Summary

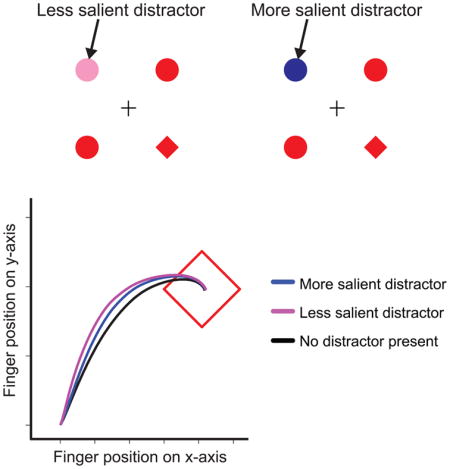

Everyday behavior frequently involves encounters with multiple objects that compete for selection. For example, driving a car requires constant shifts of attention between oncoming traffic, rearview mirrors, and traffic signs and signals, among other objects. Behavioral goals often drive this selection process [1–2]; however, they are not the sole determinant of selection. Physically salient objects, such as flashing, brightly colored hazard signs, or objects that are salient by virtue of learned associations with reward, such as pictures of food on a billboard, often capture attention regardless of the individual’s goals [3–6]. It is typically thought that strongly salient distractor objects capture more attention and are more disruptive than weakly salient distractors [7–8]. Counter-intuitively, though, we found that this is true for perception but not for goal-directed action. In a visually-guided reaching task [9–11], we required participants to reach to a shape-defined target while trying to ignore salient distractors. We observed that strongly salient distractors produced less disruption in goal-directed action than weakly salient distractors. Thus, a strongly salient distractor triggers suppression during goal-directed action, resulting in enhanced efficiency and accuracy of target selection relative to when weakly salient distractors are present. In contrast, in a task requiring no goal-directed action, we found greater attentional interference from strongly salient distractors. Thus, while highly salient stimuli interfere strongly with perceptual processing, increased physical salience or associated value attenuates action-related interference.

Keywords: salience, visually-guided action, suppression, reach movements, reward learning

Graphical abstract

Results

The functional role of salience in guiding selection is unclear. We use “salience” here to refer to objects that are distinct from their surroundings, either because of high feature contrast (physical salience) or learned associations with reward. To the extent that salient stimuli are ecologically relevant, signaling danger or opportunity, automatically attending to such stimuli may confer adaptive benefits. However, in many cases these stimuli are not meaningful to the organism and serve only to distract from the selection of goal-relevant stimuli. One possibility is that attentional capture by irrelevant but salient stimuli reflects the overgeneralization of an adaptive principle—better safe (check to see if the salient stimulus is pertinent) than sorry (ignore a salient stimulus that is pertinent and suffer the consequences).

In real-world contexts, however, people often not only have to find target objects, but also reach to those objects to manipulate them in ways that will help them achieve their goals. Thus, it is important to consider the relationship between attentional selection and action output in order to fully understand the impact of salient distractors on behavior. Here, we examine whether physical salience of distracting objects or their learned associations with reward provide an adaptive benefit when multiple objects compete not only for perceptual selection but also for goal-directed action responses.

Capture in goal-directed action

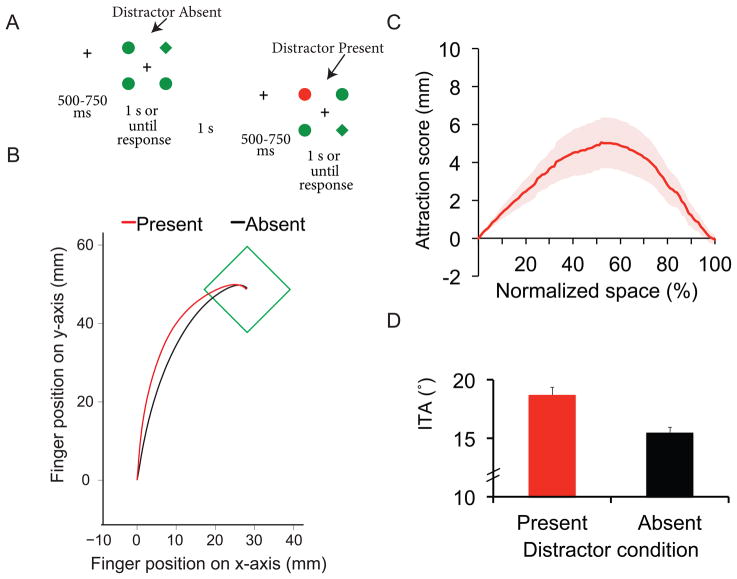

In Experiment 1, participants reached to a shape-defined singleton target, while trying to ignore physically salient color singleton distractors that appeared on a randomly selected and intermixed half of all trials (Fig. 1A). Examining distractor attraction scores [12], a measure of how far hand movements deviated towards the color singleton distractor (Fig. 1B; see supplemental methods), we found significant deviation that appeared immediately and persisted through 88% of the movement trajectory (Fig 1C; see methods for details on statistical calculation). This finding is consistent with previous reach movement studies suggesting that action is automatically directed towards physically salient objects [13–15]. The initial trajectory angle (ITA) [17] of hand movements was also greater on distractor present trials (18.7°) than absent trials (15.5°), t(15)= 5.99, p < 001 (Fig. 1D). This outcome suggests a robust pattern of interference, with deviation towards the distractor occurring immediately and continuing for most of the movement. Additional dependent measures can be found in the supplemental materials (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Stimuli and data from Experiment 1. A) A sample sequence of trials from Experiment 1. Participants were required to point to the unique shape. One of the non-unique shapes was colored red on 50% of all trials. B) Average resampled trajectory across all subjects for a target located in the lower right corner on distractor absent trials (black line), and a target located in the lower right corner with a color distractor in the upper left corner (red line). C) Distractor attraction scores calculated across the entire resampled movement, averaged across all subjects. Positive scores indicate hand position that is pulled towards the location of the color distractor on distractor present trials. D) Initial trajectory angles for distractor present and absent trials. All error bars reflect standard error of the mean (S.E.M.).

This impact of physical salience on goal-directed action is generally consistent with studies of perceptual selection (see also; Fig. S1). However, some objects “pop-out” more than others due to a higher level of contrast. Thus, in Experiment 2, we explored another important question regarding the relationship between physical salience and goal-directed action: are more strongly salient objects necessarily more disruptive?

At first glance, the answer might seem obvious - surely the more salient stimulus is more disruptive. Indeed, most models of attention consider the role of physical salience itself as a positively increasing monotonic function in which increasing the physical salience of a particular object increases the probability that the object is selected [3,7–8]. However, salience may have a different effect on selection for action than it does on selection for vision [cf. 16–17]. For example, in recent years, the role of suppression in the selection process has gained traction [18–23]. It is possible that strongly salient distractors might trigger suppression mechanisms that prevent movements from going to the wrong object, resulting in less interference from strongly salient relative to weakly salient distractors during goal-directed action.

Strong physical salience triggers rapid suppression in goal-directed action

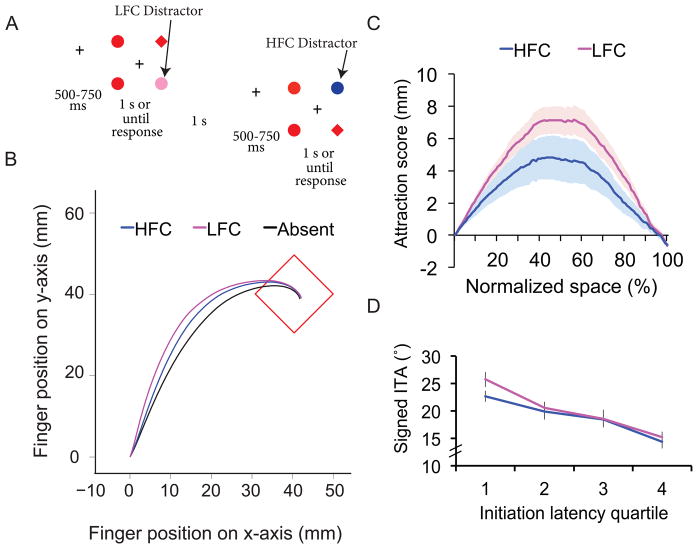

To manipulate physical salience, we varied the color of the singleton distractor in Experiment 2 (Fig. 2A); all objects appeared in red, except for color singleton distractors, which appeared either in pink (low feature contrast, LFC, weak physical salience), or an equiluminant blue (high feature contrast, HFC, strong physical salience; Fig. S2A).

Figure 2.

Stimuli and data from Experiment 2. A) A sample sequence of trials from Experiment 2. One of the non-unique shapes was colored either pink or blue, with equal probability, on 50% of all trials. B) Average resampled trajectory across all subjects for a target located in the lower right corner on distractor absent trials (black line), a target located in the lower right corner with a HFC distractor in the upper left corner (blue line), and a target located in the lower right corner with a LFC distractor in the upper left corner (pink line). C) Distractor attraction scores calculated across the entire resampled movement, averaged across all subjects. The pink line shows scores for the LFC distractor, and the blue line shows scores for the HFC distractor. Positive scores indicate hand position that is pulled towards the location of the color distractor on distractor present trials. D) Signed ITA across four quartiles of initiation latency, from shortest to fastest, for both LFC and HFC distractors. All error bars reflect S.E.M.

Surprisingly, we found that the more physically salient blue distractor caused less deviation in hand movement trajectories (Fig. 2B). Distractor attraction scores from pink LFC distractors were greater than blue HFC distractors from 10% through 78% of the movement (Fig. 2C). Signed ITA, which was positive or negative depending on whether the hand deviated towards or away from the location of the distractor, was also higher for LFC (21.0°) than HFC (19.3°) distractors, t(16) = 3.54, p < .01. This difference was not a consequence of slower initiation latency on HFC trials [24], as there was no significant effect of trial type on initiation latency, and initiation latency was numerically shorter on HFC trials than LFC trials (407 ms vs. 409 ms, n.s.).

These data point towards a novel finding: the weakly salient distractor produced greater distractor interference during goal-directed action than the strongly salient distractor (see also; Fig. S2). Given the previous literature [3, 7–8], it is unlikely that the weakly salient distractor competed more strongly for attentional selection. Instead, it appears that the salient distractor triggered a suppression mechanism, reducing distractor interference relative to the weakly salient distractor in an integrated attention-action system. This view is consistent with previous literature interpreting reduced curvature or curvature away from a location as inhibition [25–27; see also Fig. S1B for additional support for this claim, via a link between trajectory deviation and subsequent negative priming].

An alternative explanation for this result is that participants were able to more rapidly disengage attention from the HFC distractor [28] because of its high physical salience. However, Figure 2C clearly shows that the distractor attraction scores between the LFC and HFC distractors diverged well before they reached their peak, indicating that the difference emerged rapidly and is not attributable solely to more rapid disengagement from the HFC distractor. Another possibility is that the overall difference in distractor attraction scores reflects a slow-acting suppression mechanism (see Fig. S1A) in goal-directed action that is triggered only by the strongly salient distractor. However, we found that differences between HFC and LFC trials in signed ITA measures did not significantly change across initiation latency quartile, interaction: F(3,48) = 1.49, p = .23 (Fig. 2D and S2A) and are thus not attributable to a slow-acting top-down suppression mechanism [25–27, 29].

In Experiment 3, we created a perception-based version of the task to determine whether this rapid salience-triggered suppression is specific to goal-directed action. Participants indicated the orientation of a line (vertical or horizontal) inside the unique shape target while trying to ignore physically salient HFC or LFC distractors that appeared on half of all trials. A line discrimination task was used in order to roughly equate the attentional demands to the goal directed-action tasks, as both require a shift of focal attention to the target [9, 30]. Each participant also completed the reaching version of the task to provide a within-subject comparison.

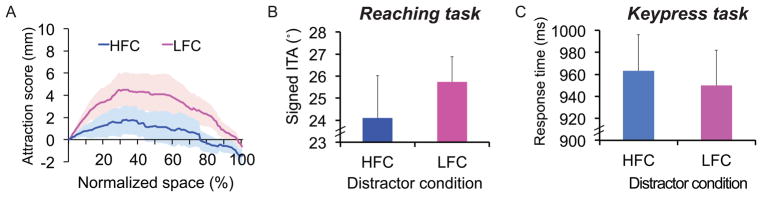

Results from the visually-guided action task of Experiment 3 largely replicated the results of Experiment 2 (see Fig. 3A, 3B, and S3). For the keypress task, response time was also affected by the presence of salient distractors; however, this effect was in the opposite direction of the reaching behavior. That is, interference was greater from the HFC than the LFC distractors, reflected in longer response times (HFC: 963 ms, LFC: 950 ms, t(11) = 2.85, p < .05; Fig. 3C; see also, Table S2). Similar results were obtained in an otherwise identical keypress experiment that required a localization judgment of the target (Experiment S1; see Supplemental Methods, Fig. S3B, Table S2), ruling out the possibility that the dissociation in the effect of salience on performance between the keypress and reaching versions of the task was due to different target localization requirements. In summary, the results demonstrate a clear dissociation in how physical salience affects performance depending on whether observers are required to make a movement towards their target.

Figure 3.

Data from Experiment 3. A) Distractor attraction scores calculated across the entire resampled movement, averaged across all subjects, for the visually-guided action task in Experiment 3. The pink line shows scores for the LFC distractor, and the blue line shows scores for the HFC distractor. Positive scores indicate hand position that is pulled towards the location of the color distractor on distractor present trials. Scores were higher for the LFC distractor from 40% through 89% of the movement, replicating Experiment 2. B) Signed ITA for HFC and LFC trials. C) Response times for the keypress task in Experiment 3 for HFC and LFC distractors. All error bars reflect S.E.M.

Previous work using the value-driven capture paradigm [5–6] has shown that when a feature becomes associated with high monetary payouts, that feature captures attention automatically even after reward is extinguished. This value-based capture may occur via a priority map, similar to the effects of physical salience [31]. Thus, to test the generalizability of salience-triggered suppression, we conducted a final set of experiments using a modified version of the value-driven capture paradigm [5–6,32–36]. If reward-driven salience also triggers suppression in goal-directed action, we might expect reduced capture for distractors previously associated with comparatively high reward in a reaching task. Because reward-associated colors are counterbalanced across participants, this approach addresses concerns about the suppression effects in Experiments 2 and 3 being driven by the physical properties of the stimuli [37].

Does salience-triggered suppression extend to value-driven capture?

In the training phase of Experiment 4, participants reached to a target circle (unpredictably red or green) on every trial (Fig. 4A). One target color was probabilistically associated with high monetary reward, the other with low reward. In a subsequent test phase, participants pointed to a singleton target shape on each trial, similar to Experiment 1. On a randomly selected 50% of all trials, either the high-value (previously associated with high reward) or low-value (previously associated with low reward) color appeared as a color singleton distractor (Fig. 4A).

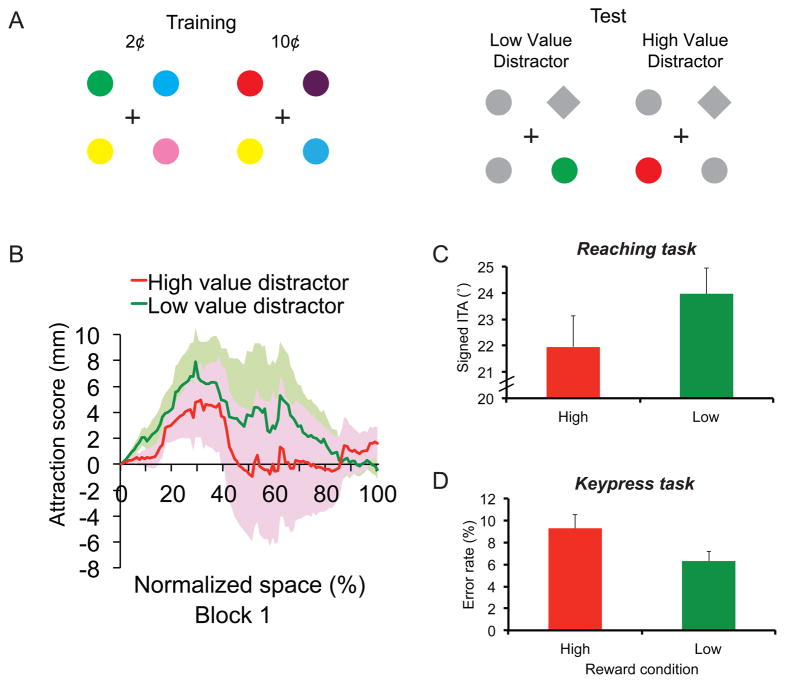

Figure 4.

Stimuli and data from Experiments 4 and 5. A) Sample displays for the training and test phases of Experiment 4. Participants were required to reach to the red or green target during the training phase, and to the unique shape during the test phase. Experiment 5 required a keypress response instead of a reach movement to indicate the orientation of a line inside the target. B) Distractor attraction scores calculated across the entire resampled movement, averaged across all subjects, for Block 1 of the test phase in Experiment 4. The red line shows scores for the high-reward associated distractor, and the green line shows scores for the low-reward associated distractor. Positive scores indicate hand position that is pulled towards the location of the color distractor on distractor present trials. C) Experiment 4 initial trajectory angles for high and low reward associated distractors. D) Experiment 5 keypress error rate for high and low reward distractors. All error bars reflect S.E.M.

For responses in the test phase, signed ITA was greater in the direction of the low-value distractor (24°) than the high-value distractor (21.9°), t(19) = 2.36, p < .05 (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that salience-triggered suppression for goal-directed action extends to the domain of learned value: high-value distractors trigger suppression, and thus produce less interference than low-value distractors. While overall distractor attraction scores did not differ between the two conditions, scores calculated for the first block of trials, where reward history effects are usually strongest [5], show greater deviation in the direction of the low-value distractor from 7% to 8% of the movement (Fig. 4B; see Fig. S4 for a more detailed breakdown of all results by block). Although only this small window reached statistical significance, attraction scores were greater for the low-value distractor from 2% through 86% of the movement; the lack of statistical significance over a greater area is likely due to the lack of power from restricting analysis to a small subset of trials per subject, or because of the possibility that the method for calculating distractor attraction scores may spread out an effect that occurs over a smaller time window. There was no difference in initiation latency (high-value: 438 ms, low-value: 441 ms, t[19] = 1.07, n.s.) between the two conditions.

In Experiment 5, we conducted a keypress version of the same task to replicate previous work showing greater attentional capture from comparatively high-value distractors [5,32]. Participants had to indicate the orientation of a line inside the target stimulus (horizontal or vertical) during both phases. We found the error rate was higher for high- (9.3%) than for low-value (6.1%) distractors, t(13) = 2.25, p < .05 (Fig. 4D). Thus, a perceptually salient distractor produced greater interference when it appeared in a color associated with high reward value rather than low reward value, consistent with previous psychophysical research [5,33]. Although RT was also greater in magnitude for high-value distractors (938 vs. 933 ms), this result did not reach significance, t(13) < 1. Critically, the direction of significant reward effects in the keypress task was consistent with previous literature [5,32–36], and in the opposite direction of reward effects found in the visually-guided reaching task in Experiment 4.

Together, these results again show a dissociation between selection for vision and selection for action. High-value distractors produce more errors than low-value distractors in a keypress task, but less interference in reaching movement trajectories in a visually-guided reaching task. Thus, distractors may trigger suppression in goal-directed action when they are associated with high monetary reward.

Discussion

It is typically assumed that increasing an object’s salience will increase the strength of competition from that object for selection. Surprisingly, however, we found that objects exhibiting high feature contrast, or objects previously associated with high reward, produced less interference than objects exhibiting relatively low feature contrast or previously associated with low reward during goal-directed action. This result supports the existence of a salience-triggered suppression mechanism for goal-directed action, in which strongly salient distractors rapidly trigger suppression and therefore produce less interference than would be otherwise expected during selection for action. This pattern was not observed in a perception-based visual search task. Instead, there was greater interference from the strongly salient distractor, consistent with models of attention [8,38]. Thus, salience-triggered suppression occurred only when goal-directed actions towards specific objects are required.

We aimed to match the goal-directed action and keypress tasks for attentional demands as closely as possible [9,30]. We also conducted an additional experiment that ruled out the possibility that divergent results between the two tasks were due to differences in target localization demands. Further research will be needed to more fully characterize the nature of the observed dissociation by exploring a range of task and attentional demands. For example, one possibility is that differences in the timing of response execution between the two tasks contributed to the divergent results. Nevertheless, the present results provide clear evidence of reduced interference from highly salient distractors during goal-directed action, which are at odds with prevailing views of the impact of salience on performance [7–8] and add to a growing number of studies highlighting dissociations in selection for vision and selection for action [13,16–17].

Research in both perceptual and motor domains [39–41], as well as formal models [42], have explored the notion that distractors competing strongly for target selection receive greater inhibition than distractors that compete weakly. However, inhibition in these empirical data and models typically follows an initial period of strong interference from those salient distractors, or at least does not show improved behavioral performance when distractors are more salient [39–44]. The present study demonstrates a form of inhibition that appears to directly improve task performance, by reducing motor interference from salient distractors, with no discernible initial cost. Thus, the present study adds to the literature highlighting increased inhibition of strongly salient objects, but also suggests there may be cases where strong inhibition of salient distractors can be implemented more rapidly than previously thought. Furthermore, our findings might indicate a broad principle of inhibitory control – for example, salience-triggered suppression may suggest a possible mechanism by which supra-threshold stimuli can lead to less robust perceptual learning than sub-threshold stimuli [45].

Our findings have implications for understanding the nature of distraction, both for models of integrated attention-action systems, as well as human factors and human-computer interactions considerations. Specifically, when salient distractors compete for selection for action, increasing the physical salience of those distractors may make them easier to suppress and thus facilitate goal-directed action.

Experimental Procedures

Recording and data analysis methods were largely adapted from Ref. 11. More detailed methods are available in the supplemental materials.

Experiment 1

On each trial, following fixation, four colored shapes appeared on a black background (Fig. 1A). Participants were instructed to reach to the unique shape (either a diamond among circles or a circle among diamonds) within 1 s. On a randomly selected 50% of all trials, one non-target shape was colored red. All other objects were colored green.

Three-dimensional hand position was recorded at a rate of approximately 240 Hz in Experiment 1 and 160 Hz in Experiments 2, 3, and 4 (due to a slight change in recording protocol) using an electromagnetic position and orientation recording system (Liberty, Polhemus) with a measuring error of .03 cm root mean square. Stimulus presentation was conducted using custom software designed with MATLAB (Mathworks) and Psychtoolbox [46].

Initiation latency was defined as the time elapsed between stimulus onset and movement onset. Movement time was defined as the time elapsed between movement onset and movement offset. Distractor attraction scores [12] were calculated after resampling each movement to 101 samples equally separated in space, as the difference in deviation on distractor present trials compared to distractor absent trials at each sample, signed to reflect whether the angle of trajectory in the direction of the distractor at each point was greater on distractor present or distractor absent trials (see supplemental methods for more details). Initial trajectory angle (ITA) was defined as the angle between a line connecting the start and end of the movement to a line connecting the start and the position of the hand at 20% of the movement time [16]. Signed ITA was indicated as positive if the point 20% through the movement was closer to the distractor than a line connecting the start and end of the movement, and negative if it was farther from the distractor. This measure cannot be calculated for distractor absent trials since there is no specific distractor location, so we used this only for comparing between two different types of distractors in Experiments 2–5.

The experiment began with 20 practice trials, followed by 8 blocks of 100 trials each. Participants were given an opportunity to rest between each block. Each session lasted approximately one hour.

Experiment 2

The procedure was similar to Experiment 1, except all non-distractor items were red (hue: 14°, saturation: 95%), and there were two possible singleton distractor colors: high feature-contrast (HFC) distractors (blue, .539 away from red in CIE color space, hue: 240°, saturation: 100%;) and low feature-contrast (LFC) distractors (pink, .229 away from red, hue: 322°, saturation: 90%; Fig. 1B). To further ensure that the HFC distractor exhibited greater physical salience, we calculated saliency maps from screenshots of displays from Experiment 2 (1280 × 1024 pixels; see Fig. S2B).

Experiment 3

One experimental phase was identical to Experiment 2, except that only 400 total trials were conducted after training. The other phase required keypress responses rather than reaching responses. The task for this phase was similar to Experiment 2, except that participants were instructed to respond by pressing a key to indicate whether the line inside the target shape was oriented horizontally or vertically. The response deadline for this task was 1.5 seconds, to encourage rapid responses as in the reaching task. The order of these two phases was equally counterbalanced across subjects.

Experiments 4 and 5

The protocol was similar to Ref. 5. In phase one, participants pointed to a red or green target among four differently colored circle objects. Correct answers were rewarded with 2¢ or 10¢ bonuses. One color was probabilistically (80%) associated with the high reward, while the other color was associated with the low reward. After each trial, participants saw a display indicating the reward earned for that trial and the total reward earned thus far. Phase two was similar to Experiment 1, but non-distractors were gray and color distractors were either red or green. Reward was not given out during phase 2. At the end of the study, participants received a payout equal to the reward earned in phase 1 rounded up to the nearest dollar.

For the keypress version of the task (Experiment 5), a separate group of participants did the same task, but with a keypress response to indicate the orientation of a line inside the target rather than a reach movement.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Highly physically salient distractors trigger suppression in goal-directed action

Suppression is rapidly initiated and does not require learning

No salience-triggered suppression in a perception-based psychophysical task

Reward-associated distractors also trigger suppression in goal-directed action

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by Brown University Salomon faculty research award and NIGMS-NIH (P20GM103645) to J.H.S. J.M. is supported by the Center for Vision Research fellowship and the Brown Training Program in Systems and Behavioral Neuroscience NIH T32MH019118. B.A.A. is supported by NIH NRSA F31-DA033754. We thank Hee Yeon Im, Filipe Deavila Belbute Peres, Jiyoon Stephanie Song, and Chloe Kliman-Silver for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.M., B.A.A., & J.H.S; Methodology, J.M., B.A.A., & J.H.S.; Software, J.M.; Formal Analysis, J.M.; Investigation, J.M., Writing – Original Draft, J.M.; Writing – Reviewing & Editing, J.M., B.A.A., & J.H.S; Supervision, J.H.S.; Funding acquisition, J.M., B.A.A., & J.H.S.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Green BF, Anderson LK. Color coding in a visual search task. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1956;51(1):19–24. doi: 10.1037/h0047484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posner M. Orienting of attention. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980;32(1):3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theeuwes J. Perceptual selectivity for color and form. Perception & Psychophysics. 1992;51(6):599–606. doi: 10.3758/bf03211656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theeuwes J, De Vries GJ, Godijn R. Attentional and oculomotor capture with static singletons. Perception and Psychophysics. 2003;65(5):735–746. doi: 10.3758/bf03194810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson BA, Laurent PA, Yantis S. Learned Value Magnifies Salience-Based Attentional Capture. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson BA, Laurent PA, Yantis S. Value-Driven Attentional Capture. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2011;108:10367–10371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104047108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theeuwes J. Top–down and bottom–up control of visual selection. Acta Psychologica. 2010;135(2):77–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itti L, Koch C. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(3):194–203. doi: 10.1038/35058500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JH, Nakayama K. Role of focal attention on latencies and trajectories of visually guided manual pointing. Journal of Vision. 2006;6(9):1–11. doi: 10.1167/6.9.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song JH, Nakayama K. Hidden cognitive states revealed in choice reaching tasks. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(8):360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher J, Song JH. Context-dependent sequential effects of target selection for action. Journal of Vision. 2013;13(8):1–10. doi: 10.1167/13.8.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher J, Sit J, Song J-H. Goal-directed action is automatically biased towards looming motion. Vision Research. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2014.08.005. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerzel D, Schönhammer J. Salient stimuli capture attention and action. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics. 2013 doi: 10.3758/s13414-013-0512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welsh TN. The relationship between attentional capture and deviations in movement trajectories in a selective reaching task. Acta Psychologica. 2011;137(3):300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood DK, Gallivan JP, Chapman CS, Milne JL, Culham JC, Goodale MA. Visual salience dominates early visuomotor competition in reaching behavior. Journal of Vision. 2011;11(10):1–11. doi: 10.1167/11.10.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buetti S, Kerzel D. Conflicts during response selection affect response programming: Reactions toward the source of stimulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception and Performance. 2009;35(3):816–834. doi: 10.1037/a0011092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh TN, Pratt J. Actions modulate attentional capture. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61(7):968–976. doi: 10.1080/17470210801943960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumada T, Humphreys G. Cross-dimensional interference and cross-trial inhibition. Perception & Psychophysics. 2002;64(3):493–503. doi: 10.3758/bf03194720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lleras A, Kawahara JI, Wan XI, Ariga A. Intertrial inhibition of focused attention in pop-out search. Perception & Psychophysics. 2008;70(1):114–131. doi: 10.3758/pp.70.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Trujillo JC, Treue S. Feature-based attention increases the selectivity of population responses in primate visual cortex. Current Biology. 2004;14(9):744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher J, Abrams J, Egeth HE, Yantis S, Stuphorn V. Trial-by-trial adjustments of top-down set modulate oculomotor capture. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2011;18(5):897–903. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher J, Lakshmanan BM, Egeth HE, Ewen JB. Inhibition drives early feature-based attention. Psychological Science. 2014;25(2):315–324. doi: 10.1177/0956797613511257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tipper SP, Cranston M. Selective attention and priming: inhibitory and facilitatory effects of ignored primes. The Quarterly journal of experimental psychology A, Human experimental psychology. 1985;37(4):591–611. doi: 10.1080/14640748508400921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song JH, Nakayama K. Target selection in visual search as revealed by movement trajectories. Vision Research. 2008;48(7):853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neyedli HF, Welsh TN. The processes of facilitation and inhibition in a cue–target paradigm: Insight from movement trajectory deviations. Acta Psychologica. 2012;139(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsh TN, Elliott D. Movement trajectories in the presence of a distracting stimulus: Evidence for a response activation model of selective reaching. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 2004;57(6):1031–1057. doi: 10.1080/02724980343000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard LA, Tipper SP. Hand deviations away from visual cues: indirect evidence for inhibition. Experimental Brain Research. 1997;113:144–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02454150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belopolsky A, Schreij D, Theeuwes J. What is top-down about contingent capture? Attention, Perception & Psychophysics. 2010;72(2):326–341. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tipper SP, Meegan D, Howard LA. Action-centred negative priming: Evidence for reactive inhibition. Visual Cognition. 2002;9(4–5):591–614. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher J, Song JH. Target selection bias transfers across different response actions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2014;40(3):1117–1130. doi: 10.1037/a0035739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awh E, Belopolsky AV, Theeuwes J. Top-down versus bottom-up attentional control: a failed theoretical dichotomy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(8):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson BA. A value-driven mechanism of attentional selection. Journal of Vision. 2013;13(3):1–16. doi: 10.1167/13.3.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wentura D, Muller P, Rothermund K. Attentional capture by evaluative stimuli: gain- and loss-connoting colors boost the additional singleton effect. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2014;21:701–707. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0531-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theeuwes J, Belopolsky AV. Reward grabs the eye: oculomotor capture by rewarding stimuli. Vision Research. 2012;74:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson BA, Yantis S. Value-driven attentional and oculomotor capture during goal-directed, unconstrained viewing. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics. 2012;74:1644–1653. doi: 10.3758/s13414-012-0348-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurent PA, Hall MG, Anderson BA, Yantis S. Valuable orientations capture attention. Visual Cognition. 2015;23:133–146. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2014.965242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsey DT, Brown AM, Reijnen E, Rich AN, Kuzmova YI, Wolfe JM. Color channels, not color appearance or color categories, guide visual search for desaturated color targets. Psychological Science. 2010;21(9):1208–1214. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfe J. Guided search 2.0: A revised model of visual search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1994;1(2):202–238. doi: 10.3758/BF03200774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehler CN, Tsotsos JK, Schoenfeld MA, Heinze HJ, Hopf JM. The Center-Surround Profile of the Focus of Attention Arises from Recurrent Processing in Visual Cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(4):982–991. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cave KR, Zimmerman JM. Flexibility in spatial attention before and after practice. Psychological Science. 1997;8(5):399–403. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mounts JRW. Attentional capture by abrupt onsets and feature singletons produces inhibitory surrounds. Perception and Psychophysics. 2000;62(7):1485–1493. doi: 10.3758/bf03212148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houghton G, Tipper SP, Weaver B, Shore DI. Inhibition and interference in selective attention: Some tests of a neural network model. Visual Cognition. 1996;3(2):119–164. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tipper SP, Howard LA, Jackson SR. Selective reaching to grasp: Evidence for distractor interference effects. Visual Cognition. 1997;4(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tipper SP, Meegan D, Howard LA. Action-centred negative priming: Evidence for reactive inhibition. Visual Cognition. 2002;9(4–5):591–614. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsushima Y, Seitz AR, Watanabe T. Task-irrelevant learning occurs only when the irrelevant feature is weak. Current Biology. 2008;18(12):R516–R517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brainard D. The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10(4):433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.