Abstract

Ewing’s sarcoma is the second most common pediatric bone tumor. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma occurring in the cerebral cranium is exceptionally rare, with only one reported case of multiple tumor lesions in adolescence to date. We report a case of a 5-year-old male patient with multiple primary Ewing’s sarcomas associated with the cranial bones, the first pediatric case report to date. We also review 71 cases Ewing’s sarcoma involving intracranial extension. The purpose of this article is to provide data concerning the clinical and therapeutic course of multiple primary Ewing’s sarcomas in associated with cerebral cranium.

Keywords: Primary Ewing’s sarcoma, cerebral cranium

Introduction

Ewing’s sarcoma, which belongs to a large family of small-blue-round-cell tumors, is the second most common bone tumor in children. Ninety percent of these cases occur in the first or second decade of life. It arises anywhere in the entire body, and based on its origin, it is defined as osseous or extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma. Osseous Ewing’s sarcoma arises most frequently in the long bones of limbs and ribs as well as flat bones, including the pelvis [1,2].

Primary Ewing’s sarcoma in the cranial bones is uncommon and constitutes approximately 1% of all Ewing’s sarcoma [1]. Primary Ewing’s sarcomas occurring in the cerebral cranium (including frontal, temporal, occipital, parietal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones) are extremely rare and only 71 cases (1 with multiple lesions and 70 with single lesion) involving intracranial extension have been reported in the English literature, to the best of our knowledge. We report a case of a 5-year-old male patient with multiple lesions of primary Ewing’s sarcoma in the cranial bones, which is the first reported in the literature to date. The purpose of this report is to provide data concerning the clinical and therapeutic course of this case.

Case report

A 5-year-old male presented with rapidly enlarging and swollen left frontoparietal region for a period of 2 months, accompanied by progressive diminution of vision in the left eye. On physical examination, a non-tender, firm swelling measuring 5 cm × 5 cm mass was noted over the frontoparietal region. It was hard and immobile to the scalp and underlying bone. He was noted to have light perception and loss of pupillary light responses in the left eye.

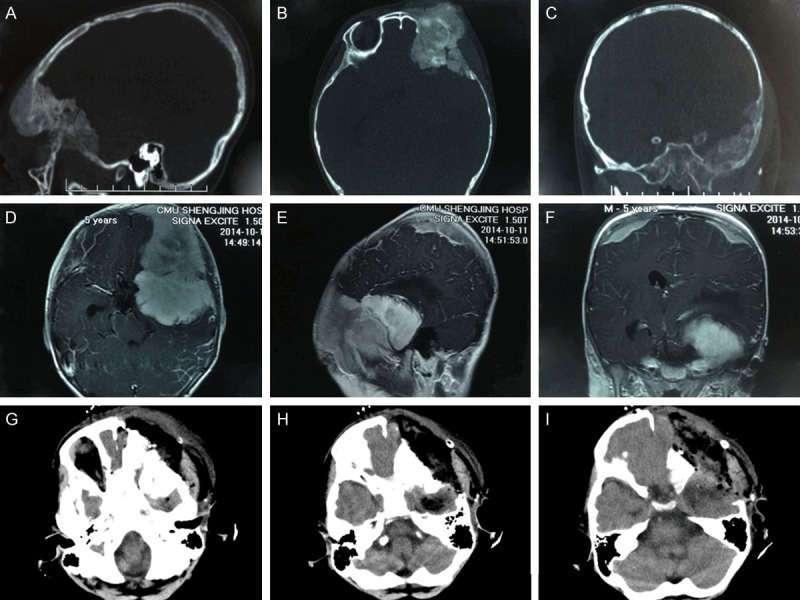

The computed tomography (CT) scan showed a hyperdense mass lesion in the greater sphenoid wing extending into the left orbital cavity, middle cranial fossa, and temporal fossa. The mass was poorly defined with normal bone. In addition, destruction and thickening of biparietal bones were seen. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed three tumor masses with hypointense on T1-weighted scan and hypointense on T2 weighted scan. The sizes of masses in the anterior and middle cranial fossa and biparietal bones were 9 cm × 7 cm × 5.5 cm, 5 cm × 5 cm × 2 cm and 5 cm × 5 cm × 1.5 cm, respectively. The tumor in the skull base compressed the frontal brain parenchyma and distorted the corpus callosum and the anterior cerebral arteries (Figure 1). Further metastatic evaluation using technetium-99 whole body bone scan preoperatively demonstrated abnormal uptake in the biparietal and the left frontoparietal regions, which was consistent with the MRI findings. There was no uptake lesion beyond the cranium.

Figure 1.

A-C. Preoperative CT (sagittal, axial, and coronal scans, respectively) showing a hyperdense lesion in the greater sphenoid wing extending into the left orbital cavity, middle cranial fossa, and temporal fossa accompanied by destruction and thickening of biparietal bones. D-F. Preoperative MRI (axial, sagittal, and coronal scans, respectively) showing three enhanced masses in anterior and middle cranial fossa and biparietal bones. G-I. Postoperative axial CT scan showing that the mass in the middle cranial fossa was residual, and frontal and temporal bones invaded by the tumor were resected.

The patient underwent a left trans-orbitotemporal craniotomy, and a moderately vascular tumor in the greater wing of sphenoid bone was resected. We found during the operation that the tumor had eroded the bone completely. Dissection was carried out until normal bone on all sides was exposed. A 1-cm bone margin was defined all around the tumor and the bone flap was removed. The infiltrating dura was widely excised. The left periorbital region, the dura mater of the middle cranial fossa and temporalis muscle in the temporal fossa were not intact. The dural defect was rectified with a pericranial graft. Roughly 90% gross resection was achieved as confirmed by the operative findings and postoperative imaging studies (Figure 1).

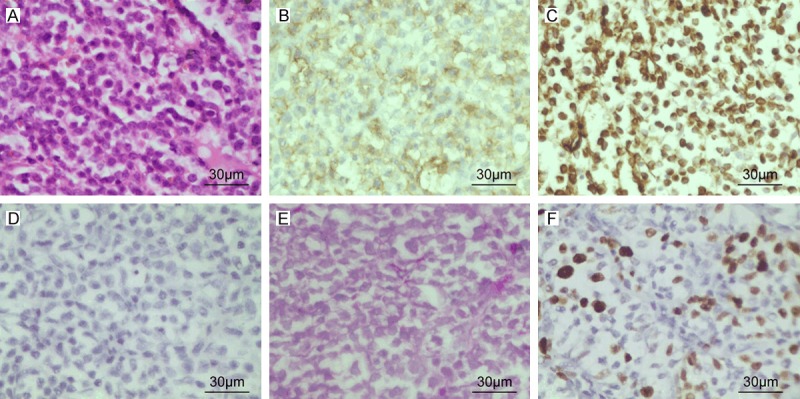

The pathological examination confirmed Ewing’s sarcoma. Histological analysis showed a malignant neoplasm composed predominantly of small-round cells with scanty cytoplasm and prominent nuclei. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor was positive for CD99 and vimentin, negative for neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, S-100, leukocyte common antigen (CD45), desmin, PAX5, CD10, CD3, CD20, MUM1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT). The Ki-67 labeling index was 40% (Figure 2). The patient’s vision in the left eye failed to improve even after tumor excision. The patient’s parents refused radiochemotherapy postoperatively. With an uneventful postoperative course, the patient was discharged on postoperative day 16 without any new neurologic deficits. At follow-up 1 month after hospital discharge, the patient showed unconsciousness and quadriplegia, and was dead 2 months after operation.

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor specimen showing densely packed, small round cells with scanty clear cytoplasm and regular vesicular and hyper chromatic nuclei (B-D). Immunohistochemical analyses showing positive membranous staining for CD99 (B), positive staining for Vimentin (C) and negative for neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (D). (E) Periodic acid Schiff staining of the tissue showing the presence of glycogen granules. (F) Immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67. The tumor exhibited 40% Ki-67 labeling index.

Discussion

Ewing’s sarcoma was first described by James Ewing as “endothelioma of the bone”. In 2002, The World Health Organization classified Ewing’s sarcoma with primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) as a single pathological entity [3]. Therefore, the term Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET family of tumors is currently employed. Ewing’s sarcoma, the second most common bone tumor in children, accounts for approximately 10% of primary malignant bone tumors. Of these cases, 90% occur in the first or second decade of life with a slight male predominance, with a ratio of 1.4:1. Most of the primary tumors occur in the long bones (47%), pelvis (19%), or ribs (12%) [1]. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma arising in the cerebral cranium (including frontal, temporal, occipital, parietal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones) is exceptionally rare, with only 71 cases involving intracranial extension reported in the English literature (Table 1) including 1 case with multiple lesions and 70 cases with single lesion. Among the cases associated with cranium, the temporal bone was involved in 20 cases, the frontal bone in 17 cases, the occipital bone in 13 cases, and the parietal bone in 13 cases. The cranium and cranial base account for approximately 70% and 30% of these cases, respectively. Shinsuke Sato et al in 2009 reported the first adult case of Ewing’s sarcoma with multiple primary cranial lesions [4]. Here we report a case of 5-year-old male patient with multiple primary Ewing’s sarcoma involving the cranial bones, which is the first reported pediatric case to date.

Table 1.

Seventy-one reported cases of primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the cerebral cranium

| NO. | References | Age/Sex | Tumor location | Therapy | Outcomes and follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fitzer & Steffey (1976) [11] | 9 y/F | Petrous | S | Not reported |

| 2 | Alvarez et al. (1979) [12] | 6 y/M | Orbital roof | S (×2) +RT+CT | Alive, NR, NM (7 m) |

| 3 | Hara et al. (1980) [13] | 5 y/F | Temporal | S (×2) +RT | Alive(3 y) |

| 4 | Mohan V et al. (1981) [13] | 10 y/M | Parieto-occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, metastasis (+) (2 y) |

| 5 | Mansfield (1982) [14] | 34 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (1 y) |

| 6 | Shigemitsu et al. (1985) [15] | 14 y/F | Orbital roof | S+RT+CT | Alive (1 y) |

| 7 | Haward & Lund (1985) [16] | 14 y/F | Ethmoid | S+RT+CT | Alive (1 y) |

| 8 | Jayaram G et al. (1986) [17] | 17 y/M | Parietal | RT | Alive (immediately) |

| 9 | Steinbok et al. (1986) [18] | 3 y/F | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (18 m) |

| 10 | Caroll & Miketic (1987) [19] | 4 y/F | Temporal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR, NM (3 y) |

| 11 | Woodruff et al. (1988) [20] | 6 y/M | Ethmoid | Bp+RT+CT | Alive, NR (9 m) |

| 12 | Freeman et al. (1988) [21] | 17 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (6 m) |

| 13 | Naidu (1989) [22] | NA/F | Frontal | S+RT | Alive, NR, NM (1 y) |

| 14 | Colak et al. (1991) [23] | 8 y/M | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive (9 m) |

| 15 | Colak et al. (1991) [23] | 8 y/F | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive (69 m) |

| 16 | Colak et al. (1991) [23] | 10 y/F | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive (16 m) |

| 17 | Davidson et al. (1991) [24] | 11 y/F | Temporal | Bp+RT+CT | Died due to recurrence (46 m) |

| BMT | |||||

| 18 | Roosen et al. (1991) [25] | 10 y/F | Frontoparietal | S+CT | Alive, NR, NM (2 y) |

| 19 | Hollody et al. (1992) [26] | 7 y/F | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, metastasis (+) (2 y) |

| 20 | Watanabe et al. (1992) [27] | 19 y/M | Temporal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR, NM (1 y) |

| 21 | Yildizhan et al. (1992) [28] | 13 y/F | Frontotemporal | S+CT | Alive (15 m) |

| 22 | Mishra et al. (1993) [29] | 16 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (3 y) |

| 23 | Mishra et al. (1993) [29] | 19 y/M | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (2.5 y) |

| 24 | Krishnan et al. (1993) [30] | 12 y/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Not reported |

| 25 | Majumdar et al. (1994) [31] | 6 y/F | Temporoparietal | Bp+RT+CT | Alive (2 y) |

| 26 | Zenke et al. (1994) [32] | 12 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive (18 m) |

| 27 | Tournut et al. (1994) [33] | 11 y/F | Occipital | S+ CT | Died due to metastasis (18 m) |

| 28 | Nakane et al. (1994) [34] | 32 y/F | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR, NM (2 y) |

| 29 | Hadfield et al. (1996) [35] | 1 y/F | Parietal | S+ CT | Died of sepsis, clinically free of tumor (9 m) |

| 30 | Kuzeyli et al. (1997) [36] | 10 y/F | Frontotemporal | S+RT+CT | Died of lung metastases (6 m) |

| 31 | Bhatoe et al. (1998) [37] | 27 y/M | Frontotemporal | S+RT+CT | Alive, recurrence (7 w) |

| 32 | Varan et al. (1998) [38] | 10 y/M | Sphenoid | S | Not reported |

| 33 | Carlos et al. (1999) [39] | 2 y/F | Frontal | S+CT | Alive (immediately) |

| 34 | Carlos et al. (1999) [39] | 5 m/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (8 y) |

| 35 | Sharma et al. (2000) [15] | 16 y/F | Sphenoid | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (1 m) |

| 36 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 1.6 y/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (27 m) |

| 37 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 10 y/M | Temporal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (26 m) |

| 38 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 18 y/F | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (3 y) |

| 39 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 40 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (8 m) |

| 40 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 9 y/F | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (8 y) |

| 41 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 6.6 y/M | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (86 m) |

| 42 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 18 y/F | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (74 m) |

| 43 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 19 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Not reported |

| 44 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 18 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (64 m) |

| 45 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 3 y/M | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (76 m) |

| 46 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 13 y/F | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive (2 y) |

| 47 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 17 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (74 m) |

| 48 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 14 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (26 m) |

| 49 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 20 y/F | Parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (80 m) |

| 50 | Desai et al. (2000) [1] | 18 m/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive (9 m) |

| 51 | Faith et al. (2001) [40] | 17 y/F | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR, NM (14 m) |

| 52 | Paramjeet et al. (2002) [41] | 4 y/M | Sphenoid | S+RT+CT | Not reported |

| 53 | Kostas et al. (2003) [42] | 22 y/M | Sphenoid | Bp+RT+CT | Free of symptoms (18 m) |

| 54 | Takasumi et al. (2003) [13] | 16 m/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Died of systemic metastasis (7 y) |

| 55 | Faiz et al. (2004) [43] | 2 y/M | Temporoparietal | S | Not reported |

| 56 | Ashwani et al. (2005) [44] | 5 y/M | Sphenoid | S+RT+CT | Not reported |

| 57 | Li et al. (2005) [45] | 9 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Alive, recurrence (32 m) |

| 58 | Li et al. (2005)[45] | 7 y/M | Occipital | S+ RT+CT | Alive, disease-free (3 y) |

| 59 | Pfeiffer et al. (2006) [46] | 5 m/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Developmentally normal (25 m) |

| 60 | Garg et al. (2007) [47] | 7 y/F | Occipital | S | Not reported |

| 61 | Srikant et al. (2008) [48] | 17 y/M | Petroclival | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (1 y) |

| 62 | Amit et al. (2009) [49] | 11 y/M | Frontal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (1 y) |

| 63 | Shinsuke et al. (2009) [4] | 25 y/M | Right parietal | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (1 y) |

| left frontal | |||||

| 64 | Stacey et al. (2009) [50] | 17 y/M | Ethmoid | S+RT+CT | Alive, NR (2 y) |

| 65 | Stacey et al. (2009) [50] | 15 y/F | Ethmoid | CT+S+RT | Alive, NR (3 y) |

| 66 | Kadar et al. (2010) [51] | 16 y/M | Petrous | S+RT+CT | Alive, NA (9 m) |

| 67 | Sumit et al. (2012) [52] | 29 y/M | Sphenoid sinus | S+RT+CT | Metastasis after 2 weeks, died after 3 weeks |

| sella, clivus | |||||

| 68 | Alok et al. (2012) [53] | 9 y/F | Frontal | S+CT | Not reported |

| 69 | Asifur et al. (2013) [54] | 18 y/M | Frontoparietal | S | Recurrence (1 m) |

| 70 | Fakbr et al. (2014) [55] | 1 m/M | Anterior fontanelle | S+CT | Died of recurrence (2 m) |

| 71 | Pravin et al. (2014) [56] | 52 y/M | Occipital | S+RT+CT | Died of recurrence (4.5 m) |

S = surgery. RT = radiation therapy. CT = chemotherapy. BP = biopsy. NR = no recurrence. NM = no metastasis.

In our literature review, the initial clinical features of primary Ewing’s sarcoma involving the cranial bones were generally atypical. Headache was the most common symptom and papilledema was the most common sign. Most patients with Ewing’s sarcoma of cranium presented with gradually increasing swelling. Most patients who were afflicted with Ewing’s sarcoma of the cranial bases presented with headaches and vomiting, which was symptomatic of increased intracranial pressure. The short average duration of symptoms (3 months) suggested rapid growth of the tumors, but most patients did not present obvious neurological deficits.

Ewing’s sarcoma is part of a large family of round-blue-cell tumors. It is composed of sheets of small cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The cytoplasm is scant, eosinophilic and usually contains glycogen, which is detected by periodic acid Schiff stain. The nuclei are round, with finely dispersed chromatin, and one or more tiny nucleoli. Occasional rosette formation is also seen. Immunohistochemical analysis of Ewing’s sarcomas reveals expression of vimentin and CD99, with characteristic perinuclear staining [5-7]. CD99 may also be expressed in lymphoblastic lymphoma and leukemia, but it is negative in neuroblastoma. Thus the differential diagnosis of intracranial small-round-cell-tumors should include neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma and leukemia. In our reported case, neuroblastoma was excluded in the diagnosis since neuron-specific enolase was negative and CD99 was positive. Lymphoblastic lymphoma and leukemia were excluded since leukocyte common antigen (CD45), CD3, CD20, and PAX5 were negative. Rhabdomyosarcoma was excluded since desmin was negative [6].

The resection of each tumor should be as radical as possible, to minimize tumor mass and reinforce the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy [8]. Whether there is any difference in outcomes between nearly total and total excision of Ewing’s sarcoma of the cranium is not known [9].

While the clinical, imaging, and pathological features of the current case are very similar to those of previous 71 reported cases, its poor prognosis and the multiple locations of lesions are different from those previously observed. Several reasons exist for the poor outcome. First, multiple masses lead to rapidly increasing intracranial pressure. Second, we failed to perform gross resection, as biparietal bony masses were not resected and a fraction of the mass that was located at the base of middle fossa was left behind. Third, the Ki-67 labeling index was 40%, and high Ki-67 index is often correlated with poor prognosis [10]. Fourth, the prognosis for patients with primary Ewing’s sarcomas of cranium is generally good when the tumors are treated with radical excision followed by radiotherapy and multidrug chemotherapy; however, the patient did not receive radiochemotherapy postoperatively.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Desai KI, Nadkarni TD, Goel A, Muzumdar DP, Naresh KN, Nair CN. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the cranium. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:62–68. discussion 68-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB Jr. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:425–430. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31816e22f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yip CM, Hsu SS, Chang NJ, Wang JS, Liao WC, Chen JY, Liu SH, Chen CH. Primary vaginal extraosseous Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor with cranial metastasis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:332–335. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato S, Mitsuyama T, Ishii A, Kawakami M, Kawamata T. Multiple primary cranial Ewing’s sarcoma in adulthood: case report. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:E384–386. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000337128.67045.70. discussion E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nascimento AG, Unii KK, Pritchard DJ, Cooper KL, Dahlin DC. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases of large-cell (atypical) Ewing’s sarcoma of bone. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai SS, Jambhekar NA. Pathology of Ewing’s sarcoma/PNET: Current opinion and emerging concepts. Indian J Orthop. 2010;44:363–368. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.69304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoury JD. Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12:212–220. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000175114.55541.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilepich MV, Vietti TJ, Nesbit ME, Tefft M, Kissane J, Burgert EO, Pritchard D. Radiotherapy and combination chemotherapy in advanced Ewing’s Sarcoma-Intergroup study. Cancer. 1981;47:1930–1936. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810415)47:8<1930::aid-cncr2820470803>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer CW Jr, Brickner TJ Jr, Perry RH. Ewing’s sarcoma: case against surgery. Cancer. 1967;20:1602–1606. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196710)20:10<1602::aid-cncr2820201006>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownhill S, Cohen D, Burchill S. Proliferation index: a continuous model to predict prognosis in patients with tumours of the Ewing’s sarcoma family. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzer PM, Steffey WR. Brain and bone scans in primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the petrous bone. J Neurosurg. 1976;44:608–612. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.44.5.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez-Berdecia A, Schut L, Bruce DA. Localized primary intracranial Ewing’s sarcoma of the orbital roof. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:811–813. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.6.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda T, Inagaki T, Yamanouchi Y, Kawamoto K, Kohdera U, Kawasaki H, Nakano T. A case of primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the occipital bone presenting with obstructive hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:792–799. doi: 10.1007/s00381-003-0816-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansfield JB. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull. Surg Neurol. 1982;18:286–288. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma RR, Netalkar A, Lad SD. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:53–56. doi: 10.1080/02688690042933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard DJ, Lund VJ. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the ethmoid bone. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99:1019–1023. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100098108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayaram G, Kapoor R, Saha MM. Ewing’s sarcoma: fine needle aspiration diagnosis of a tumor arising in the skull. Acta Cytol. 1986;30:553–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinbok P, Flodmark O, Norman MG, Chan KW, Fryer CJ. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the base of the skull. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:104–107. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198607000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll R, Miketic LM. Ewing sarcoma of the temporal bone: CT appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11:362–363. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198703000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodruff G, Thorner P, Skarf B. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the orbit presenting with visual loss. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:786–792. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.10.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman MP, Currie CM, Gray GF Jr, Kaye JJ. Ewing sarcoma of the skull with an unusual pattern of reactive sclerosis: MR characteristics. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1988;12:143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naidu MR. Primary Ewing’s tumor of the skull at birth. Indian J Pediatr. 1989;56:541–543. doi: 10.1007/BF02722439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colak A, Berker M, Ozcan OE, Erbengi A. CNS involvement in Ewing’s sarcoma. A report of 12 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;113:48–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01402114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson MJ. Ewing’s sarcoma of the temporal bone. A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:534–536. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90489-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roosen N, Lins E. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the calvarial skull. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1991;34:184–187. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollody K, Kardos M, Grexa E, Meszaros I. Ewing’s sarcoma in the occipital bone. Case report. Acta Paediatr Hung. 1992;32:371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe H, Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Koyama S, Nakamura S. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the temporal bone. Surg Neurol. 1992;37:54–58. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90067-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildizhan A, Gezen F. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull: follow-up with bone scanning. Neurosurg Rev. 1992;15:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00345940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra HB, Haran RP, Joseph T, Chandi SM. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull. A report of two cases. Br J Neurosurg. 1993;7:683–686. doi: 10.3109/02688699308995099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnan VV, Saraswathy A, Misra BK, Rout D. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the base of skull: a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1993;36:477–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majumdar J, Basu S, Dutta S, Roychowdhury J. Ewing’s sarcoma of temporoparietal region: a rare presentation. J Indian Med Assoc. 1994;92:202, 204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zenke K, Hatakeyama T, Hashimoto H, Sakaki S, Manabe K. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the occipital bone--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1994;34:246–250. doi: 10.2176/nmc.34.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tournut P, Turjman F, Laharotte JC, Froment JC, Gharbi S, Duquesnel J. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull presenting as an acute surgical emergency. Childs Nerv Syst. 1994;10:193–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00301090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakane T, Hashizume Y, Tachibana E, Mizutani N, Handa T, Mutsuga N, Yoshida J. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull base with intracerebral extension--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1994;34:628–630. doi: 10.2176/nmc.34.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadfield MG, Luo VY, Williams RL, Ward JD, Russo CP. Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull in an infant. A case report and review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;25:100–104. doi: 10.1159/000121104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuzeyli K, Akturk F, Reis A, Cakir E, Baykal S, Pekince A, Usul H, Soylev AE. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the temporal bone with intracranial, extracranial and intraorbital extension. Case report. Neurosurg Rev. 1997;20:132–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01138198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhatoe HS, Deshpande GU. Primary cranial Ewing’s sarcoma. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:165–169. doi: 10.1080/02688699845348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varan A, Caner H, Saglam S, Buyukpamukcu M. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the sphenoid bone: a rare presentation. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:311. doi: 10.1007/s002470050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlotti CG Jr, Drake JM, Hladky JP, Teshima I, Becker LE, Rutka JT. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull in children. Utility of molecular diagnostics, surgery and adjuvant therapies. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31:307–315. doi: 10.1159/000028881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erol FS, Ozveren MF, Ozercan IH, Topsakal C, Akdemir I. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the occipital bone--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2001;41:206–209. doi: 10.2176/nmc.41.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh P, Jain M, Singh DP, Kalra N, Khandelwal N, Suri S. MR findings of primary Ewing’s sarcoma of greater wing of sphenoid. Australas Radiol. 2002;46:409–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2002.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Apostolopoulos K, Ferekidis E. Extensive primary Ewing’s sarcoma in the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65:235–237. doi: 10.1159/000073123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmad FU, Suri A, Mahapatra AK, Ralte A, Sarkar C, Garg A. Giant calvarial Ewing’s sarcoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40:44–46. doi: 10.1159/000076579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma A, Garg A, Mishra NK, Gaikwad SB, Sharma MC, Gupta V, Suri A. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the sphenoid bone with unusual imaging features: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li WY, Brock P, Saunders DE. Imaging characteristics of primary cranial Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:612–618. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-1438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfeiffer J, Boedeker CC, Ridder GJ. Primary Ewing sarcoma of the petrous temporal bone: an exceptional cause of facial palsy and deafness in a nursling. Head Neck. 2006;28:955–959. doi: 10.1002/hed.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg A, Ahmad FU, Suri A, Mahapatra AK, Mehta VS, Atri S, Sharma MC, Garg A. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the occipital bone presenting as hydrocephalus and blindness. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43:170–173. doi: 10.1159/000098397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balasubramaniam S, Nadkarni T, Menon R, Goel A, Rajashekaran P. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the petroclival bone. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:712–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agrawal A, Dulani R, Mahadevan A, Vagaha SJ, Vagha J, Shankar SK. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the frontal bone with intracranial extension. J Cancer Res Ther. 2009;5:208–209. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.57129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gray ST, Chen YL, Lin DT. Efficacy of Proton Beam Therapy in the Treatment of Ewing’s Sarcoma of the Paranasal Sinuses and Anterior Skull Base. Skull Base. 2009;19:409–416. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadar AA, Hearst MJ, Collins MH, Mangano FT, Samy RN. Ewing’s Sarcoma of the Petrous Temporal Bone: Case Report and Literature Review. Skull Base. 2010;20:213–217. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thakar S, Furtado S, Ghosal N, Dilip J, Mahadevan A, Hegde A. Skull-base Ewing sarcoma with multifocal extracranial metastases. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:636–638. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.106584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Umredkar A, Gupta SK, Chhabra R, Das Radotra B. Primary calvarial Ewing’s sarcoma presenting as a giant fungating skull tumour: a case report. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:902–904. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.685782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman A, Bhandari PB, Hoque SU, Wakiluddin AN. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the skull. BMJ Case Rep. 2013:2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fakhouri FZ, Frasheh CN. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma of the anterior fontanelle in a neonate. Saudi Med J. 2014;35:739–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salunke P, Sharma M, Gupta K. Ewing sarcoma of the occipital bone in an elderly patient. World Neurosurg. 2014;81:e10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]