Abstract

Background and objectives

Little is known about patients receiving dialysis who respond to satisfaction and experience of care surveys and those who do not respond, nor is much known about the corollaries of satisfaction. This study examined factors predicting response to Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (DCI)’s patient satisfaction survey and factors associated with higher satisfaction among responders.

Design, setting, participants, & measurement

A total of 10,628 patients receiving in-center hemodialysis care at 201 DCI facilities between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2011, aged ≥18 years, treated during the survey administration window, and at the facility for ≥3 months before survey administration. Primary outcome was response to at least one of the nine survey questions; secondary outcome was overall satisfaction with care.

Results

Response rate was 77.3%. In adjusted logistic regression (odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals), race other than black (white race, 1.23 [1.10 to 1.37]), missed treatments (1.16 [1.02 to 1.32]) or shortened treatments (≥5 treatments, 1.40 [1.22 to 1.60]), more hospital days (>3 days in the last 3 months, 1.89 [1.66 to 2.15]), and lower serum albumin (albumin level <3.5 g/dl, 1.4 [1.28 to 1.73]) all independently predicted nonresponse. In adjusted linear regression, the following were more satisfied with care: older patients (age ≥63 years, 1.84 [1.78 to 1.90]; age <63 years, 1.91 [1.86 to 1.97]; P<0.001), white patients (1.76 [1.71 to 1.81]) versus black patients (1.93 [1.88 to 1.99]) or those of other race (1.93 [1.83 to 2.03]) (P<0.001), patients with shorter duration of dialysis (≤2.5 years, 1.79 [1.73 to 1.84]; >2.5 years, 1.96 [1.91 to 2.02]; P<0.001), patients who had missed one or fewer treatments (1.83 [1.78 to 1.88]) versus those who had missed more than one treatment (1.92 [1.85 to 1.98]; P=0.002) and those who had shortened treatment (for one treatment or less, 1.84 [1.77 to 1.90]; for two to four treatments, 1.87 [1.81 to 1.93]; for five or more treatments, 1.92 [1.87 to 1.98]; P=0.004).

Conclusions

Survey results represent healthier and more adherent patients on hemodialysis. Shorter survey administration windows were associated with higher response rates. Older, white patients with shorter dialysis vintage were more satisfied.

Keywords: chronic hemodialysis, epidemiology and outcomes, clinical epidemiology

Introduction

In the 1990s, the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set standards required provider organizations to survey patient satisfaction with care. Scholars have distinguished between responses regarding amenities and those about presumably more fundamental aspects of care, such as interpersonal care, communication, and coordination, thought ultimately to matter more to patients than the elegance of medical facilities (1). There was little standardization and only sparse publication, perhaps because the resulting data were considered not very interesting or because of competitive concerns.

A second distinction between satisfaction with and experience of care has subsequently emerged. Satisfaction surveys, according to this distinction, ask patients to report subjective reactions to physical, interpersonal, and organizational aspects of care, such as agreement with the statement “The staff try hard to start my treatment on time.” In contrast, surveys of experience of care do not ask how the patient feels about the care but rather ask the patient to report on the care itself (1). For example, they may ask a patient to estimate the frequency with which “the staff starts my treatment within 15 minutes of my scheduled appointment time.” In requiring Medicare providers to use the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems questionnaires, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have effectively standardized the measurement of patient experience and have steered providers to assess themselves and to respond with respect to experience of care, rather than satisfaction with it. The 2013 ESRD Quality Incentive Program required dialysis providers to administer the 58-item In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assesment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (ICH CAHPS) survey, developed in 2004 and first widely used in 2012. The 2014 ICH CAHPS results will be publically reported; dialysis facility reimbursement for 2016 will be influenced by scores from 2015 and 2016.

Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (DCI; www.dciinc.org), has measured patient satisfaction since 1995, using an internally developed nine-item instrument modeled after Eugene Nelson’s Patient Comment Card (2). As we begin to measure experience of care, it is worth understanding what we have learned from measuring satisfaction. We compare the characteristics of responders and nonresponders and summarize the corollaries of differences in satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We studied a retrospective cohort of patients undergoing long-term in-center hemodialysis at DCI facilities between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2011. The patients were age ≥18 years, present in the facility for at least 3 months before the next scheduled satisfaction survey, and received a hemodialysis treatment during the survey administration window.

Patient Satisfaction Assessment

The DCI Clinic Report Card was administered to all DCI patients annually. Facility staff distributed the survey, explained its importance, and encouraged patients to complete it, preferably in the facility or at home. No incentives were offered for survey completion. Staff were prohibited from assisting in survey completion. We advised facilities to limit survey administration to a 2- to 4-week time period and asked dialysis facility staff to explain survey nonresponse using a controlled vocabulary.

The survey uses a five-level Likert scale with responses ranging from "excellent" to "poor" to assess professionalism, teamwork, involvement with care, respect, comfort, and overall satisfaction. Patients seal completed surveys in an envelope provided by facility staff, who mail them to the Outcomes Monitoring Program for data entry. Surveys are confidential but not anonymous. The institutional review board at Tufts Medical Center and the DCI Administrative Review Office approved these analyses.

Study Data

Outcomes.

The primary study outcome was survey response. Responders were defined as patients completing at least one of the nine items. Nonresponders include patients who decline to complete the survey; do not read or speak English, Spanish, Chinese, or Vietnamese; have cognitive impairment or dementia; or have undergone transplantation or died. Also included in the nonresponder group were patients for whom the reason for nonresponse was unknown. The secondary study outcome was overall satisfaction with care.

Administration Times.

The survey administration window was defined as extending from the first to the last surveys administered at the facility. We assigned survey nonresponders a date midway between the patient’s first and last hemodialysis treatments at the facility during the survey administration window.

Independent Variables.

We examined patient characteristics (sex, race, diabetes, age, years at DCI, and years with ESRD) at survey administration and averaged clinical measures over 3 months before survey administration. Clinical variables include average serum albumin, hemoglobin, and phosphorous concentrations, dialysis dose (spKt/V), number of missed but not rescheduled treatments, treatments shortened by >10 minutes, number and length of hospitalizations, and Short Form (SF)-36 Health Survey Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores. The omission of a data point did not exclude the patient or the calculated average for the 3-month period. Survival was assessed through June 2012.

Statistical Analyses

With SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), we used the chi-squared test to assess differences between groups; Kaplan–Meier plots to assess unadjusted survival time after the survey administration window; the log-rank test for differences between groups; Spearman correlation coefficients for association between clinic characteristics and response rates; logistic regression to assess factors associated with survey nonresponse; and a mixed model to assess factors associated with the level of satisfaction. Descriptive analyses of responders and nonresponders include all patients who met the inclusion criteria. A random intercept logistic regression model implemented in Proc glimmix adjusted for clustering within center. We restricted inferential comparisons to responders and the subset of nonresponders who could have chosen to respond to the survey. In other words, we excluded those with cognitive, emotional, or language barriers.

Results

Patient Characteristics

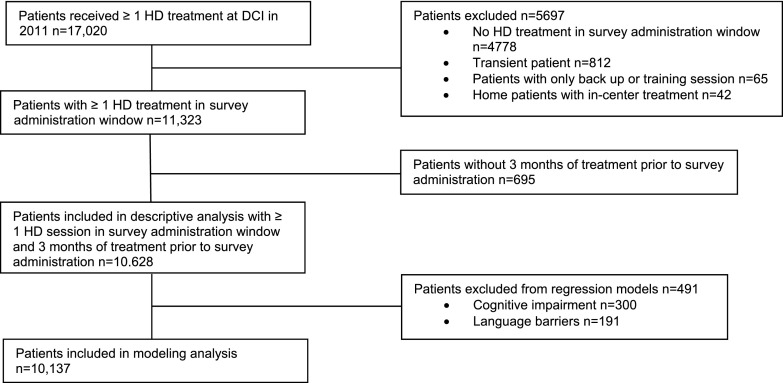

Figure 1 shows patient inclusions and exclusions. The population comprised 10,628 patients treated at 201 DCI clinics; 8213 responders answered at least one survey item (77.3% response rate). More than 99% of respondents answered five or more questions and 96% of respondents answered all survey questions. Of 2415 nonresponders, 250 patients declined; 300 had significant cognitive impairment or severe dementia; and 191 did not read or speak English, Spanish, Chinese, or Vietnamese. No reason was recorded for the remaining 1674 nonresponders.

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion. DCI, Dialysis Clinic, Inc.; HD, hemodialysis.

Table 1 shows demographic data for patients satisfying inclusion criteria. Of the black participants, more were classified as responders than were nonresponders. Of patients designated as other race, more were classified as nonresponders than responders. Patients who had diabetes, who had ESRD for >2.5 years, and whose SF-36 Health Survey PCS scores were below the median were less likely to respond.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of survey responders and nonresponders

| Characteristic | All (n=10,628) (%) | Responders (n=8213) (%) | Nonresponders (n=2415) (%) | P Value: Responders versus Nonresponders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age ≥ 63 yr | 48.8 (47.9–49.8) | 48.5 (47.5–49.6) | 49.7 (47.7–51.8) | 0.3 |

| Men | 55.0 (54.1–56.0) | 55.0 (53.9–56.0) | 55.1 (53.1–57.1) | 0.9 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 45.4 (44.4–46.3) | 46.3 (45.3–47.4) | 42.0 (40.1–44.0) | <0.001 |

| White | 47.3 (46.4–48.3) | 47.1 (46.0–48.2) | 48.0 (46.0–50.0) | 0.5 |

| Other | 7.3 (6.8–7.8) | 6.5 (6.0–7.1) | 10.0 (8.8–11.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetic patients | 58.7 (57.7–59.6) | 58.1 (57.0–59.2) | 60.7 (58.7–62.6) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 2.5 yr at DCI | 56.7 (55.7–57.6) | 56.3 (55.3–57.4) | 57.8 (55.8–59.7) | 0.2 |

| ≥ 2.5 yr with ESRD | 60.3 (59.4–61.2) | 59.6 (58.5–60.7) | 62.6 (60.6–64.5) | <0.01 |

| SF-36 PCS score greater than median | 49.9 (48.9–50.9) | 50.9 (49.8–52.0) | 45.8 (43.5–48.0) | <0.001 |

| SF-36 MCS score greater than median | 50.7 (49.7–51.7) | 50.9 (49.8–52.0) | 49.8 (47.5–52.1) | 0.4 |

Values are percentages (95% confidence intervals). DCI, Dialysis Clinic, Inc.; SF-36, Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey; PCS, Physical Component Summary Scale; MCS, Mental Component Summary Scale.

More responders survived 3 (97.2% [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 96.8% to 97.6%]) and 6 months (93.9% [95% CI, 93.3% to 94.4%]) than nonresponders, of whom 91.9% (95% CI, 90.6% to 93.0%) survived 3 and 86.6% (95% CI, 85.0% to 88.1%) 6 months.

To identify potential biases, a sensitivity analysis added the 695 patients not treated at DCI for at least 3 months. With the exception of the length of time at DCI and duration of ESRD, including these patients did not change any other results.

Response Rates

Clinical Characteristics.

Table 2 shows clinical characteristics over 3 months before survey administration. Compared with responders, nonresponders were more likely to have at least five shortened treatments, more than one missed treatment, and had more days of hospitalization. More nonresponders also had serum albumin concentrations <3.5 mg/dl, and fewer achieved target hemoglobin concentrations and dialysis dose. Serum phosphorous concentrations did not differ between groups.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics in 3 months before survey administration: survey responders and nonresponders

| Characteristic | All (n=10,628) (%) | Responders (n=8213) (%) | Nonresponders (n=2415) (%) | P Value: Overall Responders versus Nonresponders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of treatments shortened | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 27.0 (26.2 to 27.9) | 27.9 (26.9 to 28.8) | 24.1 (22.4 to 5.8) | <0.001 |

| 2–4 | 32.8 (31.9 to 33.7) | 33.4 (32.4 to 34.4) | 30.5 (28.7 to 32.4) | <0.01 |

| ≥5 | 40.2 (39.3 to 41.2) | 38.7 (37.7 to 39.8) | 45.4 (43.4 to 47.4) | <0.001 |

| Missed >1 treatment | 17.8 (17.0 to 18.5) | 17.2 (16.4 to 18.0) | 19.7 (18.1 to 21.3) | <0.01 |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| No hospitalization | 72.7 (71.9 to 73.6) | 75.7 (74.8 to 76.6) | 62.7 (60.8 to 64.7) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 hospitalized days | 10.3 (9.7 to 10.9) | 9.9 (9.2 to 10.5) | 11.7 (10.4 to 13.0) | <0.01 |

| ≥4 hospitalized days | 17.0 (16.2 to 17.7) | 14.4 (13.7 to 15.2) | 25.5 (23.8 to 27.3) | <0.001 |

| Albumin | ||||

| <3.5 g/dl | 18.0 (17.3 to 18.8) | 15.7 (14.9 to 16.5) | 25.9 (24.1 to 27.6) | <0.001 |

| 3.5–3.9 g/dl | 48.3 (47.4 to 49.3) | 49.0 (47.9 to 50.1) | 46.1 (44.1 to 48.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥4 g/dl | 33.6 (32.7 to 34.5) | 35.3 (34.2 to 36.3) | 28.1 (26.3 to 29.9) | <0.001 |

| Kt/Vsp goal | 87.9 (87.3 to 88.5) | 88.4 (87.7 to 89.1) | 86.2 (84.8 to 87.5) | 0.003 |

| Hemoglobin ≥10 g/dl | 91.3 (90.8 to 91.9) | 92.0 (91.4 to 92.5) | 89.3 (88.1 to 90.5) | <0.001 |

| PO4 >5.5 mg/dl | 46.8 (45.8 to 47.7) | 46.8 (45.8 to 47.9) | 46.7 (44.7 to 48.7) | 0.8 |

Values are percentages (95% confidence intervals) and P value from chi-square test.

Table 3 summarizes logistic regression models assessing the outcome of nonresponse to the survey, including patients who completed the survey and the subset of nonresponders who declined or did not have a documented explanation. Univariate logistic regression analyses found nonresponders more likely to be young and white or of other race. Nonresponders were also more likely to have missed a treatment, to have shortened five or more treatments, and to have spent more days in the hospital. Nonresponders were more likely to have lower albumin and hemoglobin and higher phosphorous concentrations and lower dialysis dose. In adjusted multivariate logistic and random intercept models, race, missing and shortening treatments more frequently, more days in the hospital, and lower serum albumin concentrations independently predicted survey nonresponse.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression models and random intercept model of nonresponse

| Effect | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression | Random Intercept Logistic Regression | |

| Age (<63 versus ≥63 yr) | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.20) | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.26) |

| Sex (female versus male) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.04) | 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.04) |

| Race | |||

| Referent: black | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| White | 1.16 (1.04 to 1.29) | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.34) |

| Other | 1.29 (1.06 to 1.57) | 1.41 (1.12 to 1.73) | 1.57 (1.21 to 2.00) |

| Diabetes (diabetic versus nondiabetic) | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.17) | ||

| Time at DCI (>2.5 versus ≤2.5 yr) | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) | ||

| Time with ESRD (>2.5 versus ≤2.5 yr) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.21) | ||

| Missing >1 treatment in prior 3 mo | 1.34 (1.18 to 1.51) | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.31) | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.43) |

| Shortened treatment in prior 3 mo | |||

| Referent: 0 or 1 treatment | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2–4 treatments | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.24) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.24) |

| ≥5 treatments | 1.47 (1.29 to 1.66) | 1.39 (1.21 to 1.59) | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.55) |

| Hospitalized days in prior 3 mo | |||

| Referent: none | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1–3 total | 1.38 (1.17 to 1.62) | 1.28 (1.08 to 1.51) | 1.27 (1.06 to 1.52) |

| >3 total | 2.17 (1.93 to 2.45) | 1.88 (1.65 to 2.14) | 1.81 (1.56 to 2.09) |

| 3-mo mean albumin in prior 3 mo | |||

| Referent: ≥4.0 g/dl | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 3.5–3.9 g/dl | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.27) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.22) | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.26) |

| <3.5 g/dl | 1.85 (1.61 to 2.12) | 1.47 (1.26 to 1.71) | 1. 59 (1.35 to 1.88) |

| 3-mo mean phosphorous (>5.5 versus ≤5.5 mg/dl) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23) | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.19) | 1.11 (0.99 to 1.25) |

| 3-mo mean hemoglobin (<10 versus ≥10 g/dl) | 1.48 (1.26 to 1.74) | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.28) | 1.08 (0.89 to 1.30) |

| Kt/V (below versus at or above goal) | 1.38 (1.2 to 1.59) | 1.15 (0.99 to 1.33) | 1.17 (0.99 to 1.39) |

| SF-36 scorea | |||

| Baseline PCS score (below median versus above median) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.35) | –a | –a |

| Baseline MCS score (below median versus above median) | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.19) | –a | –a |

DCI, Dialysis Clinic, Inc.; SF-36, Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey; PCS, Physical Component Summary Scale; MCS, Mental Component Summary Scale.

SF-36 scores missing for 7.2% and 18.2% of patients who took the survey and did not take the survey, respectively, so the composite scores are not included in the multivariate models

Facility Characteristics and Survey Administration Window.

At the patient level, the mean survey window time was 19.9 days (range, 1–231 days). At the clinic level, there was a small but significant inverse association between survey window length and response rate (r=−0.18; P=0.01). Response rates were highest in clinics that had the shortest administration windows (80.2% for a <2-week window, 75.5% for a 2- to 4-week window, 71.6% for a >4 week window); >75% of clinics had a survey window of ≤4 weeks. Survey administration window length was also positively associated with average census (r=0.36; P<0.001). Clinic census was not associated with response rate (r=−0.07; P=0.32).

Corollaries of Overall Patient Satisfaction with Care

We hypothesized that overall satisfaction with care, measured by one of the nine survey items, might correlate with patient demographic or clinical characteristics. Table 4 shows the corollaries of overall satisfaction with care. None of the following significantly correlated with overall satisfaction: patient sex; presence or absence of diabetes; number of days of hospitalization in the last year; duration of treatment at DCI; and hemoglobin, serum albumin, or phosphorus concentrations. Patient age, race, vintage, and a history of missed or shortened treatments did independently correlate with overall satisfaction.

Table 4.

Corollaries of overall patient satisfaction with care

| Effect | Least-Squares Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median age | ||

| <63 yr | 1.91 (1.86 to 1.97) | <0.001 |

| ≥63 yr | 1.84 (1.78 to 1.90) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.76 (1.71 to 1.81) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.93 (1.83 to 2.03) | |

| Black | 1.93 (1.88 to 1.99) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.88 (1.82 to 1.94) | 0.58 |

| Male | 1.87 (1.82 to 1.93) | |

| Time since ESRD | ||

| ≤2.5 years | 1.79 (1.73 to 1.84) | <0.001 |

| >2.5 years | 1.96 (1.91 to 2.02) | |

| Missed and not rescheduled treatmentsa | ||

| >1 | 1.92 (1.85 to 1.98) | 0.002 |

| 0 or 1 | 1.83 (1.78 to 1.88) | |

| No. of shortened treatmentsa | ||

| ≥5 | 1.92 (1.87 to 1.98) | 0.004 |

| 2–4 | 1.87 (1.81 to 1.93) | |

| 0–1 | 1.84 (1.77 to 1.90) | |

| Albuminb | ||

| <3.5 g/dl | 1.84 (1.77 to 1.90) | 0.07 |

| 3.5–3.9 g/dl | 1.90 (1.85 to 1.96) | |

| ≥4.0 g/dl | 1.89 (1.83 to 1.95) | |

| Kt/Vb | ||

| At goal | 1.85 (1.80 to 1.89) | 0.05 |

| Below goal | 1.91 (1.84 to 1.98) |

Survey question: “Overall ... the quality of care and services you get from this clinic.” Response options are as follows, with scores in parentheses: Excellent (1), Very good (2), Good (3), Fair (4), and Poor (5). Lower values correspond to higher satisfaction.

Missed and shortened treatments are all based on all treatments in the 3 months before patient completed the satisfaction survey.

Clinical data are 3-month averages before patient completed the satisfaction survey.

Discussion

The differences between patients who respond to a survey and those who do not respond highlight the characteristics of patients who are not contributing to the results. Understanding these characteristics may allow providers to appreciate the limitations of the instrument, the survey process, or the results themselves. Response itself is an outcome and comparing responders and nonresponders can help to identify potential reasons for low response rates and areas for improvement. Finally, whether a patient responds may be an important variable in risk stratification.

The 77.3% response rate compares favorably with reported completion rates for kidney disease patient surveys (3). For many nonresponders (69.0%), staff had not specified the reason for nonresponse. Responders were healthier and more adherent, at least to the dialysis schedule. They were more likely to be black, to have fewer hospitalizations and days in the hospital, to have higher PCS scores, and to have higher albumin and hemoglobin concentrations. Nonresponders proved more likely to die within 3 months and 6 months of survey administration.

It seems likely that healthier patients are more willing to complete surveys and that staff hesitate to ask sicker patients to do so. Healthier patients, who are spending more time in the facility, are certainly more available to survey. However, these results do not tell us whether sicker patients would rate facilities differently or whether, if refusal to respond were recorded completely, they would more often decline to complete a survey. Patients who shorten treatments or miss treatments that are not rescheduled are more likely to be nonresponders. These patients may very well be less satisfied, and missing treatments may indicate their dissatisfaction. Subsequently, satisfaction survey results in hemodialysis patients may be subject to a positive bias.

It seems paradoxical that the duration of the window for survey administration and response rate should be inversely related. Presumably, longer survey windows reflect an attempt to increase response rates. A longer survey administration window might be a marker for a lackadaisical approach to survey administration. Actively encouraging response during a brief data collection period may be more productive. More compressed data collection also allows earlier result reporting, when the findings are more relevant to quality improvement efforts.

Data on satisfaction and experience of care in CKD, including patients with ESRD, are limited (3–7). In some studies, patients responded to self-administered surveys, while others were interviewed. Survey populations differ markedly; some were very small. No survey has been reported from more than one population, and many are of questionable reliability and validity.

Among studies of patient satisfaction with dialysis care, two briefly compared the characteristics of responders and nonresponders. The Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for End-stage Renal Disease (CHOICE) study (5) asked the 736 incident patients enrolled to complete a satisfaction survey; 89% responded, showing no statistically significant differences in hemodialysis patient characteristics (age, sex, education, marital status, work employment, distance from dialysis center, days receiving dialysis, and PCS or MCS or comorbidity scores) between responders and nonresponders. As was seen in CHOICE, we found no differences by age or sex. We did find statistically significant differences in race, missing or shortening of dialysis treatments, number of hospital days, serum albumin concentrations, and survival between responders and nonresponders. In contrast to the CHOICE investigators, we found that nonresponders were more likely to have PCS scores below the median. Both CHOICE and this analysis studied patients from DCI. The CHOICE study’s limitation to patients initiating dialysis within the past 3 months and its inclusion of both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients may have contributed to the differences.

Among 333 patients with CKD not treated by dialysis, Harris et al. found older patients less likely to respond (74.4 versus 69.1 years; P<0.001) but no differences by sex, race, serum creatinine concentrations, or presence of diabetes (3). The difference in patient populations and severity of kidney disease make it difficult to compare these findings to ours. Three studies assessing ESRD patient experience of care did not compare the characteristics of responders and nonresponders (8–10).

We found older patients who were white, newer to hemodialysis, and more adherent to the hemodialysis schedule to be more satisfied with care. A previous study found older, black, low-income patients who underwent hemodialysis and had comorbidities rated the quality of care lower than did other patients (6). We are unaware of previous reports of association of vintage or of adherence to the hemodialysis schedule with satisfaction.

The current study has several limitations. The lack of anonymity may have reduced the response rate and may also have led to self-selection, biasing the results. If less satisfied patients in some way felt more vulnerable than other patients, they might have been less likely to respond. However, for almost 20 years, the survey has been an effective tool for evaluating clinic performance and has demonstrated changes before and after implementation of quality improvement initiatives at individual facilities (data not shown). These data, collected within the constraints of routine clinical care, are incomplete. Although clinics are advised to limit the survey administration window, there is no stringent timeline. As a result, the survey administration window varies across clinics. Structural characteristics of the organization may limit generalizability: DCI is a moderate-sized, not-for-profit dialysis organization.

Our results have implications for analysis of the ICH-CAHPS survey results. The ICH CAHPS data collection process mandated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (11) does not define a structured and consistent process for recording explanations for nonresponse. We found that demographic and clinical characteristics correlated with the probability that an individual patient will complete a satisfaction survey. Some of the clinical information is not available in CrownWeb. These characteristics should be taken into account in evaluating survey response rates. The finding that shortening and missing treatments correlates with the likelihood of response suggests that traditional case-mix adjustment may not be sufficient.

Sicker patients were underrepresented in DCI satisfaction survey results. This will also be true of a survey of experience of care, such as ICH CAHPS, because healthier patients are more available for survey. As a result, changes or improvements made on the basis of patient reports may not be responsive to the needs and preferences of the most vulnerable patients. The association between nonadherence to dialysis treatment and survey nonresponse may be even more meaningful. It seems likely that patients who do not adhere to treatment schedules are less satisfied and have worse experience of care than patients who show up for treatment. It is therefore quite possible that the very patients who could give the most important information will be underrepresented. Quality improvement efforts should focus on raising the overall response rate, in the hope that overall improvement will increase the response rate in these underrepresented groups, enhancing the quality of the information and reducing bias. For all of these reasons, results from the ICH CAHPS survey should be appropriately statistically adjusted before they are used to compare, rank, or influence payment to facilities.

These results have implications both for assessment of dialysis patient satisfaction or experience of care and for the use of such data to compare facilities’ performance and/or to determine payment. Individual facilities and the survey organizations collecting ICH CAHPS data should focus on increasing response rates and enhancing participation from underrepresented groups.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dialysis Clinic, Inc. staff and patients who administer and complete these very important surveys.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Press I: The basics of patient satisfaction. In: Patient satisfaction: understanding and managing the experience of care, 2nd Ed., Chicago, IL, Health Administration Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson EC, Larson CO, Davies AR, Gustafson D, Ferreira PL, Ware JE, Jr: The patient comment card: A system to gather customer feedback. QRB Qual Rev Bull 17: 278–286, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, Tierney WM: Correlates of health care satisfaction in inner-city patients with hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency. Soc Sci Med 41: 1639–1645, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovac JA, Patel SS, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL: Patient satisfaction with care and behavioral compliance in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 1236–1244, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin HR, Fink NE, Plantinga LC, Sadler JH, Kliger AS, Powe NR: Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA 291: 697–703, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Dialysis patient ratings of the quality of medical care. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 284–289, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirchgessner J, Perera-Chang M, Klinkner G, Soley I, Marcelli D, Arkossy O, Stopper A, Kimmel PL: Satisfaction with care in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 70: 1325–1331, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paddison CAM, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Farley DO, Lyratzopoulos G, Hambarsoomian K, Dembosky JW, Roland MO: Experiences of care among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD: Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 440–449, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidmer BA, Cleary PD, Keller S, Evensen C, Hurtado MP, Kosiak B, Gallagher PM, Levine R, Hays RD: Development and evaluation of the CAHPS (Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey for in-center hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 753–760, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood R, Paoli CJ, Hays RD, Taylor-Stokes G, Piercy J, Gitlin M: Evaluation of the consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems in-center hemodialysis survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1099–1108, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ICH CAHPS Survey Administration and Specifications Manual Version 3, 2015. Available at: https://ichcahps.org/Portals/0/ICH_SurveyAdminManual.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2015