Abstract

Background

Microsatellite instability (MSI) and BRAF-mutation status are associated with colorectal cancer survival whereas the role of body mass index (BMI) is less clear. We evaluated the association between BMI and colorectal cancer survival, overall and by strata of MSI, BRAF-mutation, sex, and other factors.

Methods

This study included 5,615 men and women diagnosed with invasive colorectal cancer who were followed for mortality (maximum: 14.7 years; mean: 5.9 years). Pre-diagnosis BMI was derived from self-reported weight approximately 1-year before diagnosis and height. Tumor MSI and BRAF-mutation status were available for 4,131 and 4,414 persons, respectively. Multivariable hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from delayed-entry Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

In multivariable models, high pre-diagnosis BMI was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality in both sexes (per 5-kg/m2, HR = 1.10; 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.15), with similar associations stratified by sex (p-interaction: 0.41), colon vs rectum (p-interaction: 0.86), MSI status (p-interaction: 0.84), and BRAF-mutation status (p-interaction: 0.28). In joint models, with MS-stable/MSI-low and normal BMI as the reference group, risk of death was higher for MS-stable/MSI-low and obese BMI (HR: 1.32; p-value: 0.0002), not statistically significantly lower for MSI-high and normal BMI (HR: 0.86; p-value: 0.29), and approximately the same for MSI-high and obese BMI (HR: 1.00; p-value: 0.98).

Conclusions

High pre-diagnosis BMI was associated with increased mortality; this association was consistent across participant subgroups, including strata of tumor molecular phenotype.

Impact

High BMI may attenuate the survival benefit otherwise observed with MSI-high tumors.

Keywords: obesity, microsatellite instability, survival, BRAF mutation, colon cancer

Introduction

High body mass index (BMI) is an established risk factor for colorectal cancer (1–4); however, associations are usually stronger for men than women and for colon than rectal cancers (2–5). Emerging data suggest the BMI-colorectal cancer association differs by microsatellite instability (MSI) status (6–10), with stronger associations typically shown for MS-stable than MSI-high tumors and other tumor phenotypes correlated with MS-stable (11). The impact of BMI on mortality after colorectal cancer diagnosis is less clear, possibly owing to the timing of BMI evaluation relative to diagnosis (12–15). When BMI was evaluated in the peri- or post-diagnosis period, generally null or only modest associations were shown (10, 12–14, 16–23). In contrast, when pre-diagnosis BMI was evaluated, studies typically showed higher risks of all-cause and colorectal-cancer-specific mortality with high BMI (12–15, 24–26).

MSI is an established marker of colorectal cancer survival: patients with MSI-high tumors have a favorable prognosis compared to age- and stage-matched patients with MS-stable tumors (27–29). Similarly, patients with BRAF mutations, compared to patients with BRAF-wildtype tumors, have poorer prognosis (29, 30). It is not known if BMI or other lifestyle and behavioral factors modify the influences of MSI or BRAF on survival; it is plausible that lifestyle factors, including BMI, may differentially influence survival of patients according to tumor molecular features since those factors likely interact with the tumor cells’ microenvironment.

Sub-group differences for the association between BMI and colorectal cancer incidence are consistently shown by strata of sex, site in the colorectum, and tumor molecular phenotype; however, it is not clear if these etiologic differences translate to the prognosis setting. This study examined the associations of BMI 2 years prior to enrollment (which is akin to BMI approximately 1 year prior to diagnosis, and referred to here as ‘pre-diagnosis recent BMI’), BMI at age 20 years, and adult weight change with all-cause and colorectal-cancer-specific mortality in a cohort of 5,615 adults who were diagnosed with incident, invasive colon or rectal adenocarcinoma. Additionally, we examined whether associations differed by strata of sex, tumor site in the colorectum, smoking, disease stage, MSI, BRAF, and other factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Men and women in this study were identified from the Colon-Cancer Family Registry (Colon-CFR), an international resource for studies on colorectal cancer etiology and survival, initiated in 1997 (31). Case participants with incident colon or rectal cancer were identified via state or provincial cancer registries and invited to enroll. The mean time from diagnosis to enrollment for persons in this analysis was 0.92 years.

Of the 7,702 persons initially identified in the Colon-CFR that had returned an epidemiologic questionnaire, exclusions were made as follows: diagnosis prior to baseline in 1997 (n=97); primary diagnosis with appendiceal or intestinal not-otherwise-specified cancer (n = 56); carcinoma in situ (n=29); missing age or date of enrollment (n=8); missing pre-diagnosis recent BMI (n=152); missing end-of-follow-up date (n=121); proxy respondent (n=124); less than 30 days of follow-up time (n=365); and time from diagnosis to enrollment greater than 2 years (n=1,135). Thus, 5,615 Colon-CFR enrollees were included in this analysis.

Data Collection

Data on demographics, race/ethnicity, personal and family history of cancer, medical history, reproductive factors, physical activity, diet, alcohol, tobacco, body weight, and height were collected via standardized personal interviews, telephone interviews, and/or mailed questionnaires (8, 31). The questionnaires are available online (32). Two measures of self-reported body weight were requested: pre-diagnosis recent weight (queried as body weight 2 years prior to enrollment, which corresponds to approximately 1 year prior to cancer diagnosis) and weight at age 20 years. All persons were asked to provide current height. All co-variables used a pre-diagnosis referent period. After enrollment, the cohort was actively followed via periodic contact. Vital status, cause of death (COD), and date of death were ascertained through linkage with population-based registries, accrual of death certificates, contact with next-of-kin, and, more rarely, via other mechanisms (e.g., obituaries).

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and the institutional review boards at each center approved the studies.

Assessment of BMI and Adult Weight Change

Pre-diagnosis recent BMI was calculated from pre-diagnosis recent weight in kilograms (kg) divided by height in meters (m) squared; BMI at age 20 years was similarly calculated using weight at age 20 years. BMI was categorized according to World Health Organization criteria (33). Adult weight change was calculated as pre-diagnosis recent weight minus weight at age 20 years (both in kg).

Assessment of Tumor Characteristics

Tumor tissue from the Jeremy Jass Memorial Pathology Bank characterized the tumor MSI and BRAF mutational status of 4,131 and 4,414 persons, respectively. Persons without MSI (n = 1,484) were, on average, younger than those with tumor blocks (mean age at study enrollment: 53.2 vs 55.9 years; P<.0001); otherwise, there were no meaningful differences between those with and without MSI by sex, site, disease stage, or BMI. BRAF data were available for slightly more persons diagnosed with colon (79.8%) than rectal (76.3) cancer (P=0.003); otherwise no meaningful differences were noted.

DNA for molecular testing was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues with use of the QIAamp Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described (8). For the majority of case subjects with MSI (n=2,893), tumor MSI was assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays with the use of four mononucleotide markers (BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, and BAT34C4), five dinucleotide markers (D5S346, D17S250, ACTC, D18S55, and D10S197), and one complex marker (MYCL) (8). Tumors were classified as MSI-high if ≥30% of the markers demonstrated instability (i.e., a change in marker repeat length was detected when comparing DNA from normal to tumor tissue), MSI-low if >0% and <30% demonstrated instability, and MS-stable if none exhibited instability (34). A minimum of four unequivocal results were required to characterize MSI. For a minority of persons (n=1,238), MSI status was determined via immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the mismatch repair proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. Positive staining for all proteins indicated MS-stable whereas absence of staining for any protein indicated MSI-high (35, 36). IHC-based methods for detecting MSI-high and MS-stable show very high sensitivity and specificity with PCR-based methods (35). Tumor DNA was used to assess the BRAF c.1799 T>A (p.V600E) mutation using fluorescent allele-specific PCR, as described previously (37).

Colorectal cancer stage at the time of diagnosis was collected from state/provincial cancer registry information and/or from clinical/pathology records. When stage data were available both from registries and clinical/pathology records, the latter took precedence. Harmonized summary stage data were derived according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) criteria (38) or converted from SEER summary stage to TNM summary stage using an algorithm (39). Participants who were missing one or more of the individual components required to derive TNM summary stage (i.e., depth of invasion of the primary tumor, T-stage; presence of metastases in regional lymph nodes, N-stage; and presence of distant metastases, M-stage) were set to missing stage (20.7%).

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using delayed-entry Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the associations of pre-diagnostic BMI and adult weight change with risk of death. Delayed-entry models accounted for the lag between diagnosis and enrollment. The time axis for all analyses was time since diagnosis and models were stratified on age at diagnosis. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with multiplicative interaction terms between BMI and time and Cox models with and without interaction terms were compared via the likelihood ratio test. Fully-adjusted models included smoking status, tumor stage, study center, and sex (combined models), as parameterized in Table 1. Missing covariables were treated as a separate category. Inclusion of physical activity, red meat intake, education, race, and aspirin made no appreciable differences to the HRs and were not included in the final models. Follow-up time ended with date of death or last contact.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort overall and by strata of pre-diagnosis recent body mass index (BMI)*.

| Categories | Total (N=5,615) | Pre-diagnosis recent BMI

|

p-value** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 (N=83) | 18.5–<25 (N=1,897) | 25–<30 (N=2,152) | ≥30 (N=1,483) | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age at Diagnosis, years | ||||||

| <40 | 559 (10) | 22 (26.5) | 244 (12.9) | 186 (8.6) | 107 (7.2) | p < 0.0001 |

| 40 to <50 | 1,800 (32.1) | 26 (31.3) | 663 (34.9) | 620 (28.8) | 491 (33.1) | |

| 50 to <60 | 1,339 (23.8) | 6 (7.2) | 387 (20.4) | 531 (24.7) | 415 (28) | |

| 60 to <70 | 1,312 (23.4) | 15 (18.1) | 392 (20.7) | 553 (25.7) | 352 (23.7) | |

| ≥70 | 605 (10.8) | 14 (16.9) | 211 (11.1) | 262 (12.2) | 118 (8) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 2,928 (52.1) | 17 (20.5) | 733 (38.6) | 1,367 (63.5) | 811 (54.7) | p < 0.0001 |

| Women | 2,687 (47.9) | 66 (79.5) | 1,164 (61.4) | 785 (36.5) | 672 (45.3) | |

| Self-identified race | ||||||

| White | 4,549 (81) | 67 (80.7) | 1,506 (79.4) | 1,787 (83) | 1,189 (80.2) | p < 0.0001 |

| Black or African American | 376 (6.7) | 3 (3.6) | 78 (4.1) | 140 (6.5) | 155 (10.5) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 20 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) | 10 (0.5) | 8 (0.5) | |

| More than one race | 162 (2.9) | 1 (1.2) | 63 (3.3) | 49 (2.3) | 49 (3.3) | |

| Unknown, other, or not reported | 508 (9) | 12 (14.5) | 248 (13.1) | 166 (7.7) | 82 (5.5) | |

| Education† | ||||||

| Less than high school | 841 (15) | 13 (15.7) | 244 (12.9) | 348 (16.2) | 236 (15.9) | p < 0.0001 |

| High school graduate | 1,296 (23.1) | 17 (20.5) | 404 (21.3) | 490 (22.8) | 385 (26) | |

| Vocational/technical school | 1,865 (33.2) | 30 (36.1) | 610 (32.2) | 691 (32.1) | 534 (36) | |

| Undergraduate or graduate | 1,573 (28) | 22 (26.5) | 624 (32.9) | 609 (28.3) | 318 (21.4) | |

| Missing | 40 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 15 (0.8) | 14 (0.7) | 10 (0.7) | |

| Smoking Status‡ | ||||||

| Never | 2,357 (42) | 33 (39.8) | 851 (44.9) | 860 (40) | 613 (41.3) | p < 0.0001 |

| Former | 2,056 (36.6) | 14 (16.9) | 595 (31.4) | 870 (40.4) | 577 (38.9) | |

| Current | 1,096 (19.5) | 35 (42.2) | 421 (22.2) | 389 (18.1) | 251 (16.9) | |

| Missing | 106 (1.9) | 1 (1.2) | 30 (1.6) | 33 (1.5) | 42 (2.8) | |

| Red Meat Intake§ | ||||||

| <2 servings/week | 787 (14) | 22 (26.5) | 325 (17.1) | 276 (12.8) | 164 (11.1) | p <0.0001 |

| 2 or 3 servings/week | 1,963 (35) | 26 (31.3) | 696 (36.7) | 757 (35.2) | 484 (32.6) | |

| >3 to 5 servings/week | 1,262 (22.5) | 17 (20.5) | 403 (21.2) | 499 (23.2) | 343 (23.1) | |

| >5 servings/week | 1,347 (24) | 14 (16.9) | 367 (19.3) | 533 (24.8) | 433 (29.2) | |

| Missing | 256 (4.6) | 4 (4.8) | 106 (5.6) | 87 (4) | 59 (4) | |

| Physical Activity|| | ||||||

| 0 to 6 METs/week | 1,207 (21.5) | 18 (21.7) | 358 (18.9) | 446 (20.7) | 385 (26) | p <0.0001 |

| 6.1 to 20 METs/week | 765 (13.6) | 15 (18.1) | 261 (13.8) | 272 (12.6) | 217 (14.6) | |

| 20.1 to 44 METs/week | 1,614 (28.7) | 21 (25.3) | 583 (30.7) | 649 (30.2) | 361 (24.3) | |

| >44 METs/week | 1,510 (26.9) | 20 (24.1) | 537 (28.3) | 604 (28.1) | 349 (23.5) | |

| Missing | 519 (9.2) | 9 (10.8) | 158 (8.3) | 181 (8.4) | 171 (11.5) | |

| Colon or rectal site# | ||||||

| Colon | 3,713 (66.1) | 57 (68.7) | 1,234 (65.1) | 1,402 (65.1) | 1,020 (68.8) | p = 0.08 |

| Rectum | 1,902 (33.9) | 26 (31.3) | 663 (34.9) | 750 (34.9) | 463 (31.2) | |

| TNM Summary Stage** | ||||||

| I | 1,205 (21.5) | 21 (25.3) | 424 (22.4) | 475 (22.1) | 285 (19.2) | p = 0.28 |

| II | 1,210 (21.5) | 18 (21.7) | 416 (21.9) | 468 (21.7) | 308 (20.8) | |

| III | 1,431 (25.5) | 17 (20.5) | 459 (24.2) | 565 (26.3) | 390 (26.3) | |

| IV | 609 (10.8) | 8 (9.6) | 205 (10.8) | 214 (9.9) | 182 (12.3) | |

| Missing | 1,160 (20.7) | 19 (22.9) | 393 (20.7) | 430 (20.0) | 318 (21.4) | |

| MSI Status | ||||||

| MS-stable | 3,226 (57.5) | 50 (60.2) | 1,114 (58.7) | 1,239 (57.6) | 823 (55.5) | p = 0.41 |

| MSI-low | 317 (5.6) | 4 (4.8) | 109 (5.7) | 124 (5.8) | 80 (5.4) | |

| MSI-high | 588 (10.5) | 6 (7.2) | 210 (11.1) | 215 (10) | 157 (10.6) | |

| Missing | 1,484 (26.4) | 23 (27.7) | 464 (24.5) | 574 (26.7) | 423 (28.5) | |

| BRAF | ||||||

| Wild Type | 4,018 (71.6) | 57 (68.7) | 1,368 (72.1) | 1,545 (71.8) | 1,048 (70.7) | p = 0.96 |

| Mutation | 396 (7.1) | 6 (7.2) | 135 (7.1) | 149 (6.9) | 106 (7.1) | |

| Missing | 1,201 (21.4) | 20 (24.1) | 394 (20.8) | 458 (21.3) | 329 (22.2) | |

Derived from pre-diagnosis recent body weight (defined as “weight 2 years prior to enrollment”) in kg divided by height in meters squared.

χ2 test for differences across strata.

Defined as the highest completed level of education.

Cigarette smoking was defined as ever smoking one cigarette per day for 3 months or longer. Current smoking was indicated when the participant smoked cigarettes in the period two years prior to enrollment (referent period); former smoking was indicated when smoking stopped before the referent period.

One serving was defined as two to three ounces. Examples of red meat included beef, steak, hamburger, prime rib, and ham.

Derived from responses to total years, total months, and duration per week of nine modes of activity for three periods of the lifespan (20–29, 30–49, 50 years or older).

According to International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition anatomical site codes: C180, C182, C183, C184, C185, C186, C187, C188, C189, C260 (colon); C199, C209 (rectum).

Derived according to American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) criteria or converted from SEER summary stage to TNM summary stage.

For analyses of colorectal-cancer-specific mortality, follow-up time ended on the date of death from colon or rectal cancer as the primary underlying cause; persons who died from other causes or who were alive at last contact were censored in these analyses. Persons with unknown COD, and all persons enrolled in the USC/Stanford consortium (where no COD data were available), were excluded from the cause-specific analyses.

In categorical Cox models, persons who were underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2) were compared to persons with normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2). Obesity was further stratified as classes I (30–34.9 kg/m2), II (35–39.9 kg/m2), and III (≥40 kg/m2) when the number of outcomes was greater than or equal to 10 per BMI category. Linear models examined the association of BMI, in 5 kg/m2 increments, with mortality, excluding the underweight category. Wald tests assessed linear trends. Restricted cubic splines assessed potential non-linearity of the relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality (40). For the cubic spline analysis, knots were selected at BMI values of 18.5, 22, 25, 30 and 40 while the referent was set at 22. The likelihood ratio test assessed non-linearity via a model that contained only the linear term to a model with the linear and the cubic spline terms. Multiplicative interaction terms and the likelihood ratio test assessed whether the association between BMI and mortality differed by sex, MSI, BRAF, tumor site, smoking, and other factors. In sensitivity analyses, persons who were missing stage data were excluded. All P-values were two-sided; P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In this cohort, 2,053 deaths occurred (1,233 deaths attributed to colorectal cancer, 533 deaths attributed to other causes; COD was unavailable for 287 deaths) during a mean of 5.9 years from study enrollment to end-of-study (minimum: 31 days; maximum: 14.7 years). Of the 2,053 deaths, the majority were verified through linkage with various population-based registries or accrual of death certificates (n=1,401, 68%) while the remaining deaths were identified via next-of-kin contact (n=389, 19%) or through other mechanisms, including review of obituaries (n=263, 13%). As anticipated, MSI-high compared to MS-stable/MSI-low was associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.57 to 0.81), adjusted for stage, age, sex, BMI, smoking and study center, whereas BRAF-mutation compared to BRAF-wildtype was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.10 to 1.59), adjusted for MSI-status, stage, age, sex, BMI, smoking and study center.

Table 1 shows socio-demographic, pre-diagnostic behavioral/lifestyle factors, and clinical factors for the study sample overall and stratified by pre-diagnosis recent BMI. Persons who were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2), compared to persons who had normal BMI (18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2), were more likely to be men, ate more red meat, were less educated, were less likely to be current smokers, and were less physically active.

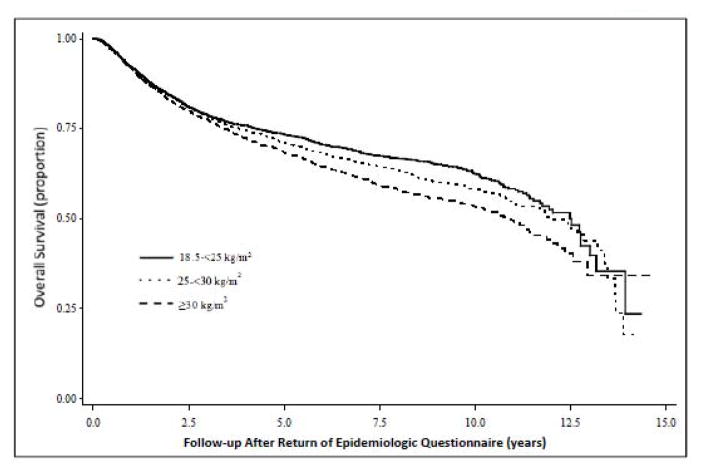

When testing the proportional hazards assumption, an interaction was observed for categorical BMI (excluding underweight BMI) and time (P: 0.003); however, after excluding the first 2 years of follow-up, the P-value for the interaction was no longer statistically significant. From visually inspecting the Kaplan-Meier curves for categorical pre-diagnosis recent BMI (Figure 1), it appears that the interaction between BMI and time is caused in the first 2 years of follow-up wherein the survival curves for the BMI categories essentially overlap. After approximately 2 or 3 years of follow-up, the curves begin to diverge, with the obese category showing the most marked decline (log rank p-value: <0.0001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for death from all-causes for men and women diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the Colon Cancer Family Registry, 1997 to 2012.

Table 2 shows the associations of pre-diagnosis recent BMI, BMI at age 20 years, and adult weight change with all-cause and colorectal-cancer-specific mortality. For women and men combined, there was a clear dose-response association between pre-diagnosis recent BMI and all-cause mortality: compared to a normal BMI, overweight, class I obesity, class II obesity, and class III obesity were associated with 12%, 19%, 43% and 52% higher risks of mortality from all causes, respectively. The same general pattern was shown for BMI at age 20 years and all-cause mortality, albeit with less precision. Adult weight change, per 5 kg, was associated with a marginally higher risk of all-cause mortality. Generally similar results were obtained for colorectal-cancer-specific mortality, although confidence intervals were wider with the smaller numbers of outcomes.

Table 2.

All-cause and colorectal-cancer-specific mortality for persons with colorectal cancer by pre-diagnosis BMI and weight change: the Colon-Cancer Family Registry, 1997 to 2012.

| Men and women combined

|

Women

|

Men

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths/Person years |

Multivariable HR (95% CI) * |

P- trend† |

P- interaction with sex‡ |

Deaths/Person years |

Multivariable HR (95% CI)* |

P- trend† |

Deaths/Person years |

Multivariable HR (95% CI)* |

P-trend† | |

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||||

| BMI Recent | ||||||||||

| <18.5 | 39/429 | 1.62 (1.15–2.28) | 31/351 | 1.76 (1.18–2.61) | -- | -- | ||||

| 18.5–<25 | 629/11,420 | 1.00 (ref) | 360/7,104 | 1.00 (ref) | 269/4,316 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 25–<30 | 787/12,842 | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) | 257/4,804 | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) | 530/8,037 | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | ||||

| ≥30 | 598/8,522 | 1.29 (1.14–1.45) | 0.36 | 259/3,828 | 1.33 (1.12–1.58) | 339/4,695 | 1.23 (1.04–1.46) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 30–<35 | 364/5,654 | 1.19 (1.04–1.37) | 130/2,170 | 1.25 (1.01–1.54) | 234/3,484 | 1.16 (0.96–1.39) | ||||

| 35–<40 | 141/1,790 | 1.43 (1.18–1.73) | 68/1,003 | 1.31 (1.00–1.73) | 73/786 | 1.59 (1.21–2.09) | ||||

| ≥40 | 93/1,079 | 1.52 (1.21–1.90) | 0.39 | 61/654 | 1.63 (1.21–2.19) | 32/425 | 1.19 (0.81–1.74) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Per 5 kg/m2§ | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) | <0.0001 | 0.41 | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | 0.0002 | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 0.004 | |||

| BMI at age 20 y | ||||||||||

| <18.5 | 130/2,213 | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | 93/1,655 | 1.04 (0.83–1.31) | 37/558 | 1.16 (0.82–1.63) | ||||

| 18.5–<25 | 1,342/23,556 | 1.00 (ref) | 645/12,301 | 1.00 (ref) | 697/11,255 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 25–<30 | 400/5,566 | 1.22 (1.08–1.37) | 90/1,349 | 1.24 (0.98–1.56) | 310/4,216 | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | ||||

| ≥30 | 116/1,228 | 1.57 (1.28–1.91) | 0.08 | 47/417 | 2.02 (1.47–2.78) | 69/811 | 1.32 (1.01–1.71) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 30–<35 | 90/956 | 1.67 (1.34–2.09) | 34/303 | 2.07 (1.44–2.98) | 56/652 | 1.48 (1.11–1.98) | ||||

| ≥35 | 26/272 | 1.27 (0.85–1.91) | 0.09 | 13/113 | 1.89 (1.03–3.47) | 13/159 | 0.86 (0.48–1.55) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Per 5 kg/m2§ | 1.10 (1.04–1.16) | 0.0007 | 0.002 | 1.23 (1.12–1.35) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.4 | |||

| Adult weight change|| | ||||||||||

| Lost weight | 139/2,031 | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 75/1,048 | 1.19 (0.89–1.60) | 64/983 | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) | ||||

| 0–<6 kg | 393/6,593 | 1.00 (ref) | 169/3,221 | 1.00 (ref) | 224/3,372 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 6–<10 kg | 327/5,464 | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 151/2,645 | 1.09 (0.86–1.37) | 176/2,820 | 0.94 (0.76–1.16) | ||||

| 10–<20 kg | 561/9,697 | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) | 222/4,766 | 0.86 (0.69–1.06) | 339/4,931 | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | ||||

| ≥20 kg | 584/9,090 | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 0.004 | 267/4,254 | 1.15 (0.93–1.41) | 317/4,836 | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) | |||

| Per 5 kg | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.02 | 0.72 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.5 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.06 | |||

| Colorectal cancer specific mortality | ||||||||||

| BMI Recent | ||||||||||

| <18.5 | 15/388 | 0.90 (0.51–1.58) | 12/313 | 1.04 (0.54–2.02) | -- | -- | ||||

| 18.5–<25 | 383/10,540 | 1.00 (ref) | 217/6,601 | 1.00 (ref) | 166/3,939 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 25–<30 | 481/11,703 | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | 172/4,386 | 1.25 (1.01–1.55) | 309/7,317 | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | ||||

| ≥30 | 354/7,674 | 1.19 (1.03–1.39) | 0.41 | 158/3,422 | 1.28 (1.03–1.60) | 196/4,251 | 1.09 (0.87–1.35) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 30–<35 | 215/5,062 | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 82/1,939 | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) | 133/3,123 | 1.02 (0.81–1.30) | ||||

| 35–<40 | 90/1,636 | 1.36 (1.07–1.72) | 41/892 | 1.20 (0.85–1.72) | 49/744 | 1.53 (1.08–2.15) | ||||

| ≥40 | 49/975 | 1.24 (0.91–1.69) | 0.15 | 35/591 | 1.45 (0.98–2.15) | 14/384 | 0.79 (0.45–1.39) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Per 5 kg/m2§ | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.006 | 0.23 | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 0.01 | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 0.3 | |||

| BMI at age 20 y | ||||||||||

| <18.5 | 70/2,054 | 0.94 (0.73–1.22) | 53/1,525 | 0.94 (0.69–1.27) | 17/530 | 0.95 (0.57–1.58) | ||||

| 18.5–<25 | 820/21,564 | 1.00 (ref) | 411/11,319 | 1.00 (ref) | 409/10,245 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 25–<30 | 238/5,064 | 1.10 (0.95–1.29) | 52/1,215 | 1.05 (0.78–1.43) | 186/3,849 | 1.09 (0.91–1.31) | ||||

| ≥30 | 70/1,098 | 1.44 (1.11–1.85) | 0.18 | 31/379 | 1.76 (1.18–2.62) | 39/719 | 1.20 (0.84–1.70) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 30–<35 | 53/853 | 1.55 (1.16–2.07) | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| ≥35 | 17/245 | 1.15 (0.70–1.90) | 0.30 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Per 5 kg/m2§ | 1.08 (1.00–1.16) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.004 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.99 | |||

| Adult weight change|| | ||||||||||

| Lost weight | 72/1,831 | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 39/991 | 1.10 (0.74–1.63) | 33/840 | 0.83 (0.54–1.27) | ||||

| 0–<6 kg | 244/6,035 | 1.00 (ref) | 109/2,946 | 1.00 (ref) | 135/3,088 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||

| 6–<10 kg | 201/5,096 | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) | 92/2,478 | 1.08 (0.81–1.45) | 109/2,618 | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | ||||

| 10–<20 kg | 357/8,873 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 144/4,344 | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | 213/4,529 | 1.11 (0.88–1.40) | ||||

| ≥20 kg | 334/8,202 | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 0.19 | 167/3,858 | 1.16 (0.89–1.50) | 167/4,344 | 0.94 (0.73–1.20) | |||

| Per 5 kg | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.09 | 0.23 | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.1 | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.5 | |||

Adjusted for sex, TNM stage, cigarette smoking, Colon-CFR study site, and age at diagnosis (strata statement).

Wald P-value for linear trend, excluding underweight BMI.

Calculated from −2 log likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without interaction terms between BMI (or weight change) and sex.

Underweight BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) not included in model.

Adjusted for factors listed in * and additionally adjusted for BMI at age 20.

The joint impact of pre-diagnosis recent BMI and MSI status is shown in Table 3. Compared to persons with MS-stable/MSI-low and normal BMI, risk of death was higher for MS-stable/MSI-low and obesity (HR: 1.32), not statistically-significantly lower for MSI-high and normal BMI (HR: 0.86), and essentially the same for MSI-high and obesity (HR: 1.00).

Table 3.

Joint associations of body mass index and microsatellite instability status on all-cause mortality: the Colon Cancer Family Registry, 1997 to 2012.

| MS-stable and MSI-low

|

MSI-high

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths/Person years | Multivariable HR (95% CI)* | Deaths/Person years | Multivariable HR (95% CI)* | |

| Recent BMI | ||||

| 18.5–<25 | 425/7,530 | 1.00 (ref) | 60/1,556 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) |

| 25–<30 | 532/8,419 | 1.19 (1.04–1.36) | 44/1,547 | 0.58 (0.42–0.80) |

| ≥30 | 376/5,481 | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 47/1,062 | 1.00 (0.74–1.37) |

Adjusted for sex, TNM stage, cigarette smoking, Colon-CFR study site, and age at diagnosis (strata statement).

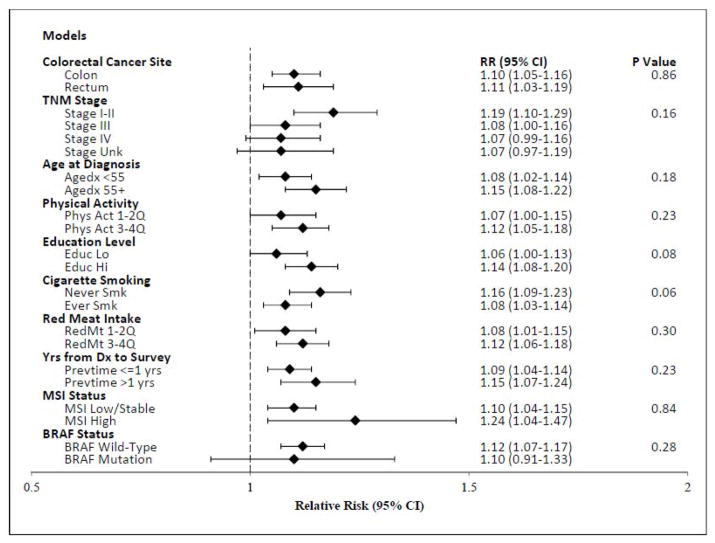

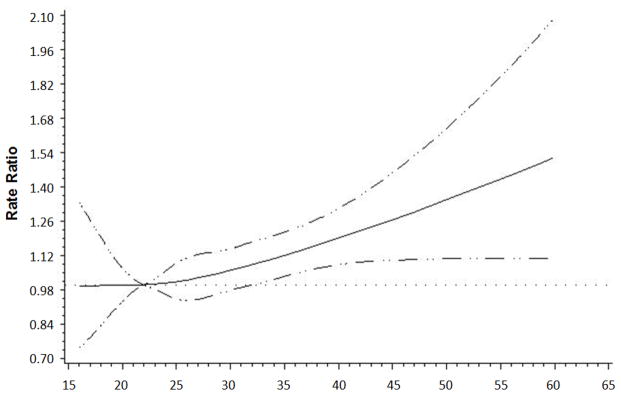

As shown in Figure 2, there was no compelling evidence that the association between recent BMI per 5 kg/m2 and all-cause mortality differed by site in the colon or rectum, stage, age at diagnosis, physical activity, red meat intake, or time from diagnosis to enrollment. Pre-diagnosis recent BMI was associated with higher risks of all-cause mortality among persons with both MS-stable/MSI-low (HR: 1.10) and MSI-high (HR: 1.24) tumors (P-interaction: 0.84). Similarly, BMI was associated with all-cause mortality for both strata of BRAF-mutation status (P-interaction: 0.28), although the CIs for the smaller BRAF-mutation group overlapped 1 (HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.91 to 1.33). There was some suggestion that risk of mortality with BMI might be higher for never smokers than ever smokers, although not statistically significant (P-interaction: 0.06). From Figure 3, the relationship between pre-diagnosis recent BMI and all-cause mortality appears linear (p-linearity: <0.0001). In sensitivity analyses that excluded all persons with any missing stage data, the study results were essentially unchanged (data not shown), as expected since stage was not a confounder or effect modifier in this study.

Figure 2.

Relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs for deaths from all causes per 5 kg/m2 of BMI for persons diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the Colon Cancer Family Registry, 1997 to 2012.

P-values for heterogeneity are calculated by comparing the likelihood ratio statistic from models with and without interaction terms. Models are adjusted for sex, TNM stage, cigarette smoking, Colon-CFR study site, and age at diagnosis (strata statement).

Figure 3.

Restricted cubic spline analysis of recent pre-diagnosis BMI and all-cause mortality for men and women diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the Colon-Cancer Family Registry, 1997 to 2012.

Solid line indicates hazard ratio while dashed line indicates 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort of 5,615 persons with invasive colon or rectal cancer, high BMI was associated with higher risks of all-cause and colorectal cancer-specific mortality in a dose-response and linear manner. Mortality estimates for pre-diagnosis recent BMI were consistent in magnitude across strata of sex, MSI, BRAF, stage, and other factors, suggesting that pre-diagnostic BMI is a robust indicator for colorectal cancer survival. These results also suggest that self-reported adult weight gain is not strongly associated with mortality risk for most colorectal cancer survivors.

The association between excess adiposity and colorectal cancer survival has been inconsistent despite several expert and consensus reports recommending that cancer survivors maintain or achieve a normal weight BMI (41, 42). Part of this inconsistency stems from differences in study methodology, predominantly the timing of BMI measurement relative to diagnosis (14). Studies that evaluated BMI after diagnosis in prospective cohorts (12, 13) or at around the time of diagnosis in adjuvant-treatment trials (16–18, 20) showed no evidence of association or only modestly higher risks of mortality with high BMI. In most previous studies where BMI was reported a year or more prior to colorectal cancer diagnosis, high BMI was associated with higher mortality (12, 13, 15, 24, 25). The magnitude of this association is similar across studies, including in this study, with HRs in the range of 1.2 to 1.5 for the association between obese BMI and all-cause mortality.

Several biological mechanisms may explain the poorer prognosis from high BMI; some factors may also relate to colorectal cancer risk, including insulin and its associated growth factors and binding proteins, inflammation, oxidative stress and impaired immune surveillance. Other, less explored, mechanisms include the potential for obesity to lead to the diagnosis of more biologically aggressive tumors, independent of stage and grade (29). To this end, higher BMI was associated with higher risk of the more-aggressive MS-stable tumors, but not associated with risk of the less-aggressive MSI-high tumors, in a previous study from the Colon-CFR (8), suggesting that BMI may not be as relevant in the context of developing an MSI-high tumor. In this analysis, we extend those findings to show BMI is relevant to colorectal cancer survival for patients with both MS-stable and MSI-high tumors, although the MSI-high group compared to the MS-stable group still maintains a prognostic advantage at each level of BMI. The role of BMI with colorectal cancer risk and survival according to various molecular markers has been examined in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Using this extensive molecular pathologic epidemiology (MPE) resource, BMI was differentially associated with risks of colorectal cancer according to CTNNB1 (43) and FASN (11) expression status. Further work from this MPE resource showed that BMI differentially influences survival for colorectal cancer patients when groups are stratified by expression patterns of TP53 (44), CTNNB1 (45), p21 (46), STMN-1 (47), p27 (48), and FASN (49). Given the complex nature of colorectal cancer and the myriad of potential interactions that may occur between adiposity-markers and the tumor microenvironment, further work is clearly needed to better understand the biologic role of obesity on colorectal cancer risk and prognosis.

Clinical factors generally do not seem to explain the association between high BMI and poorer prognosis: compared to participants with a normal BMI enrolled on a clinical trial for colon cancer adjuvant treatment, obese participants had lower rates of leukopenia, nausea and grade 3 or 4 toxicity and no differences were noted for emesis, diarrhea, stomatitis, and treatment related death (16). Similarly, in a study of rectal cancer patients, BMI did not modify rates of nausea, emesis or diarrhea; however, obese persons were less likely to experience leukopenia, neutropenia, stomatitis, and any grade 3 or 4 toxicity (17).

One limitation of this study is that post-diagnosis body weight and potential confounders (e.g., physical activity and diet) were not comprehensively available. Body weight can change after diagnosis, due to the disease itself or as an effect of treatment. In the largest of the studies that had both pre- and post-diagnosis BMI for colorectal cancer survivors, pre-diagnosis BMI, but not post-diagnosis BMI, was associated with higher risk of mortality (12). This attenuation of association probably reflects illness-associated weight loss in the post-diagnosis setting (12, 50). With the evidence accumulated thus far, and given the established relationship between BMI and several causes of death beyond colorectal cancer, it seems reasonable to conclude that pre-diagnosis BMI is associated with higher risk of death among colorectal cancer survivors. Further, because the post-diagnosis BMI analyses are likely confounded by illness, studies are needed that can distinguish between weight loss from illness/cachexia versus lifestyle modification (e.g., physical activity and/or caloric restriction) to clarify the prognostic role of weight-loss interventions for overweight/obese colorectal cancer survivors. Importantly, several observational studies have suggested that higher post-diagnosis physical activity among colorectal cancer survivors is associated with improved prognosis independent of BMI (13, 51, 52).

This study lacked detailed data on treatment, toxicity, surgical complications, and cancer recurrence; however, a recent pooled study of over 25,000 colon cancer patients enrolled on adjuvant treatment trials showed that adjuvant treatment did not confound or modify the association between BMI and all-cause mortality (20). Dose capping for adjuvant therapy among obese colorectal cancer patients was demonstrated to have no material influence on a variety of outcomes, including colon cancer recurrence and all-cause mortality (18). Another limitation of this study was that participants were asked to recall their body weight before cancer diagnosis. Cross-sectional data show that self-reported BMI values are typically slightly lower than directly measured values (53); under-reporting of self-reported BMI may overestimate associations of overweight BMI with risk of mortality and concurrently underestimate the association for obese BMI. Good-to-excellent agreement was reported, however, in studies with similar demographic characteristics to this study for self-reported and directly measured values of height and weight (54, 55). Furthermore, prospective studies with height and weight data reported many years prior to colorectal cancer diagnosis (12, 13, 15, 24, 25) have shown similar associations to those reported in this study, providing some re-assurance that recall bias is less likely to be a major concern.

Distinct advantages of this study include its large sample size and the availability of data on MSI, BRAF, smoking, and other potential effect modifiers, which allowed for the examination of whether the sub-group differences often observed in incidence studies applied to prognosis. The meta-analysis by Parkin et al. (14) identified summary HRs for the association between BMI per 5 kg/m2 and all-cause mortality by sex (women, HR: 1.16; men, HR: 1.07) that were similar to our findings, suggesting that sex is not an effect modifier in prognosis studies, in contrast to results from incidence studies where associations are typically higher for men than women (2–5). Few studies have examined whether risk of mortality with BMI differed by site within the colorectum (12, 24, 25). In the current study, we observed essentially the same risk estimates for the colon and rectum. The Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort observed stronger associations between BMI and mortality for persons diagnosed with rectal than colon cancers (12), similar to the results from Haydon et al. (25). Doria-Rose et al. showed that BMI was associated with risk of mortality among women diagnosed with colon, but not rectal, cancer (24). We are not aware of a clear explanation for these discrepant findings; it is plausible that chance is playing a role. Future work, preferably with pooled data from multiple prospective studies, will be needed to clarify this issue.

In this study, there were no statistical interactions between pre-diagnostic BMI and BRAF or MSI, suggesting that high BMI is associated with worse prognosis regardless of these tumor subtypes. For patients with MSI-high tumors, this observation may be clinically relevant, particularly for stage II disease because MSI-high status is recommended to identify patients who do not need or benefit from 5-FU-based adjuvant therapy (56). Accordingly, obesity in stage II colon cancer patients has potential implications for treatment that should be considered in future studies. We report suggestive, albeit not statistically significant, evidence that smoking may modify the link between BMI and all-cause mortality. This phenomenon occurs in more general populations (57–59) and is attributed to smoking-dose being correlated with lower BMI and with higher risk of death. It is important to note that several sub-group comparisons were made in this analysis and these results may be due to chance.

In conclusion, in this cohort of colorectal cancer survivors, high pre-diagnosis BMI was associated with higher all-cause and colorectal-cancer-specific mortality; these associations were consistent across strata of sex, tumor molecular phenotype, TNM summary stage, site in the colorectum, age at diagnosis, and red meat intake. Importantly, high BMI attenuated the survival advantage otherwise observed among persons with MSI-high tumors. Further research is needed to address the biologic causes and clinical implications of this association.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This work was supported by grant UM1 CA167551 from the National Cancer Institute and through cooperative agreements with the following C-CFR centers:

Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01/U24 CA097735, to M.A. Jenkins),

USC Consortium Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01/U24 CA074799, to R.W. Haile, D.J. Ahnen and J.A. Baron),

Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (U01/U24 CA074800, to N.M. Lindor),

Ontario Registry for Studies of Familial Colorectal Cancer (U01/U24 CA074783, to S. Gallinger),

Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01/U24 CA074794, to P.A. Newcomb),

University of Hawaii Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01/U24 CA074806, to L. Le Marchand).

Additionally, National Cancer Institute grants K05CA152715 (P. A. Newcomb), K07CA172298 (A. I. Phipps), RO1CA155101 (J. Figueiredo) and 1K05CA142885 (F.A. Sinicrope) supported this work.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of tumor tissue from the Jeremy Jass Memorial Pathology Bank.

The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centers in the Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government or the CCFR.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Limburg has the following disclosures to report: Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Exact Sciences, and Everyday Health. The remaining authors report that they have no disclosures that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ning Y, Wang L, Giovannucci EL. A quantitative analysis of body mass index and colorectal cancer: findings from 56 observational studies. Obes Rev. 2010;11:19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Zhang P, Shi C, Zou Y, et al. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PloS one. 2013;8:e53916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell PT, Cotterchio M, Dicks E, Parfrey P, Gallinger S, McLaughlin JR. Excess body weight and colorectal cancer risk in Canada: associations in subgroups of clinically defined familial risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1735–44. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slattery ML, Curtin K, Anderson K, Ma KN, Ballard L, Edwards S, et al. Associations between cigarette smoking, lifestyle factors, and microsatellite instability in colon tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1831–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.22.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satia JA, Keku T, Galanko JA, Martin C, Doctolero RT, Tajima A, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and genomic instability in the North Carolina Colon Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:429–36. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell PT, Jacobs ET, Ulrich CM, Figueiredo JC, Poynter JN, McLaughlin JR, et al. Case-control study of overweight, obesity, and colorectal cancer risk, overall and by tumor microsatellite instability status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:391–400. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes LA, Williamson EJ, van Engeland M, Jenkins MA, Giles GG, Hopper JL, et al. Body size and risk for colorectal cancers showing BRAF mutations or microsatellite instability: a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1060–72. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yoon HH, Smyrk TC, Kim GP, Allegra CJ, et al. Association of obesity with DNA mismatch repair status and clinical outcome in patients with stage II or III colon carcinoma participating in NCCTG and NSABP adjuvant chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:406–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuchiba A, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Liao X, Chan AT, et al. Body mass index and risk of colorectal cancer according to fatty acid synthase expression in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:415–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell PT, Newton CC, Dehal AN, Jacobs EJ, Patel AV, Gapstur SM. Impact of body mass index on survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis: the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:42–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuiper JG, Phipps AI, Neuhouser ML, Chlebowski RT, Thomson CA, Irwin ML, et al. Recreational physical activity, body mass index, and survival in women with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1939–48. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkin E, O’Reilly DA, Sherlock DJ, Manoharan P, Renehan AG. Excess adiposity and survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:434–51. doi: 10.1111/obr.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedirko V, Romieu I, Aleksandrova K, Pischon T, Trichopoulos D, Peeters PH, et al. Pre-diagnostic anthropometry and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis in Western European populations. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1949–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, Mayer RJ, Benson AB, 3rd, Macdonald JS, et al. Influence of body mass index on outcomes and treatment-related toxicity in patients with colon carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:484–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyerhardt JA, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, McCollum AD, Brady D, et al. Impact of body mass index on outcomes and treatment-related toxicity in patients with stage II and III rectal cancer: findings from Intergroup Trial 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:648–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, Raich P, Colangelo L, O’Connell MJ, et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1647–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Sargent DJ, O’Connell MJ, Rankin C. Obesity is an independent prognostic variable in colon cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1884–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yothers G, Benson A, Seitz JF, Labianca R, et al. Body mass index at diagnosis and survival among colon cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2013;119:1528–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo YH, Lee KF, Chin CC, Huang WS, Yeh CH, Wang JY. Does body mass index impact the number of LNs harvested and influence long-term survival rate in patients with stage III colon cancer? International journal of colorectal disease. 2012;27:1625–35. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chin CC, Kuo YH, Yeh CY, Chen JS, Tang R, Changchien CR, et al. Role of body mass index in colon cancer patients in Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4191–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alipour S, Kennecke HF, Woods R, Lim HJ, Speers C, Brown CJ, et al. Body mass index and body surface area and their associations with outcomes in stage II and III colon cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44:203–10. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doria-Rose VP, Newcomb PA, Morimoto LM, Hampton JM, Trentham-Dietz A. Body mass index and the risk of death following the diagnosis of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haydon AM, Macinnis RJ, English DR, Giles GG. Effect of physical activity and body size on survival after diagnosis with colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006;55:62–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.068189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prizment AE, Flood A, Anderson KE, Folsom AR. Survival of women with colon cancer in relation to precancer anthropometric characteristics: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2229–37. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, Dogliotti E. Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2788–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, Aronson MD, Holowaty EJ, Bull SB, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:69–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogino S, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. Molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal neoplasia: an emerging transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary field. Gut. 2011;60:397–411. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Burnett-Hartman AN, Coghill AE, Passarelli MN, et al. BRAF mutation status and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to patient and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1792–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newcomb PA, Baron J, Cotterchio M, Gallinger S, Grove J, Haile R, et al. Colon Cancer Family Registry: an international resource for studies of the genetic epidemiology of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2331–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.coloncfr.org. Melbourne: Cancer Family Registries Informatics Support Center; p. c2015. homepage on the internet. [cited 5 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.coloncfr.org/questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1998. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, Goldberg RM, Cunningham JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1043–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cicek MS, Lindor NM, Gallinger S, Bapat B, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA, et al. Quality assessment and correlation of microsatellite instability and immunohistochemical markers among population- and clinic-based colorectal tumors results from the Colon Cancer Family Registry. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchanan DD, Sweet K, Drini M, Jenkins MA, Win AK, English DR, et al. Risk factors for colorectal cancer in patients with multiple serrated polyps: a cross-sectional case series from genetics clinics. PloS one. 2010;5:e11636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Joint Committee on Cancer. Manual for Staging of Cancer. 3. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walters S, Maringe C, Butler J, Brierley JD, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Comparability of stage data in cancer registries in six countries: lessons from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:676–85. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–74. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demark-Wahnefried W, Platz EA, Ligibel JA, Blair CK, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, et al. The role of obesity in cancer survival and recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1244–59. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, et al. Prospective analysis of body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer risk associated with beta-catenin (CTNNB1) status. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1600–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Liao X, Imamura Y, Yamauchi M, Qian ZR, et al. Tumor TP53 expression status, body mass index and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1169–78. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Meyerhardt JA, Shima K, Nosho K, et al. Association of CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) alterations, body mass index, and physical activity with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:1685–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogino S, Nosho K, Shima K, Baba Y, Irahara N, Kirkner GJ, et al. p21 expression in colon cancer and modifying effects of patient age and body mass index on prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2513–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogino S, Nosho K, Baba Y, Kure S, Shima K, Irahara N, et al. A cohort study of STMN1 expression in colorectal cancer: body mass index and prognosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2047–56. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogino S, Shima K, Nosho K, Irahara N, Baba Y, Wolpin BM, et al. A cohort study of p27 localization in colon cancer, body mass index, and patient survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1849–58. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogino S, Nosho K, Meyerhardt JA, Kirkner GJ, Chan AT, Kawasaki T, et al. Cohort study of fatty acid synthase expression and patient survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5713–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renehan AG, Crosbie EJ, Campbell PT. Re: Prediagnosis body mass index, physical activity, and mortality in endometrial cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:876–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shields M, Gorber SC, Tremblay MS. Effects of measurement on obesity and morbidity. Health Rep. 2008;19:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAdams MA, Van Dam RM, Hu FB. Comparison of self-reported and measured BMI as correlates of disease markers in US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:188–96. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–5. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2211–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]