Abstract

There is growing evidence suggesting that cancer stem cells (CSCs) are playing critical roles in tumor progression, metastasis and drug resistance. However, the role of CSCs in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains elusive. In this study, we enriched for stem-like cells from tumor spheres derived from NSCLC cell line A549 cultured in serum-free medium. Our results showed that sphere-derived cells expressed various stem cell markers such as CD44, CD133, Sox2 and Oct4. Compared with the corresponding cells in monolayer cultures, sphere-derived cells showed marked morphologic changes and increased expression of the stem cell markers CD133. Furthermore, we found that sphere-derived cells exhibited increased proliferation, cell-cycle progression as well as drug-resistant properties as compared to A549 adherent cells. Consistently, expression of several drug resistance proteins, including lung resistance-related protein (LRP), glutathion-S-transferase-π (GST-π) and multidrug resistance proteins-1 (MRP1) were all significantly enhanced in sphere-derived cells. These results indicate the enrichment of CSCs in sphere cultures and support their role in regulating drug resistance in NSCLC.

Keywords: Cancer stem cell, multidrug resistance, CD133, MRP1, LRP, GST-π

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the world with 1.3 million deaths worldwide annually [1,2]. In spite of current developments in multidisciplinary treatment strategies and an expanding panel of chemotherapy agents, the chemoresistance of lung cancer remains a major unresolved clinical and scientific problem. Data from the researches reveals that chemoresistance to carboplatin and cisplatin was documented in 68% and 63% in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), respectively [3], and often recurs with a chemoresistance phenotype shortly in approximately 80% of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cases [4]. Although some patients have a good initial response, all lung cancers will eventually develop resistance to the chemotherapeutic agents to which they are exposed [5]. Taking into account the chemoresistance is a ringleader to the tumor relapse after chemotherapeutic therapy, refined investigation on the mechanisms of chemoresistance is urgently desired in lung cancer to improve survival rate.

Recently, increasing evidence indicates that cancer stem cells (CSCs) are initiators of the occurrence, development and recurrence of malignant tumors [6]. According to this CSCs model, CSCs have been hypothesized to be resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiation therapy and are thought to be the responsible for tumor survival and re-growth post chemotherapy [1]. In recent years, some drug resistance-related features have been studied by an increasing number of researchers in CSCs derived from a variety of tumor types, including glioma [7], leukemia [8,9], hepatocellular carcinoma [10], prostate [11], thyroid [12], colorectal and ovarian carcinoma [13,14]. According the reports, the mechanisms responsible for the multidrug resistance in these CSCs was involved in increasing efflux of drug, enhancing repair/increasing tolerance to DNA damage, high antiapoptotic potential, decreasing permeability and enzymatic deactivation. In addition, some molecular characterizations associated with drug resistance, such as over expression ABCA2 and ABCG2 of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, and heat shock proteins (Hsps), were also revealed in side population or stem-like cells derived from lung cancer by researchers over the few years [15-17]. However, Apart from these important results, the actual mechanisms underlying the chemoresistance of lung cancer stem or initiation cells are not fully understood thus far. Due to the central role performed by CSCs in the recurrence of cancer after chemotherapy, Understanding the mechanisms of drug resistance in this lung cancer subpopulation may improve the results of treatment.

In this study, after the isolation and identification of clusters of lung stem-like cells growing as floating tumorospheres from the A549 lung cancer cell line, some of these features, such as the capability of cell proliferation and resist apoptosis, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) study to first-line chemotherapy agents (cisplatin, DDP; and gemcitabine, GEM), the Cell Cycle and the expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1) mRNA, Lung resistance-related protein (LRP) mRNA and glutathion-S-transferase-π (GST-π) protein were examined. Our results indicate that, comparing to A549 lung cancer cell line, lung cancer stem cells (LCSCs) have more capability of anti-apoptotic and drug resistance. Selective targeting of LCSCs could help to improve the development of novel therapeutics for lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Cells lines and tumorsphere culture

A549 human lung carcinoma cells (ATCC) were grown in Dulbecco’s modification of eagle’s medium (DMEM, Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA), in a 37°C humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To generate suspended and stem-like sphere growing cells, adherent cells were dissociated into a single-cell and seeded in 6-well plates at 1 × 103 cells/well with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal FBS for 2 weeks. Thereafter, holoclones [18] (50-200 cells) were isolated using cloning cylinders (Corning, USA) and cultured with serum-free stem cell medium containing DMEM/F12 (Gibco), B27 (1×, Gibco), recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF, 20 ng/ml; Sigma, USA), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, 20 ng/ml; Upstate, USA), and insulin (4 U/l; Sigma) for another 2-3 weeks. The medium is referred to as ‘Cancer Stem Cell medium’ (CSM). After primary tumor spheres reached approximately 100-200 cells/sphere, the spheres were dissociated and single cells were cultured for another 1-2 weeks with CSM until form secondary spheres. The secondary spheres were collected before initiating the characterization experiments.

Detection of the CD133 expression

Cells of A549 cell line and A549 spheres expressing CD133 antigen were identified by direct immunofluorescent staining using CD133/1 (AC133) antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, Germany) directly conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE). Cells were trypsinized by 0.25% trypsin and rinsed in 0.01% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS pH 7.4), at least 500,000 cells were first treated with FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and then incubated in the dark at 4°C for 10 minutes with CD133/1 fluorescent-labelled monoclonal antibody. After washing steps, the expression of CD133 was evaluated by flow cytometry (Beckman, USA).

Cell proliferation analysis

Cells dissociated from the A549 cell line, A549 secondary spheres were prepared into single cell suspension and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4000/ml, 200 μl/well, 37°C, incubation for 1-7 days. 10 μl MTT (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) was added, The cells were incubated for 4 h and then each well by adding 100 μl formanzan lysate (Beyotime). After the plates were incubated for 4 h, the optical density of the solution in the wells was measured at 570 nm in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent monitor (U-Quat, USA). Each with three-wells, the cell growth curve was drew by average value. At the same time established a well of only medium without cells as blank control. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Viability study

Cells dissociated from the A549 cell line and A549 secondary spheres were injected to a 96-well plate at a cell density of 1 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight. On the next day, old medium was removed and fresh medium supplemented with various concentrations (1.5-24 μg/ml) of DDP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and (80-400 μg/ml) of GEM (Sigma,). Control cells received fresh medium without anticancer drugs. Three wells were prepared for each group. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, Cell viability was determined by the MTT cell viability/cytotoxicity assay kit (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was then measured with an Enzyme-linked immunosorbent (U-Quat) at 570 nm. The IC50 value, defined as the drug concentration required to reduce cell survival to 50% as determined by the relative absorbance of MTT, was assessed by probit regression analysis using SPSS11.5 statistical software.

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

Cells dissociated from the A549 cell line, A549 secondary spheres were injected into 6-well plates at the cell density of 106 cells/well cultured in serum-free DMEM. The cells were treated with IC50 concentrations of chemotherapeutic drugs (DDP and GEM) for 48 h. Then, cells were collected for cell cycle and apoptosis analyses. Control A549 cell line and control A549 spheres were not treatment by drugs.

For cell cycle analyses, the collected cells fixed in 75% cold ethanol for 1 day at -20°C. Later, the cells were washed in cold PBS and incubated with PI (50 μg/ml) containing RNase at 37°C for 30 min in darkness. Cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman, USA).

For apoptosis analyses, the collected cells were washed with the collected culture medium, and suspended in PBS. Then, the cells were incubated with the Human Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Kit (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer’s instructions before analysis by flow cytometry (Beckman) analysis.

Western-blot analysis

Protein extracts of A549 cells line, A549 secondary spheres and HBE were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred on PVDF (Millipore, USA) membranes using ECL Semi-dry Blotters (TE70PWR, USA) electro transfer system. After blocking, the PVDF membranes were washed three times with TBST at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies for GST-π (1:1500, Booster, China), MRP1 (1:1000, Abcam, UK) and LRP (1:1000, Abcam, UK) at 4°C overnight. After extensive washing, membranes were incubated with secondary peroxidase-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz, USA) for 1 h. After washing four times for 15 min with TBST at room temperature once more, the bands were detected by a Chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL) (Beyotime Biotech, Jiangsu, China). The films were scanned and quantitation was carried out with Optiquant software (GBOX/CHEM, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was used for detecting the expression of some stem cell-related markers in tumor spheres, GST-π in tumor spheres and A549 cells. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 15 min and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and incubated with 3% BSA for 30 min at room temperature to block nonspecific binding. Then, cells were incubated with primary antibodies against, CD133 (mouse monoclonal IgG1, Abcam, Great Britain), stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1, goat polyclonal, R&D, USA), CD44s (mouse monoclonal IgG1, Neo Markers, USA), Oct4 (mouse monoclonal IgG1, Abcam), Nanog (mouse monoclonal IgG1, Abcam), Sox2 (sex determining region Y-box 2, Novus Biologicals, USA), GST-π (1:200, Boster). The appropriate secondary antibodies (TRITC red goat anti-rabbit, Cy3 red donkey anti-goat and Cy3 red rabbit anti- mouse; Molecular Probes, USA) were used. The cells were counterstained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma) to visualize cell nuclei and examined under a LCM (Leica, Germany). The mean fluorescence intensity of GST-π in cells was measured using the Leica Confocal Software (Image-Pro Plus 10.0).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times and representative results are presented. Where applicable, quantitative data were presented as means ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Tumor sphere formation and growth curves were analyzed by ANOVA with a SPSS11.5 statistical software.

Results

Generation of A549 tumor spheres from A549 cell line

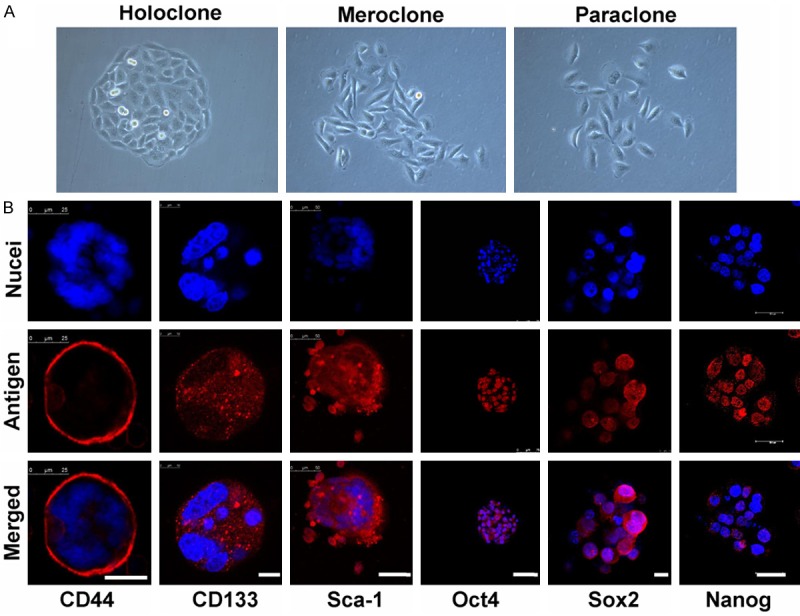

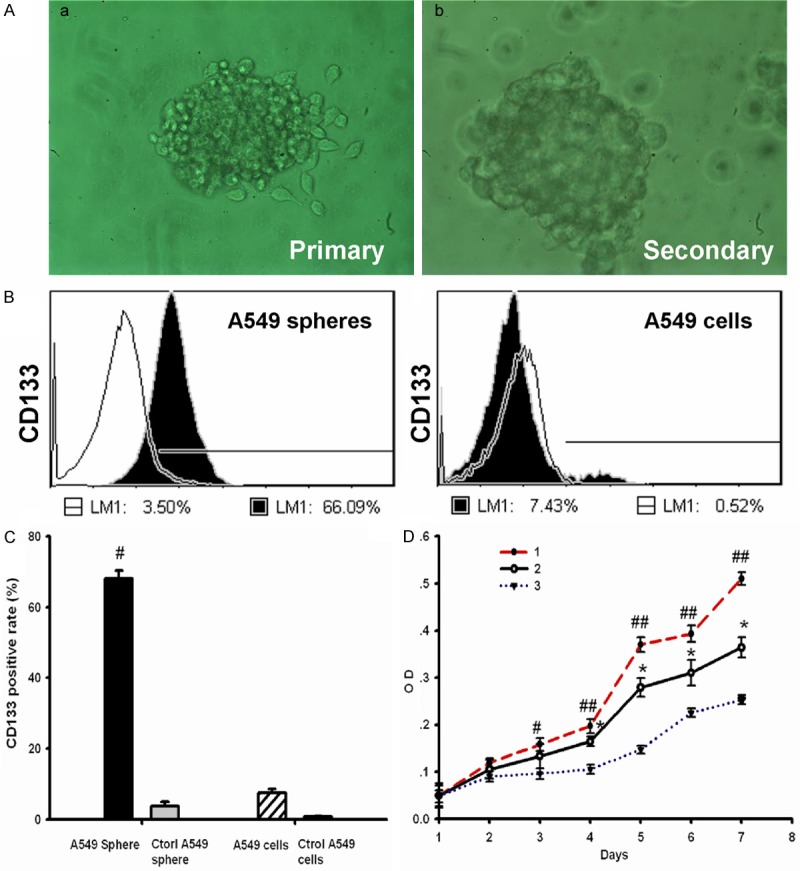

A549 cells formed three morphologically different colonies (Figure 1A): holoclone, meroclone and paraclone by using single-cell cloning culture. Then, the holoclones were dissociated and directly incubation with CSM. Cells started to lose their characteristic epithelial morphology within 48-72 hours. Some adherent cells typically lost a rhomboidal epithelial shape and became floating cells or cell clusters. The small spheres/well each containing 5-10 cells were observed after 5-6 days. In 2 weeks, the diameter of these Primary spheres increased by 10- to 30-fold (Figure 2A). Many adherent non-sphere forming cells could be seen in the bottom of the wells. Single cell suspension prepared from primary tumor spheres was examined for the capacity to form secondary spheres by single parental cells in fresh CSM. The result shows that secondary spheres (Figure 2A) were formed in the 75-ml flask seeded with cells from Primary tumor spheres. The tumor spheres could be passaged every 2-3 weeks for many generations in fresh CSM.

Figure 1.

Isolation and identification of LCSCs. A. Three types of colonies formed by A549 cells. (400×). B. Immunostaining of stem cell markers in secondary spheres. Nuclei were stained using DAPI (blue). LCM, scale bar = 25 10, 50, 75, 10, 30 μm (left to right).

Figure 2.

A549 cancer spheres have high express CD133 and more self renewal capability. A. The morphology of tumor spheres. a. Primary tumor spheres formed in the CSM medium. b. Secondary spheres derived from single parental cells of primary tumor spheres under microscopy. a and b. 200×. B. Flow cytometry analysis of CD133 in A549 cancer spheres (left) and A549 cells lines (right). Cells were labeled with fluorescent anti-CD133 antibody, which are shown as black areas. The white area on each box represents the corresponding negative control labeling, and the line denotes a positive gate. Numbers are the percentage of positive cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. C. Detection of CD133 positive rate among four groups cells. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of three experiments (n = 3). #P<0.05, compared to A549 cells. D. Growth curves 1. A549 cancer spheres cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS; 2. A549 cancer spheres cultured in serum-free Cancer Stem Cell medium; 3. A549 cells line cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. *P < 0.05, compared to Tumor stem cells in serum-free stem cell culture medium. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, compared to A549 cells line cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS.

Expression of stem cell-related markers marker in A549 tumor spheres

In order to investigate the expression of CD133 (one of the widely accepted CSCs marker) in A549 cancer sphere-growing cells, the single cell suspensions of A549 cells and A549 tumor spheres were analyzed by flow cytometry. Our results showed that the fractions of CD133+ expressing cells in A549 tumor spheres was significantly high than A549 cells line (Figure 2B and 2C, sphere, 66 ± 1.23%; sphere control, 3.5 ± 1.12%; cell line, 10.2 ± 0.83%; cell line control, 1.79 ± 0.56%; n = 3, P < 0.05). These results indicate a good enrichment of CD133+ subpopulations in the A549 tumor spheres. In addition, fluorescent immunostaining revealed that some stem cell-related markers, such as CD133, Sca-1 (A normal bronchioalveolar stem cell or LCSCs marker), CD44s (A stem cell marker of some epithelium-derived tumors, such as breast CSCs), Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog [Embryonic stem cell (ES)/induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) or CSCs markers] were positive in these secondary tumor spheres (Figure 1B).

Proliferation capability of A549 tumor spheres cells

To evaluate A549 tumor spheres proliferation capability, We examined the growth of A549 tumor spheres cells and A549 cells line by the MTT assay. Optical density of dissociated A549 tumor spheres in DMEM with 10% FBS was significantly increased than A549 cells line in DMEM with 10% FBS on 3 days (Figure 2D, sphere, 0.16 ± 0.01, cells line, 0.09 ± 0.01; n = 3, P < 0.05). Meanwhile, Optical density of dissociated A549 tumor spheres in CSM was also significantly increased than A549 cells line in DMEM with 10% FBS on 4 days (Figure 1D, sphere, 0.20 ± 0.02; cells line, 0.11 ± 0.01; n = 3, P < 0.05). The doubling time of A549 tumor spheres cells in DMEM with 10% FBS was 46.71h compared to 53.96 h in CSM. However, A549 cells line more quiescent in DMEM with 10% FBS, These cells proliferated with a doubling time of 75.6 h (Figure 2D).

A549 tumor spheres express more drug resistant capability

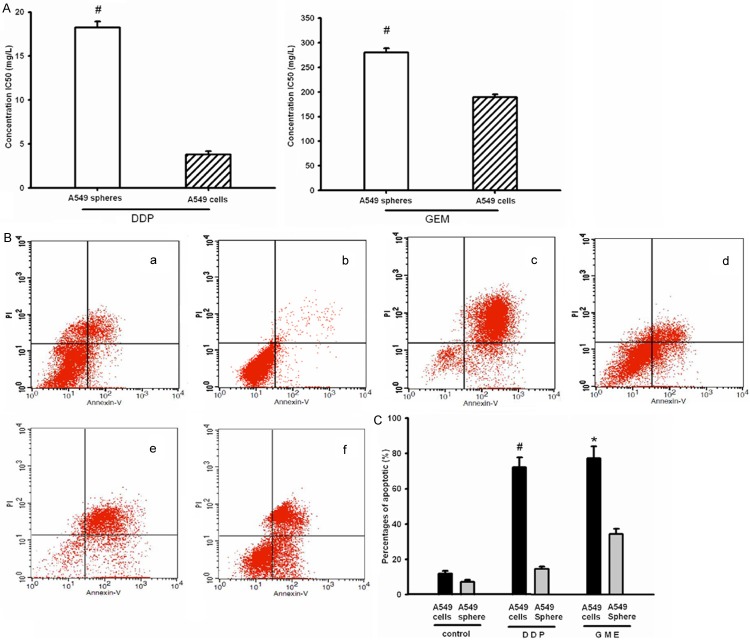

Viability study revealed that the growth and inhibition of DDP or GEM to A549 cells line and A549 tumor spheres cells. The results of IC50 shown that A549 tumor spheres cells have significantly high drug resistant than A549 cells line (Figure 3A). DDP inhibited the growth of A549 tumor spheres cells and A549 cells line with an IC50 of 18.25 ± 0.66 mg/L and 3.8 ± 0.36 mg/L respectively. GEM inhibited the growth of A549 tumor spheres cells and A549 cells line with an IC50 of 280.38 ± 8.2 mg/L and 189.47 ± 5.65 mg/L respectively. Meanwhile, under the pressure of DDP or GEM, The apoptotic percentages of A549 tumor spheres cells and A549 cells line had increase compared with controls, and A549 cells line was more significant increasing the apoptotic percentages than A549 tumor spheres in DDP or GEM (Figure 3B and 3C, sphere control, 7.16 ± 1.12%; cell line control, 11.83 ± 1.56%; sphere/DDP, 14.64 ± 1.23%; cell line/DDP, 72.16 ± 5.63%; sphere/GEM, 34.38 ± 2.94%; cell line/DDP, 77.32 ± 6.73%; n = 3, P < 0.05). It also suggested that A549 tumor spheres cells have stronger drug resistant than A549 cells line.

Figure 3.

Measurement of the sensitivity of A549 cancer spheres and A549 cells line to anticancer drugs (DDP and GEM). A. The lethal doses (IC50) of DDP (left) and GEM (right) in A549 cancer spheres and A549 cells line, The data shown represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments(n = 3). #P<0.05, compared to A549 cells line. B. Graphs shows flow cytometry of the apoptotic induced by DDP and GEM. The cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodideed. a. A549 cells line; b. A549 cancer spheres; c. A549 cells line/DDP; d. A549 cancer spheres/DDP; e. A549 cells line/GEM; f. A549 cancer spheres/GEM. C. Histograms represent the percents of Apoptotic of DDP and GEM in A549 cancer spheres and A549 cells line. The data shown represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3), #P < 0.05, compared with A549 spheres/DDP; ★P < 0.05, compared with A549 spheres/GME.

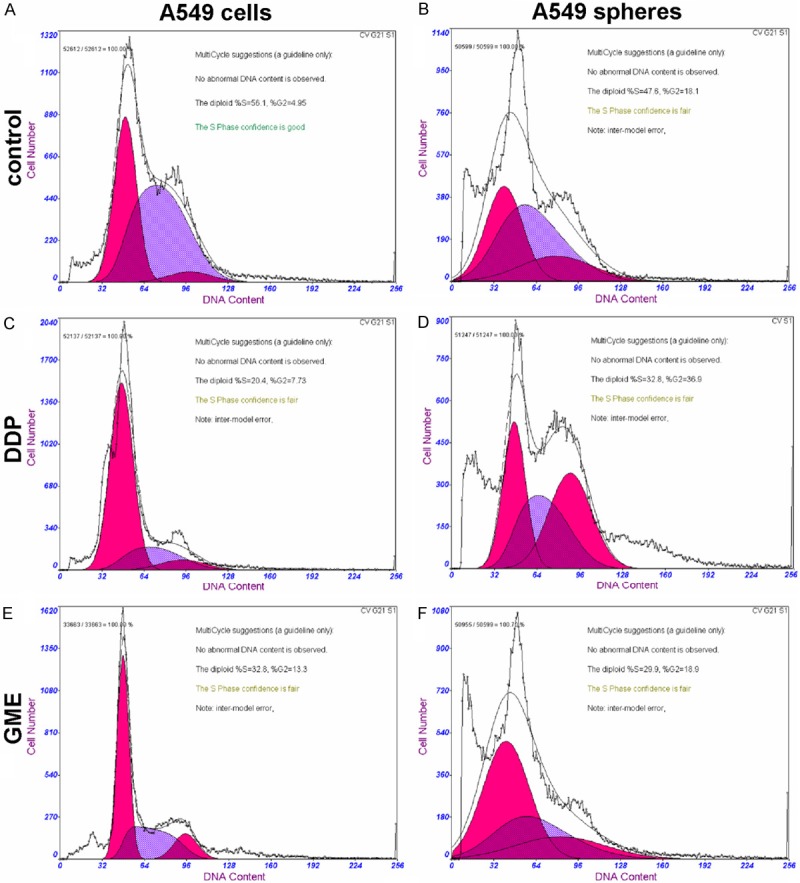

Cell cycle distribution of A549 cells line and A549 tumor spheres on effects of chemotherapeutic drugs

Due to previous studies on the cell cycle distribution of cultured stem cells reported diverse results. We investigated whether the cell cycle distribution was related to “stemness” or “drug resistant” of cells. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 4, cell cycle analysis revealed that the number of A549 spheres cells in the G0/G1 phase and S phase similar to A549 cells line cells. However, an increase in the number of A549 spheres cells in the G2/M phase was apparent. Both DDP and GME can block cells from G1 to S phase of the progress and initiate apoptosis. When treated with the two kinds of chemotherapy drugs for 48 h, both the treated A549 cells line (A549 cell line/DDP and A549 cell line/GME) at the S phase significantly decreased as compared to control group, accompanied by an increase in the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase. Nevertheless, With regard to the A549 spheres, the DDP and GME treated groups (A549 spheres/DDP and A549 spheres/GME) had no significant changes in the G0/G1 phase and S phase were seen as compared to the control group. In addition, the percentages of G2/M phase significant increasing in A549 spheres/DDP group and a little accumulation in spheres/GME group compared their control group.

Table 1.

Cell cycle distribution of A549 cells line and A549 tumor spheres cells in each groups (%)

| Cell | G0/G1 | S | G2/M |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control A549 cell line | 38.4 ± 1.28 | 52.1 ± 2.36 | 4.75 ± 0.35 |

| Control A549 spheres | 36.5 ± 1.46 | 45.8 ± 1.87 | 17.2 ± 0.54a |

| A549 cell line/DDP | 70.61 ± 2.32 | 18.25 ± 1.03b | 5.94 ± 0.31 |

| A549 spheres/DDP | 31.43 ± 1.15 | 31.75 ± 2.05 | 35.82 ± 1.95c |

| A549 cell line/GEM | 63.71 ± 2.55 | 28.94 ± 1.54b | 12.52 ± 0.27 |

| A549 spheres/GEM | 48.29 ± 1.74 | 30.52 ± 1.95 | 20.46 ± 1.31 |

P < 0.05, comparing with control A549 cell line with significant high proportion in the G2/M phase;

P < 0.05, comparing with control A549 cell line with significant decrease in S phase;

P < 0.05, comparing with control A549 spheres with significant increase in G2/M phase.

Figure 4.

Effect of the IC50 concentration of Cisplatin (DDP) and Gemcitabine (GEM) on the cell cycle profile of A549 cells line and A549 spheres. A. A549 cells line; B. A549 cells line/DDP; C. A549 cells line/GEM; D. A549 cancer spheres; E. A549 cancer spheres/DDP; F. A549 cancer spheres/GEM. This experiment was repeated three separate times, and similar results were obtained. The representative flow cytometry pattern is shown.

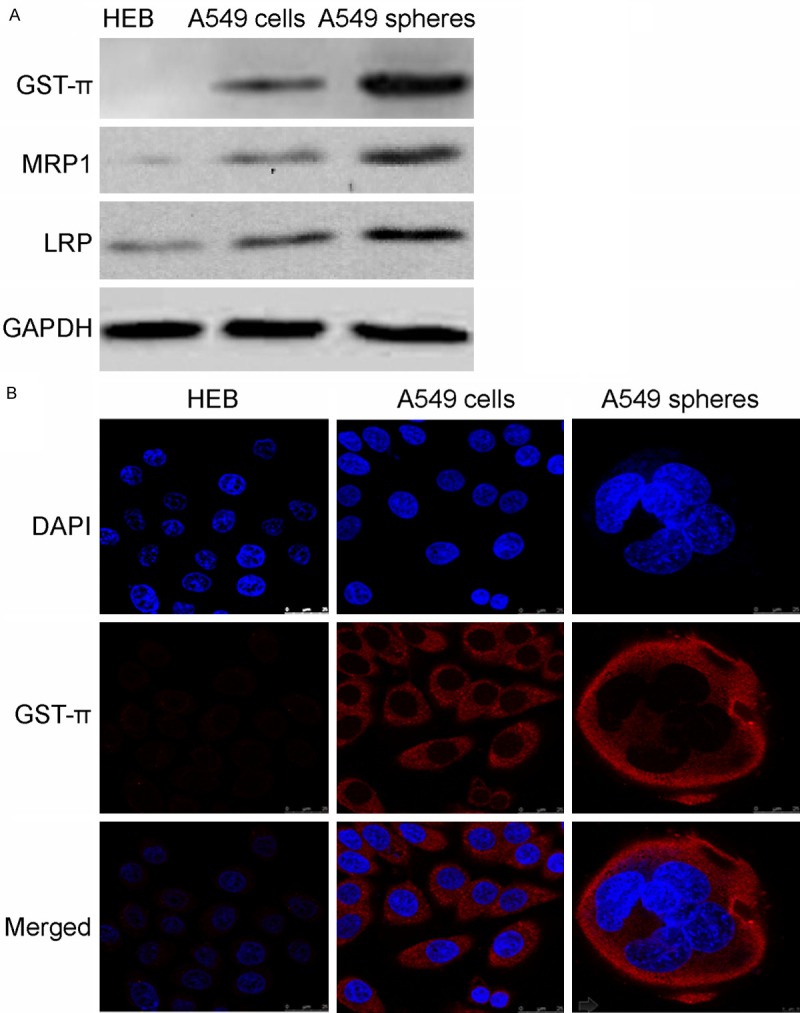

Upregulation of drug resistant proteins GST-π, MRP1 and LRP in A549 tumor spheres

One possible mechanism for chemoresistance in A549 tumor spheres is enhanced expression of drug resistant proteins. To test this possibility, we use western-blot to examine expression of several drug resistant proteins, including GST-π, MRP1 and LRP, in HEB, A549 cells and A549 tumor spheres. As expected, expression of all three proteins was enhanced in A549 tumor spheres with the most dramatic change occur for GST-π (Figure 5A). We further validated this result using Immunofluorescence staining of GST-π in these cells. As shown in Figure 5C, in line with western-blot, robust expression of GST-π expression is observed in A549 cells and tumor spheres but not HEB cells. Moreover, GST-π expression is significantly enhanced in A549 tumor spheres shown higher than that of A549 cells line (average signal intensity: sphere, 35.4 ± 2.32; cell line, 27.76 ± 2.24; n = 20, P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Enhanced expression of GST-π, MRP1 and LRP in A549 spheres. A. Western-blot of GST-π, MRP1 and LRP in HEB, A549 cells and A549 spheres. B. Immunofluorescence of GST-π expression in HEB, A549 cells and A549 spheres using confocal microscopy. Scale bars: 25 µm.

Discussion

CSCs are thought to play multiple roles in tumorigenesis. Previous studies selected CSCs, which can grow as spheres in the serum-free medium, from many human lung cancer cell lines and tumors by magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) methods depend on some stem cell markers [15,16,19-22]. As some studies have demonstrated that cell lines derived from prostate carcinoma and glioma can form morphologically heterogeneous colonies in vitro, due to the intrinsic stem cell hierarchies of their parental cells. The holoclones consist of CSCs, while the meroclone and paraclone show non-CSCs properties [18,23-26]. Therefore, in this current study, we chose A549 holoclones cells cultured with serum-free medium in the presence of EGF and FGF2 for obtaining tumor spheres. Some LCSC markers (such as CD133, Sca-1 and CD34), many embryonic stem (ES)- and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) - related core transcription factors (such as Sox2, Oct4 and Nanog) are overexpressed in these small subset of stem cell-like cells.

More interestingly, it has previously been shown that the expression of these markers and factors is not only related to the stemness but also to drug resistance. For example, CD133 currently serves as a useful marker for the isolation of CSCs in various tumors, including lung cancer [16,27-29]. In this study, our results show that A549 spheres considerably higher expression of CD133 than A549 cell line. It consistent with the previous reports that CD133+ fractions varied from 1.4% in A549 cells, whereas 31.7% in A549-derived tumor spheres and nearly 100% positive in H82 (Small-cell lung cancer lines) side population cells [19,30]. Moreover, this molecule also performs an important role in sustaining the resistance to chemo- or radiotherapy of CSCs in various tumors [31-33], such as NSCLC and glioma cells. Possible mechanisms may involve unregulated expressing of multiple drug resistance transporters, detoxifying enzymes, activated DNA repair machinery and resistance to apoptosis. Additionally, while Nanog, Sox2 and Oct4 are key transcription factors in maintaining ES cell pluripotency, they also influence CSCs’ resistance property. Knock down of Sox2 in glioma stem-like cells resulted in loss of the activation of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters [34-36]. These resistance characteristics inhibitions are also accompanied by the downregulation of Oct4 and Nanog in LCSCs and prostate cancer stem cell [37-39]. In addition, there is some evidence to indicate that other factors, such as CD44s and Sca-1, can also influence radiation resistance [40,41]. Thus, it is possible that LCSCs, which commonly overexpress either the surface markers or transcriptional factors mentioned previously, may also possess some resistance phenotype. In this study, the results suggest that A549 spheres cells are exhibited more extensive proliferative potential and significantly resistant to the two tested chemotherapeutic agents. It was high IC50 and low apoptosis rat of A549 spheres cells to DDP or GEM than A549 cells, which is coincidence with the literatures [14,16].

It is well known that cellular sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents relies on cell cycle kinetics that allows lethal cellular damage in highly proliferating cells [42]. In the process, chemotherapeutic agents generally cause DNA damage and interfere cell cycle resulting in apoptosis, such as DDP crosslinks DNA interfering with cell division by mitosis [43] and GEM major anti-DNA synthesis phase [44]. It remains undefined how the cell cycle changed in CSCs when chemotherapeutic intervention, elucidation of DNA damage response in isolated CSCs would enable targeting DNA damage checkpoint response in CSCs [45]. Intriguingly, we found the proportion of cells in the G2 phase of A549 spheres cells was both significantly higher than the A549 cells at before and after treatment with DDP or GEM. This data in line with recently findings that normal and malignant stem-like cells have an extended G2 cell cycle phase, the phase of the cell cycle associated with DNA repair, which is associated with apoptotic resistance. Targeting G2 checkpoint proteins releases these cells from the G2-block and makes them more prone to apoptosis [46]. This novel finding suggests that G2 phase contribute to drug resistance of A549 spheres and might be an attractive target for CSCs therapy.

Proposed mechanisms of multidrug resistance (MDR) in CSCs include enhanced expression of multidrug resistance transporters, anti-apoptotic factors, or increased levels of DNA damage repair proteins [47,48]. In our research, there are illustrated a significant increase in MRP1 (ABCC1), LPR and GST-π expression in A549 spheres cells. MRP1 belongs to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins, involved in export pumps that hamper the accumulation of anionic conjugates and oxidized glutathione in cytoplasm, and therefore play a critical role in reduces the formation of platinum-DNA adducts, detoxification and development of platinum-based drug resistance [49]. A series of studies has reported that MRP1 up-regulation in CD133 positive glioblastoma stem-like cells and SP lung cancer cells [15,48,49]. Likewise, LPR, another important MDR-associated protein, vaults act by effuxing drugs from the nucleus and/or the sequestration of drugs into exocytotic vesicles [50,51]. Recently study demonstrate that it can high expression of those genes in leukemic stem cell [52], but not involve in A549 CSCs so far. In addition, GST-π, the cytosolic detoxifcation protein, is generally accepted that the MRP1 is act in synergy with GST-π to confer resistance to the chemotherapeutic agents, especially platinum drugs [53-55]. Expression of GST-π varies between different CSCs, being high in human fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells [56], but low in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and prostate CSCs [57,58]. In A549 spheres, we presumed the overexpression of a GST-π in concert with MRP1 and/or LRP would give optimal resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. The available evidence, presented above, suggests that stem-like cell populations in A549 spheres could play an important role in drug resistance, possibly through activation of cell membrane drug effux transporters, and altered expression of detoxifying enzymes. Moreover, the concomitance increase of the genes and protein, MRP1, LPR and GST-π, suggested that lung CSCs was not the solo factor to maintain resist apoptosis and to pump the anti-tumor drugs out of cells.

In conclusion, the present work suggests that 549 spheres, which derived from 549 cells line directly, has enriched cancer stem-like cells and elevated capability of proliferation, anti-apoptotic and drug resistance than 549 cells. In addition, the combined working of MRP1, LPR and GST-π might responsible for the fact that lung CSCs may be spared by traditional chemotherapy and be rapidly recurrence. These observations have potentially important implications for future therapeutic approaches that target the lung CSCs and correlated drug resistance mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 81160027) and Natural Science Foundation of Jiang Xi Province (Grant numbers: 20114BAB205001).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Eramo A, Haas T, Maria RD. Lung cancer stem cells: tools and targets to fi ght lung cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4625–4635. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro SG, Tanner NT, Silvestri GA, Janes SM, Lim E, Vansteenkiste JF, Pirker R. Lung cancer: progress in diagnosis, staging and therapy. Respirology. 2010;15:44–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.d’Amato TA, Landreneau RJ, McKenna RJ, Santos RS, Parker RJ. Prevalence of in vitro extreme chemotherapy resistance in resected nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.037. discussion 446-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohmo S, Kijima T, Otani Y, Mori M, Minami T, Takahashi R, Nagatomo I, Takeda Y, Kida H, Goya S, Yoshida M, Kumagai T, Tachibana I, Yokota S, Kawase I. Cell surface tetraspanin CD9 mediates chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8025–8035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang A. Chemotherapy, chemoresistance and the changing treatment landscape for NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmaggi A, Boiardi A, Gelati M, Russo A, Calatozzolo C, Ciusani E, Sciacca FL, Ottolina A, Parati EA, La Porta C, Alessandri G, Marras C, Croci D, De Rossi M. Glioblastoma-derived tumorospheres identify a population of tumor stem-like cells with angiogenic potential and enhanced multidrug resistance phenotype. Glia. 2006;54:850–860. doi: 10.1002/glia.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs D, Daniel V, Sadeghi M, Opelz G, Naujokat C. Salinomycin overcomes ABC transporter-mediated multidrug and apoptosis resistance in human leukemia stem cell-like KG-1a cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:1098–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Wu R, Zhao L, Wu M, Yang L, Zou H. P-glycoprotein antibody functionalized carbon nanotube overcomes the multidrug resistance of human leukemia cells. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1399–1408. doi: 10.1021/nn9011225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu XL, Xing BC, Han HB, Zhao W, Hu MH, Xu ZL, Li JY, Xie Y, Gu J, Wang Y, Zhang ZQ. The properties of tumor-initiating cells from a hepatocellular carcinoma patient’s primary and recurrent tumor. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:167–174. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu T, Xu F, Du X, Lai D, Zhao Y, Huang Q, Jiang L, Huang W, Cheng W, Liu Z. Establishment and characterization of multi-drug resistant, prostate carcinoma-initiating stem-like cells from human prostate cancer cell lines 22RV1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;340:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng X, Cui D, Xu S, Brabant G, Derwahl M. Doxorubicin fails to eradicate cancer stem cells derived from anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells: characterization of resistant cells. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:307–315. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saigusa S, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Yokoe T, Okugawa Y, Kawamoto A, Yasuda H, Morimoto Y, Fujikawa H, Inoue Y, Miki C, Kusunoki M. Immunohistochemical features of CD133 expression: association with resistance to chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:345–350. doi: 10.3892/or_00000865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu L, McArthur C, Jaffe RB. Ovarian cancer stem-like side-population cells are tumourigenic and chemoresistant. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1276–1283. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho MM, Ng AV, Lam S, Hung JY. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem-like cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4827–4833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertolini G, Roz L, Perego P, Tortoreto M, Fontanella E, Gatti L, Pratesi G, Fabbri A, Andriani F, Tinelli S, Roz E, Caserini R, Lo Vullo S, Camerini T, Mariani L, Delia D, Calabro E, Pastorino U, Sozzi G. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905653106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu HS, Lin JH, Huang WC, Hsu TW, Su K, Chiou SH, Tsai YT, Hung SC. Chemoresistance of lung cancer stemlike cells depends on activation of Hsp27. Cancer. 2011;117:1516–1528. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locke M, Heywood M, Fawell S, Mackenzie IC. Retention of intrinsic stem cell hierarchies in carcinoma-derived cell lines. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8944–8950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salcido CD, Larochelle A, Taylor BJ, Dunbar CE, Varticovski L. Molecular characterisation of side population cells with cancer stem cell-like characteristics in small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1636–1644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei H, Zhai B, Yin S, Gygi S, Reed R. Evidence that a consensus element found in naturally intronless mRNAs promotes mRNA export. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2517–2525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, Yin S, Zhang Z, Xin D, Hu L, Kong X, Hurst LD. Evidence for common short natural trans sense-antisense pairing between transcripts from protein coding genes. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R169. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin S, Yang J, Lin B, Deng W, Zhang Y, Yi X, Shi Y, Tao Y, Cai J, Wu CI, Zhao G, Hurst LD, Zhang J, Hu L, Kong X. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of MLL2 in non-small cell lung carcinoma from Chinese patients. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6036. doi: 10.1038/srep06036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Claypool K, Tang DG. PC3 human prostate carcinoma cell holoclones contain self-renewing tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1820–1825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou ZH, Ping YF, Yu SC, Yi L, Yao XH, Chen JH, Cui YH, Bian XW. A novel approach to the identifi cation and enrichment of cancer stem cells from a cultured human glioma cell line. Cancer Lett. 2009;281:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin S, Deng W, Hu L, Kong X. The impact of nucleosome positioning on the organization of replication origins in eukaryotes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin S, Deng W, Zheng H, Zhang Z, Hu L, Kong X. Evidence that the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway participates in X chromosome dosage compensation in mammals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu SC, Ping YF, Yi L, Zhou ZH, Chen JH, Yao XH, Gao L, Wang JM, Bian XW. Isolation and characterization of cancer stem cells from a human glioblastoma cell line U87. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miki J, Furusato B, Li HZ, Gu YP, Takahashi H, Egawa S, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG, Srivastava S, Rhim JS. Identification of putative stem cell markers, CD133 and CXCR4, in hTERT-immortalized primary nonmalignant and malignant tumor-derived human prostate epithelial cell lines and in prostate cancer specimens. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3153–3161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin S, Wang P, Deng W, Zheng H, Hu L, Hurst LD, Kong X. Dosage compensation on the active X chromosome minimizes transcriptional noise of X-linked genes in mammals. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R74. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-7-r74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levina V, Marrangoni A, Wang TT, Parikh S, Su YY, Herberman R, Lokshin A, Gorelik E. Elimination of Human Lung Cancer Stem Cells through Targeting of the Stem Cell Factor-c-kit Autocrine Signaling Loop. Cancer Res. 2010;70:338–346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angelastro JM, Lame MW. Overexpression of CD133 promotes drug resistance in C6 glioma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1105–1115. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salnikov AV, Gladkich J, Moldenhauer G, Volm M, Mattern J, Herr I. CD133 is indicative for a resistance phenotype but does not represent a prognostic marker for survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:950–958. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shervington A, Lu C. Expression of multidrug resistance genes in normal and cancer stem cells. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:535–542. doi: 10.1080/07357900801904140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon HM, Sohn YW, Oh SY, Kim SH, Beck S, Kim S, Kim H. ID4 imparts chemoresistance and cancer stemness to glioma cells by derepressing miR-9*-mediated suppression of Sox2. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3410–3421. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jia X, Li X, Xu Y, Zhang S, Mou W, Liu Y, Lv D, Liu CH, Tan X, Xiang R, Li N. Sox2 promotes tumorigenesis and increases the anti-apoptotic property of human prostate cancer cell. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:230–238. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng WJ, Nie S, Dai J, Wu JR, Zeng R. Proteome, phosphoproteome, and hydroxyproteome of liver mitochondria in diabetic rats at early pathogenic stages. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:100–116. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900020-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen YC, Hsu HS, Chen YW, Tsai TH, How CK, Wang CY, Hung SC, Chang YL, Tsai ML, Lee YY, Ku HH, Chiou SH. Oct-4 expression maintained cancer stem-like properties in lung cancer-derived CD133-positive cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeter CR, Liu B, Liu X, Chen X, Liu C, Calhoun-Davis T, Repass J, Zaehres H, Shen JJ, Tang DG. NANOG promotes cancer stem cell characteristics and prostate cancer resistance to androgen deprivation. Oncogene. 2011;30:3833–3845. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan CT, Pang YL, Deng W, Babu IR, Dyavaiah M, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nat Commun. 2012;3:937. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin H, Glass J. The phenotypic radiation resistance of CD44+/CD24(-or low) breast cancer cells is mediated through the enhanced activation of ATM signaling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen MS, Woodward WA, Behbod F, Peddibhotla S, Alfaro MP, Buchholz TA, Rosen JM. Wnt/beta-catenin mediates radiation resistance of Sca1+ progenitors in an immortalized mammary gland cell line. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:468–477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gangemi R, Paleari L, Orengo AM, Cesario A, Chessa L, Ferrini S, Russo P. Cancer Stem Cells: A New Paradigm for Understanding Tumor Growth and Progression and Drug Resistance. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:1688–1703. doi: 10.2174/092986709788186147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zito G, Richiusa P, Bommarito A, Carissimi E, Russo L, Coppola A, Zerilli M, Rodolico V, Criscimanna A, Amato M, Pizzolanti G, Galluzzo A, Giordano C. In vitro identification and characterization of CD133(pos) cancer stem-like cells in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baas P, Belderbos JS, van den Heuvel M. Chemoradiation therapy in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:140–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328341eed6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honoki K. Do stem-like cells play a role in drug resistance of sarcomas? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:261–270. doi: 10.1586/era.09.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harper LJ, Costea DE, Gammon L, Fazil B, Biddle A, Mackenzie IC. Normal and malignant epithelial cells with stem-like properties have an extended G2 cell cycle phase that is associated with apoptotic resistance. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarkar B, Dosch J, Simeone DM. Cancer Stem Cells: A New Theory Regarding a Timeless Disease. Chem Rev. 2009;109:3200–3208. doi: 10.1021/cr9000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin F, Zhao L, Guo YJ, Zhao WJ, Zhang H, Wang HT, Shao T, Zhang SL, Wei YJ, Feng J, Jiang XB, Zhao HY. Influence of Etoposide on anti-apoptotic and multidrug resistance-associated protein genes in CD133 positive U251 glioblastoma stem-like cells. Brain Res. 2010;1336:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin F, Zhao L, Zhao HY, Guo SG, Feng J, Jiang XB, Zhang SL, Wei YJ, Fu R, Zhao JS. Paradoxical expression of anti-apoptotic and MRP genes on cancer stem-like cell isolated from TJ905 glioblastoma multiforme cell line. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:338–343. doi: 10.1080/07357900701788064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bartkowiak D, Stempfhuber M, Wiegel T, Bottke D. Radiation- and chemoinduced multidrug resistance in colon carcinoma cells. Strahlenther Onkol. 2009;185:815–820. doi: 10.1007/s00066-009-1993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kitazono M, Sumizawa T, Takebayashi Y, Chen ZS, Furukawa T, Nagayama S, Tani A, Takao S, Aikou T, Akiyama S. Multidrug resistance and the lung resistance-related protein in human colon carcinoma SW-620 cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1647–1653. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.19.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Figueiredo-Pontes LL, Pintao MC, Oliveira LC, Dalmazzo LF, Jacomo RH, Garcia AB, Falcao RP, Rego EM. Determination of P-glycoprotein, MDR-related protein 1, breast cancer resistance protein, and lung-resistance protein expression in leukemic stem cells of acute myeloid leukemia. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2008;74:163–168. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrow CS, Smitherman PK, Diah SK, Schneider E, Townsend AJ. Coordinated action of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) in antineoplastic drug detoxification. Mechanism of GST A1-1- and MRP1-associated resistance to chlorambucil in MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20114–20120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laborde E. Glutathione transferases as mediators of signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1373–1380. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mellor HR, Callaghan R. Resistance to chemotherapy in cancer: A complex and integrated cellular response. Pharmacology. 2008;81:275–300. doi: 10.1159/000115967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao J, Stapleton PL, Lin YS, Gallagher EP. Cytochrome p450 and glutathione s-transferase mRNA expression in human fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:168–175. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumanov A, Hayrabedyan S, Karaivanov M, Todorova K. Basal cell subpopulation as putative human prostate carcinoma stem cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2007;45:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allameh A, Esmaeli S, Kazemnejad S, Soleimani M. Differential expression of glutathione S-transferases P1-1 and A1-1 at protein and mRNA levels in hepatocytes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]