Abstract

Within the past several years, inhibition of the PARP1 activity has been emerged as one of the most exciting and promising strategies for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) therapy. The purpose of this study is to assess PARP1 expression in TNBCs and to evaluate the association between polymorphisms in PARP1 promoter or 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) and PARP1 expression. It was found that PARP1 was overexpressed in nuclear (nPARP1), cytoplasm (cPARP1) and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting (coPARP1) of 187 TNBCs in comparison to that of 115 non-TNBCs (nPARP1, p<0.001; cPARP1, p<0.001; coPARP1, p<0.001). High expression of nPARP1 and cPARP1 in breast cancer was related to worse progression-free survival (nPARP1, p=0.007, cPARP1, p=0.003). Additionally, we identified seven published polymorphism sites in the promoter region and in 3’UTR of PARP1 by sequencing. rs7527192 and rs2077197 genotypes were found to be significantly associated with the cPARP1 expression in TNBC patients (rs7527192 AA+GA versus GG, p=0.014; rs2077197 AA+GA versus GG, p=0.041). These findings were confirmed in an independent validation set of 88 TNBCs (rs7527192 GG versus GA+AA, p=0.030; rs2077197 GG versus GA+AA, p=0.030). The PARP1 over-expression including nuclear, cytoplasm and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting is a feature of TNBCs and the assessment of its expression may help to predict the efficacy of chemotherapy with PARP1 inhibitor.

Keywords: PARP1, polymorphism, SNP, promoter, 3’UTR, TNBC

Introduction

The poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1), also known as poly [ADP-ribose] synthase 1 or NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase 1, is an abundant cellular enzyme involved in DNA repair, genomic stability control, cell metabolic regulation, cell death and proliferation [1-4]. It could be activated by broken DNA strands and has a major role in DNA single strand break (SSB) repair [5-8]. Its activation leads to the synthesis of large branching chains of poly (ADP-ribose) homopolymers attached to both PARP1 itself and other proteins at the vicinity of the breaks, thereby gathering the DNA damage repair machinery [9]. As a result of compromised repair, PARP1 deficient or inhibited cells are more sensitive to DNA damaging. For example, PARP-/- mice treated either by the DNA alkylating agent N-methyl-N-nitrosourea or by gamma-irradiation demonstrated an extreme sensitivity in cell damage and a high genomic instability to both agents [10].

In breast cancer models, PARP1 inhibition agents could selectively kill cells with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, which normally encode proteins critical for DNA homologous recombination repair [11,12]. One proposed mechanism is that PARP1 inhibiter blocks SSB repair and leads to the formation of unrepaired DSBs (double strand breaks) at the replication fork. Therefore, cells with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations have been shown to be highly sensitive to PARP1 inhibition, resulting in cell death by apoptosis [13]. Recently, inhibition of PARP1 activity with small molecules is emerging as one of the most exciting and promising strategies for BRCA hereditary breast cancer therapy [11,12,14-17].

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subset of breast cancer with a biological phenotype similar to BRCA-defective and therefore may be sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors [18,19]. O’Shaughnessy et al conducted an open-label, phase 2 study to compare the efficacy and safety of gemcitabine and carboplatin with or without PARP1 inhibitor iniparib in metastatic TNBC patients and reported clinical benefit in 56% of the patients who received chemotherapy plus the iniparib [20]. However, this clinical trial and other ongoing trials did not take the internal level of PARP1 into consideration [21,22]. Domagala et al analyzed the PARP1 expression in Polish breast cancer patients and found low PARP1 expression was present in 21% of BRCA1-associated TNBCs and in 2.7% of non-BRCA1-associated TNBCs [23]. It has been reported that PARP1 mRNA level was up-regulated in TNBCs compared with receptor-positive breast cancer tissues [24,25]. Both diffuse and marked nuclear and cytoplasmic immunostaining of PARP were detected by immunohistochemistry in breast cancer tissues [23,26]. The significant of PARP1 expression in different localization detected by immunohistochemistry is still controversial and the biologic role of nPARP1 and cPARP1 is currently not clear.

This study was undertaken to assess the expression of PARP1 in breast cancer patients in TNBC and non-TNBC. In addition, we sequenced the promoter and 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) of PARP1 and evaluated the association of PARP1 expression and the polymorphism of single nucleotide in these regions.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

This study included samples from two groups of female patients: 187 TNBCs (99 in training set and 88 validation set) and 115 non-TNBCs. Among 214 training set patients, 99 TNBCs and 115 non-TNBCs, who were diagnosed with breast cancer between Jan 2010 and Nov 2011. 88 TNBCs in validation set were diagnosed from Jan 2012 to Jan 2013. All breast cancer surgical specimens were collected from Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute & Hospital. No endocrine therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy was offered to patients before surgery. Fresh tissue specimens were frozen shortly after resection and stored at -80°C and all their archived, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy samples were available for immunohistochemistry. Histologic types were defined according to the WHO classification. All of them were diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified type (NOS-IDC) types. Histologic grading was carried out using the modified Bloom and Richardson grading system [27]. All the patients were ethnic Han Chinese. Patient’s consent for research was obtained prior to surgery and the study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethical Committee.

The median age of the patients was 52 years old (range 29-76). From Jan 2010, clinical follow-up date of 214 training set patients were analyzed. The patients were followed up for 18-48 months with a median of 40 months, during which 1.9% (4/214) patients suffered local or regional tumor recurrence, 13.6% (29/214) developed distant metastasis.

PARP1 immunohistochemistry and quantification

Immunohistochemistry for PARP1 was performed using standard procedures. Briefly, 4-μm tissue sections were subsequently dewaxed and rehydrated using xylene and graded alcohol washes. Antigen retrieval was performed at 121°C for 2 min, using citrate buffer (pH 6.0). After serial blocking with hydrogen peroxide and normal goat serum, the sections were incubated with primary monoclonal antibody against PARP1 (1:300 dilution, clone F-2, sc-8007, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 16 h at 4°C. The sections were then sequentially incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin and peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (DAKO). The enzyme substrate was 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetra-hydrochloride. Incubation of sections with phosphate-buffered saline only served as negative controls.

The immunohistochemistry was independently assessed by two pathologists who were blinded to PARP1 genotypes and clinico-pathological data. In cases of disagreement, the result was resolved by consensus. We employed the multiplicative quickscore method (QS) to assess the nuclear expression of PARP1 proteins (nPARP1) [28]. This system accounts for both the intensity and the extent of cell staining. In brief, the proportion of positive cells was estimated and given a percentage score on a scale from 1 to 6 (1 = 1-4%; 2 = 5-19%; 3 = 20-39%; 4 = 40-59%; 5 = 60-79%; and 6 = 80-100%). The average intensity of the positively staining cells was given an intensity score from 0 to 3 (0 = no staining; 1 = weak, 2 = intermediate, and 3 = strong staining). The QS was then calculated by multiplying the percentage score by the intensity score to yield a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 18. Based on the QS, nuclear and PARP1 expression was graded as low (0-9) or high (10-18). For cytoplasmic PARP1 expression and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting unequivocal staining in ≥1% cells was graded as positive.

Immunohistochemistry for molecular subtypes

Additional immunohistochemistry for molecular subclassification of the tumors was performed on serial tissue sections of the corresponding formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks using the standard procedures. Primary antibodies against ER (clone SP1, 1:150 dilution, Zymed, San Francisco, CA), PR (clone SP2, 1:150 dilution, Zymed), and HER2 (DAKO HercepTestTM, Denmark,), Ki-67 (clone SP6, 1:200 dilution, ThermoScientific, Fremont CA), EGFR (clone 31G7, 1:100 dilution, Zymed), and CK5/6 (clone D5/16B4, 1:100 dilution, Zymed) were applied according to manufacturer’s instructions. ER and PR were determined by immunohistochemistry establishing positivity criteria in ≥1% of nuclear tumor staining [29]. Interpretation and scoring of HER2, Ki-67, EGFR, and CK5/6 staining described by Cheang et al were adopted in our study [30]. Confirmatory fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation using Vysis kit (Vysis, Inc., Downers Grove, IL) was pursued on those tumors with a 2+ HER2 expression by immunohistochemistry.

Breast cancer molecular subtypes were defined as follows: luminal A (ER positive and/or PR positive, and Ki-67 <14%), luminal B (ER positive and/or PR positive and Ki-67 ≥14%), luminal-HER2 (ER positive and/or PR positive and HER2 positive), HER2enriched (ER negative, PR negative and HER2 positive), and basal-like (ER negative, PR negative, HER2 negative, and EFGR and/or CK5/6 positive). In addition, triple-negative tumors (TNP, negative for ER, PR and HER2) that were negative for both EGFR and CK5/6 were classified as TNP-nonbasal [31].

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA from breast tumor tissues was isolated using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA quantity was measured by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA). DNA samples were stored at -80°C.

DNA sequencing and genotyping

PARP1 promoter or 3’UTR was amplified using Platinum Taq system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PARP1 promoter primer Forward 5’-GGG GAG AGA GGA CAC ACT TAA GA-3’, Reverse 5’-TTC CCG GAC ACA GTT AAC CC-3’; 3’UTR primer Forward 5’-ggc tgt tgg ctc ctt aac aa-3’, Reverse 5’-tct ggg gtt tca cag att aag g-3’. Cycle sequencing reactions were performed according to the conventional Sanger’s dideoxy chain termination method using ABI 96-capillary 3730XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystem, USA). The results were analyzed by ABI Variant Reporter v1.1 software.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 13.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Analysis of differences in distributions of PARP1 expression between the two groups of patients was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test and among more than two groups were evaluated by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Chi-square Test/Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare the distributions of polymorphisms between TNBCs and non-TNBCs, as well as when compare the PARP1 expression between different SNP genotypes. Progression-free survival (PFS) was considered from the date of surgery to the date of any primary, regional or distant recurrence, as well as the appearance of a secondary tumor or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Univariate analysis was based on the Kaplan-Meier DFS curves using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed for the identification of relevant prognostic factors. A 2-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the analyses.

Results

PARP1 expression detected by immunohistochemistry

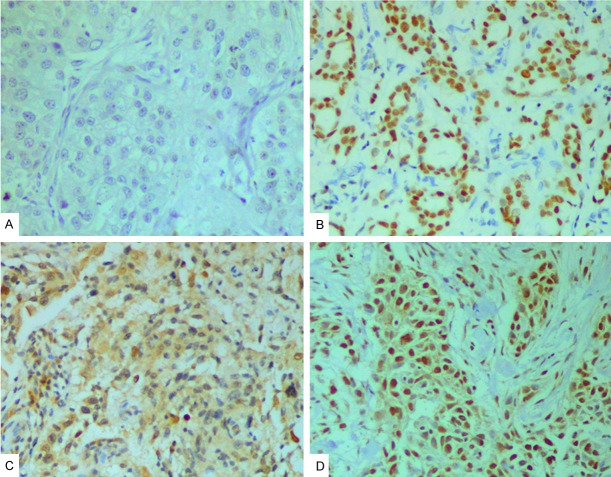

As shown in Figure 1, tumor samples showed different nuclear (nPARP1) and cytoplasmic (cPARP1) PARP1 expression patterns, which were categorized as low/high (nuclear) or negative/positive (cytoplasmic), as recently described [23]. In a number of cancers (99/302, 32.8%) both cytoplasmic and nuclear expression (coPARP1) was seen. Expression level of nPARP1 in invasive breast cancer cells was high in 165 samples (54.6%), and low in 137 samples (45.4%). cPARP1 expression level was positive in 152 samples (50.3%), and negative in 150 samples (49.7%).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of PARP1 in breast cancer samples (original magnification ×200). A: No staining; B: High expression of nuclear PARP1 (nPARP1); C: Positive expression of cytoplasmic PARP1 (cPARP1); D: Nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting (coPARP1) in breast cancer samples.

PARP1 expression in TNBCs and non-TNBCs

Associations of PARP1 with clinicopathological features of breast cancer patients were shown in Table 1. High nPARP1 expression was identified in 61.5% (115/187) of TNBCs and in 43.5% (50/115) of non-TNBCs, with nPARP1 expression significantly higher in TNBCs than in non-TNBCs (p<0.001). High nPARP1 were associated with negative ER (p=0.012), negative PgR (p=0.009) and negative HER2 (p=0.034). In addition, significant difference in the nPARP1 level was identified among the different molecular subtypes of breast cancer (p=0.033). Positive cPARP1 was observed in 58.8% (110/187) of TNBCs and in 36.5% (42/115) of non-TNBCs, with the expression significantly higher in TNBCs than in non-TNBCs (p<0.001). It was also noted that cPARP1 expression was associated with ER and PgR negative status (ER, p<0.001; PR, p<0.001), as well as with molecular subtypes (p=0.002). The nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting was seen in 32% (99/302) of all cases. coPARP1 correlated with triple negative status (p<0.001), ER (p<0.001) and PgR negative status (p<0.001), and molecular subtypes (p<0.001). Other clinicopathological parameters did not show a significant association or correlation with PARP1 expression.

Table 1.

Correlation of PARP1 expression in tumor tissues with clinicopathologic characteristics in breast cancer patients

| Factor | All Patients | Low nPARP1 | High nPARP1 | Comparison of nPARP1 Levels, p | Negative cPARP | Positive cPARP | Comparison of cPARP1 Levels, p | Negative coPARP1 | Positive coPARP1 | Comparison of coPARP1 Levels, p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| All patients | 302 | 100 | 137 | 45.4 | 165 | 54.6 | 150 | 49.7 | 152 | 50.3 | 203 | 67.2 | 99 | 32.8 | |||

| Triple negative status | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||||||||||||

| TNBC | 187 | 61.9 | 72 | 38.5 | 115 | 61.5 | 77 | 41.2 | 110 | 58.8 | 111 | 59.4 | 76 | 40.6 | |||

| non-TNBC | 115 | 38.1 | 65 | 56.5 | 50 | 43.5 | 73 | 63.5 | 42 | 36.5 | 92 | 80.0 | 23 | 20.0 | |||

| Age, years | 0.25* | 0.485* | 0.354* | ||||||||||||||

| <50 | 141 | 46.7 | 59 | 41.8 | 82 | 58.2 | 67 | 47.5 | 74 | 52.5 | 91 | 64.5 | 50 | 35.5 | |||

| ≥50 | 161 | 53.3 | 78 | 48.4 | 83 | 51.6 | 83 | 51.6 | 78 | 48.4 | 112 | 69.6 | 49 | 30.4 | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.561* | 0.666* | 0.165* | ||||||||||||||

| ≤2 | 88 | 29.1 | 38 | 43.2 | 50 | 56.8 | 42 | 47.7 | 46 | 52.3 | 54 | 61.4 | 34 | 38.6 | |||

| >2 | 214 | 70.9 | 99 | 46.3 | 115 | 53.7 | 108 | 50.5 | 106 | 49.5 | 149 | 69.6 | 65 | 30.4 | |||

| Tumor grade | 0.223* | 0.744* | 0.894* | ||||||||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 212 | 70.2 | 101 | 47.6 | 111 | 52.4 | 104 | 49.1 | 108 | 50.9 | 143 | 67.5 | 69 | 32.5 | |||

| 3 | 90 | 29.8 | 36 | 40.0 | 54 | 60.0 | 46 | 51.1 | 44 | 48.9 | 60 | 66.7 | 30 | 33.3 | |||

| Nodal status | 0.793* | 0.422* | 0.272* | ||||||||||||||

| N0 | 148 | 49.0 | 66 | 44.6 | 82 | 55.4 | 77 | 52.0 | 71 | 48.0 | 95 | 64.2 | 53 | 35.8 | |||

| N+ | 154 | 51.0 | 71 | 46.1 | 83 | 53.9 | 73 | 47.4 | 81 | 52.6 | 108 | 70.1 | 46 | 29.9 | |||

| ER status | 0.012* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||||||||||||

| Negative | 195 | 64.6 | 78 | 40.0 | 117 | 60.0 | 81 | 41.5 | 114 | 58.5 | 116 | 59.5 | 79 | 40.5 | |||

| Positive | 107 | 35.4 | 59 | 55.1 | 48 | 44.9 | 69 | 64.5 | 38 | 35.5 | 87 | 81.3 | 20 | 18.7 | |||

| PR status | 0.009* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||||||||||||

| Negative | 198 | 65.6 | 79 | 39.9 | 119 | 60.1 | 82 | 41.4 | 116 | 58.6 | 118 | 59.6 | 80 | 40.4 | |||

| Positive | 104 | 34.4 | 58 | 55.8 | 46 | 44.2 | 68 | 65.4 | 36 | 34.6 | 85 | 81.7 | 19 | 18.3 | |||

| HER2 status | 0.034* | 0.604* | 0.983* | ||||||||||||||

| Negative | 253 | 83.8 | 108 | 42.7 | 145 | 57.3 | 124 | 49.0 | 129 | 51.0 | 170 | 67.2 | 83 | 32.8 | |||

| Positive | 49 | 16.2 | 29 | 59.2 | 20 | 40.8 | 26 | 53.1 | 23 | 46.9 | 33 | 67.3 | 16 | 32.7 | |||

| Proliferation (Ki-67) | 0.566* | 0.492* | 0.15* | ||||||||||||||

| Low proliferation (<20%) | 105 | 34.8 | 50 | 47.6 | 55 | 52.4 | 55 | 52.4 | 50 | 47.6 | 80 | 76.2 | 25 | 23.8 | |||

| High proliferation (≥20%) | 197 | 65.2 | 87 | 44.2 | 110 | 55.8 | 95 | 48.2 | 102 | 51.8 | 123 | 62.4 | 74 | 37.6 | |||

| Molecular subtype | 0.033† | 0.002† | <0.001† | ||||||||||||||

| luminal A | 32 | 10.6 | 16 | 50.0 | 16 | 50.0 | 22 | 68.8 | 10 | 33.2 | 30 | 93.8 | 2 | 6.2 | |||

| luminal B | 34 | 11.3 | 20 | 58.8 | 14 | 41.2 | 25 | 73.5 | 9 | 26.5 | 29 | 85.3 | 5 | 14.7 | |||

| luminal-HER2 | 43 | 14.2 | 25 | 58.1 | 18 | 41.9 | 22 | 51.2 | 21 | 48.8 | 28 | 65.1 | 15 | 34.9 | |||

| HER2 enriched | 6 | 2.0 | 4 | 66.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 66.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 5 | 83.2 | 1 | 16.7 | |||

| basal-like | 176 | 58.3 | 70 | 39.8 | 106 | 60.2 | 72 | 40.9 | 104 | 59.1 | 107 | 60.8 | 69 | 39.2 | |||

| TNP-non basal | 11 | 3.6 | 2 | 18.2 | 9 | 81.8 | 5 | 45.5 | 6 | 54.5 | 4 | 36.4 | 7 | 63.6 | |||

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Prognostic significance of PARP1 expression

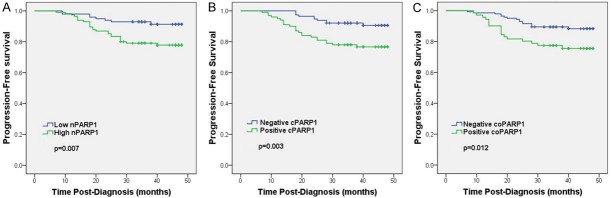

In the univariable Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, high PARP1 expression including nuclear, (nPARP1, p=0.007) (Figure 2A) cytoplasmic (cPARP1, p=0.003) (Figure 2B) and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting (coPARP1, p=0.012) (Figure 2C) in 214 breast cancer patients was found to be an unfavorable prognostic factor measured by PFS. Multivariate cox-regression analysis confirmed that high PARP1 expression was an unfavorable predictor of PFS (nPARP1, p=0.017; cPARP1, p=0.043) except nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting (p=0.980), in addition to the demonstration of prognostic significance of tumor grade and axillary lymph node status. Tumor HER2 oncogene expression was an indicator for worse PFS (p=0.042) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) curves for breast cancer patients based on PARP1 expression. A: PFS cures of breast cancer patients based on the expression of nuclear PARP1 (nPARP1); B: PFS cures of breast cancer patients based on the expression of cytoplasmic PARP1 (cPARP1); C: PFS cures of breast cancer patients based on the nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting (coPARP1). The breast cancer patients with high nPARP1, positive cPARP1 and positive nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting showed significantly poorer PFS rates than respective opposite group.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of pathologic features and PARP1 expression for PFS in breast cancer

| Variable | PFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years) (<50 vs. ≥50) | 0.98 | 0.47-2.06 | 0.952 |

| Tumor size (cm) (≤2 vs. >2) | 2.17 | 1.52-3.10 | <0.001 |

| Lymph node (negative vs. positive) | 4.13 | 1.891-9.03 | <0.001 |

| Histological grade (I vs. II-III) | 3.14 | 1.40-7.03 | 0.005 |

| ER status (negative vs. positive) | 0.78 | 0.08-7.20 | 0.528 |

| PR status (negative vs. positive) | 0.51 | 0.06-4.24 | 0.528 |

| HER2 status (negative vs. positive) | 2.88 | 1.04-7.98 | 0.042 |

| nPARP1 expression (low vs. high) | 2.94 | 1.21-7.13 | 0.017 |

| cPARP1 expression (negative vs. positive) | 2.51 | 1.03-6.12 | 0.043 |

| coPARP1 expression (negative vs. positive) | 1.01 | 0.43-2.39 | 0.980 |

PFS, progression-free survival; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazardratio; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

SNPs in PARP1 promoter and its association with PARP1 expression

Using conventional Sanger sequencing method, we screened PARP1 promoter region among TNBC and non-TNBC patients. Four published single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (rs7527192, rs2077197, rs7531668, rs907187) were identified and no significant differences in the allele or genotype frequencies were observed between TNBCs and non-TNBCs (Table 3). However, rs7527192 and rs2077197 genotypes were significantly associated with the cPARP1 expression in TNBC patients (rs7527192 AA+GA versus GG, p=0.014; rs2077197 AA+GA versus GG, p=0.041) (Table 4).

Table 3.

PARP1 Promoter and 3’UTR SNPs in Patients With TNBC or non-TNBC

| All | TNBC | non-TNBC | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| SNP genotype | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |

| rs7527192 (G>A) | |||||||

| GG | 104 | 48.6 | 47 | 47.5 | 57 | 49.6 | |

| GA | 80 | 37.4 | 36 | 36.4 | 44 | 38.3 | |

| AA | 30 | 14.0 | 16 | 16.2 | 14 | 12.2 | 0.704† |

| GG vs GA+AA | 0.785* | ||||||

| rs2077197 (G>A) | |||||||

| GG | 104 | 48.6 | 47 | 47.5 | 57 | 49.6 | |

| GA | 83 | 38.3 | 38 | 38.4 | 45 | 39.1 | |

| AA | 27 | 12.6 | 14 | 14.1 | 13 | 11.3 | 0.821† |

| GG vs GA+AA | 0.785* | ||||||

| rs7531668 (T>A) | |||||||

| TT | 108 | 50.5 | 49 | 49.5 | 59 | 51.3 | |

| TA | 80 | 37.4 | 35 | 35.4 | 45 | 39.1 | |

| AA | 26 | 12.1 | 15 | 15.2 | 11 | 9.6 | 0.448† |

| TT vs TA+AA | 0.891* | ||||||

| rs907187 (G>C) | |||||||

| GG | 76 | 35.5 | 41 | 41.4 | 35 | 30.4 | |

| GC | 93 | 43.5 | 38 | 38.4 | 55 | 47.8 | |

| CC | 45 | 21.0 | 20 | 20.2 | 25 | 21.7 | 0.228† |

| GG vs GC+CC | 0.115* | ||||||

| rs1330613 (G>A) | |||||||

| GG | 193 | 90.2 | 85 | 85.9 | 108 | 93.9 | |

| GA | 21 | 9.8 | 14 | 14.1 | 7 | 6.1 | 0.065* |

| rs8679 (T>C) | |||||||

| TT | 179 | 83.6 | 81 | 81.8 | 98 | 85.2 | |

| TC | 35 | 16.4 | 18 | 18.2 | 17 | 14.8 | 0.580* |

| rs3219149 (G>T) | |||||||

| GG | 191 | 89.3 | 84 | 84.8 | 107 | 93.0 | |

| GT | 23 | 10.7 | 15 | 15.2 | 8 | 7.0 | 0.075* |

Chi-squared test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Table 4.

Association of PARP1 Promoter Genotypes With PARP1 Expression in Patients With TNBC or non-TNBC

| SNP genotype | Low nPARP1 | High nPARP1 | Comparison Of nPARP1 Levels, P | Negative cPARP1 | Positive cPARP1 | Comparison Of cPARP1 Levels, P | Negative coPARP1 | Positive coPARP1 | Comparison of coPARP1 Levels, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7527192 (G>A) | |||||||||

| All | |||||||||

| GG | 50 | 54 | 48 | 56 | 65 | 39 | |||

| GA+AA | 49 | 61 | 0.681 | 66 | 44 | 0.055 | 28 | 32 | 0.192 |

| TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 15 | 32 | 13 | 34 | 26 | 21 | |||

| GA+AA | 19 | 33 | 0.676 | 28 | 24 | 0.014* | 36 | 16 | 0.153 |

| non-TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 35 | 22 | 35 | 22 | 39 | 18 | |||

| GA+AA | 30 | 28 | 0.349 | 38 | 20 | 0.701 | 42 | 16 | 0.639 |

| rs2077197 (G>A) | |||||||||

| All | |||||||||

| GG | 50 | 54 | 49 | 55 | 66 | 38 | |||

| GA+AA | 49 | 61 | 0.681 | 65 | 45 | 0.100 | 77 | 33 | 0.310 |

| TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 15 | 32 | 14 | 33 | 27 | 20 | |||

| GA+AA | 19 | 33 | 0.676 | 27 | 25 | 0.041* | 35 | 17 | 0.311 |

| non-TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 35 | 22 | 35 | 22 | 39 | 18 | |||

| GA+AA | 30 | 28 | 0.349 | 38 | 20 | 0.701 | 42 | 16 | 0.639 |

| rs7531668 (T>A) | |||||||||

| All | |||||||||

| TT | 50 | 58 | 52 | 56 | 68 | 40 | |||

| TA+AA | 49 | 57 | 1.000 | 62 | 44 | 0.135 | 75 | 31 | 0.226 |

| TNBC | |||||||||

| TT | 14 | 35 | 16 | 33 | 28 | 21 | |||

| TA+AA | 20 | 30 | 0.291 | 25 | 25 | 0.103 | 34 | 16 | 0.264 |

| non-TNBC | |||||||||

| TT | 36 | 23 | 36 | 23 | 40 | 19 | |||

| TA+AA | 29 | 27 | 0.351 | 37 | 19 | 0.699 | 41 | 15 | 0.525 |

| rs907187 (G>C) | |||||||||

| All | |||||||||

| GG | 38 | 38 | 45 | 31 | 50 | 26 | |||

| GC+CC | 61 | 77 | 0.474 | 69 | 69 | 0.202 | 93 | 45 | 0.812 |

| TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 16 | 25 | 19 | 22 | 23 | 18 | |||

| GC+CC | 18 | 40 | 0.520 | 22 | 36 | 0.416 | 39 | 19 | 0.259 |

| non-TNBC | |||||||||

| GG | 22 | 13 | 26 | 9 | 27 | 8 | |||

| GC+CC | 43 | 37 | 0.417 | 47 | 33 | 0.142 | 54 | 26 | 0.297 |

Fisher’s exact test.

In an independent TNBC validation set (88 TNBCs), rs7527192 and rs2077197 were also found to be associated with the cPARP1 expression (rs7527192 GG versus GA+AA, p=0.030; rs2077197 GG versus GA+AA, p= 0.030, Table 5).

Table 5.

Association of PARP1 Promoter Genotypes With PARP1 Expression in an Independent TNBC Validation Set

| SNP genotype | Low nPARP1 | High nPARP1 | Comparison Of nPARP1 Levels, P | Negative cPARP1 | Positive cPARP1 | Comparison Of cPARP1 Levels, P | Negative coPARP1 | Positive coPARP1 | Comparison of coPARP1 Levels, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7527192 (G>A) | |||||||||

| GG | 19 | 28 | 14 | 33 | 30 | 17 | |||

| GA+AA | 19 | 22 | 0.668 | 22 | 19 | 0.030* | 30 | 11 | 0.348 |

| rs2077197 (G>A) | |||||||||

| GG | 18 | 29 | 14 | 33 | 30 | 17 | |||

| GA+AA | 20 | 21 | 0.390 | 22 | 19 | 0.030* | 30 | 17 | 0.348 |

Fisher’s exact test.

Prognostic significance of rs7527192 and rs2077197 in TNBCs

Although rs7527192 and rs2077197 genotypes were significantly associated with the cPARP1 expression in TNBC patients. In the univariable Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, the two genotypes were not demonstrated to be a significant prognostic indicator (PFS, p=0.521 and p=0.288 respectively).

SNPs in PARP1 3’UTR and its association with PARP1 expression

Three published SNPs (rs13306133, rs8679, rs3219149) were identified in PARP1 3’UTR. No significant differences in genotype frequencies were observed between TNBCs and non-TNBCs (Table 3). SNP sites in 3’UTR could affect gene expression by blocking miRNA binding the target sites [31,32]. Thus we analyzed the correlation between 3’UTR SNP genotype and PARP1 level in all patients. No significant association was observed between PARP1 levels and 3’UTR SNP genotyping (date not shown).

Discussion

We aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of PARP1 expression in breast cancer and to evaluate the potential impact of polymorphisms on PARP1 promoter and 3’UTR by assessing the expression of PARP1 in different SNP types. Our findings can be summarized as follows: (1) The PARP1 over-expression including nuclear, cytoplasmic and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting is a feature of TNBCs; and (2) High expression of nPARP1 and cPARP1 in breast cancer were related to worse PFS. (3) Certain single nucleotide polymorphisms in PARP1 promoter may predict cPARP1 over-expression.

Breast cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among female cancer patients worldwide. Diagnosed in an estimated 180,000 women each year worldwide, TNBC is an aggressive subtype of breast cancer that bears a biological phenotype similar to BRCA-defective breast cancer [19]. It has unique molecular characteristics of lacking ER, PR, and HER2 expression, often with early metastases and a relative lack of targeted therapeutics. Targeting DNA repair pathway, PARP1 inhibitors were originally exploited to treat breast cancer patients with BRCA mutations [11,12,14-17]. The encouraging results promoted the clinical investigators to explore the anti-cancer effect of PARP1 inhibitors in TNBC. It has been widely accepted that sporadic TNBCs and BRCA-associated breast cancers share several characteristics, and sporadic TNBCs appear to have a ‘BRCA-ness’. In sporadic TNBCs, BRCA1-promoter hypermethylation or overexpression of its negative regulators could lead to BRCA1 dysregulation [33-36]. In addition, defects in homologous recombination pathways, such as ATM, p53, PALB2 and MRE11-RAD50-NBS1, have been implicated in tumor genesis of TNBCs [37-40]. Thus, PARP1 inhibitors alone, or in combination with DNA-damaging chemotherapy is a promising therapeutics for TNBCs. Several clinical trials were conducted to assess the potential anti-cancer effect of PARP1 inhibitors (BSI 201 and Olaparib) in BRCA or TNBC breast cancers [20,22,41]. However, in these ongoing trials the internal level of PARP1 was not taken into consideration [21,22]. Targeted therapy (such as Herceptin) depends on the presence or overexpression of target protein in tumor tissues. In the case of PARP1 inhibitor treatment for TNBCs, the expression of PARP1 protein in tumor tissue should be taken into account. We have shown that PARP1 was overexpressed in a larger proportion TNBCs compared with non-TNBCs and high PARP1 expression was associated with negative hormone receptor status. These findings revealed high PARP1 expression was a reliable feature of TNBCs. The study results will help to screen breast cancer patients suitable for PARP1 inhibitor therapy.

Previous studies have been conducted to evaluate the PARP1 expression in breast cancer tissues [23-25,42-44]. Gonçalves et al performed a meta-analysis on a large public retrospective gene expression data set (n=2,485) to analyze PARP1 mRNA levels in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer and found PARP1 was overexpressed in basal samples compared to other subtypes [25]. Similarly, Ossovskaya et al revealed that the negative expression of ER, PgR and HER2 was associated with the upregulation of PARP1 mRNA expression [24]. However, PARP1 mRNA level can not predict nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of the PARP1 enzyme. Using immunohistochemical staining, we demonstrated that cytoplasmic and nuclear expression levels were associated with negative hormone receptor status. Studies by Rojo et al [26] confirmed that nuclear PARP1 is overexpressed in TNBCs and predicts poor prognosis in operable invasive breast cancer. Additionally, Minckwitz et al have described cytoplasmic PARP expression was higher in TNBCs [42]. Indeed, our study indicates that nPARP1, cPARP1 and nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting of PARP1 were significantly associated with worse PFS. Multivariate Cox-regression analysis confirmed that high nPARP1 and cPARP1 expression but not nuclear-cytoplasmic coexisting were unfavorable predictors of PFS. These findings revealed that PARP1 was a reliable indicator of aggressive behavior in breast cancer and high PARP1 expression is a marker in breast cancer could warrant a poor patient outcome.

Three hundred and thirty-one SNPs, including twenty coding SNPs, have been reported in PARP1 gene [45]. A common T-to-C polymorphism (rs1136410, T2444C) which leads to a Val762Ala substitution at PARP1 catalytic domain could reduce PARP1 activity by 30-40% [45-47]. A meta-analysis showed that the rs1136410 variant (C) allele was significantly associated with increased risk of cancer in the Chinese [48]. SNPs in gene promoter region could have an impact on gene expression mainly by influencing the binding affinity of transcription factors [49-51]. For example, -783 G and -1438 G allele in 5-HT2A receptor gene promoter region are known to reduce the binding activity of transcription factors [49]. In this study, we hypothesize that polymorphisms in PARP1 promoter may influence PARP1 protein expression. We sequenced the promoter region of PARP1 gene and identified four published SNP sites (rs7527192, rs2077197, rs7531668, rs907187). Among these sites, rs7527192 and rs2077197 genotypes were significantly associated with the cPARP1 expression in TNBC patients. Our finding provides novel data on the relationship between polymorphisms in PARP1 promoter region and PARP1 expression in breast cancer tissues.

miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides that negatively regulate gene expression, primarily by partially complementary binding to the 3’UTR of target messenger RNA (mRNA); this leads to mRNA cleavage or translation repression [52]. SNPs within miRNA binding sites could alter translation of target mRNA [32,53]. For example, a SNP site located in let-7 binding site among the KRAS 3’UTR could lead to overexpression of KRAS [53]. Teo et al showed that homozygotes of miRNA-binding site SNP in PARP1 3’UTR (rs8679) were associated with an increased breast cancer risk [54]. In present study, we identified three SNP sites among PARP1 3’UTR (rs8679, rs3219149, rs13306133). All these three SNPs have no significant association with PARP1 expression.

This study is limited to clinical observations, and we lack information on long-term clinical follow-up date and the possible correlation between PARP1 expression levels and response to PARP1 inhibitors. Further studies are required to investigate the biological functions of PARP1 in different subcellular localization. In conclusion, PARP1 expression evaluated by immunohistochemistry in TNBCs and non-TNBCs indicated that their over-expression is a feature of TNBCs and the assessment of its expression may help to predict the efficacy of chemotherapy with PARP1 inhibitor. Furthermore, we identify that certain single nucleotide polymorphisms in PARP1 promoter may predict cPARP1 over-expression. The study results will help to screen breast cancer patients suitable for PARP1 inhibitor therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) [2009CB521700]; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [20110490788]; Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education [20131202120002]; and Key Program of Chinese National Natural Science Foundation [30930038]; partially by grants from Program for Chang jiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of Ministry of Education of China [IRT0743] and Chinese National Natural Science Foundation [30800355, 81202101, 81172531]; as well as Innovation Funding for graduate of Tianjin Medical University, third phase of the 211 Project for Higher Education [Grant No. 2010GSI17].

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- PARP1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- 3’UTR

3’ untranslated region

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PgR

progesterone receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- miRNA

microRNA

References

- 1.Jagtap P, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and the therapeutic effects of its inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:421–440. doi: 10.1038/nrd1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji Y, Tulin AV. The roles of PARP1 in gene control and cell differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai P, Canto C. The role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 enzymes in metabolic regulation and disease. Cell Metab. 2012;16:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson BA, Kraus WL. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrm3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dantzer F, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Flatter E, De La Rubia G, Oliver J, Rolli V, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in base excision repair. Biochimie. 1999;81:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dantzer F, de La Rubia G, Menissier-De Murcia J, Hostomsky Z, de Murcia G, Schreiber V. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi0003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu B, Yap TA, Molife LR, de Bono JS. Targeting the DNA damage response in oncology: past, present and future perspectives. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:316–324. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835280c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pears CJ, Couto CA, Wang HY, Borer C, Kiely R, Lakin ND. The role of ADP-ribosylation in regulating DNA double-strand break repair. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:48–56. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herceg Z, Wang ZQ. Functions of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in DNA repair, genomic integrity and cell death. Mutat Res. 2001;477:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Murcia JM, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Ricoul M, Dutrillaux B, Mark M, Oliver FJ, Masson M, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Walztinger C, Chambon P, de Murcia G. Requirement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in recovery from DNA damage in mice and in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7303–7307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, Ashworth A. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashworth A. A synthetic lethal therapeutic approach: poly(ADP) ribose polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of cancers deficient in DNA double-strand break repair. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:3785–3790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plummer R. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition: a new direction for BRCA and triple-negative breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:218. doi: 10.1186/bcr2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O’Connor MJ, Ashworth A, Carmichael J, Kaye SB, Schellens JH, de Bono JS. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inbar-Rozensal D, Castiel A, Visochek L, Castel D, Dantzer F, Izraeli S, Cohen-Armon M. A selective eradication of human nonhereditary breast cancer cells by phenanthridine-derived polyADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R78. doi: 10.1186/bcr2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frizzell KM, Kraus WL. PARP inhibitors and the treatment of breast cancer: beyond BRCA1/2? Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:111. doi: 10.1186/bcr2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan AR, Swain SM. Therapeutic strategies for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer J. 2008;14:343–351. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d839b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartsch R, Ziebermayr R, Zielinski CC, Steger GG. Triple-negative breast cancer. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2010;160:174–181. doi: 10.1007/s10354-010-0773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Shaughnessy J, Osborne C, Pippen JE, Yoffe M, Patt D, Rocha C, Koo IC, Sherman BM, Bradley C. Iniparib plus chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:205–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domagala P, Lubinski J, Domagala W. Iniparib in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1101855. author reply 1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler RK, Wardley A, Mitchell G, Earl H, Wickens M, Carmichael J. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domagala P, Huzarski T, Lubinski J, Gugala K, Domagala W. PARP-1 expression in breast cancer including BRCA1-associated, triple negative and basal-like tumors: possible implications for PARP-1 inhibitor therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:861–869. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ossovskaya V, Koo IC, Kaldjian EP, Alvares C, Sherman BM. Upregulation of Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 (PARP1) in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Other Primary Human Tumor Types. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:812–821. doi: 10.1177/1947601910383418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goncalves A, Finetti P, Sabatier R, Gilabert M, Adelaide J, Borg JP, Chaffanet M, Viens P, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 mRNA expression in human breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rojo F, Garcia-Parra J, Zazo S, Tusquets I, Ferrer-Lozano J, Menendez S, Eroles P, Chamizo C, Servitja S, Ramirez-Merino N, Lobo F, Bellosillo B, Corominas JM, Yelamos J, Serrano S, Lluch A, Rovira A, Albanell J. Nuclear PARP-1 protein overexpression is associated with poor overall survival in early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1156–1164. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detre S, Saclani Jotti G, Dowsett M. A “quickscore” method for immunohistochemical semiquantitation: validation for oestrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:876–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, Hicks DG, Lester S, Love R, Mangu PB, McShane L, Miller K, Osborne CK, Paik S, Perlmutter J, Rhodes A, Sasano H, Schwartz JN, Sweep FC, Taube S, Torlakovic EE, Valenstein P, Viale G, Visscher D, Wheeler T, Williams RB, Wittliff JL, Wolff AC. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheang MC, Chia SK, Voduc D, Gao D, Leung S, Snider J, Watson M, Davies S, Bernard PS, Parker JS, Perou CM, Ellis MJ, Nielsen TO. Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:736–750. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voduc KD, Cheang MC, Tyldesley S, Gelmon K, Nielsen TO, Kennecke H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1684–1691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sethupathy P, Borel C, Gagnebin M, Grant GR, Deutsch S, Elton TS, Hatzigeorgiou AG, Antonarakis SE. Human microRNA-155 on chromosome 21 differentially interacts with its polymorphic target in the AGTR1 3’ untranslated region: a mechanism for functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:405–413. doi: 10.1086/519979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baldassarre G, Battista S, Belletti B, Thakur S, Pentimalli F, Trapasso F, Fedele M, Pierantoni G, Croce CM, Fusco A. Negative regulation of BRCA1 gene expression by HMGA1 proteins accounts for the reduced BRCA1 protein levels in sporadic breast carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2225–2238. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2225-2238.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beger C, Pierce LN, Kruger M, Marcusson EG, Robbins JM, Welcsh P, Welch PJ, Welte K, King MC, Barber JR, Wong-Staal F. Identification of Id4 as a regulator of BRCA1 expression by using a ribozyme-library-based inverse genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:130–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esteller M, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Bonilla F, Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, Bussaglia E, Prat J, Harkes IC, Repasky EA, Gabrielson E, Schutte M, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:564–569. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS, Russell AM, Springall RJ, Ryder K, Steele D, Savage K, Gillett CE, Schmitt FC, Ashworth A, Tutt AN. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tommiska J, Bartkova J, Heinonen M, Hautala L, Kilpivaara O, Eerola H, Aittomaki K, Hofstetter B, Lukas J, von Smitten K, Blomqvist C, Ristimaki A, Heikkila P, Bartek J, Nevanlinna H. The DNA damage signalling kinase ATM is aberrantly reduced or lost in BRCA1/BRCA2-deficient and ER/PR/ERBB2-triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2501–2506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heikkinen T, Karkkainen H, Aaltonen K, Milne RL, Heikkila P, Aittomaki K, Blomqvist C, Nevanlinna H. The breast cancer susceptibility mutation PALB2 1592delT is associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3214–3222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartkova J, Tommiska J, Oplustilova L, Aaltonen K, Tamminen A, Heikkinen T, Mistrik M, Aittomaki K, Blomqvist C, Heikkila P, Lukas J, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J. Aberrations of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 DNA damage sensor complex in human breast cancer: MRE11 as a candidate familial cancer-predisposing gene. Mol Oncol. 2008;2:296–316. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.BiPar Sciences presents interim phase 2 results for PARP inhibitor BSI-201 at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2–3. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.1.7613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Minckwitz G, Muller BM, Loibl S, Budczies J, Hanusch C, Darb-Esfahani S, Hilfrich J, Weiss E, Huober J, Blohmer JU, du Bois A, Zahm DM, Khandan F, Hoffmann G, Gerber B, Eidtmann H, Fend F, Dietel M, Mehta K, Denkert C. Cytoplasmic poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase expression is predictive and prognostic in patients with breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2150–2157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozretic L, Rhiem K, Huss S, Wappenschmidt B, Markiefka B, Sinn P, Schmutzler RK, Buettner R. High nuclear poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase expression is predictive for BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:4586–4588. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1988. author reply 4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domagala P, Huzarski T, Lubinski J, Gugala K, Domagala W. Immunophenotypic predictive profiling of BRCA1-associated breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0988-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang XG, Wang ZQ, Tong WM, Shen Y. PARP1 Val762Ala polymorphism reduces enzymatic activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cottet F, Blanche H, Verasdonck P, Le Gall I, Schachter F, Burkle A, Muiras ML. New polymorphisms in the human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 coding sequence: lack of association with longevity or with increased cellular poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation capacity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2000;78:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s001090000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lockett KL, Hall MC, Xu J, Zheng SL, Berwick M, Chuang SC, Clark PE, Cramer SD, Lohman K, Hu JJ. The ADPRT V762A genetic variant contributes to prostate cancer susceptibility and deficient enzyme function. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6344–6348. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pabalan N, Francisco-Pabalan O, Jarjanazi H, Li H, Sung L, Ozcelik H. Racial and tissue-specific cancer risk associated with PARP1 (ADPRT) Val762Ala polymorphism: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:11061–11072. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers RL, Airey DC, Manier DH, Shelton RC, Sanders-Bush E. Polymorphisms in the regulatory region of the human serotonin 5-HT2A receptor gene (HTR2A) influence gene expression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim BC, Kim WY, Park D, Chung WH, Shin KS, Bhak J. SNP@Promoter: a database of human SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) within the putative promoter regions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blank MC, Stefanescu RN, Masuda E, Marti F, King PD, Redecha PB, Wurzburger RJ, Peterson MG, Tanaka S, Pricop L. Decreased transcription of the human FCGR2B gene mediated by the -343 G/C promoter polymorphism and association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Genet. 2005;117:220–227. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chin LJ, Ratner E, Leng S, Zhai R, Nallur S, Babar I, Muller RU, Straka E, Su L, Burki EA, Crowell RE, Patel R, Kulkarni T, Homer R, Zelterman D, Kidd KK, Zhu Y, Christiani DC, Belinsky SA, Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB. A SNP in a let-7 microRNA complementary site in the KRAS 3’ untranslated region increases non-small cell lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8535–8540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teo MT, Landi D, Taylor CF, Elliott F, Vaslin L, Cox DG, Hall J, Landi S, Bishop DT, Kiltie AE. The role of microRNA-binding site polymorphisms in DNA repair genes as risk factors for bladder cancer and breast cancer and their impact on radiotherapy outcomes. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:581–586. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]