall | 539 | 1.54 (0.79, 2.97) | 1.28 | 0.20 | 67 | Random | |

| Asian | 367 | 1.42 (0.50, 4.05) | 0.67 | 0.51 | 75 | Random | ||

| A vs. G | Overall | 2,236 | 1.23 (0.90, 1.68) | 1.31 | 0.19 | 64 | Random | |

| Asian | 1,538 | 1.22 (0.71, 2.09) | 0.73 | 0.47 | 76 | Random |

As for HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometriosis, 1410 participants including 646 cases and 764 controls were analyzed. The meta-analysis of the overall population failed to show any significant association between HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometriosis (AA vs. AG+GG: OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.75-1.32; AA+AG vs. GG: OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 0.92-3.25; AG vs. AA+ GG: OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.00-1.53; AA vs. GG: OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 0.79-2.97; A vs. G: OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.90-1.68). A subgroup analysis based on race stratification was also performed. For Asian people, mainly Taiwanese and Japanese, no significantly increased or decreased risks of endometriosis were found for HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms (AA vs. AG+GG: OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.65-1.32; AA+AG vs. GG: OR = 1.66, 95% CI = 0.60-4.62; AG vs. AA+ GG: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.92-1.49; AA vs. GG: OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.50-4.05; A vs. G: OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.71-2.09).

Only one case-control study on HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of uterine leiomyoma was available [28]. Even though the frequencies of rs605059 AA genotype and A allele were significantly increased in patients with uterine leiomyoma compared to healthy controls (GG vs. AA, OR 0.40, 95 % CI 0.20-0.82; G vs. A, OR 0.68, 95 % CI 0.50-0.94), we could still not conclude that the genotype of HSD17B1 rs605059 played a role in the leiomyoma tumorigenesis.

Publication bias

The shapes of the funnel plots appeared to be symmetrical in all comparison genetic models, suggesting the lack of publication bias for the comparisons and indicating the reliability of this meta-analysis.

Discussion

Estrogen has been reported to be one pivotal risk factor for the development of many uterine diseases like endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma. In recent years, polymorphisms of genes encoding key proteins in the pathway of estrogen synthesis and metabolism have been explored to identify possible genetic risk factors for uterine diseases [29,30]. One importantly involved protein is the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (HSD17B1), an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of estrone to the more biologically active estradiol in the final step of estrogen synthesis. Polymorphisms of HSD17B1 gene rs605059 have been investigated in some previous studies to explore their association with the risks of endometrial cancer, endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma. However, the results have been inconsistent, possibly due to limited sample sizes and variant participant characteristics. In order to address the inconsistencies of previously published studies, and to draw a more concrete conclusion, the current meta-analysis was performed.

In the present meta-analysis, 8 case-control studies were enrolled. 3 were about endometrial cancer, 4 were about endometriosis and 1 was about uterine leiomyoma. As for endometrial cancer, 3,414 participants including 1,441 cases and 1,973 controls were analyzed. No association was found between the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometrial cancer using 5 different genotype or allele comparisons. Among the 4 case-control studies of endometriosis, one study reported that A allele of HSD17B1 conferred higher risk for endometriosis and another study reported that HSD17B1 SNP A allele increased overall endometriosis risk, especially for stage I-II diseases [26,27]. In contrast, the other two studies failed to reveal any significant relationship between HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometriosis [24,25]. By performing a meta-analysis, we concluded that the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of endometriosis were not significantly associated. The pooled results of a subgroup analysis on Asian people were consistent with the overall meta-analysis. Since there was only one case-control study available to explore the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of uterine leiomyoma, we could hardly make any concrete conclusion even though it revealed that the frequencies of rs605059 AA genotype and A allele were significantly increased in patients with uterine leiomyoma compared to healthy controls.

Despite our efforts to pool the results of currently published case- control studies, some disadvantages of the present meta-analysis should not be ignored. Firstly, the number of available studies was very limited. 3 studies were found for endometrial cancer, 4 were for endometriosis and only 1 for uterine leiomyoma. It is possible that the results of unpublished studies or further investigations might be differed from the present conclusion, thus cautions should be paid to explain the results [31]. Secondly, this meta-analysis was based on unadjusted estimations. It is known that other risk factors like age and menopausal status were also important in the development of uterine diseases [32-35]. These confounding factors might affect the validity of the results. Thirdly, available studies regarding these associations in Asian ethnicities were not sufficient. The subgroup analysis included mainly Japanese and Taiwanese Chinese people. Even though evidence for relationship between the HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and endometriosis was found in Japanese population, the overall analysis showed no significant association. Thus, studies enrolling more Asians were required.

To our knowledge, the present study was the first meta-analysis exploring the association between HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risks of uterine diseases. Despite all the disadvantages mentioned above, we could still conclude that HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms were not associated with the risks of endometrial cancer and endometriosis. Further studies are needed to validate the conclusion and clarify the association between HSD17B1 rs605059 polymorphisms and the risk of uterine leiomyoma.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (No. 2014AA020708) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 20120181110029).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Zhu BT, Conney AH. Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1–27. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medikare V, Kandukuri LR, Ananthapur V, Deenadayal M, Nallari P. The genetic bases of uterine fibroids: a review. J Reprod Infertil. 2011;12:181–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon YT, Park IA, Kim YB, Kim JW, Park NH, Kang SB, Lee HP, Song YS. Steroid receptor expressions in endometrial cancer: clinical significance and epidemiological implication. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Y, Lin X, Zhou S, Xu N, Yi T, Zhao X. The associations between the polymorphisms of the ER-α gene and the risk of uterine leiomyoma (ULM) Tumour Biol. 2013;34:3077–82. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson BE, Feigelson HS. Hormonal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:427–433. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Normand T, Narod S, Labrie F, Simard J. Detection of polymorphisms in the estradiol 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase II gene at the EDH17B2 locus on 17q11-q21. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:479–83. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adlercreutz H, Mazur W. Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases. Ann Med. 1997;29:95–120. doi: 10.3109/07853899709113696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peltoketo H, Luu-The V, Simard J, Adamski J. 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD)/17-ketosteroid reductase (KSR) family; nomenclature and main characteristics of the 17HSD/KSR enzymes. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999;23:1–11. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0230001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luu-The V. Analysis and characteristics of multiple types of human 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;76:143–51. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miettinen M, Mustonen M, Poutanen M, Isomaa V, Wickman M, Söderqvist G, Vihko R, Vihko P. 17Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in normal human mammary epithelial cells and breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;57:175–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1006217400137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vihko P, Härkönen P, Soronen P, Törn S, Herrala A, Kurkela R, Pulkka A, Oduwole O, Isomaa V. 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases--their role in pathophysiology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feigelson HS, McKean-Cowdin R, Coetzee GA, Stram DO, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE. Building a multigenic model of breast cancer susceptibility: CYP17 and HSD17B1 are two important candidates. Cancer Res. 2001;61:785–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu AH, Seow A, Arakawa K, Van Den Berg D, Lee HP, Yu MC. HSD17B1 and CYP17 polymorphisms and breast cancer risk among Chinese women in Singapore. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:450–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karageorgi S, McGrath M, Lee IM, Buring J, Kraft P, De Vivo I. Polymorphisms in genes hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase-17b type 2 and type 4 and endometrial cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:54–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low YL, Li Y, Humphreys K, Thalamuthu A, Li Y, Darabi H, Wedrén S, Bonnard C, Czene K, Iles MM, Heikkinen T, Aittomäki K, Blomqvist C, Nevanlinna H, Hall P, Liu ET, Liu J. Multi-variant pathway association analysis reveals the importance of genetic determinants of estrogen metabolism in breast and endometrial cancer susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang HP, Gonzalez Bosquet J, Li Q, Platz EA, Brinton LA, Sherman ME, Lacey JV Jr, Gaudet MM, Burdette LA, Figueroa JD, Ciampa JG, Lissowska J, Peplonska B, Chanock SJ, Garcia-Closas M. Common genetic variation in the sex hormone metabolic pathway and endometrial cancer risk: pathway-based evaluation of candidate genes. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:827–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber A, Keck CC, Hefler LA, Schneeberger C, Huber JC, Bentz EK, Tempfer CB. Ten estrogen-related polymorphisms and endometriosis: a study of multiple gene-gene interactions. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1025–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185259.01648.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu X, Zhou Y, Feng Q, Wang R, Su L, Long J, Wei B. Association of endometriosis risk and genetic polymorphisms involving biosynthesis of sex steroids and their receptors: an updating meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson SH, Bandera EV, Orlow I. Variants in estrogen biosynthesis genes, sex steroid hormone levels, and endometrial cancer: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:235–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitawaki J, Kado N, Ishihara H, Koshiba H, Kitaoka Y, Honjo H. Endometriosis: the pathophysiology as an estrogen-dependent disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83:149–55. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashton KA, Proietto A, Otton G, Symonds I, McEvoy M, Attia J, Gilbert M, Hamann U, Scott RJ. Polymorphisms in genes of the steroid hormone biosynthesis and metabolism pathways and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34:328–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai Q, Xu WH, Long JR, Courtney R, Xiang YB, Cai Q, Cheng J, Zheng W, Shu XO. Interaction of soy and 17beta-HSD1 gene polymorphisms in the risk of endometrial cancer. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:161–7. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32801112a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setiawan VW, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, De Vivo I. HSD17B1 gene polymorphisms and risk of endometrial and breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:213–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu CH, Yang JG, Chang YJ, Hsu CC, Kuo PL. Screening of a panel of steroid-related genes showed polymorphisms of aromatase genes confer susceptibility to advanced stage endometriosis in the Taiwanese Han population. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang HS, Wu HM, Cheng BH, Yen CF, Chang PY, Chao A, Lee YS, Huang HD, Wang TH. Functional analyses of endometriosis-related polymorphisms in the estrogen synthesis and metabolism-related genes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuchiya M, Nakao H, Katoh T, Sasaki H, Hiroshima M, Tanaka T, Matsunaga T, Hanaoka T, Tsugane S, Ikenoue T. Association between endometriosis and genetic polymorphisms of the estradiol-synthesizing enzyme genes HSD17B1 and CYP19. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:974–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamp M, Peters M, Reinmaa E, Haller-Kikkatalo K, Kaart T, Kadastik U, Karro H, Metspalu A, Salumets A. Polymorphisms in ESR1, ESR2 and HSD17B1 genes are associated with fertility status in endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:425–33. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.495434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cong RJ, Huang ZY, Cong L, Ye Y, Wang Z, Zha L, Cao LP, Su XW, Yan J, Li YB. Polymorphisms in genes HSD17B1 and HSD17B2 and uterine leiomyoma risk in Chinese women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:701–5. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okishiro M, Taguchi T, Jin Kim S, Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6 10 and CYP2C19 2, 3 are not associated with prognosis, endometrial thickness, or bone mineral density in Japanese breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Cancer. 2009;115:952–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reich O, Regauer S, Tempfer C, Schneeberger C, Huber J. Polymorphism 1558 C > T in the aromatase gene (CYP19A1) in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32:626–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Y, Zhao X, Zhou C, Yang L, Liu Y, Bian C, Gou J, Lin X, Wang Z, Zhao X. The associations between the Val158Met in the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene and the risk of uterine leiomyoma (ULM) Gene. 2013;529:296–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas D, Wurm P, Schimetta W, Schabetsberger K, Shamiyeh A, Oppelt P, Binder H. Endometriosis patients in the postmenopausal period: pre- and postmenopausal factors influencing postmenopausal health. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:746705. doi: 10.1155/2014/746705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cote ML, Alhajj T, Ruterbusch JJ, Bernstein L, Brinton LA, Blot WJ, Chen C, Gass M, Gaussoin S, Henderson B, Lee E, Horn-Ross PL, Kolonel LN, Kaunitz A, Liang X, Nicholson WK, Park AB, Petruzella S, Rebbeck TR, Setiawan VW, Signorello LB, Simon MS, Weiss NS, Wentzensen N, Yang HP, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Olson SH. Risk factors for endometrial cancer in black and white women: a pooled analysis from the Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium (E2C2) Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:287–96. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Je Y, DeVivo I, Giovannucci E. Long-term alcohol intake and risk of endometrial cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study, 1980-2010. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:186–94. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiaffarino F, Bravi F, Cipriani S, Parazzini F, Ricci E, Viganò P, La Vecchia C. Coffee and caffeine intake and risk of endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:1573–9. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]