To The Editor

Among adults seeking care with sore throat, the prevalence of Group A streptococci (GAS) – the only common cause of sore throat requiring antibiotics – is about 10%.1 Penicillin remains the antibiotic of choice. Penicillin is narrow-spectrum, well-tolerated, inexpensive, and GAS is universally susceptible to penicillin.

We previously found that the antibiotic prescribing rate for adults making a visit with sore throat dropped from about 80% to 70% around 1993.2 Since then, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others have continued efforts to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.3–5 To measure changes in antibiotic prescribing for adults with sore throat, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis of ambulatory visits in the United States.

Methods

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) are annual, multi-stage probability, nationally representative surveys of ambulatory care in the United States.6 The NAMCS/NHAMCS collect information on physicians and practices, as well as visit-level data including patient demographics, reasons for visits, diagnoses, and medications. Each visit in the NAMCS/NHAMCS is weighted to allow extrapolation to national estimates.

For the years 1997–2010, we included “new problem” visits by adults 18 years and older with a primary reason for visit of throat soreness/pain (Reason for Visit code 1455) who made a primary care or emergency department (ED) visit. We excluded patients with injuries, immunosuppression, or concomitant infectious diagnoses. There were 8191 sampled sore throat visits meeting these criteria. We identified and classified antibiotics as penicillin, amoxicillin, erythromycin, azithromycin, other 2nd line antibiotics, and all other antibiotics.

We calculated standard errors for all results using the survey package in R, version 2.11.1 (Vienna, Austria). We combined data into 2-year periods. We clearly indicate when estimates are below the threshold of reliable measurement (< 30 sampled visits or a relative standard error of >30%).

Results

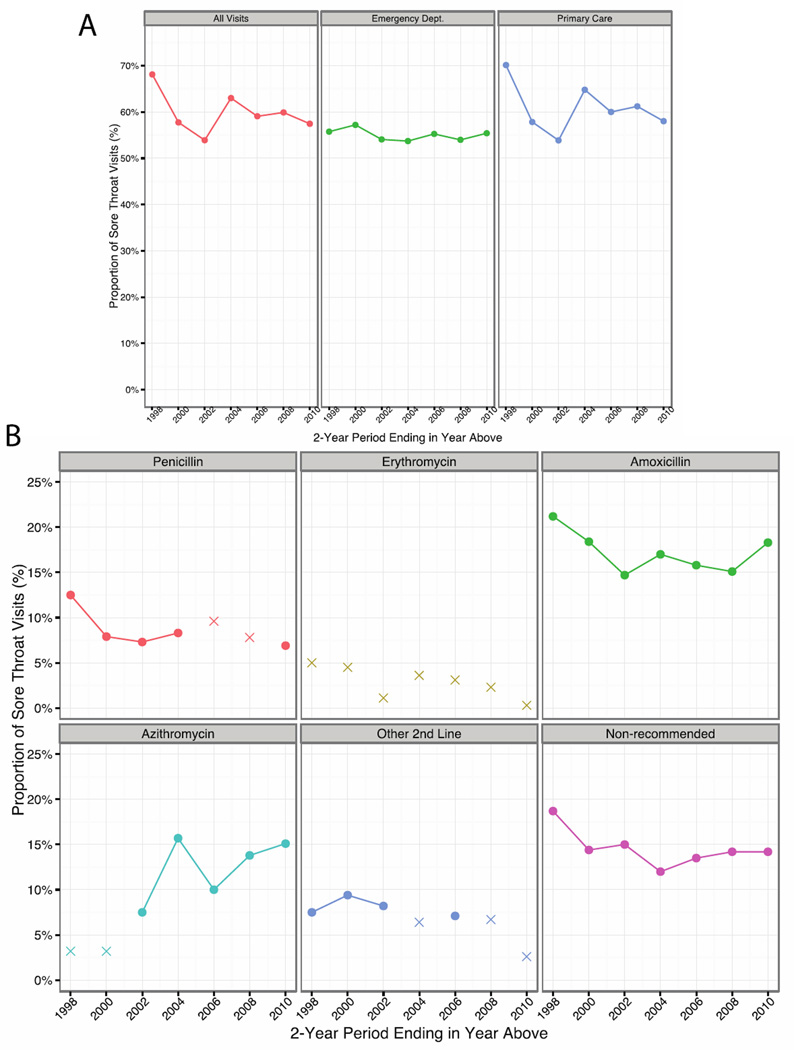

Between 1997 and 2010, the 8191 sampled sore throat visits represented 92 million estimated visits by adults to primary care practices and EDs in the United States (Table). Sore throat visits decreased from 7.5% of primary care visits in 1997 to 4.3% of visits in 2010 (p = 0.006). There was no change in the proportion of sore throat visits to EDs: 2.2% in 1997 and 2.3% in 2010 (p = 0.18). Physicians prescribed antibiotics at 60% (95% confidence interval, 57% to 63%) of visits. The overall national antibiotic prescribing rate did not change (Figure). Penicillin prescribing remained stable at 9% of visits. Azithromycin prescribing increased from below the threshold of reliable measurement in 1997–1998 to 15% of visits in 2009–2010.

Table.

Visit Characteristics and Prescribing of Antibiotics to Adults with Sore Throat in the United States, 1997–2010

| Visits (n = 8191*) | Antibiotic Prescribing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion, % | % Receiving† | P Value‡ | |

| Patient Age, years | 0.005 | ||

| 18–44 | 71% | 63% | |

| 45–64 | 22% | 55% | |

| 65+ | 7% | 47% | |

| Gender | 0.001 | ||

| Women | 65% | 57% | |

| Men | 35% | 66% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.45 | ||

| White | 84% | 60% | |

| Black | 11% | 60% | |

| Other | 5% | 52% | |

| Insurance | 0.001 | ||

| Private | 65% | 60% | |

| Medicare | 7% | 57% | |

| Medicaid | 9% | 47% | |

| Self-pay/other§ | 19% | 66% | |

| Specialty/Setting | 0.003 | ||

| Primary Care | 82% | 61% | |

| Emergency Dept. | 18% | 55% | |

| Region | 0.04 | ||

| Northeast | 20% | 57% | |

| Midwest | 27% | 62% | |

| South | 35% | 64% | |

| West | 18% | 53% | |

| Rural/Urban | 0.98 | ||

| Rural | 17% | 60% | |

| Urban | 83% | 60% | |

N = 8,191 sampled sore throat visits representing 92 million (95% CI, 85 to 100 million) estimated sore throat visits.

% receiving is the proportion of patients with sore throat in each category (row percent) who received any antibiotic.

Pearson’s chi-squared test.

Self-pay/other insurance was self-pay (66% of category), missing (18%), and other (14%).

Figure.

A, Antibiotic prescribing for all sore throats, primary care practices, and emergency departments. P values for linear trend were 0.31 for all sore throat visits, 0.35 for primary care physicians, and 0.75 for emergency departments. B, Antibiotic prescribing by antibiotic class. “Xs” represent estimates that are below the threshold of reliable measurement. Other 2nd-line antibiotics were first-generation cephalosporins, clarithromycin, and clindamycin. The most commonly prescribed non-recommended antibiotics were cephalosporins (37% of category), penicillin/beta-lactamase combinations (27%), and fluoroquinolones (13%). P values for trend were 0.27 for penicillin, <0.001 for azithromycin, 0.33 for amoxicillin, and 0.37 for non-recommended antibiotics.

Discussion

Our analysis has limitations. First, we do not have clinical data to know if individual antibiotic prescriptions are appropriate. Second, the NAMCS/NHAMCS does not capture patients managed outside of clinic or ED visits. Third, several of our 2-year estimates were below the threshold of reliable measurement.

Antibiotic prescribing to patients who are unlikely to benefit is not benign. All antibiotic prescribing increases the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The financial cost of unnecessary antibiotic prescribing to adults with sore throat in the United States from 1997–2010 was conservatively $500 million. However, antibiotics could have been up to 40-times more expensive. For individuals, antibiotic prescribing leads to 5% to 25% of patients developing diarrhea; at least 1 in 1000 patients visit an emergency department for a serious adverse drug event.

In conclusion, despite decades of effort, we found only incremental improvement in antibiotic prescribing for adults making a visit with sore throat. Combining our previous and present analyses, the antibiotic prescribing rate dropped from roughly 80% to 70% around 1993 and dropped again around 2000 to 60%, where it has remained stable.2 This still far exceeds the 10% prevalence of GAS among adults seeking care for sore throat. The prescription of broader-spectrum, more expensive antibiotics, especially azithromycin, was common. Prescribing of penicillin, which is guideline-recommended, inexpensive, well-tolerated, and to which GAS is universally susceptible, remained infrequent.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Barnett consults as a medical advisor to a start-up, Ginger.io, which has no relationship to this research.

Support and Role of Sponsors: Dr. Linder’s work on acute respiratory infections is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RC4 AG039115), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21 AI097759), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R18 HS018419). No sponsor had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Linder has no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Data Access and Responsibility: Dr. Barnett had full access to all the data in the study, which is publically available, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The NCHS institutional review board approved the protocols for the NAMCS/NHAMCS, including a waiver of the requirement for patient informed consent.

Prior Presentation: Presented in part at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, April 25, 2013, Denver, CO. To be presented in part at IDWeek, October 4, 2013, San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Wessels MR. Clinical practice. Streptococcal pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(7):648–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1009126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder JA, Stafford RS. Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: a national survey, 1989–1999. JAMA. 2001;286(10):1181–1186. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work. [Accessed August 13, 2013]; http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/.

- 4.Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):509–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1279–1282. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Care Surveys. [Accessed August 9, 2013]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs.htm.