Abstract

Although Mexican Americans are the largest ethnic minority group in the nation, knowledge is limited regarding this population's adolescent romantic relationships. This study explored whether 12th grade Mexican Americans’ (N = 218; 54% female) romantic relationship characteristics, cultural values, and gender created unique latent classes and if so, whether they were linked to adjustment. Latent class analyses suggested three profiles including, relatively speaking, higher, satisfactory, and lower quality romantic relationships. Regression analyses indicated these profiles had distinct associations with adjustment. Specifically, adolescents with higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationships reported greater future family expectations, higher self-esteem, and fewer externalizing symptoms than those with lower quality romantic relationships. Similarly, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported greater academic self-efficacy and fewer sexual partners than those with lower quality romantic relationships. Overall, results suggested higher quality romantic relationships were most optimal for adjustment. Future research directions and implications are discussed.

Keywords: Mexican American, Romantic relationships, Adolescence, Latent class analysis, Adjustment

Adolescent romantic relationships are normative events that help prepare adolescents for successfully attaining intimacy in young adulthood (Connolly & McIsaac, 2009; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003. These relationships also are highly prevalent; using a nationally representative sample (Add Health, 1994), Carver, Joyner, and Udry (2003) found that 55% of adolescents between 12 and 18 reported having been in a romantic relationship during the past 18 months. Furthermore, 58% of 16 year olds in this study reported having had the same romantic partner across a one to two year time span, in comparison to 21% of adolescents younger than age 14, supporting arguments that as adolescents mature, their romantic relationships become more stable (Furman & Wehner, 1994). However, adolescent romantic relationship researchers rarely have considered the complexity of these relationships particularly among minority adolescents such as Mexican Americans.

To help improve understanding of the complexity and significance of adolescent romantic experiences on adjustment, Collins (2003) suggested a five feature framework (i.e., involvement, partner selection, content, quality, cognitive and emotional processes) that, along with context and individual differences, introduce variability into adolescents’ romantic experiences. The current study focused on one of these five features: quality (i.e., the degree to which adolescent romantic relationships are advantageous). The purposes of this study were to (a) explore whether unique romantic relationship profiles emerged from 12th grade Mexican American adolescents’ relationship characteristics (i.e., intimacy, satisfaction, monitoring, conflict, aggression), cultural values (i.e., familism values, traditional gender role values) and gender; and if so, (b) examine whether these profiles were distinctly associated with important domains of adolescents’ adjustment (i.e., future family expectations, self-esteem, academic self-efficacy, externalizing and internalizing symptoms, number of sexual partners). The current study defined adolescent adjustment as encompassing both positive and negative psychosocial outcomes.

The importance of studying Mexican American adolescents

Mexican Americans account for nearly two-thirds of U.S. Latinos, the largest ethnic minority group in the country (Motel & Patten, 2012). Although adolescent romantic relationship research has encompassed Latinos broadly (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, 2005), few researchers have examined Mexican American adolescents specifically. In fact, most researchers have either compared Mexican American adolescents to non-Mexican American adolescents using qualitative research designs and smaller samples (e.g., Adams & Williams, 2011; Millbrath, Ohlson, & Eyre, 2009) or combined Mexican Americans with other Latin Americans, ignoring cultural differences among subgroups, while focusing on either descriptive information (e.g., Carver et al., 2003) or risks associated with adolescent romantic relationships (e.g., dating violence; Yan, Howard, Beck, Shattuck, & Hallmark-Kerr, 2010). In contrast, the current study examined more in-depth information about Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships with a focus on normative characteristics.

Adolescent romantic relationships

Adolescent romantic relationships have been defined as continuous interactions that are mutually acknowledged (e.g., an adolescent likes a person and this person likes him/her), typically characterized by intense emotions often indicated by affectionate behaviors (e.g., kissing; see Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009 for a review). Research seeking to understand the influence of adolescent romantic relationships on adjustment has varied in complexity from a focus on involvement to various relationship characteristics. This section describes the diversity of research findings linking adolescent romantic relationships to adjustment, the potential importance of Mexican American cultural values to romantic relationships, and the value of examining these relationships from a person-centered analytic approach.

Adolescent romantic relationships and adjustment

Research suggests that romantic relationship involvement is associated with optimal adolescent adjustment. Researchers have found that, in comparison to adolescents without romantic partners, those with romantic partners reported lower social anxiety, a relationship that was found primarily for Latinos (La Greca & Harrison, 2005). Also, adolescents with higher levels of dating experience (i.e., dating someone more than two months) reported higher perceptions of social acceptance, romantic appeal, and physical appearance than adolescents with lower levels of dating experience (Zimmer-Gembeck, Sibenbruner, & Collins, 2001). Similarly, adolescents who were in romantic relationships and were in love, reported being in better moods, having higher levels of concentration (Bajoghli, Joshanghani, Mohammadi, Holsboer-Trachsler, & Brand., 2011; Bajoghli et al., 2013), and being less tired throughout the day (Bajoghli et al., 2013). Moreover, adolescents engaged in serious romantic relationships (i.e., participated in multiple dating activities such as exchanging gifts, meeting their partner's parents) reported greater marital expectations than those not engaged in such serious relationships (Crissey, 2005). Researchers also have reported negative effects from adolescent romantic relationship involvement. For instance, in comparison to adolescents without romantic partners, those with romantic partners reported lower academic performance (for girls only; Brendgen, Vitaro, Doyle, Markiewicz, & Bukowski, 2002), greater externalizing symptoms (Hou et al., 2013), and greater depressive symptoms (Hou et al., 2013; Vujeva & Furman, 2011). Similarly, researchers found that adolescents engaged in steady romantic relationships before age 16 reported having more sexual partners at age 19 than those not engaged in steady relationships before age 16 (after controlling for gender; Zimmer-Gembeck & Collins, 2008). Because of these conflicting findings, it is unclear whether simply having a romantic partner in adolescence is healthy or not.

Thus, many researchers have moved from simply examining romantic relationship involvement to studying the influence of romantic relationship characteristics on adjustment. For example, romantic relationships characterized by satisfaction, closeness, and ease of sharing with romantic partner have been positively associated with several adolescent psychosocial factors (i.e., social acceptance, romantic appeal, global self-worth), but not with mental health and academic outcomes (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2001). Similarly, researchers found a positive association between companionate love (characterized by acceptance, trust, being unafraid of becoming too close, and few emotional extremes) and self-esteem for girls, but not for boys (Bucx & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010). Moreover, relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with depressive symptoms and negative emotions (e.g., sad/withdrawn) both concurrently and two years later for girls, but not for boys (Ha, Dishion, Overbeek, Burk, & Engels, 2013). Similarly, negative romantic relationship characteristics have been associated with less optimal adjustment. For example, negative romantic partner interactions were associated with higher social anxiety (for Latinos only) and depressive symptoms (stronger for European Americans than Latinos; La Greca & Harrison, 2005). Similarly, psychological aggression within a romantic relationship was linked to greater depressive symptoms, whereas physical aggression was not (Jouriles, Garrido, Rosenfield, & McDonald, 2009). To further advance adolescent romantic relationship research, the current study explored whether Mexican American adolescents’ positive and negative romantic relationship characteristics generated unique patterns that would be distinctly associated with adolescents’ adjustment in various domains.

Mexican American adolescents’ cultural values

Culture refers to a specific population's beliefs, practices, and traditions (Rogoff, 2003). Two cultural values commonly studied with Mexican Americans are familism and traditional gender role values. Familism reflects the importance of family and is commonly characterized by feelings of support and obligation (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Traditional gender role values are defined by beliefs that women are primarily responsible for child rearing and managing household chores, and are more submissive, whereas men are responsible for making household decisions, being the sole provider, and are thought of as more powerful (Knight et al., 2010). These cultural values have been linked with Mexican American adolescents’ adjustment; familism values have been associated with both better mental health (Fuligni & Pederson, 2002) and academic outcomes (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999; Author Citation) whereas traditional gender role values have been associated with lower educational expectations and greater risky behaviors for boys, but less risky behaviors for girls (Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, Wheeler, & Perez-Brena, 2012).

Although scholars have asserted that cultural influences are important with respect to adolescent romantic relationships (e.g., Collins et al., 2009; Connolly & McIsaac, 2009), only two researchers have specifically examined the associations between Mexican American adolescents’ cultural values and their romantic relationships. A qualitative study by Millbrath et al. (2009) found that Mexican American adolescents scored higher than their African American peers on both cultural mores (i.e., expressions of traditional cultural values [e.g., importance of family]) and romantic care (i.e., expressions of healthy romantic relationship characteristics [e.g., commitment]). Moreover, Tyrell, Wheeler, Gonzales, Dumka, and Millsap (2014) quantitatively examined a sample of Mexican American adolescents and found a positive association between seventh graders’ familism values and their ninth grade romantic relationship intimacy. Together, these findings suggested that Mexican American adolescents with higher traditional cultural values such as familism may have healthier romantic relationships. To build upon this literature, the current study examined associations between Mexican American adolescent cultural values and romantic relationship characteristics using a person-centered approach.

Romantic relationship profiles

The current study used romantic relationship characteristics, cultural values, and gender to explore whether these observed variables generated unique latent classes, what often is called a person-centered approach (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). In comparison to a variable-centered approach where the focus is on associations among the variables, a person-centered approach takes unobserved heterogeneity of a population into account by categorizing homogenous subtypes of people within this population into classes and focusing on the meaning or importance of differences in these classes (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). A person-centered approach to studying adolescent romantic relationships may better illustrate the complexity of these relationships and, if unique classes (i.e., profiles) do exist, researchers can examine whether they are distinctly associated with adjustment. Because gender differences have been found in both romantic relationship characteristics (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003) and Mexican American adolescents’ cultural values (e.g., Updegraff et al., 2012), gender was included as a latent class indicator.

The current study

This study's first goal was to examine whether unique profiles emerged from 12th grade Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationship characteristics (both positive and negative), cultural values, and gender by using Latent Class Analysis (LCA). Given this exploratory approach, no hypotheses were made about the number of profiles that would emerge. The second goal was to examine whether these romantic relationship profiles were distinctly associated with adolescents’ adjustment. It is important to note that the current study focused on adolescent adjustment variables that have been found to be associated with adolescent romantic relationship involvement or characteristics in previous research (e.g., marriage expectations (Crissey, 2005), self-esteem (Bucx & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010), academics (Brendgen et al., 2002), mental health (Ha et al., 2013), number of sexual partners (Zimmer-Gembeck & Collins, 2008)).

Method

Participants

Data for this study came from a longitudinal investigation of the impact of culture and context on the adaptation of 749 Mexican American families from a Southwestern metropolitan area (Author Citation). We used data from the fourth wave (T4; 12th grade) of data collection and only from the 218 adolescents (M age = 17.86; SD = 0.45) who had a romantic relationship and reported information about their current romantic partner; this was 35% of the T4 sample. Fifty-four percent of these adolescents were female, 98% completed the interview in English, and 74% were born in the United States. The majority (71%) lived in two-parent households with a median family income between $30,001 and $35,000.

With respect to the overall sample, the retention rate from T1 (N = 749) to T4 was 84%. Attrition analyses indicated only one significant difference in participation at T4 by demographic characteristics; males were less likely to participate at T4 than females, χ2 (1) = 9.03, p < .01. Differences in participation at T4 did not emerge in adolescent nativity, household structure, interview language, or median family income. Moreover, there were no differences in T4 participation on the study variables that were examined at T1 (i.e., familism, traditional gender role values, academic self-efficacy, internalizing and externalizing symptoms).

Procedure

Complete procedures, as approved by the institutional review board, are described elsewhere (Author Citation). Purposive and random sampling techniques were used to identify 47 schools (i.e., public, charter, religious) in a large metropolitan area to recruit the most diverse sample possible. At each school, recruitment packets were sent home with every fifth-grader; 86% were completed and returned. Interested families were screened for eligibility (i.e., child attended the school; mother and child agreed to participate; mothers and fathers were the child's biological parents; the mother, father, and child were of Mexican descent; and the child was not severely learning disabled).

Data for the current study were collected from two cohorts of adolescents in 2011–2013 using computer assisted personal interviews which occurred at either participants’ home or over the telephone (only for those out of state). Each participating family member was given $60 as an incentive. Parents and adolescents were interviewed out of hearing range of each other and interviews lasted an average of 2.5 h. Interviewers read each question and response option aloud to control for variations in literacy.

Measures

Family demographics

Parents provided information on family annual household income; adolescents reported their age, language preference, and nativity.

Romantic relationship intimacy

Adolescents rated intimacy with their romantic partner using seven items (α = .85) adapted from Blythe and colleagues (Blyth & Foster-Clark, 1987; Blyth, Hill, & Thiel, 1982). This scale assessed acceptance, understanding, sharing feelings, and advice seeking (e.g., “How much do you share your inner feelings or secrets with name of partner?”). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater intimacy. This scale has been found reliable and valid for Mexican American adolescents (e.g., Davidson, Updegraff, & McHale, 2011 ).

Romantic relationship satisfaction

Adolescents rated satisfaction with their romantic partner using six items (α = .72) from the Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, 1988; e.g., “In general, how happy are you with your relationship?”). Participants responded to items one and four with answers ranging from 1 = all of the time to 5 = never; two with an answer ranging from 1 = very happy to 5 = very unhappy; items three and five with answers ranging from 1 = much better to 5 = much worse; and item six with an answer ranging from 1 = very much to 5 = not at all. Items one, two, three, five, and six were reverse coded; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater satisfaction.

Romantic relationship monitoring

Adolescents rated the monitoring of their romantic partner using five items (α = .83; e.g., “How much does name of partner know about where you go at night?”) adapted from the parental monitoring scale (Small & Kerns, 1993) with responses ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = everything; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater monitoring.

Romantic relationship conflict

Adolescents rated conflict with their romantic partner using the conflict subscale (five items [α = .88]; e.g., “How much do you and name of partner get upset or mad at each other?”) of the Network Relationship Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater conflict. This scale has been found reliable and valid for Mexican American adolescents (e.g., Thayer, Updegraff, & Delgado, 2008).

Romantic relationship aggression

Adolescents rated aggression in their romantic relationship using six items (α = .77) adapted from The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). This scale assessed psychological and physical aggression (e.g., How much do you and name of partner get angry and shout at each other?”). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater aggression. This scale has been found reliable and valid for Mexican Americans (e.g., Straus, 2004).

Cultural values

Adolescents rated their cultural values with the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS; Knight et al., 2010). Sixteen items (α = .86) assessed familism by dimensions of support and emotional closeness, family obligations, and the family as referent. Five items (α = .75; e.g., “It is important for the man to have more power in the family than the woman.”) assessed traditional gender role values. Responses for both familism and traditional gender role values ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = completely; for each value, mean scores were computed with higher scores representing greater values.

Future family expectations

Adolescents reported their expectations about having a family in the future using three items (α = .76; e.g., “How sure are you that you will get married?”) from the future expectations scale (Wyman, Cowen, Work, & Kerley, 1993). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all sure to 5 = very much sure; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater expectations.

Self-esteem

Adolescents reported their self-esteem using Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1979). This measure was comprised of ten items (α = .85; e.g., “I am able to do things as well as most other people.”) with responses ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; a mean score was computed with higher scores represented greater self-esteem. This scale has been found reliable and valid for Mexican American adolescents (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009).

Academic self-efficacy

Adolescents reported their academic self-efficacy using six items (α = .87; e.g., “You can do even the hardest schoolwork if you try”) from the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (Arunkumar, Midgley, & Urdan, 1999; Midgley, Maehr, & Urdan, 1996). Responses ranged from 1 = not at all true to 5 = very true; a mean score was computed with higher scores representing greater academic self-efficacy. This scale has been found to be reliable and valid with Mexican American adolescents (Gonzales et al., 2008).

Externalizing and internalizing symptoms

Mothers and adolescents independently reported on adolescent mental health using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Externalizing symptoms were computed by summing the conduct, attention deficit/hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorders symptom counts. Internalizing symptoms were computed by summing the anxiety and mood disorders symptom counts. A combined mother and adolescent scoring algorithm was used to obtain symptom counts because previous work suggested that the combined algorithm is a better choice than any single-informant algorithm (Shaffer et al., 2000). This measure is reliable and valid for English and Spanish speaking populations (Bravo, Woodbury-Fariña, Canino, & Rubio-Stipec, 1993).

Number of sexual partners

Adolescents reported the number of sexual partners they had within the past year (“In the past 12 months, how many different sexual partners have you had?”).

Results

Romantic relationship profiles

To attain the first goal of this study, a series of five LCAs were computed in Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2013). Analyses proceeded in a series of steps whereby a one-class solution was initially modeled with the number of classes increased by one thereafter. The best-fitting solution was determined by the interpretability of the solution, class sample size, the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), the sample size-adjusted BIC (aBIC; Sclove,1987), and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001). A model with lower BIC and aBIC values fits better than a model with higher BIC and aBIC values (Lubke & Muthén, 2005) and an LMR test with a p value less than 0.05 suggests that the model with k classes fits better than the k – 1 class model (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2012). To avoid local maxima and to ensure that the best loglikelihood values were replicated, analyses were computed in a stepwise fashion as recommended by Asparouhov and Muthén (2012). Once the best-fitting solution was determined, adolescents were assigned their most likely latent class membership representing their romantic relationship profile. Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) using the expectation–maximization algorithm (Enders, 2010).

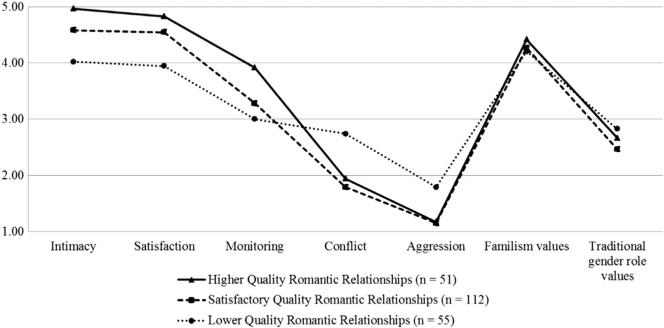

An assumption of LCA is that associations between the observed indicators are explained by the latent classes (i.e., local independence; Collins & Lanza, 2010), thus observed indicators were not allowed to correlate within classes; variances and means were allowed to be free across latent classes. Fit statistics and LMR results for the series of LCAs suggested that the three-class solution was the most optimal (Table 1). Indicator means and standard deviations for the sample and three-class solution are presented in Table 2. Wald tests were computed to examine whether indicator means were significantly different from one another between profiles where p less than 0.05 indicated a significant difference. Indicator means for the three-class solution are plotted in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Latent class analyses model fit statistics.

| BIC | aBIC | p LMR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-class solution | 2982.68 | 2935.15 | – |

| Two-class solution | 2624.44 | 2526.20 | <0.001 |

| Three-class solution | 2508.93 | 2359.99 | <0.01 |

| Four-class solution | 2535.52 | 2335.87 | >0.05 |

| Five-class solutiona | – | – | – |

Note. N = 218.

This model did not converge to proper solution so fit statistics are not provided. Bolded text indicates best-fitting solution. aBIC = Adjusted Bayesian information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for sample and romantic relationship profiles.

| Total sample (N = 218) |

Profiles |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Min.–Max. | Higher Quality Romantic relationships M (n = 51) | Satisfactory Quality Romantic relationships M (n = 112) | Lower Quality Romantic relationships M (n = 55) | |

| Romantic relationship characteristics | |||||

| Intimacy | 4.52 (0.51) | 2.71–5.00 | 4.97a | 4.58b | 4.02c |

| Satisfaction | 4.45 (0.53) | 1.67–5.00 | 4.83a | 4.55b | 3.94c |

| Monitoring | 3.35 (0.63) | 1.20–5.00 | 3.92a | 3.28b | 3.00c |

| Conflict | 2.06 (0.75) | 1.00–4.40 | 1.94a | 1.79a | 2.74b |

| Aggression | 1.32 (0.44) | 1.00–3.33 | 1.17a | 1.15a | 1.79b |

| Cultural values | |||||

| Familism | 4.29 (0.46) | 2.94–5.00 | 4.42a | 4.27ab | 4.20b |

| Traditional gender roles | 2.61 (0.84) | 1.00–4.80 | 2.67ab | 2.47b | 2.83a |

| % Male adolescents | 46% | – | 46%a | 43%b | 53%c |

Note. Means that do not share superscripts are significantly different from one another where p < .05.

Fig. 1.

Mexican American adolescent romantic relationship latent profile means (N = 218). Note. Higher means represents greater levels, whereas lower means represents lower levels.

A little less than a quarter of the sample (23.4%) was included in the first latent class. In comparison to the overall sample, these adolescents reported (a) above average intimacy, satisfaction, monitoring, and familism values; (b) average conflict and traditional gender role values; and (c) below average aggression. This profile was categorized as higher quality romantic relationships. A little more than half of the total sample (51.4%) was included in the second latent class. In comparison to the overall sample, these adolescents reported (a) average intimacy, satisfaction, monitoring, familism values, and traditional gender role values and (b) below average conflict and aggression. This profile was categorized as satisfactory quality romantic relationships. Finally, about a quarter of the total sample (25.2%) was included in the third latent class. In comparison to the overall sample, these adolescents reported (a) above average conflict, aggression, and traditional gender role values; (b) average familism values; and (c) below average intimacy, satisfaction, and monitoring. This profile was categorized as lower quality romantic relationships. Moreover, being male decreased adolescents’ odds of being classified in both the higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationship profiles than in the lower quality romantic relationship profile by 26% (odds ratio [OR] = 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI; 0.30, 1.85], p < .05) and 33% (OR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.32, 1.44], p < .05), respectively. In contrast, being male increased adolescents’ odds of being classified in the higher quality romantic relationship profile than in the satisfactory quality romantic relationship profile by 10% (OR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.46, 2.66], p < .05).

Romantic relationship profiles and adjustment

To attain the second goal of this study, the associations between profiles and adjustment variables were examined. Using Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2013), future family expectations, self-esteem, academic self-efficacy, externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and number of sexual partners were simultaneously regressed on adolescents’ most likely latent class as if it were an observed variable. Treating latent classes as observed is appropriate provided entropy is greater than 0.80 (Clark & Muthén, 2010); entropy for the three-class solution was 0.86. Most adjustment variables had complete data, but future family expectations (13% missing), academic self-efficacy (12% missing), and number of sexual partners (30% missing) did not. Descriptive statistics for study variables are presented in Table 3 and simultaneous regression results are presented in Table 4. In Model 1, lower quality romantic relationships was used as the reference group and in Model 2, satisfactory quality romantic relationships was used as the reference group. Results indicated that adolescents with higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationships reported greater future family expectations, higher self-esteem, and fewer externalizing symptoms than those with lower quality romantic relationships. Similarly, adolescents with higher, but not those with satisfactory quality romantic relationships reported greater academic self-efficacy and fewer sexual partners than those with lower quality romantic relationships (Table 4, Model 1). Moreover, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported greater future family expectations and higher academic self-efficacy than those with satisfactory quality romantic relationships (Table 4, Model 2).

Table 3.

Zero-order correlations, means, and standard deviations for romantic relationship characteristics, cultural values, and adjustment variables (N = 218).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intimacy | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Satisfaction | 0.72 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3. Monitoring | 0.46 | 0.35 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4. Conflict | –0.14 | –0.13 | –0.01 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5. Aggression | –0.19* | –0.20 | –0.03 | 0.67 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. Familism | 0.16* | 0.16* | 0.00 | –0.04 | –0.07 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7. Traditional | –0.05 | –0.02 | –0.08 | 0.12 | 0.17** | 0.34 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8. Future fam. | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.18** | –0.13 | –0.19* | 0.11 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9. Self-esteem | 0.27 | 0.22** | 0.02 | –0.26 | –0.17** | 0.13 | –0.07 | 0.32 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10. Ac. self-efficacy | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.14* | –0.17* | –0.07 | 0.14 | –0.11 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |||

| 11. Externalizing | –0.20 | –0.15** | –0.03 | 0.18* | 0.15** | –0.23 | –0.02 | –0.22** | –0.29 | –0.16* | 1.00 | ||

| 12. Internalizing | –0.06 | –0.01 | –0.05 | 0.13 | 0.09 | –0.04 | –0.04 | –0.22** | –0.28 | –0.12 | 0.51 | 1.00 | |

| 13. Sexual partners | –0.24** | –0.19 | –0.24 | –0.02 | 0.03 | –0.02 | 0.20** | –0.10 | –0.09 | –0.11 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 1.00 |

| 14. Gender | –0.08 | –0.04 | –0.08 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.16* | 0.07 | 0.02 | –0.28 | 0.22 |

| M | 4.52 | 4.45 | 3.35 | 2.06 | 1.32 | 4.29 | 2.61 | 4.14 | 3.33 | 4.36 | 3.81 | 10.56 | 1.77 |

| SD | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 2.30 | 3.30 | 7.96 | 0.59 |

Note. Sample size ranged from 152 to 218 for variables; missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood. Gender was coded 0 = female, 1 = male. Ac. self-efficacy = Academic self-efficacy; Future fam. = Future family expectations; Traditional = Traditional gender roles.

p < .05.

p < .01. Boldface p < .001.

Table 4.

Regression analyses for associations between romantic relationship profiles and adjustment variables (N = 218).

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β (SE) | B (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Future family expectations | ||||

| Higher quality RR | 0.84 (0.16) | 1.00 (0.17) | 0.32 (0.13)* | 0.38 (0.15)* |

| Satisfactory quality RR | 0.52 (0.14) | 0.61 (0.16) | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ||

| Self-esteem | ||||

| Higher quality RR | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.17) |

| Satisfactory quality RR | 0.24 (0.07)** | 0.54 (0.15) | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| Academic self-efficacy | ||||

| Higher quality RR | 0.37 (0.11)** | 0.63 (0.18) | 0.22 (0.09)* | 0.37 (0.15)* |

| Satisfactory quality RR | 0.15 (0.11) | 0.25 (0.18) | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| Externalizing symptoms | ||||

| Higher quality RR | –1.53 (0.61)* | –0.46 (0.18)* | –0.34 (0.52) | –0.10 (0.15) |

| Satisfactory quality RR | –1.18 (0.55)* | –0.36 (0.17)* | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| Internalizing symptoms | ||||

| Higher quality RR | –1.97 (1.50) | –0.25 (0.19) | –1.14 (1.24) | –0.14 (0.15) |

| Satisfactory quality RR | –0.83 (1.37) | –0.11 (0.17) | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Number of sexual partners | ||||

| Higher quality RR | –1.16 (0.57)* | –0.51 (0.18)** | –0.16 (0.29) | –0.07 (0.12) |

| Satisfactory quality RR | –1.01 (0.57) | –0.44 (0.20) | ||

| Lower quality RR | ||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

Note. In Model 1, Lower quality RR is the reference group. In Model 2, Satisfactory quality RR is the reference group. RR = Romantic relationships.

p < .05.

p < .01. Boldface p < .001.

Discussion

This study employed a person-centered analytic technique at a developmental period when adolescent romantic relationships are relatively more stable (Furman & Wehner, 1994) to better understand the overall quality of these relationships among 12th grade Mexican Americans. Specifically, we explored whether relationship characteristics, cultural values, and gender created unique latent classes and, if so, whether they were distinctly associated with adolescents’ adjustment in various domains. Three unique romantic relationship profiles emerged and had distinct associations with adjustment. Overall, results suggested that most adolescents had healthy romantic relationships.

Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationship profiles

The majority of these Mexican American adolescents (75%) had satisfactory and higher quality relationships characterized by average or above average levels of intimacy, satisfaction, and monitoring paired with average or below average levels of conflict and aggression. In contrast, few adolescents (25%) had lower quality romantic relationships characterized by below average levels of intimacy, satisfaction, and monitoring paired with above average levels of conflict and aggression. This was the first study to find that monitoring was associated with healthier romantic relationships. Prior findings suggested romantic partner monitoring might be a negative characteristic because it was linked to other negative relationship characteristics (i.e., jealousy, insecure attachment styles; e.g., Fox & Warber, 2014; Muise, Christofides, & Desmarais, 2013). We used a broader monitoring measure that was not related to a specific context (i.e., electronic monitoring) which may be one reason for these contrasting findings. Overall, these profiles provided evidence of significant within-group variations for Mexican American adolescents’ positive and negative romantic relationship characteristics.

Some of the profiles were also distinct with respect to cultural values and gender which may provide some insight regarding the differences in relationship characteristics among profiles. Specifically, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported higher intimacy, satisfaction, monitoring, and familism values and lower conflict and aggression than adolescents with lower quality romantic relationships. Williams and Hickle (2011) found that Mexican American adolescents valued relationship commitment more than non-Mexican Americans, something they posited to be associated with familism values. Similarly, Millbrath et al. (2009) suggested that Mexican American adolescents’ cultural values may be associated with experiencing healthy romantic relationships. Finally, Tyrell et al. (2014) found that Mexican American adolescents’ familism values were positively associated with their romantic relationship intimacy. For these reasons, adolescents with higher familism values (i.e., those with higher quality relationships) may have a stronger desire to have a family of their own someday and therefore place greater importance on engaging in healthy romantic relationships than adolescents with lower familism values (i.e., those with lower quality romantic relationships). Moreover, adolescents with lower quality romantic relationships reported lower intimacy, satisfaction, and monitoring, but higher conflict, aggression, and traditional gender role values than adolescents with satisfactory quality romantic relationships. Notably, those with lower quality relationships were more likely to be male. This pattern is aligned with research which has found that adolescent boys reported lower levels of intimacy (Tyrell et al., 2014), lower levels of romantic partner social support (Seiffge-Krenke, 2003), higher negative relationship qualities (e.g., conflict; La Greca & Harrison, 2005), and higher traditional gender role values (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Baezconde-Garbanai, Ritt-Olson, & Soto, 2012) than adolescent girls. Overall, the differences in relationship characteristics, cultural values, and gender among the three profiles provided evidence of important within-group variations in Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships. More important, within adolescents’ current romantic relationship contexts, higher familism values appeared to be a resource given they were a distinguishing cultural characteristic between higher and lower quality romantic relationships.

Romantic relationship profiles and adjustment

We also examined whether the unique romantic relationship profiles were distinctly associated with adolescents’ adjustment; higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationships were associated with optimal outcomes whereas lower quality romantic relationships were not. Similar to previous findings (Crissey, 2005), adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported greater future family expectations than adolescents with satisfactory and lower quality romantic relationships. Because adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported the highest positive relationship characteristics, familism values, and future family expectations, one can speculate that they may become married and have children earlier than adolescents with satisfactory and lower quality romantic relationships. Adolescents with both higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationships reported higher self-esteem than those with lower quality romantic relationships (e.g., Bucx & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010). Moreover, previous studies indicated that adolescent romantic relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (for girls only; Ha et al., 2013) and negative romantic partner interactions were positively associated with depressive symptoms (an association that was stronger for European Americans than Latinos; La Greca & Harrison, 2005), but the current study found no differences in internalizing symptoms among the three profiles. In comparison to prior studies, the current approach to examining associations between adolescents’ romantic relationships and their adjustment was multidimensional and person-centered versus simpler and variable-centered which may be one reason for the contrasting findings.

Previous studies indicated that romantic relationship involvement was associated with lower academic performance (for girls only; Brendgen et al., 2002), greater externalizing symptoms (Hou et al., 2013), and more sexual partners (for those who had a serious relationship before age 16; Zimmer-Gembeck & Collins, 2008); however, the current study's results illustrated that these associations may be more complex further supporting the need for researchers to use person-centered analytic techniques. For example, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported greater academic self-efficacy than those with both satisfactory and lower quality romantic relationships. Thus, it seems as though it is the overall quality of the romantic relationship that is associated with adolescents’ academic outcomes instead of whether simply one is romantically involved. Also important, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported the highest familism values which is aligned with research that has positively linked Mexican American adolescents’ familism values to their academic adjustment (e.g., Fuligni et al., 1999; Author Citation). Moreover, adolescents with both higher and satisfactory quality romantic relationships reported fewer externalizing symptoms than those with lower quality romantic relationships demonstrating that healthier relationships were negatively associated with externalizing symptoms. Finally, adolescents with higher quality romantic relationships reported fewer sexual partners than those with lower quality romantic relationships. Because adolescent familism values were a distinguishing cultural characteristic between these two profiles, perhaps adolescents who were more family oriented placed greater importance on having one romantic partner instead of several. In support of this, Williams and Adams (2013) found that Mexican American adolescents discussed relationships characterized by higher levels of commitment and investment than their European American peers. Overall, the current study's results underscore the need for researchers to focus on romantic relationship quality than on simply relationship involvement. As the current study's results illustrated, romantic relationship quality may not be adequately represented by single indicators.

Implications and future directions

Although prior research generally indicated that positive romantic relationship characteristics were associated with optimal adjustment whereas negative characteristics were not, these efforts focused on one characteristic at a time and did not consider whether multivariate patterns of romantic relationships existed and if they were associated with adolescents’ adjustment. With a diverse sample of Mexican American adolescents, we identified three unique romantic relationship profiles that were distinctly associated with adolescent adjustment in various domains. Although we used a person-centered analytic technique to build upon the current literature, there is still room for expansion. For example, it may be important to understand if there is a specific period of time during adolescence when an overall higher quality romantic relationship may be most optimal for adjustment. That is, are higher quality romantic relationships always optimal for adjustment or only during later adolescence as with the current sample? It may also be important for researchers to consider whether changes in Mexican American adolescents' cultural values during adolescence influence the overall quality of their romantic relationships later on. Specifically, would changes in adolescents’ acculturation or biculturalism across time be distinctly associated with the quality of their romantic relationships in adolescence and beyond? With respect to prevention, researchers should seek to better understand predictors of these profiles; in particular, classification into lower quality romantic relationships may be most critical given these adolescents (who are more likely to be male) were at greatest risk for experiencing externalizing symptoms. For instance, researchers might want to consider how risk contexts in early adolescence (Zeiders, Roosa, Knight, & Gonzales, 2013) may directly and/or indirectly predict romantic relationships in later adolescence. Given the differentiation by adolescent familism values between higher and lower quality romantic relationships, encouraging Mexican American families to bolster/maintain their familism values may be a mode of intervention. Overall, the findings provide ideas for future research as well as guidance for developing culturally appropriate interventions.

Limitations, strengths, and summary

Although the current study employed an innovative analytic technique to explore whether unique patterns of Mexican American adolescent romantic relationships emerged, one must consider that these profiles and their distinct associations with adolescents’ adjustment in various domains were relative to one another and might be unique to the current sample. For instance, lower quality romantic relationships were characterized by low intimacy, satisfaction, and monitoring as well as high conflict and aggression where “low” and “high” were determined relative to the rest of the current sample. Thus, this study's findings need to be replicated. Moreover, the associations between romantic relationship profiles and adolescent adjustment variables were examined cross-sectionally thus there was no way to determine whether adolescents who were well-adjusted selected into healthier romantic relationships or if adolescents with healthier romantic relationships became well-adjusted. Similarly, profiles depicted adolescents’ romantic relationships with their current romantic partner and it was unknown whether adolescents would be classified into the same profile with a different partner.

Despite these limitations, the study had several strengths. Instead of comparing Mexican Americans adolescents to non-Mexican American adolescents, the current study examined within-group variations of romantic relationship quality. Moreover, as opposed to providing solely descriptions of relationships or exclusively focusing on risks, the current study used a person-centered analytic technique to examine both positive and negative romantic relationship characteristics, cultural values, and gender to determine whether unique romantic relationship profiles emerged. Overall, this study significantly contributed to adolescent romantic relationship research by (a) providing evidence of within-group variations among 12th grade Mexican American romantic relationships without solely focusing on risks of these relationships, (b) using a more diverse sample of than is common in research on Mexican Americans (Author Citation); (c) using a more robust analytic approach than has been used in previous research to better understand the complex associations between adolescents’ romantic relationships and their cultural values, and (d) being able to make empirical inferences with respect to the overall quality (e.g., Collins, 2003) of Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported, in part, by grant MH 68920 (Culture, context, and Mexican American mental health) and the Cowden Fellowship program of the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. The National Institute of Health is not responsible for the content of this paper. The authors are thankful for the support of F. Scott Christopher, Nancy Gonzales, George Knight, Roger E. Millsap, Jenn-Yun Tein, Jaimee Virgo, Rebecca M. B. White, the Community Advisory Board, interviewers, and families who participated in the study.

References

- Adams HL, Williams LR. What they wish they would have known: support for comprehensive sexual education for Mexican American and White adolescents' dating and sexual desires. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1875–1885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.013. [Google Scholar]

- Add Health About Add Health. 1994 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/about.

- Arunkumar R, Midgley C, Urdan T. Perceiving high or low home-school dissonance: longitudinal effects on adolescent emotional and academic well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:441–466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0904_4. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Using Mplus TECH11 and TECH14 to test the number of latent classes. 2012 Mplus Web Notes: No. 14. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote14.pdf.

- Bajoghli H, Joshanghani N, Gerber M, Mohammadi MR, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S. In Iranian female and male adolescents, romantic love is related to hypomania and low depressive symptoms, but also to higher state anxiety. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2013;17:98–109. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2012.697564. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2012.697564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajoghli H, Joshanghani N, Mohammadi MR, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S. In female adolescents, romantic love is related to hypomanic-like stages and increased physical activity, but not to sleep or depressive symptoms. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2011;15:164–170. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2010.549340. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2010.549340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Foster-Clark FS. Gender differences in perceived intimacy with different members of adolescents' social networks. Sex Roles. 1987;17:689–718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00287683. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Hill J, Thiel K. Early adolescents' significant others: grade and gender differences in perceived relationships with familial and non-familial adults and young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1982;11:425–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01538805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01538805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D, Bukowski WM. Same-sex peer relations and romantic relationships during early adolescence: Interactive links to emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:77–103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2002.0001. [Google Scholar]

- Bucx F, Seiffge-Krenke I. Romantic relationships in intra-ethnic and inter-ethnic adolescent couples in Germany: the role of attachment to parents, self-esteem, and conflict resolution skills. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:128–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165025409360294. [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. 2010 Retrieved from http://statmodel2.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- Collins WA. More than myth: the developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.1301001. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/ annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, McIsaac C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 104–151. [Google Scholar]

- Crissey SR. Race/ethnic differences in marital expectations of adolescents: the role of romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:697–709. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00163.x. [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Warber KM. Social networking sites in romantic relationships: attachment, uncertainty, and partner surveillance. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2014;17:3–7. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Pederson S. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:856–868. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.856. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner EA. Romantic views: toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Montemayor R, Adams G, Gullotta T, editors. Personal relationships during adolescence. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. pp. 168–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Germán M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett FC, Millsap R, et al. Mexican American adolescents' cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: the role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Dishion T, Overbeek G, Burk WJ, Engels RCME. The blues of adolescent romance: observed affective interactions in adolescent romantic relationships associated with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9808-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9808-y. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hendrick SS. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:93–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/352430. [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Natsuaki MN, Zhang J, Guo F, Huang Z, Wang M, et al. Romantic relationships and adjustment problems in China: the moderating effect of classroom romantic context. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.10.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles E, Garrido E, Rosenfield D, McDonald R. Experiences of psychological and physical aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: links to psychological distress. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, et al. The Mexican American culture values scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ biomet/88.3.767. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanai L, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D. Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: the roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubke GH, Muthén BO. Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychological Methods. 2005;10:21–39. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.21. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Maehr ML, Urdan T. Patterns of adaptive learning survey (PALS) University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor: 1996. Retrieved from http://www.umich.edu/~pals/PALS%202000_V13Word97.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Millbrath C, Ohlson B, Eyre SL. Analyzing cultural models in adolescent accounts of romantic relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:313–351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00598.x. [Google Scholar]

- Motel S, Patten E. Statistical profile: Hispanics of Mexican origin in the United States, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center; Pew Research Center: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2012/06/2010-Mexican-Factsheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Christofides E, Desmarais S. “Creeping” or just information seeking? Gender differences in partner monitoring in response to jealousy on Facebook. Personal Relationships. 2013 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pere.12014. Advance online publication.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. Basic Books; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: what changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07399863870094003. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:519–531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000145. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV: description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Kerns D. Unwanted sexual activity among peers during early and middle adolescence: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:941–952. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/352774. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrell FA, Wheeler LA, Gonzales NA, Dumka L, Millsap R. Family influences on Mexican American adolescents' romantic relationships: moderation by gender and culture. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jora.12177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jora.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale SM, Wheeler LA, Perez-Brena NJ. Mexican-origin youth's cultural orientations and adjustment: changes from early to late adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83:1655–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01800.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-624.2012.01800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujeva HM, Furman W. Depressive symptoms and romantic relationship qualities from adolescence through emerging adulthood: a longitudinal examination of influences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:123–135. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.533414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Adams HL. Parties, drugs, and high school hookups: socioemotional challenges for European and Mexican American adolescents. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work. 2013;28:240–255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886109913495728. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Hickle KE. “He cheated on me, I cheated on him back”: Mexican American and White adolescents' perceptions of cheating in romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Cowen EL, Work WC, Kerley JH. The role of children's future expectations in self-esteem functioning and adjustment to life stress: a prospective study of urban at-risk children. Developmental Psychopathology. 1993;5:649–661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006210. [Google Scholar]

- Yan FA, Howard DE, Beck KH, Shattuck T, Hallmark-Kerr M. Psychosocial correlates of physical dating violence victimization among Latino early adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:808–831. doi: 10.1177/0886260509336958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260509336958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Roosa MW, Knight GP, Gonzales NA. Mexican American adolescents' profiles of risk and mental health: a person-centered longitudinal approach. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:603–612. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Collins A. Gender, mature appearance, alcohol use, and dating as correlates of sexual partner accumulation from ages 16–26 years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Sibenbruner J, Collins WA. Diverse aspects of dating: associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:313–336. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]