Abstract

Purpose

BNC105P inhibits tubulin polymerization, and preclinical studies suggest possible synergy with everolimus. In this phase I/II study, efficacy and safety of the combination were explored in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC).

Experimental Design

A phase I study in patients with clear cell mRCC and any prior number of therapies was conducted using a classical 3+3 design to evaluate standard doses of everolimus with increasing doses of BNC105P. At the recommended phase II dose (RP2D), patients with clear cell mRCC and 1-2 prior therapies (including ≥1 VEGF-TKI) were randomized to BNC105P with everolimus (Arm A) or everolimus alone (Arm B). The primary endpoint of the study was 6-month progression-free survival (6MPFS). Secondary endpoints included response rate, PFS, overall survival (OS) and exploratory biomarker analyses.

Results

In the phase I study (n=15), a dose of BNC105P at 16 mg/m2 with everolimus at 10 mg daily was identified as the RP2D. In the phase II study, 139 patients were randomized, with 69 and 67 evaluable patients in Arms A and B, respectively. 6MPFS was similar in the treatment arms (Arm A: 33.82% v Arm B: 30.30%, P=0.66) and no difference in median PFS was observed (Arm A: 4.7 mos v Arm B: 4.1 mos; P=0.49). Changes in matrix metalloproteinase-9, stem cell factor, sex hormone binding globulin and serum amyloid A protein were associated with clinical outcome with BNC105P.

Conclusions

Although the primary endpoint was not met in an unselected population, correlative studies suggest several biomarkers that warrant further prospective evaluation.

Keywords: BNC105P, vascular disrupting agent, everolimus, randomized phase II

INTRODUCTION

Current treatment algorithms for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) support use of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-directed therapies in the first-line setting for the majority of patients (e.g., patients with good- and intermediate-risk disease).(1) For patients who progress on these agents, phase III data exist to support several strategies including continued VEGF-directed therapy (e.g., axitinib) or with an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR; e.g., everolimus).(2, 3) Even with various permutations of these agents, mRCC remains an incurable disease. One attempted strategy has been to combine existing VEGF- and mTOR-directed therapies – to date, these efforts have shown concerning toxicity and/or a lack of efficacy.(4, 5) Novel agents that are combinable and synergistic with existing therapies are therefore actively sought.

In the current study, the combination of everolimus with a vascular disrupting agent (VDA) is explored. VDAs are distinct from currently approved VEGF-directed therapies in that they disrupt existing tumor blood vessels rather than suppressing neovasculature.(6) As a result, these agents cause tumor vascular collapse and cessation of blood flow leading to tumor ischemia and necrosis.(7) Preclinical evaluation of combination regimens involving a VDA and an mTOR inhibitor demonstrated synergistic activity leading to improved anti-tumor effects.(8, 9) In these studies, combined therapy was more efficacious in reducing endothelial cell sprouting, causing tumor vascular damage and reducing tumor blood volume.

The novel VDA BNC105P is a disodium phosphate ester prodrug of BNC105, a tubulin polymerization inhibitor that exhibits a high degree of selectivity for tumor endothelial cells.(7) The drug displays >80-fold higher potency against endothelial cells that are actively proliferating or engaged in the formation of capillaries compared with non-proliferating endothelial cells or endothelium found in stable capillaries. A phase I study of BNC105P monotherapy included 21 patients with advanced solid tumors, and identified an intravenous dose of 16 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle for further studies.(10) Although no objective responses were noted, 4 patients (including 1 patient with mRCC) had stable disease (SD) as a best response. Herein, results of a phase I/II study, named DisrupTOR-1, examining the combination of everolimus with BNC105P are reported. To date, VDAs have not been explored in mRCC. The dose-finding phase I component was a lead-in to a randomized phase II design comparing monotherapy with everolimus to the combination of everolimus with BNC105P.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Eligibility

For both the phase I and phase II components of the study, patients were required to have histologically confirmed RCC with a clear cell component. Notably, any proportion of clear cell disease was allowed. Patients were further required to have metastatic disease, a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) of ≥ 70, adequate organ function and measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.0. Key exclusion criteria included collecting duct or medullary histology, active brain metastasis, significant cardiovascular events within 6 months, congestive heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] < 50%), and full dose anticoagulation. Patients may have received any number of prior VEGF-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGF-TKIs) prior to enrollment in the phase I component of the study, but may have received only 1-2 prior VEGF-TKIs prior to enrollment in the phase II component. Prior therapy with an mTOR inhibitor was allowed in the phase I component of the study, but prohibited in the phase II component. Aside from these requirements, there were no limits on the cumulative number of prior therapies rendered. Phase I patients were required to consent to pharmacokinetic (PK) sampling.

Phase I Design and PK Analysis

Everolimus (10 mg) was orally administered daily with a 7 day lead in prior to the first administration of BNC105P. Patients received BNC105P monotherapy on Days 1 and 8 of a 21 day cycle as a 10 min intravenous (IV) injection. BNC105P doses of 4.2, 8.4, 12.6 and 16 mg/m2 were explored. A standard 3+3 dose escalation design was followed, where three patients were treated in each dose level, with expansion to 6 patients if a dose limiting toxicity (DLT) was observed. In the case of a second DLT occurring in a six patient cohort no further escalation was to be undertaken and the cohort of one dose level below was to be expanded to confirm that level as the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Dosing continued until evidence of progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity was observed. The follow-up period was 30 days post administration of last dose.

PK samples for BNC105P and BNC105 analysis in plasma were obtained prior to dosing (baseline), at the end of the injection, at 10, 20, 40, 60 and 90 minutes, and at 2, 4 and 6 hours after completion of the injection on Days 1 and 8 of Cycle 1. PK samples for everolimus analysis in whole blood were obtained prior to BNC105P dosing, at the end of the injection, at 40 and 60 minutes, and at 2, 4 and 6 hours after completion of the BNC105P injection on Days 1 and 8 of Cycle 1. Analytes were separated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, NSW, Australia) and the eluates monitored using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection (Applied Biosystems API4000 mass spectrometer, VIC, Australia). All analytical methods adhered to the GLP principles and the FDA guidance on bioanalytical method validation.

Randomized Phase II Design and Biomarker Analysis

Patients with mRCC meeting the aforementioned eligibility criteria were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to receive either monotherapy with everolimus at standard doses or the recommended phase II doses for the combination of everolimus with BNC105P identified from the lead-in phase I trial. Patients were treated until progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity was observed. Dose reductions were permitted for each agent independently based on investigator attribution of toxicity, and if no attribution could be made, then doses of both drugs were reduced. Patients requiring more than 2 dose reductions were removed from the study. Doses of everolimus were reduced from 10 mg oral daily to 5 mg oral daily to 5 mg oral every other day. Doses of BNC105P were reduced from 16 mg/m2 to 12.6 mg/m2 to 8.4 mg/m2. Notably, at the time of progression, patients receiving everolimus monotherapy were allowed to continue on BNC105P monotherapy until the time of progression. A starting dose of 16 mg/m2 was used, again with the same dose reductions employed.

Blood draws for biomarker assessments in the phase II component of the study were pre-specified and optional. Patients randomized to receive everolimus with BNC105P received blood draws on day 1 and 8 of therapy immediately prior to BNC105P, 1 to 3 hours following BNC105P and at the time of progression. Patients randomized to receive everolimus alone did not receive these blood draws at baseline, but rather received blood draws at identical time points at the time they crossed over onto BNC105P monotherapy. Plasma samples from 44 evaluable patients enrolled in the trial were used to determine plasma concentrations for 40 exploratory biomarkers (Supplementary Table 1). Biomarker concentration determinations were carried out by Myriad RBM using Multi-Analyte Profiling Technology which is based on microsphere immune-multiplexing with Luminex xMAP technology. Briefly, microsphere beads were conjugated to antibodies encoded with unique fluorescent signatures that are specific to each biomarker of interest. Beads and plasma samples were incubated to allow for target binding followed by the addition of detection reagents and fluorescent reporter molecules. Fluorescence generated for each unique biomarker signature in proportion to the biomarker concentration in the sample is acquired using the Luminex xMAP instrumentation with biomarker concentration in samples determined from standard curves for each individual biomarker. Nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon match-pairs sign ranked test) were used to compare biomarker values prior to administration and following administration of BNC105. Median values for each biomarker (expressed as a ratio to pre-treatment concentrations) were used as the cut-points for stratification of patients into two groups which were then evaluated for correlation with the efficacy endpoint of 6 month PFS as previously described.(11) Time-to-event analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and results compared using log-rank test. All patients were given the option to submit tissue (either frozen or paraffin-embedded) from diagnostic or surgical procedures for RCC.

Clinical Assessments

Patients were assessed for safety by means of monitoring for adverse events (AEs) that were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0. Response was assessed using RECIST 1.0 criteria at baseline and after every third cycle. Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were defined as new or worsening AEs (both drug and non-drug related), which commenced or worsened, on or after the time of first administration of the study drug.

Statistical Analysis

As noted, the phase I component of the study utilized a classical 3+3 design to identify the MTD for phase II assessment. The primary endpoint of the randomized phase II trial was 6-month progression-free survival (6MPFS). With 61 patients per group, there was estimated to be 80% power to detect an improvement in 6MPFS from 36% on the control arm (everolimus alone) to 60% on the experimental arm (the combination of everolimus with BNC105P) using one-sided Chi-square test with continuity correction (α=0.05). A 6-month landmark was used to ascertain a clinical benefit more rapidly and facilitate a decision regarding further study of the combination. Patients were stratified by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk group (good, intermediate and poor) and number of prior regimens (1 or >1). Assuming roughly 10% of patients would be inevaluable for the primary endpoint, a target total enrollment of 134 patients was set.

Secondary endpoints in the phase I component of the study included PK parameters, which were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Secondary endpoints in the phase II component included cumulative progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), summarized using the Kaplan-Meier method, as well as overall response rate (ORR) and AEs.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

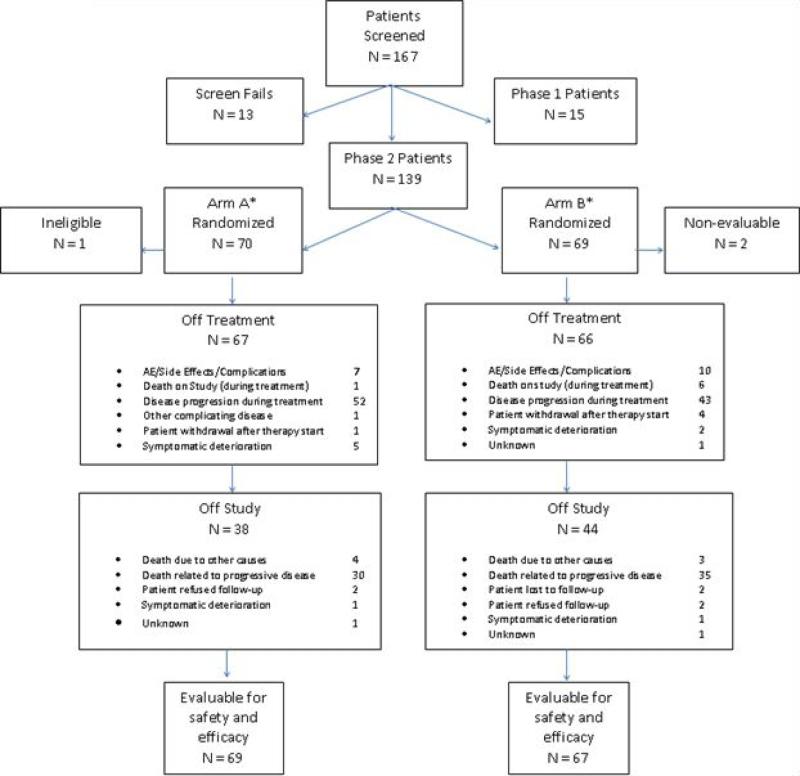

A total of 15 patients were enrolled in the phase I component. Twelve of the 15 patients completed at least 1 cycle of combination therapy, and the 3 patients who did not complete 1 cycle were replaced at the same dose level. The median age of this cohort was 62, with 9 male patients (60%) and 6 female patients (40%). The majority of the patients enrolled were white (13 patients, or 87%), and the remainder were African American. In the randomized phase II study, a total of 139 patients were randomized. One patient was deemed ineligible after randomization but before initiation of therapy – characteristics of the remaining 138 patients are listed in Table 1. Ultimately, 69 patients and 67 patients were evaluable for safety and efficacy in the combination therapy arm and everolimus monotherapy arm, respectively (Figure 1). Both treatment arms were balanced with respect to baseline demographic factors and clinicopathologic criteria. The median age of the overall study population was 63, with the majority (76%) being male. As in the phase I experience, the majority of patients were white (87%), and the majority of patients had a KPS ranging from 80-100 (93%). There was a similar distribution of patients by MSKCC risk group across treatment arms; approximately 24% of patients were characterized as good-risk, while 67% were characterized as intermediate risk. Only 9% of patients were noted to be poor-risk. The most frequent sites of metastasis amongst patients enrolled in the phase II study were: (1) lung (80%), (2) bone (33%), and liver (19%). The extent of prior therapy was similar between arms. Notably, nearly one-third of patients had received four or more prior treatments. With respect to the extent of prior VEGF-TKI therapy, 85% had received one prior VEGF-TKI, while the remainder received two.

Table 1.

Patient demographics in the phase II component of the DisrupTOR-1 study.

| Total (%) | Arm A (%) | Arm B (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | N=138 | N=69 | N=69 | 0.16 |

| Female | 33 (24) | 20 (29) | 13 (19) | |

| Male | 105 (76) | 49 (71) | 56 (81) | |

| Age (years) | 0.43 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62 (9) | 62 (9) | 63 (9) | |

| Median | 63 | 61 | 64 | |

| Minimum | 40 | 45 | 40 | |

| Maximum | 84 | 82 | 84 | |

| Race | 0.46 | |||

| White | 120 (87) | 61 (88) | 59 (86) | |

| Black or African American | 6 (4) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | |

| Asian | 10 (7) | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | |

| American Indian or Alaska | 1 (1) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Initial KPS | 0.46 | |||

| 100 | 54 (39) | 29 (42) | 25 (36) | |

| 90 | 47 (34) | 23 (33) | 24 (35) | |

| 80 | 28 (20) | 13 (19) | 15 (2) | |

| 70 | 9 (7) | 4 (6) | 5 (7) | |

| MSKCC Risk Group | 0.93 | |||

| Good | 33 (24) | 17 (24.64) | 16 (23.19) | |

| Intermediate | 92 (67) | 45 (65.22) | 47 (68.12) | |

| Poor | 13 (9) | 7 (10.14) | 6 (8.70) | |

| Metastatic Site | ||||

| Lung | 111 (80) | 57 (83) | 54 (78) | 0.52 |

| Liver | 26 (19) | 13 (19) | 13 (19) | >0.99 |

| Bone | 45 (33) | 21 (30) | 24 (35) | 0.59 |

| Brain | 8 (6) | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | 0.47 |

| Number of Prior Therapies | ||||

| 1 | 27 (20) | 14 (20) | 13 (19) | |

| 2 | 42 (30) | 24 (35) | 18 (26) | |

| 3 | 25 (18) | 10 (14) | 15 (22) | |

| ≥4 | 44 (32) | 21 (30) | 23 (33) |

(Note: Arm A = everolimus with BNC105P; Arm B = everolimus monotherapy.)

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram outlining overall study accrual. (Note: A CONSORT diagram reflecting patients receiving BNC105P monotherapy after progression on everolimus monotherapy is included in Supplementary Figure 2.) * Two patients remain on therapy in Arm A, and one patient remains on therapy in Arm B.

Phase I Study: Efficacy and Safety

No protocol-defined DLTs (drug-related, during Cycle 1) were observed in any of the phase I subjects and thus there was no expansion in any of the dose level cohorts outside of the highest dose level (16 mg/m2). Thus, the combination of everolimus at 10 mg oral daily with BNC105P at 16 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 on a 21 day cycle was identified as the recommended phase II dose (RP2D). Toxicities observed on study that were deemed to be drug-related (either single agent or combination) included single Grade 3 events of anemia and pericardial effusion. Grade 2 events (more than 1 occurrence) of fatigue, anemia and oral mucositis were also observed. TEAEs considered to have a potential causal relationship to either study drug (possibly, probably or definitely related to study drug) are listed in Supplementary Table 2. No objective responses were observed, but SD was observed in 8 patients with a median time on therapy of 11 cycles (33 weeks) and a range of 5-24 cycles.

Phase I Study: PK Results

PK analysis was performed on plasma from the 14 patients who received study treatment. The geometric mean half-life of BNC105P, averaged across all patients for both Day 1 and Day 8, was 0.08 hours (5 min). The geometric mean half-life of BNC105 was 0.32 hours (19 min). The elimination rate of BNC105 immediately post-dose appears to be first-order, with the rate becoming slower by 30 min post-dose. The concentration profiles were similar for the two treatment days. There was no trend observed in the plasma levels of either analyte between the Day 1 and Day 8 profiles, indicating no change in metabolism across the two administrations of the drug in Cycle 1.

Everolimus was administered daily in the evening. PK sampling was performed during clinic visits on the day of BNC105P administration. The mean concentration was approximately constant over the 6-hour collection interval, with an overall mean of 17.8 ng/mL. This value is consistent with previously reported results, where the half-life was reported as 26-38 hours, and the mean trough concentration at steady state was 13.2 ng/mL in patients who received 10 mg everolimus daily.(12)

Phase II Study: Efficacy and Safety

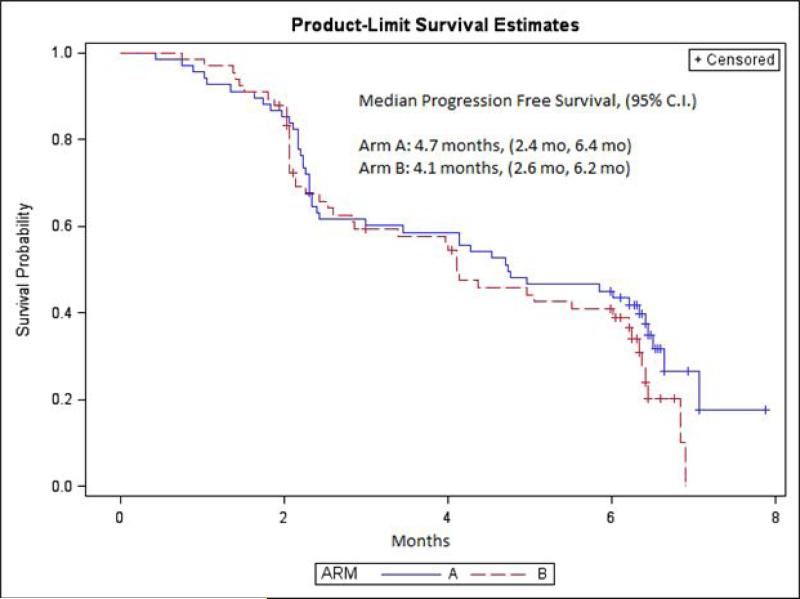

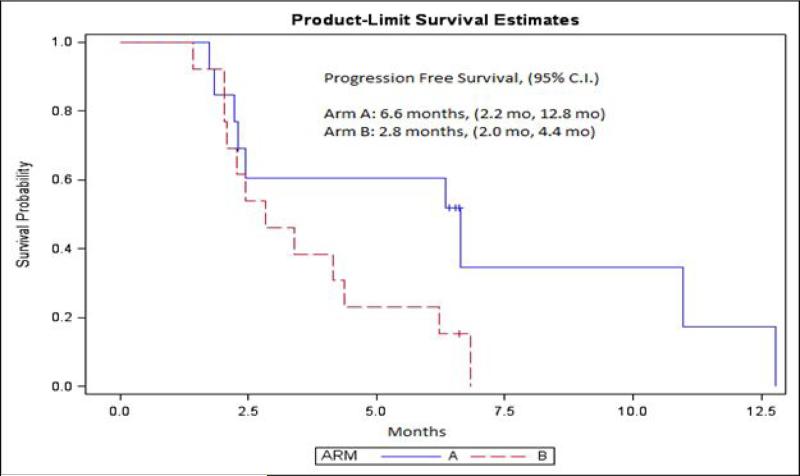

A mean of 7.46 and 6.01 cycles of combination therapy and everolimus monotherapy was rendered in each arm, respectively. At the time of last follow-up, the maximum number of cycles of combination therapy rendered was 31, as compared to 20 cycles of everolimus monotherapy. The primary outcome measure, 6MPFS, was similar in both study arms (33.82% with combination therapy versus 30.30% with everolimus monotherapy; P=0.66). One complete response and 1 partial response on combination therapy was observed, and 2 partial responses with everolimus monotherapy were observed. At the time of last follow-up, responses were ongoing for a duration in excess of 12 months. As depicted in Figure 2, there was no difference in median PFS. Furthermore, no differences were seen in median PFS amongst patient subgroups stratified by pre-specified criteria, including MSKCC risk score and number of prior VEGF-TKIs. In an exploratory analysis of clinical outcome based on sites of metastasis, an improvement in median PFS was seen with combination therapy amongst patients with liver metastasis (6.6 months versus 2.8 months, Figure 3). These results should be interpreted with caution, however, given the limited number of patients in the analysis.

Figure 2.

PFS with the combination of everolimus with BNC105P (Arm A) and everolimus monotherapy (Arm B).

Figure 3.

PFS with the combination of everolimus with BNC105P (Arm A) and everolimus monotherapy (Arm B) in an exploratory analysis of patients with liver metastasis.

A total of 33 patients were ultimately crossed over from everolimus monotherapy to monotherapy with BNC105P. The demographics of this population did not vary significantly from the overall study population – the median age of this group was 66, and 76% of the patients were male. Amongst 25 patients in this subset evaluable for response, SD was recorded as the best response in 20 patients (80%). Median time to progression was 1.8 months (95%CI 1.74-2.04) (Supplementary Figure 1).

AEs present in more than 10% of the study population in the phase II experience are shown in Table 2. The most frequent clinical AEs were fatigue, dyspnea, cough, diarrhea and mucositis. The most frequent laboratory abnormalities were hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia. Toxicities were similar in both treatment arms. As many of these toxicities (e.g., mucositis, dyspnea, elevated lipids and hyperglycemia) are frequently encountered with everolimus, it was felt that the majority of adverse events were attributable to everolimus as opposed to BNC105P. The majority of toxicities were grade 1/2.

Table 2.

Adverse events present in 10% or more of the study population in the phase II component of the DisrupTOR-1 study.

| Arm A (n=69) | Arm B (n=67) | Total (n=136) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | Total | % | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3/4 | Grade 5 | Total | % | N | % | |

| Clinical | ||||||||||||

| Fatigue | 28 | 3 | 0 | 31 | 44.9 | 24 | 6 | 0 | 30 | 44.8 | 61 | 44.9 |

| Dyspnea | 18 | 4 | 0 | 22 | 31.9 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 31.3 | 43 | 31.6 |

| Cough | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 31.9 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 20.9 | 36 | 26.5 |

| Diarrhea | 15 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 24.6 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 23.9 | 33 | 24.3 |

| Stomatitis | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 18.8 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 19 | 28.4 | 32 | 23.5 |

| Nausea | 12 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 20.3 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 23.9 | 30 | 22.1 |

| Lower extremity | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 23.2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 19.4 | 29 | 21.3 |

| Rash | 13 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 20.3 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 22.4 | 29 | 21.3 |

| Back pain | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 18 | 26.9 | 28 | 20.6 |

| Anorexia | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 13.0 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 23.9 | 25 | 18.4 |

| Constipation | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 22.4 | 25 | 18.4 |

| Skin changes | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 13.0 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 14 | 20.9 | 23 | 16.9 |

| Proteinuria | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.9 | 20 | 14.7 |

| Insomnia | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 16.4 | 19 | 14.0 |

| Extremity pain | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 13.4 | 19 | 14.0 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 16.4 | 19 | 14.0 |

| Fever | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 8.7 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 17.9 | 18 | 13.2 |

| Acneiform rash | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10.4 | 17 | 12.5 |

| Abdominal pain | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 13.0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 10.4 | 16 | 11.8 |

| Headache | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5.8 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 16.4 | 15 | 11.0 |

| Pruritus | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 7.5 | 15 | 11.0 |

| Taste alteration | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7.2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.9 | 15 | 11.0 |

| Epistaxis/Respiratory tract hemorrhage | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8.7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.9 | 14 | 10.3 |

| Laboratory | ||||||||||||

| Low hemoglobin | 20 | 9 | 0 | 29 | 42.0 | 19 | 6 | 0 | 25 | 37.3 | 54 | 39.7 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 24.6 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 28.4 | 36 | 26.5 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 11 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 21.7 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 31.3 | 36 | 26.5 |

| Hyperglycemia | 10 | 5 | 0 | 15 | 21.7 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 25.4 | 32 | 23.5 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 29.0 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 14.9 | 30 | 22.1 |

| Elevated alkaline phosphatise | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 14.9 | 18 | 13.2 |

| Elevated creatinine | 7 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 13.0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 11.9 | 17 | 12.5 |

| Elevated AST | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.9 | 16 | 11.8 |

| Hyponatremia | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 11.9 | 16 | 11.8 |

| Elevated ALT | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11.6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10.4 | 15 | 11.0 |

(Note: Arm A = everolimus with BNC105P; Arm B = everolimus monotherapy.)

Two deaths encountered with combination therapy were deemed potentially related to protocol-based therapy secondary to pneumonitis and infection, respectively. Given the lack of pneumonitis and infection seen in previous studies of BNC105P and the occurrence of these adverse events in previous studies of everolimus, they were presumably related to the latter.

Phase II Study: Biomarker Analysis

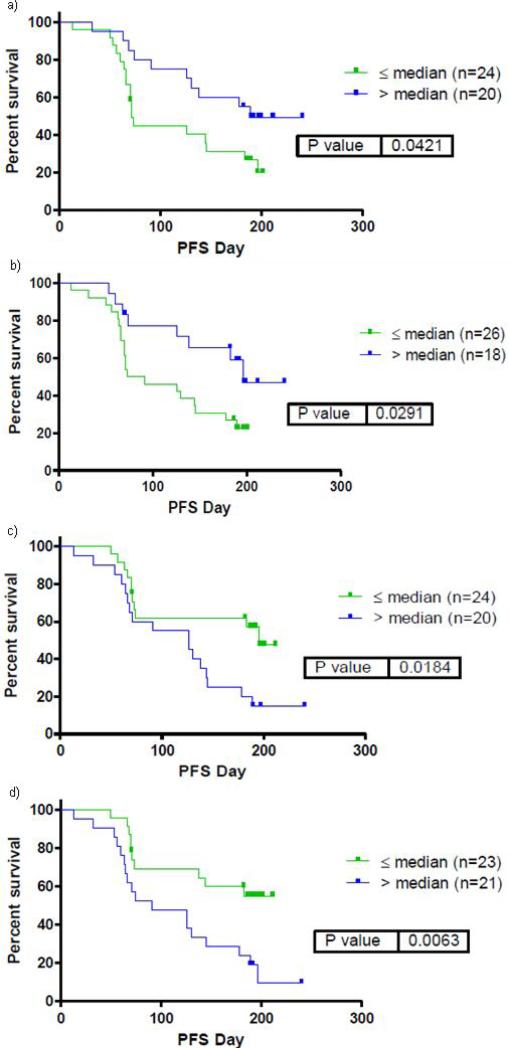

As noted in Methods, serum was collected for pre-specified biomarker analyses in patients receiving systemic therapy with BNC105P (both as combination therapy and as monotherapy following progression on everolimus alone). Blood was collected prior to and after administration of drug, and thus data presented herein reflects the change in biomarker level before and after drug administration. Significant associations were noted between the change in four biomarkers (above and below the median value) and PFS (Figure 4). Specifically, an increase in matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and stem cell factor (SCF) were associated with an improvement in PFS. Changes in MMP-9 correlated with changes in SCF. In contrast, a decrease in sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and serum amyloid P-component (SAP) were associated with improved PFS. Changes in SHBG correlated with changes in SAP. Patients that were progression free at 6 months correlated with increased MMP-9 and SCF or decreased SHBG and SAP. Selection of patients based on such changes in these four biomarkers enriches for patients that are progression free at 6 months (from 36% in the unselected population to 60% in the selected population).

Figure 4.

PFS in patients treated with everolimus with BNC105P stratified by change in serum biomarkers above or below median values. Serum biomarkers include MMP-9 (a), SCF (b), SHGB (c) and SAP (d).

DISCUSSION

The phase I component of the study identified a MTD of 16 mg/m2 for BNC105P in combination with the standard dose of everolimus, with no DLTs observed. Evaluation in the randomized phase II setting suggested no significant difference in 6MPFS with the combination of everolimus and BNC105P as compared to everolimus monotherapy. Furthermore, no significant differences in cumulative PFS, OS, and ORR were seen. Notably, it did not appear that BNC105P added substantially to the toxicity profile of everolimus, with most toxicities seen with combination therapy attributable to the latter. Exploratory biomarker analyses identified associations between clinical outcome with combination therapy and MMP-9, SCF, SAP and SHBG. Thus, although the study failed to meet its primary endpoint, further exploration of these correlative results (perhaps in the context of a biomarker-driven trial) might be warranted.

There is currently equipoise regarding the optimal second-line treatment of mRCC after failure of first-line VEGF-directed agents. The strategy of combination therapy is one of three potential avenues to improving outcomes in pre-treated patients. A second potential option is to evaluate novel therapies in comparative designs. Impressive early data for the programmed death-1 inhibitor nivolumab has led to a phase III comparison of nivolumab versus everolimus in the second-line setting.(13-15) Similarly, encouraging data from a phase I trial evaluating the dual VEGFR2/MET inhibitor cabozantinib in patients with mRCC has led to a phase III study also directly comparing the agent to everolimus.(16, 17) Notably, even if these studies are positive and result in therapeutic approval, everolimus will remain a part of the therapeutic continuum. Thus, the approach of evaluating combinations that may enhance the activity of the drug remains valid.

The third potential avenue is evaluation of therapies in prospective biomarker-based trials. In the current study, changes in several serum biomarkers with BNC105P therapy have been associated with improved clinical outcome – prior to this study, biomarkers related to VDA response have been poorly characterized. Increased expression of MMP-9 correlates with poor prognostic variables in patients with RCC, and may predict metastasis in patients with localized disease.(18-20) From a mechanistic standpoint, MMP-9 may contribute to increased tumor angiogenesis.(21) SCF binds to c-Kit, a putative target of VEGF-TKIs such as sorafenib.(22) Several studies have shown a correlation between clinical outcome and SCF, and mutations in the substrate binding pocket of SCF have been implicated in conferring resistance to TKIs.(23, 24) Less is known about the mechanistic role of the remaining two biomarkers, SAP and SHBG, in the pathogenesis of RCC, although some studies have suggested a prognostic role of SAP in the disease.(25) In an exploratory analysis, the four biomarkers noted herein were assessed in combination to generate a potential signature for response. With selection of patients that had (1) a rise in MMP-9 and SCF and (2) a fall in SHGB and SAP, approximately 60% of patients were progression free at 6 months. Amongst patients that failed to meet this definition, only 5% were progression free at 6 months. In a prospective trial of everolimus with BNC105P, one could envision enriching the study for those patients who meet this stringent biomarker characterization after a test dose of BNC105P.

Several limitations of the reported study should be noted. First, although the intent of the study was to transition patients receiving everolimus monotherapy to BNC105P monotherapy, this crossover did not take place in the majority of patients. This limits the ability to infer any potential benefit of BNC105P in the everolimus-refractory patient. Second, there was significant heterogeneity in the number of prior lines of therapy rendered. With nearly one-third of patients receiving four or more prior systemic treatments, it is challenging to ascertain whether imbalances in this regard may have led to the null difference in the treatment arms. Third, the study aimed to demonstrate an improvement in 6MPFS, a somewhat uncharacteristic primary endpoint amongst studies in mRCC. Although this may be a moot point given a lack of significant differences in other clinical outcomes (e.g., PFS, OS, and ORR), selection of a different endpoint may have impacted the design and enrollment of the study. The investigators felt 6MPFS to be justified given data from the phase III AXIS and RECORD-1 trials, evaluating axitinib and everolimus, respectively. When specifically considering the subset of patients with one prior VEGF-TKI, a median PFS of 4.8 and 5.4 months were observed, respectively. Finally, a major limitation of the noted biomarker analyses is no blood was collected on the control arm (everolimus alone) at baseline. As noted, the protocol stipulated blood collection at the start of therapy with the combination of agents or with BNC105P monotherapy. Of note, further correlative studies are underway using tissue collected from both control and experimental arms using the NanoString multigene assay, a platform that has been applied in several other malignancies.(26, 27) In contrast to the serum studies reported herein, by inclusion of specimens from the control arm, these studies may be both prognostic and predictive.

Despite these limitations, the current study adds to a relatively scant literature documenting the activity of an investigational compound in concert with everolimus. There have been previous unsuccessful attempts to demonstrate a benefit with the combination of VEGF-and mTOR-directed treatments for mRCC. The RECORD-2 trial, for instance, compared the combination of bevacizumab and everolimus to the standard combination of bevacizumab with IFN-α.(5) The study failed to meet its primary endpoint, showing no difference in PFS with the two regimens. The randomized phase III INTORACT trial compared bevacizumab and temsirolimus (an intravenous mTOR inhibitor) with bevacizumab with IFN-α, and similarly showed no significant difference in clinical outcome.(4) Although the DisrupTOR-1 trial showed no benefit with the addition of BNC105P to everolimus in the overall study population, a narrower assessment in a biomarker-driven population may be a potential avenue forward for this agent.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELAVANCE.

Everolimus represents a standard treatment employed after failure of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-directed therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). The current phase I/II study explores the combination of everolimus with the novel vascular disrupting agent BNC105P. Although the study failed to meet its primary endpoint, correlative studies done in association with this trial suggest that there might be a subset of patients that derive benefit from combination therapy. These patients are defined by dynamic biomarkers including matrix metalloproteinase-9, stem cell factor, sex hormone binding globulin and serum amyloid A protein. A prospective study is under development that will explore everolimus with BNC105P in a biomarker-defined subpopulation of patients.

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

S.K. Pal receives consulting fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Aveo and Bionomics.

REFERENCES

- 1. [March 21, 2014];National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines: Renal Cell Carcinoma. (Available at http://www.nccn.org.)

- 2.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1931–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Bellmunt J, Clancy J, Wang K, Niethammer AG, Hariharan S, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Temsirolimus and Bevacizumab Versus Interferon Alfa and Bevacizumab in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: INTORACT Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:752–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravaud A, Barrios C, Anak Ö , Pelov D, Louveau A, Alekseev B, et al. Randomized phase II study of first-line everolimus (EVE) + bevacizumab (BEV) versus interferon alfa-2a (IFN) + BEV in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): RECORD-2. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012;23 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv170. [Abstr 7830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng F, Cai X, Duan J, Matteucci M, Hart C. A novel class of tubulin inhibitors that exhibit potent antiproliferation and in vitro vessel-disrupting activity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:953–63. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremmidiotis G, Leske AF, Lavranos TC, Beaumont D, Gasic J, Hall A, et al. BNC105: A Novel Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitor That Selectively Disrupts Tumor Vasculature and Displays Single-Agent Antitumor Efficacy. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:1562–73. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inglis DJ, Lavranos TC, Beaumont DM, Leske AF, Brown CK, Hall AJ, et al. The vascular disrupting agent BNC105 potentiates the efficacy of VEGF and mTOR inhibitors in renal and breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1–9. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.956605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis L, Shah P, Hammers H, Lehet K, Sotomayor P, Azabdaftari G, et al. Vascular Disruption in Combination with mTOR Inhibition in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2012;11:383–92. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rischin D, Bibby DC, Chong G, Kremmidiotis G, Leske AF, Matthews CA, et al. Clinical, Pharmacodynamic, and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of BNC105P: A Phase I Trial of a Novel Vascular Disrupting Agent and Inhibitor of Cancer Cell Proliferation. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:5152–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyvanjah K, DePrimo SE, Harmon CS, Huang X, Kern KA, Carley W. Soluble KIT correlates with clinical outcome in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with sunitinib. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:165. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA, 3rd, Rea D, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shand N, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1588–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Feburary 20, 2014]; NCT01668784: Study of Nivolumab (BMS-936558) vs. Everolimus in Pre-Treated Advanced or Metastatic Clear-cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (CheckMate 025) (Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.)

- 14.Choueiri TK, Fishman MN, Escudier BJ, Kim JJ, Kluger HM, Stadler WM, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of nivolumab in previously treated and untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Biomarker-based results from a randomized clinical trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014:32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Redman BG, Kuzel T, Harrison MR, et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Results of a randomized, dose-ranging phase II trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014:32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choueiri TK, Kumar Pal S, McDermott DF, Morrissey S, Ferguson KC, Holland J, et al. A phase I study of cabozantinib (XL184) in patients with renal cell cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [February 20, 2014]; NCT01865747: A Study of Cabozantinib (XL184) vs Everolimus in Subjects With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (METEOR) (Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov)

- 18.Slaton JW, Inoue K, Perrotte P, El-Naggar AK, Swanson DA, Fidler IJ, et al. Expression levels of genes that regulate metastasis and angiogenesis correlate with advanced pathological stage of renal cell carcinoma. The American journal of pathology. 2001;158:735–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallakury BV, Karikehalli S, Haholu A, Sheehan CE, Azumi N, Ross JS. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 1 and 2 correlate with poor prognostic variables in renal cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7:3113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawata N, Nagane Y, Igarashi T, Hirakata H, Ichinose T, Hachiya T, et al. Strong significant correlation between MMP-9 and systemic symptoms in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;68:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Yamashita M, Uetsuki H, Kakehi Y. Angiogenesis in renal cell carcinoma: Evaluation of microvessel density, vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases. International journal of urology. 2002;9:509–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith RA, et al. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2006;5:835–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoernig I, Ziegelmeier C, Lahrmann B, Grabe N, Jager D, Halama N. Sequence mutations of the substrate binding pocket of stem cell factor and multidrug resistance protein ABCG2 in renal cell cancer: a possible link to treatment resistance. Oncology reports. 2013;29:1697–700. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marech I, Gadaleta CD, Ranieri G. Possible Prognostic and Therapeutic Significance of c-Kit Expression, Mast Cell Count and Microvessel Density in Renal Cell Carcinoma. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014;15:13060–76. doi: 10.3390/ijms150713060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood SL, Rogers M, Cairns DA, Paul A, Thompson D, Vasudev NS, et al. Association of serum amyloid A protein and peptide fragments with prognosis in renal cancer. British journal of cancer. 2010;103:101–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beard RE, Abate-Daga D, Rosati SF, Zheng Z, Wunderlich JR, Rosenberg SA, et al. Gene expression profiling using nanostring digital RNA counting to identify potential target antigens for melanoma immunotherapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:4941–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Sohn I, Do IG, Kim KM, Park SH, Park JO, et al. Nanostring-based multigene assay to predict recurrence for gastric cancer patients after surgery. PloS one. 2014;9:e90133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.