Abstract

African Americans face disproportionate sexually transmitted infection including HIV (STI/HIV), with those passing through a correctional facility at heightened risk. There is a need to identify modifiable STI/HIV risk factors among incarcerated African Americans. Project DISRUPT is a cohort study of incarcerated African American men recruited from September 2011 through January 2014 from prisons in North Carolina who were in committed partnerships with women at prison entry (N=207). During the baseline (in-prison) study visit, participants responded to a risk behavior survey and provided a urine specimen, which was tested for STIs. Substantial proportions reported multiple partnerships (42%), concurrent partnerships (33%), and buying sex (11%) in the six months before incarceration, and 9% tested positive for an STI at baseline (chlamydia: 5.3%, gonorrhea: 0.5%, trichomoniasis: 4.9%). Poverty and depression appeared to be strongly associated with sexual risk behaviors. Substance use was linked to prevalent STI, with binge drinking the strongest independent risk factor (adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 3.79, 95% CI: 1.19–12.04). There is a continued need for improved prison-based STI testing, treatment, and prevention education as well as mental health and substance use diagnosis.

Keywords: Incarceration, STI, HIV, Committed Partnerships, Poverty, Substance Use, Mental Illness

INTRODUCTION

Though African Americans represent 13% of the US population, they account for nearly half of persons living with HIV/AIDS (1, 2) and, compared with whites, face eight to 18 times the incidence of common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis (3). There also are marked racial disparities in incarceration in the US (4), due in part to the War on Drugs, racial bias in arrests and sentencing, and other structural factors (5). The disproportionate incarceration of African American men, in part through its disruption of sexual networks, is hypothesized to play an important role in the race disparity in STI/HIV (6, 7). Heterosexual African Americans with a history of incarceration are six times more likely to be HIV-infected than those with no incarceration history (8); substantial proportions of HIV-infected African Americans pass through a correctional facility annually (9), and other STIs are likewise high among inmates in prisons and jails (10). Further, studies across numerous populations, including in predominantly African American samples, suggest a history of incarceration is a strong and consistent independent risk factor for sexual risk behavior and STI/HIV (11–14). While the structural violence of mass incarceration is likely an important driver of STI/HIV risk among African Americans, other modifiable factors that increase risk for infection among African Americans involved in the criminal justice system also are likely to play an important role.

We currently are conducting Project DISRUPT (Disruption of Intimate Stable Relationships Unique to the Prison Term), a cohort study of HIV-negative African American men incarcerated in the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) who were in committed intimate partnerships with women at the time of incarceration and who were soon to be released to the community. There is a continued need to identify the factors driving STI/HIV in the Deep South, an important epicenter of the US HIV and STI epidemics (15–17). The study has a focus on heterosexual partnerships given the relative lack of research on STI/HIV risk among heterosexual African American men and because our pilot work indicated the majority of inmates were in committed partnerships with women (18). This project ultimately will assess the degree to which incarceration-related relationship disruption increases STI/HIV risk among former inmates during community re-entry.

DISRUPT pilot work suggested that three factors – poverty, mental illness, and substance use – may contribute to STI/HIV risk among men in the criminal justice system in part by interacting with incarceration to disrupt and dissolve the committed partnerships that protect against multiple partnerships and sex trade (18, 19). Research conducted by other groups also has suggested that each of these factors may contribute to STI/HIV risk behaviors and infection, including among individuals involved in the criminal justice system. First, poverty may increase STI/HIV risk by destabilizing partnerships, leading to initiation of new partnerships (6). The increased psychological distress associated with poverty can contribute to substance use (20–36), a consistent correlate of STI and related behaviors (37–40). While there is evidence that poverty is linked to STI/HIV risk among men involved in the criminal justice system (41, 42), research on the association among inmates is relatively limited despite high levels of poverty observed among inmates (43). Mood disorders also are risk factors for sexual risk behavior and infection (44–48). Depression may decrease impulse control (49, 50) or contribute to psychosocial impairment and reactivity in relationships (51, 52), while anxiety may increase avoidant coping strategies (48). Adverse psychosocial effects of these disorders may contribute to engagement in sexual risk-taking (48), substance use (20–36), and infection (37–39). Research on the role of depression and anxiety in the STI/HIV risk among inmates is extremely limited and no prior study to our knowledge has examined depression and anxiety and STI/HIV risk among incarcerated African American men. Such research is warranted because associations between depression and STI appear to be particularly robust among general population African American men compared with other racial/ethnic sub-groups (45). Finally, when investigating STI/HIV among incarcerated populations, consideration of substance use as a factor underlying infection risk is critical given substantial proportions of the US prison population report a history of heavy drug and alcohol use (53), and substance use is associated with sexual risk behaviors and infection in numerous populations including among prison inmates (37, 39,41, 54). No study has been conducted to measure the association between substance use and STI/HIV risk behavior and infection among African American men involved in the criminal justice system. The current study calls for improved substance use treatment as a means of addressing STI/HIV risk in the prison system are welcome (55); such programming would be improved by greater understanding of the most commonly used substances and the substances most strongly linked to risk within sub-groups of inmates.

In the current paper, we describe poverty, mood disorder, and substance use correlates of STI/HIV risk outcomes in a sample of Project DISRUPT cohort participants: incarcerated African American men in committed partnerships with women at the time of incarceration. Improved understanding of the factors that may contribute to risk among incarcerated men in committed partnerships is critical to designing community- and correctional facility-based STI/HIV risk reduction programs for couples affected by incarceration. Using data from the baseline (in-prison) study visit, the aim of this study was to describe cross-sectional associations between poverty, mood disorders, and substance use and STI/HIV risk outcomes including sexual risk behaviors and prevalent chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis. STIs constitute a clear public health concern given they are highly prevalent and underdiagnosed (56), result in considerable morbidity (57), and increase HIV transmission risk (58, 59).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of New York University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, and the University of Florida.

Recruitment and Population

Participants were recruited from September 2011 through January 2014 from minimum and medium security facilities of the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS). Participants were screened in two stages (pre-screening based on review of administrative databases and in-person screening). Pre-screening criteria were those that could be identified by review of administrative lists generated by the NCDPS database: African American; male; at least 18 years old; scheduled to be released from an eligible NCDPS prison within 2 months of recruitment; incarcerated for <36 months; HIV-negative based on HIV testing at prison intake; not currently incarcerated for forcible rape, murder 1, murder 2, or kidnapping; and not held in segregation at the time of recruitment. Among those who met pre-screening criteria, DISRUPT study staff screened interested inmates for further eligibility criteria at recruitment facilities. The study team worked closely with each facility to develop appropriate recruitment and screening procedures. Facility staff called pre-7 screened inmates to a private location at the facility, such as an office or a classroom, and informed him about the opportunity to be screened for potential participation in a study. Those who were interested met a study staff member who explained the study goals. Those interested in being screened were administered an eligibility questionnaire that assessed the following criteria: in a committed intimate partnership with a woman at the time of prison entry; lived free in the community for ≥6 months prior to the current incarceration with the exception of incarcerations of less than one month; able to communicate in English; willing to provide informed consent and post-release contact information. To assess involvement in a committed intimate partnership with a woman at the time of incarceration during screening we asked: “I want you to think back to when you left the community to begin this incarceration. At that time, were you in a committed intimate relationship with a woman? That is, was there a woman in your life who you were having sex with regularly and who you felt committed to-- someone who was an important part of your day to day life. This might include, but is not limited to, someone like a wife, a girlfriend, someone who you were living with, or someone who you saw every day or almost every day.” Men who had a committed partnership with a man but not a woman were screened out, while men in a committed partnership with a woman who also had a committed partnership with a man were considered eligible. Men were asked if they had one committed partner or more than one committed partner. Men who reported at least one committed female partner were eligible even if they had other male or female sex partners in the six months before incarceration (e.g., eligible participants did not need to report monogamy or sex with women only). Those who were eligible and interested in study participation were enrolled.

We initially restricted recruitment to inmates who reported the intention to return to communities within approximately 100 miles of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where the research data collection site was based. However, to increase enrollment, mid-way through the study we expanded recruitment to all inmates who were otherwise eligible by offering to conduct follow-up interviews by phone for those returning to locations outside the 100 mile radius.

Baseline Study Visit Procedures

At the baseline study visit, usually held immediately after recruitment, participants responded to a computer-assisted survey that assessed participants’ individual and relationship characteristics. The survey started with a face-to-face component but the vast majority of the survey employed audio computer-assisted self-interview software. Each interview took approximately 90 to 120 minutes to complete. All interviews were held in a private room in the NCDPS. Study staff were available at all times during the visit to answer participants' questions, provide assistance, and/or respond to participants’ concerns.

At the end of the baseline visit, participants provided urine specimens (20–30 mL of the first stream) to test for STIs not routinely assessed in prison (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis). Within 48 hours of confirmed positive STI results, DISRUPT staff notified facility medical staff who facilitated treatment of positives and notified the NC Department of Health of chlamydia and gonorrhea cases. Participants were informed at enrollment that positive results would be reported to the NC Department of Health.

Per prison policy, participants were not reimbursed for in-prison research activities. Participants were informed they would be reimbursed $50 for each of the three post-release follow-up visits and $50 for participation in all study-related phone calls (to schedule/remind of study visit appointments, to update contact information). Hence at baseline participants were informed of the possibility of being reimbursed up to $200 for cohort study participation.

Measures

STI/HIV Risk Behaviors and Infection

Sexual Risk Behaviors

We defined female sex partners as women with whom the participant had ever had vaginal or anal sex. Male partners were men with whom the participant had ever had anal sex. We assessed the following sexual risk behaviors in the six months before incarceration: multiple partnerships, defined as having more than one sexual partnership; concurrent partnerships defined as having one sex partner during the same time period the participant was having sex with someone else; sex without a condom with a new or casual female sex partner; buying sex from female and/or male partners, defined as giving money, drugs, or a place stay in exchange for sex; and selling sex to female and/or male partners defined as receiving money, drugs, or a place stay in exchange for sex. We assessed lifetime history of sex with male partners as well as sex with men in the six months before incarceration given low levels of reported sex with men. We assessed involvement with high-risk sex partners, indicated by sex in the six months before incarceration with partners who were non-monogamous (which was defined as having sex with other people at the same time they were in a sexual relationship with the participant) and with partners who had ever had an STI (defined to the participant as a “disease that you can get from having sex”).

Sexually Transmitted Infection

We assessed whether participants had any previous diagnosis of an STI by self-report by asking if they had ever had a disease that you can get from having sex. We examined prevalent STI using urine NAAT testing for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Aptima Combo 2, Hologic|Gen-Probe, Inc.) and Trichomonas vaginalis (Aptima T. vaginalis analyte-specific reagents, Hologic|Gen-Probe, Inc.) in a CLIA-certified lab. In the case of an initial positive STI test result, confirmatory testing with the same assay was performed.

Poverty, Mood Disorders, and Substance Use and Treatment

Poverty Indicators

The interview assessed three functional poverty indicators in the six months before incarceration including joblessness, defined as having neither full nor part-time employment; homelessness defined as experiencing a time when the participant considered himself to be homeless; and food insecurity defined as concern about having enough food for himself/his family.

Mood Disorders

Depressive symptoms were measured using a modified version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) (60). This abbreviated 5-item version asked participants how they generally felt or behaved when in the community in the six months before incarceration (i.e., “You felt life was not worth living” or “You were happy”). Response categories ranged from “Never/rarely” (0) to “Most of the time/all the time” (3). The positive item (“You were happy”) was reverse coded and responses to the five items were summed with potential scores ranging from 0 to 15. The five-item scale has demonstrated factor invariance across racial/ethnic groups and hence is appropriate for administration in African American populations (61). When calibrating the 5-item scale to the complete 20-item scale, a total score of 4 or higher on the 5-item scale suggested symptoms indicative of major depression in adults (62). In a sub-group of participants, trait anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to assess how the participant generally felt (63). Specifically, participants were asked to think back to how they “generally feel when you are living outside of prison, in the community” and to indicate how often they felt each of 20 emotions (e.g., calm, relaxed, nervous). Response categories ranged from “Almost Never” (1) to “Almost always” (4). The positive items (e.g., “I felt calm”) were reverse coded and responses to the 20 items were summed with potential scores ranging from 20 to 80. Scores from the scale were summed, with a score of ≥40 corresponding to symptoms indicative of clinical anxiety (63).

Substance Use and Treatment

We assessed binge drinking on a typical day in the six months before incarceration by asking “in six months before this incarceration, how many standard drinks containing alcohol did you have on a typical day?” Those who drank five or more drinks on a typical day were considered typical binge drinkers. Given the relatively low levels of reported drug use in the six months before incarceration, we assessed lifetime drug use. Specifically, we assessed whether participants had ever used powder cocaine, crack, hallucinogens, ecstasy, and/or injection drugs. Marijuana is the most commonly used illegal drug, hence we evaluated frequent use (lifetime history of using multiple times per week or 100 times or more) versus rare use (never or once in the lifetime) and occasional use (more often than once but never used frequently). We assessed receipt of any prior alcohol use treatment among past six month binge drinkers.

Data Analyses

We performed analyses in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Among men who were screened and deemed eligible for participation, we compared socio-demographic and criminal justice involvement factors of study participants versus those who elected not to participate. We used univariable analyses to describe poverty status, mood disorder symptoms, substance use levels and treatment, and STI/HIV risk (sexual risk behavior and STI). We used logistic regression to estimate unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for associations between poverty indicators (joblessness, homelessness, food insecurity in the six months before incarceration), each mood disorder (depression in the six months before incarceration; trait anxiety), and each substance use indicator (binge drinking on a typical day in the past six months and lifetime use of marijuana, crack, cocaine, and ecstasy) and three STI/HIV risk outcomes (concurrent partnerships, buying sex, prevalent STI). When measuring adjusted associations between poverty and STI/HIV risk outcomes, we adjusted for age (continuous), depression (dichotomous), binge drinking on a typical day in the six months before incarceration (dichotomous), any hard drug use (dichotomous; lifetime use of crack, cocaine, ecstasy, hallucinogens, or injection drugs), and number of years incarcerated in prison (three-level nominal categorical variable; <1 year, 1–5 years, >5 years). When measuring adjusted associations between mood disorder indicators and STI/HIV risk, covariates included age, poverty as indicated by food insecurity, binge drinking, hard drug use, and years incarcerated. When measuring adjusted associations between substance use indicators and STI/HIV risk, covariates included age, poverty as indicated by food insecurity, symptoms of depression, and years incarcerated. We did not include anxiety as a covariate in models given null associations between anxiety and STI/HIV risk outcomes, suggesting this variable is likely not a confounder. We addressed confounding by poverty by controlling for food insecurity given the strong associations between food insecurity and some STI/HIV risk outcomes, suggesting this poverty indicator may be a strong confounder.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

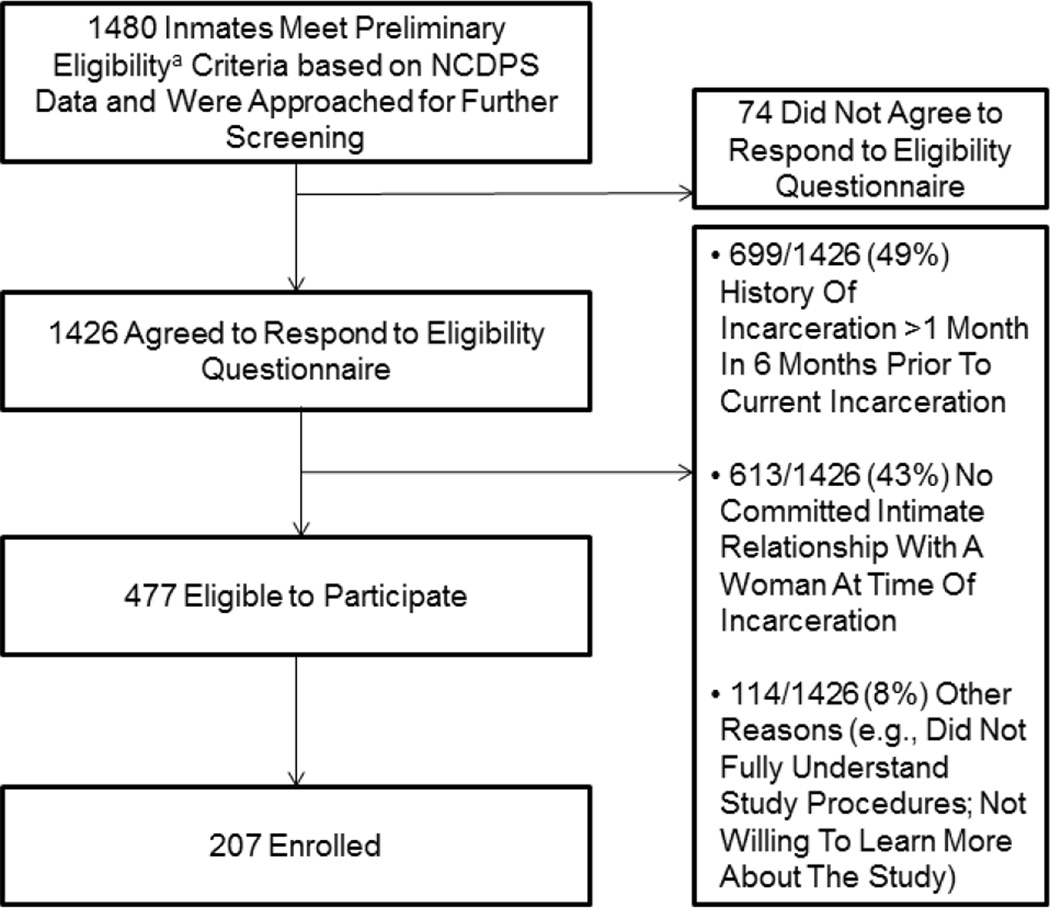

A total of 1,480 male inmates met preliminary eligibility criteria based on pre-screening and were invited for further screening. Of these, 1,426 (96% of 1, 480) agreed to be screened further of whom 477 were eligible (Figure 1). Among ineligible men, the most common reasons for ineligibility included a history of incarceration for >1 month in the 6 months prior to the current incarceration (49%) and not having a committed partnership with a woman at the time of incarceration (43%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of pre-screening and eligibility assessment for Project DISRUPT. aAfrican American; male; at least 18 years old; scheduled to be released from an eligible NCDPS prison within 2 months of recruitment; incarcerated for <36 months; HIV-negative based on HIV testing at prison intake; not incarcerated currently for forcible rape, murder 1, murder 2, or kidnapping; and not held in segregation at the time of recruitment

Mid-way through the study, we expanded recruitment to inmates returning to locations outside of central North Carolina. Participants returning to within versus outside of central North Carolina did not differ significantly (at the 0.05 level) on background factors such as age, employment, concern about bills, food insecurity, depression, and common substance use variables including binge drinking, crack, and cocaine use. We examined differences in STI risk behavior and infection outcomes by home community and observed levels of concurrent partnerships tended to be higher among those returning to outside versus inside central North Carolina (X2=4.78, p=0.03) while levels of sex trade and STI did not differ significantly by residence.

Of the 477 who were deemed fully eligible, 207 (43%) agreed to participate. Cohort members did not appear to differ from non-participators on socio-demographic and criminal justice involvement factors (Table I). The median age for participants was 31 years and 32 years for those who declined participation; the median sentence length was 221 days for participants and 198 days for those who declined (Table I). There were no differences by participation status in education or whether incarcerated for a violent crime.

Table I.

Comparison of Participants and Non-participants, among those Screened and found to be Eligible for Project DISRUPT Participation (N=477)

| Participants (n=207) |

Non-participants (n=270) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Median | T-test (p value) | |

| Age | 31.0 years | 32.0 years | 0.17 (0.86) |

| Sentence length (days) | 221 days | 198 days | −1.11 (0.26) |

| Percent | Percent | X2 (p value) | |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 33.3 | 35.2 | 2.11 (0.35) |

| High school or equivalent | 42.7 | 46.2 | |

| >High school | 24.0 | 18.6 | |

| In school or training program before incarceration | |||

| No | 81.5 | 87.1 | 2.56 (0.28) |

| Yes, high school level | 12.2 | 8.3 | |

| Yes, >high school level | 6.4 | 5.6 | |

| Currently incarcerated for violent crime | 26.6 | 24.1 | 0.39 (0.53) |

Criminal Justice History

Approximately 53% of participants had been incarcerated in prison for less than one year total in their lifetime, 28% had been incarcerated between one to five years, and 19% had been incarcerated for more than five years (Table II).

Table II.

Baseline Socio-economic Characteristics, Mental Health, Substance Use and STI/HIV Risk Indicators among Incarcerated African American Men in Committed Partnerships (Project DISRUPT; N=189)

| Characteristic | Total Numbera (Percent) |

|---|---|

| Criminal Justice History | |

| Total Number of Years Incarcerated in Prison | |

| <1 Year | 99 (52.9) |

| 1–5 Years | 53 (28.3) |

| >5 Years | 35 (18.7) |

| Poverty Indicators | |

| Joblessness (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| No | 112 (59.3) |

| Yes | 70 (37.0) |

| Homelessness (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| No | 149 (78.8) |

| Yes | 34 (18.0) |

| Food Insecurity (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| No | 138 (73.0) |

| Yes | 43 (22.8) |

| Mood Disorders | |

| Depressed (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| No | 115 (60.9) |

| Yes | 74 (39.2) |

| Trait Anxietyb | |

| No | 77 (56.6) |

| Yes | 59 (43.4) |

| Substance Use and Treatment | |

| Binge Drinking on a Typical Day (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| No | 128 (67.7) |

| Yes | 38 (20.1) |

| Lifetime Marijuana Use | |

| Rare Use | 14 (7.4) |

| Occasional Use | 44 (23.3) |

| Frequent Use | 126 (66.7) |

| Lifetime Crack Use | |

| No | 142 (75.1) |

| Yes | 43 (22.8) |

| Lifetime Cocaine Use | |

| No | 134 (70.9) |

| Yes | 51 (27.0) |

| Lifetime Ecstasy Use | |

| No | 133 (70.4) |

| Yes | 51 (27.0) |

| Lifetime Hallucinogen Use | |

| No | 171 (90.5) |

| Yes | 13 (6.9) |

| Lifetime Injection Drug Use | |

| No | 176 (93.1) |

| Yes | 9 (4.8) |

| Any Prior Alcohol Treatment, among Past 6 Month Binge Drinkers | |

| No | 14 (44.7) |

| Yes | 21 (55.3) |

| Sexual Risk-Taking and Sexually Transmitted Infection (6 Months Before Incarceration) | |

| Multiple Partnerships | |

| No | 98 (51.9) |

| Yes | 79 (41.8) |

| Concurrent Partnerships | |

| No | 120 (63.5) |

| Yes | 62 (32.8) |

| Sex without a Condom with a New/Casual Female Partner | |

| No | 90 (47.6) |

| Yes | 87 (46.0) |

| Sex with Male Partnersc | |

| No | 188 (99.5) |

| Yes | 1 (0.5) |

| Bought Sex from Female Partners | |

| No | 164 (86.8) |

| Yes | 19 (10.1) |

| Sold Sex to Female Partners | |

| No | 182 (96.3) |

| Yes | 4 (2.1) |

| Bought Sex from Male Partners | |

| No | 189 (100.0) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) |

| Sold Sex to Male Partners | |

| No | 189 (100.0) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex with Non-Monogamous Partners | |

| No | 127 (67.2) |

| Yes | 52 (27.5) |

| Sex with Partners who Ever Had STI | |

| No | 155 (82.0) |

| Yes | 25 (13.2) |

| Ever Diagnosed with an STI | |

| No | 119 (63.0) |

| Yes | 65 (34.4) |

| Prevalent STI | |

| No | 169 (90.4) |

| Yes | 17 (9.0) |

May not sum to 189 (100%) due to missing values.

In subsample of 136 participants.

Seven participants (3.7%) reported a lifetime history of sex with a male partner.

Poverty

In the six months before incarceration, 37% were jobless and approximately one in five reported being homeless (18%) and/or having food insecurity (23%) (Table II).

Mood Disorders

Mood disorder symptoms were common; 39% endorsed symptoms indicative of major depression in the six months before incarceration based on the CES-D and 43% endorsed symptoms indicative of an anxiety disorder based on the Trait Inventory of the STAI (Table II).

Substance Use and Treatment

Among cohort participants, 20% reported binge drinking on a typical day in the six months prior to incarceration (Table II). The most commonly used drug was marijuana, with 67% reporting a lifetime history of frequent use and an additional 23% reporting a lifetime history of occasional use. Participants aged 40 years or older were much less likely to report frequent marijuana use than those aged less than 40 years (prevalence 40+ years: 57%, <40 years: 71%; OR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.09–0.86). Approximately one-fourth reported ever having used crack (23%), powder cocaine (27%), and ecstasy (27%). Use of these drugs differed significantly by age. Participants 40 years or older were much more likely than their younger counterparts to have used crack (prevalence 40+ years: 60%, <40 years: 5%; OR: 25.30, 95% CI: 10.10–63.50) and cocaine (prevalence 40+ years: 38%, <40 years: 22%; OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.10–4.21) and less likely to have used ecstasy (prevalence 40+ years: 8%, <40 years: 36%; OR: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.06–0.41). Small percentages reported prior use of hallucinogens (7%) and injection drugs (5%). Approximately 45% of those with a history of binge drinking in the period just prior to incarceration had never received treatment to address alcohol use.

Sexual Risk Behavior and Prevalent STI

In the six months before incarceration, substantial proportions had multiple (42%) and concurrent (33%) partnerships (Table II). Approximately half of participants reported a history of sex without a condom during sex with a casual or new female partner in the six months before incarceration. Less than four percent of participants reported sex with male partners in their lifetime and one participant (0.5%) endorsed sex with male partners in the six months before incarceration. Ten percent reported buying sex from female partners and two percent reported selling sex to female partners in the six months before incarceration. No participants endorsed sex trade involvement, whether buying or selling sex, with male partners. Over one-quarter reported sex with non-monogamous partners (28%) and 13% reported sex with partners who had a history of STI. Few differences in sexual risk-taking were observed by age, with the exception of involvement in buying sex. Participants aged 40 years or older were much more likely than those aged less than 40 years to report buying sex (OR: 2.92, 95% CI: 1.14–7.49).

Over 30% reported a prior history of diagnosis with an STI, and 9% tested positive for an STI (chlamydia: 4.2%, gonorrhea: 0.5%, trichomoniasis: 4.2%).

Poverty, Mood Disorder, and Substance Use Correlates of Sexual Risk Behaviors

Poverty

Self-reported joblessness was a risk factor for concurrent partnerships in the six months before incarceration in both unadjusted analyses and multivariable models (adjusted OR: 2.88, 95% CI: 1.40–5.94) (Table III). Joblessness was not linked to buying sex. Those who reported being homeless in the six months before incarceration had three times the odds of buying sex in the six months before incarceration versus those who did not report being homeless (OR: 3.35, 95% CI: 1.19–9.45). In adjusted models, the association weakened and was no longer statistically significant (adjusted OR: 2.73, 95% CI: 0.83–8.98). Homelessness was not a correlate of concurrency. Food insecurity was strongly associated with buying sex in the six months before incarceration in both unadjusted and adjusted models (adjusted OR: 5.97, 95% CI: 1.83–19.45). Food insecurity was not associated with concurrency.

Table III.

Poverty, Mood Disorder, and Substance Use Correlates of STI/HIV Risk among Incarcerated African American Men in Committed Partnerships (N=189)

| Concurrent Partnerships | Buying Sex | Prevalent STI | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | % | OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Poverty Indicators | ||||||||||||||||||

| Joblessness | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 28.6 | 1 | 1 | 10.7 | 1 | 1 | 10.7 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 42.9 | 1.97 (1.05, 3.71) | 2.88 (1.40, 5.94) | 10 | 0.93 (0.35, 2.49) | 1.20 (0.40, 3.58) | 5.7 | 0.52 (0.16, 1.67) | 1.39 (0.44, 4.44) | |||||||||

| Homelessness | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 31.5 | 1 | 1 | 7.4 | 1 | 1 | 9.4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 41.2 | 1.57 (0.72, 3.39) | 1.81 (0.77, 4.28) | 20.6 | 3.35 (1.19, 9.45) | 2.73 (0.83, 8.98) | 5.9 | 0.61 (0.13, 2.84) | 0.77 (0.15, 3.98) | |||||||||

| Food Insecurity | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 34.1 | 1 | 1 | 5.8 | 1 | 1 | 10.1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 32.6 | 0.96 (0.46, 1.99) | 0.92 (0.39, 2.18) | 25.6 | 5.54 (2.06, 14.91) | 5.97 (1.83, 19.45) | 4.7 | 0.44 (0.10, 2.00) | 0.49 (0.09, 2.60) | |||||||||

| Mood Disorders | ||||||||||||||||||

| Depressed | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 28.2 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 | 1 | 1 | 8.9 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 43.1 | 1.93 (1.03, 3.60) | 1.96 (0.96, 4.02) | 17.8 | 3.76 (1.36, 10.40) | 2.98 (0.85, 10.36) | 9.6 | 1.09 (0.40, 3.01) | 1.51 (0.45, 5.11) | |||||||||

| Trait Anxietyb | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 36.4 | 1 | 1 | 7.8 | 1 | 1 | 7.9 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 31 | 0.79 (0.38, 1.63) | 0.57 (0.23, 1.42) | 11.9 | 1.59 (0.51, 5.02) | 1.07 (0.21, 5.52) | 8.6 | 1.10 (0.32, 3.80) | 0.92 (0.19, 4.48) | |||||||||

| Substance Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| Binge Drinking on Typical Drinking Day (6 Months before Incarceration) | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | ||||||||||||||||||

| 33.1 | 1 | 1 | 10.5 | 1 | 1 | 5.2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 46 | 1.72 (0.82, 3.61) | 1.75 (0.79, 3.90) | 13.2 | 1.29 (0.43, 3.84) | 1.46 (0.42, 5.06) | 19.4 | 4.38 (1.43,13.46) | 3.79 (1.19, 12.04) | ||||||||||

| Lifetime Marijuana Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rare Use | 23.1 | 1 | 1 | 15.4 | 1 | 1 | 0.0c | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| Occasional Use | 25 | 1.11 (0.26, 4.78) | 0.81 (0.18, 3.68) | 6.8 | 0.40 (0.06, 2.72) | 0.27 (0.03, 2.34) | 11.6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Frequent Use | 39 | 2.13 (0.86, 8.15) | 1.25 (0.30, 5.23) | 11.3 | 0.70 (0.14, 3.49) | 0.50 (0.08, 3.34) | 8.9 | 0.74 (0.24, 2.27) | 0.69 (0.22, 2.24) | |||||||||

| Lifetime Crack Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 35.2 | 1 | 1 | 7.1 | 1 | 1 | 7.9 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 31 | 0.82 (0.39, 1.73) | 2.04 (0.71, 5.84) | 21.4 | 3.55 (1.33, 9.43) | 1.27 (0.30, 5.34) | 11.9 | 1.58 (0.52, 4.85) | 1.98 (0.71, 9.52) | |||||||||

| Lifetime Cocaine Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 32.8 | 1 | 1 | 7.6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 38 | 1.25 (0.64, 2.47) | 1.46 (0.70, 3.03) | 18 | 2.68 (1.02, 7.05) | 2.37 (0.80, 7.04) | 16.3 | 3.05 (1.08, 8.64) | 2.53 (0.84, 7.62) | |||||||||

| Lifetime Ecstasy Use | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 29.2 | 1 | 1 | 9.9 | 1 | 1 | 9.9 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Yes | 48 | 2.23 (1.14, 4.37) | 1.68 (0.83, 3.42) | 12 | 1.24 (0.44, 3.46) | 2.05 (0.57, 5.38) | 6 | 0.58 (0.16, 2.13) | 0.58 (0.15, 2.22) | |||||||||

Adjusted models poverty are adjusted for age, depression, binge drinking, any hard drug use (lifetime use of crack, cocaine, ecstasy, hallucinogens, or injection drug use) and number of years incarcerated in lifetime; adjusted models for mood disorders are adjusted for age, food insecurity, binge drinking, any hard drug use, and number of years incarcerated in lifetime; adjusted models for substance use are adjusted for age, food insecurity, depression, and number of years incarcerated in lifetime.

In subsample of 136 participants

Tabular analyses suggest the percentage testing positive for STI do not differ significantly by marijuana use (X2 =1.7725; p=0.4122).

Mood Disorders

Those who endorsed symptoms of major depression based on the modified version of the CES-D had twice the odds of concurrent partners in the six months before incarceration as those who did not have depressive symptoms (OR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.03–3.60). In models adjusting for age, food insecurity, binge drinking, any hard drug use, and number of years incarcerated, the association appeared to remain though the precision decreased and the result was no longer significant at the 0.05 level (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 0.96–4.02). Depression was strongly tied to buying sex (OR: 3.76, 95% CI: 1.36–10.40). In adjusted models the OR was 2.98 and the result was no longer statistically significant (CI: 0.85–10.36).

Substance Use

Binge drinking and marijuana use were not associated with concurrent partnerships or buying sex in the six months before incarceration. Use of crack and cocaine were each statistically significantly associated with over twice the odds of buying sex in unadjusted models (crack OR: 3.55, 95% CI: 1.33–9.43; cocaine OR: 2.68, 95% CI: 1.02–7.05). In models adjusting for age, food insecurity, depression, and number of years incarcerated, associations weakened and were no longer statistically significant (adjusted crack OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 0.30–5.34); adjusted cocaine OR: 2.37, 95% CI: 0.80–7.04). The variables that caused the greatest confounding effects were age and food insecurity for crack and depression and number of years incarcerated for cocaine. Crack/cocaine use was not associated with concurrency. Ecstasy use was associated with concurrency (OR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.14–4.37), but the association no longer remained in multivariable models. Ecstasy use was not associated with buying sex.

Poverty, Mood Disorder, and Substance Use Correlates of Prevalent STI

Poverty and mood disorder indicators were not correlates of STI.

Binge drinking in the six months before incarceration was associated with STI in unadjusted and adjusted models (adjusted OR: 3.79, 95% CI: 1.19–12.04). Of those who reported no prior marijuana use or ever having used marijuana once, none were infected with an STI. Levels of STI were higher among participants reporting occasional (12%) and frequent (9%) lifetime marijuana use though tabular analyses suggested no difference in STI among rare, occasional, or frequent users (X2 =1.77; p=0.41). Calculation of odds ratios to compare occasional or frequent users to rare users was not possible given the zero cell count in rare users of marijuana. Regression analyses suggested no difference in STI comparing occasional and frequent users. Lifetime cocaine use was strongly associated with STI (OR: 3.05, 95% CI: 1.08–8.64). In adjusted models, the association weakened somewhat, the precision was reduced, and the result was no longer statistically significant (adjusted OR: 2.53, 95% CI: 0.84–7.62). Crack and ecstasy use did not appear to be associated with STI in the sample.

DISCUSSION

Sexual risk behavior prior to incarceration was common in this cohort of African American men in committed partnerships with women. More than one-third reported multiple and concurrent relationships. Further, approximately 10% had an STI detected prior to release. Poverty and depression were common and strongly associated with risky behavior, and substance abuse, particularly binge drinking, was strongly associated with prevalent STI. These results indicate clearly the need for improved STI testing, treatment, and prevention education as well as mental health and substance use diagnosis in correctional facilities. Results of adjusted analyses suggest treatment of heavy alcohol use may be critical to STI control efforts; that treating depression may help reduce risk-taking though additional investigation is warranted; and that efforts to mitigate poverty during incarceration and release (e.g., by offering education and job training/placement) may improve well-being and reduce sex risk.

One particularly troubling finding that emerged from this baseline study was that nearly one in ten African American men in North Carolina prisons in committed partnerships with women tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis. It is improbable that these infections were acquired during the incarceration and much more likely that these men entered prison infected. Correctional facilities do not routinely test for these infections though they are easily treatable at relatively low cost. Upon release, untreated infection may place prior partners to whom releasees return and/or new partners at risk for STI. Further, STI can increase susceptibility to HIV infection (58, 59), placing these men at greater risk of acquiring HIV if exposed after release. These results support prior studies documenting high levels of STI among inmates and underscore the call to action for expanded STI testing and treatment in correctional facilities (10). There is a staggering race disparity in STI as well as HIV in the US (64). Failure to implement correctional facility-based STI testing, treatment, and education remains a tragic missed opportunity to address the race disparity in infection given that hundreds of thousands of African Americans cycle through jails and prisons annually.

Approximately 40% of the sample reported symptoms suggestive of depressive and anxiety disorders that had existed prior to incarceration; these mood disorder symptom levels are significantly higher than observed in general-population African Americans (65, 66). In addition, daily binge drinking prior to incarceration and a history of hard drug use were common. Nearly half of those who reported daily binge drinking had never received prior alcohol treatment. Based on our findings of association prior to statistical adjustment, African American men involved in the criminal justice system who are diagnosed with depressive symptoms, who used drugs, and/or who binged constitute priority populations for STI/HIV testing, treatment, and prevention education. Likewise, those reporting STI/HIV risk behaviors would constitute a population not only in need of STI/HIV prevention education, but also screening for mood disorders and addictions. Addressing the co-morbidities of mood disorders and addictions has long been known to constitute an important priority for correctional health programming that has implications for reduced rates of reentry (67), and addressing these factors is considered to be important for reduced STI/HIV risk (44, 55). There remains a need to strengthen substance use treatment in corrections (55) while mental health services and discharge planning within correctional facilities currently are inconsistent and inadequate (68, 69). When addressing substance use in the context of STI/HIV prevention among inmates, programming should be tailored for older versus younger inmates given the dramatic cohort differences in drug use observed.

Among DISRUPT cohort members, substantial proportions reported socio-economic deprivation. Specifically, approximately 40% of the Project DISRUPT cohort reported joblessness in the six months before the incarceration, and nearly one in five had a recent history of homelessness. Observed high levels of socio-economic deprivation are consistent with extant research documenting disproportionate poverty levels among inmates (70). The most socio-economically vulnerable inmates experienced the highest levels of sexual risk behavior. Prior studies have suggested socio-economic deprivation plays a role in the development of depression, in substance use, and in the HIV epidemic among African Americans (71–75). Incarceration exacerbates the effects of economic hardship by reducing inmates’ employment prospects, thus increasing their risk of poverty after release from prison (76). Further impoverishment might also exacerbate adverse mental health outcomes and STI/HIV risk after release. Programs delivered during incarceration and at re-entry that improve education and employment prospects are associated with reduced drug use, STI/HIV risk, and incarceration (77, 78). These promising intervention studies highlight the value of evaluating poverty-reduction interventions as a means of improving well-being and reducing STI/HIV risk.

An important limitation of Project DISRUPT is that many men in committed partnerships were excluded due to our eligibility criteria, designed to allow examination of the effects of partnership dissolution on post-release behaviors. However, these criteria limited both the sample size of the cohort, which negatively impacts statistical power to detect modest associations and low-prevalence outcomes, as well as the generalizability of the findings. The second most important limitation is the cross-sectional data structure of these analyses, which limits our ability to interpret associations as causal. An important limitation that stems from the cross-sectional data structure is recall bias, as participants are asked to think back to remember events, behaviors, or emotions during the six months before the start of the incarceration. For example, though we ask participants to recall depressive symptoms felt in the six months before incarceration, it is possible that the process of incarceration could have influenced depression and participants’ responses to the CES-D reflect current rather than prior depressive symptoms rather than symptoms in the six months before incarceration. Finally, social desirability biases are likely given the sensitive nature of these topics. For example, the relatively low prevalence of lifetime use of crack/cocaine – lower than observed in our other prior studies in similar populations in the NCDPS – suggests that underreporting of risk behavior is likely a concern despite the attempt to use ACASI methods to improve confidentiality of reporting.

CONCLUSIONS

The period of incarceration has long been seen as a critical time for addressing public health concerns (79). Strengthening correctional programs that address mental illness, substance use, and STI/HIV risk are critical for protecting the health of men involved in the criminal justice system and may have positive effects of the health of their relationships and in turn their partners. These programs should be coupled with efforts to address the poverty that contributes to incarceration and that characterizes the environments from which inmates come and to which they return. In addition, poverty-alleviation programming should be further evaluated as a component of STI/HIV prevention for those involved in the criminal justice system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIDA R01DA028766 (PI: Khan) and the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research [AI050410]. Dr. Golin’s salary was partially supported by K24 HD06920. Dr. Friedman was supported by Theory Core of CDUHR P30 DA11041. Dr. Adimora was supported by 1K24HD059358. Laboratory testing for STIs was supported in part by the Southeastern Sexually Transmitted Infections Cooperative Research Center grant U19-AI031496 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. [cited 2014 July];2014 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/aa/facts/index.html.

- 2.United States Census Bureau. USA: State and county quickfacts. [cited 2015 March];2015 Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. African Americans and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. [cited 2014 April];2012 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/AAs-and-STD-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

- 4.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prisoners in 2013. U.S. Department of Justice. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauer M, King RS. A 25-Year Quagmire: The War on Drugs and Its Impact on American Society. 2007 The Sentecing Project, September Report. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adimora AA, Schoenbach V. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191:S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MR, Epperson M, Comfort M. A novel conceptual model that describes the influence of arrest and incarceration on STI/HIV transmission. 140th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; San Francisco, CA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: Sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among Inmates of and Releasees from US Correctional Facilities, 2006: Declining Share of Epidemic but Persistent Public Health Opportunity. PloS one. 2009;4(11):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kouyoumdjian FG, Leto D, John S, Henein H, Bondy S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis in incarcerated persons. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(4):248–254. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, Weir SS, Kaufman JS, Wohl DA, et al. Timing and Duration of Incarceration and High-Risk Sexual Partnerships Among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, Adimora AA, Moseley C, Norcott K, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2008;85(1):100–113. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers SM, Khan MR, Tan S, Turner CF, Miller WC, Erbelding E. Incarceration, high-risk sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted infections in an urban population. Sexually transmitted infections. 2012;88(1):63–68. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2010;87(2):324–336. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whetten K, Reif S. Overview: HIV/AIDS in the deep south region of the United States. AIDS care. 2006;18(Suppl 1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reif S, Geonnotti KL, Whetten K. HIV Infection and AIDS in the Deep South. American journal of public health. 2006;96(6):970–973. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tracking the hidden epidemics: Trends in STDS in the United States. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-release STI/HIV risk behavior in a Southeastern city. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e969d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, White BL, Wohl DA. Dissolution of Primary Intimate Relationships during Incarceration and Implications for Post-release HIV Transmission. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2011;88(2):365–375. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolton J, Cox B, Clara I, Sareen J. Use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(11):818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000244481.63148.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandell W, Kim J, Latkin C, Suh T. Depressive symptoms, drug network, and their synergistic effect on needle-sharing behavior among street injection drug users. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 1999;25(1):117–127. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins WE, Latkin C, Hawkins MJ, Chowdury D. Depressive symptoms and HIV-risk behavior in inner-city users of drug injections. Psychol Rep. 1998;82(1):137–138. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addictive behaviors. 1998;23(6):717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW, Jr, Bigelow GE. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo Mezzich A, Tarter RE, Giancola PR, Lu S, Kirisci L, Parks S. Substance use and risky sexual behavior in female adolescents. Drug and alcohol dependence. 1997;44(2–3):157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinwiddie SH. Characteristics of injection drug users derived from a large family study of alcoholism. Comprehensive psychiatry. 1997;38(4):218–229. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, Bulto M. Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(2):221–227. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasin DS, Glick H. Depressive symptoms and DSM-III-R alcohol dependence: general population results. Addiction. 1993;88(10):1431–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Latkin CA, Mandell W. Depression as an antecedent of frequency of intravenous drug use in an urban, nontreatment sample. Int J Addict. 1993;28(14):1601–1612. doi: 10.3109/10826089309062202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Simpson EE. Adult marijuana users seeking treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1993;61(6):1100–1104. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rounsaville BJ, Anton SF, Carroll K, Budde D, Prusoff BA, Gawin F. Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(1):43–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Jama. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross HE, Glaser FB, Germanson T. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alcohol and other drug problems. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(11):1023–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Crits-Christoph K, Wilber C, Kleber H. Diagnosis and symptoms of depression in opiate addicts. Course and relationship to treatment outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(2):151–156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290020021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance Use and Risky Sexual-Behavior for Exposure to Hiv - Issues in Methodology, Interpretation, and Prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. International journal of public health. 2010;55(3):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(3):156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latkin CA, Williams CT, Wang J, Curry AD. Neighborhood social disorder as a determinant of drug injection behaviors: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2005;24(1):96–100. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margolis AD, MacGowan RJ, Grinstead O, Sosman J, Kashif I, Flanigan TP. Unprotected sex with multiple partners: implications for HIV prevention among young men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):175–180. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187232.49111.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sosman J, Macgowan R, Margolis A, Gaydos CA, Eldridge G, Moss S, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis in men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(7):634–639. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820bc86c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiat Serv. 2005;56(7):840–846. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: A systematic review. Clinical psychology review. 2005;25(4):433–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan MR, Kaufman JS, Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adimora AA, Weir SS, et al. Depression, sexually transmitted infection, and sexual risk behavior among young adults in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(7):644–652. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramrakha S, Caspi A, Dickson N, Moffitt TF, Paul C. Psychiatric disorders and risky sexual behaviour in young adulthood: cross sectional study in birth cohort. Brit Med J. 2000;321(7256):263–266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reyes JC, Robles RR, Colon HM, Marrero CA, Matos TD, Calderon JM, et al. Severe anxiety symptomatology and HIV risk behavior among Hispanic injection drug users in Puerto Rico. AIDS and behavior. 2007;11(1):145–150. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs and escape: a psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS care. 1996;8(6):655–669. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lejoyeux M, Arbaretaz M, McLoughlin M, Ades J. Impulse control disorders and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(5):310–314. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanson KL, Luciana M, Sullwold K. Reward-related decision-making deficits and elevated impulsivity among MDMA and other drug users. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao U. Links between depression and substance abuse in adolescents: neurobiological mechanisms. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6 Suppl 1):S161–S174. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aseltine RJ, Gore S, Colten M. Depression and the social development context of adolescence. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1994;67:252–263. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belenko S, Peugh J. Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77(3):269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, Morrow K, Zack B, Askew J, et al. Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(8):519–523. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to Diagnose, Treat, and Prevent HIV in the Criminal Justice System. Jaids-J Acq Imm Def. 2010;55:S49–S55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):187–193. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westrom L, Eschenbach D. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mårdh P, editors. Sex Transm Dis. Third ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 783–809. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen MS. HIV and sexually transmitted diseases: lethal synergy. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2004;12(4):104–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually transmitted infections. 1999;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, Bollen K. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ethnicity and immigrant generation. Soc Forces. 2005;83(4):1567–1601. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, Chatters LM. Correlates of Psychological Distress and Major Depressive Disorder Among African American Men. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21(3):278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prevention CfDCa. HIV Among African Americans. 2014 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/aa/facts/index.html.

- 65.Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, Blanco C. Mental Health of African Americans and Caribbean Blacks in the United States: Results From the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American journal of public health. 2013;103(2):330–338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor RJ, Chae DH, Chatters LM, Lincoln KD, Brown E. DSM-IV Twelve Month and Lifetime Major Depressive Disorder and Romantic Relationships among African Americans. Journal of Affect Disorder. 2012;142(1–3):339–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Draine JWN. Social capital and reentry to the community from prison. Rutgers University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pope LG, Smith TE, Wisdom JP, Easter A, Pollock M. Transitioning Between Systems of Care: Missed Opportunities for Engaging Adults with Serious Mental Illness and Criminal Justice Involvement. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2013;31:444–456. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rich JD, Wohl DA, Beckwith CG, Spaulding AC, Lepp NE, Baillargeon J, Gardner A, Avery A, Altice FL, Springer S. HIV-Related Research in Correctional Populations: Now is the Time. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):288–296. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Western B, Muller C. Mass Incarceration, Macrosociology, and the Poor. Ann Am Acad Polit Ss. 2013;647(1):166–189. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA. Ending the Epidemic of Heterosexual HIV Transmission Among African Americans. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2009;37(5):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krueger L, Wood RW, Diehr PH, Maxwell CL. Poverty and HIV seropositivity: the poor are more likely to be infected. Aids. 1990;4(8):811–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Osypuk TL, Rapp SR, Seeman T, Watson KE. Is neighborhood racial/ethnic composition associated with depressive symptoms? The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Social science & medicine. 2010;71:541e50. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hudson DL, Neighbors HW, Geronimus AT, J.S Jackson JS. The relationship between socioeconomic position and depression among a US nationally representative sample of African Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:373–381. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buka SL. Disparities in Health Status and Substance Use: Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Factors. Public Health Reports. 2002;117 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public Health and the Epidemic of Incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fabelo T. The impact of prison education on community reintegration of inmates: The Texas case. Journal of Correctional Education. 2002;52(3):106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freudenberg N, Ramaswamy M, Daniels J, Crum M, Ompad DC, Vlahov D. Reducing Drug Use, Human Immunodeficiency Virus Risk, and Recidivism Among Young Men Leaving Jail: Evaluation of the REAL MEN Re-entry Program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(5):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rich JD, DiClemente R, Levy J, Lyda K, Ruiz MS, Rosen DL, Dumont D. Correctional Facilities as Partners in Reducing HIV Disparities. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2013;63:S49–S53. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318292fe4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]