Abstract

Objective

In adults, gadolinium contrast-enhancement does not add incremental value to fluid sensitive sequences for evaluation of bone marrow edema. This study aimed to determine if magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast is necessary to assess lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children.

Methods

Subjects with clinically suspected or diagnosed JSpA underwent pelvic MRI consisting of multiplanar fluid sensitive- and post-gadolinium T1-weighted fat saturated sequences including dedicated sacral imaging. Three radiologists independently evaluated the fluid-sensitive sequences, and later, the complete study (including post-contrast imaging). With post-contrast imaging as the reference standard we calculated the test properties of fluid sensitive sequences for depiction of acute and chronic findings consistent with sacroiliitis.

Results

Fifty-one subjects had a median age of 15 years and 57% were male. Nineteen subjects (22 joints) were diagnosed with sacroiliitis based on post-contrast imaging and none had synovitis in the absence of bone marrow edema. All 22 joints demonstrated bone marrow edema on both fluid sensitive- and post-gadolinium T1-weighted fat saturated sequences. Eighteen percent of joints with sacroiliitis had capsulitis, which was depicted on both non-contrast and post-contrast imaging. Fifty-nine percent of joints with sacroiliitis had synovitis on post-contrast imaging. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of fluid-sensitive sequences for the detection of acute inflammatory lesions consistent with sacroiliitis using post-gadolinium imaging as the reference standard were excellent. Inter-rater reliability was substantial for all parameters.

Conclusions

Fluid sensitive sequences are sufficient to detect acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children.

INTRODUCTION

Children and adolescents with juvenile spondyloarthritis (JSpA) are at risk of developing sacroiliitis, or inflammation of the sacroiliac joints. In children with JSpA, early identification of sacroiliitis with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an opportunity to alter the disease course. Active inflammatory lesions of the sacroiliac joints attributable to JSpA include bone marrow edema, sacroiliac joint synovitis, erosions, enthesitis, and capsulitis. Sacroiliitis on MRI is defined in adults by the Assessment of SponyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria as the presence of subchondral or periarticular bone marrow edema (1). The presence of synovitis, enthesitis, and capsulitis are supportive of the diagnosis of sacroiliitis, but when present in the absence of bone marrow edema are not sufficient to define sacroiliitis.(1) In adults, synovitis, enthesitis, and capsulitis seldom occur in the absence of typical bone marrow edema (2, 3). The frequency of these inflammatory lesions in the absence of bone marrow edema in children is unknown.

The current gold standard in adults for the detection of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis is dedicated pelvic MRI imaging with fluid sequences, including Short T1 Inversion Recovery (STIR) (1, 4, 5). While both fluid sensitive- and fat-saturated (fs) post contrast sequences can identify enthesitis/capsulitis and bone marrow edema, fat-saturated post contrast sequences can distinctly identify synovitis. In adults, multiple studies have shown that since synovitis rarely occurs in the absence of bone marrow edema gadolinium-enhancement does not add incremental value to fluid sensitive sequences (2, 3, 6–8). Despite the published reports in adults, the use of gadolinium to evaluate for acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children is common practice.

The use of gadolinium contrast agents in children for the detection of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis has implications such as: need for vascular access, longer study times which may necessitate the use of sedation, potential adverse contrast events and increased cost. MRI of the sacroiliac joint does not require vascular access in children unless intravenous (IV) sedatives or contrast agents are required. IV catheter placement may cause intense anxiety (for both the parent and the child) and pain (9–11). The time needed to acquire additional sequences after contrast administration is approximately 10 minutes in the scanner. If a child needs sedation for the imaging then that additional time could result in additional sedative administration. Administration of gadolinium contrast also has some potential adverse effects, namely the risk for severe allergic reaction and nephropathy including nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (12–15). The mechanism of gadolinium toxicity in the kidneys is unclear but thought to include vasoconstriction leading to hypoxic tubular cell injury (16). Those children and adults with renal failure are at the highest risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (16). Lastly, administration of contrast adds costs; at our institution the use of contrast to image the sacroiliac joints adds approximately $1800.

Given that the use of gadolinium in children is not risk-free, it should not be used indiscriminately for the evaluation of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis unless it adds incremental value to fluid sensitive sequences. The purpose of this study was to determine if MRI contrast is necessary to assess for sacroiliitis in patients with clinically suspected or diagnosed JSpA. With post-contrast imaging as the reference standard we aimed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of fluid sensitive sequences for the depiction of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) approved the protocol for the conduct of this study.

Study subjects

Subjects included males or females who underwent MRI imaging of the pelvis consisting of multiplanar fluid sensitive- and post-gadolinium T1-weighted fat saturated sequences that included small field-of-view coronal oblique imaging of the sacrum between January 2002 and April 2014 at our institution.

Clinical data

Demographics and indication for imaging were abstracted from the electronic medical health record.

Imaging

All pelvis and hip MRI images in our radiology picture archiving and communication system (PACS) from January 2002 to April 2014 were queried to identify the terms "sacroiliitis", “arthritis”, “pain”, “stiffness”, “spondyloarthritis”, “inflammation” and “spondyloarthropathy” in the requisition or study report using the Softek Illuminate search engine (N=97). All images were screened to ensure that both fluid sensitive sequences and fat-saturated T1 weighted post-contrast images were obtained (N=95). Only studies with dedicated pelvic images, defined as inclusion of a coronal oblique (parallel to the long axis of the sacrum) view of the sacrum were included (N=54). All records were screened to verify that the imaging was ordered as part of an evaluation for known or suspected JSpA (N=51). Magnet strength was 1.5 (N=27) or 3.0 (N=24) tesla. MRI slices through the sacrum were 3 mm thick.

All fluid sensitive sequences and fat-saturated (fs) T1 weighted post-contrast images were de-identified and read by 3 pediatric radiologists with experience in musculoskeletal imaging (NAC, DMB, AMJ). Three radiologists, blinded to clinical details, independently evaluated the non-contrast sequences, and at a later date, the complete study (including post-contrast imaging) in randomized order. Images were evaluated for the presence of bone marrow edema, capsulitis, effusion and synovitis (post-contrast sequences only). During an initial consensus review of five cases, which were not included in our study, standards of interpretation and terminology were established. To avoid interpretation fatigue the readings were done in sets of 8 studies, with a maximum of 1 set interpreted at a time. Findings were considered positive if noted by 2 of the 3 radiologists.

The ASAS/OMERACT definitions of active inflammatory lesions including bone marrow edema, synovitis, capsulitis, enthesitis were used for this study (6). Bone marrow edema was defined as hyperintense signal on T2 weighted fs imaging or STIR images. If there was one detectable lesion, then the lesion had to be present on more than one consecutive imaging slice. If there was more than one lesion present on a single slice, then 1 slice was considered sufficient evidence of inflammation (1). In children who were skeletally immature, care was taken to avoid calling bone marrow edema positive in subjects with relatively hyperintense apophyseal cartilage adjacent to the sacroiliac joints (7). In these patients, edema was diagnosed when the STIR signal was hyperintense relative to the signal in the visualized metaphyseal equivalents (ie iliac crest apophyses), which were used as reference standards. Sacroiliitis was defined as the presence of bone marrow edema in periarticular areas. Synovitis was defined as abnormal synovial enhancement in the inferior aspect of the joint, based on prior studies that demonstrated true synovial lining is confined to the distal third of the joint (17). Capsulitis was defined as hyperintense fluid sensitive signal or abnormal enhancement adjacent to the anterior or posterior sacroiliac joint capsule. Enthesitis was defined as increased fluid sensitive signal or abnormal enhancement within the ligamentous aspects of the joint.

The ASAS/OMERACT definitions of structural damage lesions including sclerosis and erosions were used for this study (6). Sclerosis was defined as low or absent signal that extends at least 5 mm from the SI joint space. Erosions were defined as bony defects along the sacroiliac joint margin with low and high signals on T1-weighted and STIR sequences, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Demographic information and characteristics were summarized by frequencies and percentages for categorical values and by mean, standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate, for continuous variables. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of fluid sensitive sequences for depiction of sacroiliitis were calculated using post-contrast imaging as the reference standard. The inter-rater reliability of the MR interpretation for bone marrow edema, capsulitis, effusion and synovitis was measured with Fleiss’ kappa coefficients.(18) Enthesitis and capsulitis as well as erosions and sclerosis were pooled for the purposes of assessing reliability given the low numbers of abnormal findings. According to Landis and Koch(19), a kappa value of less than or equal to 0.40 indications poor, 0.41–0.59 fair, 0.60–0.74 good, and equal to or greater than 0.75 excellent agreement. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 13 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Subjects

Images from fifty-one subjects with clinically suspected or diagnosed JSpA were included. Subjects had a median age of 15 years (IQR: 13, 16; range: 4–19). Eleven children were older than 16 years at the time imaging but each had symptom onset prior to age 16. Twenty-nine (57%) were male. Seventy-five percent, 18%, 6%, and 2% were Caucasian, black, Asian, or “other” race, respectively. The indication for imaging was back pain in 46 (90%), hip pain in 3 (6%), and decreased back flexion in 2 (4%). After imaging 43 subjects had a confirmed JSpA diagnosis and 8 were diagnosed with other conditions including infection (N=2), fibromyalgia (N=1), and back pain not otherwise specified (N=5). All children with JSpA met International League of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for enthesitis-related arthritis (N=31), psoriatic arthritis (N=4) or European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group Criteria for SpA (N=8).

MRI findings

MRI results are presented in Table 1. Twenty-two joints in 19 subjects were diagnosed as sacroiliitis based on post-contrast imaging, using the ASAS criteria(1). All 20 joints demonstrated bone marrow edema on both fluid sensitive and post-gadolinium T1-weighted fs sequences (Figures 1 and 2). The majority of capsulitis, effusions, and erosive lesions were visualized on both fluid sensitive and post-gadolinium images. Two cases of enthesitis were seen only on fluid sensitive images. In those few instances where erosions (N=4) or sclerosis (N=1) were detectable solely on the full study with post-contrast images the diagnosis of sacroiliitis did not change as they all occurred in the presence of bone marrow edema on fluid-sensitive sequences. Thirteen joints had detectable synovitis on post-contrast imaging. Care was taken to avoid calling bone marrow edema positive in subjects with relatively hyperintense apophyseal cartilage adjacent to the sacroiliac joints (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Sacroiliac lesions detected on MRI (N=102 joints)

| Positive findings, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid sensitive and full study |

Fluid- sensitive only |

Full study only |

|

| Bone marrow edema | 22 (22) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Enthesitis | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Capsulitis | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Synovitis | -- | -- | 13 (13) |

| Joint effusion | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Erosions | 10 (10) | 1(1) | 4 (4) |

| Sclerosis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

Active inflammatory sacroiliac lesions detected on both fluid sensitive (non-contrast) sequences and the full study (including the post-contrast sequences) (Column 1); fluid sensitive sequences only (Column 2); full study including post-contrast sequences only (Column 3). Findings were considered positive if noted by at least of 2 of the radiologists.

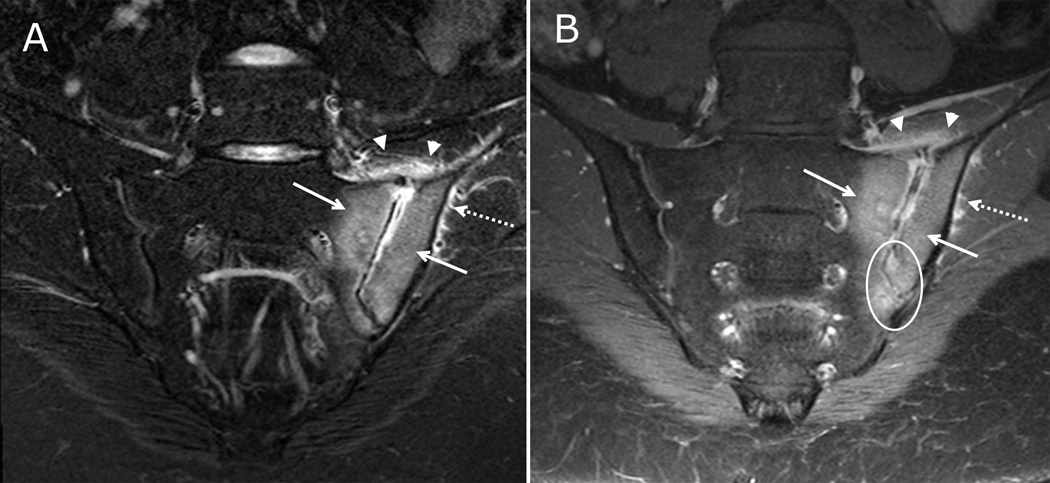

Figure 1. Active inflammatory lesions of the sacroiliac joints visible on both fluid-sensitive and post-contrast sequences.

17-year-old male with left lower back pain. (A) Coronal oblique STIR imaging of the sacrum demonstrates bone marrow edema within the inferior periarticular aspect of right iliac bone (solid arrow). There is a small amount of joint fluid within the inferior aspect of the joint (arrowhead). A normal hyperintense subchondral stripe is seen on the left in this skeletally immature child (dashed arrow). (B) Coronal oblique T1 weighted post contrast imaging of the sacrum demonstrates enhancing bone marrow edema within the inferior right iliac bone (solid arrow) and adjacent synovitis within the inferior, ventral aspect of the joint (arrowheads) with adjacent periarticular enhancement which is greater on the iliac side. There is a normal, mild enhancement of the left segmental sacral apophyses (dashed arrow).

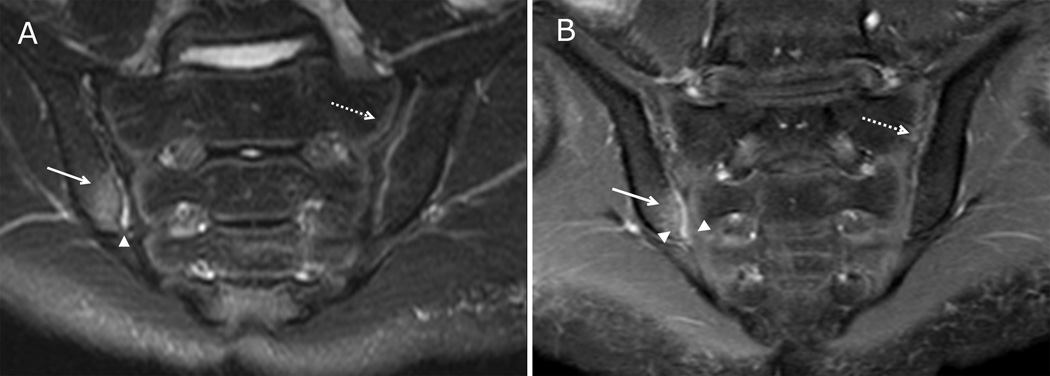

Figure 2. Active inflammatory lesions and normal findings in skeletally immature sacroiliac joints visible on both fluid-sensitive and post-contrast sequences.

8 year-old male with right lower back pain. (A) Coronal oblique STIR imaging of the sacrum demonstrates periarticular bone marrow edema within the left sacrum and left iliac bone (solid arrows). There is a small amount of joint fluid within the left sacroiliac joint with adjacent capsular edema (arrowheads). There is edema at the gluteal muscle origin (dashed arrow). (B) Coronal oblique T1 weighted post contrast imaging of the sacrum demonstrates enhancing periarticular bone marrow (solid arrows), adjacent synovitis (circle) as demonstrated by periarticular enhancement within the inferior, synovial lined portion of the joint space, capsulitis (arrowheads) and enhancing inflammation at the gluteal muscle origin (dashed arrow).

Using the full study that included post-contrast sequencing as the reference standard 0%, 18%, and 59% of joints with sacroiliitis also had enthesitis, capsulitis, or synovitis depicted, respectively. All cases of capsulitis and synovitis that were detected on the full study (including post-contrast sequences) occurred in the presence of bone marrow edema (Table 2).

Table 2.

Active inflammatory sacroiliac lesions detected on MRI in the presence or absence of bone marrow edema (N=102 joints)

| Positive findings, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow edema positive N=22 |

Bone marrow edema negative N=77 |

||

| Enthesitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Capsulitis | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | |

| Synovitis | 13 (59) | 0 (0) | |

Active inflammatory sacroiliac lesions detected on the full study (including the post-contrast sequences) in the presence or absence of bone marrow edema on the non-contrast images.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of fluid-sensitive sequences for the detection of bone marrow edema using the full study with post-gadolinium sequences as the reference standard were near perfect (Table 3).

Table 3.

Test properties of sacroiliitis depicted by fluid-sensitive sequences, using the full study with post-contrast sequences as the reference standard

| Sacroiliitis diagnosed on fluid sensitive sequences |

Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 1.00 (0.85, 1.00) |

| Specificity | 0.96 (0.89, 0.99) |

| Positive predictive value | 0.88 (0.69, 0.97) |

| Negative predictive value | 1.00 (0.95, 1.00) |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values of sacroiliitis diagnosed on fluid-sensitive sequences using the full study that included post-gadolinium enhanced sequences as the reference standard.

Five patients had bone marrow edema in the pelvis or hips that was not periarticular. Only one of these patients did not also have periarticular bone marrow edema. Sites of this non-specific edema included the less trochanter, greater trochanter apophysis, femoral heads and S2.

Reliability of MRI findings

All fluid sensitive sequences and fs T1 weighted post-contrast images were de-identified and read by 3 pediatric radiologists with experience in musculoskeletal imaging. Each radiologist independently evaluated the non-contrast sequences, and at a later date, the complete study (including post-contrast imaging) in randomized order. Inter-rater reliability using Fleiss’ kappa was substantial (>0.60) for all parameters except for the presence of capsulitis or enthesitis on the full study including post-contrast images (Table 4).

Table 4.

Inter-rater reliability for active inflammatory lesions of the sacroiliac joints

| Findings | Fless’ kappa (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Fluid sensitive sequences | |

| BME | 0.81 (0.70, 0.92) |

| Capsulitis/Enthesitis | 0.62 (0.51, 0.74) |

| Erosions/Sclerosis | 0.61 (0.50, 0.72) |

| Full study including post-contrast sequences | |

| BME | 0.71 (0.60, 0.82) |

| Capsulitis/Enthesitis | 0.50 (0.39, 0.61) |

| Synovitis | 0.61 (0.49, 0.72) |

| Erosions/Sclerosis | 0.75 (0.64, 0.86) |

Inter-rater reliability of 3 pediatric radiologists for the detection of active inflammatory lesions of the sacroiliac joint. According to Landis and Koch(19), a kappa value of 0.60–0.74 indicates good agreement and a kappa value equal to or greater than 0.75 indicates excellent agreement.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to systematically evaluate the utility of contrast for the detection of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children with suspected or known JSpA. In this cross-sectional retrospective study we found that the use of gadolinium-enhanced sequences did not add incremental value to fluid sensitive sequences for the detection of acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in the pediatric population. In a setting of clinical suspicion for SpA, according to the ASAS criteria(1), the presence of subchondral or peri-articular bone marrow edema is sufficient to make a diagnosis of sacroiliitis in adults. In our study there were 22 joints with active sacroiliitis. Eighteen percent and 59% of joints with sacroiliitis also had capsulitis or synovitis depicted, respectively. The prevalence of these supportive lesions in our cohort is in accordance to what has been published in the adult literature (2). Gadolinium did not enhance the ability to detect bone marrow edema or capsulitis but did enable detection of synovitis. All cases of synovitis and capsulitis were coincident with bone marrow edema on fluid-sensitive sequences. Lastly, inter-rater reliability amongst three pediatric radiologists for bone marrow edema was nearly perfect.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, our sample size was limited at 51 children (102 sacroiliac joints). However, despite the limited sample size it is the first study to systematically evaluate the utility of contrast to detect bone marrow edema and other acute and chronic changes that are consistent with sacroiliitis in children. Second, because this wasn’t a prospective study there was not uniformity in the MRI sequences obtained. All studies did include oblique coronal views to ensure adequate visualization of the sacroiliac joints. While this impacts uniformity of image attainment, it may actually provide greater generalizability of our findings. A variety of sequence protocols exist across care centers, and both 1.5 and 3.0 tesla magnets are used in everyday practice.

A few findings from this study warrant additional discussion. First, both fluid sensitive and gadolinium-enhanced sequences can be used to detect acute and chronic lesions consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children, as evidenced by the substantial Fleiss kappa values in our study. However, as aforementioned the administration of contrast is not without consequences in children, ranging from pain and anxiety (secondary to IV catheter placement) to the risk of severe contrast allergic reaction. Although gadolinium did enhance detection of synovitis, this finding was uniformly in the presence of bone marrow edema and therefore did not alter the final diagnosis.

Second, currently there is no uniformly accepted definition of pediatric sacroiliitis. Since all cases of synovitis, capsulitis, and enthesitis were coincident with bone marrow edema on fluid-sensitive sequences we believe that the ASAS criteria(1) for sacroiliitis are applicable in children. Since interpretation of synovitis, capsulitis, and enthesitis can vary greatly amongst radiologists as evidenced by the Fleiss kappa from this study, interpretation of these features as supportive but not diagnostic in children will reduce the likelihood of false positive diagnoses. Additionally, MRI findings need to be clinically correlated taking into consideration the pre-test probability and strength of clinical suspicion. Indeed, our findings are not in agreement with a recent case series that suggested synovial enhancement could be seen in the absence of bone marrow edema in children; in that study 1/3 of cases of sacroiliitis were based on the presence of synovitis in the absence of bone marrow edema (20). A precise definition for synovitis in the study by Lin et al. was not provided and we suspect that the threshold for calling synovitis positive was lower than in this study. Histopathologic studies with MRI evaluation have shown that a true synovium is only in the inferior aspect of the joint (17). Thus when joint capsule enhancement is seen in more proximal aspects, a finding of synovitis may be overcalled. Accurate diagnosis of sacroiliitis in children has important implications for treatment decisions, namely use of a TNF inhibitor, and future disease monitoring.

Lastly, based on the variety of images reviewed in this study we suggest that the optimal sequences for evaluation of sacroiliitis in children are the following: oblique coronal STIR, T1 turbo spin echo, and axial T2 fs through the sacroiliac joints; coronal T2 fs of the entire pelvis; and large field of view images to screen for hip pathology. Prior studies correlating MRI to histological findings in adults have demonstrated that the ventral and dorsal aspects of the sacroiliac joints are only visible with oblique imaging (17). These studies recommend inclusion of oblique coronal T1 sections as well as oblique axial STIR/T2 fs for adequate assessment of the entire joint (17).

In summary, this is the first study to demonstrate that gadolinium-enhanced sequences are not necessary to evaluate for acute and chronic changes consistent with inflammatory sacroiliitis in children with suspected or diagnosed with JSpA. There may be cases in which alternative diagnoses are being entertained, such as infection or tumor, in which the use of gadolinium may still be advisable. Avoidance of unnecessary gadolinium contrast will save time in the scanner, healthcare dollars, and will obviate the need for pre-contrast screening blood tests and IV placement unless needed for sedation or other purposes.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03-AR062665. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and dose not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Pamela F Weiss, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Center for Pediatric Clinical Effectiveness, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Rui Xiao, Department of Biostatistics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

David M Biko, Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Ann M Johnson, Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Nancy A Chauvin, Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–ii44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maksymowicz H, Kowalewski K, Lubkowska K, Zolud W, Sasiadek M. Diagnostic value of gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging of active sacroiliitis in seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Pol J Radiol. 2010;75(2):58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Hooge M, van den Berg R, Navarro-Compan V, van Gaalen F, van der Heijde D, Huizinga T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joints in the early detection of spondyloarthritis: no added value of gadolinium compared with short tau inversion recovery sequence. Rheumatology. 2013;52(7):1220–1224. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuite MJ. Sacroiliac joint imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008;12(1):72–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puhakka KB, Jurik AG, Egund N, Schiottz-Christensen B, Stengaard-Pedersen K, van Overeem Hansen G, et al. Imaging of sacroiliitis in early seronegative spondylarthropathy. Assessment of abnormalities by MR in comparison with radiography and CT. Acta Radiol. 2003;44(2):218–229. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2003.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, Jurik AG, Hermann KG, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, et al. Defining active sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: a consensual approach by the ASAS/OMERACT MRI group. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009;68(10):1520–1527. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.110767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navallas M, Ares J, Beltran B, Lisbona MP, Maymo J, Solano A. Sacroiliitis associated with axial spondyloarthropathy: new concepts and latest trends. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America Inc. 2013;33(4):933–956. doi: 10.1148/rg.334125025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen KB, Egund N, Jurik AG. Grading of inflammatory disease activity in the sacroiliac joints with magnetic resonance imaging: comparison between short-tau inversion recovery and gadolinium contrast-enhanced sequences. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(2):393–400. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey GB, Boon CM, van Linden van den Heuvell GF, van de Wiel HB. The occurrence of high levels of acute behavioral distress in children and adolescents undergoing routine venipunctures. Pediatrics. 1992;90(1 Pt 1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings EA, Reid GJ, Finley GA, McGrath PJ, Ritchie JA. Prevalence and source of pain in pediatric inpatients. Pain. 1996;68(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polkki T, Pietila AM, Rissanen L. Pain in children: qualitative research of Finnish school-aged children's experiences of pain in hospital. International journal of nursing practice. 1999;5(1):21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1999.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, Robin HS, LeBoit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2001;23(5):383–393. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, Kurtz K. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):903–906. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeBoit PE. What nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy might be. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):928–930. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomsen HS, Morcos SK. Contrast media and the kidney: European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines. Br J Radiol. 2003;76(908):513–518. doi: 10.1259/bjr/26964464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puhakka KB, Melsen F, Jurik AG, Boel LW, Vesterby A, Egund N. MR imaging of the normal sacroiliac joint with correlation to histology. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(1):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin. 1971;76(5):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin C, MacKenzie JD, Courtier JL, Gu JT, Milojevic D. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in juvenile spondyloarthropathy and effects of treatment observed on subsequent imaging. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12:25. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]