Abstract

The aim of this study was to elucidate the signaling pathway involved in the anti-aging effect of erythropoietin (EPO) and to clarify whether recombinant human EPO (rhEPO) affects apoptosis in the aging rat hippocampus by upregulating Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). In this study, a rat model of aging was established using D-galactose. Behavioral changes were monitored by the Morris water maze test. Using immunohistochemistry, we studied the expression of SIRT1, B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 gene (Bcl-2), and Bcl-2 associated X protein (Bax) expression, and apoptotic cells in the hippocampus of a rat model of aging in which rhEPO was intraperitoneally injected. The escape latency in rats from the EPO group shortened significantly; however, the number of platform passes increased significantly from that in the D-gal group (P < 0.05). Compared to the D-gal group, in the EPO group, the number of SIRT1 and Bcl-2-positive cells increased (P < 0.05), but the number of Bax-positive cells and apoptotic cells decreased in the hippocampus of aging rats (P < 0.05). These results suggest that rhEPO regulates apoptosis-related genes and affects apoptosis in the hippocampus of aging rats by upregulating SIRT. This may be one of the important pathways underlying the anti-aging property of EPO.

Keywords: Erythropoietin, aging, Sirtuin 1, B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 gene, Bcl-2 association X protein

Introduction

With the development of science and technology and advances in medicine, an aging population has become a pressing problem faced by human beings in the 21st century. The increase in the number of aging people places a heavy social and economic burden on the society and families. Therefore, delaying aging is an important subject for human development in the new century. As a multifunctional cytokine, the neuroprotective effect of erythropoietin (EPO) has become the focus of scientific research in recent years [1-4]. A few studies have shown that EPO can alleviate brain tissue damage caused by ischemia, improve learning, memory, and cognitive ability in patients with vascular dementia, and afford a major neuroprotective effect [5-7]. There were a few reports about its anti-aging effect; however, they were not systematic or detailed [8-10]. Our previous studies showed that recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) could improve learning and memory in the D-galactose-induced sub-acute rat model of aging by delaying the aging of the nervous system. Meanwhile, we have observed that it can reduce the ultrastructural changes and cell death caused by aging in the hippocampus [8,11]. However, the mechanism for this protective effect is not clear. As an important mechanism for neural cell death, apoptosis plays an important role in the aging process of the nervous system. Given that the Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog-1 (SIRT1) protein is a key link in the regulation of energy metabolism, redox conditions, cell apoptosis, and in prolonging life, the activity of SIRT1 protein in the cell achieves fine dynamic regulation of metabolism and internal environmental factors [12-14]. We already know that the SIRT1 protein is a key factor controlling the aging process in cells and that the apoptotic pathway is an important downstream channel. It is not clear whether exogenous EPO can cause an anti-aging effect by controlling SIRT1 protein expression in aged nerve cells, and by regulating apoptosis to reduce cell death. Therefore, based on previous studies, the effects of rhEPO on hippocampal SIRT1, Bcl-2, and Bax expression, and apoptotic cells in a D-galactose-induced aging-rat model were studied. We also explored whether rhEPO exerts its anti-aging effect by upregulating SIRT1 protein, increasing the expression of the antiapoptotic-protein Bcl-2, or reducing the expression of the apoptotic protein Bax. We further investigated the mechanisms underlying the anti-aging effect of rhEPO, the results of which may provide an important basis for clinical anti-aging drug research and development.

Materials and methods

Animals

Forty-eight Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (male) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of the Medical College of Xi’an Jiaotong University (SCXK (shan) 2007-001), each weighing 236.48 ± 9.01 g, and aged 2 months. They were divided into 4 groups (12 rats in each group). The rats were housed in a standard environment (22 ± 2°C with controlled humidity 55% ± 5%, 12-hour dark/light cycle) for 1 week. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal use protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Animal intervention

SD rats were allocated to four groups: sham-operated group (Sham), D-galactose group (D-gal), EPO intervention group (EPO), and vitamin E intervention group (VitE). The D-galactose, EPO intervention, and vitamin E intervention groups were administered 5% D-galactose (Amresco, OH, USA) (125 mg/kg, once/day) [15] by subcutaneous injection through the back of the neck for 6 weeks till the aging model was established; sham-operated group was administered normal saline (2.5 ml/kg, 1 time/day) similarly for 6 weeks. The EPO group was administered rhEPO (SUNSHINE, Shenyang, China) (3000 u/Kg.d) by intraperitoneal injection, since the model was made for 5 weeks; vitamin E intervention group was administered vitamin E (Sigma, Los Angeles, USA) (30 mg/Kg.d) to fill the stomach for a total of 2 weeks.

Morris water maze test

The Morris water maze test (MT-200, Taimeng Technology Co, Chengdu, China) was started on the third day of the sixth week of aging-induction; the first 5 days were utilized for training. The pool was divided into four quadrants and a 9 cm diameter platform was located 2 cm below the surface of the water in the center of the first quadrant. The animals were trained twice a day. The rats were put into the water facing the pool wall from each of the four different quadrants. The water temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1°C; the experimenter, location, and surrounding environment were kept the same. If the rat found the training platform within 60 s, the training was considered over; however, if the platform was not found within 60 s, rats were guided to the platform by the experimenters, and were allowed to remain on the platform for 10 s.

The tests began on the sixth day. Place navigation test: The rats were put into the water facing the pool wall at the center of the third quadrant. By using image acquisition and video tracking technology, the time needed to find the platform within 60 s (escape latency) was recorded; a duration over 60 s was recorded as 60 s. Probe trial test: The platform was removed and the rat was put into the water as described and the number of passes through the former position of the platform was recorded. Finally, using a water maze analysis software, the above two indicators, namely the escape latency (place navigation test) and number of platform passes (probe trial test) were analyzed.

Tissue preparation

The rats were anesthetized using 10% chloral hydrate (Guanghua Technology Co., Guangzhou, China) (3 mL/kg) after 1 week. A cannula was inserted into the ascending aorta via the left ventricle after thoracotomy. Heparinized saline and 4% paraformaldehyde (Guanghua Technology Co.) (0.01 mol/L) in phosphate-buffered saline (250 mL, room temperature) were infused through the atrium. The brains were quickly separated into cerebrum and cerebellum from behind the anterior margin of the optic chiasma, and then placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 14 hours. The specimens were dehydrated, permeabilized, and embedded in wax. The specimens were then sectioned (serially cut) into thick coronal slices (6 μm).

Nissl staining

The 6-μm paraffin sections were rinsed in xylene I and II for 15 min, incubated in 95% EtOH and 80% EtOH for 5 min each, and rinsed for 5 min in running water. After dewaxing, the sections were incubated in 1% toluidine blue (Tianyuan Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) at 55°C for 30 min, and subsequently rinsed for 5 min using distilled water. The sections were then incubated in 80% EtOH, 90% EtOH, and 95% EtOH for 5 min each followed by xylene I, II, and III for 15 min each [16]. Finally, the sections were mounted in neutral gum, and observed under an optical microscope (B-type biomicroscope, Global Motic Group, Xiamen, China).

Immunohistochemistry

The sections were hydrated after being deparaffinized. The antigen repaired for 10 min. The sections were incubated in rabbit anti-SIRT1 [17] (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA), rat anti-Bcl-2 [18] (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rat anti-Bax antibodies [19] (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Next, the sections were incubated at room temperature in biotinylated sheep anti-rabbit antibody (1:200; Zhongshanjinqiao Co., Beijing, China) for 40 min. The sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in streptavidin with horseradish peroxidase (1:200; Zhongshanjinqiao Co.), followed by diaminobenzidine chromogen for 5 min. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, and subsequently dehydrated and mounted. Images were collected and analyzed (Q550CW; Leica, Solms, Germany) from the motor cortex and the hippocampal CA1 region. Five different visual fields were randomly selected from each section for quantification under a light microscope (×400, B-type biomicroscope, Global Motic Group). The number of positive cells in each section was represented by a mean number.

TUNEL staining

The TUNEL staining [20] was performed according to the manufacturer’s specifications with an ApopTag Fluorescein in situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (BosterCo, Wuhan, China). Sections were treated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and digoxigenin-dNTP followed by incubation with anti-digoxigenin conjugated with fluorescein. The sections were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in anti-fluorescein antibody (1:200; BosterCo), followed by diaminobenzidine chromogen for 5 min. Counterstaining with DAPI was performed to visualize the nuclei. Cells with brown granules in their nuclei were regarded as apoptotic cells.

Statistical analysis

Using SPSS 17.0 statistical software for data analysis and processing, the two indicators were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (X̅ ± s), with Shapiro-Wilk method for test of normality, and Levene method to test for Homogeneity of Variance. α = 0.1, P > 0.1 indicated a normal distribution and equal variance of the data.

When the data (of normal distribution and equal variance) were compared between each group using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

When the data did not show a normal distribution or equal variance, the rank sum test of the Mann-Whitney U was used to compare the results between the groups. α = 0.05, P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Test results showed that the data (weight of rats before and after the building of model, number of platform passes, and the number of SIRT1, Bcl-2, Bax positive cells, and apoptotic cells) were normally distributed and conformed to the homogeneity of variance; therefore, the one-way ANOVA was used to compare between groups. Escape latency test data showed a non-normal distribution; therefore, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare between the two groups. For both the tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

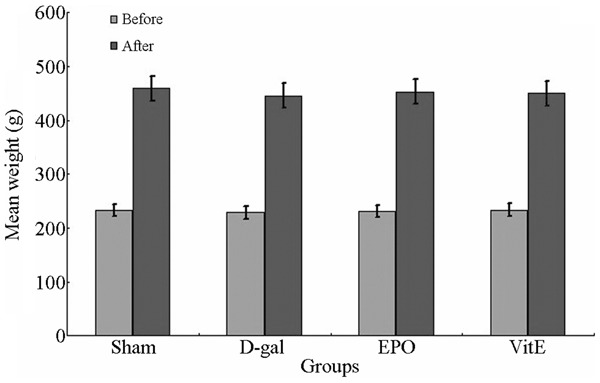

Body weights

Weights of the four groups of rats before and after building the model were not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The mean weight of each group of rats before and after model-making.

Behavioral changes

The Morris water maze test was used to observe the behavioral changes. In the place navigation test, compared with the rats in the sham group, the escape latency of the rats in the D-gal group increased significantly, while that in the rats in the EPO and VitE groups decreased significantly (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The behavioral changes in each group

| Groups | Escape latency/s | Crossing platform times/t |

|---|---|---|

| Sham | 18.56±11.87 | 3.67±1.61 |

| D-gal | 42.27±20.77a | 1.54±0.87a |

| EPO | 21.61±12.00b | 2.92±1.44b |

| VitE | 24.59±9.95b | 3.50±1.57b |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD; 12 rats in each group;

P < 0.05, vs. Sham group;

P < 0.05, vs. D-gal group.

Number of platform passes in the probe trial test in the D-gal group reduced significantly compared with the sham group. However, in the EPO and VitE groups, the number of platform passes increased significantly compared with the D-gal group (single factor ANOVA, P < 0.05) (Table 1).

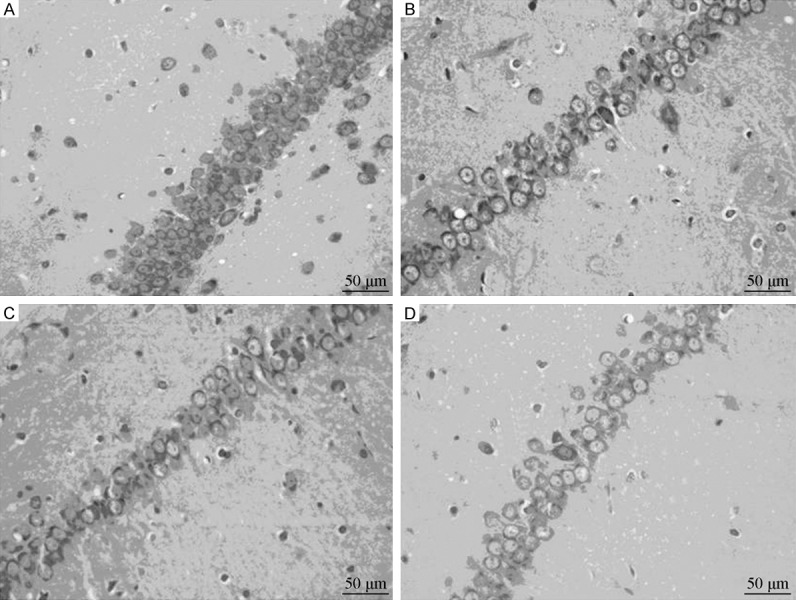

Nissl staining

Nissl staining results showed that the pyramidal neurons of hippocampal CA1 in the Sham group were arranged relatively linearly; Nissl bodies were abundant. However, in the D-gal group, the pyramidal neurons were larger and sparsely arranged, and the number of Nissl bodies was lower. The morphology of pyramidal neurons in the EPO and VitE groups was medial (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pyramidal neurons of hippocampal CA1 in different group. (Nissl staining, optical microscope, ×400). A: Sham group; B: D-gal group; C: EPO group; D: VitE group.

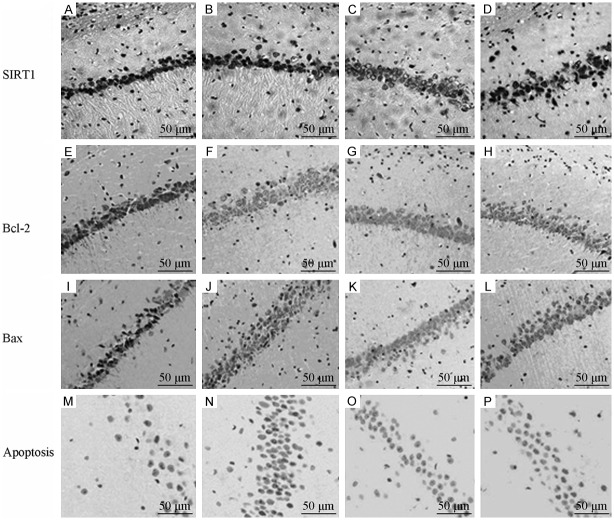

SIRT1 expression

The number of SIRT1-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the D-gal group increased compared with the sham group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The number of SIRT1-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 in the EPO and VitE groups increased significantly compared with the D-gal group (P < 0.05). The number of SIRT1-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the EPO group was more than that in the VitE group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Quantification of cells SIRT1, Bcl-2, Bax and apoptosis in CA1 region each group (400-fold visual field)

| Group | SIRT1 | Bcl-2 | Bax | Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 34.68±2.86 | 55.38±5.65 | 44.36±2.03 | 13.01±1.30 |

| D-gal | 36.20±3.37 | 67.35±5.32a | 59.56±3.83a | 50.06±5.67a |

| EPO | 66.22±5.54b,c | 84.78±5.48b,c | 48.48±2.73b | 25.38±3.02b,c |

| VitE | 50.80±6.20b | 74.18±7.48b | 49.54±2.23b | 38.27±3.56b |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD; 10 rats in each group.

P < 0.05, vs. Sham group;

P < 0.05, vs. D-gal group;

P < 0.05, vs. VitE group; (analysis of variance).

Figure 3.

Expression of SIRT1, Bcl-2, Bax and apoptosis in CA1 region each group (immunohistochemistry, TUNEL staining, ×400). A: Sham group; B: D-gal group; C: EPO group; D: VitE group.

Bcl-2 and Bax

The Bcl-2-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the D-gal group increased significantly compared with the sham group (P < 0.05). The number of Bcl-2-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the EPO and VitE groups increased significantly compared to the D-gal group (P < 0.05). The number of Bcl-2-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the EPO group was significantly more than that in the VitE group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Figure 3).

The Bax-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the D-gal group increased significantly compared with the sham group (P < 0.05); however, it decreased significantly in the EPO and VitE groups compared with the D-gal group (P < 0.05). The number of Bax-positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the EPO and VitE groups was not significantly different (P > 0.05) (Table 2; Figure 3).

Apoptotic cells

The apoptotic cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the D-gal group increased significantly compared with the sham group (P < 0.05); however, compared to the D-gal group, it decreased significantly in the EPO and VitE groups (P < 0.05). The number of apoptotic cells in the hippocampal CA1 region in the EPO group was lesser than that in the VitE group (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Figure 3).

Discussion

With the rapid increase in the elderly population, aging has become a social problem affecting the development of society and economy. The apoptosis theory is currently being intensely studied and is widely being accepted as a theory of aging. The theory states that apoptosis or programmed cell death, which is induced by stimuli such as hypoxia and drugs, occurs in the body spontaneously, and active cell death is achieved by the regulation of apoptosis related genes. The aging of the nervous system is one of the main effects of aging. Studies have confirmed that neural cell senescence is caused by the apoptosis of nerve cells, thus, apoptosis plays an important role in the aging of the nervous system [21-23].

Traditional theory holds that EPO, a hematopoietic stimulating factor secreted by cells around the kidney renal tubule, can stimulate erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow to differentiate and become mature. It has been found in recent years that EPO is a multifunctional cytokine secreted by every organ in the body, such as the heart, brain, and lungs, that plays a very important role in maintaining basic physiological functions and homeostasis; its role especially in the nervous system has attracted the most attention. Studies confirm that EPO can alleviate brain tissue damage caused by ischemia, and improve learning, memory, and cognitive ability in patients with vascular dementia and has an important neuroprotective effect [1-7]. Our previous studies have shown that EPO can improve learning and memory in a D-galactose-induced sub-acute rat model of aging and reduce the changes in the ultrastructure of the hippocampus caused by aging. EPO also increases the total content of antioxidant enzymes and superoxide dismutase in the brain tissue, which can have a potential anti-aging effect on the nervous system [8,11]. This study sought to elucidate the mechanism of the anti-aging effect of EPO by observing the changes in the expression of apoptosis related indices in the rat hippocampal CA1 area.

Building an aging animal model is the key step to evaluate the anti-aging effects of EPO. In this experiment, the D-galactose-induced rat model of aging, which is a domestically recognized aging model widely used in studies of anti-aging drugs, was used. This model is created by injecting animals with large doses of galactose, which causes similar symptoms and manifestations to natural aging, such as abnormal gene expression, decline in cell growth, low immunity, and cognitive dysfunction. Although rats live longer than other organisms used in aging studies (e.g., yeast or nematodes) and it is not easy to evaluate anti-aging effects due to their lifespan, the rat as a mammal has a similar metabolic structure and genetic background to the higher mammals. Therefore, using rats to establish an animal-aging model to explore the anti-aging effects of EPO is of potentially great clinical value. Finally, this study utilized the D-galactose dosage data from a previous study [15], by using 5% D-galactose (125 mg/kg, subcutaneously injected for six weeks) for the preparation of the D-galactose rat model of aging.

Due to the lack of specificity in changes during aging, evaluation of the animal-aging models lacks absolute indicators. Although animal lifespan is regarded as the golden standard for evaluating anti-aging effects, it is inconvenient to evaluate the lifespans of rats and other mammals in short-term experiments. This study investigated the anti-aging effect of EPO on the nervous system. Therefore, we chose the water maze experiment to evaluate the cognitive function of rats as an indirect evaluation method.

Morris water maze was first designed by the British psychologist Morris. It is now widely used to study neurobiological mechanisms in learning and memory research [24]. The Classic Morris water maze experiment includes the place navigation and probe trial tests. The place navigation test is performed by setting the rats from each of the four different quadrants into a whirlpool and recording the time the rats spend to find a platform hidden below the surface of the water (the escape latency). The rats are trained twice a day for 5 days and are tested on the sixth day. The probe trial test is performed by removing the platform and then recording the swimming trajectory of the rat and its frequency of passes through the former position of the platform in a specified time. Finding the platform is an extremely complex memory process in rats, which involves the collection of spatial location information, followed by sorting, handling, processing, and outputting the information. Therefore, Morris water maze can be used to examine spatial learning and memory ability in rats.

In this study, the escape latency period (from the place navigation test) in the D-gal group was significantly longer than that in the Sham group. However, the frequency of platform crossings was smaller in the D-gal group than in the Sham group, indicating the decline in the cognitive ability of the aging rats. It also indicated that we had built a successful animal model.

In addition to evaluating the animal model by praxeology, the study also used Nissl staining to observe the morphology of the rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons to evaluate whether the aging model was successful. A Nissl body is a basophilic material in neurons, consisting mainly of rough endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes, which can synthesize a variety of proteins and enzymes necessary for the maintenance of the cells. In the physiological state, abundant and large Nissl bodies indicate that the process of protein synthesis in the neuron is exuberant; when the neurons are damaged, the number of Nissl bodies decrease. Nissl staining is a common staining method used to observe neurons. The tinctorial Nissl bodies are in blocks or granular and those surrounding the nucleus are bigger while those near the edge of the cell are small and slender. Therefore, Nissl staining allows the understanding of the structure as well as damage of neurons through the observation of the tinctorial Nissl bodies. In our study, Nissl staining showed that the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in aging rats are bigger and sparser, and the number of intracytoplasmic Nissl bodies were significantly lower. Therefore, an aging model built was successfully as shown through the study of cell morphology.

In our preliminary studies with the D-galactose-induced subacute rat model of aging, we supplemented different doses of rhEPO (1000, 3000, 5000 U/kg) and using behavioral, molecular biology, and tissue morphology experiments determined the dose that had the best anti-aging effect. The medium dose (3000 U/kg) of rhEPO clearly improved learning and memory in the aging rats, partially inhibited the increase of MDA levels in the liver and brain, and slowed down hippocampal changes in aging such as the deposition of lipofuscin and decrease of neuron numbers, nuclear deformation, and swelling and decrease of organelles. These effects show that rhEPO has a potential anti-aging effect in the nervous system. The study also showed that T-AOC and SOD levels in the brain tissue of the rats significantly decreased after being administered a medium dose of rhEPO. Therefore, we can preliminarily infer that rhEPO enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, improves the organism’s total antioxidant capacity, and reduces the damage by free radicals and other reactive oxygen species caused to molecules, cells, and tissues. It also exerts its anti-aging effects by reducing the generation of oxidative stress products thus avoiding detrimental effects on the function of large molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, improving the ability of learning and reduces memory decline, and improving the decreased function of tissues and organs caused by aging [8,11].

Based on previous studies, this study utilized vitamin E, which is recognized as having an anti-aging effect, to establish a positive control group. Therefore, the anti-aging effect of rhEPO on learning and memory ability in rats and on hippocampal neurons was evaluated by utilizing the Morris water maze experiment and Nissl staining of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, respectively, Additionally, the number of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells and the extent of cell loss improved clearly compared with aging rats. These results are similar to previous findings, further showing that EPO has a protective effect on the nervous system of D-galactose-induced animal-aging model.

In 1934, Mccay’s team found that restricting the food supply to rats did not lead to malnutrition; instead, it made the rats live longer. Similar phenomenon was reported in studies on yeast, worms, fruit flies, and higher mammals. The molecular mechanism of caloric restriction affecting aging and the related anti-aging strategy increasingly grabbed the attention of academic circles, thus open up a new field of aging research. Kaeberlein’s group working on yeast found important molecules, which mediate the life extension effect of calorie restriction. One of them, the silent information regulator protein 2 (Sir2 protein), is also the first member of the sirtuin family. The yeast Sir2 protein is an inhibitory protein tangled on extrachromosomal rDNA; a higher expression of Sir2 can prolong lifetime [25]. The homologous protein of Sir2 in mammals is sirtuin. At least seven homologues of the sirtuin protein (SIRT1-SIRT7) are currently known in mammals. These proteins are composes of approximately 275 amino acids and possess NAD+ dependent acetylation enzyme activity and/or ADP ribose transferase activity. Among these homologous proteins, the SIRT1 protein is the most studied. SIRT1 has NAD+ dependent protein acetylation activity and through a variety of signaling pathways, it participates in the regulation of cellular energy and redox states. From an evolutionary perspective, the SIRT1 protein is a highly conservative cell defensive protein, ensuring survival in case of insufficient supply of energy, through the regulation of metabolism. Therefore, SIRT1 is the key link in the process of energy metabolism regulation, redox conditions, cell apoptosis, and prolonging life, the activity of SIRT1 protein in the cell get fine dynamic regulation of metabolism and environmental factors. The levels of SIRT1 protein can be regulated by post-translational modifications and translation, while at the same time being affected by NAD+ and other factors that influence SIRT1 protease activity. Under the conditions of calorie restriction and hunger, the SIRT1 protein expression increases. However, with a high-fat diet, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and in the process of aging, SIRT1 protein expression decreases [12,14]. It is not clear whether exogenous EPO can regulate SIRT1 protein expression in aged nerve cells. Based on these, the current study elucidated the expression of SIRT1 protein in the nerve cells in the hippocampal CA1 area of aging rats after rhEPO intervention. The results show that SIRT1 protein expression was much higher in the EPO (especially) and VitE groups than in the D-gal group. First, EPO increases the expression of SIRT1 proteins in the aging nerve cells. SIRT1 protein regulates the expression of downstream genes and plays a role in the oxidative damage caused by D-galactose. Second, EPO increases SIRT1 function more than VitE, which indicates that EPO affords a stronger protection from oxidative damage caused by D-galactose. However, the pathway involved in this protective effect is still unclear.

The existing apoptosis theory suggests that aging is a spontaneous and self-initiated process in the cells, namely creature from develop to aging, the body that have time to arrange in advance, this time is called the “clock”, determined by the genetic program. Apoptosis is also known as programmed cell death, which is a cell-activated and spontaneous death regulated by apoptosis-related genes. As a basic life phenomenon, apoptosis plays a significant role in the aging process of the body. The apoptotic pathways can be divided into the receptor-mediated apoptotic signaling pathway and the endogenous apoptotic pathway. The endogenous apoptosis pathway is regulated by the intracellular Bcl-2 family. Krajewska et al. [26] and others found that in developing mice, from embryonic day 6, Bcl-2 and Bax show a diffused expression in the central nervous system, which peaks on day 11, and after lasting 15 days the expression gradually declines, and is then maintained at a low level at the time of birth. In the Bcl-2 family, the balance between the Bcl-xl and Bax plays an important role in early development of the central nervous system. Bcl-xl knockout embryonic mice do not survive and have a large number of apoptotic cells in the central nervous system. However, although Bax knockout embryonic rat do not survive, their central nervous system do not have a large number of apoptotic cells. This indicated that the Bax gene could reverse a large number of cell apoptosis caused by Bcl-xl knockout [27]. Lindsten et al. [28] and others found that when the Bax and Bak genes are knocked out simultaneously, the number of mouse neural progenitor cells increase significantly and their normal distribution is disrupted. In addition, Bax genes have been found to be closely associated with cell apoptosis caused by the lack of nutrients, i.e., after knocking out the Bax gene, cultured sympathetic neurons in vitro can tolerate lack of nutrients without causing apoptosis. All these studies suggest that the Bcl-2 family members play an important and complicated role in the development of the nervous system and neuronal apoptosis. We already know that the SIRT1 protein is a key regulator in the cellular aging process, and cell apoptotic pathway is an important downstream channel [29-32]. Whether the SIRT1 protein upregulated by EPO, causes a chain reaction in the downstream apoptotic cells, is not clear. Based on this, we further used the same model to study if the expression of the apoptosis-related genes Bcl-2 and Bax is regulated by EPO through the upregulation of SIRT1 proteins. Meanwhile, we observed the number of apoptotic cells through TUNEL staining. The results showed that the expression of the apoptosis inhibiting protein Bcl-2 in the rat hippocampal CA1 area increased significantly compared with the D-gal group, and the expression of the apoptosis promoting protein Bax decreased significantly compared with the D-gal group. In addition, the apoptotic cell numbers decrease significantly. The results from the vitamin E group (positive control) are consistent with the rhEPO intervention group, suggests that rhEPO may upregulate SIRT1 protein expression, further upregulating the expression of downstream antiapoptotic-protein Bcl-2, and inhibiting the expression of the proapoptotic protein Bax. In addition, compared with the vitamin E group, in the EPO group, the expression of the antiapoptotic-protein Bcl-2 in the hippocampal CA1 region increased significantly, and the expression of the proapoptotic protein Bax did not show any significant difference. In addition, the number of apoptotic cells reduced significantly. It can be inferred that, compared to vitamin E, rhEPO may mainly excerpt its anti-aging effect by increasing the expression of the antiapoptotic-protein Bcl-2.

In conclusion, using a rat model of aging, this study shows that rhEPO protects the nervous system from the effects of aging. Additionally, it upregulates the SIRT1 protein and controls downstream apoptosis related genes, and reduces apoptosis in aging rat-hippocampal cells. It may be one of the important pathways in the anti-aging effect of EPO.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (The mechanism of erythropoietin-TAT regulating Keap l-Nrf2 pathway on anti-aging process in nerve, 2011), No. 81170330.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Noguchi CT, Asavaritikrai P, Teng R, Jia Y. Role of erythropoietin in the brain. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;64:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Xing J, Liou AK, Wang S, Gan Y, Luo Y, Ji X, Stetler RA, Chen J, Cao G. Enhanced delivery of erythropoietin across the blood-brain barrier for neuroprotection against ischemic neuronal injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2010;1:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J, Li G, Zhang Y, Su X, Hang C. The potential role of JAK2/STAT3 pathway on the anti-apoptotic effect of recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) after experimental traumatic brain injury of rats. Cytokine. 2011;56:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponce LL, Navarro JC, Ahmed O, Robertson CS. Erythropoietin neuroprotection with traumatic brain injury. Pathophysiology. 2013;20:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang F, Wang S, Cao G, Gao Y, Chen J. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 5 contributes to erythropoietin-mediated neuroprotection against hippocampal neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang S, Liu X, Fu P, Gong W, Yan F, Han P, Ding Y, Ji X, Luo Y. Neuroprotection by local intra-arterial infusion of erythropoietin after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurol Res. 2011;33:520–528. doi: 10.1179/016164111X13007856084287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang SQ, Zhao F, Zhao ZQ, Xie XW. Effect of erythropoietin (EPO) on plasticity of nervous synapse in CA1 region of hippocampal of vascular dementia (VaD) rats. Afr J Pharm and Pharmacol. 2012;6:1111–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhai YF, Wu HQ, Lü D, Wang HQ, Wang HY, Zhang GL. The Anti-aging Effect of EPO and the Preliminary Probe into Its Mechanisms. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;43:679–682, 719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung YH, Kim SI, Joo KM, Kim YS, Lee WB, Yun KW, Cha CI. Age-related changes in erythropoietin immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rats. Brain Res. 2004;1018:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. Erythropoietin: New Directions for the Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:11102–11129. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhai Y, Wang H, Wang H, Sun H, Zhang G, Wu H. Effect of erythropoietin on activities of antioxidant enzymes in the brain tissue of aged rats. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33:1332–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JE, Chen J, Lou Z. DBC1 is a negative regulator of SIRT1. Nature. 2008;451:583–586. doi: 10.1038/nature06500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamovich Y, Shlomai A, Tsvetkov P, Umansky KB, Reuven N, Estall JL, Spiegelman BM, Shaul Y. The protein level of PGC-1α, a key metabolic regulator, is controlled by NADH-NQO1. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;33:2603–2613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01672-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revollo JR, Li X. The ways and means that fine tune Sirt1 activity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao GX, Deng HB, Yuan LG, Li DD, Li YY, Wang Z. Protective Role of Salidroside against Aging in A Mouse Model Induced by D-galactose. Biomed Environ Sci. 2010;23:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0895-3988(10)60047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Wu H, Guo H, Zhang G, Zhang R, Zhan SQ. Increased hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha expression in rat brain tissues in response to aging. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:778–782. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H, Kim KR, Noh SJ, Park HS, Kwon KS, Park BH, Jung SH, Youn HJ, Lee BK, Chung MJ, Koh DH, Moon WS, Jang KY. Expression of DBC1 and SIRT1 is associated with poor prognosis for breast carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong M, Cheng GQ, Ma SM, Yang Y, Shao XM, Zhou WH. Post-ischemic hypothermia promotes generation of neural cells and reduces apoptosis by Bcl-2 in the striatum of neonatal rat brain. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xi HJ, Zhang TH, Tao T, Song CY, Lu SJ, Cui XG, Yue ZY. Propofol improved neurobehavioral outcome of cerebral ischemia–reperfusion rats by regulating Bcl-2 and Bax expression. Brain Res. 2011;1410:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan Y, Guo H, Ye Z, Pingping X, Wang N, Song Z. Ischemic postconditioning protects brain from ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through PI3K-Akt pathway. Brain Res. 2011;1367:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lockshin RA. Programmed cell death: history and future of a concept. J Soc Biol. 2005;199:169–173. doi: 10.1051/jbio:2005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan J, Yankner BA. Apoptosis in the nervous system. Nature. 2000;407:802–809. doi: 10.1038/35037739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higami Y, Shimokawa I. Apoptosis in the aging process. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s004419900156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2570–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krajewska M, Mai JK, Zapata JM, Ashwell KW, Schendel SL, Reed JC, Krajewski S. Dynamics of expression of apoptosis regulatory protein Bid, Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, and Bak during development of murine nervous system. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:145–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chipuk JE, McStay GP, Bharti A, Kuwana T, Clarke CJ, Siskind LJ, Obeid LM, Green DR. Sphingolipid metabolism cooperates with BAK and BAX to promote the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 2012;148:988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsten T, Ross AJ, King A, Zong WX, Rathmell JC, Shiels HA, Ulrich E, Waymire KG, Mahar P, Frauwirth K, Chen Y, Wei M, Eng VM, Adelman DM, Simon MC, Ma A, Golden JA, Evan G, Korsmeyer SJ, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu M, Zhang P, Chen M, Zhang W, Yu L, Yang XC, Fan Q. Aging might increase myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis in humans and rats. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:621–632. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9259-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixit D, Sharma V, Ghosh S, Mehta VS, Sen E. Inhibition of Casein kinase-2 induces p53-dependent cell cycle arrest and sensitizes glioblastoma cells to tumor necrosis factor (TNFα)-induced apoptosis through SIRT1 inhibition. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e271. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seo JS, Moon MH, Jeong JK, Seol JW, Lee YJ, Park BH, Park SY. SIRT1, a histone deacetylase, regulates prion protein-induced neuronal cell death. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1110–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng X, Liang N, Zhu D, Gao Q, Peng L, Dong H, Yue Q, Liu H, Bao L, Zhang J, Hao J, Gao Y, Yu X, Sun J. Resveratrol inhibits β-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis through regulation of SIRT1-ROCK1 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]