Abstract

Objectives

The relationship of specific psychiatric conditions to adherence has not been examined in longitudinal studies of youth with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV). We examined associations between psychiatric conditions and ARV non-adherence over two years.

Design

Longitudinal study in 294 PHIV youth, 6–17 years old, in the US and Puerto Rico.

Methods

We annually assessed three non-adherence outcomes: missed >5% of doses in past 3 days, missed a dose within the past month, and unsuppressed viral load (VL) (>400 copies/mL). We fit multivariable logistic models for non-adherence using Generalized Estimating Equations and evaluated associations of psychiatric conditions (ADHD, disruptive behavior, depression, anxiety) at entry with incident non-adherence using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Non-adherence prevalence at study entry was 14% (3-day recall), 32% (past month non-adherence), and 38% (unsuppressed VL), remaining similar over time. At entry, 38% met symptom cutoff criteria for ≥1 psychiatric condition. Greater odds of 3-day recall non-adherence were observed at Week 96 for those with depression (Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR)=4.14; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11–15.42) or disruptive behavior (aOR=3.36; 95% CI: 1.02–11.10) but not at entry. Those with vs. without ADHD had elevated odds of unsuppressed VL at Weeks 48 (aOR=2.46; 95% CI: 1.27–4.78) and 96 (aOR=2.35; 95% CI: 1.01–5.45) but not at entry. Among 232 youth adherent at entry, 16% reported incident 3-day recall non-adherence. Disruptive behavior conditions at entry were associated with incident 3-day recall non-adherence (aOR=3.01; 95% CI: 1.24–7.31).

Conclusions

In PHIV youth, comprehensive adherence interventions that address psychiatric conditions throughout the transition to adult care are needed.

Keywords: adherence, mental health, adolescents, perinatal HIV infection, longitudinal

BACKGROUND

Due to dramatic improvements in combination antiretroviral therapy (ARV) and clinical care, more children with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) are approaching adolescence and young adulthood. Approximately 3.2 million children under 15 years old worldwide are living with HIV infection [1], and in the US, 75% of the estimated 10,000 youth with PHIV are now over 15 years old [2]. Near-perfect adherence to ARV is recommended to achieve viral suppression, slow disease progression, and prevent drug-resistance and HIV transmission [3–4]. Adherence is particularly important as youth with PHIV age and become sexually active [5], assume responsibility for managing their HIV disease, and transition from pediatric to adult care. It is therefore imperative to identify factors associated with non-adherence in order to develop strategies to support ARV adherence in youth with PHIV.

Youth with HIV have high rates of psychiatric conditions exceeding those in the general population [6–10]. Mental health problems co-occur with suboptimal adherence [11]. Behavioral impairment [12], diagnosis of depression [13] or anxiety, or conduct disorder [12,14] have been associated with non-adherence, although findings have been mixed [15–17].

Adherence is a dynamic behavior that fluctuates [18]. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship of psychiatric conditions to later antiretroviral non-adherence in initially adherent youth with PHIV. However, one study of youth with non-perinatally-acquired HIV showed that among 65 adherent 15–22 year-olds, being depressed and younger was associated with becoming non-adherent over twelve months [13]. In two longitudinal studies of adherence in youth with PHIV, one (n=138) showed no association between emotional problems and non-adherence [17], another (n=108) did not evaluate psychiatric conditions [19]; neither evaluated predictors of becoming non-adherent. Almost all studies examining mental health and ARV adherence have either been cross-sectional [12,14–16], focused on youth with non-perinatally-acquired HIV [13] or did not distinguish between HIV acquisition modes [14], used one ARV adherence measure [12, 14, 16–17], or relied on psychiatric information from claims or medical records [14–16].

We address previous gaps by using a longitudinal design, a focus on youth with PHIV in the combination antiretroviral therapy era, well-validated measures of psychiatric symptoms, a larger sample size, longer observational period, and multiple adherence measures. The objectives were to 1) evaluate the association between psychiatric symptoms and non-adherence to ARV and unsuppressed viral load (VL) over time in youth with PHIV; 2) determine the association between psychiatric conditions at entry and a) becoming non-adherent at follow-up in those who reported being adherent at entry, and b) loss of virologic suppression at follow-up in youth with suppressed VL at entry.

METHODS

Study Population

The International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) P1055 study was a two-year multi-site prospective study that evaluated the prevalence and severity of psychiatric symptoms in youth with PHIV and youth a) perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected and/or b) uninfected and living in households with HIV-infected members. Youth were enrolled and followed during 2005–2008, at 29 sites in the United States, including Puerto Rico. Inclusion criteria were: 6–17 years old at enrollment, living with their primary caregiver ≥12 months, and IQ≥70. Youth and caregivers completed assessments at entry, 48 weeks and 96 weeks. Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at each site approved the study. Staff obtained written informed consent from caregivers, and assent from youth as allowed by the site IRBs. Methods are described in detail elsewhere [18,20–22]. This analysis included only participants with ≥1 follow-up visit and ≥1 visit in which they were prescribed ARV, and had adherence and psychiatric symptoms information.

Measures

Non-adherence

We assessed three ARV non-adherence outcomes at each study time point: 1) self-reported 3-day recall non-adherence, 2) self-reported past month non-adherence, and 3) unsuppressed VL. We obtained self-reported adherence through interviews with the youth and/or caregiver. We used the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Module [23] to measure three-day recall non-adherence, defined as taking <95% of prescribed ARV doses in the past 3 days. To report past month non-adherence, defined as missing a dose during the past month, vs. never, over one month ago, or not recalled, participants were asked about when they last missed a medication (ARV or psychotropic medications). Unsuppressed VL was defined as HIV RNA >400 copies/mL based on the most recent HIV RNA measurement (≤90 days prior to study visit) abstracted from medical records.

Psychiatric Conditions

At each visit, youth reported on their own psychiatric symptoms, and primary caregivers rated their children’s symptoms by completing validated, self-administered rating scales based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Primary caregivers completed the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R, which assesses psychiatric symptoms in children ages 5–18 [24]. Children ages 12–18 completed the Youth’s (Self Report) Inventory 4-R (YI-4R) [25–26]. Children ages 8 to < 12 completed the Child (Self Report) Inventory-4 [27], an abbreviated version of the YI-4R that excludes assessment of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) (disruptive behavior disorders) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) due to concerns about the validity of self-assessment of these symptoms by young children; thus, for children 8 to <12, determination of ADHD and disruptive behavior symptomatology was based on caregiver ratings only. Validated Spanish versions were also available. When the symptom score for a given condition reported by either child or caregiver equaled or exceeded the threshold necessary for a DSM-IV diagnosis, the child was classified as meeting symptom cutoff criteria. This analysis focused on the most prevalent conditions in this population, grouped into four domains: any type of ADHD, depression (major depression or dysthymia), disruptive behavior (ODD or CD), and anxiety (generalized or separation anxiety). We also created a composite indicator, defined as meeting symptom cutoff criteria for at least one of these four targeted conditions.

Other Covariates

To describe the study population and compare adherent to non-adherent youth, we examined demographic, family, psychosocial, ARV use, HIV disease and mental health treatment characteristics. We considered the following subset of potential confounders that were not on the causal pathway between psychiatric disorders and non-adherence as candidates for inclusion in multivariable models based on results of prior studies: age, gender, race/ethnicity, annual income, study entry CD4 count, and protease inhibitor use history.

Statistical Analyses

We compared entry characteristics of adherent vs. non-adherent youth for all three non-adherence outcomes, and evaluated differences using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. We estimated the prevalence of non-adherence and psychiatric conditions at entry, 48 weeks, and 96 weeks. To evaluate associations of each psychiatric condition and each of the three non-adherence outcomes over time, we fitted unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to account for within-person correlation in the repeated measures for each participant, assuming an exchangeable covariance structure. We also tested whether the association between psychiatric conditions and non-adherence varied over time by including an interaction between psychiatric condition and visit. When the p-value for the interaction was ≤ 0.10, we calculated predicted probabilities of non-adherence at each time point in those with vs. without the psychiatric condition, adjusting for other covariates. Adjusted models controlled for the subset of variables with p-value<0.20 in unadjusted models and p-value<0.10 in multivariable models, with a separate model developed for each non-adherence outcome. In modeling lack of virologic suppression, we conducted sensitivity analyses restricting analyses to youth with 3-day recall adherence data.

To examine the association between each psychiatric condition at entry and incident non-adherence, we restricted analyses to youth who were adherent (or virally suppressed) at entry, and fit unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models, with covariates in adjusted models selected using the procedures above. We defined incident non-adherence as non-adherence at either Week 48 or 96, and loss of virologic suppression as VL>400 at either Week 48 or 96.

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Owing to the exploratory nature of the analyses, no corrections were made for multiple comparisons; however, particular attention in interpretation was given to consistencies in observed findings. The significance criterion was a 2-sided p-value<0.05.

RESULTS

Of 319 youth with PHIV enrolled in P1055, 296 had at least one follow-up visit. Within this group, two participants who reported never receiving ARV during the study were excluded. All 294 remaining were evaluable for VL suppression, 270 had information allowing evaluation of 3-day recall non-adherence, and 272 were included in evaluation of past-month non-adherence. The sample size for the unsuppressed VL analyses included data from youth without self-reported adherence information and from visits when youth were not on ARVs. There were few differences between the 270 youth who were included and 24 youth excluded from the analysis of non-adherence by 3-day recall. Excluded youth were more frequently older (16–18), had lower median CD4 count, and were not on ARVs at study entry. For 83% of excluded youth, the adherence questionnaire was not completed because the participant was not on ARVs.

Among the 294 participants, about half were girls, most were black or Hispanic, and 52% were between 13 and 17 (Table 1). Demographic characteristics of youth who were non-adherent at entry did not differ from those who were adherent for the 3-day recall and past month non-adherence outcomes; however youth with unsuppressed VL more frequently were black, Hispanic, older, or were from a household with an annual household income <$20,000 compared to youth with suppressed VL at entry. Participants who were non-adherent at entry (for either self-report adherence outcome) more frequently had used protease inhibitors and participants who were non-adherent by 3-day recall more frequently had CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3 compared to adherent participants. The proportion using psychotropic medications did not differ by adherence status for either of the self-reported adherence outcomes, but was lower among youth with unsuppressed vs. suppressed VL.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic, Health and Regimen Characteristics and Non-Adherence among 294 Youth in the IMPAACT P1055 Study: 2005–2008

| Characteristic | 3-day Recall Non-Adherence | Missed Dose Within Past Month | Lack of VL Suppression | TOTAL (294) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (38) |

No (232) |

p-value | Yes (86) |

No (186) |

p-value | Yes (113) |

No (181) |

p-value | |||

| Female | 19 (50%) | 112 (48%) | 0.86 | 42 (49%) | 90 (48%) | 1.00 | 54 (48%) | 91 (50%) | 0.72 | 145 (49%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White Non-Hispanic, Asian or other | 5 (13%) | 33 (14%) | 0.76 | 12 (14%) | 27 (15%) | 0.97 | 9 (8%) | 34 (19%) | 0.04 | 43 (15%) |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 23 (61%) | 126 (54%) | 48 (56%) | 101 (54%) | 67 (59%) | 92 (51%) | 159 (54%) | ||||

| Hispanic (Regardless of Race) | 10 (26%) | 73 (31%) | 26 (30%) | 58 (31%) | 37 (33%) | 55 (30%) | 92 (31%) | ||||

| Age in years | 6 – <10 | 6 (16%) | 51 (22%) | 0.18 | 13 (15%) | 44 (24%) | 0.19 | 14 (12%) | 44 (24%) | 0.01 | 58 (20%) |

| 10 – <13 | 7 (18%) | 71 (31%) | 23 (27%) | 56 (30%) | 31 (27%) | 54 (30%) | 85 (29%) | ||||

| 13 – <16 | 15 (39%) | 73 (31%) | 30 (35%) | 58 (31%) | 37 (33%) | 56 (31%) | 93 (32%) | ||||

| 16 – <18 | 10 (26%) | 37 (16%) | 20 (23%) | 28 (15%) | 31 (27%) | 27 (15%) | 58 (20%) | ||||

| Life stressors | No stressors | 12 (32%) | 87 (38%) | 0.84 | 33 (38%) | 67 (37%) | 0.20 | 44 (39%) | 63 (36%) | 0.79 | 107 (37%) |

| 1 stressor | 11 (29%) | 54 (24%) | 21 (24%) | 44 (24%) | 24 (21%) | 45 (25%) | 69 (24%) | ||||

| 2 stressors | 7 (18%) | 38 (17%) | 19 (22%) | 26 (14%) | 16 (14%) | 29 (16%) | 45 (16%) | ||||

| More than 2 stressors | 8 (21%) | 49 (21%) | 13 (15%) | 45 (25%) | 28 (25%) | 40 (23%) | 68 (24%) | ||||

| Caregiver with psychiatric condition | 5 (13%) | 29 (13%) | 1.00 | 14 (16%) | 20 (11%) | 0.24 | 14 (13%) | 22 (13%) | 1.00 | 36 (13%) | |

| Income more than $20,000/year | 18 (55%) | 106 (52%) | 0.85 | 41 (54%) | 83 (51%) | 0.68 | 40 (42%) | 94 (58%) | 0.01 | 134 (52%) | |

| Caregiver High School Graduate | 26 (68%) | 160 (70%) | 0.85 | 61 (72%) | 127 (69%) | 0.67 | 77 (68%) | 125 (71%) | 0.70 | 202 (70%) | |

| CD4 count | 0–199 cells/mm3 | 6 (16%) | 5 (2%) | 0.002 | 6 (7%) | 5 (3%) | 0.05 | 11 (10%) | 2 (1%) | <0.001 | 13 (4%) |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 7 (18%) | 45 (19%) | 22 (26%) | 30 (16%) | 36 (32%) | 28 (15%) | 64 (22%) | ||||

| 500–749 cells/mm3 | 11 (29%) | 73 (31%) | 21 (24%) | 65 (35%) | 36 (32%) | 54 (30%) | 90 (31%) | ||||

| 750–999 cells/mm3 | 4 (11%) | 54 (23%) | 14 (16%) | 44 (24%) | 13 (12%) | 47 (26%) | 60 (20%) | ||||

| 1000 cells/mm3 or more | 10 (26%) | 55 (24%) | 23 (27%) | 42 (23%) | 17 (15%) | 50 (28%) | 67 (23%) | ||||

| ARV Regimen | HAART with PI | 32 (84%) | 165 (71%) | 0.31 | 70 (81%) | 127 (68%) | 0.01 | 72 (64%) | 127 (70%) | <0.001 | 199 (68%) |

| HAART without PI | 3 (8%) | 43 (19%) | 6 (7%) | 40 (22%) | 10 (9%) | 38 (21%) | 48 (16%) | ||||

| 1–2 NRTIs | 0 (0%) | 10 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 6 (5%) | 4 (2%) | 10 (3%) | ||||

| 3 or more NRTIs | 2 (5%) | 10 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 8 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 5 (3%) | 12 (4%) | ||||

| Other combination therapy | 1 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (2%) | ||||

| Not on ARVs | - | - | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (15%) | 3 (2%) | 20 (7%) | ||||

| Any PI use prior to entry | 33 (87%) | 169 (73%) | 0.07 | 70 (81%) | 132 (71%) | 0.07 | 73 (66%) | 131 (72%) | 0.24 | 204 (70%) | |

| Any behavioral therapy prior to entry | 10 (26%) | 59 (26%) | 1.00 | 25 (29%) | 45 (25%) | 0.46 | 32 (29%) | 44 (25%) | 0.49 | 76 (26%) | |

| Psychotropic medication use | 5 (13%) | 33 (14%) | 1.00 | 14 (16%) | 26 (14%) | 0.71 | 8 (7%) | 32 (18%) | 0.01 | 40 (14%) | |

| Medication administration responsibility | Primary caregiver solely responsible | 9 (24%) | 82 (35%) | 0.27 | 26 (30%) | 65 (35%) | 0.14 | 29 (30%) | 62 (35%) | 0.51 | 91 (33%) |

| Subject solely responsible | 7 (18%) | 28 (12%) | 17 (20%) | 19 (10%) | 12 (12%) | 24 (14%) | 36 (13%) | ||||

| Subject and caregiver jointly | 22 (58%) | 115 (50%) | 42 (49%) | 96 (52%) | 52 (54%) | 86 (49%) | 138 (51%) | ||||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 7 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 7 (3%) | ||||

| Virological suppression (< 400copies/ml) | 21 (55%) | 154 (66%) | 0.20 | 50 (58%) | 125 (67%) | 0.17 | - | - | 181 (62%) | ||

PI= Protease Inhibitor; VL = Viral Load

Prevalence of non-adherence, lack of VL suppression, and psychiatric conditions

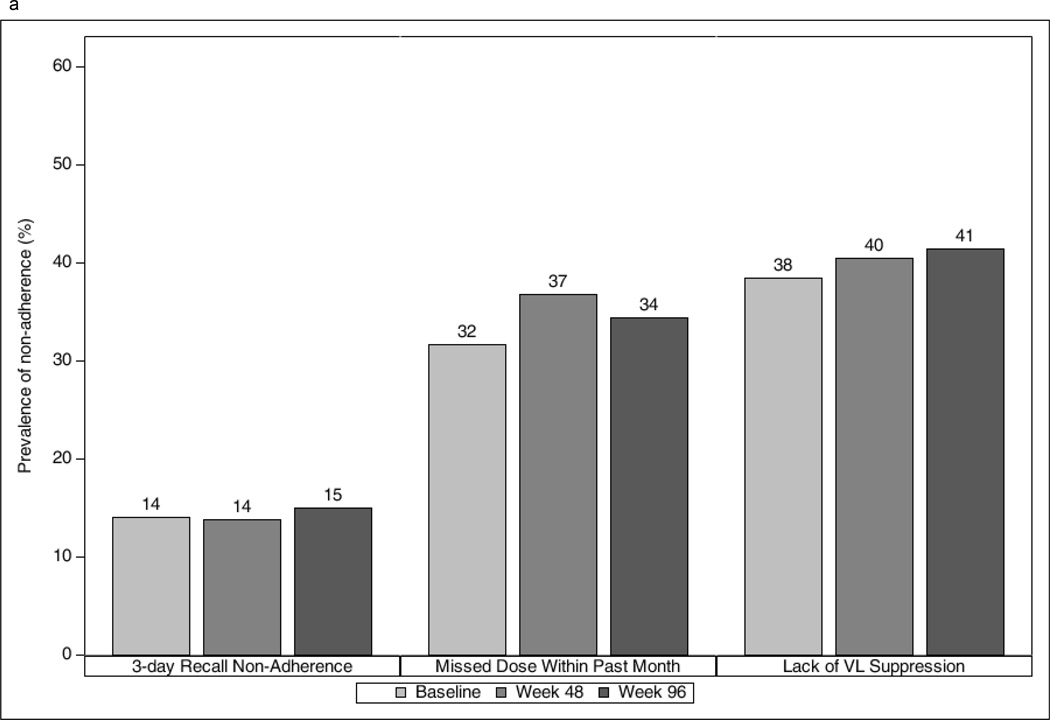

The prevalence of non-adherence at study entry was 14% by 3-day recall, 32% for past month non-adherence, and 38% based on unsuppressed VL; the prevalence for all three measures remained similar over time (Figure 1a). During study follow-up, 29% reported 3-day recall non-adherence, 54% reported past month non-adherence, and 54% had unsuppressed VL on at least one occasion. At follow-up, youth who were non-adherent by 3-day or past month recall were significantly more likely than adherent youth to have unsuppressed VL (e.g., for 3-day recall, 58% vs. 33%, p=0.01; 60% vs. 33%, p=0.007 for weeks 48 and 96, respectively), although differences did not attain significance at entry (e.g., for 3-day recall, 45% vs. 34%, p=0.20).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of non-adherence (a) and psychiatric conditions (b) by study week among youth in the IMPAACT P1055 study

At entry, 38% met symptom cutoffs for at least one of the targeted psychiatric conditions, 17% for ADHD, 13% for disruptive behavior, 14% for depression and 18% for anxiety (Figure 1b). Prevalence decreased at later visits for all conditions except for disruptive behavior.

Psychiatric conditions and non-adherence: GEE model results

Table 2 summarizes unadjusted and adjusted repeated measures logistic regression results for the association of each psychiatric condition and non-adherence, assuming associations remained similar over time. Throughout the study period, youth with anxiety symptoms had 40% lower odds of unsuppressed VL compared to youth without anxiety. No associations were observed between other psychiatric conditions and non-adherence or unsuppressed VL.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Repeated Measures GEE Models for Non-Adherence Assuming Constant Association Over Study Visit Weeks, IMPAACT P1055 Study, 2005–2008.

| Covariate | 3-day Recall Non-Adherence | Missed Dose Within Past Month | Lack of VL Suppression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Any Psychiatric Condition | 1.29 (0.81, 2.05) | 1.35 (0.85, 2.15) | 1.20 (0.88, 1.63) | 1.28 (0.92, 1.76) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 0.92 (0.69, 1.23) |

| ADHD | 1.50 (0.83, 2.72) | 1.48 (0.80, 2.75) | 1.35 (0.91, 1.99) | 1.31 (0.87, 1.97) | 1.24 (0.87, 1.75) | 1.10 (0.74, 1.62) |

| Disruptive Behavior | 1.70 (0.94, 3.08) | 1.65 (0.91, 3.00) | 1.36 (0.89, 2.08) | 1.27 (0.82, 1.98) | 1.03 (0.68, 1.56) | 0.83 (0.51, 1.36) |

| Depression | 1.23 (0.65, 2.35) | 1.31 (0.66, 2.57) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.95) | 1.46 (0.95, 2.26) | 0.93 (0.67, 1.29) | 0.94 (0.65, 1.37) |

| Anxiety | 0.89 (0.49, 1.62) | 1.05 (0.56, 1.96) | 0.66 (0.41, 1.07) | 0.78 (0.46, 1.33) | 0.65 (0.46, 0.92) | 0.60 (0.39, 0.93) |

Any Psychiatric Condition = ADHD; Disruptive Behavior; Depression; Anxiety.

GEE = Generalized Estimating Equation; OR = Odds Ratio; aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; VL = Viral Load.

ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; Disruptive Behavior = Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder; Depression = Major depression or Dysthymia; Anxiety = Separation or General Anxiety.

Separate models fit for each psychiatric condition and each outcome. Unadjusted models include psychiatric condition and visit week. Referent category is absence of the psychiatric condition.

Adjusted models all include age at entry, as well as the following covariates: 3-day recall - CD4 count at entry; Lack of VL suppression - race/ethnicity and income > $20,000/year.

Covariates independently associated with non-adherence in multivariable models (Table 3) included older age for all three non-adherence measures, and black race for unsuppressed VL, while lower odds of non-adherence were observed for those with higher entry CD4 count (for 3-day recall), and higher income (for unsuppressed VL). The associations with unsuppressed VL when restricted to youth with adherence information were similar to those of the full cohort. Sex was considered as a potential covariate for the core models but was not associated with any outcomes.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted GEE models: Other Covariates Associated with Non-Adherence. IMPAACT P1055 Study: 2005–2008

| Covariate | 3-day Recall Non-Adherence | Missed Dose Within Past Month | Lack of VL Suppression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 10–<13 (vs. 6–<10) | 2.01 (0.92, 4.42) | 2.00 (0.92, 4.37) | 2.22 (1.25, 3.96) | 2.28 (1.29, 4.04) | 1.82 (0.98, 3.40) | 1.52 (0.80, 2.90) |

| 13–<16 (vs. 6–<10) | 1.65 (0.77, 3.53) | 1.61 (0.76, 3.39) | 2.20 (1.26, 3.85) | 2.28 (1.32, 3.97) | 1.59 (0.86, 2.94) | 1.62 (0.84, 3.12) |

| 16–<18 (vs. 6–<10) | 2.86 (1.25, 6.56) | 2.49 (1.08, 5.72) | 3.46 (1.89, 6.35) | 3.53 (1.94, 6.44) | 3.12 (1.59, 6.15) | 3.70 (1.75, 7.81) |

| CD4 count ≥ 200 copies/mm3 (vs. < 200) | 0.29 (0.12, 0.69) | 0.35 (0.14, 0.85) | 0.41 (0.18, 0.94) | |||

| Any PI use prior to entry (vs. none) | 1.69 (0.97, 2.95) | 0.72 (0.46, 1.13) | ||||

| Income >$20,000/year (vs. ≤&20,000/year) | - | - | - | - | 0.56 (0.36, 0.87) | 0.58 (0.37, 0.92) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black (vs. White Non-Hispanic) | - | - | - | - | 2.70 (1.38, 5.30) | 2.74 (1.34, 5.58) |

| Hispanic (vs. White Non-Hispanic) | - | - | - | - | 2.42 (1.18, 4.97) | 2.11 (0.98, 4.55) |

GEE = Generalized Estimating Equation; OR = Odds Ratio; aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; PI = Protease Inhibitor; VL = Viral Load.

Unadjusted models include visit week and covariate of interest.

Adjusted models include “Any psychiatric condition,” visit week and adjust for all covariates associated with non-adherence with p-value < 0.2.

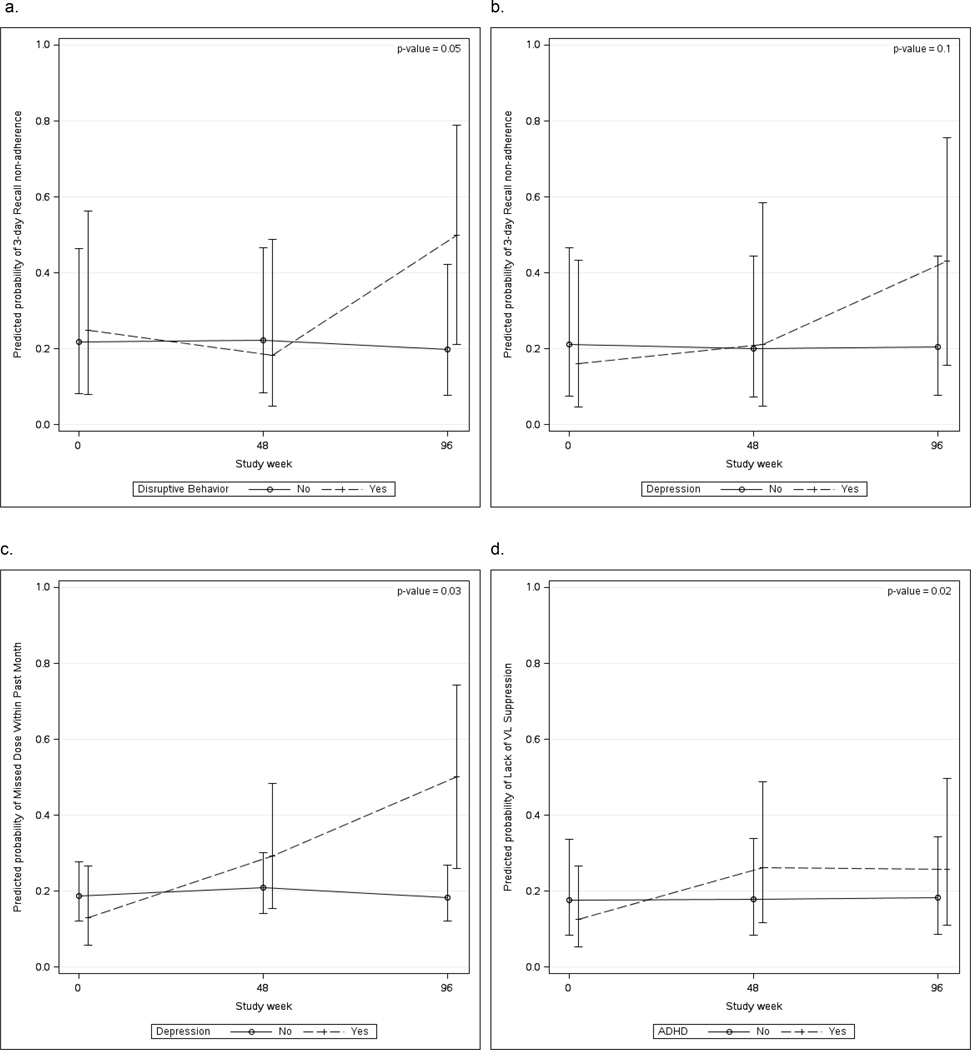

Figure 2 shows adjusted associations of each psychiatric condition with non-adherence at the three study time points when the assumption of a constant effect over time was not met (interaction p≤0.10). In models adjusting for age and CD4 count at entry, those with disruptive behavior conditions had greater odds of 3-day recall non-adherence at Week 96 (aOR=3.36; 95%CI: 1.02–11.10), but not at earlier visits (interaction p=0.05) (panel a). Youth with depression symptoms had greater odds of non-adherence at Week 96 for both 3-day recall (aOR=4.14; 95% CI: 1.11–15.42; interaction p= 0.10) and past month non-adherence (aOR= 6.96; 95% CI: 1.60–30.29; interaction p=0.03) but not earlier (panels b and c). Odds of unsuppressed VL were greater for youth with versus without ADHD (panel d) at Weeks 48 (aOR=2.46; 95% CI: 1.27–4.78) and 96 (aOR=2.35; 95% CI: 1.01–5.45) vs. entry (interaction p=0.02).

Figure 2.

Adjusted predicted probabilities (with 95% confidence intervals) of 3-day recall non-adherence in youth with vs. without disruptive behavior (a), 3-day recall non-adherence in youth with vs. without depression (b), Missed dose within the past month in youth with vs. without depression (c), and unsuppressed viral load among youth with vs. without ADHD (d).

Psychiatric conditions and incident non-adherence and loss of VL suppression

Among 232 youth who were adherent at entry by 3-day recall, 39 (16%) were non-adherent by 3-day recall at follow-up. Youth with disruptive behavior conditions at entry were more likely than those without to become non-adherent by 3-day recall during follow-up (34% vs. 14%, p=0.014); this association persisted after adjustment (aOR=3.01; 95%CI: 1.24–7.31). We observed no significant associations between the other measures of psychiatric conditions at entry and incident non-adherence. Among youth who were adherent in the past month at entry, 33% reported later non-adherence. Twenty-five percent of virologically suppressed youth at entry experienced loss of virologic suppression at later visits. Psychiatric conditions at entry were not associated with development of past month non-adherence or with loss of virologic suppression at follow-up.

DISCUSSION

In this study, youth with PHIV who had depression or disruptive behavior symptoms had greater odds of ARV non-adherence at later visits but not at entry. Youth with ADHD had greater odds of unsuppressed VL than youth without ADHD symptoms at later visits but not at entry. Conversely, youth with anxiety had lower odds of unsuppressed VL compared to youth without anxiety. Although no single psychiatric condition was consistently associated with all three outcomes, observed associations underscore the need for greater clinical attention to prevalent and developing psychiatric conditions to improve adherence and reduce the risk of virologic failure and other adverse HIV disease outcomes as youth with PHIV approach adulthood.

Self-reported non-adherence ranged from 14–32% at entry, depending on the measure, and remained similar over time. These estimates are within the 16%–60% range found in other studies of US youth with HIV [15, 28–30]. Nearly one in three youth in our study reported past month non-adherence, but fewer were non-adherent by 3-day recall, similar to studies showing lower non-adherence estimates with shorter recall periods [15, 30, 31].

There are several potential explanations for associations with non-adherence that we observed at later visits for depression and disruptive behavior, and associations with unsuppressed VL at later visits for ADHD but not at entry. As youth become older, the potential deleterious impact of a psychiatric condition on non-adherence may become more acute when adherence to ARV must be managed in the context of other stressors emerging in late adolescence, including challenges faced at school, stigma, disclosure of HIV status to peers, and loss of friends and family members to HIV/AIDS. Risk of non-adherence could also be different for youth developing incident psychiatric conditions at later vs. earlier time points. A previous study from our cohort showed that 22% of youth with PHIV who did not meet symptom cutoff criteria at entry had an incident psychiatric condition during follow-up [8]. The validated rating scales we used to assess psychiatric conditions capture those meeting symptom cutoffs, but were not administered frequently enough to assess short-term fluctuations in psychiatric condition severity nor do they consider changes in psychiatric treatment over time, each of which could be associated with non-adherence. For ADHD, one review noted that youth with ADHD were more likely than those without to discontinue medication and skip appointments in later adolescence [32]. It is possible that the association between ADHD and lack of VL suppression but not self-reported non-adherence is due to discontinuation of or breaks in medication use at later rather than earlier visits, which are not captured in our self-reported adherence measures.

In contrast to other psychiatric conditions examined, youth with anxiety had reduced odds of unsuppressed VL over two years. Although this finding is counter to a prior study showing that PHIV youth with anxiety had marginally poorer adherence [15], one study of adults found that presence of anxiety symptoms predicted adherence [33]; another longitudinal study of pediatric renal and liver transplant recipients showed that anxiety was associated with adherence to immunosuppressive medication [34]. Youth with anxiety may be more vigilant about taking medications, which could lead to VL suppression. However, our study did not show associations between anxiety and self-reported measures of adherence, which may be due to insufficient statistical power to detect differences in adherence.

Adherence and VL suppression are highly dynamic, as demonstrated among adults with HIV [18,35]. Twenty-five percent of youth with VL suppression at entry experienced a loss of VL suppression over two years, and up to one third of youth who were adherent at entry became non-adherent at follow-up, highlighting the need for tools to support adherence and retention in care over time. Adherent youth with disruptive behavior conditions had 3-fold greater odds of becoming non-adherent over a two year period compared to adherent youth without those conditions. A large cross-sectional study of US youth with PHIV similarly found that youth with conduct problems or general hyperactivity had elevated odds of non- adherence [12]. Engaging and supporting parents and caregivers in management of their children’s disruptive behavior conditions, in partnership with mental health and HIV care providers, may be warranted for promoting mental health and ARV adherence among youth with these comorbid conditions. Other disorders were not associated with incident non-adherence or loss of VL suppression in our study possibly due to psychiatric conditions being dynamic over time, particularly during adolescence [36]. Studies in larger samples should determine whether changes in psychiatric condition status are associated with changes in adherence or VL suppression. Notably, despite a lifetime of HIV disease, two-thirds of adherent youth consistently reported adherence over two years, and 75% of suppressed youth were consistently virologically suppressed. Identifying resiliency factors enabling youth to maintain adherence is vital to creating strategies to support adherence [6, 37–40].

Older age was an important predictor of non-adherence in our study, consistent with prior research [15,41–42]. Older age may indicate longer illness duration, medication fatigue from years of ARV exposure or accumulated ARV resistance [43]. Additionally, adolescents start assuming responsibility for their ARVs and are also more likely to be reporting on their psychiatric condition symptoms and adherence. Adolescent development poses challenges to adherence. As many youth learn their HIV status during identity formation, some may face struggles with how to incorporate HIV disease [44]. Non-adherence may be a way older adolescents assert independence from parents, clinicians, and other authority figures. Youths’ efforts to fit in with their peers may include hiding their HIV disease, which may impede adherence [45]. Psychiatric condition symptoms further complicate developmental processes. Additionally, being black and having lower income were each associated with unsuppressed VL over two years but not with self-reported non-adherence. Racial and economic disparities in virologic and immunologic outcomes and survival have been observed in US adults with HIV [46] but the underlying mechanisms are less well described. Stress, violence, experiences of discrimination, lower access to or lower quality care, and distrust in the medical system all may contribute to racial and economic disparities we observed [47].

This study had limitations. Non-adherence and psychiatric symptoms were assessed through self-report and may be underreported due to social desirability bias or stigma. To mitigate this we obtained psychiatric condition data via self-administered questionnaires and combined caregiver and participant reports. Youth adherence was reported by either the youth or caregiver. Although prior research has shown reporting discrepancies [48], associations of psychiatric conditions with non-adherence held in sensitivity analyses adjusting for adherence reporter. The past-month non-adherence measure referred to any medication, precluding the possibility of distinguishing adherence to psychotropic medications from ARVs, which may have resulted in misclassification. Results from this clinic-based sample may not be generalizable to youth with less adequate access to or engagement in medical care. Nevertheless, an important strength is that it is the first study to our knowledge to assess relationships between psychiatric conditions and non-adherence in youth with PHIV longitudinally across multiple outcomes and psychiatric conditions using well-validated measures.

Results from this study have implications for research and care of youth with PHIV: Ongoing screening for psychiatric conditions and ARV adherence challenges is essential throughout adolescence and young adulthood. Adherence interventions should address existing and emerging psychiatric comorbidities and their treatment. More research on multifaceted adolescent-friendly clinical- family- and community-based models of care like the Collaborative HIV/AIDS Mental Health Program (CHAMP+) [39], which jointly promote mental health and antiretroviral adherence while strengthening family factors is needed. Our results underscore the need for comprehensive, age-appropriate adherence interventions that promote mental health throughout the transition to adult HIV care. Future research should determine the impact of psychotropic and counseling treatment for current and emerging psychiatric conditions on adherence and VL suppression as these youth enter young adulthood. As more youth with PHIV in developing countries approach adulthood, longitudinal studies are warranted to examine whether these results are applicable globally.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Source of Funding: K.D. Gadow is shareholder in Checkmate Plus, publisher of the Symptom Inventories. Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [U01 AI068632] and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI-41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI-068616 with the IMPAACT Group.

We would like to thank Kimberly Hudgens for her operational support of this study and Janice Hodge for data management. In addition to their contributions to the manuscript, we would like to acknowledge the help given by Nagamah Sandra Deygoo in representing the site research staff on the protocol team and Vinnie Di Paolo for representing the community affected by HIV.

Appendix

The following institutions and individuals participated in IMPAACT P1055:

Children’s Hospital Boston: Sandra Burchett; UCLA-Los Angeles AIDS Consortium: Karin Nielsen, Nicole Falgout, Joseph Geffen, Jaime Deville; Long Beach Memorial Medical Center: Audra Deveikis; UCLA Medical Center: Margaret Keller; University of Maryland Medical Center: Vicki Tepper; Chicago Children’s CRS: Ram Yogev; UCSF Pediatric AIDS CRS: Diane Wara; UCSD Maternal Child and Adolescent HIV CRS: Stephen Spector, Lisa Stangl, Mary Caffery, Rolando Viani; Duke University Medical Center: Kreema Whitfield, Sunita Patil, Joan Wilson, Mary Jo Hassett, New York University School of Medicine: Sandra Deygoo, William Borkowsky, Sulachni Chandwani, Mona Rigaud; Jacobi Medical Center: Andrew Wiznia; Univ. of Washington Children’s Hosp. Seattle: Lisa Frenkel; USF Tampa: Patricia Emmanuel, Jorge Lujan Zilberman, Carina Rodriguez, Carolyn Graisber; Mt Sinai School of Medicine: Roberto Posada, Mary Dolan; San Juan City Hospital: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Lourdes Angeli, Milagros Gonzalez, Dalila Guzman; Yale University School of Medicine: Warren Andiman, Leslie Hurst, Anne Murphy; SUNY Upstate Medical University: Leonard Weiner; SUNY Stony Brook: Denise Ferraro, Michele Kelly, Lorraine Rubino; Howard University: Sohail Rana; University of Southern California: Suad Kapetanovic; University of Florida Jacksonville: Mobeen Rathore, Ayesha Mirza, Kathleen Thoma, Chas Griggs; University of Colorado: Robin McEvoy, Emily Barr, Suzanne Paul, Patricia Michalek; South Florida Center for Diagnostic Care: Ana Puga; St Jude: Patricia Garvie; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Richard Rutstein; St Christopher’s Hospital for Children: Roberta LaGuerre; Bronx-Lebanon Hospital: Murli Purswani; Metropolitan Hospital Center: Mahrukh Bamji; WNE Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS: Katherine Luzuriaga.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: For the remaining authors none were declared.

Author Contributions: DK, KA, MC, and PLW conceived the analysis. KA conducted the statistical analysis. SN, KDG, PLW and MC conceived of and directed the IMPAACT P1055 study. DK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation and scientific direction of statistical analyses, revisions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among youth. [Accessed 05/09/2014]; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/youth/index.html?s_cid=tw_drdeancdc-00125#C.

- 3.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [PMCID 10877736] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [PMCID 10877736] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tassiopoulos K, Moscicki AM, Mellins C, Kacanek D, Malee K, Allison S, et al. Sexual risk behavior among youth with perinatal HIV infection in the United States: predictors and implications for intervention development. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(2):283–290. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18593. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Bouwers P, Morse E, Heston J, et al. Co-occuring psychiatric symptoms in children perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(2):116–128. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cdaa20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadow KD, Angelidou K, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Heston J, Hodge J, Nachman S. Longitudinal study of emerging mental health concerns in youth perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparisons. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(6):456–468. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31825b8482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu CS, Elkington KS, Dolezal C, Wiznia A. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Leu CS, Santamaria EK, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, et al. Prevalence and change in psychiatric disorders among perinatally HIV infected and HIV-exposed youth. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):953–962. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, Moscicki AB, Patton D, Smith R, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(7):413–422. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malee K, Williams P, Montepiedra G, McCabe M, Nichols S, Sirois PA, et al. Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV infection: associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [PMCID: 21323533]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy DA, Belzer M, Durako SJ, Sarr M, Wilson CM, Muenz LR for the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS research Network. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(8):764–770. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walkup J, Akincigil A, Bilder S, Rosato NS, Crystal S. Psychiatric diagnosis and antiretroviral adherence among adolescent Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with Human Immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2009;197(5):354–361. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a208af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Kammerer B, Sirois PA, et al. PACTG 219C Team. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1745–1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [PMCID 17101712] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapetanovic S, Wiegand RE, Dominguez K, Blumberg D, Bohannon B, Wheeling J, et al. Associations of medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and risky health behaviors in highly active antiretroviral therapy experienced perinatally HIV-infected youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(8):493–501. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naar-King S, Montepiedra G, Garvie P, Kammerer B, Malee K, Sirois PA, et al. Social ecological predictors of longitudinal HIV treatment adherence in youth with perinatally acquired HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, Leport C, Raffi F, Moatti JP APROCO Cohort Study Group. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: from a predictive to a dynamic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1481–1496. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibb DM, Goodall RL, Giacomet V, McGee L, Compagnucci A, Lyall H for the Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS Steering Committee. Adherence to prescribed antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in the PENTA 5 trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:56–62. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, Brouwers P, Heston J, Hodge J, et al. Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV-infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):627–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachman S, Chernoff M, Williams P, Hodge J, Heston J, Gadow KD. Human Immunodeficiency Virus severity, psychiatric symptoms and functional outcomes in perinatally infected youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):528–535. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams PL, Chernoff M, Angelidou K, Brouwers P, Kacanek D, Deygoo NS, et al. Participation and retention of youth with perinatal HIV infection in mental health research studies: the IMPAACT P1055 psychiatric comorbidity study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):401–409. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318293ad53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R. Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Youth’s Inventory 4 Manual. Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson GA, et al. A DSM-IV referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):671–679. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Self Report Inventory-4. Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simoni JM, Montgomery A, Martin E, New M, Demas PA, Rana S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: a qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1371–e1383. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig LJ, Nesheim S, Abramowitz S. Adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV: emerging behavioral and health needs for long-term survivors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:321–327. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834a581b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandwani S, Koenig LJ, Sil A, Abromowitz S, Conner LC, D’Angelo L. Predictors of medication adherence among a diverse cohort of adolescents with HIV. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson IB, Carter AE, Berg KM. Improving the self-report of HIV antiretroviral medication adherence: Is the glass half full or half empty? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6(4):177–186. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0024-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolraich ML, Wibbelsman CJ, Brown TE, Evans SW, Gottlieb EM, Knight JR, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents: A review of the diagnosis, treatment and clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1734–1746. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingersol K. The impact of psychiatric symptoms, drug use and medication regimen on non-adherence to HIV treatment. AIDS Care. 2004;16(2):199–211. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu YP, Aylward BS, Steele RG. Associations between internalizing symptoms and trajectories of medication adherence among pediatric renal and liver transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(9):1016–1027. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB. Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: A longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Health Living (NFHL) study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(2):266–272. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b720e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow A, Hansen N. Annual research review: Mental health and resilience in HIV/AIDS-affected children:a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;54(4):423–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amzel A, Toska E, Lovich R, Widyono M, Patel T, Foti C, et al. Promoting a combination approach to paediatric HIV psychosocial support. AIDS. 2013;27(suppl 2):S147–S157. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKay MM, Block M, Mellins C, Traube DE, Brackis-Cott E, Minott D, et al. Adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for HIV infected preadolescents and their families. Youth, families and health care providers coming together to address complex needs. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5(3):355–378. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n03_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, Siberry G, Williams PL, Hazra R, et al. Mental health functioning among children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1533–1534. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.575120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunologic outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in Southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;41(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199072e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agwu AL, Fleishman JA, Rutstein R, Korthuis PT, Gebo K. Changes in advanced immunosuppression and detectable HIV viremia among perinatally HIV-infected youth in the multisite United States HIV research network. J of Pediatric Infectious Disease Soc. 2013;2(3):215–223. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pit008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hazra R, Siberry GK, Mofenson LM. Growing up with HIV: children, adolescents and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:169–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.050108.151127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Persson A, Newman CE, Miller A. Caring for ‘underground’kids:qualitative interviews with clinicians about key issues for young people growing up with perinatally acquired HIV in Australia. [accessed 3/6/15];International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2014 www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02673843.2013.866149. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taddeo D, Egedy M, Frappier J. Adherence to treatment in adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13(1):19–24. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ribaudo HJ, Smith KY, Robbins GK, Flexner C, Haubrich R, Chen Y, et al. Racial difference in response to antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: an AIDS clinical trials group (ACTG) study analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;15(11):1607–1617. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ. Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0397-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolezal C, Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Abrams EJ. The reliability of reports of medical adherence from children with HIV and their adult caregivers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:355–361. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]