Abstract

Objectives:

Uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections (uSSSIs) are a common clinical problem. Majority are caused by staphylococci and streptococci. Different oral antibiotics are used for uSSSI, with comparable efficacy but varying treatment duration, cost, and adverse event profile. Azithromycin is used in uSSSI in adults conventionally in a dose of 500 mg once for 5 days. The extensive tissue distribution of the drug and its long elimination half-life prompted us to explore whether a single 2 g dose of the drug would produce a response in uSSSI comparable to conventional dosing.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a parallel group, open-label, randomized, controlled trial (CTRI/2015/07/005969) with subjects of either sex, ≥12 years of age, presenting with uSSSI to the dermatology outpatient department. One group (n = 146) received 2 g single supervised dose while the other (n = 146) received conventional dose of 500 mg once daily for 5 days. Subjects were followed up on day 4 and day 8. Complete clinical cure implied complete healing of lesions, without residual signs or symptoms, within 7 days.

Results:

High cure rate was observed in both arms (97.97% and 98.63%, respectively) along with noticeable improvement in symptom profile from baseline but without statistically significant difference between groups. However, excellent adherence (defined as no tablets missed) was better in single dosing arm (98.65% vs. 86.30%). Tolerability was also comparable between groups with the majority of adverse events encountered being gastrointestinal in nature and mild.

Conclusions:

Single 2 g azithromycin dose achieved the same result as conventional azithromycin dosing in uSSSI with comparable tolerability but with the advantage of assured adherence. This dose can, therefore, be recommended as an alternative and administration supervised if feasible.

KEY WORDS: Azithromycin, dermatology, randomized controlled trial, uncomplicated skin and skin structure infection

Introduction

The skin surface represents a protective boundary between the body and the outside world. It is composed of elastic tissue, collagen fibers, vascular channels, nerve fibers, and several cell types including squamous epithelial cells (keratinocytes), melanocytes, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, neural end organs, and axonal processes, and adnexal components such as sweat glands and hair follicles. Apart from maintaining structural integrity these cells play an important part in various cutaneous inflammatory and infectious conditions by liberating various cytokines.[1]

Skin infections have been categorized into two broad types:[2,3](1) Uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections (uSSSI) such as simple abscesses, impetigo, furunculosis, folliculitis, ecthyma, and erysipelas,[4,5,6] and (2) complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI)[3] like infection either in deeper soft tissues or requiring significant surgical intervention, such as infected ulcer, burns, and major abscesses or a significant underlying disease state that complicates the management. Superficial infections or abscesses at sites, like the rectal area, where the risk of anaerobic or Gram-negative pathogen involvement is high, are also considered as complicated infections.

A skin and skin structure infection is usually bacterial in origin and often requires treatment by antibacterial drugs. A combination of culture, biopsy, serologic studies,[7] and detection of antibodies from immunofluorescence techniques[6] suggest that Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common etiologic agents. Occasionally, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Group G or C streptococci, and in neonates, Group B streptococci or, uncommonly, Escherichia coli, are the causal organisms. Rarely, other agents such as Pasteurella multocida, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, and Aeromonas hydrophila are encountered, for instance in cellulitis following cat or dog bites.

Empirical therapy for uSSSI is directed by the history of the illness, location, and character of the lesions, and age and immune status of the patient. If fever, lymphadenopathy, and other constitutional signs, that is, features suggestive of complicated cSSSI, are absent, treatment may be initiated orally on ambulatory basis.[8] Antibiotics used to treat these infections are usually given for a period of 5–10 days.[9,10] Many of them are given multiple times per day such as mupirocin ointment 2% applied thrice daily, cefalexin 500 mg orally 3 or 4 times daily, co-amoxiclav 625 mg orally thrice daily, erythromycin 500 mg orally 4 times daily, clindamycin 300 mg orally 4 times daily or 600 mg intravenously (IV) thrice daily, cefazolin 1 g IV thrice daily, and so on.

Evidently, multiple daily dosing is likely to lead to adherence problems. Therefore, any drug with similar spectrum but less frequency or duration of use would be a more preferred antibiotic. Azithromycin fits this requirement and is a very commonly used drug for uSSSI.[11] Following oral administration, the drug quickly gets sequestrated in the intracellular compartment and this results in high tissue concentration. Subsequent slow release from tissue reservoir makes the terminal phase half-life as long as 11–14 h. An even longer half-life of 68 h is achieved when multiple doses are consumed. This pharmacokinetic behavior[12] provides the basis for single supervised dose or single daily dose for 5 days dosing schedule in most infections including urogenital infections, respiratory tract infections, and skin and skin structure infections. Improved adherence is likely in ambulatory patients in comparison to other antimicrobials that need to be given more frequently or for longer duration.

Unlike sexually transmitted infections,[13] the use of single dose azithromycin, which offers the opportunity for zero nonadherence, is not in vogue for skin and skin structure infections. We therefore decided to compare single supervised dose of 2 g azithromycin with conventional 500 mg once daily for 5 days dosing in uSSSI. The latter regimen is already well-established through clinical trials.[7,9]

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective, parallel group, open-label, randomized, controlled clinical trial conforming to Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines for ethical clinical research[14] and the Schedule Y Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the Government of India.[15] Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained beforehand.

The study setting was the outpatient dermatology clinic in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Over a period of 15 months, subjects of either sex aged at least 12 years, with clinically defined cases of uSSSI were enrolled if they provided written informed consent. Consent was obtained from the accompanying parent for subjects below 18 years of age and children and teenagers between 12 years and 18 years of age also provided informed assent. Pregnancy or breast-feeding, history of hospitalization or systemic antimicrobial use within past 14 days, signs and symptoms suggestive of cSSSI, history of immunosuppression, and recent use of certain medications (e.g. warfarin, phenytoin, methotrexate, and other immunosuppressive drugs, systemically administered antibacterial agents) were exclusion factors. Subjects with history of disorders of any vital organ, alcohol or substance abuse, allergy to macrolides antibacterials, and without access to telephone were also excluded.

Sampling was purposive and occurred once a week in the concerned outpatient department (OPD). Maximum three subjects were recruited in a day in order of their appearance. Eligible subjects were randomized in fixed blocks of 30 using computer generated random number lists to either Group A (azithromycin single dose regimen arm) or Group B (azithromycin conventional dose regimen arm) in 1:1 ratio. There was no stratification. The test group received azithromycin 2 g in tablet form – four 500 mg tablets were taken orally under the supervision of the investigator with 200 mL of water. The control group received the first tablet of 500 mg under supervision and was then asked to use up four more tablets at home at 24 h intervals, keeping atleast 1 h gap before taking any food. AZIBACT-500 SI tablets marketed by M/s Ipca Laboratories, Mumbai, were used in both arms. The medication was purchased (same batch) from a local distributor.

The concerned skin conditions, that is, the uSSSI, were diagnosed in presence of a dermatologist. Each patient was followed up after 3 days and then after 7 days of taking the single dose or first dose of the study drug as applicable. General clinical and dermatological examination and recording of vital signs were done at each visit. Adverse events were recorded as complained of by patients or as observed by the clinician. No laboratory investigations were specifically ordered.

The primary outcome measure was clinical response characterized by cessation of the spread of redness, edema, and induration around the lesion or reduction of the size of the lesion at 72 h. Absence of such resolution at 72 h was considered as absence of clinical response. Secondary outcome measures were:(a) Clinical cure at 7 days, characterized by complete resolution of all signs of inflammation and obvious resolution of the lesion itself on the 8th day after taking the single dose or first dose of study drug. Absence of such response, increase in the size of the lesion or associated inflammation or the use of any rescue antibiotic (or any other rescue measure like abscess drainage) were considered as clinical failure. (b) Suspected adverse drug reactions in the form of altered vital signs or treatment emergent adverse events.

Adherence was rated on the basis of number of tablets consumed. It was rated excellent if all doses were taken within ± 2 h of the scheduled time; good if only one dose was missed or delayed by >2 h, and poor if more than one was missed or delayed.

The sample size for the study was determined conventionally and not considering a noninferiority design. It was estimated that 127 subjects would be required per group in order to detect a 10% difference in primary outcome measure between the groups with 80% power and 5% probability of Type I error. This calculation assumed 1:1 randomization and that the response rate would be 86% in the comparator group[16] and higher in the test drug group. Assuming a 15% dropout rate, the recruitment target was set at 149 subjects per group or 298 subjects overall (rounded off to 300 subjects). nMaster 2.0 (Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College, Vellore; 2012) software was used for sample size calculation.

Data have been summarized by routine descriptive statistics. Numerical variables were compared between groups by Student's t-test, if normally distributed, or by Mann–Whitney U-test, if otherwise. Fisher's exact test or Pearson's Chi-square test was employed for intergroup comparison of categorical variables. Individual sign-symptoms were coded as categorical variables and were assessed for change in frequency over time by Cochran's Q test. All analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance implied P < 0.05. Statistica version 6 (Tulsa, Oklahoma: StatSoft Inc., 2001) and GraphPad Prism version 5 (San Diego, California: GraphPad Software Inc., 2007) software were used for statistical analysis.

Results

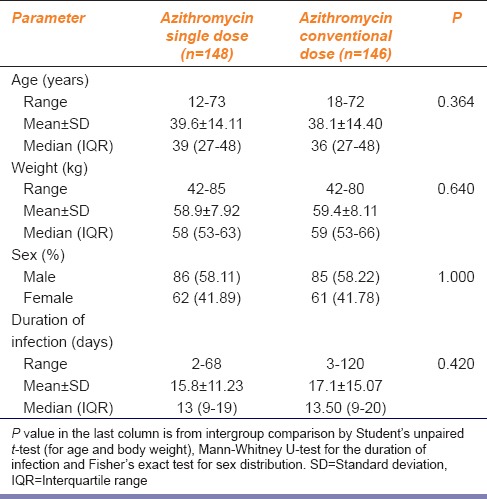

During the recruitment period of the study, 525 cases of uSSSI were screened of whom 202 did not fulfill the eligibility criteria and 23 refused to participate. The remaining 300 cases were allocated to the two study groups in equal numbers. Data of 148 subjects in arm A and 146 subjects in arm B were analyzed. The analysis was on modified intention-to-treat basis in the sense that all subjects who returned for at least one postbaseline visit (day 3 visit in this case) were included in the analysis. Age, weight, sex distribution, and duration of the infection were comparable between the two arms as summarized in Table 1. Vital sign parameters were also comparable at baseline and remained so at follow-up and end-of-study visits (data not shown).

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline parameters in the study groups

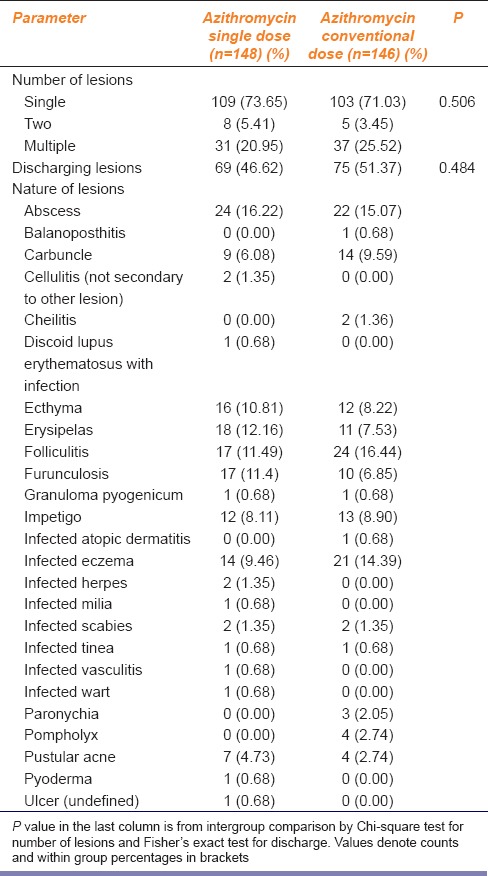

Baseline characteristics of the lesions in terms of their number and nature are summarized in Table 2 and were also comparable between the two arms.

Table 2.

Number and nature of lesions in the two study groups

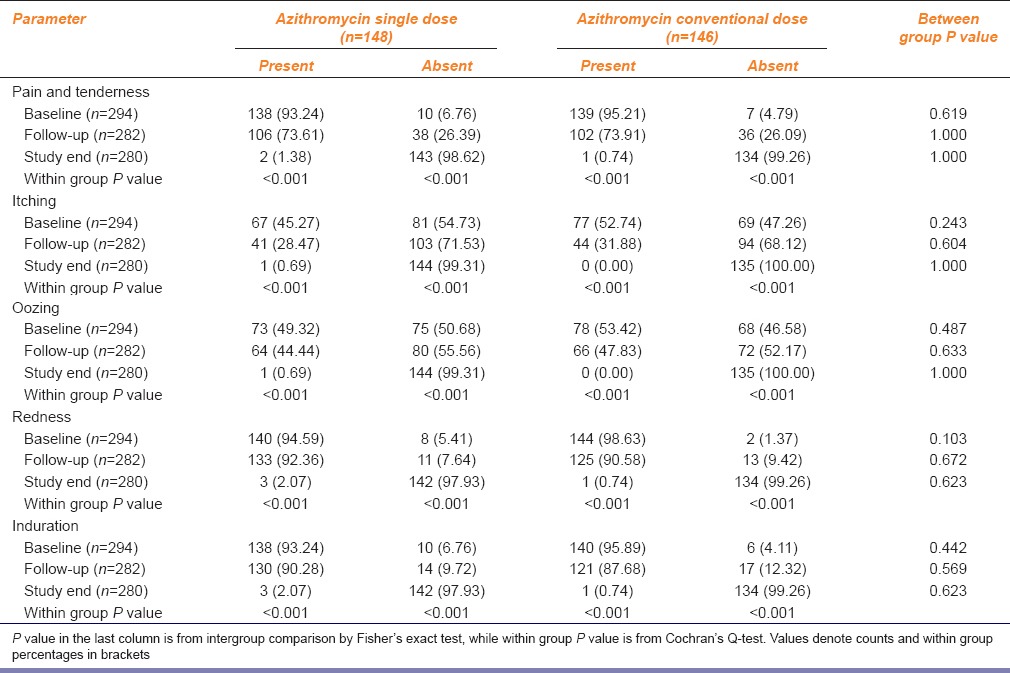

Table 3 summarizes the change in lesion characteristics with treatment. The resolution of individual signs and symptoms was highly significant over 7 days in both groups and remained comparable between the two dosing groups throughout. At the end of study, cure was recorded in 145 subjects (97.97%) who received single dose azithromycin versus 144 (98.63%) subjects who received conventional 5 days azithromycin; the difference is statistically not significant.

Table 3.

Resolution of individual sign-symptoms in the two study groups

Both dosing regimens were well-tolerated overall. In both groups 10 adverse events were reported. With the exception of spontaneously settling maculopapular rash in one subject receiving single 2 g dose of azithromycin, all other events were gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort or loose stools) and mild. No specific treatment or drug withdrawal was required in any instance and there were no hospitalizations during the study. The differences in frequency of individual adverse events between the two groups were not statistically significant.

Drug administration in the single dose arm was fully supervised so that there is no issue of lack of adherence in this arm except for two subjects who were able to take 3 rather than 4 tablets. In the other arm, excellent, good, and poor adherence was recorded in 126 (86.30%), 7 (4.79%), and 13 (8.90%) subjects, respectively. The difference in treatment adherence was highly significant (P < 0.001) in favor of the single dose arm.

Discussion

This is possibly the first randomized controlled study from India to compare the effectiveness of single supervised dose of azithromycin with standard azithromycin dosing in uSSSI. Being a derivative from erythromycin, azithromycin is active against Gram-positive organisms like staphylococci, and streptococci. In addition, it shows extended spectrum activity against Gram-negative organisms such as Haemophilus influenzae, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Borrelia burgdorferi. Biliary elimination, long terminal elimination half-life, and less of inhibition of hepatic microsomal enzymes are other advantages in comparison to older macrolides like erythromycin and clarithromycin.[11,12,17] Single dose administration of the drug, particularly if supervised in the OPD setting, would solve the problem of reduced adherence.

In this study, only 3 (2.03%) subjects in Group A and 2 (1.37%) in Group B did not respond to the treatment. These response rates conform to cure rate with azithromycin therapy in uSSSI reported in previous studies.[18]

This study was conducted mainly to show the efficacy of single dose regimen but at the same time adverse events comprised a secondary end point. As far as known safety issues are concerned, majority of adverse effects of azithromycin are gastrointestinal like nausea, vomiting, and loose stool.[12] A similar profile was obtained in our study. A single instance of mild maculopapular skin rash was encountered in one subject taking single dose azithromycin. This subsided spontaneously the same day and required no specific treatment.

The results suggest that the effectiveness and tolerability of single 2 g azithromycin dose were comparable to that of standard azithromycin dosing in the management of uSSSI. However, significantly less adherence was noted in the conventional dosing arm compared to single supervised dosing.

As stated earlier, apart from azithromycin, uSSSIs can also be successfully treated with several other antimicrobial agents. Depending on the drug, clinical efficacy rates with these agents for uSSSIs range from approximately 78% to 100%.[19,20] However, the dosing regimens of most other antimicrobial agents would be less convenient than single dose azithromycin. Several must be given either 3–4 times daily or for a period of 7–10 days. With single dose azithromycin, there would be minimum risk of nonadherence, and therefore reduced risk of treatment failure and emergence of drug resistance.

The study has its share of limitations. Children <12 years of age were not included for ethical reasons. The open label design introduces possibility of bias in evaluating signs and symptoms but, considering the nature of the dosing, a blinded design was difficult to implement in practice and was therefore not attempted. The bacterial nature of the infections was not confirmed beforehand through microbiological testing. However, the diagnosis was verified by an experienced dermatologist before randomization and in the OPD setting, antimicrobial treatment of uSSSI is usually provided on an empirical basis. We replicated this model and the results make it obvious that empirical therapy works in most situations for uSSSI. Finally, we had no scope for assessing possible relapse of the infections.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we can conclude that in uSSSI in older children and adults, single 2 g dose of azithromycin, given under supervision, is generally well-tolerated and can achieve clinical cure rates comparable to conventional azithromycin dosing within 7 days.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Anusree Gangopadhyay and Dr. Sanchita Bala, Residents in the Department of Dermatology, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, for assistance with patient evaluation.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: Mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:211–22. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seupaul RA. Cephalexin is as effective as clindamycin for the treatment of uncomplicated soft tissue and skin infections in children. J Pediatr. 2011;158:861–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dryden MS. Complicated skin and soft tissue infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(Suppl 3):iii35–44. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atanaskova N, Tomecki KJ. Innovative management of recurrent furunculosis. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan W, Li W, Mu C, Wang L. Ecthyma gangrenosum and multiple nodules: Cutaneous manifestations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in a previously healthy infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:204–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard P, Bedane C, Mounier M, Denis F, Catanzano G, Bonnetblanc JM. Streptococcal cause of erysipelas and cellulitis in adults. A microbiologic study using a direct immunofluorescence technique. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:779–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson B, Jorup-Rönström C, Karkkonen K, Sjöblom AC, Holm SE. Erysipelas: Clinical and bacteriologic spectrum and serological aspects. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1091–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorup-Rönström C, Britton S, Gavlevik A, Gunnarsson K, Redman AC. The course, costs and complications of oral versus intravenous penicillin therapy of erysipelas. Infection. 1984;12:390–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01645222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, Ellis MW, Starnes WF, Hasewinkle WC. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1669–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergkvist PI, Sjöbeck K. Antibiotic and prednisolone therapy of erysipelas: A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:377–82. doi: 10.3109/00365549709011834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters DH, Friedel HA, McTavish D. Azithromycin. A review of its antimicrobial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs. 1992;44:750–99. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199244050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New York: Pfizer Inc; 2013. Anonymous. ZITHROMAX® package insert. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chico RM, Hack BB, Newport MJ, Ngulube E, Chandramohan D. On the pathway to better birth outcomes? A systematic review of azithromycin and curable sexually transmitted infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:1303–32. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.851601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2006. Indian Council of Medical Research. Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schedule Y, editor. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India; 2005. The Drugs and Cosmetics Act and Rules (as amended up to 30th June, 2005) pp. 503–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lassus A. Comparative studies of azithromycin in skin and soft-tissue infections and sexually transmitted infections by Neisseria and Chlamydia species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25(Suppl A):115–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piscitelli SC, Danziger LH, Rodvold KA. Clarithromycin and azithromycin: New macrolide antibiotics. Clin Pharm. 1992;11:137–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson SE. The management of skin and skin structure infections in children, adolescents and adults: A review of empiric antimicrobial therapy. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52:414–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolen T. Comparative studies of cefprozil in the management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:866–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02111354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schatz BS, Karavokiros KT, Taeubel MA, Itokazu GS. Comparison of cefprozil, cefpodoxime proxetil, loracarbef, cefixime, and ceftibuten. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30:258–68. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]